Abstract

Background

Previous studies have stressed the importance of tobacco exposure for the mood disorders of depression and anxiety. Although a few studies have focused on perinatal women, none have specifically considered the effects of smoking and secondhand smoke exposure on perinatal suicidal ideation. Thus, this study aimed to investigate the relationships of smoking/secondhand smoke exposure status with suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety from the first trimester to the first month post partum.

Methods

This cross-sectional study based on self-reported data was conducted at five hospitals in Taipei, Taiwan from July 2011 to June 2014. The questionnaire inquired about women’s pregnancy history, sociodemographic information, and pre-pregnancy smoking and secondhand smoke exposure status, and assessed their suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety symptoms. Logistic regression models were used for analysis.

Results

In the 3867 women in the study, secondhand smoke exposure was positively associated with perinatal depression and suicidal ideation. Compared with women without perinatal secondhand smoke exposure, women exposed to secondhand smoke independently exhibited higher risks for suicidal ideation during the second trimester (odds ratio (OR) = 7.63; 95 % confidence interval (CI) = 3.25–17.93) and third trimester (OR = 4.03; 95 % CI = 1.76–9.23). Women exposed to secondhand smoke had an increased risk of depression, especially those aged 26–35 years (OR = 1.71; 95 % CI = 1.27–2.29).

Conclusions

Secondhand smoke exposure also considerably contributes to adverse mental health for women in perinatal periods, especially for the severe outcome of suicidal ideation. Our results strongly support the importance of propagating smoke-free environments to protect the health of perinatal women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tobacco smoking is a major concern because of its harm to human health, especially that of perinatal women. Both active and passive smoking during pregnancy have been associated with negative impacts on maternal and infant health, including stillbirths, preterm deliveries, low birth weight, and neonatal death [1–5]. However, even during pregnancy, the husbands of more than half of women have a smoking habit [6]. Furthermore, 6.2 and 54.6 % of people are frequently exposed to secondhand smoke in indoor and outdoor public areas, respectively [7]. This means that women have a high chance of being exposed to a secondhand smoke environment.

Emotional disturbance is a crucial health consideration, especially during the perinatal period. The development of depression or anxiety is often preceded by specific or chronic life stressors (eg, pregnancy and motherhood in the case of perinatal women). Empirical studies have suggested that between 15 and 25 % of pregnant women experience anxiety or depression [8]. Indeed, women experience substantial hormonal and physiological changes during pregnancy. It was reported that the functioning of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, which is key to stress response, changes dramatically during pregnancy, largely because of the influence of the placenta [9]. As pregnancy progresses, placental production of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) increases exponentially [10]. CRH has been proposed as being involved in the pathophysiological response of the HPA axis in mental pathologies such as depression [11, 12].

Both depression and anxiety have been found to be significantly related to smoking [13–15]. Prospective cohort and case–control studies have also reported significant evidence that smoking is associated with all forms of suicidality [16–18]. Studies have also determined that secondhand smoke exposure is positively associated with depressive symptoms [19, 20]. However, the relationship between anxiety and secondhand smoke exposure was less consistent [21]. Indeed, either through active or passive smoking, exposure to various psychoactive compounds of tobacco smoke may contribute to the dysregulation of affective states [22]. For example, nicotine may affect numerous neurotransmitters to influence the pathophysiology of depression [23] through the activation or desensitization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) [24, 25]. Along with facilitating cholinergic neurotransmission, nAChRs affect the activities of the neuroendocrine system and are thus involved in depression and the HPA axis [26]. Specifically for nonsmokers, secondhand smoke exposure may lead to lower levels of dopamine and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which have been related to an increased risk for mental disorder [27].

Most studies of perinatal women that have discussed smoking and secondhand smoke exposure have focused on the physical damage to the women and their children [28–31]. Several studies have found that pregnant women who were smokers or had quit after pregnancy were more likely to report depressive symptoms and anxiety disorders [32–35]. Few studies have investigated the link between smoking and suicidal behavior for postnatal women. Among those that have, Tavares et al. in 2012 found nonsignificant differences between smoking and suicidal behavior after adjusting for sociodemographics (eg, age and education), psychosocial factors (eg, social support and stressful events), and comorbidities of depression and anxiety disorder [36]. No study has specifically investigated the association between secondhand smoke exposure and suicidality among perinatal women.

A large body of literature relates to perinatal psychopathology, including depressive symptoms [37, 38], anxiety [39, 40], and suicidality [41, 42], with the effects of a history of depression before pregnancy being a frequent topic [43]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no researchers have simultaneously considered the effects of smoking and secondhand smoke exposure on perinatal suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety. Furthermore, the associations have not been carefully examined during the pregnancy-to-postpartum periods.

The perinatal period encompasses the first trimester to the postpartum phase, with each constituent period marked by specific maternal mental and physical changes, fetal developments, and subsequent various clinical and practical implications regarding antenatal care and interventions [44]. Indeed, women in each trimester of pregnancy would experience various physical and mental symptoms. For example, at the earlier stage, mothers with syndromes of nausea and vomiting, the most common physical discomforts during the first trimester [45], may be more sensitive to tobacco exposure. Mental ailments are likely to increase as the pregnancy moves towards the third trimester [46]. During postnatal periods, mothers may display more emotional disturbances under tobacco exposure due to concerns of its impact on their infant’s health. Investigating variation of emotional symptoms at different periods of time may thus facilitate the design and implementation of intervention and health education programs at the most suitable times.

Thus, in this study, we investigated the relationships of smoking/secondhand smoke exposure status with suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety from the first trimester to the first month post partum. Specifically, this study aimed to (1) examine the occurrence of suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety in pregnant women from the prenatal to postpartum periods; (2) investigate the risks of suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety among perinatal women who are exposed to tobacco, including pre-pregnancy smoking and secondhand smoke; and (3) explore whether associations between women’s exposure to tobacco and risks for suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety differed according to the women’s characteristics.

Methods

Participants and procedures

This cross-sectional study was conducted in five hospitals in Taipei City and New Taipei City, Taiwan. The hospitals were a part of major obstetric hospitals in Northern Taiwan and were selected according to their willingness to participate in this perinatal mental health program. Between July 2011 and June 2014, pregnant women and women within 1 month post partum who had received outpatient service at one of the hospitals were consecutively approached and invited to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were (1) being unable to read or write Chinese and (2) having a severe psychiatric illness (ie, being clinically diagnosed with bipolar disorder, nonaffective psychosis (such as schizophrenia), or substance use disorder).

Interviewers were trained for standardization. The interviewers approached potential participants and explained to them the study and the content of the consent form. After providing informed consent, the participants spent approximately 15 min completing the questionnaire at the outpatient center, with an overall response rate of 75 %. The self-reported questionnaire inquired about the participants’ pregnancy history, sociodemographic information, and smoke and secondhand smoke exposure status, and assessed their suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety symptoms.

Measures

Smoking and secondhand smoke status

We attempted to collect information on tobacco smoking during pregnancy. However, the number of reported prenatal smokers was too low for further analysis because smoking during pregnancy is a violation of Taiwanese law. Accordingly, we only used pre-pregnancy smoking status (which women were more comfortable to report accurately) to estimate the association between smoking behavior and mood disorders. Pre-pregnancy smoking status was assessed using the following questions: “Have you smoked more than 100 cigarettes over your entire life?” If the answer was “yes,” then the participant was asked, “How many cigarettes per day did you smoke immediately before your pregnancy?” If the answer was more than one cigarette per day, then the participant was identified as a pre-pregnancy smoker [47].

Secondhand smoke exposure status was assessed using the question: “Does anyone smoke around you in your home or workplace?” If the answer was “always” or “usually,” then the participant was identified as having “high secondhand smoke exposure.” If the answer was “sometimes” or “never,” then the participant was identified as having “low secondhand smoke exposure.”

Depression and anxiety

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was used to assess symptoms of depression in the participants. The EPDS has been reported to efficiently screen for depression in women during the pregnancy and postnatal periods [48, 49]. The EPDS consists of ten items that assess how participants have been feeling in the past 7 days. The total EPDS score is calculated by summing participant responses; scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores reflecting a greater level of depressive symptoms. In this study, EPDS scores of >13 were identified as indicating depression [48, 50]. The Chinese version of the EPDS has exhibited strong reliability and validity [51, 52].

Anxiety was assessed using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [53]. The STAI is a 20-item questionnaire with total scores ranging from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating a higher level of anxiety. In this study, a total STAI score of >60 was identified as indicating anxiety [54]. The Chinese version of the STAI exhibited strong reliability and validity [55].

Suicidal ideation

Similar to previous studies, suicidal ideation was defined as an answer of “sometimes” or “yes, quite often” to question 10 of the EPDS: “The thought of harming myself has occurred to me.” “No suicidal ideation” was defined by answering “hardly ever” or “never” to question 10 [56].

Other covariates

Other covariates that were reported as being associated with smoking and mood disorders were recruited for further consideration, namely peripartum period (first trimester, second trimester, third trimester, and first month post partum), age group (<25, 26–35, and >36 years), marital status (married vs. other), monthly income (<NT$30,000, NT$30,000–100,000, and > NT$100,000), employment status (yes vs. no), educational level (<12, 12–15, >15 years of education), body mass index (BMI) [57], birth order (primipara vs. multipara), baby sex (male, female, or unknown), agreement with the expectation of fetus sex (inconsistent vs. other (including consistency, no specific expectation, and unknown sex) [58], planned pregnancy (yes vs. no), and a history of depression prior to pregnancy (yes vs. no) [35]. The participants who responded to the question “How was your quality of sleep during the past 7 days?” with “very good,” “good,” or “normal” were identified as not having sleep problems. Those who answered “bad” or “very bad” were identified as having sleep problems.

Statistical analysis

All available demographic measures were considered in the analysis. The occurrence of suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety were calculated separately for the four perinatal periods including the first to third trimesters during pregnancy and 1 month post partum. Associations of smoking and secondhand smoke exposure status with each dependent variable of suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety were assessed through chi-squared tests.

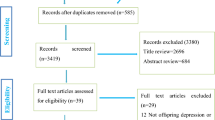

A univariate logistic regression was performed as the first step to estimate the risks of suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety associated with smoking and secondhand smoke exposure status. Variables which may possibly be associated with dependent variables (p < 0.1) were further considered in multivariate logistic regression models, with odds ratios (ORs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) estimated. Factors such as BMI, birth order, the baby’s sex, and agreement with the expectation of the baby’s sex that did not display significant effects were not included in the final model for estimation. In addition, the potential modifying effects of demographic factors were considered. Subgroup analyses and models were applied if the interaction terms of the secondhand smoking status and demographic factors were associated with the dependent variables (p < 0.2). In the suicidal ideation model, a significant interaction existed between secondhand smoke exposure status and perinatal period. In the depression model, a significant interaction existed between secondhand smoke exposure status and age group. No other variables showed significant modifying effects.

The significance level for all statistical analyses was p < 0.05. All data were analyzed using statistical software of SAS version 9.3 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

In total, 3867 participants completed the questionnaire. Table 1 presents the sample characteristics. Approximately three-fourths of the women were in the second (34.83 %) and third trimesters (40.35 %). Most of the participants were 26–35 years old (73.93 %), employed (76.92 %), married (97.07 %), had a monthly income of NT$30,000–NT$100,000 (63.61 %), and had been educated for >12 years (86.03 %). Approximately 60 % of the sample were primipara.

Figure 1 presents the suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety during the four perinatal periods. More women reported depression than other outcomes of anxiety and suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation increased with time (0.85–4.03 %) and was higher in the postpartum period. The highest occurrences observed for suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety were during 1 month post partum.

Table 2 shows that the women who had high secondhand smoke exposure were more likely to have suicidal ideation and depression (p < 0.001) but not anxiety. Regarding pre-pregnancy smoking status, the women who were pre-pregnancy smokers were more likely to have suicidal ideation (p = 0.0032) but not depression or anxiety.

Suicidal ideation

The effect of secondhand smoke exposure on suicidal ideation was statistically significant. After adjustment for perinatal period, age, marital status, monthly income, employment status, educational level, planned pregnancy, history of depression, and sleep quality, the OR for suicidal ideation for the women who had high secondhand smoke exposure was 2.5 (95 % CI = 1.30–4.82) (see Additional file 1). In the multivariate analysis, we found that women who were younger, had a history of depression, or were not sleeping well were significantly more likely to have suicidal ideation.

To further explore potential effects by different perinatal periods, a subgroup analysis and models were performed for each time period (Table 3). The effect of secondhand smoke exposure on suicidal ideation was significant in the second (OR = 7.63; 95 % CI = 3.25–17.93) and third trimesters (OR = 4.03; 95 % CI = 1.76–9.23). This means that pregnant women during the second or third trimesters who were frequently exposed to secondhand smoke had an increased risk of suicidal ideation. The model in the postpartum period was unavailable because no participant with high secondhand smoke exposure reported suicidal ideation.

Depression

Exposure to secondhand smoke was also associated with depression. After adjustment for other covariates, the OR for depression among the women who had high secondhand smoke exposure was 1.55 (95 % CI = 1.20–2.01) (see Additional file 1). In the multivariate analysis, we determined that women who were unmarried, had a lower income, had an unplanned pregnancy, had a history of depression, or were not sleeping well were significantly more likely to have depression.

The interaction effect of age and secondhand smoking was significant (p = 0.02). To further explore the potential modifying effects in different age groups, a subgroup analysis and models were applied for each age group (Table 3). The effect of secondhand smoke was only significantly associated with depression in women aged 26–35 years (OR = 1.71; 95 % CI = 1.27–2.29).

Anxiety

We found no significant association between secondhand smoke and anxiety (see Additional file 1). However, in the multivariate analysis, we observed that postpartum women and women who had a lower education level were significantly more likely to report higher levels of anxiety.

Discussion

The current study determined that secondhand smoke exposure was positively associated with perinatal depression and suicidal ideation. Compared with women who had low secondhand smoke exposure, those exposed to secondhand smoke more frequently during the second and third trimesters exhibited a 4–7-fold higher risk of suicidal ideation, and women exposed to secondhand smoke more frequently and who were aged younger than 26–35 years had an increased risk of depressive symptoms.

We also found that secondhand smoke exposure was associated with depression, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies [59, 60]. The impact of secondhand smoke exposure on depressive symptoms especially affected women aged 26–35 years. No significance was observed for women aged 35 years or more. Previous studies have shown that younger antenatal and postnatal women have higher risks of experiencing depressive symptoms [61–63]; older women are believed to have the ability to adapt to changes in the external environment and to have fewer mood disorders [64]. The nonsignificant association between secondhand smoke exposure and depression for women aged <25 years in our study is probably due to the small sample size and its limited statistical power. More studies are required to clarify this relationship.

This is the first study to observe that women with secondhand smoke exposure more frequently had an increased risk of perinatal suicidal ideation, especially during the second and third trimesters. Two reasons could explain the difference among trimesters. First, approximately 87 % of pregnant women complain of nausea and vomiting during the first trimester [45]. Women may have an aversion to being exposed to secondhand smoke early in pregnancy because of physiological changes. Thus, they may attempt to limit their exposure to secondhand smoke. In addition, Peacock et al. in 1998 found a strong positive correlation between cotinine measures at 14 and 28 weeks [65]. Chiu [66] determined that urinary and serum cotinine levels were elevated as gestation progressed. It seems that pregnant women may experience different effects of secondhand smoke exposure throughout the 3 trimesters.

Certain mechanisms may explain the association between secondhand smoke exposure and depressed mood. Tobacco smoke affecting the neurotransmitter systems of pregnant passive smokers may reflect the role of neurotransmitter pathways in the biological mechanism of depression. Nicotine intensity may increase the plasma levels of CRH and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), resulting in the secretion of more cortisol, which consequently affects mood, cognition, and behavior by changing the availability of brain neurotransmitters [67]. Studies have further suggested that secondhand smoke exposure may reduce the levels of dopamine and GABA. These two biochemicals have been linked to depression [20, 34]. Additionally, passive smoking may also provoke a feeling of withdrawal, a symptom associated with depressed mood and major depressive episodes through the mechanism of augmented monoamine oxidase A binding in the brain [68].

Moreover, we found that pre-pregnancy smoking status was associated with suicidal ideation. In some prospective studies, smoking could explain suicidality risk more accurately than could other variables [69, 70]. Our study further identified that pre-pregnancy smoking status was a crucial risk factor for suicidal ideation among perinatal women. Previous studies have shown that smoking and suicidal behaviors are positively associated with sensation seeking [71, 72]. As both smoking and suicidal behaviors could be considered risk-taking behaviors, the link between suicidal ideation and smoking warrants more investigation in future studies.

Our results presented a null relationship between pre-pregnancy smoking and perinatal depression and anxiety. Although some studies have observed an association between smoking and depression [59, 73, 74], the link between smoking and anxiety was less clear [21]. Consistent with our null findings, a cross-sectional study in the Netherlands determined that anxiety and depressive symptoms were not associated with continued smoking for pregnant women [75]. Examining smoking intake might aid in clarifying the relationship between smoking and mood disorders; however, the number of active smokers during pregnancy in our study was too small for such analysis. In addition, smoking among women, especially during the perinatal period, is a sensitive topic. Women might feel hesitant to report their smoking behaviors, which could bias results toward the null. Smoking may jointly act with other physical and psychosocial factors to affect perinatal mood disorders. Future studies are suggested to recruit more active smokers during the perinatal period and to classify them by smoking intake for further examination.

There is a general awareness that tobacco exposure endanger maternal and fetal health. In our investigation, we found that pre-pregnancy smoking and secondhand smoke exposure increased risks to a woman's mental health during the perinatal period. Our investigation provides a compelling reason that we should advocate more restricted smoke-free legislation to prevent perinatal women from being exposed to secondhand smoke at home and in the workplace, especially during the second and third trimesters, to avoid adverse mental health outcomes. Appropriate intervention strategies to create smoke-free environments in the home and public places for perinatal women are essential. Huang et al. [76] used a transtheoretical model for preventive behavior against passive smoking by perinatal women. We suggest that this idea is expanded on by future studies and strategies.

This study had several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this was the first study to focus on the effects of secondhand smoke exposure on perinatal suicidal ideation. Second, this study used a larger sample than did previous studies on the effects of smoke and mental status during the perinatal period [32, 74, 75]. Third, the current study collected data from the entire perinatal period from the first trimester to 1 month post partum. Finally, we assessed the effects of pre-pregnancy smoking and secondhand smoke exposure on perinatal mental status simultaneously and adjusted for other risk factors that might have interfered with the mental status of the participating perinatal women.

The current study also had some limitations. First, this study used self-reported tobacco exposure and lacked biochemical assay data. This might have caused a bias because of differences in individual subjective recognition and recall. However, according to Chiu et al. [77], cotinine levels in the urine and blood of pregnant women were significantly correlated with their self-reported information provided using a questionnaire. Thus, the self-reported information in the current study can be considered to be fairly accurate. Nevertheless, because the Taiwan law prohibits maternal smoking during pregnancy and because of the stigma associated with female smoking in Taiwan, the accuracy of the assessment of smoking during or immediately before pregnancy should be considered carefully. Second, this study used a convenience sample from five cooperating hospitals, which might limit the generalizability of our results to all perinatal women in Taiwan. Third, some risk factors that may have influenced the perinatal mental condition were not included in our model, such as stressful events and physical illnesses. This may have biased our results. Finally, the wide 95 % CIs specifically for the effects of secondhand smoke exposure status on suicidal ideation were probably due to the small sample size of women with suicidal ideation and exposure of secondhand smoking during the perinatal period. Thus, the statistical power of these results might be limited.

Conclusion

Prenatal and postnatal women exposed to passive smoking are at risks of suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms, especially during the second and third trimesters and among younger women. This study extended knowledge of the effects of secondhand smoke exposure on perinatal mental health. In addition, our results support the importance of creating smoke-free environments for perinatal women. Further studies are suggested to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the association between secondhand smoke exposure and mental health among different trimesters and ages.

Abbreviations

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; OR, odds ratio; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

References

Simpson WJ. A preliminary report on cigarette smoking and the incidence of prematurity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1957;73(4):807–15.

Secker-Walker RH, Vacek PM, Flynn BS, Mead PB. Estimated gains in birth weight associated with reductions in smoking during pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1998;43(11):967–74.

DeLorenze GN, Kharrazi M, Kaufman FL, Eskenazi B, Bernert JT. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in pregnant women: the association between self-report and serum cotinine. Environ Res. 2002;90(1):21–32.

Kharrazi M, DeLorenze GN, Kaufman FL, Eskenazi B, Bernert Jr JT, Graham S, Pearl M, Pirkle J. Environmental tobacco smoke and pregnancy outcome. Epidemiology. 2004;15(6):660–70.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Munson ML. Births: final data for 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2003;52(10):1–113.

Ko TJ, Tsai LY, Chu LC, Yeh SJ, Leung C, Chen CY, Chou HC, Tsao PN, Chen PC, Hsieh WS. Parental smoking during pregnancy and its association with low birth weight, small for gestational age, and preterm birth offspring: a birth cohort study. Pediatr Neonatol. 2014;55(1):20–7.

Adult Smoking Behavior Surveillance System. 2015. Available from:http://tobacco.hpa.gov.tw/Show.aspx?MenuId=581.

Henderson CB. Ballistocardiograms after cigarette smoking in health and in coronary heart disease. Br Heart J. 1953;15(3):278–86.

Christian LM. Physiological reactivity to psychological stress in human pregnancy: current knowledge and future directions. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;99(2):106–16.

Lindsay JR, Nieman LK. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in pregnancy: challenges in disease detection and treatment. Endocr Rev. 2005;26(6):775–99.

Chrousos GP, Gold PW. The concepts of stress and stress system disorders. Overview of physical and behavioral homeostasis. JAMA. 1992;267(9):1244–52.

Holsboer F, Spengler D, Heuser I. The role of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the pathogenesis of Cushing’s disease, anorexia nervosa, alcoholism, affective disorders and dementia. Prog Brain Res. 1992;93:385–417.

Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS, Cottler LB, Stetner F, Tipp JE, Johnson J. Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression. JAMA. 1990;264(12):1546–9.

Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, Chilcoat HD, Andreski P. Major depression and stages of smoking. A longitudinal investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(2):161–6.

Pasco JA, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, Ng F, Henry MJ, Nicholson GC, Kotowicz MA, Berk M. Tobacco smoking as a risk factor for major depressive disorder: population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(4):322–6.

Li D, Yang X, Ge Z, Hao Y, Wang Q, Liu F, Gu D, Huang J. Cigarette smoking and risk of completed suicide: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(10):1257–66.

Beratis S, Lekka NP, Gabriel J. Smoking among suicide attempters. Compr Psychiatry. 1997;38(2):74–9.

Fishbain DA, Lewis JE, Gao J, Cole B, Steele Rosomoff R. Are chronic low back pain patients who smoke at greater risk for suicide ideation? Pain Med. 2009;10(2):340–6.

Nakata A, Takahashi M, Ikeda T, Hojou M, Nigam JA, Swanson NG. Active and passive smoking and depression among Japanese workers. Prev Med. 2008;46(5):451–6.

Bandiera FC, Arheart KL, Caban-Martinez AJ, Fleming LE, McCollister K, Dietz NA, Leblanc WG, Davila EP, Lewis JE, Serdar B, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure and depressive symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(1):68–72.

Taha F, Goodwin RD. Secondhand smoke exposure across the life course and the risk of adult-onset depression and anxiety disorder. J Affect Disord. 2014;168:367–72.

Morrell HER, Cohen LM. Cigarette smoking, anxiety, and depression. J Psychopathol Behav. 2006;28(4):283–97.

Quattrocki E, Baird A, Yurgelun-Todd D. Biological aspects of the link between smoking and depression. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2000;8(3):99–110.

Picciotto MR, Addy NA, Mineur YS, Brunzell DH. It is not “either/or”: activation and desensitization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors both contribute to behaviors related to nicotine addiction and mood. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;84(4):329–42.

Picciotto MR, Brunzell DH, Caldarone BJ. Effect of nicotine and nicotinic receptors on anxiety and depression. Neuroreport. 2002;13(9):1097–106.

Philip NS, Carpenter LL, Tyrka AR, Price LH. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and depression: a review of the preclinical and clinical literature. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2010;212(1):1–12.

Petty F. GABA and mood disorders: a brief review and hypothesis. J Affect Disord. 1995;34(4):275–81.

Xie C, Wen X, Niu Z, Ding P, Liu T, He Y, Lin J, Yuan S, Guo X, Jia D, et al. Comparison of secondhand smoke exposure measures during pregnancy in the development of a clinical prediction model for small-for-gestational-age among non-smoking Chinese pregnant women. Tob Control. 2014.

Chomba E, Tshefu A, Onyamboko M, Kaseba-Sata C, Moore J, McClure EM, Moss N, Goco N, Bloch M, Goldenberg RL. Tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure during pregnancy in two African countries: Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(4):531–9.

Hawsawi AM, Bryant LO, Goodfellow LT. Association Between Exposure to Secondhand Smoke During Pregnancy and Low Birthweight: A Narrative Review. Respir Care. 2015;60(1):135–40.

Lee BE, Hong YC, Park H, Ha M, Kim JH, Chang N, Roh YM, Kim BN, Kim Y, Oh SY, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure during pregnancy and infantile neurodevelopment. Environ Res. 2011;111(4):539–44.

Zhu SH, Valbo A. Depression and smoking during pregnancy. Addict Behav. 2002;27(4):649–58.

Goodwin RD, Keyes K, Simuro N. Mental disorders and nicotine dependence among pregnant women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(4):875–83.

Mbah AK, Salihu HM, Dagne G, Wilson RE, Bruder K. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and risk of antenatal depression: application of latent variable modeling. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(4):293–302.

Raisanen S, Lehto SM, Nielsen HS, Gissler M, Kramer MR, Heinonen S. Risk factors for and perinatal outcomes of major depression during pregnancy: a population-based analysis during 2002–2010 in Finland. BMJ Open. 2014;4(11):e004883.

Tavares D, Quevedo L, Jansen K, Souza L, Pinheiro R, Silva R. Prevalence of suicide risk and comorbidities in postpartum women in Pelotas. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2012;34(3):270–6.

O’Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8(1):37–54.

Horowitz JA, Murphy CA, Gregory KE, Wojcik J. A community-based screening initiative to identify mothers at risk for postpartum depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011;40(1):52–61.

Heron J, O’Connor TG, Evans J, Golding J, Glover V, Team AS. The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(1):65–73.

Reck C, Struben K, Backenstrass M, Stefenelli U, Reinig K, Fuchs T, Sohn C, Mundt C. Prevalence, onset and comorbidity of postpartum anxiety and depressive disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118(6):459–68.

Mauri M, Oppo A, Borri C, Banti S, group P-R. SUICIDALITY in the perinatal period: comparison of two self-report instruments. Results from PND-ReScU. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(1):39–47.

Gavin AR, Tabb KM, Melville JL, Guo Y, Katon W. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(3):239–46.

Lancaster CA, Gold KJ, Flynn HA, Yoo H, Marcus SM, Davis MM. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(1):5–14.

Poudevigne MS, O’Connor PJ. Physical activity and mood during pregnancy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(8):1374–80.

Nazik E, Eryilmaz G. Incidence of pregnancy-related discomforts and management approaches to relieve them among pregnant women. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(11–12):1736–50.

Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. Br Med J. 2001;323:257–60.

Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hennekens CH. A prospective study of passive smoking and coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1997;95(10):2374–9.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6.

Heh SS. Validation of the Chinese Version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: Detecting Postnatal Depression in Taiwanese Women. J Nurs Res. 2011;9(2):105–13.

Luke S, Salihu HM, Alio AP, Mbah AK, Jeffers D, Berry EL, Mishkit VR. Risk factors for major antenatal depression among low-income African American women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(11):1841–6.

Heh SS. Validation of the Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: detecting postnatal depression in Taiwanese women. Hu Li Yan Jiu. 2001;9(2):105–13.

Lee DT, Yip SK, Chiu HF, Leung TY, Chan KP, Chau IO, Leung HC, Chung TK. Detecting postnatal depression in Chinese women. Validation of the Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:433–7.

Spielberger CD. Notes and comments trait-state anxiety and motor behavior. J Mot Behav. 1971;3(3):265–79.

Chung SKL, Long CF. The study of amending the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Psychological Testing. 1984;31:27–36.

Zhang J, Gao Q. Validation of the trait anxiety scale for state-trait anxiety inventory in suicide victims and living controls of Chinese rural youths. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16(1):85–94.

Howard LM, Flach C, Mehay A, Sharp D, Tylee A. The prevalence of suicidal ideation identified by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in postpartum women in primary care: findings from the RESPOND trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:57.

Atlantis E, Goldney RD, Eckert KA, Taylor AW. Trends in health-related quality of life and health service use associated with body mass index and comorbid major depression in South Australia, 1998–2008. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(10):1695–704.

Xie RH, He G, Liu A, Bradwejn J, Walker M, Wen SW. Fetal gender and postpartum depression in a cohort of Chinese women. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(4):680–4.

Tan S, Courtney LP, El-Mohandes AA, Gantz MG, Blake SM, Thornberry J, El-Khorazaty MN, Perry D, Kiely M. Relationships between self-reported smoking, household environmental tobacco smoke exposure and depressive symptoms in a pregnant minority population. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15 Suppl 1:S65–74.

Salmasi G, Grady R, Jones J, McDonald SD, Knowledge Synthesis G. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(4):423–41.

Aras N, Oral E, Aydin N, Gulec M. Maternal age and number of children are risk factors for depressive disorders in non-perinatal women of reproductive age. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013;17(4):298–306.

Meltzer-Brody S, Boschloo L, Jones I, Sullivan PF, Penninx BW. The EPDS-Lifetime: assessment of lifetime prevalence and risk factors for perinatal depression in a large cohort of depressed women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(6):465–73.

Schatz DB, Hsiao MC, Liu CY. Antenatal depression in East Asia: a review of the literature. Psychiatry Investig. 2012;9(2):111–8.

Dakov T, Dimitrova V. Pregnancy and delivery in women above the age of 35. Akush Ginekol (Sofiia). 2014;53(1):13–20.

Peacock JL, Cook DG, Carey IM, Jarvis MJ, Bryant AE, Anderson HR, Bland JM. Maternal cotinine level during pregnancy and birthweight for gestational age. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27(4):647–56.

Chiu HT. Effects of Maternal Cigarette Smoking and Environmental Tobacco Smoke during Pregnancy on Birth Outcomes. Taiwan: China Medical University; 2005.

Stokes PE. The potential role of excessive cortisol induced by HPA hyperfunction in the pathogenesis of depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1995;5(Suppl):77–82.

Bacher I, Houle S, Xu X, Zawertailo L, Soliman A, Wilson AA, Selby P, George TP, Sacher J, Miler L, et al. Monoamine oxidase A binding in the prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices during acute withdrawal from heavy cigarette smoking. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(8):817–26.

Hemmingsson T, Kriebel D. Smoking at age 18–20 and suicide during 26 years of follow-up-how can the association be explained? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(6):1000–4.

McGee R, Williams S, Nada-Raja S. Is cigarette smoking associated with suicidal ideation among young people? Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):619–20.

Spillane NS, Muller CJ, Noonan C, Goins RT, Mitchell CM, Manson S. Sensation-seeking predicts initiation of daily smoking behavior among American Indian high school students. Addict Behav. 2012;37(12):1303–6.

Ortin A, Lake AM, Kleinman M, Gould MS. Sensation seeking as risk factor for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in adolescence. J Affect Disord. 2012;143(1–3):214–22.

Linares Scott TJ, Heil SH, Higgins ST, Badger GJ, Bernstein IM. Depressive symptoms predict smoking status among pregnant women. Addict Behav. 2009;34(8):705–8.

Ellis LC, Berg-Nielsen TS, Lydersen S, Wichstrom L. Smoking during pregnancy and psychiatric disorders in preschoolers. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(11):635–44.

Beijers C, Ormel J, Meijer JL, Verbeek T, Bockting CL, Burger H. Stressful events and continued smoking and continued alcohol consumption during mid-pregnancy. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86359.

Huang CM, Guo JL, Wu HL, Chien LY. Stage of adoption for preventive behaviour against passive smoking among pregnant women and women with young children in Taiwan. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(23–24):3331–8.

Chiu HT, Isaac Wu HD, Kuo HW. The relationship between self-reported tobacco exposure and cotinines in urine and blood for pregnant women. Sci Total Environ. 2008;406(1–2):331–6.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank each hospital, hospitals staff, and participant for assisting with data acquisition.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants NSC 102-2314-B-038-038-MY3 and NSC 99-2628-B-038-015-MY3 from the Ministry of Science and Technology and by Grant DOH101-HP-1206 from the Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan.

Availability of data and materials

A request to gain access to the data can be made by contacting the corresponding author. Access can be granted subject to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the research collaborative agreement guidelines. This is a requirement mandated for this research study by our ethnics committee and funders.

Authors’ contributions

YHC conducted and designed this study, and provided critical revision of the manuscript for crucial intellectual content. SCW assisted in data collection, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. JPH conducted the sample recruitment and provided technical suggestions. YLH and TSHL jointly managed all related activities including reviewing literature and designing and conducting the questionnaire. All authors were consulted in the writing of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from 3 Institutional Review Boards, namely the TMU-Joint Institutional Review Board, Mackay Memorial Hospital Institutional Review Board, and Taipei City Hospital Institutional Review Board, and was applicable for all 5 study hospitals. Signed informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from all respondents at the time of enrollment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety among perinatal women in Taiwan. (DOCX 20 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Weng, SC., Huang, JP., Huang, YL. et al. Effects of tobacco exposure on perinatal suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety. BMC Public Health 16, 623 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3254-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3254-z