Abstract

Background

Growing up with one parent is associated with economic hardship and health disadvantages, but there is limited evidence of its lifetime consequences. We examined whether being born to an unmarried mother is associated with socioeconomic position and marital history over the lifespan.

Methods

We analysed data from the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study including birth, child welfare clinic and school healthcare records from people born in Helsinki, Finland, between 1934 and 1944. Using a unique personal identification number, we linked these data to information on adult socioeconomic position from census data at 5-year intervals between 1970 and 2000, obtained from Statistics Finland.

Results

Compared to children of married mothers, children of unmarried mothers were more likely to have lower educational attainment and occupational status (odds ratio for basic vs. tertiary education 3.40; 95 % confidence interval 2.17 to 5.20; for lowest vs. highest occupational category 2.75; 1.92 to 3.95). They were also less likely to reach the highest income third in adulthood and more likely to stay unmarried themselves. The associations were also present when adjusted for childhood socioeconomic position.

Conclusion

Being born to an unmarried mother, in a society where marriage is the norm, is associated with socioeconomic disadvantage throughout life, over and above the disadvantage associated with childhood family occupational status. This disadvantage may in part mediate the association between low childhood socioeconomic position and health in later life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Growing up with one parent has become increasingly common for children in the Western world. From 1980s to 2008 the share of single parent families in Europe rose from 10 to 21 % mainly due cohabitations and divorces but there are demographic differences in single parenthood between European countries [1]. However, in Europe and elsewhere low socioeconomic position and poverty is more common in single parent households, especially those headed by a woman [2, 3].

The lifelong consequences of low childhood socioeconomic position (SEP) has been extensively studied [4, 5]. In most studies parents’ low occupational status has been used as an indicator of childhood SEP [6, 7], while markers indicating other aspects of potential early life deprivation, such as mother’s marital status, have been less frequently used. However, numerous studies show that single parent family background is highly relevant determinant of health at least among children and young adults, among whom it is associated with adverse physical and mental health outcomes [8–12] as well as poorer educational performance and idleness (being neither in school nor employed) [11–14]. Less is known about the effects of single parent background across the life course, because most of the previous studies are performed in relatively young cohorts. Those few studies that have focused on lifelong effects of single motherhood have indicated that at least men born outside of marriage have poorer health and higher mortality and they are more likely to stay unmarried or become divorced [15–18]. Some studies also suggest that people born out of wedlock attain lower adult socioeconomic position (SEP) than those born to a married mother [16, 17]. However, it is not clear how the lifelong consequences of being born to an unmarried mother are mediated through the other childhood socioeconomic factors, and results in these mediating associations are contradictory [10, 12, 19–23].

Further, in many studies single parent families are also seen as a homogenous group, although it includes children who grow up with a single parent from birth to adult life, and children born to an unmarried mother who later marries and the child grows up with two parents or caregivers. Less attention has been paid to outcomes among different subgroups such as children born out of wedlock. Thus, a recent review concluded that research has not distinguished out of wedlock birth from single parenthood in general and called studies focusing on outcomes in different subgroups [13].

The main objective of this study was to examine whether being born out of wedlock in a society where marriage was the norm is associated with socioeconomic position and marital status in later life. The secondary objectives were to assess whether these associations are mediated through perinatal and childhood factors associated with being born to an unmarried mother and whether they are specific to children with no indication of a male caregiver rather than those who later had a male caregiver. In measuring socioeconomic position in adulthood we used different indicators of SEP from several time points across adult life.

Methods

This study is a part of the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study (HBCS), which includes 13345 people born in either of the two public maternity hospitals from 1934 to 1944. The HBCS has been described in detail [24] and has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Public Health Institute. Register data were linked with permissions from Statistics Finland and the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Early life data came from birth, child welfare clinic and school healthcare records.

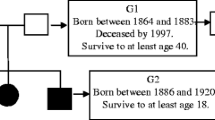

Mother’s marital status

We defined mother’s marital status, as married or unmarried, when giving birth. The subgroups of the study are illustrated in the Fig. 1. Most married mothers (n = 12635) were classified based on information on the mother’s current last name and maiden name, as at that time women were by law required to adopt their husband’s last name when married. They also had an entry at least in one of the following sections: mother’s occupation when married, father’s occupation or father’s name. In the married group we also included 9 women who had a different last name in the birth record but who had no ‘unmarried’ entry and had obtained their husband’s name according to other records.

Most unmarried mothers (n = 531) were identified based on an entry ‘unmarried’ in the birth record. 107 mothers had no entry in the marital status section and five mothers had unclear entries in the name sections but neither group had any indication of the child’s father in the records. Thus, they were identified as unmarried. In addition, 22 women were widows and 17 divorced according to the birth record. Six mothers had died either in delivery or later according to the child welfare clinic or school records, and in 13 further cases we were unable to determine the mother’s marital status because of unclear entries. These 58 cases (0.4 %) were excluded from the analyses. Furthermore, we also excluded 32 married mothers with no information on the male caregiver’s occupation and 6 unmarried mothers with no information on the mother’s occupation. In our final analyses we included 6921 (52,2 %) male and 6328 (47,8 %) female offspring, in total 13249 people.

We have no data that would systematically indicate whether the parents were divorced or the father died later on. In a subset of 1658 subjects of the cohort, 28 (1.7 %) indicated that their father had died in the war [25]. This number is small and death from other reasons and divorce were rare at that time. Therefore, we have included these subjects in the analysis.

Historical context

In the interwar period in Finland almost 10 % of babies were born ”illegitimate”, as they were referred to at that time. At the same time unmarried motherhood became more problematic when paid work outside home became more common for women and moral values underlined family values. Unmarried mothers were usually women from lower social classes [26]. The 1934–1944 period, during which our cohort was born, represents a period of transition in Helsinki. Philanthropically organized child welfare clinics offered guidance in child care and child welfare developed, in part to combat the increased mortality of “illegitimate” children. However, this time period also includes World War II, during which Finland fought two wars against the Soviet Union.

Other variables

The HBCS also includes information on living conditions in childhood. As descriptive characteristics, we present the number of rooms and people living in the same childhood household (Table 1), obtained from the child welfare clinic record. As a covariate in our analyses we used information on 1770 children (13.4 %) who were evacuated unaccompanied by their parents to temporary foster homes in Sweden or Denmark during World War II. These children have poorer health and lower SEP in adult life [27, 28].

Early life socioeconomic position

We defined childhood SEP based on the mother’s and father’s (or other male caregiver’s) highest occupational status as indicated in birth, childhood welfare clinic and school records. We classified the mothers’ occupational information according to the 1980 Classification of Occupations by Statistics Finland [29]. We used a 9-level socioeconomic coding (1 = employers, 2 = self-employed, 3 = senior clericals, 4 = junior clericals, 5 = manual workers, 6 = pensioners, 7 = students and pupils, 9 = unknown occupation/information missing). There were no pensioners among the subjects, and values indicating students and pupils and unknown occupations were set as missing. Using the highest category of the four time points (occupation before and during marriage in birth records, and current occupation in child welfare clinic and school records), we divided occupations into two categories: middle class (categories 1 to 4) and workers (category 5). Occupational information was available for 11819 mothers (89.2 %) (Table 1). Male caregivers’ occupational information was available for 12946 of the male caregivers and has been classified earlier using the same classification (97.7 %) [27].

We combined male caregiver’s prospective occupational information with mother’s marital status by dummy variables indicating both categories, with mothers married to manual worker male caregivers as a reference category. We performed these analyses in two ways: not adjusting and adjusting for mother’s occupational status (worker/middle class).

Socioeconomic position in late life

Using a personal identification number, we linked early life data to information on adult educational attainment, occupational status, income and marital status, obtained from Statistics Finland at 5-year intervals between 1970 and 2000. We grouped maximum achieved occupation into four categories (1 = manual workers; 2 = self-employed; 3 = low official; 4 = high official) [30]. Education was grouped into four categories (1 = Basic or less or unknown, 2 = Upper secondary, 3 = Lower tertiary, and 4 = Higher tertiary) [31]. Income information is based on state taxation from the same period. Taxable incomes were first log-transformed, and the data were standardised separately at each data collection point by sex. Participants who were recorded as retired at a specific data collection point were not included in the standardisation at that point. Maximum income level during adulthood was defined by using standardised values and split into thirds (1 = lowest, 2 = intermediate, 3 = highest).

In total, 12304 men and women had information on their marital status at 5 year intervals between 1970 and 2000. We split these into two groups: ever married (entry “married”, “divorced” or “widowed” at any of the time points)/never married (none of these entries at any time point) and ever divorced (entry “divorced” at any of the time points)/never divorced (entry “single”, “married” or “widowed” at any time points but no entry “divorced”).

Analysis

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the birth characteristics for people born to unmarried mothers and people born married mothers. The associations between mother’s marital status and offspring’s SEP and marital status in adulthood were analysed using multinomial logistic regression analysis with three models. The first model included year of birth and sex). The second included, in addition, perinatal and childhood factors associated with being born to an unmarried mother: birth weight, birth order, mother’s age, length of gestation and evacuation abroad without parents during World War II [25, 28]. While these factors could strictly be considered to be on the causal pathway between being born to an unmarried mother and the outcomes, we include these in this and consequent models to illustrate to what extent the associations with being born to an unmarried mother are independent of these perinatal and childhood factors. Associations of these variables with outcomes are presented in Table 2. The third model also included mother’s occupational information as another indicator of childhood SEP. We also tested if any of these associations were moderated by sex by including an interaction term ‘mother’s marital status in childhood * sex’ in the regression. In addition, we tested associations between different types of families (by mother’s marital status and the presence and occupational status of the male caregiver) and adulthood outcomes. These analyses were controlled for the same variables as in the second model and also included a dummy variable representing mother’s marital status at birth and male caregiver’s highest occupational status during childhood. We also present these models controlled for mother’s occupation.

Results

Maternal and neonatal characteristics are shown in Table 1. Unmarried mothers were on average younger, shorter and had a lower body mass index in late pregnancy. They also had a lower occupational status than married women. Their offspring were on average lighter and shorter than children born to married mothers, they were born at an earlier gestational age and were more often firstborn. In families of unmarried mothers who later had a male caregiver, the male caregiver had on average a lower occupational status than male caregivers in families of married mothers. This difference was less strong than the difference in occupational status between unmarried and married mothers.

Table 3 presents odds ratios (ORs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) from the multinomial logistic regression predicting the highest educational attainment, occupational status and maximum income in adulthood according to mother’s marital status at the time of birth. Compared to children of married mothers, children of unmarried mothers were more likely to have lower educational and occupational levels and income as adults. The associations were graded, so that the ORs increased with decreasing educational, occupational and income categories. They were little changed after adjusting for year of birth, sex, birth order, mother’s age, length of gestation and wartime evacuation status. Further adjustments with mother’s height and body mass index in late pregnancy attenuated the associations slightly (data not shown). In addition, after adjusting for mother’s occupational status the associations were somewhat attenuated, although most remained statistically significant. All associations were similar in men and women (p-values for interaction sex * unmarried mother >0.05).

We then compared different types of families based on mother’s marital status at birth and later presence of a male caregiver and his occupational status. As a reference group we used children who were born to married mothers and whose fathers/male caregivers were manual workers. Compared with these children, children born to an unmarried mother who had no male caregiver during childhood had the highest chance of ending up in the lower SEP groups in adulthood (Tables 4, 5 and 6). Also children born to unmarried mothers who later had a manual worker male caregiver were more likely to attain a lower adult SEP than corresponding children born to married mothers. The tables show that children who had an unmarried mother and who later had a male caregiver in a middle class profession had similar SEP prospects as the reference group of children of married mothers and manual worker fathers. However, these children attained a lower SEP than children of married mothers whose fathers had a middle class profession. After adjusting for mother’s occupational status the ORs attenuated a little). In other words, having a mother in a middle class profession, regardless of whether the child was born to a married or unmarried mother, seemed to increase the possibility of reaching a higher SEP in adulthood.

Children born to unmarried mothers were more likely to stay unmarried in adulthood compared with children of married mothers (Table 7). Again, the group with the highest odds comprised children born to an unmarried mother with no male caregiver during childhood. In analyses related to marital status in adulthood, we found no difference between any other family groups (Table 8). Children of unmarried mothers who ended up married in adulthood had a similar chance of divorce than those of married mothers.

Discussion

We examined how mother’s marital status when giving birth was associated with offspring’s lifetime SEP and marital status. Our results showed that children born out of wedlock almost 80 years ago attained a lower SEP in adulthood and were more likely to remain unmarried than children of married mothers. The most disadvantaged group consisted of children born to an unmarried mother who did not have a male caregiver during childhood years. They were most likely to end up in lower SEP and to stay unmarried. Also children who were born to an unmarried mother and who later had a male caregiver attained a lower SEP than those born to married mothers. Furthermore, having a mother with a middle class profession increased the offspring’s probability of reaching a higher SEP in adulthood independently of mother’s marital status at birth.

Previous studies have reported an association between single parent background and lower SEP in later life [12, 14, 16, 17] but there are also studies showing no association after childhood socioeconomic circumstances are accounted for [21, 23]. However, the majority of this previous research has focused on outcomes in early adulthood [12, 22, 32, 33] and treated divorced, separated, never married as well as widowed, as if they were a homogeneous single parent group [21, 33–35]. Fewer studies have focused only on children born out of wedlock and measured changes in SEP in later life [16, 17]. This kind of a study design has been used in a small number of studies from Sweden [16] and Denmark [17]. These studies have reported associations between out of wedlock birth and later life outcomes, including SEP as well as health, largely independent of childhood socioeconomic circumstances. Our results are in line with these studies. We found that out of wedlock birth was associated with worse SEP in adulthood according to all indicators. The associations we found, were not explained through socioeconomic circumstances in childhood even though mother’s occupation at birth, as a marker of childhood socioeconomic position, was positively related to the likelihood that a child would attain a higher SEP in adulthood. Previous Scandinavian studies have also reported that men, but not women, born out of wedlock tend to more often become widowers, experience divorce and stay unmarried themselves [15–17]. In the present study this association between out of wedlock birth and the tendency to stay unmarried was found among both sexes. However, we found no association between out of wedlock birth and experiencing of divorce.

Our study adds to this previous literature by showing that the long-term effects of single parent background remained, in both sexes, even when adulthood SEP was measured several times during adult life and was observed by using three different indicators of SEP.

Several mechanisms could explain these associations. First, being born to an unmarried mother may have meant a lack of material resources, for example food, during the foetal period and throughout childhood. Intrauterine growth, for which size at birth in relation to gestational age serves as a marker, has an important role for the development of vital organs such as the brain and may have long-term consequences for later development [36, 37]. Second, the social stigma experienced by children born out of wedlock may have lead to stress [11, 13] and have an impact on their upbringing, self-identity and which may subsequently translate to later life consequences including SEP. From an evolutionary perspective, investments made for a child can differ greatly between single parent and two parent families. In two parent families both parents usually have more resources, e.g. income, time and attention, while a single parent may have to focus much of the social and material resources on earning a livelihood and possibly combating social stigma [11, 12, 38, 39]. If a single mother later is married it may improve children’s standard of living although relationships in stepfamilies may be tense [11, 40].

The strong associations between mother’s marital status and offspring SEP in adulthood we found are likely to contribute to the association between low childhood SEP and health in later life. However, our data also show that many people born to an unmarried mother gain a good education and occupation despite early disadvantage. Moreover, it is important to highlight that in any study out of wedlock birth should be understood as an indicator of social disadvantage in the specific historical context of the study period. Our cohort members were born between 1934 and 1944 during an era when marriage was the norm. Therefore no direct analogy can be drawn to birth outside marriage and single parenting in contemporary societies. There are, however, still many contemporary contexts, where single mothers may have limited material and social resources similarly to participants of the present study.

Our results deserve an additional note from a technical perspective. Father’s occupational status is a widely used indicator of childhood SEP in epidemiological studies. It is important to realise that a missing father’s occupation may indicate a child born to an unmarried mother. In such cases it may be wiser to include such children as a separate category rather than to exclude them because of missing data, assess SES by the single parent’s occupation, or to use a purely statistical imputation technique. The limitations of the HBCS have been discussed [41]. Data on marital status, SEP and birth characteristics came from reliable records. While SEP in childhood was based only on occupational information, we have used both the mother’s and possible male caregiver’s occupations and classified occupational status based on modern standards of classifying historical occupational data. We have no data, however, on the remaining family members other than their number. Moreover, the adult occupational data are available from year 1970 onwards, when the cohort members were aged 26–36 years, precluding the assessment of socio-economic trajectories in adult life. We have no data on cohabitation without marriage. This is unlikely to be a major limitation for our main exposure, as marriage was the norm when the study participants were born, but constitutes a limitation for marital status as an outcome. Our study population may not be representative of all people living in Helsinki at that time. However, the distribution of occupational categories is consistent with the general occupational distribution in Helsinki 80 years ago among married HBCS families [42]. Child welfare clinic services were voluntary and free of charge and our data indicate that these clinics were attended by children from all socioeconomic groups. It is also possible that some unmarried mothers were recorded as married in the records and thus the married group may include a proportion of “false negatives”. This would be expected, if anything, to reduce the differences between children of married and unmarried mothers.

Conclusion

This life course study shows that children born out of wedlock carry a socioeconomic disadvantage throughout life. As compared with children born to married mothers, they have approximately three-fold odds of ending up in the lowest than in the highest educational and occupational categories. Most likely to end up in these categories are children born to unmarried mothers who have no male caregiver during childhood. These associations are not explained by other socioeconomic factors as indicated by mother’s and possible male caregiver’s occupational statuses. This disadvantage starting in early life is likely to have a substantial effect on lifetime health.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- HBCS:

-

the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- SEP:

-

Socioeconomic Position

References

Jokinen K, Kuronen M. Research on families and family policies in Europe - major trends. In: Uhlendorff U, Rupp M, Euteneuer M, editors. Wellbeing of families in future Europe - challenges for research and policy. FAMILYPLATFORM families in Europe volume 1. 2011. p. 13–118. http://europa.eu/epic/docs/family_platform_book1.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2016.

Brodolini Foundation G. Study on poverty and social exclusion among lone parent households. Report prepared for the European commission. Brussels: European Commission; 2007. http://ec.europa.eu/employment_social/social_inclusion/docs/2007/study_lone_parents_en.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2016.

Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America's children: Key national indicators of well-being, 2015. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2015. http://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/index.asp. Accessed 1 Mar 2016.

Kuh D, Hardy R, Langenberg C, Richards M, Wadsworth ME. Mortality in adults aged 26–54 years related to socioeconomic conditions in childhood and adulthood: post war birth cohort study. BMJ. 2002;325:1076–80.

Power C, Stansfeld SA, Matthews S, Manor O, Hope S. Childhood and adulthood risk factors for socio-economic differentials in psychological distress: evidence from the 1958 British birth cohort. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:1989–2004.

Poulton R, Caspi A, Milne BJ, Thomson WM, Taylor A, Sears MR, Moffitt TE. Association between children's experience of socioeconomic disadvantage and adult health: a life-course study. Lancet. 2002;360:1640–5.

Smith GD, Hart C, Blane D, Hole D. Adverse socioeconomic conditions in childhood and cause specific adult mortality: prospective observational study. BMJ. 1998;316:1631–5.

Krueger PM, Jutte DP, Franzini L, Elo I, Hayward MD. Family structure and multiple domains of child well-being in the United States: a cross-sectional study. Popul Health Metr. 2015. doi:10.1186/s12963-015-0038-0.

Sauvola A, Mäkikyrö T, Jokelainen J, Joukamaa M, Järvelin MR, Isohanni M. Single-parent family background and physical illness in adulthood: a follow-up study of the Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort. Scand J Public Health. 2000;28:95–101.

Weitoft GR, Hjern A, Haglund B, Rosén M. Mortality, severe morbidity, and injury in children living with single parents in Sweden: a population-based study. Lancet. 2003;361:289–95.

Amato PR. The impact of family formation change on the cognitive, social, and emotional well-being of the next generation. Future Child. 2005;15:75–96.

McLanahan S, Sandefur G. Growing up with a single parent: what hurts, what helps. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1994.

Brown S. Marriage and child well-being: research and policy perspectives. J Marriage Fam. 2010;72:1059–77.

Martin MA. Family structure and the intergenerational transmission of educational advantage. Soc Sci Res. 2012;41:33–47.

Vågerö D, Modin B. Prenatal growth, subsequent marital status, and mortality: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2002;324:398.

Modin B, Koupil I, Vågerö D. The impact of early twentieth century illegitimacy across three generations. Longevity and intergenerational health correlates. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1633–40.

Lund R, Christensen U, Holstein BE, Due P, Osler M. Influence of marital history over two and three generations on early death. A longitudinal study of Danish men born in 1953. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:496–501.

Juarez SP, Goodman A, Koupil I. From cradle to grave: tracking socioeconomic inequalities in mortality in a cohort of 11 868 men and women born in Uppsala, Sweden, 1915–1929. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016. doi:10.1136/jech-2015-206547.

Sauvola A, Räsänen PK, Joukamaa MI, Jokelainen J, Järvelin MR, Isohanni MK. Mortality of young adults in relation to single-parent family background. A prospective study of the Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort. Eur J Public Health. 2001;11:284–6.

Scharte M, Bolte G, for the GME Study Group. Increased health risks of children with single mothers: the impact of socio-economic and environmental factors. Eur J Public Health. 2012. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cks062.

Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to single parenthood in childhood and later mental health, educational, economic, and criminal behavior outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1089–95.

Seabrook JA, Avison WR. Family structure and Children's socioeconomic attainment: a Canadian sample. Can Rev Sociol. 2015. doi:10.1111/cars.12061.

McMunn AM, Nazroo JY, Marmot MG, Boreham R, Goodman R. Children's emotional and behavioural well-being and the family environment: findings from the Health Survey for England. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:423–40.

Osmond C, Kajantie E, Forsén TJ, Eriksson JG, Barker DJ. Infant growth and stroke in adult life: the Helsinki birth cohort study. Stroke. 2007;38:264–70.

Pesonen AK, Räikkönen K, Heinonen K, Kajantie E, Forsén T, Eriksson JG. Depressive symptoms in adults separated from their parents as children: a natural experiment during World War II. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:1126–33.

Vågerö D, Koupilova I, Leon DA, Lithell UB. Social determinants of birthweight, ponderal index and gestational age in Sweden in the 1920s and the 1980s. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:445–53.

Pesonen AK, Räikkönen K, Kajantie E, Heinonen K, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Forsén T, Eriksson JG. Inter-generational social mobility following early life stress. Ann Med. 2011;43:320–8.

Alastalo H, Räikkönen K, Pesonen AK, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Kajantie E, Heinonen K, Forsén TJ, Eriksson JG. Cardiovascular health of Finnish war evacuees 60 years later. Ann Med. 2009;41:66–72.

Statistics Finland. Classification of occupations. Helsinki: Statistics Finland. Handbooks / Statistics Finland; 1980. p. 14.

Statistics Finland. Classification of socio-economic groups. Helsinki: Statistics Finland; 1989. Handbooks / Statistics Finland, 17 (in Finnish, English summary). http://www.stat.fi/meta/luokitukset/sosioekon_asema/001-1989/kasikirja.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2016.

UNESCO. International Standart Classification of Education ISCED 1997. http://www.unesco.org/education/information/nfsunesco/doc/isced_1997.htm. Accessed 1 Mar 2016.

Aquilino WS. The life course of children born to unmarried mothers: childhood living arrangements and young adult outcomes. J Marriage Fam. 1996;58:293–310.

Spencer N. Does material disadvantage explain the increased risk of adverse health, educational, and behavioural outcomes among children in lone parent households in Britain? A cross sectional study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:152–7.

Dunifon R. Who's in the house? race differences in cohabitation, single parenthood, and child development. Child Dev. 2002;73:1249–64.

Montgomery LE, Kiely JL, Pappas G. The effects of poverty, race, and family structure on US children's health: data from the NHIS, 1978 through 1980 and 1989 through 1991. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1401–5.

Barker DJP. Mothers, babies and health in later life. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998.

Räikkönen K, Pesonen AK, Roseboom TJ, Eriksson JG. Early determinants of mental health. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26:599–611.

Thomson E. Family structure and child well-being: economic resources vs parental behaviors. Soc Forces. 1994;73:221–42.

Amato PR. Single-parent households and children's educational achievement: A state-level analysis. Soc Sci Res. 2015. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.05.012.

Hanson TL. Double jeopardy: parental conflict and stepfamily outcomes for children. J Marriage Fam. 1996;8:141–54.

Barker DJ, Osmond C, Forsén TJ, Kajantie E, Eriksson JG. Trajectories of growth among children who have coronary events as adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1802–9.

Siipi J. Pääkaupunkiyhteiskunta ja sen sosiaalipolitiikka. In: Rosen R, Hornborg E, Jutikkala E, Waris H, Castren MJ, editors. Helsingin kaupungin historia. 5. osa, 1. nide, ajanjakso 1918–1945. Helsinki: Helsingin kaupunki; 1962. p. 137.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Academy of Finland; The Doctoral Programme in Population Health; Emil Aaltonen Foundation; Finnish Foundation for Pediatric Research; Finnish Special Governmental Subsidary for Health Sciences (evo); Juho Vainio Foundation; Medical Societies of Finland (Duodecim and Finska Läkaresällskapet); Novo Nordisk Foundation; Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation; Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation; Sigrid Jusélius Foundation; and Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation. No funding source had any role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the articles; or in the decision to submit it for publication.

Availability of data and materials

Due to grounds of confidentiality and anonymity, requests for data should be directed to the principal investigator or the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study, Professor Johan Eriksson (johan.eriksson@helsinki.fi). The authors welcome collaboration, but data requests may be subject to further review by an Ethics committee and/or relevant register authority.

Authors’ contributions

MM conceptualized the present study, consolidated and analyzed data, wrote the first draft of the paper and coordinated other authors’ contributions. MKS consolidated data, participated in data analysis and contributed to redrafts. AH is an expert in social history, took part in the interpretation of data and contributed to redrafts. MO coordinated other authors’ contributions, took part in the interpretation of data and contributed to redrafts. AKP and KR are experts in early life programming of mental health took part in the interpretation of data and contributed to redrafts. CO performed data analysis and contributed to redrafts. JGE initiated the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study, collected data, and contributed to redrafts. EK planned the present study together with MM, collected data, coordinated other authors’ efforts and contributed to redrafts of the paper. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Helsinki Birth Cohort study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Public Health Institute. Register data were linked with permissions from Statistics Finland and the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before any study procedure was initiated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mikkonen, H.M., Salonen, M.K., Häkkinen, A. et al. The lifelong socioeconomic disadvantage of single-mother background - the Helsinki Birth Cohort study 1934–1944. BMC Public Health 16, 817 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3485-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3485-z