Abstract

Background

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines have been widely introduced in immunization programs worldwide, however, it is not accepted in mainland China. We aimed to investigate the awareness and knowledge about HPV vaccines and explore the acceptability of vaccination among the Chinese population.

Methods

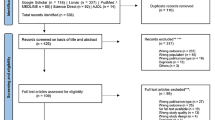

A meta-analysis was conducted across two English (PubMed, EMBASE) and three Chinese (China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wan Fang Database and VIP Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals) electronic databases in order to identify HPV vaccination studies conducted in mainland China. We conducted and reported the analysis in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Results

Fifty-eight unique studies representing 19 provinces and municipalities in mainland China were assessed. The pooled awareness and knowledge rates about HPV vaccination were 15.95 % (95 % CI: 12.87–19.29, I 2 = 98.9 %) and 17.55 % (95 % CI: 12.38–24.88, I 2 = 99.8 %), respectively. The female population (17.39 %; 95 % CI: 13.06–22.20, I 2 = 98.8 %) and mixed population (18.55 %; 95 % CI: 14.14–23.42, I 2 = 98.8 %) exhibited higher HPV vaccine awareness than the male population (1.82 %; 95 % CI: 0.50–11.20, I 2 = 98.5 %). Populations of mixed ethnicity had lower HPV vaccine awareness (9.61 %; 95 % CI: 5.95–14.03, I 2 = 99.0 %) than the Han population (20.17 %; 95 % CI: 16.42–24.20, I 2 = 98.3 %). Among different regions, the HPV vaccine awareness was higher in EDA (17.57 %; 95 % CI: 13.36–22.21, I 2 = 98.0 %) and CLDA (17.78 %; 95 % CI: 12.18–24.19, I 2 = 97.6 %) than in WUDA (1.80 %; 95 % CI: 0.02–6.33, I 2 = 98.9 %). Furthermore, 67.25 % (95 % CI: 58.75–75.21, I 2 = 99.8 %) of participants were willing to be vaccinated, while this number was lower for their daughters (60.32 %; 95 % CI: 51.25–69.04, I 2 = 99.2 %). The general adult population (64.72 %; 95 % CI: 55.57–73.36, I 2 = 99.2 %) was more willing to vaccinate their daughters than the parent population (33.78 %; 95 % CI: 26.26–41.74, I 2 = 88.3 %). Safety (50.46 %; 95 % CI: 40.00–60.89, I 2 = 96.6 %) was the main concern about vaccination among the adult population whereas the safety and efficacy (68.19 %; 95 % CI: 53.13–81.52, I 2 = 98.6 %) were the main concerns for unwillingness to vaccinate their daughters.

Conclusions

Low HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge was observed among the Chinese population. HPV vaccine awareness differed across sexes, ethnicities, and regions. Given the limited quality and number of studies included, further research with improved study designis necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cervical cancer, one of the most common cancers observed in females [1], affects more than 529,000 annually around the world [2]. More than 85 % of the global cervical cancer burden occurs in developing countries [2], with 75,500 incidences reported annually in China. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the most important risk factor for cervical cancer [3]. Although a single HPV infection can easily be eliminated through the immune system, malignant transformation of cervical epithelial cells may be induced in a small proportion of women affected by persistent virus infection.

Vaccines have always been among the most effective interventions for infectious diseases [4]. Prophylactic vaccines of cervical cancer manufactured by Merck &Co. have been approved by FDA and have been commercially available since 2006 [5]. The approval of vaccines for the HPV increased the possibility of eradicating cervical cancer in the near future. However, it is noteworthy that awareness of HPV and the general attitude towards vaccination were crucial factors for acceptance of vaccination among the population. In addition, increasing number of studies addressing the hesitation to get vaccinated have been conducted in the recent years, portraying the challenging and dynamic period of indecisiveness concerning HPV vaccination [6].

The HPV vaccine has been widely introduced in the vaccination programs of Hong Kong, however, is not popularly accepted in Mainland China at present. In addition, despite the numerous published studies focusing on the topic of HPV and vaccination in recent years, there is no comprehensive information concerning the acceptance and obstacles associated with vaccination among the population of Mainland China. In order to develop a practical vaccination program in the future, it is imperative to assess the level of awareness and knowledge about HPV, and the general attitude towards HPV vaccination among the Chinese population, as they are important behavioral determinants that will ultimately affect the acceptance of vaccination among the Chinese population. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis in order to gain a better understanding of this issue that may help generate new ideas to make future generalization of HPV vaccination possible in China.

Methods

Search strategy

The meta-analysis was conducted in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [7]. The Chinese literature was searched using the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wan Fang Database and VIP Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals (VIP) using the keywords “HPV vaccine OR cervical vaccine”. The literature in English was searched using PubMed and EMBASE, and relevant studies were identified with the search terms “HPV OR cervical cancer” AND “vaccine OR vaccination OR immunization” AND “awareness OR knowledge OR acceptability OR acceptance OR willingness OR perception OR attitude OR recognition” AND “China OR Chinese.” The publication time was limited to 2006–2015, as HPV vaccine was introduced in the world in 2006. Data retrieval was supplemented by manually searching for the reference list of key reviews and references from retrieved studies. No language restriction was imposed.

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria for the epidemiological studies were the following: (1)study involved at least one of the key terms “HPV vaccine awareness”, “knowledge”, and “acceptability”for any region of Mainland China (excluding studies conducted in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macao due to differencesin socio-economic levels and health policies between these regions and Mainland China), (2) original data was available regardless of whether it was obtained directly from the article or traced from secondary data in the article. Studies that examining the effects of health educational interventions were excluded.

Data extraction

A data abstraction form was constructed after scanning the selected articles. For each included study, we extracted the following information: author, publication year, region, study instrument, study subject (age, sex and ethnicity), sampling method, sample size (N), the number of participants for the assessment of HPV vaccine awareness, knowledge, and acceptance, or the rate percentage proportions for these studied factors. We also extracted the reasons for unwillingness to be vaccinated if this information was available. The number of studied cases(n) and sample size(N) were the two necessary parameters for the calculation of the pooled rates of HPV vaccine awareness, knowledge, and acceptance of vaccination in the meta-analysis. In particular, the number of studied cases (n) was obtained directly from the original studies or by multiplying the sample sizes (N) with the proportions (%) associated with the investigated factors reported in the original studies.

Quality assessment

We employed a flexible appraisal scale suggested by Iain Crombie [8] for the assessment of the quality of cross-sectional studies. The scale contains seven indexes: (1) design is scientific, (2) data collection strategy is reasonable, (3) sample response rate is reported, (4) samples can represent the general population well, (5) the research purpose and method is reasonable, (6) the test efficiency is reported, (7) the statistical method is reasonable. For each index, the study was scored “1,” “0,”or “0.5” for “yes,” “no,”or “unclear,” respectively. The maximum score in the scale is 7 points, with scores of 6.0–7.0 points as grade A, scores of 4.0–5.5 points as grade B, and scores of less than 4.0 points as grade C.

Data analysis

We used “rate” to evaluate the studied items. The rate for HPV vaccine awareness was calculated by dividing the number of cases who were aware of HPV vaccine (n1) by the sample size (N); the rate for HPV vaccine knowledge was calculated by dividing the number of cases who knew the relationship between HPV (vaccine) and cervical cancer (n2) by the sample size (N); the rate for acceptance to be vaccinated was calculated by dividing the number of cases who were willing to get vaccinated (n3) by the sample size (N); the rate for acceptance of parents to vaccinate their daughters was calculated by dividing the number of cases who were willing to vaccinate their daughters (n4) by the sample size(N); the rate for reasons of unwillingness to be vaccinated was calculated by dividing the number of cases who gave a reason (n5) by the number of cases who were unwilling to be vaccinated (N-n3).

Meta-analysis was conducted using a random effects model. Given the requirement for normalization of single rate in meta-analysis, an arcsine transformation for the original rate was performed to meet the requirement [9]. Statistical heterogeneity among the studies was estimated by Chi-square test at the significance level of P < 0.10, and using the I-square (I 2) statistic to quantify the heterogeneity of the results. Publication bias was detected by Egger’s test (P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant) [10]. R statistical software (Version 2.11.1) was used for all the calculations.

Consent statement

As this study was a meta-analysis, we did not include any humans and animals. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Results

Screening process

Our search returned 1683 articles. A flow diagram of the selection process is shown in Fig. 1. Of the original articles, 1561 articles that were not clearly relevant to the analysis were excluded. After diligently reading the full text of the remaining 122 studies, 64 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Consequently, 58 observational studies [11–68] were included for the meta-analysis.

Study characteristics

We included 58 individual studies [11–68] representing 19 provinces and municipalities in Mainland China (Table 1). Eighty-three thousand, seven hundred and five participants were interviewed, the majority of which were females. Nearly all the studies were published after 2009, and 38 studies were published in the recent three years. A questionnaire survey was conducted for all the studies included in the analysis, 12 of which were interview-administered, while nine were self-administered questionnaires (Table 1). After conducting a quality assessment on the included studies, 51 studies were categorized as grade A, and seven as grade B (Table 2).

Awareness and knowledge of HPV vaccine

Awareness and knowledge of HPV vaccination among different populations were reported in 43 and 21 studies, respectively. The pooled awareness rate and knowledge rate concerning HPV vaccination was 15.95 % (95 % CI: 12.87–19.29, I 2 = 98.9 %), and 17.55 % (95 % CI: 12.38–24.88, I 2 = 99.8 %), respectively (Table 3). Figures 2 and 3 show forest plots of meta-analysis for HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge in mainland China.

Acceptability of HPV vaccination

We explored the acceptability of HPV vaccination for individuals and their daughters. Thirty-five studies addressed participants’ willingness to be vaccinated, while 12 studies addressed the willingness of parents to get their daughters vaccinated. We found that the willingness of participants to be vaccinated was 67.25 % (95 % CI: 58.75–75.21, I 2 = 99.8 %) while their willingness to get their daughters vaccinated was 60.32 % (95 % CI: 51.25–69.04, I 2 = 99.2 %) (Table 3). Figures 4 and 5 show forest plots of meta-analysis for acceptability of HPV vaccination (for themselves and their daughters) in mainland China.

Reasons for unwillingness to be HPV vaccinated

Reasons for the unwillingness of individuals to be HPV vaccinated varied across studies. Nineteen studies explored reasons for participants’ reluctance to HPV vaccination. Among participants who were unwilling to be vaccinated, 33.63 % (95 % CI: 27.50–40.05, I 2 = 97.2 %) respondents believed that they had a low risk of developing HPV infection, genital warts, or even cervical cancer. Other respondents were worried about the limited use of HPV vaccine in China (36.31 %; 95 % CI: 29.67–43.22, I 2 = 97.7 %). Respondents who were concerned with the safety and the efficacy of HPV vaccination accounted for 50.46 % (95 % CI: 40.00–60.89, I 2 = 96.6 %) and 30.18 % (95 % CI: 23.96–36.79, I 2 = 97.3 %), respectively. Participants who questioned the source of the vaccine and communicated a concern regarding the high price of the vaccine were 32.17 % (95 % CI: 21.14–43.30, I 2 = 99.2 %) and 23.72 % (95 % CI: 13.64–35.59, I 2 = 98.2 %), respectively (Table 3).

Reasons for unwillingness of parents to vaccinate their daughters

Seven studies explored the reasons for participants’ reluctance to get their daughters HPV vaccinated. Among them, 32.61 % (95 % CI: 22.03–44.18, I 2 = 94.5 %) respondents were concerned regarding the limited use of HPV vaccine in China to date. Some respondents (68.19 %; 95 % CI: 53.13–81.52, I 2 = 98.6 %) doubted the safety and efficacy of the HPV vaccine. Only 17.24 % (95 % CI: 13.87–20.90, I 2 = 82.8 %) of the respondents doubted the vaccine source. In addition, 28.37 % (95 % CI: 13.69–45.90, I 2 = 99 %) of the respondents considered their children to be too young for vaccination (Table 3).

Subgroup analysis and meta-regression

A subgroup analysis indicated that the awareness of HPV vaccine differed across sexes (P = 0.033), ethnicities (P = 0.017), and regions (P = 0.031). We observed a higher HPV vaccine awareness among the female population (17.39 %; 95 % CI: 13.06–22.20, I 2 = 98.8 %) and mixed population (18.55 %; 95 % CI:14.14–23.42, I 2 = 98.8 %) relative to the male population (1.82 %; 95 % CI: 0.50–11.20, I 2 = 98.5 %). We also found that populations of mixed ethnicity have lower HPV vaccine awareness (9.61 %; 95 % CI: 5.95–14.03, I 2 = 99.0 %) compared to population of Han (20.17 %; 95 % CI: 16.42–24.20, I 2 = 98.3 %). Among different regions, the HPV vaccine awareness was higher in EDA (17.57 %; 95 % CI: 13.36–22.21, I 2 = 98.0 %) and CLDA (17.78 %; 95 % CI: 12.18–24.19, I 2 = 97.6 %) compared to WUDA (1.80 %; 95 % CI: 0.02–6.33, I 2 = 98.9 %). Subgroup analysis revealed that acceptability to be vaccinated varied among studies conducted using different sampling methods (P = 0.022). The acceptability of vaccination among cluster-sampled population (72.45 %; 95 % CI: 52.22–88.76, I 2 = 99.9 %) was higher compared to the convenience-sampled population (53.53 %; 95 % CI: 41.95–64.92, I 2 = 99.5 %). The subgroup analysis showed that acceptability for parents to vaccinate their daughters differed across ages (P = 0.014) and sampling methods (P = 0.038). General adult population (64.72 %; 95 % CI: 55.57–73.36, I 2 = 99.2 %) was more willing to vaccinate their daughters than parent population (33.78 %; 95 % CI: 26.26–41.74, I 2 = 88.3 %). Randomized sampling method showed a higher acceptability for vaccination of daughters (72.75 %; 95 % CI: 67.66–77.56, I 2 = 92.9 %) compared to cluster sampling method (48.54 %; 32.37–64.88, I 2 = 99.4 %) (Table 4). Meta-regression analysis was also performed but failed to explain the source of heterogeneity.

Publication bias

Egger’s test was performed to assess the publication bias. The results did not show evidence of publication bias (all P > 0.05) (Table 3).

Discussion

This is the first meta-analysis study conducted for the assessment of HPV vaccine related awareness, knowledge and acceptability among the Chinese population. Our meta-analysis identified low awareness (15.95 %) and low knowledge (17.55 %) of HPV vaccine among the Chinese population. The rates were lower compared to many other countries. Studies conducted in Turkey showed that HPV vaccine awareness among undergraduate students in Turkey was 44.5 % [69], while 27.9 % of respondents knew that HPV vaccines can prevent cervical cancer [70]. In addition, the HPV vaccine awareness rates were found to be in the 67.1–71.3 % range in the USA, UK and Australia [71]. The higher awareness rate of HPV vaccine and related knowledge in these countries may be due to the intervention programs and increased media coverage [72–74]. The low level of HPV vaccine awareness may greatly influence its promotion in China. In subgroup analysis, the pooled rate of HPV vaccine awareness was higher among females (17.39 %) and mixed population (18.55 %) compared to the male population (1.82 %). In the Chinese tradition, males play an important role in decision-making in the family, the low awareness of HPV vaccine may influence the acceptability of vaccination for their daughters [53]. We also found that populations of mixed ethnicity have lower HPV vaccine awareness rates (9.61 %) compared to population of Han (20.17 %). In addition, a study in England showed that HPV vaccine awareness was lower among ethnic minority groups (6–18 %) compared to white women (39 %), and that ethnic minorities have lower uptake of vaccination [75, 76]. These findings suggest that potential ethnic inequalities and cultural barriers should be identified for the prevention of cervical cancer [76]. Among different regions, HPV vaccine awareness was higher in EDA (17.57 %) and CLDA (17.78 %) compared to WUDA (1.80 %). In fact, eastern and central areas benefit from abundant healthcare resources and strong economies compared to western or some undeveloped regions. The difference between different geographical areas in China revealed that socio-economic status is a factor that influences the HPV vaccine awareness.

In addition, we found a relative high acceptability of HPV vaccination (67.25 % for themselves and 60.32 % for daughters). However, this rate declines in the high-end of the level across the world (59 % to 100 %) [77–79]. In subgroup analysis, the acceptability to be vaccinated among cluster-sampled population (72.45 %) was higher than convenience-sampled population (53.53 %), and randomized sampling method (72.75 %) showed a higher acceptability for vaccination of daughters compared to cluster sampling method (48.54 %). This is an indication that acceptability of vaccination among the population may be higher if rigorous sampling methods, such as randomized sampling method, are used. Subgroup analysis showed that parental acceptability of vaccination (33.78 %) was lower compared to the general adult population (64.72 %). Moreover, the acceptability rate (33.78 %) was lower compared to similar studies conducted in other countries. A similar study in Sweden reported that 76 % of participated parents were willing to vaccinate their daughters [80]. In addition, studies in Africa showed that parents with good knowledge of HPV vaccine were more willing to vaccinate their children than those with poor knowledge [81]. Population’s attitude and acceptance toward HPV vaccination is an important determinant for the success of HPV vaccine promotion in China in the future, which necessitates, the identification of the main obstacles concerning the acceptability of vaccination among the Chinese population.

The primary obstacles concerning vaccination acceptability for responders were the safety and efficacy of the HPV vaccine. HPV vaccines have been proved safe and efficient against HPV infection [82, 83]. WHO recommended HPV vaccination for both young women and men before the onset of sexual activity [84]. In recent years, many studies have investigated HPV vaccine safety and adverse events. Both of the HPV vaccines are related to high rates of injection site reactions, such as pain, swelling and redness which maybe due to a possible VLP-related (VLP, Virus-like particles) inflammation process [85]. However, these outcomes are usually for a short duration and recovery is quick [86]. Most reported adverse events were mild or moderate in intensity [87–98], and serious vaccination-related adverse events, such as anaphylaxis, are rare [86]. Similarly, other studies reported that there were no vaccine related deaths in the included studies [99]. Furthermore, a review concluded that the prophylactic vaccines against HPV appear safe based on the assessment of reported adverse events by governmental databases and independent researchers [100].

Sufficient scientific evidence has clarified many of the misunderstandings related to vaccine safety, however, the concerns related to vaccination are still increasing [101]. Public confidence in vaccines is particularly important. If vaccination is not trusted, the hesitance to be vaccinated may lead to delay and refusal, resulting in the disintegration of related research and delivery programs, and may even result in disease outbreak [102, 103]. The segmented information from media may amplify vaccine related concerns, resulting in the circulation of anxiety among the public [104]. It is the responsibility of the healthcare providers to rectify the misconceptions related to vaccination among the population, while acknowledging parents' concerns, updating their knowledge on vaccine related health information by paying close attention to the latest scientific research, and allocating sufficient time to instruct the concerned population on vaccine safety [101].

Mainland China has not introduced HPV vaccination into the routine immune vaccination program, experiences from other countries that implemented HPV vaccination program can be taken as an example. In many counties, an organized vaccination program is recommended to increase the vaccination coverage. It is now widely believed that the most urgent public-health issue is to increase HPV vaccination coverage and improve completion of the vaccination schedule, especially among sexually active females [105]. Thus, many studies further explored means to boost vaccination rates. An analysis showed that HPV vaccination rate could not be increased solely by educational intervention. A research conducted in America showed that a provider-centered PICME (Performance Improvement Continuing Medical Education) intervention, which includes repeated communication, focused education, and individualized feedback, proved an effective measure for sustained improvement of vaccination rates [106]. Another study showed obvious differences between adopters and non-adopters via in-depth interviews, emphasizing that vaccinated women benefit from supportive social influences whereas unvaccinated women’s concerns regarding the safety and efficacy of short- and long-term vaccination was influenced by their interpersonal network [107].

Further research to perfect the existing HPV vaccines is needed. Moreover, as a measure of primary prevention, HPV vaccination should be performed alongside cervical screening (secondary prevention) as a clear strategy for the prevention of cervical cancer.

The strength of our analysis is that the evaluation of the recently published papers about HPV vaccination among the Chinese population allowed us to offer evidence-based advice for the implementation of HPV vaccination in Mainland China in future. However, there were some limitations in this study. Obvious heterogeneity existed in the meta-analysis. We tried to perform meta-regression analysis to explain the source of heterogeneity, however, significant heterogeneity remained unexplained after an exploration of the relative factors, such as sampling method and population characteristics. In fact, for observational studies that involve proportions, substantial heterogeneity is a common dilemma [108]. Although a theoretical framework was designed, it is difficult to ensure that all the original studies used rigorous testing and validation for the investigation as previously outlined in real circumstances. These variations and constraints may account, at least partly, towards the observed heterogeneity. In addition, measures of studied factors were inconsistent among studies, and it is difficult to clarify the inconsistencies due to the difference of measurements across included studies or true variability among the population [109].

Conclusions

In conclusion, this meta-analysis proved low HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge among the Chinese population. HPV vaccine awareness differed across sexes, ethnicities, and regions. However, given the limited quality and number of included studies, future studies with improved design are necessary for the verification of our findings.

Abbreviations

- HPV:

-

Human Papillomavirus

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- EDA:

-

Eastern developed areas

- CLDA:

-

Central less developed areas

- WUDA:

-

Western or undeveloped areas

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- I2 :

-

I-square

- VLP:

-

Virus-like particles

- PICME:

-

Performance Improvement Continuing Medical Education

References

Herzog TJ. New approaches for the management of cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90(3 Pt 2):S22–7.

Mishra GA, Pimple SA, Shastri SS. An overview of prevention and early detection of cervical cancers. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2011;32(3):125–32.

Arbyn M, Walker A, Meijer CJ. HPV-based cervical-cancer screening in China. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(12):1112–3.

Levine OS, Bloom DE, Cherian T, de Quadros C, Sow S, Wecker J, Duclos P, Greenwood B. The future of immunisation policy, implementation, and financing. Lancet. 2011;378(9789):439–48.

Choi HC, Leung GM, Woo PP, Jit M, Wu JT. Acceptability and uptake of female adolescent HPV vaccination in Hong Kong: a survey of mothers and adolescents. Vaccine. 2013;32(1):78–84.

Jarrett C, Wilson R, O’Leary M, Eckersberger E, Larson HJ, Hesitancy SWGoV. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy - A systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4180–90.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Combie I. Pocket guide to critical appraisal. London: John Wiley&Sons; 1996.

Meiling L, Hongzhuan T, Quan Z, Shaya W, Chang C, Yawei G, Lin S. Realizing the meta-analysis of single rate in R software. J Evid Based Med. 2013;13(3):181–8.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Jing X, Yanqin L. Analysis of HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and attitude among College students. Youjiang National Med J. 2014;36(1):72–3.

Xiaojing M, Xiangju M, Jieyun D, Liuge Z, Jing Z, Qianqian Z, Ningning S. Analysis of human papiollomavirus recognition and its influential factors among adult female. Prog Obstet Gynecol. 2013;22(6):491–3.

Bo C. The analysis of the awareness of human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccine and the willingness of vaccination among Urban and Rural women. Dalian Medical University: Master; 2010.

Juan L. The Analysis of the awareness of human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccine among Doctors and government officials. Dalian Medical University: Master; 2011.

Xuemin W, Xiangxian F, Yanli Z, Cailing W, Youlin Q. Cervical cancer screening and acceptance of HPV vaccine in women of Shanxi province. Chin J Pubilic Health. 2012;28(5):650–1.

Hong Y, Zhang C, Li X, Lin D, Liu Y. HPV and cervical cancer related knowledge, awareness and testing behaviors in a community sample of female sex workers in China. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:696.

Shujuan S, Tianfu Y, Liqin Z. HPV infection in female and the cognition about HPV and HPV vaccine. J Tianjin Med Univ. 2013;19(2):127–30.

Wenyu X, Juanwen C, Xiaoyan L, Jiaoying Y. Human papilloma virus infection rate of young female and the survey analysis related of knowledge, attitude and behavior. J Qiqihar Univ Med. 2013;34(13):1880–2.

Chenglian Y, Gang C, Xiumei H, Yueqiu C, Caipin H, Sujuan N, Tie L. Human papillomavirus infection status and investigation of HPV recognition of migrant women. Zhejiang Prev Med. 2012;24(12):64–6.

Wang SM, Zhang SK, Pan XF, Ren ZF, Yang CX, Wang ZZ, Gao XH, Li M, Zheng QQ, Ma W et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine awareness, acceptability, and decision-making factors among Chinese college students. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(7):3239–45.

Xiange Long,Chuyue C,Li Z,Yeping C. Investigation of human papillomavirus related knowledge recognition level among higher vocational medical laboratory students. Sci Technol Inf. 2011;32:244-244.

Lina X, Qianya Z, Tao L, Lirong J, Liqin Z, Xiangxian F, Junfei M, Fanghui Z. Investigation of human papillomavirus vaccine recognition and vaccination willingness in HUABEI region. Shanxi Med J. 2013;18:990–3.

Baojian F. Investigation of the cervical cancer screening, HPV infection and HPV vaccine cognitive level among the women at clinical of gynecology. Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine: Master; 2009.

Jing C, Rezim D, Abliz G, Mijit P, Hua L. Investigation of the awareness of cervical cancer and HPV in Uyghur men from rural area of Kashgar Payzawat of Xinjiang. J Xinjiang Med Univ. 2013;36(9):1365–8.

Ying W. An investigation of the cognition and reception towards HPV vaccine among women living in Hangzhou. Chin Prev Med. 2011;12(4):321–3.

Ablimit X, Abduxkur G, Abliz G. The investigation of the factors related to the knowledge of cervical cancer and HPV in Uygur women. J Xinjiang Med Univ. 2009;32(5):522–5.

Li L. The Investigation of the Prevenlance of the HPV infection, Cervical Cancer and the Acceptance of HPV Vaccine in Uygur Women in Xinjiang Province. Xinjiang Medical University: Doctor; 2010.

Haishan H, Xueling W, Zefang R, Xiaomin Z, Fanghui Z, Youlin Q. Investigation on acceptance of HPV vaccination and its determinants among the parents of junior high school students in Guangzhou. Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2014;18(7):659–62.

Xin H, Shucai L, Mingchen C, Xiaoli W, Hongtu L, Tianjiang M. Investigation on consciousness about human papillomavirus and cervical cancer in college students. Mod Prev Med. 2010;37(21):4097–8.

Dong M, Hui Q, Haiqiu W, Tianming L, Yan Y, Ou L. Investigation on the cognition and acceptability of medical personnel to human papillomavirus and its vaccine in a hospital of Tangshan city. Matern Child Health Care China. 2012;27(3):397–400.

Haiqiu W, Dong M, Disi B. Investigation on the cognitions and attitudes of gynecologists and obstetricians to HPV and its vaccines in Tangshan city. Matern Child Health Care China. 2011;26(36):5772–4.

Abduxkur G, Ismayil A, Abliz G. Investigation on the cognitive degree of Uighur men to cervical cancer and HPV in Hetian prefectureof Xinjiang Uighur autonomous region. Matern Child Health Care China. 2012;27:1203–5.

He H, Fanghui Z, Yao X, Shaoming W, Xiongfei P, Hui L, Feng C, Chunxia Y, Youlin Q. Knowledge and attitude toward HPV and prophylactic HPV vaccine among college students in Chengdu. Mod Prev Med. 2013;40(16):3071–3.

Li J, Li LK, Ma JF, Wei LH, Niyazi M, Li CQ, Xu AD, Wang JB, Liang H, Belinson J et al. Knowledge and attitudes about human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccines among women living in metropolitan and rural regions of China. Vaccine. 2009;27(8):1210–5.

Wen Y, Pan XF, Zhao ZM, Chen F, Fu CJ, Li SQ, Zhao Y, Chang H, Xue QP, Yang CX. Knowledge of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, cervical cancer, and HPV vaccine and its correlates among medical students in Southwest China: a multi-center cross-sectional survey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(14):5773–9.

Zhao FH, Tiggelaar SM, Hu SY, Zhao N, Hong Y, Niyazi M, Gao XH, Ju LR, Zhang LQ, Feng XX et al. A multi-center survey of HPV knowledge and attitudes toward HPV vaccination among women, government officials, and medical personnel in China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(5):2369–78.

Hui Z, Dongxue Y, Chaoxin L, Shaoming W, Yang X, Yuehua P, Dongming W, Jincong Y, Weiquan W. Parental acceptance of junior high school students for human papillomavirus vaccination: a survey at one school in Wuhan. J Public Health Prev Med. 2014;25(1):49–52.

Zhang SK, Pan XF, Wang SM, Yang CX, Gao XH, Wang ZZ, Li M, Ren ZF, Zhao FH, Qiao YL. Perceptions and acceptability of HPV vaccination among parents of young adolescents: a multicenter national survey in China. Vaccine. 2013;31(32):3244–9.

Yanhua H, Gaoping Z, Yan X, Yanhua J, Deyan L, Xinyin Z. A research about awareness and acceptance of HPV vaccines degrees in Shenzhen Luohu community. Mod Hosp. 2014;14(5):144–6.

Dong M, Yan W, Ou L, Wenchang W. Study on medical students knowledge and attitudes regarding HPV and its vaccine. Matern Child Health Care China. 2013;28(28):4699–702.

Mei H, Fanghui Z, Ying H, Jihong D, Longyu L. Survey on awareness and attitude towards HPV and HPV vaccination for cervical cancer prevention among urban women and medical professionals. China Cancer. 2011;20(7):483–8.

Lixia Z. Survey of knowledge and infectious status of human papilloma virus in community and maternal female outpatients. China Trop Med. 2011;11(4):456–7.

Jun Y, Xiaoli W, Xiaohui W. Survey on cognition of HPV vaccine among women living in high prevalence area of cervical cancer in Gansu Province. Chin J Health Educ. 2013;29(10):913–6.

Jing Y, Hongying Y, Zhiling Y, Xianjie T. The survey on female sexuality and HPV awareness in Linxiang district of Yunnan province. Chongqing Yixue. 2013;29:3532–3.

Wei X, Meilu B. Women’s knowledge, attitude, and international concerning cervical cancer screening and human papillomavirus vaccine. J China Japan Friendship Hosp. 2009;23(2):79–82.

Suwen F. Women’s knowledge of Human papillomavirus(HPV) and their attitude towards HPV vaccine. Zhejiang University: Master; 2010.

Yanqiu Z, Kai Z, Zhihong L, Zhangwei, Ruifang W. Analysis of cognition of women and medical personnel on HPV vaccine in Shenzhen city. Mod Diagn Treat. 2015;26(16):3683–4.

Wenliu X, Bixia Z, Peipei J. Analysis of cognition and attitude of inpatients on HPV vaccine related knowledge in three grade A hospital in Hengyang city. Chin Nurs Res. 2015;29(4):1373–5.

Ling W, Yanqiong O, Xiaohui W. Analysis of knowledge of cervical and HPV vaccine among 125 student nurses. J Nurs. 2015;22(17):47–50.

Ling C, Can G, Shumei L. Study on full-time female medical masters’sexual behaviors and knowledge regarding human papillomavirus infection. Med Recapitulate. 2015;21(13):2481–3.

Lihong C. Survey of infection rate and knowledge of HPV vaccine among women in Dongguan city, Guancheng district. Shenzhen J Integr Tradit Chin West Med. 2015;25(19):188–90.

Zou H, Wang W, Ma Y, Wang Y, Zhao F, Wang S, Zhang S, Ma W. How university students view human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination: A cross-sectional study in Jinan, China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(1):39-46.

Zou H, Meng X, Jia T, Zhu C, Chen X, Li X, Xu J, Ma W, Zhang X. Awareness and acceptance of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among males attending a major sexual health clinic in Wuxi, China: A cross-sectional study. Hum Vaccin immunother. 2015 (Epub ahead of print).

Zhang SK, Pan XF, Wang SM, Yang CX, Gao XH, Wang ZZ, Li M, Ren ZF, Zheng QQ, Ma W et al. Knowledge of human papillomavirus vaccination and related factors among parents of young adolescents: a nationwide survey in China. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(4):231–5.

Xiaomin Z, Zefang R, Xueling W, Wei L, Youlin Q. Knowledge and attitude of the students in Sun Yat-sen University regarding human papillomavirus and its vaccine. Mod Prev Med. 2015;42(10):1822–5.

Wang W, Ma Y, Wang X, Zou H, Zhao F, Wang S, Zhang S, Zhao Y, Marley G, Ma W. Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccine among parents of junior middle school students in Jinan. China Vaccine. 2015;33(22):2570–6.

Qiong L, Dongling Q, Wenliu X, Yanping W. Survey of knowledge of HPV infection among 590 vocational school students. Today Nurs. 2015;5:158–9.

Qiaoyang Z, Chuncha W, Yaping X, Yanyue C. Cervical cancer incidence and knowledge of cervical cancer and HPV among women. Chin J Pub Health Manage. 2015;31(5):768–9.

Qian S, Hong L, HUa L, Liping Y. Survey of infection situation and knowledge of high risk HPV among women working in entertainment places in Gaoqiao area International. J Lab Med. 2015;36(8):1018–25.

Liping M, Jianmei L, Yanhong J, Yuanwen L, Xuan H, Li Y. Analysis of women’s cognition to HPV and HPV vaccine in Bao’ann District. Shenzhen City J Pub Health Prev Med. 2015;26(5):54–7.

Juhong L, Kai Z. Survey of HPV vaccine knowledgement and demand situation. Chin Gen Pract Nurs. 2015;13(16):1562–3.

Gu C, Niccolai LM, Yang S, Wang X, Tao L. Human papillomavirus vaccine acceptability among female undergraduate students in China: the role of knowledge and psychosocial factors. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(19–20):2765–78.

Bixia Z, Wenliu X, Peipei J, Wangrong, Yanping W. Survey of HPV and HPV vaccine among women in Hengyang city. Chin Nurs Res. 2015;29(2):755–7.

Ayizuoremu · mutailipu, Sayipujiamali · mijiti, Lin GG. Investigation and analysis on cognition of cervical cancer,HPV and HPV vaccine among Uygur and Han women in Xinjiang. Mater Child Health Care China. 2015;30(3):434–7.

Abudukadeer A, Azam S, Mutailipu AZ, Qun L, Guilin G, Mijiti S. Knowledge and attitude of Uyghur women in Xinjiang province of China related to the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:110.

Pan XF, Zhao ZM, Sun J, Chen F, Wen QL, Liu K, Song GQ, Zhang JJ, Wen Y, Fu CJ et al. Acceptability and correlates of primary and secondary prevention of cervical cancer among medical students in southwest China: implications for cancer education. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110353.

Fu CJ, Pan XF, Zhao ZM, Saheb-Kashaf M, Chen F, Wen Y, Yang CX, Zhong XN. Knowledge, perceptions and acceptability of HPV vaccination among medical students in Chongqing, China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(15):6187–93.

Hu SY, Hong Y, Zhao FH, Lewkowitz AK, Chen F, Zhang WH, Pan QJ, Zhang X, Fei C, Li H et al. Prevalence of HPV infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and attitudes towards HPV vaccination among Chinese women Aged 18–25 in Jiangsu Province. Chin J Cancer Res. 2011;23(1):25–32.

Rathfisch G, Gungor I, Uzun E, Keskin O, Tencere Z. Human papillomavirus vaccines and cervical cancer: awareness, knowledge, and risk perception among Turkish undergraduate students. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(1):116–23.

Ozyer S, Uzunlar O, Ozler S, Kaymak O, Baser E, Gungor T, Mollamahmutoglu L. Awareness of Turkish female adolescents and young women about HPV and their attitudes towards HPV vaccination. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(8):4877–81.

Marlow LA, Zimet GD, McCaffery KJ, Ostini R, Waller J. Knowledge of human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccination: an international comparison. Vaccine. 2013;31(5):763–9.

Pitts MK, Dyson SJ, Rosenthal DA, Garland SM. Knowledge and awareness of human papillomavirus (HPV): attitudes towards HPV vaccination among a representative sample of women in Victoria, Australia. Sex Health. 2007;4(3):177–80.

Reiter PL, Stubbs B, Panozzo CA, Whitesell D, Brewer NT. HPV and HPV vaccine education intervention: effects on parents, healthcare staff, and school staff. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(11):2354–61.

Hopfer S. Effects of a narrative HPV vaccination intervention aimed at reaching college women: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Sci. 2012;13(2):173–82.

Marlow LA, Wardle J, Forster AS, Waller J. Ethnic differences in human papillomavirus awareness and vaccine acceptability. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(12):1010–5.

Marlow LA. HPV vaccination among ethnic minorities in the UK: knowledge, acceptability and attitudes. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(4):486–92.

Cunningham MS, Davison C, Aronson KJ. HPV vaccine acceptability in Africa: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2014;69:274–9.

Molokwu J, Fernandez NP, Martin C. HPV awareness and vaccine acceptability in hispanic women living along the US-Mexico border. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(3):540–5.

Constantine NA, Jerman P. Acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccination among Californian parents of daughters: a representative statewide analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(2):108–15.

Dahlstrom LA, Tran TN, Lundholm C, Young C, Sundstrom K, Sparen P. Attitudes to HPV vaccination among parents of children aged 12–15 years-a population-based survey in Sweden. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(2):500–7.

Ezeanochie MC, Olagbuji BN. Human papilloma virus vaccine: determinants of acceptability by mothers for adolescents in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2014;18(3):154–8.

Lu B, Kumar A, Castellsague X, Giuliano AR. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic vaccines against cervical HPV infection and diseases among women: a systematic review & meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:13.

Prygiel M, Janaszek-Seydlitz W. [Efficacy and safety of vaccines against human papillomavirus (HPV)]. Przegl Epidemiol. 2012;66(4):657–65.

Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, October 2014-Recommendations. Vaccine. 2015;33:4383.

Goncalves AK, Cobucci RN, Rodrigues HM, de Melo AG, Giraldo PC. Safety, tolerability and side effects of human papillomavirus vaccines: a systematic quantitative review. Braz J Infect Dis. 2014;18(6):651–9.

Macartney KK, Chiu C, Georgousakis M, Brotherton JM. Safety of human papillomavirus vaccines: a review. Drug Saf. 2013;36(6):393–412.

Kang S, Kim KH, Kim YT, Kim YT, Kim JH, Song YS, Shin SH, Ryu HS, Han JW, Kang JH et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a vaccine targeting human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16 and 18: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 176 Korean subjects. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18(5):1013–9.

Bhatla N, Suri V, Basu P, Shastri S, Datta SK, Bi D, Descamps DJ, Bock HL, Indian HPVVSG. Immunogenicity and safety of human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine in healthy Indian women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(1):123–32.

Khatun S, Akram Hussain SM, Chowdhury S, Ferdous J, Hossain F, Begum SR, Jahan M, Tabassum S, Khatun S, Karim AB. Safety and immunogenicity profile of human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04 adjuvant cervical cancer vaccine: a randomized controlled trial in healthy adolescent girls of Bangladesh. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42(1):36–41.

Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler C, Ferris DG, Jenkins D, Schuind A, Zahaf T, Innis B, Naud P, De Carvalho NS et al. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1757–65.

Reisinger KS, Block SL, Lazcano-Ponce E, Samakoses R, Esser MT, Erick J, Puchalski D, Giacoletti KE, Sings HL, Lukac S et al. Safety and persistent immunogenicity of a quadrivalent human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, 18 L1 virus-like particle vaccine in preadolescents and adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(3):201–9.

Lazcano-Ponce E, Perez G, Cruz-Valdez A, Zamilpa L, Aranda-Flores C, Hernandez-Nevarez P, Viramontes JL, Salgado-Hernandez J, James M, Lu S et al. Impact of a quadrivalent HPV6/11/16/18 vaccine in Mexican women: public health implications for the region. Arch Med Res. 2009;40(6):514–24.

Munoz N, Manalastas Jr R, Pitisuttithum P, Tresukosol D, Monsonego J, Ault K, Clavel C, Luna J, Myers E, Hood S et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, 18) recombinant vaccine in women aged 24–45 years: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1949–57.

Kim YJ, Kim KT, Kim JH, Cha SD, Kim JW, Bae DS, Nam JH, Ahn WS, Choi HS, Ng T et al. Vaccination with a human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine in Korean girls aged 10–14 years. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25(8):1197–204.

Medina DM, Valencia A, de Velasquez A, Huang LM, Prymula R, Garcia-Sicilia J, Rombo L, David MP, Descamps D, Hardt K et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: a randomized, controlled trial in adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(5):414–21.

Ngan HY, Cheung AN, Tam KF, Chan KK, Tang HW, Bi D, Descamps D, Bock HL. Human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine: immunogenicity and safety in healthy Chinese women from Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16(3):171–9.

Kim SC, Song YS, Kim YT, Kim YT, Ryu KS, Gunapalaiah B, Bi D, Bock HL, Park JS. Human papillomavirus 16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine: immunogenicity and safety in 15–25 years old healthy Korean women. J Gynecol Oncol. 2011;22(2):67–75.

Szarewski A, Poppe WA, Skinner SR, Wheeler CM, Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmeron J, Chow SN, Apter D, Kitchener H et al. Efficacy of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in women aged 15–25 years with and without serological evidence of previous exposure to HPV-16/18. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(1):106–16.

Rambout L, Tashkandi M, Hopkins L, Tricco AC. Self-reported barriers and facilitators to preventive human papillomavirus vaccination among adolescent girls and young women: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2014;58:22–32.

Pomfret TC, Gagnon Jr JM, Gilchrist AT. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: a review of safety, efficacy, and pharmacoeconomics. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36(1):1–9.

Chatterjee A, O’Keefe C. Current controversies in the USA regarding vaccine safety. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2010;9(5):497–502.

Black S, Rappuoli R. A crisis of public confidence in vaccines. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(61):61mr61.

Larson HJ, Cooper LZ, Eskola J, Katz SL, Ratzan S. Addressing the vaccine confidence gap. Lancet. 2011;378(9790):526–35.

Larson HJ, Smith DM, Paterson P, Cumming M, Eckersberger E, Freifeld CC, Ghinai I, Jarrett C, Paushter L, Brownstein JS et al. Measuring vaccine confidence: analysis of data obtained by a media surveillance system used to analyse public concerns about vaccines. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(7):606–13.

Poljak M. Prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccination and primary prevention of cervical cancer: issues and challenges. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18 Suppl 5:64–9.

Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, Trucks E, Hanchate A, Gorin SS. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine. 2015;33(9):1223–9.

Cohen EL, Head KJ. Identifying knowledge-attitude-practice gaps to enhance HPV vaccine diffusion. J Health Commun. 2013;18(10):1221–34.

Gough E, Kempf MC, Graham L, Manzanero M, Hook EW, Bartolucci A, Chamot E. HIV and hepatitis B and C incidence rates in US correctional populations and high risk groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:777.

Allen JD, Coronado GD, Williams RS, Glenn B, Escoffery C, Fernandez M, Tuff RA, Wilson KM, Mullen PD. A systematic review of measures used in studies of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptability. Vaccine. 2010;28(24):4027–37.

Acknowledgements

We thank the contributions to this study made in various ways by members of the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics and Shenzhen Maternity and Child Health Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YZ conducted the meta-analysis and drafted the manuscript. YW conceived the study and edited the manuscript. LL made substantial contributions to revising the manuscript. YF performed the detailed quality framework. ZL carried out the literature search and coding of original studies. YYW was involved in reviewing the articles and statistical analyses. SN conceived and designed the experiments, and supervised the study in all phases. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Availability of Data and Materials. (XLS 38 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, L. et al. Awareness and knowledge about human papillomavirus vaccination and its acceptance in China: a meta-analysis of 58 observational studies. BMC Public Health 16, 216 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2873-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2873-8