Abstract

Background

Universal antiretroviral therapy (ART) for all pregnant/ breastfeeding women living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), known as Prevention of mother-to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) Option B+ (PMTCTB+), is being scaled up in most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. In the transition to PMTCTB+, many countries face challenges with proper implementation of the HIV care cascade. We aimed to describe the feasibility of a PMTCTB+ approach in the public health sector in Swaziland.

Methods

Lifelong ART was offered to a cohort of HIV+ pregnant women aged ≥16 years at the first antenatal care (ANC1) visit in 9 public sector facilities, between 01/2013 and 06/2014. The study enrolment period was divided into 3 phases (early: 01–06/2013, mid: 07–12/2013 and late: 01–06/2014) to account for temporal trends. Kaplan-Meier estimates and Cox proportional-hazards regression models were applied for ART initiation and attrition analyses.

Results

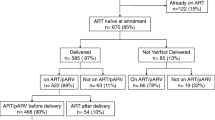

Of 665 HIV+ pregnant women, 496 (74.6%) initiated ART. ART initiation increased in later study enrolment phases (mid: aHR: 1.41; later: aHR: 2.36), and decreased at CD4 ≥ 500 (aHR: 0.69). 52.9% were retained in care at 24 months. Attrition was associated with ANC1 in the third trimester (aHR: 2.37), attending a secondary care facility (aHR: 1.98) and ART initiation during later enrolment phases (mid aHR: 1.48; late aHR: 1.67). Of 373 women eligible, 67.3% received a first VL. 223/251 (88.8%) were virologically suppressed (< 1000 copies/mL). Of 670 infants, 53.6% received an EID test, 320/359 had a test result recorded and of whom 7 (2.2%) were HIV+.

Conclusions

PMTCTB+ was found to be feasible in this setting, with high rates of maternal viral suppression and low transmission to the infant. High treatment attrition, poor follow-up of mother-baby pairs and under-utilisation of VL and EID testing are important programmatic challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The use of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) for prevention of HIV transmission is widely accepted as a ‘Treatment as Prevention’ strategy. Mono-therapy with Zidovudine (AZT) and combined antiretroviral therapy (ART) are effective in reducing vertical HIV transmission from mother to child [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Lifelong ART decreases morbidity and mortality in adults across all CD4 counts [8, 9], protects the foetus from HIV infection from the time of conception in subsequent pregnancies and reduces the risk of transmission to partners [10,11,12]. In 2013, the WHO recommended the use of lifelong ART in all pregnant and breastfeeding women at the time of HIV diagnosis regardless of CD4 count, known then as prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) option B+ (PMTCTB+) [13].

The HIV prevalence in Swaziland is estimated at 31% among adults (18–49 years old) [14], and annual HIV incidence is high at 2.5% [15]. HIV disproportionately affects women and peaks at 49% in the age-group 25-29 years old [15] and is overall 41.1% among pregnant women [15, 16]. Until 2014, the Swaziland National PMTCT Program applied the WHO PMTCTA approach, whereby women with CD4 < 350 and/or WHO Stage 3/4 disease were eligible for lifelong ART. Women not fulfilling these criteria were offered AZT from 14 weeks of gestation, AZT/3TC at delivery for one week, followed by AZT until the end of the breastfeeding period. The infants received Nevirapine syrup immediately after delivery and for the duration of the breastfeeding period or through 6 weeks if they were not breastfed [17, 18]. In 2012 the reported PMTCTA coverage was > 80% and maternal to child transmission estimated at 2.4% at 6 weeks [19].

In 2013, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and the Swaziland Ministry of Health initiated a PMTCTB+ implementation study in the southern Shiselweni region. The objective was to determine feasibility of PMTCTB+ in the public health sector and compile lessons learned to inform national policy and scale-up. Interim results of ART initiation rates during the early study implementation period have been described in detail elsewhere [20]. Here we present the final outcomes of this study from the perspective of the pregnant women (ART initiation and retention in care (RIC) rates, viral load (VL) testing uptake and suppression) as well as of their exposed infants (early infant diagnosis (EID) uptake, and HIV transmission rates).

Methods

Setting

This was a prospective PMTCTB+ implementation cohort study in Nhlangano health zone, southern Swaziland. Predominantly rural, it comprises one secondary and 8 primary care facilities providing HIV diagnosis and ART integrated into maternal and child health care services. Full details of the setting and the study have been described elsewhere [20].

From 28 January 2013 to 30 June 2014 newly diagnosed and previously known HIV+ pregnant women aged ≥16 years were enrolled into the study and offered lifelong ART at the first ante-natal care (ANC) visit. At completion of study enrolment, PMTCTB+ was adopted as the standard of care nationally, and the study follow-up period coincided with the national roll out. Trained HIV testing counsellors (HTCs) performed HIV testing, treatment preparation, and ART follow-up counselling. A serial rapid testing algorithm was applied using the Alere Determine™ HIV-1/2 rapid test followed by the Uni-Gold™ test on whole blood. Trained nurses initiated ART and performed follow-up visits and ART refills, while mobile medical doctors attended clinically complicated HIV patients. Because PMTCTA remained the standard of care nationally and per the guidance from the Ministry of Health, women were still allowed to opt for AZT in the PMTCTB+ study. Treatment response was monitored through routine VL testing at 6 and 12 months and annually thereafter using the Biocentric (Bandol, France) multi-manufacturer open platform for HIV-1 VL quantification on plasma samples. Stepped-up adherence counselling was performed in case of an elevated VL > 1000 copies/ml [13]. EID testing was performed using the Cobas® AmpliPrep/Cobas® TaqMan® v2.0 for the qualitative detection of HIV-1 from heel prick dried blood spots. Women missing their scheduled ART refill visits or their EID appointment at 6 weeks after birth were traced by phone as per national protocol.

Variables and definitions

First, for HIV+ pregnant treatment naïve women, the primary outcome was time from first ANC visit to ART initiation. Censoring occurred on the date of AZT initiation, transfer out of the study facilities, death, loss to follow-up (LTFU), and latest at 6 months after the first ANC visit. Second, for women commencing ART, the primary outcome was time to occurrence of the composite unfavourable endpoint LTFU (defined as ≥4.5 months without visit) or death. Censoring occurred at the last recorded clinic visit for transfer out and latest at the end of the observation period (18 September 2015). Six-month VL test utilization was defined as the proportion of women being on ART for at least 6 months who received a VL test between 6 to 12 months after the commencement of ART. Finally, EID utilization and HIV mother to infant transmission were described. Because the date of birth was often not recorded, EID was defined as any PCR measurement done between birth and the end of the observation period. HIV transmission was described for infants who had EID test results available. For all analyses, baseline variables were measured at the time of the first ANC visit. Same-day ART initiation was defined as patients starting ART on the day of HIV diagnosis. The study enrolment period was divided into 3 phases (early: 01–06/2013, mid: 07–12/2013 and late: 01–06/2014) to account for temporal trends.

Data management and statistical analyses

Trained data clerks entered patient information into an electronic study database. Clinical and socio-demographic data were obtained from facility-based registers and patient files. VL test results were obtained from the laboratory based electronic VL database, and birth outcomes and EID data from maternity records and child welfare registers. Baseline characteristics were described using frequency statistics and proportions. Kaplan-Meier estimates were computed and uni- and multivariate Cox proportional-hazards regression models built for time to ART initiation and treatment outcome analyses. All regression models were adjusted for baseline socio-demographic and clinical covariate information, and the final models were obtained through backwards stepwise regression and elimination of covariates with p > 0.15. All analyses were performed using STATA (version 12.1) [21].

Results

Baseline characteristics

Overall, 665 HIV-positive pregnant women attended a first ANC visit (Table 1) and 354 (53.2%) at primary care facilities. The median age was 26 years (IQR: 23, 30), the median CD4 count was 387 cells/μl (IQR: 264, 539), 506 (76.1%) had combined WHO stage I/II and 408 (61.4%) were newly diagnosed HIV+. The median gestational age was 22 weeks (IQR: 17, 26) and 131 (19.8%) were primigravida. Overall one third of patients were enrolled during each of the enrolment phases.

ART initiation

Of 665 HIV+ pregnant women, 496 (74.6%) initiated ART (of whom 47 transitioned from single AZT therapy), 70 (10.5%) opted for AZT and 99 (14.9%) received neither. Of the 496 who initiated ART, 454 (91.5%) were on a Tenofovir+Lamivudine+Efavirenz, 3 (0.6%) were on Zidovudine+Lamivudine+Nevirapine, 3 (0.6%) were on Zidovudine+Lamivudune+Efavirenz and 36 (7.3%)) were missing ART regimen data. The proportion of women initiating ART among all individuals increased from 150 (64.7%) to 198 (85.7%) between early to late study implementation phases. Kaplan-Meier estimates for same-day ART initiation was 34.1% (95%CI: 30.7–37.9) and for three-month ART initiation was 74.4% (95%CI: 71.1-77.7). The same-day and six-month ART initiation rate increased from 8.6% (95%CI: 5.6–13.0) to 58.4% (95%CI: 52.2–64.8) and 64.2% (95%CI 58.1–70.4) to 85.7% (95%CI 80.8–89.9; p < 0.001) respectively between early and late enrolment phases (Fig. 1).

In multivariate analysis (Table 1), women with CD4 ≥ 500 (aHR: 0.69, 95%CI 0.56–0.87), missing CD4 (aHR: 0.31, 95% 0.2–0.49) and missing WHO staging result (aHR: 0.40, 95% 0.31–0.52) were less likely to initiate ART. The only positive predictor of ART initiation was entry into the study in later phases (mid: aHR: 1.41, 95% 1.12–1.77; late: aHR: 2.36, 95% 1.89–2.94).

ART outcomes

Of 496 women initiated on ART, 250 (50.4%) were in care in the study clinics at the end of the observation period, 4 (0.8%) had died and 37 (7.5%) had transferred out. Of 205 (41.3%) women LTFU, 44/205 (21.5%) never returned for the first drug refill visit. Of 94/205 (45.9%) with recorded delivery date, 34 (36.2%) had the last drug refill visit before delivery. Kaplan-Meier estimated retention was 79.9% (95% CI 76–83.2), 70.7% (95% CI 66.4–74.6) and 52.9% (95% CI 47.6–57.9) at 6, 12 and 24 months. Retention between the CD4 categories was different only for the first 3 months after ART initiation (p = 0.01) but similar thereafter (p = 0.187). In the multivariate model (Table 2), ANC visit in the third trimester (aHR: 2.37, 95% CI 1.39–4.01), secondary care facility (aHR: 1.98, 95% CI 1.50–2.60) and later enrolment phases (mid aHR: 1.48, 95% CI 1.05–2.08; late aHR: 1.67, 95% CI 1.18–2.37) were associated with an increased risk of attrition while the risk was reduced for the age-group 25–34 years (aHR: 0.75, 95% 0.57–0.99). Following defaulter tracing, 34 (40.5%) of 84 mothers traced from those LTFU re-started ART after completion of the retention analysis, and their median time of treatment interruption was 5 months (IQR: 4.0, 7.3).

Viral load outcomes

Of 496 women initiated on ART, 373 were retained in care for at least 6 months, making them eligible for a first VL test. Of these 251 (67.3%) received a first VL test and 223/251 (88.8%) were virologically suppressed (< 1000 copies/mL).

Early infant diagnosis

Of 670 infants, 359 (53.6%) received a PCR EID HIV test. A test result was available for 320 (89.1%) infants, of whom 7 (2.2%) were HIV-positive: 3/278 (1.1%) for women on ART, 2/34 (5.9%) for women on AZT and 2/31 (6.5%) for women without ART/AZT; 4/141 (2.8%) for women with CD4 < 350, 1/94 (1.1%) for CD4 350-499 and 1/85 (1.2%) for CD4 ≥ 500. For the 3 infants who tested positive with their mothers on ART, all three women had a suppressed VL test at the time of delivery and the 3 infants received the EID test more than 2 months after delivery and were exclusively breastfed.

Discussion

The roll out of PMTCTB+ was found to be feasible in this setting. However, several challenges were encountered along the maternal treatment and infant diagnostic cascade. Overall, three quarters of eligible women initiated ART, but only half of them were retained on ART at two years. While maternal VL suppression was high and early mother to infant HIV transmission low, VL utilization and EID testing uptake was sub-optimal.

ART initiation rates were low at the beginning of the study but increased steadily over time. Several challenges encountered during the early implementation of PMTCTB+ may have played a role in this setting, such as; patients’ and health workers’ resistance to lifelong ART [20, 22, 23]. Other studies have also reported significant barriers to ART uptake for PMTCT [23,24,25] although this differs from the experience in Malawi where a nationwide rollout and sensitization may have improved awareness and uptake of the program [26]. As this was a pilot study, no national sensitization could be organized to promote ART acceptance specifically in women who were not eligible for lifelong ART under PMTCA [20]. In addition, AZT persisted as an option during the entire study period because PMTCTA remained the standard of care in the rest of the country. These issues were addressed in response to early poor ART uptake through repeated trainings for nurses and community health workers and through intensified community awareness and mobilization activities.

Only 53% of women were retained in care at 24 months. Attrition was highest among HIV+ women on ART at the secondary health care facility, among women who initiated ART during the last trimester of their pregnancy and for women with CD4 ≥ 500. These findings are in line with other studies [26,27,28,29,30,31]. A possible explanation is that women only initiated ART for the benefit of the unborn child, because they had limited understanding of the subsequent benefit of ART for their own health and in preventing transmission to their infant during breastfeeding [32, 33]. In addition, 9% of women receiving ART did not return for the first drug refill, similar to findings from another study in Ethiopia [31] which may reflect the importance of early treatment adherence support and retention messages especially for mothers with higher CD4 count at the start of their treatment and clinical follow-up [23].

The risk of attrition was also higher among women initiated on ART during the later enrolment phase which had a higher proportion of same-day ART initiations. Given that other observational studies have reported higher risk of attrition in same-day initiates [31, 34], we included this factor in the analysis as a possible predictor of attrition. Although no association was discovered, we still suggest that caution should be taken with same-day ART initiation as a public health approach and patient readiness should be taken into account [35].

In addition, context- and culture-specific factors probably play a major role in the attrition we observed. Many facilities are located close to the South African border. As pregnant women attending South African clinics are given incentives after delivery, it is possible that some mothers may have chosen to continue treatment there. Furthermore, in their culture many Swazi women continue to face structural barriers to ART initiation and continuation such as gender inequality, economic dependency and patriarchal social factors [36]. Women often return to their mother’s homestead for delivery and for the first few months of child rearing but move back to their own homes later. Future work could look into the role of migration in treatment discontinuation in this treatment group.

In this cohort, 67% of the women on ART received a first VL after 6–12 months; of these 89% had an undetectable VL. To our knowledge, only one other study has reported on VL outcomes of a PMTCTB+ cohort in sub-Saharan Africa and reported similar findings [37]. VL monitoring was still quite a novel practice for health workers and its routine use for treatment monitoring was still not fully established [38]. In addition, according to our data, women were often lost to follow-up before they became eligible to receive their first VL at 6 months after ART initiation. Nevertheless, the high proportion of VL suppression among those tested was encouraging and suggested good ART adherence in patients retained and receiving a VL test. This is critical if ART is to provide long term benefits to the mothers and reduce the risk of HIV transmission during breastfeeding [39,40,41].

EID test utilization was suboptimal at 54%. EID information was collected from child welfare registers available at the facilities. Other authors have discussed the problems with use of paper registers [42, 43]. The only way to identify infants was if their mothers’ information was included in the register, because of this, we may have missed some poorly documented EID tests. According to program managers, often infants are brought to the facility by another care giver (e.g.: grandmother), who may not have the mother’s personal details. Healthcare workers prefer not to ask caregivers (other than the biological mother) for permission to perform the HIV test on the child, in order to avoid unintentional disclosure of the mothers’ status. HIV status assessment in children is expected to improve because Swaziland has since adopted the WHO strategy to test all infants for HIV regardless of exposure at 9 months after birth [44].

Vertical mother to child transmission rates were low (2.2%) at 6 weeks (and comparable to the national estimate of 2.4% [19]) and appeared lower when the mother received ART (1.1%) when compared to AZT (5.9%) and those without AZT/ART (6.5%). Transmission rates are similar to findings from other studies [45,46,47]. These data, however, need to be interpreted with caution because EID results were available for only less than half of the eligible children.

This study has several limitations. First, routine paper registers and patient files were the main data source. Differences in recording practices may have led to varying completeness and quality of data which limits internal validity. This incompleteness also meant that we could not include all possible confounding factors (e.g. income, marital status and education) in our analyses limiting the robustness of our findings. Second, misclassification of the treatment outcome was possible. Although national standard operating procedures required a routine phone call three days after a missed appointment in order to re-engage women into care or ascertain the outcome, 60% of women could not be contacted due to incorrect contact details (phone numbers did not exist, were unreachable, or somebody else answered the phone). Weak ascertainment of ART outcomes and suboptimal implementation of physical defaulter tracing activities may have inflated attrition rates [48, 49]. Third, this observational study was likely affected by temporal trends such as patient and community mobilization as well as countrywide adoption and scale-up of PMTCTB+ in the second half of 2014. We addressed this by dividing the study implementation period into 3 phases. External validity is a strength of this study. PMTCTB+ was implemented under routine conditions in predominantly rural government clinics. Therefore, limitations faced in this high HIV prevalence setting likely apply to many other contexts in southern Africa.

Conclusions

Accelerated access to ART for pregnant women (PMTCTB+) was feasible within a pilot implementation project under routine public health service. While ART initiation rates increased over time, high rates of ART attrition emerged as a programmatic challenge. Documented maternal VL suppression was high and vertical HIV transmission low, however, the uptake for VL and EID testing was suboptimal. This, together with high attrition makes judgement of the magnitude of the public health impact uncertain. Specific aspects in PMTCTB+ programming need further strengthening, in particular, paying attention to community sensitisation and training of staff, as well as to the continuity of care and follow-up for both the mothers and their infants.

References

Coutsoudis A, Dabis F, Fawzi W, Gaillard P, Haverkamp G, Harris DR, Jackson JB, Leroy V, Meda N, Msellati P, Newell ML, Nsuati R, Read JS, Wiktor S. Late postnatal transmission of HIV-1 in breast-fed children: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:2154–66.

Dabis F, Bequet L, Ekouevi DK, Viho I, Rouet F, Horo A, Sakarovitch C, Becquet R, Fassinou P, Dequae-Merchadou L, Welffens-Ekra C, Rouzioux C, Leroy V. Field efficacy of zidovudine, lamivudine and single-dose Nevirapine to prevent peripartum HIV transmission. JAIDS. 2005;19:309–18.

de Vincenzi I. Triple antiretroviral compared with zidovudine and single-dose Nevirapine prophylaxis during pregnancy and breastfeeding for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 (Kesho bora study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:171–80.

Leroy V, Sakarovitch C, Cortina-Borja M, McIntyre J, Coovadia H, Dabis F, Newell ML, Saba J, Gray G, Ndugwa C, Kilewo C, Massawe A, Kituuka P, Okong P, Grulich A, von Briesen H, Goudsmit J, Biberfeld G, Haverkamp G, Weverling GJ, Lange JM. Is there a difference in the efficacy of peripartum antiretroviral regimens in reducing mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Africa? JAIDS. 2005;19:1865–75.

Marston M, Becquet R, Zaba B, Moulton LH, Gray G, Coovadia H, Essex M, Ekouevi DK, Jackson D, Coutsoudis A, Kilewo C, Leroy V, Wiktor S, Nduati R, Msellati P, Dabis F, Newell ML, Ghys PD. Net survival of perinatally and postnatally HIV-infected children: a pooled analysis of individual data from sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:385–96.

Nduati R, John G, Mbori-Ngacha D, Richardson B, Overbaugh J, Mwatha A, Ndinya-Achola J, Bwayo J, Onyango FE, Hughes J, Kreiss J. Effect of breastfeeding and formula feeding on transmission of HIV-1: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2000;283:1167–74.

Thior I, Lockman S, Smeaton LM, Shapiro RL, Wester C, Heymann SJ, Gilbert PB, Stevens L, Peter T, Kim S, van Widenfelt E, Moffat C, Ndase P, Arimi P, Kebaabetswe P, Mazonde P, Makhema J, McIntosh K, Novitsky V, Lee TH, Marlink R, Lagakos S, Essex M. Breastfeeding plus infant zidovudine prophylaxis for 6 months vs formula feeding plus infant zidovudine for 1 month to reduce mother-to-child HIV transmission in Botswana: a randomized trial: the Mashi study. JAMA. 2006;296:794–805.

The TEMPRANO ANRS 12136 Study Group. A trial of early Antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):808–22.

Group TISS. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795–807.

Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, Thomas KK, Stevens W, Cohen CR, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet Lond Engl. 2010;375(9731):2092–8.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505.

Albert J, Berglund T, Gisslén M, Gröön P, Sönnerborg A, Tegnell A, et al. Risk of HIV transmission from patients on antiretroviral therapy: a position statement from the Public Health Agency of Sweden and the Swedish reference Group for Antiviral Therapy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46(10):673–7.

WHO | Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2015 Sep 29]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/download/en/

First Findings Released from Swaziland HIV Incidence Measurement Survey | Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health [Internet]. [cited 2015 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.mailman.columbia.edu/public-health-now/news/first-findings-released-swaziland-hiv-incidence-measurement-survey

The Kingdom of Swaziland. Swaziland country report on monitoring the political declaration on HIV and AIDS: UNAIDS; 2012. http://files.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2012countries/ce_SZ_Narrative_Report[1].pdf

Swaziland Ministry of Health. Last sentinel survey: ANC sentinel surveillance: Swaziland Ministry of Health; 2010.

WHO. Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating Pregnant Women and Preventing HIV Infection in Infants: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach: 2010 Version [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004 [cited 2017 Mar 28]. (WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304944/

WHO. Programmatic update: Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating Pregnant Women and Preventing HIV Infection in Infants [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2017 Sep 3]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/PMTCT_update.pdf

Swaziland Ministry of Health. Swaziland global AIDS response progress reporting. 2014.

Parker LA, Jobanputra K, Okello V, Nhlangamandla M, Mazibuko S, Kourline T, et al. Implementation and operational research: barriers and facilitators to combined ART initiation in pregnant women with HIV: lessons learnt from a PMTCT B+ pilot program in Swaziland. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2015;69(1):e24–30.

StataCorp. Stata statistical software. College Station: StataCorp LP; 2011.

Kourline T. Initiation sous traitement antirétroviral des femmes enceintes et allaitantes: Le rôle du personnel soignant et des partenaires. Expérience d’une étude pilote PTME B+ au Swaziland. Montpellier: Poster presented at: Afra VIH; 2014.

Katirayi L, Chouraya C, Kudiabor K, Mahdi MA, Kieffer MP, Moland KM, et al. Lessons learned from the PMTCT program in Swaziland: challenges with accepting lifelong ART for pregnant and lactating women - a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1119.

Gourlay A, Birdthistle I, Mburu G, Iorpenda K, Wringe A. Barriers and facilitating factors to the uptake of antiretroviral drugs for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18588.

Gourlay A, Wringe A, Todd J, Cawley C, Michael D, Machemba R, et al. Uptake of services for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in a community cohort in rural Tanzania from 2005 to 2012. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):4.

Ministry of Health, Governemt of Malawi. Integrated HIV program report July—September 2012. 2012.

Fatti G, Grimwood A, Bock P. Better antiretroviral therapy outcomes at primary healthcare facilities: an evaluation of three tiers of ART services in four south African provinces. PLoS One. 2010;5(9):e12888.

Carmone A, Bomai K, Bongi W, Frank TD, Dalepa H, Loifa B, et al. Partner testing, linkage to care, and HIV-free survival in a program to prevent parent-to-child transmission of HIV in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:24995.

Tenthani L, Haas AD, Tweya H, Jahn A, van Oosterhout JJ, Chimbwandira F, et al. Retention in care under universal antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women ('Option B+’) in Malawi. AIDS Lond Engl. 2014;28(4):589–98.

Miller K, Muyindike W, Matthews LT, Kanyesigye M, Siedner MJ. Program implementation of option B+ at a President’s emergency plan for AIDS relief-supported HIV clinic improves clinical indicators but not retention in Care in Mbarara, Uganda. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31(8):335–41.

Mitiku I, Arefayne M, Mesfin Y, Gizaw M. Factors associated with loss to follow-up among women in option B+ PMTCT programme in Northeast Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. J Int AIDS Soc [Internet]. 2016 21 [cited 2016 Aug 8];19(1). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4803835/

McLean E, Renju J, Wamoyi J, Bukenya D, Ddaaki W, Church K, et al. “I wanted to safeguard the baby”: a qualitative study to understand the experiences of option B+ for pregnant women and the potential implications for “test-and-treat” in four sub-Saharan African settings. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93(Suppl 3). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5739848/

Clouse K, Schwartz S, Van Rie A, Bassett J, Yende N, Pettifor A. “What they wanted was to give birth; nothing else”: barriers to retention in option B+ HIV care among postpartum women in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2014;67(1):e12–8.

Chan AK, Kanike E, Bedell R, Mayuni I, Manyera R, Mlotha W, et al. Same day HIV diagnosis and antiretroviral therapy initiation affects retention in option B+ prevention of mother-to-child transmission services at antenatal care in Zomba District, Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20672.

Ford N, Migone C, Calmy A, Kerschberger B, Kanters S, Nsanzimana S, Mills EJ, Meintjes G, Vitoria M, Doherty M, Shubber Z. Benefits and risks of rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2018;32(1):17-23.

Dlamini-Simelane TTT, Moyer E. “Lost to follow up”: rethinking delayed and interrupted HIV treatment among married Swazi women. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(2):248–56.

Myer L, Phillips TK, McIntyre JA, Hsiao N-Y, Petro G, Zerbe A, et al. HIV viraemia and mother-to-child transmission risk after antiretroviral therapy initiation in pregnancy in cape town, South Africa. HIV Med. 2017;18(2):80–8.

Jobanputra K, Parker LA, Azih C, Okello V, Maphalala G, Jouquet G, et al. Impact and programmatic implications of routine viral load monitoring in Swaziland. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2014;67(1):45–51.

Redd AD, Wendel SKJ, Longosz AF, Fogel JM, Dadabhai S, Kumwenda N, et al. Evaluation of postpartum HIV superinfection and mother-to-child transmission. AIDS Lond Engl. 2015;29(12):1567–73.

Ngoma MS, Misir A, Mutale W, Rampakakis E, Sampalis JS, Elong A, et al. Efficacy of WHO recommendation for continued breastfeeding and maternal cART for prevention of perinatal and postnatal HIV transmission in Zambia. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:19352.

Blumental S, Ferster A, Van den Wijngaert S, Lepage P. HIV transmission through breastfeeding: still possible in developed countries. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):e875–9.

Gourlay A, Wringe A, Todd J, Michael D, Reniers G, Urassa M, et al. Challenges with routine data sources for PMTCT programme monitoring in East Africa: insights from Tanzania. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:29987.

Mate KS, Bennett B, Mphatswe W, Barker P, Rollins N. Challenges for routine health system data management in a large public programme to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in South Africa. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5483.

Swaziland Ministry of Health. Swaziland Integrated HIV Management Guidelines. 2015.

Ekouevi DK, Coffie PA, Becquet R, Tonwe-Gold B, Horo A, Thiebaut R, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in pregnant women with advanced HIV disease and pregnancy outcomes in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. AIDS Lond Engl. 2008;22(14):1815–20.

Hussain A, Moodley D, Naidoo S, Esterhuizen TM. Pregnant women’s access to PMTCT and ART services in South Africa and implications for universal antiretroviral treatment. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e27907.

Njom Nlend AE, Same Ekobo C, Bagfegue Ekani B, Epée Ngoue J, Tetang Ndiang S, Tchinde Toussi F, et al. Preventing HIV-1 transmission in breastfed infants in low resource settings: early HIV infection and late postnatal transmission in a routine prevention of mother-to-child transmission program in Yaounde, Cameroon. J Trop Pediatr. 2013;59(5):387–92.

Wilkinson LS, Skordis-Worrall J, Ajose O, Ford N. Self-transfer and mortality amongst adults lost to follow-up in ART programmes in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health TM IH. 2015;20(3):365–79.

McMahon JH, Elliott JH, Hong SY, Bertagnolio S, Jordan MR. Effects of physical tracing on estimates of loss to follow-up, mortality and retention in low and middle income country antiretroviral therapy programs: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56047.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all women and infants, and health workers participating in the study. We would also like to thank Marta Balinska for her comments and editing support.

Funding

Viral load testing was funded by UNITAID.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available as consent for the sharing of this data was not sought from the participants as there was no data sharing requirement at the time.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design and protocol development: LAP, KJ, RT, NS, BN, BK. Implementation of the research: SS, EM, KJ, BK, LAP, MN, NS, BN, SMH, MP, SMK, BR, CJ, IC, RT. Statistical analysis: DE, BK. Interpretation of findings: BK, DE, IC, RT, NS, MN, BN, KJ, SMH, LAP, SS, EM, MP, SMK, BR, CJ. Writing first draft of the manuscript: DE, BK, IC. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Scientific and Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health of Swaziland, and the Ethics Review Board of Médecins Sans Frontières. Participation was based on informed consent. Written or verbal consent was obtained by a study nurse from all participants depending on their literacy level. Participants kept the original consent form and a copy remained in their clinical file for future reference.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Etoori, D., Kerschberger, B., Staderini, N. et al. Challenges and successes in the implementation of option B+ to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV in southern Swaziland. BMC Public Health 18, 374 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5258-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5258-3