Abstract

Background

In many low and middle income countries (LMICs), the distribution of adulthood nutritional imbalance is shifting from a predominance of undernutrition to overnutrition. This complex problem poses a huge challenge to governments, non-state actors, and individuals desirous of addressing the problem of malnutrition in LMICs. The objective of this study was to systematically review the literature towards providing an estimate of the prevalence of overweight and obesity among adult Ghanaians.

Methods

This study followed the recommendations outlined in the PRISMA statement. Searches were performed in PubMed, Science Direct, google scholar, Africa Journals Online (AJOL) and the WHO African Index Medicus database. This retrieved studies (published up to 31st March 2016) that reported overweight and obesity prevalence among Ghanaians. All online searches were supplemented by reference screening of retrieved papers to identify additional studies.

Results

Forty-three (43) studies involving a total population of 48,966 sampled across all the ten (10) regions of Ghana were selected for the review. Our analysis indicates that nearly 43% of Ghanaian adults are either overweight or obese. The national prevalence of overweight and obesity were estimated as 25.4% (95% CI 22.2–28.7%) and 17.1% (95% CI = 14.7–19.5%), respectively. Higher prevalence of overweight (27.2% vs 16.7%) and obesity (20.6% vs 8.0%) were estimated for urban than rural dwellers. Prevalence of overweight (27.8% vs 21.8%) and obesity (21.9% vs 6.0%) were also significantly higher in women than men. About 45.6% of adult diabetes patients in Ghana are either overweight or obese. At the regional level, about 43.4%, 36.9%, 32.4% and 55.2% of residents in Ashanti, Central, Northern and Greater Accra region, respectively are overweight or obese. These patterns generally mimic the levels of urbanization. Per studies’ publication years, consistent increases in overweight and obesity prevalence were observed in Ghana in the period 1998–2016.

Conclusions

There is a high and rising prevalence of overweight and obesity among Ghanaian adults. The possible implications on current and future population health, burden of chronic diseases, health care spending and broader economy could be enormous for a country still battling many infectious and parasitic diseases. Public health preventive measures that are appropriate for the Ghanaian context, culturally sensitive, cost-effective and sustainable are urgently needed to tackle this epidemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

For decades, undernutrition has been the focus of nutrition agendas in many countries, particularly in low and middle income countries (LMICs). Whereas infectious and parasitic diseases remain major unresolved health problems in many LMICs, emerging non-communicable diseases (NCDs) relating to diet, lifestyle, and overweight/obesity have been increasing over the last three decades [1]. The influence of the demographic transition, epidemiologic transition, and currently nutrition transition on the current state of global health is well characterized [2].

The nutrition transition is characterized by a shift in disease burden from undernutrition to overnutrition-related chronic diseases. The key drivers of nutrition transition include economic development and rapid urbanization that facilitates shifts in dietary patterns from traditional diets such as those rich in complex carbohydrates and fiber to energy-rich foods high in fat and sweeteners [3, 4]. This alongside increased sedentary lifestyle lead to obesity and related chronic diseases [5, 6]. In many developing countries, the rising over-nutrition comes along with significant burden of under-nutrition, and multiple micronutrient deficiencies resulting in a complex “multiple burden of malnutrition” [7].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), obesity remains “one of today’s most blatantly visible–yet most neglected–public health problems” [8]. Prevalence of obesity across the world has increased more than 200% since 1980 with nearly 2 billion adults estimated to be overweight in 2014 including 600 million individuals who were obese [9]. On the other hand, the prevalence of under-nutrition has not changed significantly over the last decade [10].

Overweight and obesity are used to represent abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that has the potential to exert negative effects on health [8, 11]. Obesity occurs when calories intake exceeds the energy requirements of the body both for physical activity and for growth [12]. The increasing prevalence of obesity is widely attributed to genetic factors, changes in dietary and physical activity patterns and the increasing availability of high fatty foods [11, 12]. As noted earlier, the driving forces behind these trends include globalization, which is recognized to be dictating a widespread “nutrition transition” in many countries characterized by a shift from traditional to western diets and an increasing sedentary lifestyle [13, 14].

The nutritional status of a person is frequently described by the Body Mass Index (BMI), which is the ratio of the weight (Kg) and the square of height (metres). Over the years, the BMI has widely been used to assess overweight and obesity in adults [9]. Individuals are categorized according to BMI as follows; underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2); normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2); overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥30 kg/m2) [15, 16].

Underweight, overweight and obesity are known risk factors for NCDs [17, 18]. Raised BMI (overweight/obesity) is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, hypertension, musculoskeletal disorders and some cancers [11–13]. The overall impact of obesity/overweight on physical and mental health as well as health-related quality of life is significant [19]. In countries where the economic impact of obesity has been studied, its direct (arising from preventive, diagnostic, and treatment services) and indirect (related to decreased productivity, increased absenteeism and restricted activity etc.) costs have been estimated to be enormous. In the UK, the direct and indirect costs of obesity have been estimated to be far in excess of 2 billion pounds sterling per year [20], while in the US, absenteeism arising from obesity alone has been estimated to cost as much as $4.3 billion annually [21].

Once conditions of the developed world, overweight and obesity are now prevalent in many low- and middle-income countries [22, 23]. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the rising prevalence of overweight and obesity co-exists with the under-nutrition epidemic [24, 25] and the increasing prevalence of NCDs with an anticipated largest increase in NCD deaths of 27% in Africa over the next decade [26].

In Ghana, obesity/overweight have been recognized to be increasing public health problem that could impact significantly on national resources [27, 28]. The Ghana Demographic and Health Surveys (GDHS) from 1993 to 2014 reported an increasing prevalence of obesity among Ghanaian women (15–49 years) from 3.4% to 15.3% [29–31]. The WHO estimates that in 2008, around 7.5% of Ghanaians were obese with higher prevalence in women (10.9%) than men (4.1%) [32]. A meta-analysis including studies from Ghana reported an obesity prevalence of 10% among adults in West Africa, with women being three times more likely to be obese than men (odds ratio = 3.16). However, this may not fully represent the pertaining Ghanaian situation as almost half of all the included studies (46.4%) in the review were from Nigeria [10]. In our literature search, we identified one systematic review by Commodore-Mensah et al. [33], which reported overweight/obesity prevalence in Ghanaian adults as within the range 20–62%. Aside the wide range presented, this review involved only nine (9) studies published no later than June 2012 and excluded high risk groups as well as studies conducted in hospital settings. While the 2013 global burden of disease study also reported overweight and obesity prevalence in Ghanaian adult (>20 years) males (overweight = 15 · 4%; obesity = 2.5%) and females (overweight = 29.1%, obesity = 9.8%), these estimates were based on data selected from only nine survey reports [26]. Additionally, none of the previously published reviews provide clues as to the temporal changes in overweight and obesity prevalence in Ghana.

Our general observation points to a lack of thorough systematic review of the literature towards documenting the prevalence of overweight and obesity in Ghana. To support evidence-based policymaking, resource allocation and the design of appropriate public health interventions, accurate overweight and obesity prevalence estimates based on thorough and up-to-date evidence compilation is urgently needed. In this study, we conducted a systematic review to summarize the available information to date towards estimating the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Ghanaian adults. Additionally, we sought to assess the temporal changes in overweight and obesity prevalence in the country.

Methods

This review adhered to the recommendations outlined in the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement [34] (Additional file 1).

Search strategy

Searches were conducted in PubMed, Science Direct, google scholar, Africa Journals Online (AJOL) and the WHO African Index Medicus database to retrieve primary studies reporting overweight and obesity prevalence among Ghanaians. The keywords used in our searches were “obesity OR overweight OR anthropometry OR adiposity” AND “prevalence” AND “Ghana OR Ghanaian”. All searches were conducted between 20/03/2016 and 31/03/2016 by RO and AAA. References of all selected papers were screened along with those of previously published reviews with the aim of identifying additional studies which may have been missed through our online searches.

Inclusion and exclusion of studies

We included studies published up to 31st March 2016 which reported overweight and obesity prevalence among Ghanaians adults (≥18 years). RO and AAA conducted titles and abstract screening against the pre-defined study inclusion criteria. Additionally, full-text articles were also independently screened by the same reviewers (AAA, RO) for eligibility. To allow for aggregation/pooling of data, we only included studies that used BMI to define overweight and obesity prevalence. We classified BMI of 25–29.9 kg/m2 and ≥ 30 kg/m2 to represent overweight and obesity in adults, respectively [15, 16]. Studies were included only if BMI was stratified and separate prevalence of overweight and/or obesity were presented. We excluded studies conducted in children as the focus in this review was on adults. Studies presenting self-reported overweight and obesity prevalence were excluded as these have been found to usually underestimate overweight and obesity prevalence [35, 36]. For studies with multiple publications, the version published first or one with complete dataset was selected. We assessed the quality of studies, based on a 12-point scoring system adopted from the Downs and Black checklist [37]. For each study, descriptive details such as author details, publication year, region where study was conducted, study design, type of setting (e.g. rural), the study population, mean age of participants and the overweight and obesity prevalence rates were collected. Data were independently extracted by RO, AAA and DB and crosschecked. Any disparities in data were resolved by consensus-based discussions among the authors.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis and meta-analysis proportions were carried out using OpenMeta (analyst) software, an open-source, cross-platform software for advanced meta-analysis [38] and StatsDirect statistical software (Version 3.0.0, StatsDirect Ltd, Cheshire UK) [39]. The pooled effects and individual study proportions were assessed at 95% confidence interval (CI). We performed heterogeneity test for all the proportions based on Cohran’s heterogeneity statistic (Q) and degree of inconsistency (I2) [40]. I2 > 50% was considered to denote meaningful heterogeneity in which case the random effect model (DerSimonian-Laird) was used instead of the fixed effect model in the analysis of pooled effects [40]. The presence of publication bias was assessed by direct observation of funnel plots as well as through Egger and Begg’s regression tests [41, 42]. We assessed the robustness of the pooled estimates by conducting a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis to assess the impacts that each study exerts on the overall pooled estimate [43]. Furthermore, sub-analysis was carried out across gender and settings (urban vs rural), across studies’ publication periods as well as for specific populations such as persons with diabetes. In all analysis, we considered statistical significance to represent p < 0.05.

Results

Overview of studies

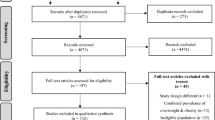

Figure 1 represents the PRISMA flow chart outlining the steps in retrieving appropriate studies for the review. A total of 2482 citations were identified through electronic search and other sources. After the exclusion of duplicates and assessment of titles and abstracts, 59 articles were shortlisted for detailed full-text analysis. Out of this number, 41 met the inclusion criteria for addition to the review. Two (2) additional studies were retrieved through reference screening of selected papers bringing the total number of studies included in the review to 43 [44–86]. These 43 studies (Table 1) involved a sample population of 48,966 with individual study sample size ranging from 59 to 9215. The studies were conducted across all the 10 regions of Ghana and included 4 nationally-sampled studies [60, 70, 76, 86]. Regional-based studies were distributed as follows; Ashanti (n = 11), Greater Accra (n = 15), Northern (n = 7), Volta (n = 1), Upper East (n = 1), Central (n = 3) and one inter-regional study (Greater Accra and Upper West). While twelve (12) studies did not report the actual period (year/s) in which sampling was conducted, in the remaining 31 studies sampling were conducted between 1988 and 2016. Per publication years, 93% (n = 40) of studies were published within the last decade (2006–2016) and 79% (n = 34) were published within the last 5 years (2011–2016). Applying the quality assessment criteria, 56%, 35% and 9% of studies were graded as high, medium and low quality, respectively.

Overweight prevalence among Ghanaian adults

Overweight prevalence data was retrieved from 39 studies with a combined sample size of 39,202. Among these studies, the reported overweight prevalence ranged from 5.8% to 54.0%. The pooled national prevalence of overweight (Fig. 2) among Ghanaian adults from the 39 studies was estimated as 25.4% (95% CI 22.2–28.7%). I2 was determined as 98.51% (p < 0.001) for the degree of inconsistency. A funnel plot of the overweight prevalence showed presence of publication bias as depicted by an asymmetrical display of prevalence reported by various studies (Fig. 3). This was confirmed by an Egger’s test which was significant (p < 0.0001). A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis also revealed that the pooled estimate was most impacted by prevalence data from Nelson et al. [75] (Fig. 4).

Overweight prevalence among males was determined as 21.8% (95% CI = 16.2–27.4%; I2 = 98.43%, p < 0.001). Among females, overweight prevalence information was collected from thirty (30) studies with a total sample size of 22,079. Reported overweight prevalence for females from these studies was within the range 8.4–66.6% and the pooled estimate was determined as 27.8% (95% CI 24.4–31.3%; I2 = 97.27%, p < 0.001). The difference (6.0%; 95% CI 5.0–7.0%) in overweight prevalence between males and females was statistically significant (p < 0.0001).

Overweight prevalence among adults with diabetes was estimated using data from 4 studies with a combined sample size of 1663. The pooled overweight prevalence among the diabetics was estimated as 30.0% (95% CI = 22.1–37.8%; I2 = 91.89%, p < 0.001).

Overweight prevalence among rural dwellers was estimated using data from nine (9) studies with a combined sample size of 10,803. The overweight prevalence was within the range 4.8–43.9%. The pooled overweight prevalence in rural dwellers was estimated as 16.7% (95% CI 11.2–22.3%; I2 = 98.3%, p < 0.001). Overweight prevalence among urban dwellers was estimated using information from 32 studies that together involved a total sample population of 23,465. Among the 32 studies the overweight prevalence among urban dwellers was within the range 5.8–54%. The pooled overweight prevalence among urban dwellers was estimated as 27.2% (95% CI 23.7–30.7%; I2 = 97.53%, p < 0.001). The difference (10.5%, 95% CI 9.6–11.4%) in overweight prevalence between urban and rural dwellers was statistically significant (p < 0.0001).

Overweight prevalence for Ashanti, Greater Accra, Northern and Central regions were estimated based on data from 11 (sample population size = 5887), 15 (sample population size = 14,834), 7 (sample population size = 2715) and 3 (sample population size = 932) studies respectively, as follows; Ashanti = 26.9% (95% CI 20.7–33.0; I2 = 96.65%, p < 0.001); Greater Accra = 30.1% (95% CI 26.2–33.9; I2 = 96.1%, p < 0.001); Northern = 21.9% (95% CI 13.8–29.9; I2 = 96.87% p < 0.001) and Central region = 16.0% (95% CI 7.3–24.7%; I2 = 92.82%, p < 0.001). We were unable to estimate overweight prevalence for the six (6) remaining regions due to limited number of studies reporting prevalence for these regions.

Obesity prevalence among Ghanaian adults

Obesity prevalence data was retrieved from forty-two (42) studies with a combined sample size of 48,811. Among these studies, the reported obesity prevalence was within the range 1.6–63.8%. The pooled national prevalence of obesity (Fig. 5) among Ghanaian adults based on the 42 studies was estimated as 17.1% (95% CI = 14.7–19.5%). I2 was determined as 98.9% (p < 0.001) for the degree of inconsistency. A funnel plot of obesity prevalence rates showed presence of publication bias as depicted by an asymmetrical display of prevalence reported by various studies (Fig. 6). This was confirmed by an Egger’s test which was significant (p < 0.0001). A leave-one-out analysis revealed that the pooled obesity prevalence estimate was most impacted by Aidoo et al. [49] (Fig. 7).

Obesity prevalence among males was retrieved from seventeen (17) studies with a total sample population size of 10,550. These 17 studies reported obesity prevalence in the range 0.6–38%. The pooled obesity prevalence estimate for males was estimated as 6.0% (95% CI 4.4–7.6%; I2 = 95.3%; p < 0.001). Obesity prevalence among females was retrieved from twenty-nine (29) studies with a total sample size of 21,079. These 29 studies reported obesity prevalence in the range 2–55%. The pooled obesity prevalence estimate was determined as 21.9% (95% CI 17.7–26.2%; I2 = 98.74%, p < 0.001). The difference (15.9%; 95% CI 15.2–16.6%) in obesity prevalence between males and females was statistically significant (p < 0.0001).

Among diabetes patients, the obesity prevalence was estimated using data from 4 studies with a combined sample size of 1663. The pooled obesity prevalence estimate was determined 15.6% (95% CI 11.2–20.0%; I2 = 83.92%, p < 0.001).

Prevalence of obesity in rural settings was estimated using data from 11 studies with a total sample population of 13,913 and individual prevalence rates ranging from 1.4% to 40.5%. The pooled obesity prevalence estimate for rural dwellers was estimated as 8.0% (95% CI 5.4–10.5%; I2 = 97.9%; p < 0.001). For urban dwellers, obesity prevalence data was retrieved from 33 studies with a total sample population of 25,240. The individual prevalence reported was within the range 1.9–63.8% and the pooled estimate was determined as 20.6% (95% CI 16.9–24.3%; I2 = 98.99%, p < 0.001. The difference (12.6%, 95% CI 11.9–13.2%) in obesity prevalence between urban and rural dwellers was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.0001).

Obesity prevalence for Ashanti, Greater Accra, Northern and Central regions were estimated based on data from 11 (sample population size = 5887), 16 (sample population size = 14,840), 7 (sample population size = 2715) and 3 (sample population size = 932) studies respectively, as follows; Ashanti 16.5% (95% CI 10.8–22.3%; I2 = 97.67%, p < 0.0001); Greater Accra 25.1% (95% CI 20.0–30.1; I2 = 98.2%, p < 0.0001); Northern region 10.5% (95% CI 5.9–15.2; I2 = 96.59% P < 0.0001) and Central region = 20.9% (95% CI 10.6–31.2; I2 = 93.92% p < 0.001). We were unable to deduce obesity prevalence estimates for the remaining seven regions of Ghana due to limited number of individual prevalence data from studies (Fig. 8).

Temporal changes in overweight and obesity prevalence among Ghanaian adults

As 28% (n = 12) of studies did not report the actual period (year/s) in which sampling were carried out, we resorted to a temporal analysis based on years in which studies were published. We grouped studies into the publication periods 1998–2006, 2007–2013 and 2014–2016 with a distribution of 7, 14 and 22 studies, respectively. The overweight prevalence for the periods 1998–2006, 2007–2013 and 2014–2016 were estimated as 18.6% (95% CI 13.1–24.1%; I2 = 99.0%, p < 0.0001), 25.0% (95% CI 20.6–29.3%; I2 = 95.04%, p < 0.0001) and 28.5% (95% CI 23.3–33.7%; I2 = 97.44%, p < 0.0001), respectively. Thus, the ascending order of overweight prevalence among Ghanaian adults according to studies’ publication period was 1998–2006 < 2007–2013 < 2014–2016. Obesity prevalence for the periods 1998–2006, 2007–2013 and 2014–2016 were also estimated as 11.3% (95% CI 7.6–15.0%; I2 = 98.9%, p < 0.0001), 18.0% (95% CI 12.4–23.6%; I2 = 97.57%, p < 0.0001), and 18.4% (95% CI 15.0–21.7%; I2 = 98.56%, p < 0.0001), respectively. Hence the ascending order of obesity prevalence among Ghanaian adults according to studies publication period was 1998–2006 < 2007–2013 < 2014–2016 (Fig. 9).

Discussion

This review has documented a high prevalence of overweight (25.4%) and obesity (17.1%) among Ghanaian adults. Higher prevalence of overweight and obesity across studies published in the most recent years (2007–2016) as opposed to those published in earlier years (1998–2006) by inference highlight the growing burden of overweight and obesity in the country. The rising overweight and obesity burden as observed in this review is in line with observations already communicated by other researchers in the country [28, 87] and is further supported by the reported consistent increase in obesity/overweight prevalence by the Ghana DHS in the period 1988–2014 [29–31]. Our results and those of others all suggest and corroborate the fact that obesity is no more an issue of only “affluent nations” but becoming an increasing public health problem in LMICs such as Ghana.

For decades, undernutrition has traditionally been the focus of nutrition agendas in many LMICs. Whereas common infectious and parasitic diseases (e.g. Malaria, HIV and TB) remain major unresolved health problems in many LMICs [88], emerging NCDs relating to diet and lifestyle have been increasing over the last three decades; often times attributed to the demographic transition, epidemiologic transition, and currently nutrition transition [2, 89]. Facilitated by rapid economic development and urbanization [5], the nutrition transition is characterized by a shift in disease burden from undernutrition to overnutrition-related chronic diseases. Increased consumption of energy-dense foods and the lack of physical activity, which are marked characteristics of advancing nutrition transition, lead to obesity and the development of numerous chronic diseases. This has led to an increase in overweight and obesity and their-related chronic diseases [6].

While our analysis points to a growing problem of obesity, undernutrition still poses significant threat to health and wellbeing of many Ghanaians. In the 2014 DHS for instance, over 6% of Ghanaian women were found to be underweight [29]. This co-existence of undernourishment and overnutrition is a real public health challenge particularly among lower socioeconomic groups [90], who may lack the financial resources to avoid micronutrient-poor diet but may also be more likely to consume cheaper processed and energy-dense meals [91]. Evidence suggests that in many LMICs, increasing numbers of lower socioeconomic groups struggle with undernutrition, even as obesity and overnutrition increases [92].

Several theories (such as life-course perspective) have been proposed to explain this phenomenon of rising obesity among populations with systemic undernutrition challenges [89]. Amuna and Zotor [93], explain that fetal exposure to maternal malnutrition during pregnancy could increase risk of nutritional disorders in later life. Another explanation also points to the role that poor childhood nutrition (i.e. stunting, underweight) could impact future physiological pathways. For instance, poor nutritional status during early stages of development may boost the development of thrifty phenotype that may increase risks of chronic conditions including obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases in later life [94–96]. Additionally, infections contracted at early life years can also increase future risk of NCDs such as obesity [89, 97]. This may be an important component particularly in LMICs were infectious diseases remain highly prevalent and children are often at high risk [98, 99].

In this review, we report a 1.3 times higher prevalence of overweight and about 3.7 times higher prevalence of obesity in women as compared to men. This trend is consistent with results from a previous review by Abubakari et al. [10] in which West African women were 3 times more likely to be obese than their male counterparts. The higher prevalence of overweight and obesity among women than men in Ghana is also consistent with globally observed gender difference in overweight and obesity patterns [9].

Although, physiological pathways such as the differences in body fat distribution and the influence of gonadal steroids on appetite have sometimes been used to explain gender differences in anthropometric indices [100], the influence of behavioral and socio-cultural factors remain extremely important [101, 102]. In Ghana, women tend to settle for more sedentary occupations (e.g. table-top trading) and research has documented lower levels of physical activity among Ghanaian women than men. In a study of the predictors of overweight and obesity among a cohort of urban Ghanaian women, just around 21% were found to maintain adequate physical activity levels [54]. In a similar recent study among urban youth in Accra, about 4 in 5 (84.1%) persons were found to be physically inactive, with rates higher in females (94.7%) than males (70.5%) [103]. Additionally, studies have reported that many Ghanaian communities show great admiration towards large body size [59, 104]. Often, large body size is considered as a sign of “affluence” and women also tend to perceive this as constituting “beauty, good health and happiness in marriage” [54]. Anecdotal evidence suggest that in some Ghanaian communities with high HIV prevalence, the attainment of a large body size is sometimes misconstrued to mean a “virus-free” status and many individuals therefore desire large body size to avert any stigma. These socio-cultural construction of ideal body size may be implicated in the rising overweight and obesity burden in the country.

Our analysis also brings to bear the impacts of urbanization on the overweight/obesity epidemic in Ghana as confirmed by the near 1.6 and 2.6 fold increase in overweight and obesity prevalence, respectively among urban dwellers as compared to their rural counterparts. The differences in overweight/obesity prevalence in Ashanti, Northern, Central and Greater Accra regions also broadly mimic the extent of urbanization. Greater Accra, being the region that harbors the capital city has experienced the most rapid urbanization compared to any part of the country. In 2000 for instance, 87.4% of the population in Greater Accra region resided in urban centres compared to 53.2% for Ashanti and 27.0% for Northern regions [105]. Regardless, the extent of urbanization may not be the only underlying factor for the regional variation in overweight/obesity prevalence as cultural/tribal variations have been observed. Amoah [106], for instance reported highest overweight and obesity prevalence among the Akan and Ga tribes and relatively low rates among Ewes. Similar results were obtained by Agbeko et al. [107] after a secondary analysis of data from the 2008 DHS. The variations in overweight and obesity prevalence among the ethnic groups are thought to broadly reflect differences in social behaviors including work patterns, meal preparation and perception of body size.

Ghana like many other countries is also experiencing its fair share of the impacts of globalization. Over the last three (3) decades, the country has seen dramatic changes in telecommunication, transportation and exposure to the global market. Today, almost every household has someone owning a mobile phone compared to 1996 when there were just around three telephone lines per 1000 Ghanaians [14]. More Ghanaians now have access to internet and combined with other improved communication channels, exposure to foreign lifestyle and marketing has increased greatly. The effects of these is being witnessed in the form of drastic lifestyle changes including westernization of diet and high levels of sedentary lifestyle which have gained great momentum particularly in urban centres [14]. Studies have pointed out that “the nutrition transition and the rise in technology-aided, sedentary lifestyles (cars, computers at home and in internet cafes, games consoles for elite and middle class youth) are strongly implicated in Ghana’s obesity and chronic disease epidemics” [87]. Alcohol consumption have all been given significant boost and evidence suggests that Ghanaians who consume excessive alcohol have higher risks of overweight and obesity [60, 107]. Furthermore, as Ofori-Asenso and Garcia [14] discussed, the built environment in many urban centres in Ghana have not evolved to meet the expanding population; roads are usually congested and there are not many sidewalks or parks that could encourage physical activities like running and walking. These poor urban planning if not properly addressed could be a catalyst for further escalation of obesity in the country even as other factors drive an obesogenic environment. The prevalence of overweight/obesity in the rural areas reported in this review is also a call for concern and action as this is high compared to what has been reported in the past [32]. This highlights that the increasing obesity and overweight prevalence in Ghana may be more widely spread than previously thought. To fully explore the contribution of the urban environment to the obesity/overweight burden, further research could focus for instance on assessing how individuals’ risk profiles change once they migrate from rural to urban centres and vice versa.

While in many high-income countries, obesity tends to be more prevalent in persons with lower socioeconomic status (SES), the reverse has been the case in many low-income countries [108]. Studies by Amoah [106] and Appiah et al. [54] have documented higher prevalence of overweight/obesity in high-class Ghanaians compared with the low class residents. Additionally, Ghanaians with tertiary education have been found to have the highest prevalence of obesity compared with less literate and illiterate subjects. This may tie in to the perceptions of larger body size and affluence in many Ghanaian communities [59], but may also relate to the fact that increasing affluence may come with increased choice and accessibility to food and may promote intake of larger portion sizes [54, 109]. Moreover, evidence suggests that in Ghana, most fast-food joints and restaurants are crowded in wealthy neighborhoods and tend to target high-class clientele [110]. Agyei-mensah and de-Graft Aikins [87], also report that among the working (middle to high class) population in Ghana, “there is an emerging trend of individuals working late or hanging out at after-work bars to beat the heavy evening traffic; these practices are implicated in late eating and increased alcohol intake, and by extension increased chronic disease risks”.

The high and rising burden of overweight and obesity as documented in this study should be a concern to nutritional scientists, health workers and government of Ghana due to the impact on health and a possibility of a an explosion of chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes or even cancers [9]. Already, the prevalence of diseases like hypertension and diabetes are increasing significantly. Addo et al. [111], for instance, reported a high prevalence of hypertension in Ghana ranging from 19.3% in rural to 54.6% in urban areas with factors such as increased salt intake and increasing BMI being implicated in the rising prevalence. The prevalence of type-2 diabetes in Ghana in 2014 was estimated as 6% with over 450,000 persons living with the disease [14]. These rates are about 15 times high when compared to prevalence of about 0.4% in 1956 [112]. The impacts of overweight and obesity on individuals’ wellbeing and on productivity means that if the trends observed persists, the consequences on Ghana’s economic indicators can be enormous. Yet in Ghana, government’s effort continually focus on reducing hunger and in many instances neglect the growing problem of overweight/obesity. De graft Aikins [113], attributes this to longstanding misconception that NCDs and risk factors including obesity do not pose significant health challenges. To address the rising problem of overweight/obesity in Ghana, greater commitment from government will be needed to ensure efficient resource allocation and also to provide broader policy framework within which interventions can be implemented [114, 115]. Approaches adopted should be broad in nature and must not undermine undernutrition prevention efforts but should focus on tackling all aspects of malnutrition (over/undernutrition) to ensure a “sustainable nutrition for all” Ghanaians [116].

Strengths and limitations

This review presents a stronger evidence regarding the prevalence of overweight/obesity among Ghanaian adults as it is based on larger number of studies than previously published reviews. Regardless, it has some limitations. Firstly, while the review covered studies that collected data from all regions of Ghana, there was a significant regional imbalance with 60% of studies conducted in two regions, Ashanti and Greater Accra alone. Subsequently, pooled estimates were not available for six (6) regions. The regional imbalance in data is likely to shift estimates as more evidence on overweight and obesity prevalence in the under-represented regions become available. Secondly, most studies did not report on the prevalence across broad socio-demographic characteristics such as religion, family size, marital status and ethnicity, although, these have all been identified as useful predictors of overweigh and obesity [117, 118]. Furthermore, a high level of heterogeneity across studies was observed including the presence of publication bias. The assessment of overweight/obesity among diabetes patients were also based on limited studies and dominated by those conducted in urban patients. Our temporal analysis of overweight/obesity prevalence was also based on studies’ publication years. A more robust approach for this analysis would have required the use of midpoint of actual study/sampling periods [119]. The use of publication period as opposed to actual period in which study/sampling was conducted may introduce some bias as there can be a time-lag between when a study is conducted is when it is published. In spite of the limitations outlined, the prevalence of overweight and obesity presented in this review should speak to current situation as most studies were recently published, including 79% of studies published within the last 5 years (2011–2016). The prevalence information on overweight and obesity presented should guide and inform policy makers in terms of resource allocation and planning towards controlling the rising burden of obesity and overweight in this country.

Conclusions

Evidence available supports a high and rising prevalence of overweight and obesity among Ghanaian adults. This presents a significant public health issue, and the implications on current and future population health, burden of chronic diseases and on health care spending can be enormous for a country that is still battling many infectious and parasitic diseases. Further research is needed to provide greater insights into the major drivers underlying the rising overweight and obesity epidemic and also to offer context in terms of documenting the regional difference in prevalence. Urgent population-wide interventions and policy directions that assume broad approaches, are culturally acceptable, cost-effective and sustainable are clearly needed to tackle this emerging epidemic.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DHS:

-

Demographic and Health Surveys

- HDI:

-

Human development index

- LMICs:

-

Low and middle income countries

- MDG:

-

Millennium Development Goals

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- NHIS:

-

National health insurance scheme

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Boutayeb A. The double burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases in developing countries. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100(3):191–9.

Kuate Defo B. Demographic, epidemiological, and health transitions: are they relevant to population health patterns in Africa? Glob Health Action. 2014;7:22443.

Kearney J. Food consumption trends and drivers. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 2010;365(1554):2793–807.

Drewnowski A, Popkin BM. The nutrition transition: new trends in the global diet. Nutr Rev. 1997;55(2):31–43.

Popkin BM. The nutrition transition in low-income countries: an emerging crisis. Nutr Rev. 1994;52(9):285–98.

Ng SW, Popkin BM. Time use and physical activity: a shift away from movement across the globe. Obes Rev. 2012;13(8):659–80.

Downs S. The Multiple Burdens of Malnutrition; Food system drivers and solutions. Sight Life. 2016;30(1):41–5.

Controlling the global obesity epidemic. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/obesity/en/. Accessed 1 Aug 2016.

Obesity and Overweight: Factsheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/. Accessed 12 Aug 2016.

Abubakari AR, Lauder W, Agyemang C, Jones M, Kirk A, Bhopal RS. Prevalence and time trends in obesity among adult West African populations: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2008;9(4):297–311.

Marinou K, Tousoulis D, Antonopoulos AS, Stefanadi E, Stefanadis C. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: from pathophysiology to risk stratification. Int J Cardiol. 2010;138(1):3–8.

Escalona A, Sarfo M, Kudua L. Obesity and systemic hypertension in Accra communities. Ghana Med J. 2004;38:145–8.

Hawkes C. Uneven dietary development: linking the policies and processes of globalization with the nutrition transition, obesity and diet-related chronic diseases. Glob Health. 2006;2:4.

Ofori-Asenso R, Garcia D. Cardiovascular diseases in Ghana within the context of globalization. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2016;6(1):67–77.

Wang Y. Epidemiology of childhood obesity—methodological aspects and guidelines: what is new? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28 Suppl 3:S21–8.

Jafari-Adli S, Jouyandeh Z, Qorbani M, Soroush A, Larijani B, Hasani-Ranjbar S. Prevalence of obesity and overweight in adults and children in Iran; a systematic review. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13(1):121.

Kozak AT, Daviglus ML, Chan C, Kiefe CI, Jacobs Jr DR, Liu K. Relationship of body mass index in young adulthood and health-related quality of life two decades later: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study. Int J Obes. 2011;35(1):134–41.

Sairenchi T, Iso H, Irie F, Fukasawa N, Ota H, Muto T. Underweight as a predictor of diabetes in older adults: a large cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(3):583–4.

Dixon JB. The effect of obesity on health outcomes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316(2):104–8.

Vlad I. Obesity costs UK economy 2bn pounds sterling a year. BMJ. 2003;327(7427):1308.

Cawley J, Rizzo JA, Haas K. Occupation-specific absenteeism costs associated with obesity and morbid obesity. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(12):1317–24.

Campbell T, Campbell A. Emerging disease burdens and the poor in cities of the developing world. J Urban Health. 2007;84(3 Suppl):i54–64.

World Health Organisation. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Health Synthesis: A report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

Agyemang C, Owusu-Dabo E, de Jonge A, Martins D, Ogedegbe G, Stronks K. Overweight and obesity among Ghanaian residents in The Netherlands: how do they weigh against their urban and rural counterparts in Ghana? Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(7):909–16.

Assah FK, Ekelund U, Brage S, Corder K, Wright A, Mbanya JC, Wareham NJ. Predicting physical activity energy expenditure using accelerometry in adults from sub-Sahara Africa. Obesity. 2009;17(8):1588–95.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, Biryukov S, Abbafati C, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9945):766–81.

Ofei F. Obesity–a preventable disease. Ghana Med J. 2005;39(3):98–101.

Regional and Socio-economic Dimensions of the Obesity “Epidemic” in Ghana. http://iussp.org/sites/default/files/event_call_for_papers/Agyei%20Mensah%20and%20Dake_IUSSP%20Extended%20Abstract.pdf. Accessed 15 July 2016.

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS), ICF International. Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Rockville: GSS, GHS, and ICF International; 2015.

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Demographic and Health Surveys Institute for Resource Development/Macro Systems Inc. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 1988. Maryland USA: Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) and Demographic and Health Surveys Institute for Resource Development/Macro Systems Inc; 1989.

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (NMIMR), ORC Macro. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Calverton: GSS, NMIMR, and ORC Macro; 2004.

World Health Organization–Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles, 2014. http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/gha_en.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 15 July 2016.

Commodore-Mensah Y, Samuel LJ, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Agyemang C. Hypertension and overweight/obesity in Ghanaians and Nigerians living in West Africa and industrialized countries: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2014;32(3):464–72.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–12.

Cameron R, Evers S. Self-report issues in obesity and weight management: State of the art and future directions. Behav Assess. 1990;12(1):91–106.

Stommel M, Schoenborn CA. Accuracy and usefulness of BMI measures based on self-reported weight and height: findings from the NHANES & NHIS 2001–2006. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:421.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84.

Wallace B, Issa J, Trikalinos T, Lau J, Trow P, Schmid C. Closing the Gap between Methodologists and End-Users: R as a Computational Back-End. J Stat Softw. 2012;49(5):1–15.

Proportion Meta-analysis. http://www.statsdirect.com/help/default.htm#meta_analysis/proportion.htm. Accessed 1 June 2016.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Begg CB, Berlin JA. Publication bias and dissemination of clinical research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(2):107–15.

Higgins JP. Commentary: Heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be expected and appropriately quantified. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(5):1158–60.

Abubakari A, Kynast-Wolf G, Jahn A. Maternal Determinants of Birth Weight in Northern Ghana. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135641.

Addo J, Amoah AG, Koram KA. The changing patterns of hypertension in Ghana: a study of four rural communities in the Ga District. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(4):894–9.

Addo J, Smeeth L, Leon DA. Obesity in urban civil servants in Ghana: association with pre-adult wealth and adult socio-economic status. Public Health. 2009;123(5):365–70.

Addo PN, Nyarko KM, Sackey SO, Akweongo P, Sarfo B. Prevalence of obesity and overweight and associated factors among financial institution workers in Accra Metropolis, Ghana: a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:599.

Agyemang C. Rural and urban differences in blood pressure and hypertension in Ghana, West Africa. Public Health. 2006;120(6):525–33.

Aidoo H, Essuman A, Aidoo P, Yawson AO, Yawson AE. Health of the corporate worker: health risk assessment among staff of a corporate organization in Ghana. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2015;10:30.

Amegah A, Lumor S, Vidogo F. Prevalence and determinants of overweight and obesity in adult residents of cape coast, ghana: A hospital-based study. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2011;11(3):4828–46.

Amidu N, Owiredu W, Mohammed A, Dapare P, Antuamwine B, Sitsofe V, Adjeiwaa J. Obesity and Hypertension among Christian Religious Subgroups: Pentecostal vs. Orthodox. Br J Med Med Res. 2016;13(2):1–14.

Amoah AG. Sociodemographic variations in obesity among Ghanaian adults. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6(8):751–7.

Antwi E, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Quansah Asare G, Koram KA, Grobbee D, Agyepong IA. Measuring regional and district variations in the incidence of pregnancy-induced hypertension in Ghana: challenges, opportunities and implications for maternal and newborn health policy and programmes. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21(1):93–100.

Appiah C, Steiner-Asiedu M, Otoo G. Predictors of Overweight/Obesity in Urban Ghanaian Women. Int J Clin Nutr. 2014;2(3):60–8.

Arthur FK, Adu-Frimpong M, Osei-Yeboah J, Mensah FO, Owusu L. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its predominant components among pre-and postmenopausal Ghanaian women. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:446.

Arthur F, Dadson J, Yeboah-Awudzi M, Larbie C. Body mass index and its effect on rate of hospital visits of staff of Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi. Arch Appl Sci Res. 2014;6(4):198–202.

Aryee P, Helegbe G, Baah J, Sarfo-Asante R, Quist-Therson R. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Overweight and Obesity among Nurses in the Tamale Metropolis of Ghana. J Med Biomed Sci. 2013;2(4):13–23.

Aryeetey R, Ansong J. Overweight and hypertension among college of health sciences employees in Ghana. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2011;11(6):5444–56.

Benkeser RM, Biritwum R, Hill AG. Prevalence of overweight and obesity and perception of healthy and desirable body size in urban, Ghanaian women. Ghana Med J. 2012;46(2):66–75.

Biritwum R, Gyapong J, Mensah G. The epidemiology of obesity in ghana. Ghana Med J. 2005;39(3):82–5.

Blankson B, Hall A. The anthropometric status of elderly women in rural Ghana and factors associated with low body mass index. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(10):881–6.

Burket BA. Blood pressure survey in two communities in the Volta region, Ghana, West Africa. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):292–4.

Donkor C, Edusei A, Mensah K, Nkoom B, Okyere P, Appiah-Brempong E, Adjei R. Prevalence of Hypertension and Obesity among Women in Reproductive Age in the Ashaiman Municipality in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. Dev Country Stud. 2015;2(5):85–96.

Duda RB, Jumah NA, Hill AG, Seffah J, Biritwum R. Interest in healthy living outweighs presumed cultural norms for obesity for Ghanaian women. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:44.

Duda RB, Kim MP, Darko R, Adanu RM, Seffah J, Anarfi JK, Hill AG. Results of the Women’s Health Study of Accra: assessment of blood pressure in urban women. Int J Cardiol. 2007;117(1):115–22.

Ephraim RK, Osakunor DN, Denkyira SW, Eshun H, Amoah S, Anto EO. Serum calcium and magnesium levels in women presenting with pre-eclampsia and pregnancy-induced hypertension: a case-control study in the Cape Coast metropolis, Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:390.

Frank LK, Heraclides A, Danquah I, Bedu-Addo G, Mockenhaupt FP, Schulze MB. Measures of general and central obesity and risk of type 2 diabetes in a Ghanaian population. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18(2):141–51.

Kunutsor S, Powles J. Cardiovascular risk in a rural adult West African population: is resting heart rate also relevant? Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(5):584–91.

Luke A, Bovet P, Plange-Rhule J, Forrester TE, Lambert EV, Schoeller DA, Dugas LR, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Shoham DA, Cao G, et al. A mixed ecologic-cohort comparison of physical activity & weight among young adults from five populations of African origin. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:397.

Minicuci N, Biritwum RB, Mensah G, Yawson AE, Naidoo N, Chatterji S, Kowal P. Sociodemographic and socioeconomic patterns of chronic non-communicable disease among the older adult population in Ghana. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:21292.

Mogre V, Nyaba R, Aleyira S. Lifestyle risk factors of general and abdominal obesity in students of the school of medicine and health science of the university of development studies, tamale, ghana. ISRN Obes. 2014;2014:508382.

Mogre V, Salifu ZS, Abedandi R. Prevalence, components and associated demographic and lifestyle factors of the metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13:80.

Mogre V, Nyaba R, Aleyira S, Sam NB. Demographic, dietary and physical activity predictors of general and abdominal obesity among university students: a cross-sectional study. Springerplus. 2015;4:226.

Mogre V, Apala P, Nsoh JA, Wanaba P. Adiposity, hypertension and weight management behaviours in Ghanaian type 2 diabetes mellitus patients aged 20–70 years. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2016;10(1 Suppl 1):S79–85.

Nelson F, Nyarko KM, Binka FN. Prevalence of Risk Factors for Non-Communicable Diseases for New Patients Reporting to Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital. Ghana Med J. 2015;49(1):12–8.

Nube M, Asenso-Okyere WK, van den Boom GJ. Body mass index as indicator of standard of living in developing countries. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52(2):136–44.

Nyawornota VK, Aryeetey R, Bosomprah S, Aikins M. An exploratory study of physical activity and over-weight in two senior high schools in the Accra Metropolis. Ghana Med J. 2013;47(4):197–203.

Obirikorang C, Osakunor DN, Anto EO, Amponsah SO, Adarkwa OK. Obesity and Cardio-Metabolic Risk Factors in an Urban and Rural Population in the Ashanti Region-Ghana: A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129494.

Obirikorang Y, Obirikorang C, Odame Anto E, Acheampong E, Dzah N, Akosah CN, Nsenbah EB. Knowledge and Lifestyle-Associated Prevalence of Obesity among Newly Diagnosed Type II Diabetes Mellitus Patients Attending Diabetic Clinic at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, Kumasi, Ghana: A Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Study. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:9759241.

Oppong SA, Ntumy MY, Amoakoh-Coleman M, Ogum-Alangea D, Modey-Amoah E. Gestational diabetes mellitus among women attending prenatal care at Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131(3):246–50.

Owiredu W, Amidu N, Gockah-Adapoe E, Ephraim R. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome among active sportsmen/sportswomen and sedentary workers in the Kumasi metropolis. J Sci Technol. 2011;31(1):23–36.

Pereko KK, Setorglo J, Owusu WB, Tiweh JM, Achampong EK. Overnutrition and associated factors among adults aged 20 years and above in fishing communities in the urban Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(4):591–5.

Pobee R, Owusu W, Plahar W. The prevalence of obesity among female teachers of child-bearing age in ghana. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2013;13(3):7820–39.

Van Der Linden EL, Browne JL, Vissers KM, Antwi E, Agyepong IA, Grobbee DE, Klipstein-Grobusch K. Maternal body mass index and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A ghanaian cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(1):215–22.

Williams EA, Keenan KE, Ansong D, Simpson LM, Boakye I, Boaheng JM, Awuah D, Nkyi CA, Nyannor I, Arhin B, et al. The burden and correlates of hypertension in rural Ghana: a cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2013;7(3):123–8.

Wu F, Guo Y, Chatterji S, Zheng Y, Naidoo N, Jiang Y, Biritwum R, Yawson A, Minicuci N, Salinas-Rodriguez A, et al. Common risk factors for chronic non-communicable diseases among older adults in China, Ghana, Mexico, India, Russia and South Africa: the study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE) wave 1. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:88.

Agyei-Mensah S, de-Graft Aikins A. Epidemiological transition and the double burden of disease in Accra, Ghana. J Urban Health. 2010;87(5):879–97.

Bhutta ZA, Sommerfeld J, Lassi ZS, Salam RA, Das JK. Global burden, distribution, and interventions for infectious diseases of poverty. Infect Dis Poverty. 2014;3:21.

Remais JV, Zeng G, Li G, Tian L, Engelgau MM. Convergence of non-communicable and infectious diseases in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(1):221–7.

Rivera JA, Barquera S, Gonzalez-Cossio T, Olaiz G, Sepulveda J. Nutrition transition in Mexico and in other Latin American countries. Nutr Rev. 2004;62(7 Pt 2):S149–57.

Monteiro CA, Conde WL, Lu B, Popkin BM. Obesity and inequities in health in the developing world. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(9):1181–6.

Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(1):3–21.

Amuna P, Zotor FB. Epidemiological and nutrition transition in developing countries: impact on human health and development. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67(1):82–90.

Uauy R, Kain J, Mericq V, Rojas J, Corvalan C. Nutrition, child growth, and chronic disease prevention. Ann Med. 2008;40(1):11–20.

Popkin BM. The shift in stages of the nutrition transition in the developing world differs from past experiences! Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(1A):205–14.

Fernandez-Twinn DS, Ozanne SE. Mechanisms by which poor early growth programs type-2 diabetes, obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Physiol Behav. 2006;88(3):234–43.

Li D, Chen H, Ferber J, Odouli R. Infection and antibiotic use in infancy and risk of childhood obesity: a longitudinal birth cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;S2213-8587(16)30281–9.

McCormick B, Lang D. Diarrheal disease and enteric infections in LMIC communities: how big is the problem? Trop Dis Travel Med Vacc. 2016;2(11):1–7.

Salam RA, Das JK, Bhutta ZA. Current issues and priorities in childhood nutrition, growth, and infections. J Nutr. 2015;145(5):1116S–22S.

Lovejoy JC, Sainsbury A, Stock Conference Working G. Sex differences in obesity and the regulation of energy homeostasis. Obes Rev. 2009;10(2):154–67.

Micklesfield LK, Lambert EV, Hume DJ, Chantler S, Pienaar PR, Dickie K, Puoane T, Goedecke JH. Socio-cultural, environmental and behavioural determinants of obesity in black South African women. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2013;24(9–10):369–75.

Neupane S, Prakash KC, Doku DT. Overweight and obesity among women: analysis of demographic and health survey data from 32 Sub-Saharan African Countries. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:30.

Afrifa-Anane E, Agyemang C, Codjoe SN, Ogedegbe G, de-Graft Aikins A. The association of physical activity, body mass index and the blood pressure levels among urban poor youth in Accra, Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:269.

Aryeetey RN. Perceptions and Experiences of Overweight among Women in the Ga East District, Ghana. Front Nutr. 2016;3:13.

The Urban Transition in Ghana: urbanization, national development and poverty reduction. http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/G02540.pdf. Accessed 1 Aug 2016.

Amoah AG. Obesity in adult residents of Accra, Ghana. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(2 Suppl 2):S97–S101.

Agbeko M, Akwasi K, Druye A, Osei G. Predictors of overweight and obesity among women in Ghana. Open Obes J. 2013;5:72–81.

Pampel FC, Denney JT, Krueger PM. Obesity, SES, and economic development: a test of the reversal hypothesis. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(7):1073–81.

Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1107–17.

Omari R, Jongerden J, Essegbey G, Frempong G, Ruivenkamp G. Fast Food in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana: Characteristics, Availability and the Cuisine Concept. Food Stud: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2013;1(4):29–42.

Addo J, Agyemang C, Smeeth L, de-Graft Aikins A, Edusei AK, Ogedegbe O. A review of population-based studies on hypertension in Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2012;46(2 Suppl):4–11.

Bosu WK. Epidemic of hypertension in Ghana: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:418.

de-Graft Aikins A. Ghana’s neglected chronic disease epidemic: a developmental challenge. Ghana Med J. 2007;41(4):154–9.

Mendis S, Fuster V. National policies and strategies for noncommunicable diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6(11):723–7.

Mendis S. The policy agenda for prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. Br Med Bull. 2010;96:23–43.

Provo A. Towards Sustainable Nutrition for All Tackling the double burden of malnutrition in Africa. Sight Life. 2013;27(3):40–7.

Cline KM, Ferraro KF. Does Religion Increase the Prevalence and Incidence of Obesity in Adulthood? J Sci Study Relig. 2006;45(2):269–81.

Gonzalez-Casanova I, Sarmiento OL, Pratt M, Gazmararian JA, Martorell R, Cunningham SA, Stein A. Individual, family, and community predictors of overweight and obesity among colombian children and adolescents. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E134.

Phan K, Tian DH, Cao C, Black D, Yan TD. Systematic review and meta-analysis: techniques and a guide for the academic surgeon. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;4(2):112–22.

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

We declare that the data supporting the conclusions of this article are fully described within the article.

Authors’ contributions

RO and AAA contributed to study conception, literature search, data extraction and analysis as well as drafting major parts of the manuscript. AL drafted two sections of the manuscript, contributed to revisions and made important intellectual inputs. DB contributed to data extraction and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final submission.

Competing interests

The author declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

PRISMA Checklist. (DOC 64 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ofori-Asenso, R., Agyeman, A.A., Laar, A. et al. Overweight and obesity epidemic in Ghana—a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 16, 1239 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3901-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3901-4