Abstract

Background

Genetic testing for risk of hereditary cancer can help patients to make important decisions about prevention or early detection. US and UK studies show that people from ethnic minority groups are less likely to receive genetic testing. It is important to understand various groups’ awareness of genetic testing and its acceptability to avoid further disparities in health care. This review aims to identify and detail awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes towards genetic counselling/testing for cancer risk prediction in ethnic minority groups.

Methods

A search was carried out in PsycInfo, CINAHL, Embase and MEDLINE. Search terms referred to ethnicity, genetic testing/counselling, cancer, awareness, knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions. Quantitative and qualitative studies, written in English, and published between 2000 and 2015, were included.

Results

Forty-one studies were selected for review: 39 from the US, and two from Australia. Results revealed low awareness and knowledge of genetic counselling/testing for cancer susceptibility amongst ethnic minority groups including African Americans, Asian Americans, and Hispanics. Attitudes towards genetic testing were generally positive; perceived benefits included positive implications for personal health and being able to inform family. However, negative attitudes were also evident, particularly the anticipated emotional impact of test results, and concerns about confidentiality, stigma, and discrimination. Chinese Australian groups were less studied, but of interest was a finding from qualitative research indicating that different views of who close family members are could impact on reported family history of cancer, which could in turn impact a risk assessment.

Conclusion

Interventions are needed to increase awareness and knowledge of genetic testing for cancer risk and to reduce the perceived stigma and taboo surrounding the topic of cancer in ethnic minority groups. More detailed research is needed in countries other than the US and across a broader spectrum of ethnic minority groups to develop effective culturally sensitive approaches for cancer prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Several types of cancer have been found to be associated with hereditary gene mutations [1, 2]. Specifically, mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are known to be linked to breast, ovarian [3, 4], and prostate cancer [5]. Over the past 20 years, the scientific understanding of cancer related genetics has greatly improved. Within several European countries and the US, patients diagnosed with a potentially hereditary cancer or with a strong family history can receive genetic counselling and testing to establish whether they have an inherited cancer gene mutation. Knowledge about personal cancer risk can help currently healthy individuals to make health care decisions, such as whether to attend regular screening or opt for surgery, in order to help reduce the risk of developing cancer [6].

Public attitudes towards genetic testing for the risk of diseases, including cancer, have been found to be generally positive [7,8,9]. In a US study, 97% of participants indicated that they were at least somewhat interested in the topic of genetic testing and the majority had positive attitudes about genetic research and approved of the use of genetic testing in the detection of diseases [9]. Positive attitudes towards genetic testing are also reported in a Dutch survey study that found that 64% of participants believed genetic testing would help people to live longer [8]. However, there are also concerns amongst the general public that genetic test results could be used to discriminate against those with a genetic predisposition for illness [9] and that genetic testing could result in people being labelled as having “good” or “bad” genes [8].

The incidence and burden of cancer varies between ethnic groups. In the UK, incidence of breast cancer is higher amongst White women compared to all other ethnic groups [10], but Black men have higher rates of prostate cancer than White men [11]. Similarly, in the US overall cancer incidence and mortality has been found to be highest in Black men compared to other ethnic groups, and whilst Black women have a lower incidence of breast cancer than White women they have a worse mortality rate [12]. In the US Hispanics are reported to have lower incidence and mortality rates of cancer than White Americans [13], and evidence suggests that whilst Asian Americans also tend to have lower cancer rates than Whites, increasing incidence rates have been detected between 1990 and 2008 for breast, colorectal, and uterine cancer amongst several subgroups of Asian American women [14].

Despite the potential health benefits of cancer susceptibility testing, ethnic minority groups have been found to be underserved by genetic services and underrepresented in research in Europe and the US [15,16,17,18]. In a UK study, only 3% of patients referred to 22 regional genetics services were from an ethnic minority group [19]. Armstrong et al. [20] also found that women pursuing BRCA1/2 genetic testing in a US study were significantly more likely to be White, and Levy et al. [21] report that significantly fewer Black and Hispanic women with a new diagnosis of breast cancer and at risk of carrying a BRCA gene mutation had genetic testing.

A previously published review investigating what may hinder African, White Irish, and South Asian ethnic minority groups’ access to cancer genetic services found potential barriers included low awareness and knowledge of genetic testing and available services, language barriers, stigma associated with being at risk, fatalistic views of cancer, anticipation of negative emotions, uncertainty about the information provided, and mistrust of how data would be used [22]. The current review aims to investigate factors that might act as barriers or facilitators to the uptake of genetic testing across diverse ethnic minority groups. The review fills a critical knowledge gap by focusing on awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes towards genetic testing for cancer susceptibility, and reasoning for and against testing by people from Black and ethnic minority backgrounds.

Methods

The systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines and an a priori published protocol (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ CRD42016033485).

Eligibility

The review includes primary studies that aimed specifically to investigate ethnic minority groups’ awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes, or provide information on participants’ reasons for/against interest, intentions or actual uptake of genetic testing/counselling for personal cancer risk. Studies with a focus on genetic testing or genetic counselling were included as currently these services often go hand-in-hand and we wanted to see if there were important attitudes affecting uptake. We included quantitative and qualitative studies conducted in Europe, the US or Australia, and published in English in a peer reviewed journal from the year 2000 onwards.

Research that investigated awareness/attitudes/perceptions of direct-to-consumer genetic testing, or that only investigated participants’ perceptions of cancer or their experience of receiving genetic information were excluded from the review. Articles that evaluated recruitment methods, or interventions to raise awareness/knowledge of genetic testing amongst ethnic minority groups were also excluded. Studies focusing mainly on Ashkenazi Jewish participants were not included as this group is known to have an increased risk of carrying BRCA1/2 gene mutations which might uniquely influence their knowledge/interest/attitudes to genetic testing. Ashkenazi Jewish women also have a high level of acceptance of genetic testing [23, 24]. Unpublished research was not sought for this review.

Study search

Four databases were searched in December 2015: PsycInfo (OVID interface), CINAHL (EBSCO interface), Embase (OVID interface) and MEDLINE (OVID interface). The search terms included a combination of thesaurus (MeSH) terms and keywords such as: ‘ethnic’ or ‘minorit*’ or ‘African’ or ‘Asian’, combined with ‘know*’ or ‘aware*‘or ‘attitude*’ or ‘perception*’ and ‘cancer’ and ‘genetic testing’ or ‘genetic counselling’. [See Additional file 1 for full lists of search terms.]

Study selection

Figure 1 presents the article selection process. Study articles were independently selected by two researchers [KH & MF]. Articles were initially identified by the titles and abstracts and those which appeared eligible were reviewed in full. A reference list search was also conducted to identify additional articles. Any disagreements or uncertainties on the inclusion of studies were brought to a third researcher [AL] to make a final decision.

Data extraction and analysis

A data extraction tool was designed to gather relevant information on the study design, methods, and results on awareness, knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions relating to genetic testing/counselling for cancer risk.

A thematic synthesis of the qualitative research was carried out in line with recommendations by Thomas and Harden [25]. The synthesis involved extracting and analysing each article’s results section, including direct quotes. An iterative process of re-reading and coding the text was used, and a coding manual was produced based on the themes identified. Once coding was completed a second researcher [MF] independently analysed 20% of the qualitative data using the coding manual. The analysis was organised using the software package NVivo (version10).

Quality assessment

The quality of each study was assessed using tried and tested tools designed by Kmet et al. [26] for quantitative and qualitative research. The assessment tool criteria included an assessment of the description of the study objective, design, methods, data analysis, and conclusions. Criteria are scored using a 3-point Likert scale: 0 (criteria not fulfilled); 1(partial fulfilment); 2 (criteria fulfilled). A final score is calculated by adding all relevant criteria scores and dividing by the total possible score for each study. The included articles were independently quality assessed by two researchers [KH & MF]. When disagreements arose they were discussed until consensus was reached.

Results

For the purpose of the review we have standardised the terms used to refer to the groups included, see Table 1 for a key and frequencies of groups included across the studies. Table 2 summarises the 31 quantitative studies and the results on ethnic minority groups’ awareness, knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions in regards to genetic counselling (n = 2), genetic testing (n = 27), or both (n = 2) for cancer risk. Measures used in the studies were often non validated study specific instruments and due to their heterogeneity across different ethnic groups and in reference to different cancers a meta-analysis of the results was not possible [see Additional file 2 for a list of the measures used]. Table 3 presents a summary of the 10 qualitative and mixed methods studies, noting themes as originally identified. Of these 10 qualitative studies, 5 involved interviews, 4 involved focus groups and 1 used both focus groups and in-depth interviews. The tables have been arranged by ethnicity and cancer type.

A total of 82,432 individuals from African American, Hispanic, Asian American, White, and Chinese Australian ethnic groups took part in the 41 studies reviewed. Thirty-nine of the forty-one studies were conducted in the US and two were conducted in Australia. Breast and ovarian cancer or BRCA genetic testing were most frequently referred to within the reviewed research, twelve referred to a number of cancers or cancer in general, three referred to prostate cancer, two to colon/colorectal cancer, and one to lung cancer.

Quantitative studies

Awareness

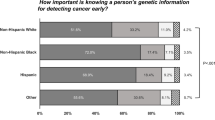

Awareness was measured in two ways across 15 studies; either a dichotomous Yes/No question [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] or a measure asking participants how much they had heard/read about genetic testing [36,37,38,39,40,41]. Figure 2 presents the percentage of participants who indicated awareness or having heard/read a fair amount/a lot about genetic testing for cancer risk by study and ethnic group. Within general population samples of Hispanics, awareness of genetic testing for cancer risk ranged from 7.7% of Spanish only speaking Hispanics [28] to 27.9% of internet users [30]. Across two samples of Hispanics with a high risk of cancer due to family history or a personal experience of cancer, 46.7% [38] and 47.1% [41] were aware of genetic counselling for cancer risk in general; awareness of genetic counselling for colon, breast, and ovarian cancer varied. Whilst Gammon et al. [27] found 43.1% of a Hispanic sample were aware of BRCA1/2 testing, this sample included only high cancer risk participants of whom several had already had genetic testing.

Awareness of genetic testing/counselling for cancer risk across ethnic groups. The bar graph presents the percentage of participants aware of genetic testing or counselling for cancer risk across ethnic groups. *Indicates percentage of participants that reported having read/heard a fair amount/a lot about genetic testing. BC/OC = breast/ovarian cancer; GT = genetic testing; GC = genetic counselling

Amongst African Americans, awareness of genetic testing for cancer risk ranged from 29% [30] to 54% in general population samples [35]. Awareness of the BRCA1/2 gene and mutation testing appears to be particularly low, one study [35] reported that only 12% were aware and another [33] reported that 25% of African American participants were aware. Two studies reported that around 25% of Asian Americans were aware of genetic testing for cancer risk [31, 32].

Five studies reported that awareness significantly differed by ethnicity, with more White participants being aware of genetic testing for cancer risk than Hispanics, African Americans, and Asian Americans [29, 30, 32, 33, 40]. Vadaparampil et al. [34] also reported that whilst 20% of their Hispanic sample were aware of genetic testing for cancer risk, awareness varied by ethnic subgroups.

Only one study assessed whether awareness was associated with intentions to have genetic counselling, and found no significant association [41].

Knowledge

Eight of the included studies measured knowledge of hereditary cancer genetics within samples at an increased risk for cancer based on family history and including individuals with a personal cancer diagnosis [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. Figure 3 presents the average percentage of correctly answered knowledge questions across the studies. Findings suggest that knowledge was varied but limited amongst African Americans, with between 30% and 70% of questions answered correctly on average across five studies [42,43,44,45,46]. Two studies suggested that Hispanic participants also had limited knowledge, with scores of approximately 5 out of 11 for hereditary breast cancer knowledge [47, 48], although a high average score of 43.8 out of 55 was observed for genetic counselling knowledge in a third [41].

Only Donovan and Tucker [42] found a significant difference between African American and White participants’ scores on cancer genetics knowledge, indicating lower knowledge in the African American group. However the overall difference between scores was small, with a mean score of 7.7 out of 14 for Whites and 7.0 for African American.

High cancer genetics knowledge was found to be a significant predictor of genetic testing uptake in one study with African Americans [44]. In another study, those who participated in genetic counselling and testing had significantly higher scores for knowledge of cancer genetics than those who accepted neither, however cancer genetics knowledge did not reach significance as a predictor of genetic testing uptake [45]. Three other studies found no associations between cancer genetics knowledge and interest in or intentions to have genetic testing [41,42,43].

Attitudes and perceptions

Several different measures of attitudes/beliefs/perceptions regarding genetic testing or counselling were used, although similar items were used across these. Some studies reported attitude scores and others reported the number or percentage of participants who agreed with each statement. Ten studies reported that African American and Hispanic participants highly endorsed statements about the benefits of genetic counselling/testing for cancer risk, whilst endorsing limitations to a lesser extent [36,37,38, 41, 42, 45, 47, 49,50,51]. The results indicate that overall participants had positive attitudes and perceived several benefits of genetic testing.

Highly endorsed benefits of genetic counselling/testing for cancer risk included: to help make decisions on (enhanced) screening (endorsed by 81–100%) [36, 42, 43, 45, 49, 50]; to motivate self-examination (endorsed by 90–92%)[43, 45, 49]; receipt of information for family/being able to help family and children (endorsed by 38–99%) [27, 36, 38, 41, 43, 45, 47, 49, 52]; to reduce concern about cancer (endorsed by 60–90%) [38, 41, 43, 45, 49]; to reduce uncertainty (endorsed by 68–100%) [42, 43, 50]; to provide a sense of personal control (endorsed by 67–79%) [37, 43, 45, 49]; to help plan for the future (endorsed by 66%) [36, 52]. More variation was seen in attitudes towards benefits such as: to help make important life decisions (endorsed by 21–88%) [36, 41, 43, 45, 49, 50]; to provide reassurance (endorsed by 42–80% of participants) [38, 50, 52, 53]; to help with cancer prevention (endorsed by 31–88%) [27, 33, 50]; and to help make decisions about preventative surgery (endorsed by 44–77%) [41, 43, 45, 50]. Similarly, Kinney et al. [44] report that, when asked for reasons why they enrolled for genetic testing, participants cited family/personal motives (62%), information (28%), and society (9%).

Some of the most frequently endorsed limitations or barriers to genetic testing/counselling included: anticipated increased worry about offspring/relatives if test result is positive (endorsed by 53–95%) [38, 41, 43, 45, 49]; anticipated personal emotional reaction if test result is positive e.g. worry, fear, anger (endorsed 31–75%) [27, 36,37,38, 43, 45, 49, 52, 53]; concern about family’s reaction or impact on family (endorsed by 27–52%) [36, 49, 50, 52]; concerns about confidentiality (endorsed by 12–72%) [40, 42, 45, 49, 50]; concern about jeopardising/losing insurance (endorsed by 11–58%) [33, 36, 38, 41, 43, 45, 47, 49, 50]; cost (endorsed by 32–40%) [27, 47]; and feeling unable to handle the test emotionally (endorsed by 3–40%) [40, 42, 49, 50]. Reported reasons for a lack of interest/intention to pursue testing included cost, time, worry that others would find out, belief the results could be wrong, worry about increased risk, concern about discomfort, concern about discrimination, not wanting blood taken, logistical reasons, personal reasons, and having heard negative experiences of others who had undergone testing [44, 54, 55].

In studies comparing ethnic groups, results suggest that those from ethnic minority groups may hold less positive views or have greater concerns about genetic counselling/testing compared to White participants. Peters et al. [33] found that compared to White participants, African Americans were less likely to endorse health benefits of genetic testing and were more likely to believe that the government would use test results to label groups as inferior, however there were no other significant differences between the groups on attitudes towards insurance and job discrimination due to genetic test results. Sussner et al. [56] also reported that foreign born African American participants anticipated a more negative emotional reaction to genetic testing than those born in the US. Thompson et al. [40] found that African Americans and Latinas had significantly higher medical mistrust than Whites, and were more likely to believe that genetic test results would be used to show that their ethnic group is not as good as others, or to interfere with the natural order of things. Latinas with lower levels of acculturation and heightened medical mistrust also cited more barriers to genetic testing [39]. However, whilst Armstrong et al. [57] found that significantly more African Americans had high healthcare mistrust, there was no significant difference between African American and White participants’ willingness to undergo cancer risk genetic testing across several hypothetical scenarios.

Attitudes and perceptions were associated with uptake, interest, or intentions to have genetic testing in ten studies. Thompson et al. [45] reported that those who attended genetic counselling/testing perceived significantly fewer barriers and had more intrusive thoughts of breast cancer than those who did not. Similarly, Donovan and Tucker [42] reported that being at least somewhat interested in genetic testing was associated with more positive beliefs. Seven studies found that perceived high risk of cancer or of being a cancer gene mutation carrier was associated with acceptance of genetic testing or interest/intentions to test [41,42,43,44, 50, 53, 58]; however, one study reported that perceived cancer susceptibility was negatively associated with intentions [54]. Whilst Hughes et al. [59] found higher fatalistic beliefs about cancer in genetic test accepters than decliners, Myers et al. [54] indicated a negative association between fatalism about prostate cancer prevention and intentions to receive prostate cancer testing to find out about personal risk. Other attitudes and perceptions positively associated with genetic testing uptake or interest/intentions included the absence of the belief that testing leads to discrimination, reassurance from testing [53], belief in efficacy of screening [54], perceiving that it is good to know future risk, and believing in control through knowledge [37].

Qualitative studies

The 10 qualitative studies included 31 Chinese Australians, 17 Asian Americans, 120 African Americans, and 163 Hispanics. The majority of participants were female and were at high risk of cancer based on family history or had a diagnosis of cancer, one study used a sample of the general population [35]. The thematic synthesis of the qualitative studies identified five broad themes: information deficits; cancer related anxiety; positive and negative attitudes and perceptions; family; and service provision and access.

Information deficits

Although some studies indicated that participants had good awareness and knowledge of hereditary cancer and the involvement of genetics, these participants tended to be those who had experienced cancer themselves or in a close family member [60, 61], or had previously attended genetic counselling [62, 63].

“Genes have a big part in us having cancer. My family has a higher chance of getting cancer compared to other families as many of our family members had cancer.”

Chinese Australian, Eisenbruch et al. [62]

Several studies including Chinese Australian, Hispanic, and African American samples reported that the majority of participants had low awareness and knowledge about the importance of genetics in cancer, BRCA, and genetic testing [52, 60, 61, 63,64,65,66,67]. Some confusion on the difference between genetic counselling and genetic testing was identified [61, 65]. Generational differences in awareness, knowledge, and beliefs were observed in studies with Hispanic and Chinese Australian samples, indicating that older generations were less aware and perhaps less open to genetic testing for cancer risk [61,62,63,64]. Some Chinese Australian participants reported that older generations and those with traditional beliefs would not accept that mutated genes can be passed through generations, attributing the development of illness instead to bad luck or past bad deeds [62, 64]. The lack of understanding about hereditary cancer and unfamiliarity with genetic testing could act as a barrier to testing. Participants across several studies expressed a need for interventions, campaigns, and the provision of information to increase awareness and knowledge of cancer and genetic testing [35, 52, 60, 61, 65].

“Nobody knows it [genetic testing]. They are so far away [from Western medicine]. The mammogram is coming out but this is the first time I heard about the gene test.”

Asian American female, Glenn et al. [63]

“Black people aren’t into that yet. We need to know more about it so it will not seem so farfetched.”

African American female, Matthews et al. [52]

Closely linked to participants’ low awareness and knowledge of cancer and genetic testing were the misconceptions held, including believing that genetic counselling prevents cancer [65], stress causes cancer [52, 63], cancer is contagious [62], injuries cause cancer [67], and focusing or worrying about cancer causes it to develop [52, 62, 64]. It is highlighted that some of these beliefs may make people less willing to discuss cancer or attend cancer services.

“I have heard that if you hit your breasts, it could cause cancer—I saw a woman who got cancer after being hit with a bottle on her breast. My mother hit her stomach and then she got cancer in her uterus. The underwires in bras are not good and they harm your breast tissue and cause cancer. I take them out.”

Hispanic female, Vadaparampil et al. [67]

Cancer related anxiety

Four studies found that African American and Hispanic participants had fatalistic views of cancer, which they perceived to be an illness that cannot be cured and is associated with death [52, 61, 65, 66]. Across all the included ethnic groups participants associated emotions such as worry, anxiety, and fear with cancer and genetic testing [35, 52, 60, 61, 63,64,65,66,67]. Participants expressed that fear of cancer and knowing their cancer risk was a deterrent to genetic testing [35, 52, 60, 61, 63, 65,66,67]. Participants anticipated experiencing anxiety whilst undergoing genetic counselling/testing [52, 64] and worried about the potential emotional impact that a positive test result would have on them [52, 67]. Some Hispanics reported that at times embarrassment prevented them from seeking medical help and attending cancer screening [63, 66]. Sheppard et al. [60] also found that women were fearful of making decisions about managing cancer risk after testing.

“… I think it will be harder for them to find out that they have a gene or a mutation that may cause...their body to develop cancer...in the future, and so I think for a lot of people just knowing that they have the mutation will be a lot more of anxiety source than actually helpful…”

Hispanic, Kinney et al. [66]

However, within a Hispanic community, Sussner et al. [61] found that younger generations were less fatalistic about cancer and were more enthusiastic towards genetic counselling.

“But now the word cancer is different from before…before people were ashamed, now they believe they will beat it, it was once a taboo.”

Hispanic female, Sussner et al. [61]

Positive and negative attitudes and perceptions

Interest in and positive attitudes towards genetic testing for cancer susceptibility were identified [60, 63, 66]. Personal health benefits, such as cancer prevention, early detection, and risk management, were highlighted as main benefits of genetic counselling/testing by African American, Hispanic, and Asian American participants [35, 52, 63, 65, 66]. Some participants felt that genetic testing would help to motivate them to be proactive towards their health and take action by making positive behavioural changes [35, 65] and others considered the knowledge gained from genetic testing to be empowering [61, 65].

Benefits of genetic testing included “the opportunity for early detection, instead of waiting until the cancer develops.”

African American female, Adams et al. [35]

Some African American and Hispanic participants discussed their spirituality and God, this was not presented as a barrier to genetic testing but as a way of seeking guidance and coping [60, 61, 67]. Some participants felt that their spirituality was a motivator for finding out about their cancer risk [65].

“I do believe that everything is in God’s hands, regardless. But, I don’t think that my spiritual beliefs would prevent me from going. If anything, they would motivate me to go…”

African American female, Ford et al. [65]

Several negative attitudes and perceptions were held by participants in relation to cancer and genetic testing. Discussing illnesses such as cancer was described to be taboo by Chinese Australian, African American, and Hispanic participants [61, 62, 64, 66]. Participants explained that in their culture there is secrecy around cancer and individuals might not tell family if they had it [64, 66]. This taboo is closely linked to the perceived stigma of having an illness, feeling shame and not wanting to be treated differently. Fear of discrimination by employers and insurers, and stigma was discussed across several studies and highlighted as a deterrent to testing [35, 60, 61, 63, 65, 66]. Among Asian American and Chinese Australian participants, there were also concerns that receiving a positive genetic test result would create stigma that they have “bad genes”, which could impact on marriage prospects [63, 64].

“The stigma [would stop me from getting tested] because you always have a concern that somewhere this information is gonna reside on a computer somewhere; it may prevent you from getting employment, future insurance, or any number of things so that’s [my] concern. That is one thing that has stopped me from going ahead with testing.”

African American female, Sheppard et al. [61]

Five of the eight qualitative studies conducted in the US reported that participants, particularly African Americans, discussed mistrust and disillusionment in the health care system [35, 52, 61, 63, 65]. Participants expressed concerns that their genetic data would be misused [63], that they would be experimented on [52], and that tests were offered to make money rather than out of necessity [52, 61]. Medical mistrust among some African Americans was reported to stem from negative events in history [52] and the “Tuskegee effect” relating to the mistreatment of African American men in the Tuskegee Syphilis study [35]. Concerns regarding confidentiality, what would happen with genetic test results after testing, and concerns about private information being discovered by others without the donor’s permission were also highlighted as important issues [52, 61, 65].

“…I felt in the past that doctors have sent me for tests just to get money. I feel that I was put through something…really bad, going you know, put fear in me for something…just so the doctor could put the claim in and I would never trust. It was terrible…”

Hispanic female, Sussner et al. [61]

“One of my girlfriends who is so narrow-minded … would say ‘I wouldn’t let those people experiment [referring to genetic testing] on me’ …. Some of my other friends, who are not as narrowminded would think, ‘It’s best to find out all you can’… ‘Go for all the tests you can’ ”

African American female, Glenn et al. [63]

Only one study, involving Asian American participants, suggested that a cultural mismatch exists between genetic testing and their culture’s traditional medicine [63]. However, scepticism of genetic testing was identified amongst Hispanic participants who were unsure of the need for genetic testing and screening without having symptoms [66], and others who felt there was no point in knowing [67]. Some African Americans were unsure of the test accuracy or reliability for their ethnic group [35, 52]. Ford et al. [65] also reported that African American women who did not attend genetic counselling perceived few benefits.

Family

The theme of Family was raised in discussion by many participants and was described as both a motivator and a barrier to testing. Two studies reported that Hispanics identified a culture of prioritising family needs over their own, resulting in a lack of time to attend health appointments [61, 63] and therefore a potential barrier to attending genetic counselling or testing.

“The woman is meant to do everything, take care of the house, take care of this, take care of that, so health does go on the background…That’s how we were raised. You last, everybody else first”

Hispanic female, Sussner et al. [61]

However, helping others in society [60, 63] and family [35, 52, 60, 61, 63, 66] was cited as an important benefit and motivator for genetic testing across most groups. Some Hispanic participants also felt it was important that they act as role models by making health more of a priority and encouraging older women to attend genetic counselling [61].

“I was the first one diagnosed with breast cancer in my family, so I would be concerned about it for their sake to find out what was going on…so that’s what would motivate me, family.”

African American female, Sheppard et al. [60]

Only two studies referred to family support in relation to genetic testing [61, 65]. Ford et al. [65] reported that some African American women felt they lacked family support to attend genetic counselling for cancer risk due to the potential negative impact of finding out they were high risk. Sussner et al. [61] reported that Hispanic participants felt family support would motivate them to attend genetic counselling. Both groups acknowledged that the decision was ultimately theirs; therefore, a lack of family support might not prevent individuals from having genetic counselling or testing.

“[Family] wouldn’t keep me from going. If I wanted to go, I would go”

African American female, Ford et al. [65]

A further issue specific to some Chinese Australians was their understanding or definition of ‘close relatives’ [62, 64]. These studies highlighted that, due to the importance placed on the paternal line, maternal family members might not always be considered ‘close relatives.’ Furthermore, when female relatives previously considered close relatives marry into other families, they may no longer be considered as such. Some indicated that relatives would be considered ‘close’ depending on how much they interacted with them rather than by bloodline [64]. These issues could lead to omissions in the assessment of cancer family history, resulting in a less accurate perception of risk.

Service provision and access

Several practical issues were highlighted in relation to uptake of cancer genetic testing. Ease of access to services would motivate attendance for genetic testing [60]. This could be achieved by providing services in local communities and during afternoons or weekends [35]. Physician recommendation was also an important factor in accessing services. Participants in four studies including African Americans, Hispanics, and Chinese Australians indicated that physician recommendation or referral would be a motivator to testing [35, 61, 64, 67], whilst needing yet not receiving a primary care referral would be a barrier [60, 61, 65, 67].

“The doctor mentioned it during my last visit but he didn’t do anything about it so I didn’t do anything.”

Hispanic female, Vadaparampil et al. [67]

As the majority of the qualitative studies took place in the US, cost and insurance were often discussed [35, 52, 60, 61, 63, 65,66,67]. Participants were unsure whether insurance would cover the costs of testing [67] and were unwilling or unable to pay themselves if testing was expensive or not covered by their insurance [35]. Both African Americans [65] and Hispanics voiced concerns that the cost of testing would be a particular barrier within their ethnic group due to low wages and not having health insurance [66]. Some African American participants who were affected by cancer indicated that genetic testing was too important not to have due to financial cost [60].

“I think if I had to incur the fees myself, I wouldn’t think of going…I can’t even imagine having to pay out of my pocket for tests.”

African American female, Ford et al. [65]

Language was identified as a barrier to using genetic services by Hispanics in two studies [61, 66]. Participants were concerned that poor communication, due also to physicians’ use of complex medical language, could have been a reason for their lack of a referral. However, some indicated that the use of a translator, including family members, had been helpful [61].

“But if you are let’s say Spanish and you don’t know the terminology or you don’t know, they (the doctors) think the person is ignorant. That’s not the case because just because you have a language barrier does not make you ignorant.”

Hispanic female, Sussner et al. [61]

Quality assessment

All studies scored quite highly in the quality assessment, receiving scores of 0.75 or above (range 0.75–1.0, see Tables 1 and 2). [Additional file 3 presents the included studies in order of quality with comments on where the study failed to meet the quality criteria.] The quantitative studies scored well for sufficiently describing the study objective, design, method of subject selection, and sample characteristics. Where issues did arise, these were mainly due to shortcomings in analytic methods, for example failing to report sufficient estimates of variance, and having missing data that was not sufficiently acknowledged. Six of the included quantitative studies involved pilot research [36, 38, 46,47,48, 58]; however, this did not necessarily effect the study quality score, for example if it was stated that the analyses were exploratory the criteria of needing to have controlled for confounding was not applicable. The qualitative studies scored highly for sufficiently describing the study objective, design and context. However, none reflected on how the personal characteristics of the researchers may have impacted upon the analysis and results.

Discussion

The current review supports and adds to the findings of previous work by Allford et al. [22], particularly due to the inclusion of several studies with Hispanic participants. The results highlight that only a small proportion of African American, Hispanic, and Asian ethnic minority groups are aware and knowledgeable about genetic testing for cancer susceptibility, and whilst attitudes are quite positive, concerns and negative perceptions exist. Practical issues are also highlighted as potential barriers to obtaining genetic counselling or testing.

Awareness of genetic testing for cancer risk varied across the reviewed studies; however, as recently as 2014, less than 30% of a general population sample of African Americans and Hispanics were aware [30]. The review also found some evidence that more White Americans are aware of genetic testing than Asian American, African American, and Hispanics, and this is further supported by research which did not primarily aim to investigate ethnic minority groups [68, 69]. Importantly, overall awareness of genetic testing for cancer risk was low across all ethnic groups, including White participants, highlighting that within the general population it is not a well-known health service [29, 30, 32].

Ethnic minority groups’ knowledge of genetic risk of cancer also varied across the studies reviewed, indicating low to moderate levels of knowledge. Among samples of participants at high risk for cancer, often less than 50% of knowledge questions were answered correctly. Although knowledge about cancer genetics may not relate to intentions to test, individuals who lack understanding about the hereditary nature of cancer (e.g. that BRCA gene mutations can be passed on by male as well as female relatives) may not pursue genetic testing that is relevant to them. Low awareness and knowledge was also highlighted in qualitative research as a barrier to attending genetic counselling or undergoing genetic testing, and participants suggested a need for awareness and educational interventions especially emphasising the importance of family history of cancer. Qualitative studies also identified several misconceptions about cancer that could deter patients from attending cancer genetic services. However, it is difficult to make generalisations based on the results from qualitative research which may only represent the views of a few individuals. Furthermore, these misconceptions do not appear to be unique to those from ethnic minority groups. For example, Ford et al. [65] report that White women who did not attend genetic counselling discussed the belief that talking about breast cancer could increase their risk; however, this misconception does not appear to have been referred to by African American women in the study. A study of White and Hispanic women found that both groups held misconceptions, including that consuming sugar substitutes and bruising from being hit can cause cancer; but such beliefs were found to be significantly more prevalent in Hispanic women [70]. Similarly, in a more recent UK study, whilst both White and South Asian participants believed that stress causes cancer, significantly more South Asians held this belief and a small minority (4.3%) also believed that cancer is contagious, a misconception that no White participants held [71].

Personal health benefits and the ability to provide information about cancer risk to the family were recognised as important benefits of genetic susceptibility testing. Family support was also discussed as a potential motivator to testing for some Hispanics, suggesting that interventions encouraging Hispanics to attend cancer genetic services could benefit from involving family. Finally, easy access to genetic services is important to facilitate uptake of genetic counselling/testing, and several qualitative studies found that a physician recommendation was a motivator for testing. Physician education on the hereditary basis of some cancers and the importance of referring people with a family history of cancer for genetic counselling is also important to ensure thorough personal risk assessment and that all patients who could benefit from testing are offered this.

Several negative attitudes and perceptions that might influence uptake of genetic susceptibility testing were found to exist among ethnic minority groups, including reluctance to talk about cancer amongst family, concerns about stigma, and concerns about the emotional reaction of undergoing genetic testing and receiving a high risk result. Whilst cancer stigma is not unique to ethnic minorities [72], it is unclear to what extent such perceived stigma and secrecy varies across different ethnic groups. Research has also found that cancer stigma varies in magnitude depending on the type of cancer [73]. As cancer stigma not only has negative consequences for patients’ psychological well-being, and can also discourage individuals from seeking help from healthcare services [74], it seems important that efforts are made to reduce stigma to encourage individuals to attend cancer genetic services.

Other perceptions and issues identified in this review appear to be more specific to certain groups. For example, perceptions of ‘close relatives’ among Chinese Australian communities could hinder risk assessment based on descriptions of family history of cancer, and Hispanic women’s culture of prioritising family over their own health could influence their behaviours relating to genetic testing and cancer risk. These various attitudes and perceptions highlight the importance of identifying the barriers and issues that are specific to different ethnic groups and the need to tailor interventions to address them.

It is particularly important to recognise that historical experiences of ethnic minority groups in different countries may result in varied attitudes towards healthcare and services such as genetic testing. There is well documented mistrust of medical research and the healthcare system among some African Americans, influenced, for example, by the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in which African American males with Syphilis were misled by researchers and refused treatment in order to study the progression of the illness [75]. Practical issues, including cost and the need for health insurance to receive testing, and concerns about insurance discrimination as a result of testing are also more relevant to some American ethnic minorities. The Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act (GINA) was signed into US law in 2008 making it illegal for health insurers and employers to discriminate against individuals on the basis of genetic information and prohibiting insurers from requiring a person to have testing or to provide genetic information. However, the act is limited as it does not cover disability, long-term care, or life insurance. Furthermore, two surveys carried out in 2009/2010 in the US, one with women at increased risk of hereditary breast/ovarian cancer [76] and one with family physicians [77], found that over half had not been aware of GINA before taking part in the survey. Considering the lack of awareness of GINA, even amongst those that might be expected to have an interest in it, and due to the limitations of the act, it is perhaps unsurprising that concerns of discrimination by insurers continues to be cited as a limitation or barrier to genetic testing in the US. In addition, several of the studies included in this review were conducted before GINA was brought into law.

Genetic testing may identify a gene change whose association with disease is not known, a ‘variant of unknown significance’ (VUS). Unlike a pathogenic high risk gene change, the association between a VUS and increased risk of cancer is unclear, leading to issues for providers (counselling, risk management and preventative care) [78] and patients (confusion, psychological impact). It has previously been estimated that approximately 10% of Caucasians undergoing BRCA genetic testing receive a VUS result [79], with a much higher proportion in Hispanics (9–23%) and African Americans (16–24%) [80,81,82]. Different prevalence rates of VUS according to ethnic group lead to differences in the ease of interpretation of results between groups. That public databases of US gene testing will have far fewer non-Whites on them than Whites contributes to the problem of interpretation. Many VUS in non-Whites will be poorly characterised compared with Whites simply because less data is available on them. The greater likelihood of receiving an uninformative VUS result in African ethnic groups might potentially contribute to a lack of understanding about genetic testing or its perceived benefits, but our review provides no evidence to support this hypothesis.

The majority of the reviewed studies were conducted in the US which limits their generalisability to other countries, particularly in relation to levels of awareness and knowledge. Nevertheless, lack of awareness, the taboo of discussing cancer, and language difficulties, have also been reported in a UK genetics service evaluation [83] and a Genetics Alliance UK report involving interviews with individuals from ethnic minorities [84]. The evaluation of a UK pilot genetic service within a culturally diverse society by Atkin et al. [83] reports that poor communication was a barrier for both White and South Asian patients; however, communication issues were most difficult for those whose first language was not English and language support was not always viewed positively. Furthermore, some female patients reported that discussing breast cancer with male practitioners was embarrassing and even felt shameful. The article highlights the benefit of employing multilingual, culturally sensitive workers within the clinic [83]. In other research, cancer fatalism has been found to be higher amongst ethnic minority women in the UK than White women, whilst cancer fear appears to vary by ethnic group [85]. Further research into the attitudes and perceptions of ethnic minority groups in the UK and other European countries is needed in order to gain a better understanding of specific cultural barriers to cancer susceptibility testing.

The review has a number of limitations including the omission of intervention studies aiming to increase participant knowledge of cancer genetics from which we may have been able to extract baseline data. We did not include unpublished literature and our experience of using the quality assessment tool, specifically chosen for its ability to assess both qualitative and quantitative studies, indicated that it lacked a finer discriminatory capacity. The heterogeneous nature of the measures of awareness, knowledge, and attitudes used across various ethnic groups and different cancer types in the quantitative studies, made a meta-analysis impossible and interpretation of results difficult. Furthermore, the majority of included studies measuring knowledge and attitudes included only at risk patients or those already with a cancer diagnosis; therefore, results may not represent the knowledge or attitudes of the general population of ethnic minorities. Whilst still in the early stages of conception, due to an increasing understanding of cancer genetics and decreases in the cost of genetic testing, population based risk stratified interventions for cancer including genetic susceptibility testing are likely to be introduced in the future. Such interventions would provide people with information on their risk of cancer, and screening or treatment would be recommended based on their estimated level of risk. Before such interventions become a reality it is necessary to gain an understanding of the attitudes of the wider population, including those who are currently underserved such as ethnic minority groups. Meisel et al. [86] found positive attitudes towards population-based genetic testing and risk stratified screening for ovarian cancer amongst a sample of women from the UK general population. However, just 34% of the sample interviewed were non-White participants and cultural/ethnic differences in attitudes and perceptions were not discussed in detail.

Conclusions

Widening public participation amongst ethnic minority groups in future cancer risk prediction programmes may be enabled by culturally sensitive knowledge and awareness raising interventions that decrease the stigma and taboo of cancer. For this, further international research is needed to provide clearer information of ethnic minorities’ attitudes, and information and support needs so that cancer risk prediction programmes are inclusive and effective in the prevention and early detection of cancer.

Abbreviations

- GINA:

-

Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- US:

-

United States

- VUS:

-

Variant of unknown significance

References

Garber JE, Offit K. Hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(2):276–92.

Jasperson KW, Tuohy TM, Neklason DW, Burt RW. Hereditary and familial colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(6):2044–58.

McPhearson K, Steel C, Dixon J. Breast cancer-epidemiology, risk factors and genetics. Br Med J. 2000;321:624–8.

Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, Liu Q, Cochran C, Bennett LM, Ding W. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266(5182):66–71.

Edwards SM, Kote-Jarai Z, Meitz J, Hamoudi R, Hope Q, Osin P, Jackson R, Southgate C, Singh R, Falconer A, et al. Two percent of men with early-onset prostate cancer harbor germline mutations in the BRCA2 gene. Am J Human Genet. 2003;72(1):1–12.

Axilbund JE, Peshkin BN. Hereditary cancer risk. US: Springer; 2010.

Etchegary H. Public attitudes toward genetic risk testing and its role in healthcare. Personalized Med. 2014;11(5):509–22.

Henneman L, Vermeulen E, van El CG, Claassen L, Timmermans DR, Cornel MC. Public attitudes towards genetic testing revisited: comparing opinions between 2002 and 2010. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(8):793–9.

Haga SB, Barry WT, Mills R, Ginsburg GS, Svetkey L, Sullivan J, Willard HF. Public knowledge of and attitudes toward genetics and genetic testing. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2013;17(4):327–35.

Jack RH, Davies EA, Møller H. Breast cancer incidence, stage, treatment and survival in ethnic groups in South East England. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(3):545–50.

Odedina FT, Akinremi TO, Chinegwundoh F, Roberts R, Yu D, Reams RR, Freedman ML, Rivers B, Green BL, Kumar N. Prostate cancer disparities in black men of African descent: a comparative literature review of prostate cancer burden among black men in the United States, Caribbean, United Kingdom, and West Africa. Infect Agents Cancer. 2009;4(1):S2.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29.

Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Miller KD, Goding-Sauer A, Pinheiro PS, Martinez-Tyson D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(6):457–80.

Gomez SL, Noone AM, Lichtensztajn DY, Scoppa S, Gibson JT, Liu L, Morris C, Kwong S, Fish K, Wilkens LR, et al. Cancer incidence trends among Asian American populations in the United States, 1990–2008. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2013;105(15):1096–110.

Godard B, Kaariainen H, Kristoffersson U, Tranebjaerg L, Coviello D, Ayme S. Provision of genetic services in Europe: current practices and issues. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11(Suppl 2):S13–48.

Hall MJ, Olopade OI. Disparities in genetic testing: thinking outside the BRCA box. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(14):2197–203.

Hensley Alford S, McBride CM, Reid RJ, Larson EB, Baxevanis AD, Brody LC. Participation in genetic testing research varies by social group. Public Health Genomics. 2011;14(2):85–93.

van Riel E, van Dulmen S, Ausems MGEM. Who is being referred to cancer genetic counseling? Characteristics of counselees and their referral. J Community Genet. 2012;3(4):265–74.

Wonderling D, Hopwood P, Cull A, Douglas F, Watson M, DBurn J, McPherson K. A descriptive study of UK cancer genetics services: an emerging clinical response to the new genetics. Br J Cancer. 2001;85(2):166–70.

Armstrong K, Weber B, Stopfer J, Calzone K, Putt M, Coyne J, Schwartz JS. Early use of clinical BRCA1/2 testing: associations with race and breast cancer risk. Am J Med Genet. 2003;117A(2):154–60.

Levy DE, Byfield SD, Comstock CB, Garber JE, Syngal S, Crown WH, Shields AE. Underutilization of BRCA1/2 testing to guide breast cancer treatment: black and Hispanic women particularly at risk. Genet Med. 2011;13(4):349–55.

Allford A, Qureshi N, Barwell J, Lewis C, Kai J. What hinders minority ethnic access to cancer genetics services and what may help? Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(7):866–74.

Lee SC, Bernhardt BA, Helzlsouer KJ. Utilization of BRCA1/2 genetic testing in the clinical setting: report from a single institution. Cancer. 2002;94(6):1876–85.

Armstrong K, Calzone K, Stopfer J, Fitzgerald G, Coyne J, Weber B. Factors associated with decisions about clinical BRCA1/2 testing. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2000;9(11):1251–4.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45.

Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. 2004:1-22.

Gammon AD, Rothwell E, Simmons R, Lowery JT, Ballinger L, Hill DA, Boucher KM, Kinney AY. Awareness and preferences regarding BRCA1/2 genetic counseling and testing among Latinas and non-Latina white women at increased risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Genet Couns. 2011;20(6):625–38.

Heck JE, Franco R, Jurkowski JM, Sheinfeld Gorin S. Awareness of genetic testing for cancer among United States Hispanics: the role of acculturation. J Community Genet. 2008;11(1):36–42.

Honda K. Who gets the information about genetic testing for cancer risk? The role of race/ethnicity, immigration status, and primary care clinicians. Clin Genet. 2003;64:131–6.

Huang H, Apouey B, Andrews J. Racial and ethnic disparities in awareness of cancer genetic testing among online users: internet use, health knowledge, and socio-demographic correlates. J Consum Health Internet. 2014;18(1):15–30.

Kaplan CP, Haas JS, Perez-Stable EJ, Gregorich SE, Somkin C, Des Jarlais G, Kerlikowske K. Breast cancer risk reduction options: awareness, discussion, and use among women from four ethnic groups. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15(1):162–6.

Pagan JA, Su D, Li L, Armstrong K, Asch DA. Racial and ethnic disparities in awareness of genetic testing for cancer risk. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):524–30.

Peters N, Rose A, Armstrong K. The association between race and attitudes about predictive genetic testing. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2004;13(3):361–5.

Vadaparampil ST, Wideroff L, Breen N, Trapido E. The impact of acculturation on awareness of genetic testing for increased cancer risk among Hispanics in the year 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15(4):618–23.

Adams I, Christopher J, Williams KP, Sheppard VB. What black women know and want to know about counseling and testing for BRCA1/2. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(2):344–52.

Ramirez AG, Aparicio-Ting FE, de Majors SS, Miller AR. Interest, awareness, and perceptions of genetic testing among Hispanic family members of breast cancer survivors. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(2):398–403.

Satia JA, McRitchie S, Kupper LL, Halbert CH. Genetic testing for colon cancer among African-Americans in North Carolina. Prev Med. 2006;42(1):51–9.

Sussner KM, Jandorf L, Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB. Interest and beliefs about BRCA genetic counseling among at-risk Latinas in new York City. J Genet Couns. 2010;19(3):255–68.

Sussner KM, Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Redd WH, Jandorf L. Acculturation and familiarity with, attitudes towards and beliefs about genetic testing for cancer risk within Latinas in East Harlem, new York City. J Genet Couns. 2009;18(1):60–71.

Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Jandorf L, Redd W. Perceived disadvantages and concerns about abuses of genetic testing for cancer risk: differences across African American, Latina and Caucasian women. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51(3):217–27.

Sussner KM, Jandorf L, Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB. Barriers and facilitators to BRCA genetic counseling among at-risk Latinas in new York City. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(7):1594–604.

Donovan KA, Tucker DC. Knowledge about genetic risk for breast cancer and perceptions of genetic testing in a sociodemographically diverse sample. J Behav Med. 2000;23(3):15–36.

Kinney AY, Croyle RT, Dudley WN, Bailey CA, Pelias MK, Neuhausen SL. Knowledge, attitudes, and interest in breast-ovarian cancer gene testing: a survey of a large African-American kindred with a BRCA1 mutation. Prev Med. 2001;33(6):543–51.

Kinney AY, Simonsen SE, Baty BJ, Mandal D, Neuhausen SL, Seggar K, Holubkov R, Smith K. Acceptance of genetic testing for hereditary breast ovarian cancer among study enrollees from an African American kindred. Am J Med Genet . 2006;140(8):813–26.

Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Duteau-Buck C, Guevarra J, Dana H, Bovbjerg DC, Richmond-Avellaneda C, Amarel D, Godfrey D, Brown K, Offit K. Psychosocial predictors of BRCA counseling and testing decisions among urban African-American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2002;11:1579–85.

Weinrich S, Vijayakumar S, Powell IJ, Priest J, Hamner CA, McCloud L, Pettaway C. Knowledge of hereditary prostate cancer among high-risk African American men. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(4):845.

Vadaparampil ST, Quinn GP, Dutil J, Puig M, Malo TL, McIntyre J, Perales R, August EM, Closser Z. A pilot study of knowledge and interest of genetic counseling and testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome among Puerto Rican women. J Community Genet. 2011;2(4):211–21.

Vadaparampil ST, Quinn GP, Small BJ, McIntyre J, Loi CA, Closser Z, Gwede CK. A pilot study of hereditary breast and ovarian knowledge among a multiethnic group of Hispanic women with a personal or family history of cancer. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2010;14(1):99–106.

Edwards TA, Thompson HS, Kwate NO, Brown K, McGovern MM, Forman A, Kapil-Pair N, Jandorf L, Bovbjerg DH, Valdimarsdottir HB. Association between temporal orientation and attitudes about BRCA1/2 testing among women of African descent with family histories of breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72(2):276–82.

Kessler L, Collier A, Brewster K, Smith C, Weathers B, Wileyto EP, Halbert CH. Attitudes about genetic testing and genetic testing intentions in African American women at increased risk for hereditary breast cancer. Genet Med. 2005;7(4):230–8.

Sussner KM, Edwards TA, Thompson HS, Jandorf L, Kwate NO, Forman A, Brown K, Kapil-Pair N, Bovbjerg DH, Schwartz MD, et al. Ethnic, racial and cultural identity and perceived benefits and barriers related to genetic testing for breast cancer among at-risk women of African descent in new York City. Public Health Genomics. 2011;14(6):356–70.

Matthews AK, Cummings S, Thompson S, Wohl V, List M, Olopade OI. Genetic testing of African Americans for susceptibility to inherited cancers: use of focus groups to determine factors contributing to participation. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2000;18(2):1–19.

Armstrong K, Micco E, Carney A, Stopfer J, Putt M. Racial differences in the use of BRCA1/2 testing among women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;293(14):1729–36.

Myers RE, Hyslop T, Jennings-Dozier K, Wolf TA, Burgh DY, Diehl JA, Caryn Lerman C, Chodak GW. Intention to be tested for prostate cancer risk among African-American men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2000;9:1323–8.

Weinrich S, Royal C, Pettaway CA, Dunston G, Faison-Smith L, Priest JH, Roberson-Smith P, Frost J, Jenkins J, Brooks KA, et al. Interest in genetic prostate cancer susceptibility testing among African American men. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25(1):28–34.

Sussner KM, Thompson HS, Jandorf L, Edwards TA, Forman A, Brown K, Kapil-Pair N, Bovbjerg DH, Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB. The influence of acculturation and breast cancer-specific distress on perceived barriers to genetic testing for breast cancer among women of African descent. Psycho Oncol. 2009;18(9):945–55.

Armstrong K, Putt M, Halbert CH, Grande D, Schwartz JS, Liao K, Marcus N, Demeter MB, Shea J. The influence of health care policies and health care system distrust on willingness to undergo genetic testing. Med Care. 2012;50(5):381–7.

McBride CM, Lipkus IM, Jolly D, Lyna P. Interest in testing for genetic susceptibility to lung cancer among black college students “at risk” of becoming cigarette smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2005;14(12):2978–81.

Hughes C, Fasaye G-A, LaSalle VH, Finch C. Sociocultural influences on participation in genetic risk assessment and testing among African American women. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51(2):107–14.

Sheppard VB, Graves KD, Christopher J, Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Talley C, Williams KP. African American women's limited knowledge and experiences with genetic counseling for hereditary breast cancer. J Genet Couns. 2014;23(3):311–22.

Sussner KM, Edwards T, Villagra C, Rodriguez MC, Thompson HS, Jandorf L, Valdimarsdottir HB. BRCA genetic counseling among at-risk Latinas in new York City: new beliefs shape new generation. J Genet Couns. 2015;24(1):134–48.

Eisenbruch M, Yeo SS, Meiser B, Goldstein D, Tucker K, Barlow-Stewart K. Optimising clinical practice in cancer genetics with cultural competence: lessons to be learned from ethnographic research with Chinese-Australians. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(2):235–48.

Glenn BA, Chawla N, Bastani R. Barriers to genetic testing for breast cancer risk among ethnic minority women: an exploratory study. Ethn Dis. 2012;22(3):267–73.

Barlow-Stewart K, Yeo SS, Meiser B, Goldstein D, Tucker K, Eisenbruch M. Toward cultural competence in cancer genetic counseling and genetics education: lessons learned from Chinese-Australians. Genet Med. 2006;8(8):24–32.

Ford ME, Alford SH, Britton D, McClary B, Gordon HS. Factors influencing perceptions of breast cancer genetic counseling among women in an urban health care system. J Genet Couns. 2007;16(6):735–53.

Kinney AY, Gammon A, Coxworth J, Simonsen SE, Arce-Laretta M. Exploring attitudes, beliefs, and communication preferences of Latino community members regarding BRCA1/2 mutation testing and preventive strategies. Genet Med. 2010;12(2):105–15.

Vadaparampil ST, McIntyre J, Quinn GP. Awareness, perceptions, and provider recommendation related to genetic testing for hereditary breast cancer risk among at-risk Hispanic women: similarities and variations by sub-ethnicity. J Genet Couns. 2010;19(6):618–29.

Lacour RA, Daniels MS, Westin SN, Meyer LA, Burke CC, Burns KA, Kurian S, Webb NF, Pustilnik TB, Lu KH. What women with ovarian cancer think and know about genetic testing. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111(1):132–6.

Mai PL, Vadaparampil ST, Breen N, McNeel TS, Wideroff L, Graubard BI. Awareness of cancer susceptibility genetic testing: the 2000, 2005, and 2010 National Health Interview Surveys. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(5):440–8.

Pérez-Stable EJ, Sabogal F, Otero-Sabogal R, Hiatt RA, McPhee SJ. Misconceptions about cancer among Latinos and Anglos. JAMA. 1992;268(22):3219–23.

Lord K, Mitchell AJ, Ibrahim K, Kumar S, Rudd N, Symonds P. The beliefs and knowledge of patients newly diagnosed with cancer in a UK ethnically diverse population. Clin Oncol. 2012;24(1):4–12.

Daher M. Cultural beliefs and values in cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 3):66–9.

Marlow LAV, Waller J, Wardle J. Does lung cancer attract greater stigma than other cancer types? Lung Cancer. 2015;88(1):104–7.

Fujisawa D, Hagiwara N. Cancer stigma and its health consequences. Current Breast Cancer Reports. 2015;7(3):143–50.

Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(11):1773–8.

Allain DC, Friedman S, Senter L. Consumer awareness and attitudes about insurance discrimination post enactment of the genetic information nondiscrimination act. Familial Cancer. 2012;11:637–44.

Laedtke AL, O’Neill SM, Rubinstein WS, Vogel KJ. Family physicians’ awareness and knowledge of the genetic information non-discrimination act (GINA). J Genet Couns. 2012;21:345–52.

Eccles D, Mitchell G, Monteiro ANA, Schmutzler R, Couch FJ, Spurdle AB, Gómez-García EB, Driessen R, Lindor NM, Blok MJ, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing–pitfalls and recommendations for managing variants of uncertain clinical significance. Ann Oncol. 2015;10:2057–65. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdv278.

Frank TS, Critchfield GC. Hereditary risk of women’s cancers. Best Practice Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;16(5):703–13.

Kurian AW. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations across race and ethnicity: distribution and clinical implications. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;22(1):72–8.

Nanda R, Schumm LP, Cummings S, Fackenthal JD, Sveen L, Ademuyiwa F, Cobleigh M, Esserman L, Lindor NM, Neuhausen SL, et al. Genetic testing in an ethnically diverse cohort of high-risk women a comparative analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in American families of European and African ancestry. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294(15):1925–33.

Weitzel JN, Lagos V, Blazer KR, Nelson R, Ricker C, Herzog J, McGuire C, Neuhausen S. Prevalence of BRCA mutations and founder effect in high-risk Hispanic families. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2005;14(7):1666–71.

Atkin K, Ali N, Chu CE. The politics of difference? Providing a cancer genetics service in a culturally and linguistically diverse society. Divers Health Care. 2009;6(3):149–57.

Genetic Alliance UK. Identifying family risk of cancer: Why is this much more difficult for ethnic minority communities and what would help. 2012.

Vrinten C, Wardle J, Marlow LA. Cancer fear and fatalism among ethnic minority women in the United Kingdom. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(5):597–604.

Meisel SF, Side L, Fraser L, Gessler S, Wardle J, Lanceley A. Population-based, risk-stratified genetic testing for ovarian cancer risk: a focus group study. Public Health Genomics. 2013;16:184–91.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out at UCLH/UCL within the Cancer Theme of the NIHR UCLH/UCL Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre supported by the UK Department of Health for the PROMISE study team.

Funding

Completion of this project was funded by the Eve Appeal and Cancer Research (grant code: UKC1005/A12677). The funders had no role in the study design; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the report for publicationThis work was supported by.

Availability of data and materials

The data is included in the manuscript and tables.

Authors’ contribution

AL and KH designed the study. LF, JW and SS contributed to the design of the study. LS and SG provided design implementation support. KH conducted the literature search and carried out study selection with BR, MF and AL. KH and MF extracted the data and conducted the quality assessment of studies. KH drafted the manuscript which all authors critically reviewed and approved. All listed authors meet the criteria for authorship and no individual meeting these criteria has been omitted.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Review search terms. Full search terms for PsycInfo, CINAHL, Embase and MEDLINE used to find studies for the review. (DOCX 18 kb)

Additional file 2:

Study specific measures: Awareness, knowledge, and attitudes. The table presents descriptions of the main measures used to investigate awareness, knowledge and attitudes in relation to genetic counselling/testing. (DOCX 17 kb)

Additional file 3:

Rank order of included studies based on quality assessment. The table presents the quality assessments for each study and comments on why studies were marked down. (DOCX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hann, K.E.J., Freeman, M., Fraser, L. et al. Awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes towards genetic testing for cancer risk among ethnic minority groups: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 17, 503 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4375-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4375-8