Abstract

Background

Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, particularly for respiratory tract infections (RTI) in ambulatory care, has become a worldwide public health threat due to resulting antibiotic resistance. In spite of various interventions and campaigns, wide variations in antibiotic use persist between European countries. Cultural determinants are often referred to as a potential cause, but are rarely defined. To our knowledge, so far no systematic literature review has focused on cultural determinants of antibiotic use. The aim of this study was to identify cultural determinants, on a country-specific level in ambulatory care in Europe, and to describe the influence of culture on antibiotic use, using a framework of cultural dimensions.

Method

A computer-based systematic literature review was conducted by two research teams, in France and in Norway. Eligible publications included studies exploring antibiotic use in primary care in at least two European countries based on primary study results, featuring a description of cultural determinants, and published between 1997 and 2015. Quality assessment was conducted independently by two researchers, one in each team, using appropriate checklists according to study design. Each included paper was characterized according to method, countries involved, sampling and main results, and cultural determinants mentioned in each selected paper were extracted, described and categorized. Finally, the influence of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions associated with antibiotic consumption within a primary care setting was described.

Results

Among 24 eligible papers, 11 were rejected according to exclusion criteria. Overall, 13 papers meeting the quality assessment criteria were included, of which 11 used quantitative methods and two qualitative or mixed methods. The study participants were patients (nine studies) and general practitioners (two studies). This literature review identified various cultural determinants either patient-related (illness perception/behaviour, health-seeking behaviour, previous experience, antibiotic awareness, drug perception, diagnosis labelling, work ethos, perception of practitioner) or practitioner-related (RTI management, initial training, antibiotic awareness, legal issues, practice context) or both (antibiotic awareness).

Discussion and Conclusion

Cultural factors should be considered as exerting an ubiquitous influence on all the consecutive stages of the disease process and seem closely linked to education. Interactions between determinant categories, cultural dimensions and antibiotic use in primary care are multiple, complex and require further investigation within overlapping disciplines. The context of European projects seems particularly relevant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Increasing antibiotic resistance due to inappropriate antibiotic prescription is a worldwide public health threat [1] which, according to the first WHO report in 2014 on the subject, could lead to a post-antibiotic era during the 21st century [2]. The highest rates of antibiotic prescriptions are observed in primary care for respiratory tract infections (RTI) [1]. A large number of international and national studies have explored various aspects of this situation. In addition, campaigns targeting the general public, aiming to raise awareness of appropriate antibiotic use and of the dangers linked to antimicrobial resistance, have been carried out in several countries, as well as interventions targeting practitioners and other health professionals, with varying results [3]. In spite of all these initiatives, the differences in surveyed antibiotic consumption [4] and related antimicrobial resistance rates [5] between European countries remain considerable and persistent over the years.

The multiple reasons for these differences are not fully understood. Various determinants of antibiotic prescription have been suggested in the literature and cultural factors are often referred to as possible explanations of persistent differences in antibiotic consumption between countries. Harbarth and Monnet [6] published an overview of determinants that could explain differences in antibiotic use, which included cultural factors. They also highlighted the importance of conducting further research, in particular to clarify the influence of cultural and socioeconomic determinants to guide interventions targeting appropriate antibiotic use.

According to the MeSH thesaurus culture is defined as a collective expression for all behaviour patterns acquired and socially transmitted through symbols. Cultural dimensions have been identified by different authors such as Hofstede [7], Hampden-Turner, Trompenaars [8] and Schwartz [9] as a model to better understand and measure cultural differences using various developed tools [10]. Various tools have been developed to measure and quantify cultural dimensions. One of the most popular approaches is based on the extensive work conducted by Geert Hofstede a Dutch sociologist. He defined and described initially four different cultural dimensions [11]: Power distance (PD), which measures the way society treats inequality between individuals, Uncertainty avoidance (UA), measuring the way the society deals with the uncertainty linked to the future, Individualism versus collectivism (IC), which measures the link between an individual and his/her group, and Masculinity versus femininity (MF), which measures how gender roles are distributed in a society. A database was created where scores for each country and each cultural dimension could be quantified and compared between countries [11] as well as correlated to other variables such as antibiotic consumption [12, 13].

Different levels of cultural identity can be considered within a society (family, neighbourhood, school, youth groups, workplace, community etc.). A focus on country-specific culture in Europe appeared the most relevant for this study, considering the fact that interventions, campaigns, surveillance of antibiotic consumption and resistance as well as numerous European projects tackling the problem of bacterial resistance have all been conducted on a national scale within the European context.

Even though cultural factors are often referred to in the literature as one of the possible explanations for persisting differences in antibiotic consumption between countries, they are rarely defined and described. Furthermore, to our knowledge, there is no systematic literature review specifically describing cultural determinants of antibiotic use. The aim of this study was to identify and describe determinants of antibiotic use that are referred to in the literature as cultural, on a country-specific level in ambulatory care in Europe, and to better understand the influence of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in a primary care setting in order to direct future research.

Materials and method

Search strategy

A computer-based mixed research synthesis study of integrated design was chosen as relevant to the final assimilation of results from both qualitative and quantitative findings [14]. Two research teams, one in France and one in Norway, independently conducted a literature search according to the same predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The research strategy was devised with advice from an experienced librarian and included both medical and non-medical search engines: Pubmed, Cochrane Library, Science Direct, CAIRN, Erudit, Francis, http://www.openedition.org/, Wiley library online for the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, PsycNet and Social science citation index.

Key words identified with the MeSH thesaurus included “culture” (MeSH definition described in the introduction section), “antibiotics”/“antibacterial agents”/“antimicrobial agents”. The computer-based search was completed by backward snowballing from reference lists of eligible articles. Papers in both English and French were included.

Eligibility criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied: cross-cultural studies concerning antibiotic use in primary care in at least two European countries which included a description of cultural determinants, published between 1997 and 2015, studies based on primary study results. Research focusing only on countries outside Europe or on a single European country, involving neither primary care, antibiotic use, nor cultural determinants, published before 1997 or after 2015 and which were not based on primary study results was excluded.

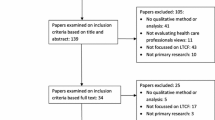

Study selection

The first exclusion was done manually after viewing the title or the abstract. Exclusion of eligible full text papers was based on exclusion criteria and quality assessment.

Study designs

Our literature review addressed both quantitative and qualitative studies. The study designs of the included quantitative studies were identified according to the algorithm suggested by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2012 [15] as correlation studies, and/or cross-sectional observational studies.

Quality assessment

The quality assessment strategy (QA) included selection and adaptation of QA tools according to the identified study design(s) and an independent quality assessment by 2 researchers, one in each research team. QA tools were selected taking into account recommendations from a recent systematic literature review by Sanderson et al. [16] in 2007 concerning quality assessing tools in observational studies. The authors advised simple checklists rather than scales, having shown evidence of validity and reliability, including a small number of key domains, and being as specific as possible with regard to study design and topic area to avoid bias in quality assessment. The simple checklists mentioned in this literature review that applied to cross-sectional studies were however specific to other topic areas such as mental health. Thus, the following tools were used according to the defined criteria [16]: the NICE recommendation tools for both the correlation and qualitative studies (score 2+: All or most of the checklist criteria have been fulfilled, where they have not been fulfilled, the conclusions are very unlikely to alter/ + / -); the Effective Public Health Practice project (EPHPP) QA tool for quantitative studies for the cross-sectional observational studies (score 1: strong / 2: moderate / 3: weak) was used [17]. However, minor adaptations were made for non-applicable sections. Any differences between the two researchers were discussed to reach consensus, the lower score was used if differences persisted.

Data extraction and description

Selected papers were then compiled and summarized using Zotero© software. To characterise each paper, the method, investigated countries, sampling and main results were extracted and tabulated in chronological order, initially according to their methodology, including the overall QA score.

Cultural determinants cited in both qualitative and quantitative selected papers were then extracted, categorized and tabulated including relevant references in a final unique table assimilating the results.

Finally, the influence of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions having shown an association with antibiotic consumption within the medical consultation in a primary care setting was identified and described.

Results

Article selection and characteristics of selected articles

Twenty-four eligible papers were identified, eight through free access search engines and 16 through backward snowballing from reference lists of eligible articles 11 of which were rejected according to exclusion criteria (six focused on a single country, two included countries outside Europe and three were not based on primary study results). In all, 13 papers that also met the QA assessment criteria (Additional file 1), taking into account their study design according to the applicable checklist scorings, were included in the literature review. The overall assessment score was two for cross-sectional studies with the adapted EPHPP tool and 2+ for correlation studies (internal and external validity) as well as for qualitative studies using the appropriate NICE checklists.

The characteristics of each selected paper were displayed in two separate tables according to their methodology: 11 studies used quantitative methods [12, 13, 18–26] (Additional file 2) and two studies used qualitative or mixed methods [27, 28] (Additional file 3).

Each study involved between two and 27 European countries, only one paper involved other international countries in addition to European ones. The Netherlands and Belgium were the most frequently studied. In quantitative studies, patient numbers ranged from 678 to 26 259.

Culture-related results

Within the quantitative papers, patients’ knowledge, attitudes, behaviour and education towards antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in the context of RTI were extensively explored [18–23, 25, 26] and were described as varying according to countries, in contrast to clinical outcomes. Different “patient types” were described in two studies [19, 20] according to treatment compliance and attitudes regarding antibiotics as well as respect or attitude towards the practitioner. These “patient types” were unequally distributed among countries. Geographical variation of appropriate attitudes according to location of the country in Europe (North versus South, East versus West) was observed in one study [23] which also found that awareness of antibiotic resistance was the main difference between the participating countries.

Only one paper focused on practitioners’ attitudes and beliefs [24] in 2 contrasting countries with regard to antibiotic use (France and the Netherlands), suggesting that cultural differences in patients’ health seeking behaviour and perception regarding medication could account, at least in part, for differences in antibiotic prescription patterns.

Two papers report a correlation between several of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and European data concerning antibiotic consumption, and also patients’ knowledge of antibiotics [12, 13]; these correlations were found between high antibiotic consumption and high scores of PD [12], UA [12, 13] and MF [12, 13] but did not persist when controlling for wealth.

One of the qualitative studies explored patients’ attitudes, knowledge and behaviour towards RTI and antibiotics [27] in two similar towns in two countries with contrasting antibiotic use (Belgium and the Netherlands). Major differences in disease labelling and initial coping behaviour were described in addition to attitudes towards antibiotics and expectations. The other qualitative study explored GPs’ antibiotic prescription patterns [28] in France and the Netherlands and described differences in prescription contexts in each country in particular with regards to initial medical training, legal complaints, retribution system and practice context.

Among the selected studies, 11 targeted adult patients and two targeted GPs.

Overview of categories of identified cultural determinants

The cited cultural determinants in each selected paper were extracted, categorized with regards to the consecutive stages of the disease process and described (Table 1) with relevant references. These determinants were patient-related (e.g. illness perception/behaviour and health-seeking behaviour, individual experience, drug perception, diagnostic label, work ethos, practitioner perception), practitioner-related (e.g. RTI management, initial training, legal complaints, practice context) or both (antibiotic awareness). Patients’ attitudes, beliefs and knowledge towards infections and antibiotics were the most frequently explored and identified cultural determinants.

Relation between identified cultural determinants and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in a primary care setting concerning antibiotics

The framework developed by Hofstede’s is the most frequently used in studies mentioning cultural influence on antibiotic use. According to several authors, the cultural dimensions of PD [12], UA [12, 13] and MF [12, 13] are correlated to antibiotic use. When these dimensions score highly, antibiotic prescription is seen as a sign of power and expertise (PD, Table 2), decreases GPs’ and patients’ fear linked to uncertainty of diagnosis and illness outcome (UA, Table 3) and is regarded as meeting the priority of continuing to work in spite of illness (MF, Table 4). The influence of these 3 cultural dimensions on the relationship and communication between the practitioner and the patient, which are closely linked to the decision to prescribe or not, is also reported (Tables 2–4). UA (Table 3) was the most frequently quoted cultural dimension from both the practitioners’ and the patients’ perspective.

Discussion

Main findings: “Culture is all around us”

The findings of this literature review allowed us to identify and categorize cultural determinants (Table 1) in different cultural primary care settings and to confront them with Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (Tables 2–4). The different determinants described as cultural in the selected papers concern the various stages of the disease process from the patient’s illness perception and health seeking behaviour up to the decision-making stage at the end of the consultation, suggesting an ubiquitous influence of culture. Several narrative literature reviews describe determinants of antibiotic consumption, identifying cultural determinants as one particular category among others, which are often described as linked to the practitioner, the patient, the health care system, the pathogen’s characteristics etc. [6, 29–32]. Thus, our literature review highlights the extensive influence of culture at different levels rather than being a category among other determinants. This is confirmed by Monnet’s and Harbarth’s conclusion that cultural and socioeconomic factors pervade all aspects of antibiotic use [6].

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge this is the first systematic review identifying and describing cultural determinants. The method we chose, i.e. to initially classify papers according to their methodology made it easier for us to identify future research in this field. The lack of exclusively qualitative studies was striking. Only two qualitative papers were identified, one involving patients and another involving GPs. Within the quantitative papers, patients’ knowledge, attitude and education concerning antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance were extensively investigated whereas GPs’ attitudes and beliefs were less explored although considered as important determinants of prescription particularly in high prescribing countries where there can be little patient involvement [27].

The research field of culture is complex, involving overlapping disciplines such as medicine, sociology, psychology, philosophy and anthropology making a systematic approach more difficult to undertake. Free accessibility of non-medical databases was limited. Defining a level of cultural comparison was necessary and our objective was to study country-specific culture. Relevant papers using other terms to designate cultural differences between countries may not have been identified. The representativeness of countries was unequal; some countries (France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany) were extensively described in the publications, whereas results from other countries were limited. A possible explanation could be the contrast in antibiotic consumption motivating the choice of these countries [4]. The heterogeneous methodology of the selected papers, including both quantitative and qualitative methods, complicated quality assessment as well as extraction, interpretation and presentation of the data. We therefore decided to initially separate the results according to the methodology of the selected papers.

Limitation of the study to European countries was motivated by the researchers’ nationality, and the numerous European interventions, papers and databases concerning antibiotic use and consumption as well as resistance rates. A wider international approach could have added other aspects to the study.

Publications targeting antibiotic self-medication were included because they provided valuable cultural information about antibiotic use.

Comparisons with published research

Influence of cultural dimensions on clinical practice

The findings of our literature review showed that UA (Table 3) was the most frequently quoted cultural dimension from both the practitioner’s and the patient’s perspective and proved to be significantly correlated with antibiotic consumption [12, 13]. Indeed, various authors highlight the challenge of diagnostic uncertainty faced by the practitioner or the illness outcome uncertainty motivating the patient to consult, even though the cultural perspective is not taken into account [32–35]. A French qualitative study [33] suggest that GPs use prescription to replace “uncertainty management” for which they have not been trained. The concept of uncertainty can also be considered from a wider perspective. Different attitudes towards risk-taking among GPs in different European countries were observed by Grol et al. [34], Dutch GPs had a lower level of “no risk-taking attitudes” than their colleagues in Belgium and the UK. Uncertainty was reported by many Belgian patients in Descheppers’ study [12] as a major motivation for rapidly seeking contact with a doctor and for requesting antibiotics. The authors describe differences in risk perception regarding disease among patients from different countries, including fear of complications of current infections and scepticism towards medicines. Gjelstad et al. [35] report results from the GRACE study concerning lower RTI, showing that the number of days that patients waited before consulting their GP varied from 3 to 12 between countries.

PD also influences the medical consultation (Table 2) one study showed a significant correlation with antibiotic consumption [12]. Different models of doctor-patient relationship are described in the literature and can easily be linked to levels of power distance. In a literature review, Butler et al. [36] describe the “paternalistic” doctor model, in which the physician knows what is best for the patient, the “patient’s choice” model after information given to the patient and the “consulting model” where information is exchanged between the doctor and the patient. Several national studies show the impact of communication between patient and practitioner on antibiotic prescribing, regardless of cultural aspects [37–40]. Meeuwesen et al. [41] investigated how cross-national differences in medical communication in 10 European countries can be understood through Hofstede’s cultural dimension framework. This observational study of consultations not specifically concerning antibiotics, showed that cultural norms, values, beliefs and attitudes towards health and health care may influence communication between doctors and their patients.

The third cultural dimension having proven significantly correlated to antibiotic use is MF [13] (Table 4) which is interesting to confront with patients’ differences in work ethos [27, 28] in different countries: giving priority to work in spite of illness in masculine societies or stopping work in order to allow recovery and decrease the risk of transmission of infection to others in feminine societies.

Interaction between education and culture

The very definition of culture is closely linked to learning and education. In our literature review, the most frequently quoted cultural determinant was patients’ attitudes, knowledge and beliefs towards infections and antibiotics (Table 1). Knowledge is a powerful determinant that can be influenced, considered either as a social factor, related to educational level [6], or as a cultural factor, depending on authors. Borg [13] suggests that knowledge can improve behaviour and thus decrease the cultural influence on antibiotic use. Radosevic et al. [26] found that all components of attitudes towards antibiotics were influenced by country and level of education. The 2009 Eurobarometer survey [42] suggests that persons with a higher level of knowledge take fewer antibiotics. Several information campaigns targeting the general public have been implemented in high-consuming countries such as France [43–45] and Belgium [46], contributing to increase knowledge among patients and reduce antibiotic consumption [47]. However, antibiotic consumption in both these countries remains among the highest in Europe, illustrating the challenge of educational campaigns. Another interesting European educational initiative concerning antibiotics is the e-Bug project [48] which has proved knowledge-efficient [49] initially targeting school children between 9 and 15 years of age in 18 European countries based on a country-specific needs assessment [50]. Cultural differences were taken into account when adapting and implementing it in each country [51–54]. However, educational level in general does not always exert a beneficial influence on antibiotic use. Grigoryan et al. [22] as well as McNulty et al. [55] found that one of the characteristics associated with antimicrobial self-medication was higher education.

Evolution of culture

Hofstede et al. [7] suggest that culture is a stable phenomenon exerting a very deep influence on each individual, describing a model of culture with different layers [10] (the onion diagram) where the core, represented by values, is the most difficult to change, compared to the more superficial layers or “practices”. This concept has been criticised by several authors. Classical authors, like Hegel, [56] suggest that culture undergoes continuous change. Herskovits [57] explains that culture is influenced by internal change resulting from technical or structural innovations within society (e.g. Telephone, television, internet, new laws…) and external change for example through immigration.

The World Values Surveys (WVS) [58] a global network of social scientists have conducted six surveys of values since 1981 in almost 100 countries (400 000 respondents in all) showing pervasive changes.In Blommaert et al’s [59] study identifying determinants of between-country differences in ambulatory antibiotic use and resistance in Europe, feelings of distrust and’feelings of religiousness (data from WVS) were the two determinants that could be considered as cultural and that were associated with total antibiotic use.

Implications for future research

The importance of studying culture in the context of antibiotic use has often been highlighted. Grigoryan et al. [22] advise that strategies and campaigns to improve the situation should take cultural determinants into account. Hulsher et al. [32] highlight that in order to be effective, any programme to promote appropriate antibiotic use should include cultural issues and stress the importance of close international collaboration to help overcoming wide differences between countries, often due to powerful cultural factors. The context of European projects is particularly relevant to study cultural influences. Raising cultural awareness could be useful to increase the chances of success of European projects concerning antibiotic use as well as on an individual level, helping the GP to better understand patients’ expectations during the medical consultation.

Even though Hofstede’s cultural dimensions are the most frequently studied in association with antibiotic prescription, many other frameworks have been described. Narrowing the cultural research field to Hofstede’s dimensions could prove misleading. It would be safer to consider a more extensive framework for further cultural research, such as those identified by Taras et al. who resorted to 121 different instruments to measure culture [60].

Conclusion

What was already known

It has been suggested that cultural factors may influence antibiotic use.

What this study added

This literature review identified various cultural determinants suggesting that cultural factors should not be considered as a separate category of determinants but as an ubiquitous influence on all the different stages of the disease process, from the first symptoms experienced by the patient to the decision by the practitioner to prescribe antibiotics or not, on the duration of illness and on treatment adherence by the patient. Interactions between categories of determinants, cultural dimensions and antibiotic use in primary care are multiple and complex and need further investigation which should include qualitative studies targeting both patients and GPs in order to deepen the understanding of the influence of cultural determinants on antibiotic use.

References

Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M. ESAC Project Group. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet. 2005;365(9459):579–87.

World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014. http://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/ Accessed 7 July 2015.

Huttner B, Goossens H, Verheij T, Harbarth S. Characteristics and outcomes of public campaigns aimed at improving the use of antibiotics in outpatients in high-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(1):17–31.

Adriaenssens N, Coenen S, Versporten A, Muller A, Minalu G, Faes C, et al. ESAC Project Group. European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC): outpatient antibiotic use in Europe (1997–2009). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(6):vi3–12.

Gagliotti C, Balode A, Baquero F, Degener J, Grundmann H, Gür D, et al. EARS-Net Participants (Disease Specific Contact Points for AMR). Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus: bad news and good news from the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net, formerly EARSS), 2002 to 2009. Euro Surveill. 2011;17:16(11).

Harbarth S, Monnet DL. Cultural and socioeconomic determinants of antibiotic use. In: Gould IM & van der Meer JWM (eds.). Antibiotic Policies: Fighting Resistance. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2007, pp. 29-40.

Hofstede G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. 2nd ed. London, UK, SAGE, 2001.

Trompenaars F, Hampden-Turner C, Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business, 2nd ed. New York, USA, McGraw-Hill, 1997.

Schwartz SH. Identifying Culture-Specifics in the Content and Structure of Values. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 1995;26(1):92–116.

Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ. Cultures and organizations, Software of the mind. 2nd ed. New York, USA, Mc Graw Hill 2005.

The Hofstede centre. http://geerthofstede.nl/dimensions-of-national-cultures Accessed 7 July 2015.

Deschepper R, Grigoryan L, Stålsby Lundborg C, Hofstede G, Cohen J, Van Der Kelen G, et al. Are cultural dimensions relevant for explaining cross-national differences in antibiotic use in Europe? BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:123.

Borg M. National cultural dimensions as drivers of inappropriate ambulatory care consumption of antibiotics in Europe and their relevance to awareness campaigns. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(3):763–7.

Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Barroso J. Defining and Designing Mixed Research Synthesis Studies. Res Sch. 2006;13(1):29.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance (second edition) 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/proxy/?sourceUrl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.nice.org.uk%2Fmedia%2FCE1%2FF7%2FCPHE_Methods_manual_LR.pdf Accessed 7 July 2015.

Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JP. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(3):666–76.

Effective Public Health Practice Project 2009. http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html. Accessed 7 July 2015.

de Melker RA, Touw-Otten FW, Kuyvenhoven MM. Transcultural differences in illness behaviour and clinical outcome: an underestimated aspect of general practice? Fam Pract. 1997;14(6):472–7.

Pechère JC. Patients’ interviews and misuse of antibiotics. Clinical Infectious Diseases. An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2001;33 Suppl 3:S170–3.

Pechère JC, Cenedese C, Müller O, Perez-Gorricho B, Ripoll M, Rossi A, et al. Attitudinal classification of patients receiving antibiotic treatment for mild respiratory tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;20(6):399–406.

van Duijn H, Kuyvenhoven M, Jones RT, Butler C, Coenen S, Van Royen P. Patients’ views on respiratory tract symptoms and antibiotics. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(491):491–2.

Grigoryan L, Haaijer-Ruskamp F, Burgerhof J, Mechtler R, Deschepper R, Tambic-Andrasevic A, et al. Self-medication with antimicrobial drugs in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(3):452–9.

Grigoryan L, Burgerho J, Degener J, Deschepper R, Stålsby Lundborg C, Monnet D, et al. Attitudes, beliefs and knowledge concerning antibiotic use and self-medication: a comparative European study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(11):1234–43.

Rosman S, Le Vaillant M, Schellevis F, Clerc P, Verheij R, Pelletier-Fleury N. Prescribing patterns for upper respiratory tract infections in general practice in France and in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(3):312–6.

Grigoryan L, Burgerhof J, Degener J, Deschepper R, Stålsby Lundborg C, Monnet D, et al. Determinants of self-medication with antibiotics in Europe: the impact of beliefs, country wealth and the healthcare system. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61(5):1172–9.

Radosević N, Vlahović-Palcevski V, Benko R, Peklar J, Miskulin I, Matuz M, et al. Attitudes towards antimicrobial drugs among general population in Croatia, Fyrom, Greece, Hungary. Serbia and Slovenia Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(8):691–6.

Deschepper R, Van der Stichele R, Haaijer-Ruskamp F. Cross-cultural differences in lay attitudes and utilisation of antibiotics in a Belgian and a Dutch city. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(2):161–9.

Rosman S. Les pratiques de prescription des antibiotiques en médicine générale en France et aux Pays-Bas. Médicaments et société: entre automédication et dépendence. Sociologie Santé. 2009;30:81–90.

Harbarth S, Albrich W, Goldmann DA, Huebner J. Control of multiply resistant cocci: do international comparisons help? Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1(4):251–61.

Harbarth S, Albrich W, Brun-Buisson C. Outpatient antibiotic use and prevalence of antibiotic-resistant pneumococci in France and Germany: a sociocultural perspective. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(12):1460–7.

Feron JM, Legrand D, Pestiaux D, Tulkens P. Antibiotic use in general practice in Belgium and France: between collective factors and individual responsibility. Pathol Biol. 2009;57(1):61–4.

Hulsher ME, Van der Meer JW, Grol RP. Antibiotic use: how to improve it? Int JMed Microbiol. 2010;300(6):351–6.

Anne Vega. Positivisme et dépendance : les usages socioculturels du médicament chez les médecins généralistes français. Sciences sociales et santé. 2012 (Vol. 30) 10.3917/sss.303.0071.

Grol R, Whitfield M, De Maeseneer J, Mokkink H. Attitudes to risk taking in medical decision making among British, Dutch and Belgian general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40(333):134–6.

Gjelstad S, Lindbaek M. Prognosis of respiratory tract infections in primary care, Accurate information can help reduce antibiotic prescribing. BMJ. 2013;347:f7185.

Butler CC, Kinnersley P, Prout H, Rollnick S, Edwards A, Elwyn G. Antibiotics and shared decision-making in primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48(3):435–40.

Butler CC, Rollnick S, Pill R, Maggs-Rapport F, Stott N. Understanding the culture of prescribing: qualitative study of general practitioners’ and patients’ perceptions of antibiotics for sore throats. BMJ. 1998;317(7159):637–42.

Altiner A, Brockmann S, Sielk M, Wilm S, Wegscheider K, Abholz HH. Reducing antibiotic prescriptions for acute cough by motivating GPs to change their attitudes to communication and empowering patients: a cluster-randomized intervention study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60(3):638–44.

Lundkvist J, Akerlind I, Borgquist L, Mölstad S. The more time spent on listening, the less time spent on prescribing antibiotics in general practice. Fam Pract. 2002;19(6):638–40.

Gjelstad S, Straand J, Dalen I, Fetveit A, Strøm H, Lindbæk M. Do general practitioners’ consultation rates influence their prescribing patterns of antibiotics for acute respiratory tract infections? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(10):2425–33.

Meeuwesen L, Van den Brink-Muinen A, Hofstede G. Can dimensions of national culture predict cross-national differences in medical communication ? Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75(1):58–66.

European commission. Special Eurobarometer 338; Antimicrobial resistance. April 2010 http://ec.europa.eu/health/antimicrobial_resistance/docs/ebs_338_en.pdf Accessed 7 July 2015.

Pradier C, Dunais B, Ricort-Patuano C, Maurin S, Andreini A, Hofliger P, et al. Campagne «Antibios quand il faut» mise en place dans le département des Alpes-Maritimes. Méd mal infect. 2003;33(1):9–14.

Sabuncu E, David J, Bernède-Bauduin C, Pépin S, Leroy M, Boëlle PY, et al. Significant reduction of antibiotic use in the community after a nationwide campaign in France, 2002–2007. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6), e1000084.

Chahwakilian P, Huttner B, Schlemmer B, Harbarth S. Impact of the French campaign to reduce inappropriate ambulatory antibiotic use on the prescription and consultation rates for respiratory tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(12):2872–9.

Goossens H, Guillemot D, Ferech M, Schlemmer B, Costers M, Van Breda M, et al. National campaigns to improve antibiotic use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62(5):373–9.

Huttner B, Harbarth S. “Antibiotics Are Not Automatic Anymore”—The French National Campaign To Cut Antibiotic Overuse. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6), e1000080.

Lecky DM, McNulty CA, Adriaenssens N, Koprivová Herotová T, Holt J, Kostkova P, et al. e-Bug Working Group. Development of an educational resource on microbes, hygiene and prudent antibiotic use for junior and senior school children. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(5):v23–31.

Lecky DM, McNulty CA, Touboul P, Herotova TK, Benes J, Dellamonica P, et al. e-Bug Working Group. Evaluation of e-Bug, an educational pack, teaching about prudent antibiotic use and hygiene, in the Czech Republic, France and England. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(12):2674–84.

Lecky DM, McNulty CA, Adriaenssens N, Koprivová Herotová T, Holt J, Touboul P, et al. e-Bug Working Group. What are school children in Europe being taught about hygiene and antibiotic use? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(5):v13–21.

Lecky DM, McNulty CA. e-Bug implementation in England. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(5):v63–6.

Touboul P, Dunais B, Urcun JM, Michard JL, Loarer C, Azanowsky JM, et al. The e-Bug project in France. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66 Suppl 5:v67–70.

Adriaenssens N, De Corte S, Coenen S, Grieten E, Goossens H. Implementation of e-Bug in Belgium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(5):v51–3.

Gennimata D, Merakou K, Barbouni A, Kremastinou J. Implementation of the e-Bug Project in Greece. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66 Suppl 5:v71–3.

McNulty C, Boyle P,Nichols T, Clappison P, Davey P. Don’t wear me out-the public’s knowledge of and attitudes to antibiotic use. J Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;59.

Hegel G. Lectures on the Philosophy of History. Bonn: Henry G; 1861.

Herskovits M J. Les Bases de l'anthropologie culturelle. Petite bibliothèque Payot, Paris, 1967.

The World Values Survey: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp Accessed 7 July 2015.

Blommaert A, Marais C, Hens N, Coenen S, Muller A, Goossens H, et al. Determinants of between-country differences in ambulatory antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in Europe: a longitudinal observational study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(2):535–4.

Taras V, Rowney J, Steel P. Half a century of measuring culture: Review of approaches, challenges, and limitations based on the analysis of 121 instruments for quantifying culture. J Int Manag. 2009;15(4):357–73.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Brigitte Dunais for the language revision.

Funding

None

Ethical approval

Not required

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PTL, SJ, JD, ML conceived the method and conducted the literature review. PTL drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Flow chart Literature review research strategy and results July 2015. (TIF 26 kb)

Additional file 2:

Characteristics of selected articles using quantitative methods. (PDF 35 kb)

Additional file 3:

Characteristics of selected articles using qualitative or mixed methods. (PDF 23 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Touboul-Lundgren, P., Jensen, S., Drai, J. et al. Identification of cultural determinants of antibiotic use cited in primary care in Europe: a mixed research synthesis study of integrated design “Culture is all around us”. BMC Public Health 15, 908 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2254-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2254-8