Abstract

Background

Real life implementation studies performed in different settings and populations proved that lifestyle interventions in prevention of type 2 diabetes can be effective. However, little is known about long term results of these translational studies. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the maintenance of diabetes type 2 risk factor reduction achieved 1 year after intervention and during 3 year follow-up in primary health care setting in Poland.

Methods

Study participants (n = 262), middle aged, slightly obese, with increased type 2 diabetes risk ((age 55.5 (SD = 11.3), BMI 32 (SD = 4.8), Finnish Diabetes Risk Score FINDRISC 18.4 (SD = 2.9)) but no diabetes at baseline, were invited for 1 individual and 10 group lifestyle counselling sessions as well as received 6 motivational phone calls and 2 letters followed by organized physical activity sessions combined with counselling to increase physical activity.

Measurements were performed at baseline and then repeated 1 and 3 years after the initiation of the intervention.

Results

One hundred five participants completed all 3 examinations (baseline age 56.6 (SD = 10.7)), BMI 31.1 (SD = 4.9)), FINDRISC 18.57 (SD = 3.09)). Males comprised 13% of the group, 10% of the patients presented impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and 14% impaired glucose tolerance (IGT). Mean weight of participants decreased by 2.27 kg (SD = 5.25) after 1 year (p = <0.001). After 3 years a weight gain by 1.13 kg (SD = 4.6) (p = 0.04) was observed. In comparison with baseline however, the mean total weight loss at the end of the study was maintained by 1.14 kg (SD = 5.8) (ns). Diabetes risk (FINDRISC) declined after one year by 2.8 (SD = 3.6) (p = 0.001) and the decrease by 2.26 (SD = 4.27) was maintained after 3 years (p = 0.001). Body mass reduction by >5% was achieved after 1 and 3 years by 27 and 19% of the participants, respectively.

Repeated measures analysis revealed significant changes observed from baseline to year 1 and year 3 in: weight (p = 0.048), BMI (p = 0.001), total cholesterol (p = 0.013), TG (p = 0.061), fasting glucose level (p = 0.037) and FINDRISC (p = 0.001) parameters. The conversion rate to diabetes was 2% after 1 year and 7% after 3 years.

Conclusions

Type 2 diabetes prevention in real life primary health care setting through lifestyle intervention delivered by trained nurses leads to modest weight reduction, favorable cardiovascular risk factors changes and decrease of diabetes risk. These beneficial outcomes can be maintained at a 3-year follow-up.

Trial registration

ISRCTN, ID ISRCTN96692060, registered 03.08.2016 retrospectively

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Randomized control trials (RCT) performed in different populations have demonstrated up to 60% reduction in type 2 diabetes incidence through lifestyle intervention which leads to dietary and physical activity changes [1,2,3,4]. Furthermore, the effect of interventions in RCT setting has been shown to continue up to 20 years with 34–43% diabetes risk reduction [5,6,7,8]. Typically, the interventions in these clinical efficacy trials have been intensive and thus costly. Therefore, EU initiated and sponsored the DE-PLAN project (Diabetes in Europe: Prevention Using Lifestyle, Physical Activity and Nutritional Intervention) as a real life implementation study in 17 countries in Europe [9]. The aim of the project was to assess the reach of the programs, adoption and implementation in diverse real life settings, but also to create a network of trained and experienced professionals to continue diabetes prevention across Europe [9]. Indeed, real life implementation studies conducted in different settings and populations proved that less intensive, lower budget lifestyle interventions can be effective [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. However, little is known about the long term results of these translational studies. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the maintenance of risk factor reduction during 3 year follow-up in real life, primary health care setting in Poland.

Methods

Design

The intervention conducted in the DE-PLAN project was based on the principles of the Diabetes Prevention Study [1, 9]. Given that the efficacy of lifestyle modification treatments has been well established by earlier diabetes prevention trials, the need for an additional randomized controlled trial study design in the current program was regarded as unnecessary and unethical. A detailed description of the program performed in Poland, including the inclusion criteria, the characteristic of participants, methods, the intervention and one-year results has been published previously [10].

Participants

The study was performed in 9 independent primary health care General Practitioners (GP) practices in Krakow. The study group consisted of everyday patients, city inhabitants, aged over 25. The inclusion criterion was high diabetes risk assessed with the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC) > 14) (33% chance of developing diabetes within 10 years) [22], the exclusion criteria was either known diabetes or oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) screening diabetes as well as known chronic disease which could affect the results of the study. Advertisements were placed alongside self-screening questionnaires in the GPs’ waiting rooms. In addition, patients with known risk factors were directly approached by nursing and medical staff. Out of 800 leaflets with the FRS questionnaire distributed in co-operating practices, 566 were completed. 368 respondents scored FRS >14; 275 agreed to undergo OGTT examination and subsequently 262 (with all measurements done) were invited to participate in the intervention. 175 participants completed the intervention and the final examination after 1 year and 113 completed follow-up examination after 3 years. 9 people (8 with complete measurements) who participated in the 3 year follow-up did not participate in 1 year examination. 105 patients took part in all 3 measurements (completers) while 79 did not participate in the 1 year and 3 year follow-up examinations (non-completers). The most commonly declared non-participation reason was shortage of time and inability to continue “time-consuming program”.

Intervention

Lifestyle intervention implemented the principles of the Diabetes Prevention Study [1] and was based on reinforced behavior modification focusing on five lifestyle goals: loss of initial weight, reduced intake of total and saturated fats, increased consumption of fruit, vegetables and fiber and increased physical activity [1, 9, 10]. The intervention curriculum was created on the basis of written materials containing basic information about diabetes, diabetes prevention, diet, diet examples booklet and information about physical activity.

Well-trained nurses (2 nurses per one center), certified in diabetes prevention, delivered 10-month intervention. The initial intensive phase of intervention (4 months) consisted of 1 individual session followed by 10 group sessions (10–14 people), focusing on diet and physical activity changes. During each session printed educational materials related to the topic of the session were distributed. Social support was emphasized by the group setting and participants were also encouraged to invite their own social environment to lifestyle changes. A spouse or other family member could also participate in the sessions. After the initial 4 weeks of the intervention patients could take part in physical activity sessions twice a week (once a week – aqua aerobics; once a week – gymnastics or football). The following maintenance phase of the intervention (month: 4–10) following the intensive phase consisted of six motivational telephone sessions and two motivational letters received by the participants [1, 9, 10]. There were no other post-intervention contacts with the participants except measurements in year 1 and 3.

Measurements

Patients were examined at baseline as well as after 12 and 36 months of the study. The examination procedure included: questionnaires (FINDRISC, baseline, clinical and lifestyle and quality of life) and biochemical tests including: fasting and 120’OGTT glucose, serum triglycerides, HDL and total cholesterol. Impaired Fasting Glucose (IFG) was defined as fasting plasma glucose concentration of 6.1 to 7.0 mmol/l. Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT) was defined as glucose plasma concentration of 7.80 to 11.0 mmol/l after oral administration of 75 g of glucose (OGTT), diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined as fasting glucose concentration of more than 7.0 mmol/l [23]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (in light indoor clothes, kg) divided by height squared (m2), waist circumference was measured midway between the lowest rib and iliac crest, diastolic and systolic blood pressure were taken while sitting after 10 min rest.

Ethics

This study followed the Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration. The study protocol was approved by the Jagiellonian University Ethics Committee.

Statistical analyses

The descriptive analyses are given in percentages (for categorical variables) and means with standard deviations (for continuous variables). The normality of distribution was assessed by skewness and kurtosis analysis. Differences between groups were assessed using chi-square and t-test for dependent groups (respectively for the type of data). For comparison of the 3 measurements the repeated measures ANOVA and main effect comparisons (pairwise t-tests) with Bonferroni correction was performed. All analyses were competed with SPSS v.20. P-value of < 0.05 was considered as the level of statistical significance.

Results

105 middle aged participants (age 56.6 (SD = 10.7)), slightly obese (BMI 31.11 (SD = 4.9)), with high risk of developing diabetes (FRS 18.57 (SD = 3.09) completed all 3 examinations.

Baseline characteristics of completers vs non-completers

Baseline characteristics of completers (n = 105) vs non-completers (n = 79) is given in Table 1. At baseline, non-completers in comparison with completers were heavier (89.7 vs 82.85 kg), had higher BMI (32.66 vs 31.11 kg/m2) and waist circumference 101.23 vs 96.67 cm) (p for all <0.05). Additionally non-completers had higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure (134.8 vs 130.7 (p = 0.051) and 83.48 vs 80.8 (p = 0.060), respectively) as well as higher fasting and OGTT glucose level (5.55 vs 5.22 (p = 0.01) and 7.1 vs 5.77 mmol/l (p < 0.001), respectively. Completers had normal glucose tolerance (NGT) more often than non-completers (76% vs 63% (p = 0.04)). 13% of the completers and 31.9% of the non-completers were men (p = 0.004). No other biochemical, anthropometric and sociodemographic differences between completers and non-completers were found.

Clinical outcomes for completers

Clinical and metabolic characteristics of completers from baseline to year 1 and 3 is given in Table 2. Using repeated measures statistical analysis, we found significant changes in the following parameters: weight (p = 0.048), BMI (p = 0.001), glucose level (p = 0.037), total cholesterol (p=0.013), TG (p= 0.061) and FINDRISC (p = 0.001) Mean weight decreased by 2.27 kg (SD = 5.24) after one year (p = 0.001). After 3 years a weight gain of 1.13 kg (SD = 4.6) (p = 0.0405) was noted. Nonetheless, the mean weight was still lower compared to baseline by 1.14 kg (SD = 5.8) (ns).

The same trend of changes after 1 and 3 years was observed for BMI (p < 0.001 for both time points). Total cholesterol level diminished after one year by 0.26 mmol/l (SD = 1.16) (p = 0.065) and by 0.29 mmol/l (SD = 1.03) after 3 years (p= 0.016). TG decreased after one year by 0.14 mmol/l (SD = 1.33) (ns) and by 0.23 (SD = 1.22) (ns) after 3 years. FINDRISC went down after one year by 2.8 (SD = 3.6) (p = 0.001) and by 2.26 (SD = 4.27) after 3 years (p = 0.001). We also observed an increase of fasting glucose after one year by 0.17 mmol/l (SD = 0.67) (p = 0.066) and by 1.12 mmol/l (SD = 0.68) (p = 0.067) after 3 years.

At baseline 76% of participants had NGT, 10% IFG and 14% IGT. After 1 year of the study 73% of patients had NGT, 2% DM, 5% IFG and 20% IGT. After 3 years 74% of participants had NGT, 7% DM, 9% IFG and 11% IGT.

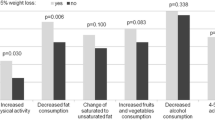

After 1 year 15% of baseline NGT patients converted to IFG or IGT and 1% to DM. After 3 years 19% of baseline NGT patients converted to IFG or IGT and 1% to DM. 10% and 20% of baseline IFG patients converted to DM after 1 and 3 years, respectively. Among baseline IGT participants none developed DM after 1 year but 27% converted to DM after 3 years of the study. 2 people with DM diagnosed after 1 year participated in the 3 year examination ( treated with diet only). They were categorized as DM again. After one year 27% participants lost weight by > 5%, 43% by < 5% and 31% did not change or increase body mass. After 3 years 19% participants maintained lower weight decreased by > 5%, 37% decreased by < 5%, and 44% did not change weight or increased body mass.

Discussion

The results of this study show that type 2 diabetes prevention through lifestyle intervention in a primary health care setting is feasible and effective, and the results can be maintained during long-time observation. The evidence from RCTs confirmed that through lifestyle intervention including dietary modification, weight loss and physical activity, the reduction in type 2 diabetes incidence might be maintained long after the intervention. [5,6,7,8]. While there is evidence from RCTs, there are only a few long-time observations of implementation studies [21, 24]. In our real life implementation study conducted by trained nurses we demonstrated a modest weight reduction, by 2.27 kg, after 1 year of intervention. The change was subtle, however, it was accompanied by a reduction of total blood cholesterol, triglycerides as well as a lowered diabetes risk. Results achieved at one year were further maintained at 3 year follow-up.

Similar results were achieved in The Good Ageing in Lahti Region (GOAL) Lifestyle Implementation trial. This study was also designed for primary health care setting with lifestyle and risk reduction objectives based on the DPS. Similarly, the intervention was conducted by study nurses and consisted of 6 group counselling sessions [14, 21]. Patients were examined in year 1 of the intervention and after 3 years of the follow-up. The results after one year were also modest with the mean body mass reduction of 0.8 (SD = 4.5 kg) followed by modest but significant reduction in waist circumference, fasting glucose and total cholesterol. The 3 year follow-up body weight reduction was 1.0 (SD = 5.6 kg) which is comparable to our results. Furthermore, total cholesterol decrease and triglycerides reduction were also maintained after 3 years.

In our study the conversion rate to diabetes in all participants (baseline IGT, IFG and NGT) reached 2% after 1 year and 7% after 3 years. Data concerning the conversion rate are not easy to compare between different studies as various design, time of observation and risk of intervened people were applied. In the GOAL study, for example, the conversion rate from IGT to type 2 diabetes was 12% at 3 year follow-up while in the DPS study, where all participants had baseline IGT, the conversion rate was 9% in the intervention and 20% in the control group [4, 21]. The lower conversion rate in our study might be explained by lower risk level at baseline. In the DPS all participants had IGT at baseline, while in our study only 10% exhibited IFG and 14% IGT. However, the very low conversion rate to diabetes in our study should be regarded as an evidence of successful short and long term intervention.

In a review focusing on translational lifestyle interventions, Johnson et al. concluded that effectiveness could not be easily demonstrated with clinical parameters, such as blood glucose or T2DM risk [19].

Given the relatively short follow-up time and small sample size, real life prevention studies may have sufficient statistical power to measure change in weight rather than T2DM incidence [19]. Therefore, weight loss in these studies can be regarded as a marker for potential prevention in the long-term [19, 20].

Additionally, the reduction in FINDRISC score in our study, which changed from 18.57 at baseline to 15.76 at year 1 and 16.30 at year 3 can be used as a surrogate marker for diabetes risk reduction.

In the DPP study, weight loss was reported to be the dominant factor in T2DM prevention, with a loss of 5 kg explaining the 55% reduction incidence of T2DM over 3 years follow-up [24]. In the RCTs weight loss was correlated with the intensity of the delivered program. It is important to remember that intervention given in RTCs is typically incomparable to translational studies, which typically provide a less intensive, low budget intervention adapted to local and cultural possibilities. Consequently, as seen also in our study, the achieved weight reduction is usually modest compared with RCTs. Also, the percentage of people who lost > 5% of initial weight was substantially lower in our study than in the DPS or DPP studies (27% after one year and 19% after 3 years of the follow-up). However, modest weight reduction in our study should be regarded as a measure of success. In general population there is a weight increase by 0.5 kg per year, thus even small weight reduction or weight maintenance should be considered important achievements in diabetes prevention [25].

Although in our study there was a weight regain of 1.13 kg after 3 years, the weight decrease by 1.14 kg was still maintained even though the metabolic changes observed after intervention were still present at 3 year follow-up. According to the DPS, body weight during follow-up increased gradually in both groups but a statistically significant difference between the study groups prevailed [6]. Moreover, both metabolic improvements and lifestyle changes continued over time in those who were intervened [6].

In the meta-analysis of 22 real life implementation studies conducted by Dunkley et al. the mean proportion of weight lost (%) at 12 months follow-up was 2.6%. It was concluded that despite the drop-off in intervention effectiveness in translational studies, the modest level of weight loss found in the analysis is still likely to have a clinically meaningful effect on diabetes incidence. The rate of progression to diabetes was calculated 34 per 1000 person-years which suggests that the real world lifestyle intervention studies achieved lower diabetes progression rates in comparison to natural progression rates in high risk individuals [20].

Some limitations of our study need to be discussed. The participants in our study were volunteers, and similarly to many other studies, our study predominantly attracted women, who accounted for 87% of participating in both examinations. Thus, our results might not be generalized in reference to both sexes. In addition, rather modest results obtained in our study might be influenced by female sex domination, whose success in previous diabetes prevention studies was meager when compared to men [26]. It also implies the need for further studies on sex specific mechanism in real life lifestyle interventions. Our study also confirmed that people who participate in epidemiological studies have a healthier profile, are less obese and have better blood pressure and biochemical profiles than non-attenders, therefore the results of the intervention might be less obvious in those baseline healthier people [27]. In our study there were no particular socioeconomic differences between completers and non-completers. However low socioeconomic status could be related to less frequent use of healthcare services despite poorer health status [28]. These observations highlight the need to develop lifestyle interventions further in order to increase participation of males and particularly those who are at high risk [18, 20].

A modified program based on the DE-PLAN sponsored by the local self-government is being continued in Krakow. Methodology, results and experience from the DE-PLAN project were used in the preparation of the European guidelines for the prevention of type 2 diabetes and the toolkit for diabetes prevention in Europe [29, 30]. There are also some other European initiatives on diabetes type 2 prevention and early prevention of diabetes complications following the DE-PLAN project: the IMAGE (Development and Implementation of a European Guideline and Training Standards for Diabetes Prevention), the MANAGE CARE (Active Ageing with Type 2 Diabetes as Model for the Development and Implementation of Innovative Chronic Care Management in Europe) and the ePREDICE (Early Prevention of Diabetes Complications in People with Hyperglycaemia in Europe) projects (www.idf.org).

Conclusions

Type 2 diabetes prevention in primary health care setting through lifestyle intervention delivered by trained nurses leads to modest weight reduction, which is accompanied by favorable cardiovascular risk factors changes and diabetes risk reduction. These beneficial outcomes can be maintained at a 3-year follow-up.

Key messages

Type 2 diabetes prevention in high risk individuals subject to lifestyle intervention may provide long-term benefits in biological parameters such as body weight and blood lipids.

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DA:

-

QUING the China da qing diabetes prevention study

- DE-PLAN:

-

Diabetes in Europe: prevention using lifestyle, physical activity and nutritional

- DM 2:

-

Diabetes mellitus type 2

- DPP:

-

Diabetes prevention program

- DPS:

-

Diabetes prevention study

- IFG:

-

impaired fasting glucose

- IGT:

-

Impaired glucose tolerance intervention

- NGT:

-

Normal glucose tolerance

- OGTT:

-

Oral glucose tolerance test

- RCT:

-

Randomized control studies

References

Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–50.

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403.

Lindström J, Louheranta A, Mannelin M, et al. Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS): Lifestyle intervention and 3-year results on diet and physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3230–6.

Lindström J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, et al. Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet. 2006;368:1673–9.

Lindström J, Peltonen M, Eriksson JG, Ilanne-Parikka P, Aunola S, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Uusitupa M. Tuomilehto J; Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS), Improved lifestyle and decreased diabetes risk over 13 years: long-term follow-up of the randomised Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS). Diabetologia. 2013;56(2):284–93.

Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group.10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009;374:1677–86.

Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, Gregg EW, Yang W, Gong Q, Li H, Li H, Jiang Y, An Y, Shuai Y, Zhang B, Zhang J, Thompson TJ, Gerzoff RB, Roglic G, Hu Y, Bennett PH. The longterm effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371(9626):1783–9.

Schwarz PE, Lindström J, Kissimova-Scarbeck K, et al. DE-PLAN project. The European perspective of type 2 diabetes prevention: diabetes in Europe - prevention using lifestyle, physical activity and nutritional intervention (DE-PLAN) project. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2008;116:167–72.

Aleksandra G-J, Zbigniew S, Katarzyna K-S, Beata P-S, Dorota P, Roman T-M, Jaakko T, Jaana L, Markku P, Peter Eh S, Alicja H-D. Prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention in primary health care setting in Poland: Diabetes in Europe Prevention using Lifestyle, Physical Activity and Nutritional Intervention (DE-PLAN) project. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis. 2011;11:198.

Costa B, Barrio F, Cabré JJ, Piñol JL, Cos X, Solé C, Bolíbar B, Basora J, Castell C, Solà-Morales O, Salas-Salvadó J, Lindström J, Tuomilehto J; Delaying progression to type 2 diabetes among high-risk Spanish individuals is feasible in real-life primary health care settings using intensive lifestyle intervention. DE-PLAN-CAT Research Group. Diabetologia. 2012;55(5):1319–28.

Telle-Hjellset V, Råberg KjølleSDal MK, Bjørge B, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Wandel M, Birkeland KI, Eriksen HR, Høstmark AT. (The InnvaDiab-DE-PLAN study: a randomised controlled trial with a culturally adapted education programme improved the risk profile for type 2 diabetes in Pakistani immigrant women. Br J Nutr. 2012:1–10.

Viitasalo K, Hemiö K, Puttonen S, Hyvärinen HK, Leiviskä J, Härmä M, Peltonen M, Lindström J. Prevention of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases in occupational health care: Feasibility and effectiveness. Prim Care Diabetes. 2015;9(2):96–104.

Absetz P, Valve R, Oldenburg B, et al. Type 2 diabetes prevention in the ‘real world’: one year results of the GOAL Implementation Trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2465–70.

Laatikainen T, Dunbar JA, Chapman A, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention in an Australian primary health care setting: Greater Green Triangle (GGT) Diabetes Prevention Project. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:249.

Helland-Kigen KM, Råberg KjølleSDal MK, Hjellset VT, Bjørge B, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Wandel M. Maintenance of changes in food intake and motivation for healthy eating among Norwegian-Pakistani women participating in a culturally adapted intervention. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(1):113–22.

Schwarz PE, Reddy P, Greaves C, Dunbar J, Schwarz J, editors. Diabetes Prevention in Practice. Dresden: TUMAINI Institute for Prevention Management; 2010.

Yoon U, Kwok LL, Magkidis A. Efficacy of lifestyle interventions in reducing diabetes incidence in patients with impaired glucose tolerance: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Metabolism. 2013;62(2):303–14.

Johnson M, Jones R, Freeman C, Woods HB, Gillett M, Goyder E, Payne N. Can diabetes prevention programmes be translated effectively into real-world settings and still deliver improved outcomes? A synthesis of evidence. Diabet Med. 2013;30(5):632.

Dunkley AJ, Bodicoat DH, Greaves CJ, Russell C, Yates T, Davies MJ, Khunti K. Diabetes prevention in the Real World: Effectiveness of Pragmatic Lifestyle Interventions for the Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes and of the Impact of Adherence to Guideline Recommendations. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(4):922–33.

Absetz P, Oldenburg B, Hankonen N, et al. Type 2 diabetes prevention in the real world: three-year results of the GOAL lifestyle implementation trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1418–20.

Lindstrom J, Tuomilehto J. The diabetes risk score: a practical tool to predict type 2 diabetes risk. Diabetes Care. 2003;26((3):725–31.

Diabetes mellitus: report of a WHO study group. WHO Tech Rep Ser. 1985;727:7–113.

Helland-Kigen KM1, Råberg KjølleSDal MK, Hjellset VT, Bjørge B, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Wandel M. Maintenance of changes in food intake and motivation for healthy eating among Norwegian-Pakistani women participating in a culturally adapted intervention. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(1):113–22.

Hamman RF, Wing RR, Edelstein SL, Lachin JM, Bray GA, Delahanty L, Hoskin M, Kriska AM, Mayer-Davis EJ, Pi-Sunyer X, Regensteiner J, Venditti B, Wylie-Rosett J. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):2102–7.

Lahti-Koski M. Secular trends in body mass index by birth cohort in eastern Finland from 1972 to 1997. Int J Obes. 2001;25:727–61.

The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Achieving weight and activity goals among Diabetes Prevention Program lifestyle participants. Obes Res. 2004;12:1426–34.

Edelstein SL, Knowler WC, Bain RP, et al. Predictors of progression from impaired glucose tolerance to NIDDM: An analysis of six prospective studies. Diabetes. 1997;46(4):701–10.

Lantz PM. Socioeconomic status and health care. In: Smelser NJ, Baltes PB, editors. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Oxford: Elsevier Science; 2001. p. 14558–62.

Paulweber B, Valensi P, Lindström J, Lalic NM, Greaves CJ, McKee M, Kissimova-Skarbek K, Liatis S, Cosson E, Szendroedi J, et al. A European evidence-based guideline for the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42 Suppl 1:S3–36.

Lindström J, Neumann A, Sheppard KE, Gilis-Januszewska A, Greaves CJ, Handke U, Pajunen P, Puhl S, Pölönen A, Rissanen A, Roden M, Stemper T, Telle-Hjellset V, Tuomilehto J, Velickiene D, Schwarz PE, et al. Take action to prevent diabetes-the IMAGE toolkit for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in Europe. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42 Suppl 1:S37–55.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the nurses – diabetes prevention managers, dietitian, physical activity specialist Grzegorz Głąb and psychologist Danuta Łopalewska without whom this work would not have been possible. We are very grateful for the time and expertise they devoted to the performance of the DE-PLAN study.

Funding

The study was funded by The Commission of the European Communities, Directorate C – Public Health, grant agreement no. 2004310, supported by The Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland, grant agreement no. 40/PUBLIC HEALTH 2004/2006/7.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Authors’ contributions

AGJ initiated the study and participated in its design and coordination as well as drafted the manuscript. JL participated in: the design of the study, interpretation of data, revising the manuscript for important intellectual content.. JT participated in: the design of the study, revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. BPS participated in the design of the study. RTM performed the statistical analysis. ZS participated in the design of the study. MP has been involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. MP has been involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. PS has been involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. AW has been involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. AHD has been involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests (political, personal, religious, ideological, academic, intellectual, commercial or any other) to declare in relation to this manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study followed the Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration. The study protocol was approved by the Jagiellonian University Ethics Committee. The committee’s reference number is KBET/43/L/2006. All study participants gave their written informed consent prior to the participation in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gilis-Januszewska, A., Lindström, J., Tuomilehto, J. et al. Sustained diabetes risk reduction after real life and primary health care setting implementation of the diabetes in Europe prevention using lifestyle, physical activity and nutritional intervention (DE-PLAN) project. BMC Public Health 17, 198 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4104-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4104-3