Abstract

Background

The assessment of changes in dietary habits provides interesting information on whether or not the observed trends are in line with accepted nutritional guidelines. The objective was to evaluate within-subject longitudinal changes in food consumption and nutrient intake and in a 10-year follow-up study.

Methods

The SUN (Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra) project is a prospective Spanish cohort study. Diet was assessed using a 136-item food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ), previously validated in Spain. The participants were 3036 university graduates (55.8 % women) of Spain and the main outcome measures the changes in dietary quality and in food consumption and nutrient intake. Paired t-tests and conditional logistic regression models were used to evaluate within-subject longitudinal dietary changes and the risk of inadequacy respectively, after 10 years of follow-up.

Results

During follow-up, participants showed a relevant and significant increase (p < 0.001) in the consumption of fruits (7.4 %), vegetables (8.6 %), low-fat dairy products (35.2 %), lean meat (12.4 %), fish (2.9 %), whole grains (53.2 %), nuts (52.4 %) and a significant decrease in legumes (−7.4 %), whole-fat dairy products (−44.2 %), red meat (−17.6 %), sugar-sweetened beverages (−58.7 %) and wine (−11.9 %). With respect to nutrients, we found a higher proportion of carbohydrates (3.6 %) and fiber (7.4 %) and a decrease in total energy intake (2.7 %), total fat (−4.5 %), SFA (−9.4 %), MUFA (−4.9 %), PUFA (−12.7 %), w-3 and w-6 fatty acids (−9.1 and −20.5 % respectively) and cholesterol (−9.6 %).

Conclusions

In this Mediterranean cohort study, mainly beneficial changes in the consumption of most foods and macronutrients were observed after 10 years of follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nutritional adequacy implies sufficient intake of essential nutrients needed to meet nutritional requirements not only for optimal health, but also for the prevention of nutrient-deficiency diseases as well as chronic diseases [1]. Mediterranean diet is a dietary pattern with high nutritional adequacy including a healthy profile of fat intake, low glycemic index and high content of dietary fiber. Moreover, the Mediterranean diet has been proposed to be used in public health nutrition policies in order to prevent micronutrient deficiencies [2–5].

Trends in food consumption and nutrient intake assessment are essential for re-evaluating dietary guidelines. Epidemiological research confirms that the prevalence of suboptimal micronutrient intakes across Europe is an emerging concern in terms of public health [6]. In fact, previous investigations have reported trends in food consumption and dietary habits [7–12], nutrient intake [13–19] in prospective cohorts participants, showing disparities in diet quality change. In general, trends seem to be in the direction to a healthier diet.

In Spain, energy and nutrient intakes of adult population have markedly changed in the last 40 years and now, dietary habits differ from the traditional Mediterranean diet according to the nationwide representative Food Consumption Survey for the period 2000–2012 [20].

The Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) is a prospective cohort mainly constituted by health care professionals [21] (54.5 % of participants), who are regularly assessed for their dietary habits. Participation in a cohort study may probably affect the eating habits of participants. The higher educational level of this cohort may influence dietary habits. A recent systematic review provides evidence of positive, although weak, association between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake [22]. An important exemplary role in the adoption or departure from healthy eating patterns is played by some sectors of the population with higher levels of education, whose lifestyles are eventually adopted also by the rest of the society. In addition, health professionals have the potential to provide nutrition care that improves the nutrition behaviour and risk factors in individuals with lifestyle-related chronic disease [23]. Furthermore, health professionals with healthy habits are more committed to promoting healthy behaviours than those with unhealthy lifestyles regarding smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity or weight management [24, 25]. But despite being educated in health promotion practice, health professionals’ behaviours, including dietary intake, may not be exemplary [26].

From this point of view it is interesting to assess trends in dietary intakes and food patterns in this Mediterranean cohort of Spanish university graduates. However, there are not epidemiological studies that have shown changes in food consumption in longitudinal Mediterranean cohort studies which provide evidence of variations in subjects who can be revisited on several occasions.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to address the change in diet in a Mediterranean cohort. The aims of this work were to evaluate within-subject longitudinal changes in food consumption and nutrient intakes and also to compare nutritional inadequacy after 10 years of follow up. Our hypothesis was that certain improvements in dietary quality should be expected because of the social influence that nutritional epidemiology may have exerted in the Spanish population, especially in its best educated sectors, and also because of the voluntary long-term participation of the assessed university graduates in an epidemiological cohort.

Methods

Study population

The objectives, design, and methods of the SUN project have been described elsewhere [21, 27]. The SUN project is a multipurpose, dynamic cohort designed to assess the association between diet and several chronic diseases and health conditions. It was developed following the models of the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. The recruitment of participants started in December 1999 and it is permanently open. After the initial questionnaire, additional questionnaires are mailed every 2 years in order to follow-up the participants.

Participants who completed a baseline Food-Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ_0) and the same FFQ after 10 years of follow-up (FFQ_10) were eligible for these longitudinal analyses (n = 4218). Participants in the SUN study who were recruited less than 10 years before the closing date of December 1, 2,013 (n = 21705), those who failed to complete the 10-y assessment (n = 16818) and those who completed the 10-y assessment but did not answer the FFQ (n = 669) could not be included in our analyses. Among the available 4218 participants, we excluded those with extreme values for total energy intake in FFQ_0 or FFQ_10 (<800 or >4000 kcal/day for men and <500 or >3500 kcal/day for women) (n = 324) [28] and those who were outside of predefined values of any micronutrient intake in FFQ_0 and FFQ_10 (3 or more standard deviations from both sides of the mean) (n = 858). Finally, data from 3076 participants were included in our analyses.

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Navarra. We considered a response to the initial questionnaire as informed consent to participate in the study.

Assessment of dietary exposure

Dietary habits at baseline were assessed using a FFQ with 136 items, previously validated in Spain [29, 30]. This questionnaire assessed food habits in the previous year. There were nine possible answers (ranging from never/almost never to 6+ times per day). The questionnaire was semi-quantitative, i.e., for each food, a standard portion size was specified. Nutrient intake was calculated by multiplying the frequency of consumption by the nutrient content of the specified portion, using data from Spanish food composition tables [31, 32]. Furthermore, the average intake of micronutrients from dietary supplements was added to the intake from foods, taking into account the consumption declared over the past year.

We evaluated at baseline and after 10 years of follow-up, the intakes of Zn, I, Se, Fe, Ca, K, P, Mg, Cr and vitamins B1, B2, B3, B6, B12, C, A, D, E and folic acid, as well as the consumption of 15 selected foods (g/d) and adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern. Besides, we calculated nutrient (mg or μg/1000 kcal) and food density (g/1000 kcal) in FFQ_0 and FFQ_10. Only for those nutrients or foods with higher percentage of change in 10 years of follow-up, we study their changes according to the year of baseline questionnaire to evaluate temporal trends in changes of each dietary variable.

The prevalence of inadequate intake of macronutrients was studied comparing to national nutritional objectives of Spanish Society of Community Nutrition (2011) [33]. For vitamins or minerals, the probability of intake adequacy was calculated by comparing the intakes of these micronutrients with the estimated average requirements (EAR) when these were available or adequate intake levels, if not, as proposed by the Institute of Medicine [34]. On the other hand, intake adequacy for sixteen micronutrients (all, but Cr, K and Fe) was also evaluated using the probabilistic approach [35].

Finally, adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern was assessed by a priori 9-point Mediterranean-diet scale as proposed by Trichopoulou et al. that incorporated the salient characteristics of this diet (range of scores, 0 to 9, with higher scores indicating greater adherence) [36].

We repeated the analyses after excluding those participants who consumed dietary supplements baseline and after 10-years of follow-up (n = 1028). Analyses were also stratified by sex because of potential differences in nutrient intake and food consumption between two groups. We also compared health professionals versus non-health professionals.

Assessment of other variables

The baseline questionnaire also collected information on a wide array of characteristics, including socio-demographic variables, health-related habits, and clinical variables.

We assessed physical activity at baseline using a previously validated questionnaire in Spain which included information about 17 activities [37]. The time spent in different activities was multiplied by the MET (Metabolic Equivalent Score) specific to each activity, and then the MET score were summed over all activities to obtain a value of overall weekly MET hours.

Statistical analysis

We described the baseline characteristics of participants using means (SD) or percentages for each variable. To evaluate within-subject longitudinal changes in food consumption and nutrient intake after 10 years of follow-up we used paired Student’s t test. Within-group differences are expressed as means and 95 % confidence intervals (CI).

To compare paired proportions of prevalence of inadequate intake we used conditional logistic regression. Odds Ratios (OR) (95 % CI) were calculated for each nutrient’s or food inadequate intake at 10-years of follow-up versus inadequate intake at baseline. Stratified analyses were performed to assess whether the professional group (health professional versus non-health professionals) or sex modified this association. In sensitivity analyses we excluded participants who used dietary supplements at baseline or after 10-years of follow-up.

Analyses were performed with STATA version 12 (STATA Corp., TX, USA). All P values are two-tailed and statistical significance was set at the conventional cut-off of P <0.05.

Results and discussion

The baseline and 10 years characteristics of the 3036 participants in the SUN cohort with enough follow-up time and available data after 10 years are summarized in Table 1. After 10 years follow-up, the prevalence of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, dietary supplement use, following a special diet, and Mediterranean diet adherence were higher than at baseline, whereas a decrease in smoking rate was observed during follow - up.

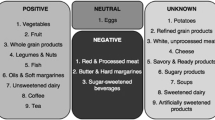

Changes in selected food consumption and macronutrient intake from baseline to ten of years of follow-up are shown in Table 2. Participants showed a significant (p < 0.001) increase in the consumption of fruits (+21.1 g/d), vegetables (+39.7 g/d), low-fat dairy (+58.6 g/d), lean meat (+5.3 g/d), fish (+2.5 g/d), whole grains (+5.0 g/d), refined grains (+5.7 g/d) and nuts (+3.3 g/d). Reductions in the consumption of legumes (−1.6 g/d), whole-fat dairy products (−100.6 g/d), red meat (−14.6 g/d), sugar-sweetened beverages (−28.8 g/d) and wine (−3.5 g/d), were also observed. With respect to energy and macronutrient distribution, the most relevant changes were found in a higher proportion of energy from carbohydrates (1.5 % E), increased fiber intake (+1.8 g/d), and a decrease in total energy intake (−62.0 kcal/d), total fat proportion (−1.7 % E) and dietary cholesterol intake (−39.3 mg/d).

The consumption of whole-fat dairy products (−44.2 %), red meats (−17.6 %), sugared-sweetened beverages (−58.7 %) and wine (−11.9 %) had shown marked decreases after 10 years of follow-up, while the consumption of low-fat dairy products (35.2 %), lean meat (12.4 %), whole grains (53.2 %), nuts (52.4 %) and alcohol (47.8 %) showed an important increasing trend (Table 2). With respect to nutrient intake, we found a decrease in total fat (−4.5 %), SFA (−9.4 %), MUFA (−4.9 %), PUFA (−12.7 %), w-3 (−9.1 %) and w-6 fatty acids (−20.5 %) and cholesterol intakes (−9.6 %) and an increase in carbohydrates (3.6 %) and fiber (7.4 %).

Table 3 shows changes in micronutrient and food density referring to 1000 kcal. After 10 years of follow-up, participants showed a significant (p < 0.001) increase in nutritional density of Zn (+1.3 mg/1000 kcal), Fe (+0.2 mg/1000 kcal), K (+77.4 mg/1000 kcal), Mg (+9.5 mg/1000 kcal), vitamin B3 (+0.2 mg/1000 kcal), vitamin B6 (+0.08 mg/1000 kcal), vitamin C (+9.8 mg/1000 kcal), vitamin A (+66.2 μg/1000 kcal) and folic acid (+14.9/1000 kcal). We only observed a significant decrease in nutritional density of iodine (−7.0 μg/1,000 kcal) and vitamin B12 (−0.3 μg/1,000 kcal). With respect to changes in selected food density referring to 1000 kcal, trends were similar than observed changes in g/d.

The percentage of participants who increased (to any extent) their consumption of several food groups during 10-years of follow-up is presented in Fig. 1. Participants were more likely to exhibit the following favorable dietary changes: an increase in the consumption of fruits, vegetables, fish and low-fat dairy products and a reduction in the consumption of whole fat dairy, red meats, sugared-sweetened beverages and wine.

On the other hand, the change in dietary variables was also assessed regarding the year of baseline questionnaire (Fig. 2). With respect to food consumption, changes in sugared-sweetened beverages, whole and low-fat dairy were higher among participants who were recruited in the first years of the SUN project (1999/2000), while the increase in nuts consumption was higher among subjects who entered in the cohort in 2003 than in 1999/2000.

Finally, with respect to nutrient intake, the higher changes after 10-year follow-up were observed for cholesterol, w-6 and w-3 fatty acids, PUFA, SFA and fiber (Fig. 3). For all these dietary variables, except for fiber, we observed reductions in intake as compared to baseline, although the higher decreases were mainly among participants who were recruited in 1999/2,000 or 2001 (p for trend in all variables < 0.001).

Finally, we calculated the risk of inadequate nutrient intake after 10 years of follow-up. Significant increases in the percentage of participants with intakes under the EAR at 10-years of follow-up versus intake at baseline was found for vitamin E, w-6 and w-3 fatty acids, I, Se, MUFA and Ca. On the other hand, the percentage of non-compliers with the national nutritional objectives or EAR values was lower at 10-years of follow-up for adherence to the Mediterranean dietary score, cholesterol, vitamin C and fiber (data not shown).

We repeated the analyses after excluding participants who used dietary supplements at baseline or after 10-years of follow-up and stratified by profession at baseline (health professional versus non-health professionals) or by sex. In general, findings in the three sensitivity analyses supported the robustness of our main findings (data not shown).

In the present study, we investigated changes in nutrient intake and food consumption in a cohort of university graduates over a period of 10 years. To our knowledge, this is the first study to present data on change in dietary composition and quality over an extended period of time in participants of a large cohort of adults in a Mediterranean country.

In our sample, the proportion of participants consuming dietary supplements and following special diets has increased, although it is considerably lower comparing to published data from other cohorts [38, 39]. Regarding dietary supplements, a recent review [40], showed that prevalence of use increase with age, and dietary supplement users tend to be better educated and have higher health-consciousness. In general, the reasons most often cited for supplement use are overall health and wellness to fill nutrient gap in their diet [41]. According to the latest National Health Survey in Spain in 2012 [42], the prevalence of following a special diet in the adult population was between 8.1–12.6 %, similar to our results. On the other hand, we observed a moderate increase of BMI and in the percentage of former smokers after 10 years of follow-up. This increase might be explained by several health interventions in last decades (smoke-free policies, price increases, and mass media campaigns) [43]. Finally, we found also an increase in the prevalence of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia mainly because of the ageing of the cohort. Age is a well-known risk factor for the development of these diseases [44, 45].

We observed significant and positive changes in plants foods, in particular in the consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and in low-fat dairy and lean meats, whereas the consumption of some foods, that could be considered unhealthy, including whole fat dairy, red meats and sugared-sweetened beverages, decreased. We also found a significant decrease in energy intake, percentage of energy from fat, SFA, MUFA, PUFA, essential fatty acids and cholesterol, and an increase in carbohydrates and fiber intakes as well as a greater adherence to the Mediterranean Diet after 10 years of follow-up.

Previous research in Spain has provided evidence of trends in energy and nutrient intake during past decades using household consumption surveys [46, 47], food consumption survey [20] or regional nutritional surveys [48–54]. However, none of those previous studies assessed the same individuals with repeated measurements of diet along the follow-up time.

In Spain, trends highlight a reduction in food sources of animal fats, especially the preference observed for low fat or fat-free dairy products in place of whole-milk derivatives [51]. A similar decline has been found in dairy products, legumes, white bread and wine, which have being gradually replaced by beer, and the increase in vegetable and fruits consumptions [20, 47]. Furthermore, the mean energy intake and the percentage of energy from carbohydrates were clearly lower than several decades before [20]. In this sense, the Spanish diet currently differs somewhat from the traditional and healthy Mediterranean diet [20, 47].

Worldwide, few studies have specifically examined longitudinal intra-individual changes in diet quality in adult and that have compared these changes with the national dietary recommendations [8, 11–17, 19]. In general terms, these cohorts have also shown improvements in food patterns, as we found in our investigation. In a Danish cohort with 2430 individuals aged 30–70 years, the main ten-year trend (1982–1984/1992–1994) in dietary habits was a decreased consumption of meat products, white bread and an increased consumption of fruit and raw vegetables among other foods [12]. Similarly, the CARDIA study, over 20 years of observation in participants aged 18–30 years, reported an increase in the dietary quality scores and in the consumption of plant foods, lean meat and low-fat dairy products, whereas the consumption of fried potatoes, soft drinks, high-fat dairy and red meat decreased [17].

The dietary habits of participants in the Finnish cohort of the MONICA study improved between 1982 and 1992 and showed continued but less pronounced improvement between 1992 and 2003. There was a reduction in the consumption of butter, high-fat milk products, eggs and sugar and an increase in the consumption of vegetable oils in cooking, low-fat and fat-free milk products. Overall, change was generally in a positive direction [8]. Finally, several investigations about changes in diet and profile of energy and nutrient intakes in British birth cohort over 8 or 17 years, suggested that most of the trends observed are in line with the accepted dietary guidelines and with our results, such as the increased consumption of fruit and vegetable and a shift away from whole milk and red meat [11, 13, 19]. By contrast, our results were discrepant with the findings of the Melbourne Chinese Cohort Study [14] and in the Framingham Heart Study Offspring Cohort [15, 16], in relation to the consumption of foods rich in animal, the percentage of energy derived from fat, proteins and carbohydrates.

Moreover, we should take into account that quantitative comparisons with studies from other European countries or regions are difficult and their interpretation requires caution for several reasons. Among these reasons, the surveys were conducted with different samples or periods, evaluated distinct periods of follow-up and differences in methods for assessing dietary intakes. All these facts, limit direct comparisons.

Several factors may contribute to explain the reported favourable changes in the overall diet quality between 1999–2003 and 2010–2013 in this Mediterranean adult cohort. It is possible that SUN participants were particularly aware of their food habits and perhaps indirectly tried to improve them because of administered FFQ assessment or their participation in a longitudinal study. However, the SUN project is an observational study where participants receive every two years a self-administered general questionnaire, but the full-length FFQ is self-administered only twice along the study, at baseline and after 10 years of follow-up. Therefore, participants in the SUN cohort do not have any direct contact with an interviewer did not receive individualized dietary advice. Another potential explanation may be related to the increased availability of scientific evidence and the media impact of nutritional epidemiology. The every-other year bulletins that participants receive giving them feedback on the study, including also the results of the main published papers with their data- may have contributed to improve the dietary habits of participants. Most of these positive changes could also be attributed to improvements in food availability, nutrition policy, and an increased public awareness of the association between diet and chronic diseases or to the process of ageing. Another possible reason is that many of the observed changes in diet over the 10-year period were in line with many current population dietary recommendations, such as the 5-a-day plan for vegetables and fruits, as well as traditional recommendations, such as increasing fiber and decreasing fat in our diet [33]. Thus, for example, our participants reduced their whole-fat dairy and sugared-sweetened beverage consumption, while they increased their consumption of low-fat and skimmed milk and whole grain products. These changes could be, in part, a consequence of a higher degree of compliance with the last Spanish dietary guidelines that emphasised the importance of preferring low-fat dairy and whole grains and moderating sugar intake. In fact, according to a recent study, the proportion of Spanish adults complying with the nutritional objectives for consumption of dietary fiber, folic acid, SFA, cholesterol, carbohydrate, and fruit has increased from 2000 to 2010 [48]. Another explanation is that during the past decade, educational strategies have tended to shift from nutrients to an overall dietary pattern, with specific attention on varied consumption and on the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet. Thus, the public emphasis on healthier dietary patterns developed during the period under study may at least partially explain the increase in most characteristic ingredients in our participants. In addition, our participants had higher education level than the average population, since all of them were university graduates, and therefore could be faster than other sector in taking the public health messages up.

Our study has the following strengths. This is the first study, to our knowledge, measuring within the same participants with repeated measurements changes in food consumption and nutrient intake and inadequacy, among a large Mediterranean sample during a long follow-up period. Other strengths are the prospective design which avoids reverse causation bias present in cross-sectional studies, the large sample size, the high response rate and the high educational level of participants, which allows for a better understanding of the FFQ, the large follow-up period, the previous validation of the methods used to assess the dietary intake [29, 30] and the use of a wide range of scoring for each food portion (9 categories) in the FFQ.

However, our findings must be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitations. First, our sample was small. However, among participants with 10 years of follow-up (n = 8245), 4887 filled the general questionnaire by internet, and among them, 4218 completed the 10-year full-length FFQ. Second, we used a self-reported FFQ to assess dietary exposure, which has measurement errors and might not be the best method to assess the intake of some micronutrients (e.g. Se, Fe and folic acid). In any case, in large epidemiological studies, the FFQ is the most practical and feasible tool to evaluate diet outcome [55]. Besides, there was a difference in the way to fill the FFQ_0 (paper) and the FFQ_10 (by internet), that could introduce a systematic error in our results. However, they contain exactly the same items and portions. Third, the SUN cohort only includes university graduates and its sample is not representative of the general Spanish population. This characteristic may affect the generalizability of our findings to other groups of individuals or to other populations. However, it could also have actually enhanced its internal validity because the high level of education and the homogeneity of socioeconomic status of participants reduced the potential confounding. Fourth, it is possible that SUN participants were particularly aware of their diet because of general study participation and the administration of dietary recall methods, which resulted in improvements of their dietary habits (Hawthorne effect). However, although the bias toward nutrition-conscious participants is a well-known problem in volunteer participants, most of our observed changes were minimal and some of them were even contrary to expectations, such as the apparent decrease in legume consumption. Fifth, the total dietary intake of micronutrients could be probably underestimated, as we calculated the average intake of micronutrients including the intake from foods and from dietary supplements, but without considering the intake from medication that participants might be consuming or from fortified foods, hardly included in the food composition tables. Sixth, we used two of the most important Spanish food composition tables to translate food frequency consumption into micronutrient intakes, which might be a source of variation in our results. Seventh, we could not identify changes due to consumer choices, food composition and those that are inherent in the study methodology. However, although it is difficult to separate clearly all these changes and they may have occurred in parallel. Finally, as in any observational study, potential residual confounding could not be ruled out.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the changes in specific food groups generally supported a change to improved diet quality and in line with recommendations by health promotion messages, although other changes suggest the opposite, and perhaps additional strategies will be needed. This study suggests that dietary intake is changeable and that disease prevention measures can be implemented in adulthood. More evidence from studies that assess changes in dietary quality in longitudinal studies is required to corroborate these findings or to evaluate determinants of dietary changes. The SUN study provides a unique opportunity in a Mediterranean country to investigate whether the nutrient intake of individuals changes significantly during adult life. Finally, observational studies always imply a minimal degree intervention that contribute to improve the dietary habits and lifestyle of participants.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CI:

-

Confidence Intervals

- EAR:

-

Estimated Average Requirements

- FFQ:

-

Food Frequency Questionnaire

- FFQ_0:

-

Baseline Food Frequency Questionnaire

- FFQ_10:

-

Food Frequency Questionnaire after ten years of follow-up

- MET:

-

metabolic equivalent

- OR:

-

odds ratios

- SUN:

-

Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra

References

Claessens M, Contor L, Dhonukshe-Rutten R, De Groot LC, Fairweather-Tait SJ, Gurinovic M, et al. EURRECA-Principles and future for deriving micronutrient recommendations. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2013;53:1135–46.

Maillot M, Issa C, Vieux F, Lairon D, Darmon N. The shortest way to reach nutritional goals is to adopt Mediterranean food choices: evidence from computer-generated personalized diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:1127–37.

Castro-Quezada I, Roman-Viñas B, Serra-Majem L. The Mediterranean diet and nutritional adequacy: a review. Nutrients. 2014;6:231–48.

Serra-Majem L, Bes-Rastrollo M, Román-Viñas B, Pfrimer K, Sánchez-Villegas A, Martínez-González MA. Dietary patterns and nutritional adequacy in a Mediterranean country. Br J Nutr. 2009;10 Suppl 2:S21–8.

Zazpe I, Sánchez-Taínta A, Santiago S, de la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Bes-Rastrollo M, Martínez JA, et al. Association between dietary carbohydrate intake quality and micronutrient intake adequacy in a Mediterranean cohort: the SUN (Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra) Project. Br J Nutr. 2014;25:1–10.

Roman Viñas B, Ribas Barba L, Ngo J, Gurinovic M, Novakovic R, Cavelaars A, et al. Projected prevalence of inadequate nutrient intakes in Europe. Ann Nutr Metab. 2011;59:84–95.

Siega-Riz AM, Sotres-Alvarez D, Ayala GX, Ginsberg M, Himes JH, Liu K, et al. Food-group and nutrient-density intakes by Hispanic and Latino backgrounds in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:1487–98.

Haapala I, Prättälä R, Patja K, Männikkö R, Hassinen M, Komulainen P, et al. Age, marital status and changes in dietary habits in later life: a 21-year follow-up among Finnish women. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:1174–81.

Pan A, Sun Q, Bernstein AM, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in red meat consumption and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: three cohorts of US men and women. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1328–35.

Wrieden WL, Connaghan J, Morrison C, Tunstall-Pedoe H. Secular and socio-economic trends in compliance with dietary targets in the north Glasgow MONICA population surveys 1986–1995: did social gradients widen? Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:835–42.

Parsons TJ, Manor O, Power C. Changes in diet and physical activity in the 1990s in a large British sample (1958 birth cohort). Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:49–56.

Osler M, Heitmann BL, Schroll M. Ten year trends in the dietary habits of Danish men and women. Cohort and cross-sectional data. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997;51:535–41.

Prynne CJ, Paul AA, Mishra GD, Greenberg DC, Wadsworth ME. Changes in intake of key nutrients over 17 years during adult life of a British birth cohort. Br J Nutr. 2005;94:368–76.

Zhang H, Hsu-Hage BH, Wahlqvist ML. Longitudinal changes in nutrient intakes in the Melbourne Chinese Cohort Study. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:433–9.

Makarem N, Scott M, Quatromoni P, Jacques P, Parekh N. Trends in dietary carbohydrate consumption from 1991 to 2008 in the Framingham Heart Study Offspring Cohort. Br J Nutr. 2014;24:1–14.

Vadiveloo M, Scott M, Quatromoni P, Jacques P, Parekh N. Trends in dietary fat and high-fat food intakes from 1991 to 2008 in the Framingham Heart Study participants. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:724–34.

Sijtsma FP, Meyer KA, Steffen LM, Shikany JM, Van Horn L, Harnack L, et al. Longitudinal trends in diet and effects of sex, race, and education on dietary quality score change: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:580–6.

Batis C, Sotres-Alvarez D, Gordon-Larsen P, Mendez MA, Adair L, Popkin B. Longitudinal analysis of dietary patterns in Chinese adults from 1991 to 2009. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1441–51.

Almoosawi S, Winter J, Prynne CJ, Hardy R, Stephen AM. Daily profiles of energy and nutrient intakes: are eating profiles changing over time? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:678–86.

Varela-Moreiras G, Ruiz E, Valero T, Avila JM, del Pozo S. The Spanish diet: an update. Nutr Hosp. 2013;28 Suppl 5:13–20.

Seguí-Gómez M, de la Fuente C, Vázquez Z, de Irala J, Martínez-González MA. Cohort profile: the ‘Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra’ (SUN) study. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:1417–22.

Spronk I, Kullen C, Burdon C, O’Connor H. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1713–26.

Ball L, Johnson C, Desbrow B, Leveritt M. General practitioners can offer effective nutrition care to patients with lifestyle-related chronic disease. J Prim Health Care. 2013;5:59–69.

Bakhshi S, While AE. Health professionals’ alcohol-related professional practices and the relationship between their personal alcohol attitudes and behaviour and professional practices: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:218–48.

Zhu DQ, Norman IJ, While AE. The relationship between doctors’ and nurses’ own weight status and their weight management practices: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2011;12:459–69.

Blake H, Harrison C. Health behaviours and attitudes towards being role models. Br J Nurs. 2013;22:86–94.

Martínez-González MA, Sanchez-Villegas A, De Irala J, Marti A, Martínez JA. Mediterranean diet and stroke: objectives and design of the SUN Project. Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra. Nutr Neurosci. 2002;5:65–73.

Willett W. Issues in analysis and presentation of dietary data. In: Willet W, editor. Nutritional Epidemiology, ed 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. p. 322.

Martin-Moreno JM, Boyle P, Gorgojo L, Maisonneuve P, Fernandez-Rodriguez JC, Salvini S, et al. Development and validation of a food frequency questionnaire in Spain. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22:512–9.

Fernández-Ballart JD, Piñol JL, Zazpe I, Corella D, Carrasco P, Toledo E, et al. Relative validity of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire in an elderly Mediterranean population of Spain. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:1808–16.

Mataix Verdú J. Tabla de composición de alimentos españoles (Spanish Food Composition Table), ed 3. Universidad de Granada: Granada; 2003.

Moreiras O, Carbajal A, Cabrera L. Tablas de composición de alimentos (Food Composition Tables), ed 9. Madrid: Pirámide; 2005.

Aranceta J, Serra-Majem L, SENC Working Group. Objetivos nutricionales para la población española. Rev Esp Nutr Comunitaria. 2011;17:178–99.

Institute of Medicine Food Nutrition Board. Dietary reference intakes: applications in dietary assessment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

Anderson GH, Peterson RD, Beaton GH. Estimating nutrient deficiencies in a population from dietary records: the use of probability analyses. Nutr Res. 1982;2:409–15.

Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2599–608.

Martínez-González MA, López-Fontana C, Varo JJ, Sánchez-Villegas A, Martinez JA. Validation of the Spanish version of the physical activity questionnaire used in the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals’ Follow-up Study. Public Health Nutr. 2000;8:920–7.

Lentjes MA, Welch AA, Luben RN, Khaw KT. Differences in dietary supplement use and secular and seasonal trends assessed using three different instruments in the EPIC-Norfolk population study. J Diet Suppl. 2013;10(2):142–51.

Rautiainen S, Lee IM, Rist PM, Gaziano JM, Manson JE, Buring JE, et al. Multivitamin use and cardiovascular disease in a prospective study of women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(1):144–52.

Dickinson A, MacKay D. Health habits and other characteristics of dietary supplement users: a review. Nutr J. 2014;6(13):14.

Dickinson A, Blatman J, El-Dash N, Franco JC. Consumer usage and reasons for using dietary supplements: report of a series of surveys. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33(2):176–82.

Spanish National Health Survey 2011–2012. Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. Available at: http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/encuestaNacional/encuesta2011.htm

Midlöv P, Calling S, Sundquist J, Sundquist K, Johansson SE. The longitudinal age and birth cohort trends of smoking in Sweden: a 24-year follow-up study. Int J Public Health. 2014;59(2):243–50.

Ibrahim MM, Damasceno A. Hypertension in developing countries. Lancet. 2012;380(9841):611–9.

Anderson TJ, Mancini GB, Genest Jr J, Grégoire J, Lonn EM, Hegele RA. The new dyslipidemia guidelines: what is the debate? Can J Cardiol. 2015;31(5):605–12.

Moreno LA, Sarría A, Popkin BM. The nutrition transition in Spain: a European Mediterranean country. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:992–1003.

Bach-Faig A, Fuentes-Bol C, Ramos D, Carrasco JL, Roman B, Bertomeu IF, et al. The Mediterranean diet in Spain: adherence trends during the past two decades using the Mediterranean Adequacy Index. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:622–8.

Del Mar BM, Salas R, Coll JL, Pons A, Tur JA. Ten-year trends in compliance with the current Spanish nutritional objectives in Balearic Islands adult population (2000–2010). Nutrition. 2014;30:800–6.

Aranceta J, Pérez Rodrigo C, Eguileor I, Marzana I, González de Galdeano L, Saenz de Buruaga J. Food consumption patterns in the adult population of the Basque Country (EINUT-I). Public Health Nutr. 1998;1:185–92.

Tur JA, Romaguera D, Pons A. Food consumption patterns in a Mediterranean region: does the Mediterranean diet still exist? Ann Nutr Metab. 2004;48:193–201.

Ribas-Barba L, Serra-Majem L, Salvador G, Castell C, Cabezas C, Salleras L, et al. Trends in dietary habits and food consumption in Catalonia, Spain (1992–2003). Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:1340–53.

Serra-Majem L, Ribas-Barba L, Salvador G, Jover L, Raidó B, Ngo J, et al. Trends in energy and nutrient intake and risk of inadequate intakes in Catalonia, Spain (1992–2003). Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:1354–67.

Serra-Majem L, Ribas-Barba L, Salvador G, Serra J, Castell C, Cabezas C, et al. Compliance with dietary guidelines in the Catalan population: basis for a nutrition policy at the regional level (the PAAS strategy). Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:1406–14.

Bondia-Pons I, Serra-Majem L, Castellote AI, López-Sabater MC. Compliance with the European and national nutritional objectives in a Mediterranean population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61:1345–51.

Satija A, Yu E, Willett WC, Hu FB. Understanding nutritional epidemiology and its role in policy. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:5–18.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants of the SUN cohort for their continuously involvement in the project and all members of the SUN study for their support and collaboration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) Project has received funding from the Spanish Ministry of Health and European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) (Grants PI10/02993, PI10/02658,PI13/00615, PI14/01668, PI14/01798, PI14/01764, RD06/0045,G03/140), the Navarra Regional Government (45/2011, 122/2014),and the University of Navarra.

Funding sources had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of results, and in the writing of the manuscript. All authors were and are independent from funders. None of the authors had any personal or financial conflict of interest.

Authors’ contribution

CDA, MBR and MAMG helped design the study and collected the data. CDA, IZ, SS, MBR and MAMG analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. MRB, MRC, AG and MAMG edited and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

de la Fuente-Arrillaga, C., Zazpe, I., Santiago, S. et al. Beneficial changes in food consumption and nutrient intake after 10 years of follow-up in a Mediterranean cohort: the SUN project. BMC Public Health 16, 203 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2739-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2739-0