Abstract

Background

Harmful practices in the management of childhood diarrhea are associated with negative health outcomes, and conflict with WHO treatment guidelines. These practices include restriction of fluids, breast milk and/or food intake during diarrhea episodes, and incorrect use of modern medicines. We conducted a systematic review of English-language literature published since 1990 to assess the documented prevalence of these four harmful practices, and beliefs, motivations, and contextual factors associated with harmful practices in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods

We electronically searched PubMed, Embase, Ovid Global Health, and the WHO Global Health Library. Publications reporting the prevalence or substantive findings on beliefs, motivations, or context related to at least one of the four harmful practices were included, regardless of study design or representativeness of the sample population.

Results

Of the 114 articles included in the review, 79 reported the prevalence of at least one harmful practice and 35 studies reported on beliefs, motivations, or context for harmful practices. Most studies relied on sub-national population samples and many were limited to small sample sizes. Study design, study population, and definition of harmful practices varied across studies. Reported prevalence of harmful practices varied greatly across study populations, and we were unable to identify clearly defined patterns across regions, countries, or time periods. Caregivers reported that diarrhea management practices were based on the advice of others (health workers, relatives, community members), as well as their own observations or understanding of the efficacy of certain treatments for diarrhea. Others reported following traditionally held beliefs on the causes and cures for specific diarrheal diseases.

Conclusions

Available evidence suggests that harmful practices in diarrhea treatment are common in some countries with a high burden of diarrhea-related mortality. These practices can reduce correct management of diarrheal disease in children and result in treatment failure, sustained nutritional deficits, and increased diarrhea mortality. The lack of consistency in sampling, measurement, and reporting identified in this literature review highlights the need to document harmful practices using standard methods of measurement and reporting for the continued reduction of diarrhea mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diarrheal disease is a leading cause of mortality in children under five, resulting in around 750,000 deaths each year [1]. The WHO recommends first line management of diarrhea in children under five with continued feeding, increased fluids, and supplemental zinc for 10–14 days to prevent dehydration. In addition, the WHO guidelines state that children exhibiting non-severe dehydration should “receive oral rehydration therapy (ORT) with ORS solution in a health facility”. Antimicrobials are recommended only for the treatment of bloody diarrhea or suspected cholera with severe dehydration [2]. The full guidelines, which have evolved over time, are available at http://www.who.int/entity/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9241593180/en/index.html.

For decades, health initiatives have targeted the expansion of ORS and ORT, including the UNICEF Growth Monitoring, Oral Rehydration, Breastfeeding and Immunization (GOBI) initiative, the USAID/CDC Africa Child Survival Initiative - Combatting Childhood Communicable Diseases (ACSI-CCCD), and the WHO Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) initiative. Despite these efforts, a shift in global attention away from diarrhea management seems likely to have contributed to slowing – and even reversals – in progress toward full coverage for ORT [3, 4].

Many fewer programs have specifically targeted non-adherence to other recommended diarrhea management practices, such as the restriction of fluids, breast milk and/or food intake during diarrhea episodes, and incorrect use of modern medicines. All four of these practices are associated with negative outcomes and conflict with WHO treatment guidelines. Curtailment of fluids and restriction of feeding during diarrhea can increase the risk of dehydration, reduce nutritional intake, and potentially inhibit child growth and development. The use of antibiotics and other medications is appropriate only in the treatment of cholera or dysenteric diarrhea in children. Antidiarrheal drugs and some antiemetics not only have no benefit in diarrhea treatment, but may also cause serious, even life-threatening side effects in children [2]. We have referred to these as “harmful practices” from this point forward, understanding that under some circumstances these practices may not be detrimental.

This review summarizes existing literature on harmful practices in diarrhea case management in children under five years of age, including fluid and breastfeeding curtailment, food restriction, and inappropriate use of medications for diarrhea management in children in low- and middle-income countries. The primary objectives of the review are to:

-

Determine the documented prevalence of these four harmful practices across low- and middle-income populations, as reported in various studies since 1990;

-

Describe how these practices have been examined and reported on previously;

-

Explore beliefs, motivations, and contextual factors associated with harmful practices as reported through both quantitative and qualitative studies; and

-

Highlight associations between these harmful practices and other characteristics of the episode, child, caregiver, and household.

Findings from this review will identify critical next steps to address harmful practices in diarrhea management and ultimately improve child survival.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Ovid Global Health, and the WHO Global Health Library in September 2013. Papers were identified that included variations on the combination of the following terms within the publication’s title or abstract or as a keyword: 1) diarrhea; 2) low- and middle-income country; and one or more terms related to 3) a harmful practice or general management of diarrhea. Search terms were developed in PubMed (see Additional file 1) and translated for the three other databases. Publications were restricted to English-language articles published after 1990.

Quantitative articles were included if the paper reported the prevalence of at least one of the four harmful practices associated with caregiver management of diarrhea in children under the age of five, regardless of study design or representativeness of the sample population. Qualitative articles, or quantitative articles not meeting the quantitative inclusion criteria, were included if they presented substantive findings on beliefs, motivations, or context related to at least one of the four practices in caregiver management of childhood diarrhea. Publications were excluded if they exclusively reported data collected prior to 1990, exclusively reported provider practices, reported findings post-intervention only, or did not specifically focus on treatment of children under 5 years of age. Due to the variety of study designs included in the review, study quality was not formally assessed, because multiple quality assessment frameworks would have been required.

Data extraction was completed by the first author (EC). For all studies, information on the study design, study population, and sample size was extracted. For studies reporting prevalence of practices, data were extracted on the definition of the practice measure, the reported prevalence of the practice, and variation in the practice by other factors (reported as stratified prevalence or odds ratio). For non-prevalence studies, data were extracted related to beliefs, motivations, or context directly related to one or more of the harmful practices and then classified by common themes.

We summarize the results for each of the four harmful practices in the results section of the manuscript. For each practice, we: (1) describe how the practice was defined and measured in these studies; (2) summarize reported findings on prevalence, including variations by characteristics of the diarrhea episode, child, caregiver, and household; and (3) report on beliefs, motivations, and contextual factors investigated and relevant results.

Results

The initial search yielded 2,266 articles in Pubmed, 2,512 articles in Embase, 1,512 articles in Ovid Global Health, and 1,890 articles in the WHO Global Health Library. After removing duplicates, 4,270 unique articles remained. Title and abstract review and full article review were conducted by the first author (EC). After reviewing titles and abstracts, 294 articles were identified for full article review. Based on a review of the full article, 157 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria and a full text copy of 23 manuscripts could not be located. In total, 114 publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (Fig. 1). Of the 79 studies reporting the prevalence of at least one harmful practice, 54 studies utilized a population-based cross-sectional sample (3 nationally representative), 12 studies used a non-cross-sectional design but included a representative population sample, and 13 studies employed a non-representative sample. Of the 35 studies reporting on beliefs, motivations, or context for harmful practices, 9 studies used exclusively qualitative methods, 8 studies used mixed-methods, and 18 studies used exclusively quantitative methods (12 with a representative sample, 6 with a non-representative sample). Although there have been summaries of relevant Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) findings [5, 6], we were unable to identify any country-specific secondary analyses on this topic.

Study characteristics

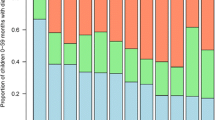

The publication dates of the 114 studies included in the review were relatively evenly distributed over the period from 1990 to 2013, with publications clustering slightly in the early 1990s and late 2000s/early 2010s. The majority of studies were conducted in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 2). The number of publications reporting on the prevalence of each of the four practices varied, with the highest proportion reporting on inappropriate medication use (70 %), followed in order of frequency by food restriction (56 %), curtailment of fluids other than breast milk (53 %), and breastfeeding restriction (37 %).

Respondents in the majority of prevalence studies were caregivers of children under 5 years of age, although some studies interviewed mothers exclusively. The age of children referenced for the practice also varied, with the majority of studies referencing children under 5 years of age. The definition of the diarrhea reference episode also varied, ranging from diarrhea in the past 24 h to the most recent diarrhea event, although the most common reference period was the previous two weeks.

Fluid curtailment

The measurement of fluid intake, and prevalence estimates, varied widely across studies (Table 1, Column 4). Many studies differed in their definition or failed to specify if fluid restriction included or excluded breastfeeding or assessed amount of fluid offered versus consumed. The reported practice of curtailing fluids during a recent episode of diarrhea ranged from as low as 11 % of caregivers in Mirzapur, Bangladesh [7] to over 80 % of caregivers in Kenya’s Nyanza province [8]. Where specified by the study authors, the practice of stopping all fluids was uncommon, generally reported in fewer than 10 % of episodes.

Multiple studies explored variations in fluid curtailment by characteristics of the diarrhea episode, child, caregiver, and household (Table 2). Fluid curtailment was associated with diarrhea severity and vomiting in two studies [9, 10], whereas increase in fluid was associated with long illness duration and poor appetite [11]. Studies in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Saudi Arabia found no clear association between fluid restriction and the age of the child [12–14]. However, a study in Mozambique reported that less fluid was given to infants relative to older children [15]. Younger mothers and mothers who did not work outside the home [12] and less educated mothers [16] were more likely to curtail fluids.

Multiple studies have attributed the practice of fluid curtailment to caregiver beliefs about the impact of fluid intake on a child’s diarrhea episode (Table 3). Multiple studies reported that caregivers often stated that more or specific fluids would increase the severity of the illness [17–19] or could not be digested [20–22]. Two studies suggested these beliefs were informed by caregivers’ observations that reduced fluids decreased stool output and diarrhea intensity [7, 23]. One study reported that certain types of diarrhea are perceived to be manageable by adjusting fluid intake, while others require traditional or spiritual methods, or no treatment at all [24]. The beliefs of family and community members, particularly elderly relatives, have also been reported as influential in determining caregiver practices related to fluids and feeding during childhood diarrhea episodes [22, 24, 25]. In three studies caregivers reported reduced fluid intake due to child refusal, child crying, or decreased thirst [22, 26, 27]. In one study, mothers reported they did not encourage increased fluids because they were inexperienced in how to do this [27].

Breastfeeding reduction

Many studies reported the practice of breastfeeding reduction or cessation during diarrhea episodes (Table 1, Column 5). Most studies found that among mothers breastfeeding their child prior to the onset of diarrhea, fewer than 10 % of mothers stopped breastfeeding during the episode. The practice of breastfeeding cessation ranged from no mothers reporting breastfeeding cessation in a surveillance study in northeast Thailand to 62 % of mothers reporting stopping breast or milk feeding in a hospital-based study in Saudi Arabia [20, 28]. The practice of breastfeeding cessation was higher in hospital samples compared to samples from the general population. Where breastfeeding reduction was reported, on average one quarter of mothers reported reducing breastfeeding, although there was significant variation in the practice.

Multiple studies assessed variance in breastfeeding restriction by factors including characteristics of the diarrhea episode, child, caregiver, and household (Table 2). One study found younger and less educated mothers were more likely to reduce breastfeeding during episodes of diarrhea [12].

Mothers reported ceasing or reducing breastfeeding when their child had diarrhea for various reasons (Table 3). Mothers reported stopping or reducing breastfeeding because of beliefs that breastmilk was too fatty to be digested [20]. Others reported continued breastfeeding would not reduce the duration of diarrhea [20, 29] or could cause or worsen the diarrhea [18, 19, 29]. Caregivers in two studies believed specific types of diarrhea must be treated with breastfeeding cessation [29, 30]. In multiple cultures, “dirty” breast milk or secretion of ingested food through breast milk was thought to cause certain types of diarrhea. Mothers received treatment or a modified diet to improve the quality of their breast milk [31–34] or children were weaned [35]. Some caregivers stated they were following the advice of healthcare providers by restricting breastfeeding [20, 36]. Older relatives were also important sources of information on feeding practices during diarrhea episodes [25, 31]. In some studies, mothers continued feeding but diluted milk or formula [29], switched to powdered or goat’s milk [37], or only gave water [38].

Food restriction

The measurement of food restriction, and prevalence estimates, varied widely across studies (Table 1, Column 6). Many studies differed in their definition or failed to specify if food restriction was measured only among those eating solid foods prior to illness, whether breastfeeding was included or excluded, and whether amount of food offered versus consumed was measured. Findings on restriction of specific foods have been included for context but not in prevalence estimates of overall food restriction (Table 1). The practice of stopping all food ranged from as low as 3 % of mothers stating they stopped giving solid or semi-solid foods during the episode in Oyo State, Nigeria [26] to as high as 53 % of mothers reporting they stopped feeding in Kenya [39]. As expected, measures that included the reduction of feeding in addition to complete restriction of feeding showed higher rates of food restriction, mostly within the range of 30–60 % of episodes.

Multiple studies addressed the variance of food restriction by other factors, including characteristics of the diarrhea episode, child, caregiver, and household (Table 2). Food curtailment was associated with dehydration and more severe disease [40], seeking care outside of the home, and ORS use [41]. In one study, caregivers were more likely to withhold food if a child had fever or a low appetite [11]. Another study found children less than 2 years of age were more likely to receive continued feeding compared to older children [42]. Two studies found that less educated mothers were more likely to restrict foods [12, 16].

Motivation for food restriction differed (Table 3). Some caregivers reported that a child’s diet should be restricted because of beliefs that a child cannot eat or digest as much during a diarrhea episode [22, 43] and feeding can exacerbate or prolong diarrhea episodes [19, 22, 29, 44–46]. Belief that only certain foods should be restricted because they can aggravate diarrhea was common across countries and included a range of foods such as meat, milk, sweet food, greasy food, high carbohydrate and high protein foods [29, 37, 38, 43, 47–54]. Alternatively, in two studies some caregivers reported that specific foods were customary and should be given during a diarrhea episode to strengthen the bowel or soothe the stomach [36, 52]. Some caregivers reported that restriction of certain foods was based on long held folk tradition [29, 47]. Others reported that diet alteration is based on the type or perceived cause of the diarrhea [18, 29, 55]. Elderly relatives, neighbors, and health care providers were reported to influence mothers’ feeding practices in many contexts [22, 23, 25, 27, 29, 36, 53, 56, 57]. Some caregivers reported that a child’s diet was not restricted during diarrhea because it was already limited [27, 44, 58]. One study reported mothers coaxed their child to eat more [36], but others reported some mothers of children with decreased appetite were unfamiliar with encouraging children to eat [22, 44] or had little time to prepare additional food because they were caring for the child [22]. One study suggested caregivers felt continued feeding was less important if they had been given some treatment at a health facility [31].

Inappropriate medication use

Many studies reported the use of drugs to treat diarrhea in children under five (Table 1, Column 7). The most commonly reported measures were the use of an antibiotic or antimicrobial, followed by use of any medicine, and the use of an antidiarrheal or antimotility agent. While antibiotics are recommended for treatment of dysentery or cholera, most studies did not differentiate between simple and dysenteric diarrhea when reporting on antibiotic use. The Lives Saved Tool (LiST) attributes 7 % of diarrhea cases in children under 5 to dysentery [59], therefor it may be inferred that high antibiotic use rates are inclusive of inappropriate antibiotic use. A hospital-based study in Enugu, Nigeria highlights the difficultly of collecting information on the type of medicine used to treat diarrhea. The study reported that 70 % of mothers misclassified antibiotics and analgesics as antimotility agents when self-reporting drugs used in diarrhea treatment [60]. Multiple studies outside of this review have shown that the accuracy of drug recall varies by questionnaire design and method of assessment [61].

Reported use of antidiarrheal and antimotility agents was generally lower than reported use of antibiotics. Use of antibiotics at any point in an episode ranged from 10-77 %. Antidiarrheal use ranged from 3–45 % of diarrhea episodes, with the exception of very high reported use (74 %) in Egypt in 2002 [62]. Use of any drug for a diarrhea episode occurring in the previous 2 weeks ranged from 26–76 %. Studies that used a shorter reference period limited to the previous 24 h reported lower rates of drug use at around 20 %.

Multiple studies addressed variance in inappropriate medication use by factors including characteristics of the diarrhea episode, child, caregiver, and household (Table 2). A hospital-based study in Nigeria found children who had received an antibacterial or antidiarrheal at home presented to the hospital with more severe dehydration than those children who did not receive these drugs [60]. Antibiotic and/or antidiarrheal use were associated with seeking care outside of the home [11, 41] and use of ORT [60, 63]. Two studies in Enugu, Nigeria reported conflicting associations between maternal education and antibiotic use [60, 64].

Caregivers reported using antibiotics and other drugs to treat diarrhea because they were accessible and believed to be efficacious (Table 3). Multiple studies reported caregiver beliefs that modern medicines are powerful [64–67], and more effective in treating diarrhea than ORS [65, 68]. Multiple studies reported drugs were widely available and affordable in the public and private sector, typically without prescription [35, 38, 40, 44, 49, 52, 64, 69]. In many contexts, caregivers stocked drugs at home, purchasing them in advance or saving leftover medication from previous illnesses [33, 37, 38, 52, 70]. Caregivers perceived drugs to be cheaper and more accessible than ORS, particularly given the flexibility to purchase a few tablets for little money [64, 65, 71]. Use of antibiotics in the treatment of pediatric diarrhea has become routine for both health care providers and caregivers in some contexts [18, 40, 66]. Caregivers may have also influenced provider behavior as caregivers’ preference for drug therapies creates pressure on providers to give medications in addition or instead of ORS [28, 33, 65, 72]. Drugs were given in sub-clinical doses in multiple studies [67, 69, 73]. It was common in studies for children to receive multiple drugs for a single episode of diarrhea, often from the same source [67, 74–77]. A study in Brazil found drugs were used more commonly to treat episodes of longer duration [63], although initial treatment of diarrhea at home with drugs was common in a study in Mali [78]. Multiple studies suggested treatment with modern medicines may be related to the perceived cause or type of diarrhea [18, 52, 60, 79–81]. Treatment seeking was often related to inappropriate use of medicine for diarrhea management [33, 57, 62, 82].

Discussion

This is the first review, to our knowledge, that addresses harmful practices related to fluids, feeding and medication use during episodes of childhood diarrhea. The findings indicate that there have been many studies – both quantitative and qualitative – that have documented these harmful practices. However, reported prevalence varies greatly across study populations, and we were unable to identify clearly defined patterns across regions, countries, or time periods. A limited number of studies looked at the variation of these harmful practices across potential influencing factors, including characteristics of the diarrhea episode and child, caregiver, or household-level traits. Findings of association differed across studies.

The motivation for harmful practices during diarrhea treatment also appears to vary across populations, although studies consistently report general caregiver concern for their child’s health and caregiver action to treat the illness to the best of their knowledge and abilities. Caregivers reported that their actions were based on the advice of health care providers, community members, or elderly relatives, as well as their own observations or understanding of the efficacy of certain treatments for diarrhea. Others reported following traditionally held beliefs on the causes and cures for specific diarrheal diseases.

Across studies, the measurement of harmful practices was inconsistent and not guided by a conceptual or theoretical framework. Most studies were focused on general practices in diarrhea treatment, and harmful practices were rarely a primary outcome of interest. This has limited the availability and quality of data on the topic. Variations in study design, sample populations, diarrhea episode reference periods, and measurement definitions make drawing comparisons and conclusions across studies challenging. This is further compounded by inconsistent quality in data collection and reporting. Most studies relied on sub-national population samples and many were limited to small sample sizes. The variation in treatment practices by perceived type of diarrhea highlights the importance of using local terminology in order to capture all episodes of diarrhea as perceived by the community [83]. Although the majority of studies included in this review used a recall period of diarrhea in the past two weeks, there was some variation ranging from the past 24 h to past six months or the “most recent” episode of diarrhea. Fischer-Walker and her colleagues highlight the importance of using a shorter recall period for capturing episodes of diarrhea of varying severity [83].

Although this systematic review highlighted limitations of existing research, the available evidence suggests that harmful practices in diarrhea treatment are common in certain populations. A multicountry analysis using MICS data from 28 countries between 2005–2007 reported the majority of mothers did not maintain their child’s nutritional intake during illness [5]. Analysis of DHS data from 14 countries between 1986–2003 suggests a decreasing trend in continued feeding in a majority of countries [6]. These practices can reduce correct management of diarrheal disease in children and result in treatment failure and sustained nutritional deficits. The lack of consistency in sampling, measurement, and reporting identified in this literature review highlights the need to document harmful practices using standard methods of measurement and reporting. Going forward, studies in this area would benefit from the development and use of a broader conceptual framework to ensure that the research is theory-driven and regularly synthesized. Multi-country analyses using MICS and DHS data have been conducted in the past, but they have tended to focus on positive treatment practices rather than harmful practices [5, 6]. Assessing harmful practices with nationally representative data and standardized measurements, through the analysis of the most recently available DHS and MICS data, can contribute to the discussion on improved care of diarrheal disease in children under five.

The strengths of this literature review include applying a systematic process for searching and summarizing the literature, and accessing articles during a time frame in which global efforts focused on improving coverage. This review was limited by the inclusion of only peer-reviewed literature and the exclusion of non-English language publications. Additionally, the quality of individual articles was not assessed, allowing for the potential inclusion of studies with misrepresentative findings.

Conclusions

Harmful practices in the management of childhood diarrhea are prevalent to varying degrees across cultures and include fluid and breastfeeding curtailment, food restriction, and inappropriate medication use. Inappropriate management of diarrhea episodes can result in higher risk of mortality through increased levels of dehydration or lasting health consequences as a result of nutritional restrictions or prolonged diarrhea illness. These practices must therefore be addressed as a matter of urgency in maternal, newborn and child health programs. These programs need to target not only the behaviors of child caregivers, but the broader social network, because our findings show that these practices are often informed by traditional beliefs, popular knowledge, and the instruction of authority figures, including elderly community members and health workers. Broader health systems interventions are also needed to address the alarming findings of high rates of inappropriate use of medications during diarrhea episodes. In addition, the global health community must do a better job or measuring the prevalence of these practices in standard ways, to produce evidence that can be used as the basis for action.

References

STATISTICS BY AREA/Child Survival and Health: Diarrhoea [http://www.childinfo.org/diarrhoea.html]

World Health Organization. The treatment of diarrhoea: a manual for physicians and other senior health workers. Geneva: WHO; 2005. p. 1–50.

Wardlaw T, Salama P, Brocklehurst C, Chopra M, Mason E. Diarrhoea: why children are still dying and what can be done. The Lancet. 2010;375(9718):870–2.

Wilson SE, Morris SS, Gilbert SS, Mosites E, Hackleman R, Weum KL, et al. Scaling up access to oral rehydration solution for diarrhea: Learning from historical experience in low–and high–performing countries. J Glob Health. 2013;3:1.

Arabi M, Frongillo EA, Avula R, Mangasaryan N. Infant and young child feeding in developing countries. Child Dev. 2012;83(1):32–45.

Forsberg BC, Petzold MG, Tomson G, Allebeck P. Diarrhoea case management in low- and middle-income countries--an unfinished agenda. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(1):42–8.

Othero DM, Orago AS, Groenewegen T, Kaseje DO, Otengah PA. Home management of diarrhea among underfives in a rural community in Kenya: household perceptions and practices. East Afr J Public Health. 2008;5(3):142–6.

Kaatano GM, Muro AI, Medard M. Caretaker’s perceptions, attitudes and practices regarding childhood febrile illness and diarrhoeal diseases among riparian communities of Lake Victoria, Tanzania. Tanzan Health Res Bull. 2006;8(3):155–61.

Mediratta RP, Feleke A, Moulton LH, Yifru S, Sack RB. Risk factors and case management of acute diarrhoea in North Gondar Zone, Ethiopia. J Health Popul Nutr. 2010;28(3):253–63.

Babaniyi OA, Maciak BJ, Wambai Z. Management of diarrhoea at the household level: a population-based survey in Suleja, Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 1994;71(8):531–5.

Wilson SE, Ouedraogo CT, Prince L, Ouedraogo A, Hess SY, Rouamba N, et al. Caregiver recognition of childhood diarrhea, care seeking behaviors and home treatment practices in rural Burkina Faso: a cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33273.

Bani IA, Saeed AA, Othman AA. Diarrhoea and child feeding practices in Saudi Arabia. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(6):727–31.

Quadri F, Nasrin D, Khan A, Bokhari T, Tikmani SS, Nisar MI, et al. Health care use patterns for diarrhea in children in low-income periurban communities of karachi, Pakistan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89(Suppl1):49–55.

Das SK, Nasrin D, Ahmed S, Wu Y, Ferdous F, Farzana FD, et al. Health care-seeking behavior for childhood diarrhea in mirzapur, Rural Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89(Suppl1):62–8.

Nhampossa T, Mandomando I, Acacio S, Nhalungo D, Sacoor C, Nhacolo A, et al. Health care utilization and attitudes survey in cases of moderate-to-severe diarrhea among children ages 0–59 months in the District of Manhica, southern Mozambique. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89(1 Suppl):41–8.

Berisha M, Hoxha-Gashi S, Gashi M, Ramadani N. Maternal practice on management of acute diarrhea among children under five years old in Kosova. Turk Silahl Kuvvetleri Koruyucu Hekimlik Bulteni. 2009;8(5):369–72.

Olango P, Aboud F. Determinants of mothers’ treatment of diarrhea in rural Ethiopia. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31(11):1245–9.

Pylypa J. Elder authority and the situational diagnosis of diarrheal disease as normal infant development in northeast Thailand. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(7):965–75.

Ikpatt NW, Young MU. Preliminary study on the attitude of people in two states of Nigeria on diarrhoeal disease and its management. East Afr Med J. 1992;69(4):219–22.

Moawed SA, Saeed AA. Knowledge and practices of mothers about infants’ diarrheal episodes. Saudi Med J. 2000;21(12):1147–51.

Bachrach LR, Gardner JM. Caregiver knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding childhood diarrhea and dehydration in Kingston. Jamaica Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2002;12(1):37–44.

Dearden KA, Quan LN, Do M, Marsh DR, Schroeder DG, Pachon H, et al. What influences health behavior? Learning from caregivers of young children in Viet Nam. Food Nutr Bull. 2002;23(4 SUPP):119–29.

Rasania SK, Gulati N, Sahgal K. Maternal beliefs regarding diet during acute diarrhea. Indian Pediatr. 1993;30(5):670–2.

Ansari M, Ibrahim MI, Hassali MA, Shankar PR, Koirala A, Thapa NJ. Mothers’ beliefs and barriers about childhood diarrhea and its management in Morang district, Nepal. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:576.

Chandrashekar S, Chakladar BK, Rao RS. Infant feeding--knowledge and attitudes in a rural area of Karnataka. Indian J Pediatr. 1995;62(6):707–12.

Okunribido OO, Brieger WR, Omotade OO, Adeyemo AA. Cultural perceptions of diarrhea and illness management choices among yoruba mothers in oyo state, Nigeria. Int Q Community Health Educ. 1997;17(3):309–18.

Ali M, Atkinson D, Underwood P. Determinants of use rate of oral rehydration therapy for management of childhood diarrhoea in rural Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2000;18(2):103–8.

Prohmmo A, Cook LA, Murdoch DR. Childhood diarrhoea in a district in northeast Thailand: incidence and treatment choices. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2006;18(2):26–32.

Ogunbiyi BO, Akinyele IO. Knowledge and belief of nursing mothers on nutritional management of acute diarrhoea in infants, Ibadan, Nigeria. (Special Issue: Diversity of research.). Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2010;10(3):2291–304.

Kaltenthaler EC, Drasar BS. Understanding of hygiene behaviour and diarrhoea in two villages in Botswana. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1996;14(2):75–80.

Shah MS, Ahmad A, Khalique N, Afzal S, Ansari MA, Khan Z. Home-based management of acute diarrhoeal disease in an urban slum of Aligarh, India. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6(2):137–42.

Kauchali S, Rollins N, Van den Broeck J. Local beliefs about childhood diarrhoea: importance for healthcare and research. J Trop Pediatr. 2004;50(2):82–9.

Vazquez ML, Mosquera M, Kroeger A. People’s concepts on diarrhea and dehydration in Nicaragua: the difficulty of the intercultural dialogue. Revista Brasileira de Saude Materno Infantil. 2002;2(3):223–37.

Nkwi PN. Perceptions and treatment of diarrhoeal diseases in Cameroon. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1994;12(1):35–41.

Munthali AC. Change and continuity in the management of diarrhoeal diseases in under-five children in rural Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2005;16(2):43–6.

Almroth S, Mohale M, Latham MC. Grandma ahead of her time: traditional ways of diarrhoea management in Lesotho. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1997;15(3):167–72.

Azim SM, Rahaman MM. Home management of childhood diarrhoea in rural Afghanistan: a study in Urgun, Paktika Province. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1993;11(3):161–4.

Omotade OO, Adeyemo AA, Kayode CM, Oladepo O. Treatment of childhood diarrhoea in Nigeria: need for adaptation of health policy and programmes to cultural norms. J Health Popul Nutr. 2000;18(3):139–44.

Oyoo A, Burstrom B, Forsberg B, Makhulo J. Rapid feedback from household surveys in PHC planning: An example from Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 1991;6(4):380–3.

Perez-Cuevas R, Guiscafre H, Romero G, Rodriguez L, Gutierrez G. Mothers’ health-seeking behaviour in acute diarrhoea in Tlaxcala, Mexico. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1996;14(4):260–8.

Omore R, O'Reilly CE, Williamson J, Moke F, Were V, Farag TH, et al. Health care-seeking behavior during childhood diarrheal illness: results of health care utilization and attitudes surveys of caretakers in western Kenya, 2007–2010. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89(1 Suppl):29–40.

Olson CK, Blum LS, Patel KN, Oria PA, Feikin DR, Laserson KF, et al. Community case management of childhood diarrhea in a setting with declining use of oral rehydration therapy: findings from cross-sectional studies among primary household caregivers, Kenya, 2007. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85(6):1134–40.

Singh MB. Maternal beliefs and practices regarding the diet and use of herbal medicines during measles and diarrhea in rural areas. Indian Pediatr. 1994;31(3):340–3.

Hudelson P, Aguilar E, Charaly MD, Marca D, Herrera M. Improving the home management of childhood diarrhoea in Bolivia. Int Q Community Health Educ. 1994;15(1):91–104.

Uchendu UO, Emodi IJ, Ikefuna AN. Pre-hospital management of diarrhoea among caregivers presenting at a tertiary health institution: implications for practice and health education. Afr Health Sci. 2011;11(1):41–7.

Ahmed F, Farheen A, Ali I, Thakur M, Muzaffar A, Samina M. Management of diarrhea in under-fives at home and health facilities in Kashmir. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2009;3(2):171–5.

Ekanem EE, Akitoye CO. Child feeding by Nigerian mothers during acute diarrhoeal illness. J R Soc Health. 1990;110(5):164–5.

Jinadu MK, Odebiyi O, Fayewonyom BA. Feeding practices of mothers during childhood diarrhoea in a rural area of Nigeria. Trop Med Int Health. 1996;1(5):684–9.

McLennan JD. Home management of childhood diarrhoea in a poor periurban community in Dominican Republic. J Health Popul Nutr. 2002;20(3):245–54.

Ali NS, Azam SI, Noor R. Women’s beliefs regarding food restrictions during common childhood illnesses: a hospital based study. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2003;15(1):26–8.

Smith GD, Gorter A, Hoppenbrouwer J, Sweep A, Perez RM, Gonzalez C, et al. The cultural construction of childhood diarrhoea in rural Nicaragua: relevance for epidemiology and health promotion. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(12):1613–24.

Martinez H, Saucedo G. Mothers’ perceptions about childhood diarrhoea in rural Mexico. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1991;9(3):235–43.

Amini-Ranjbar S, Bavafa B. Iranian mother’s child feeding practices during diarrhea: A study in Kerman. Pakistan J Nutr. 2007;6(3):217–9.

Bhatia V, Swami HM, Bhatia M, Bhatia SP. Attitude and practices regarding diarrhoea in rural community in Chandigarh. Indian J Pediatr. 1999;66(4):499–503.

Mushtaque A, Chowdhury R, Kabir ZN. Folk terminology for diarrhea in rural Bangladesh. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(Suppl 4):S252–254.

Olakunle JM, Valentine UO, Kamaldeen AS, Buhari ASM. Assessment of mothers’ knowledge of home management of childhood diarrhea in a Nigerian setting. Int J Pharmaceut Res Bio Sci. 2012;1(4):168–84.

Langsten R, Hill K. Treatment of childhood diarrhea in rural Egypt. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(7):989–1001.

Baclig PV, Patrick WK. The cultural definition of an infantile diarrhea in Tambon Korat and Koongyang, northeast Thailand: community perceptions in diarrhea control. Asia Pac J Public Health. 1990;4(1):59–64.

Walker CLF, Walker N. The Lives Saved Tool (LiST) as a model for diarrhea mortality reduction. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):70.

Uchendu UO, Ikefuna AN, Emodi IJ. Medication use and abuse in childhood diarrhoeal diseases by caregivers reporting to a Nigerian tertiary health institution. South Afr J Child Health. 2009;3(3):83–9.

Gama H, Correia S, Lunet N. Questionnaire design and the recall of pharmacological treatments: a systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(3):175–87.

El-Gilany AH, Hammad S. Epidemiology of diarrhoeal diseases among children under age 5 years in Dakahlia, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11(4):762–75.

Strina A, Cairncross S, Prado MS, Teles CA, Barreto ML. Childhood diarrhoea symptoms, management and duration: observations from a longitudinal community study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99(6):407–16.

Ekwochi U, Chinawa JM, Obi I, Obu HA, Agwu S. Use and/or misuse of antibiotics in management of diarrhea among children in Enugu, Southeast Nigeria. J Trop Pediatr. 2013;59(4):314–6.

Wongsaroj T, Thavornnunth J, Charanasri U. Study on the management of diarrhea in young children at community level in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 1997;80(3):178–82.

Hoa NQ, Ohman A, Lundborg CS, Chuc NTK. Drug use and health-seeking behavior for childhood illness in Vietnam-A qualitative study. Health Policy. 2007;82(3):320–9.

Rheinlander T, Samuelsen H, Dalsgaard A, Konradsen F. Perspectives on child diarrhoea management and health service use among ethnic minority caregivers in Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:690.

Zwisler G, Simpson E, Moodley M. Treatment of diarrhea in young children: results from surveys on the perception and use of oral rehydration solutions, antibiotics, and other therapies in India and Kenya. J Glob Health. 2013;3(1):10403.

Le TH, Ottosson E, Nguyen TK, Kim BG, Allebeck P. Drug use and self-medication among children with respiratory illness or diarrhea in a rural district in Vietnam: a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;4:329–36.

Okumura J, Wakai S, Umenai T. Drug utilisation and self-medication in rural communities in Vietnam. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(12):1875–86.

Winch PJ, Gilroy KE, Doumbia S, Patterson AE, Daou Z, Diawara A, et al. Operational issues and trends associated with the pilot introduction of zinc for childhood diarrhoea in Bougouni district, Mali. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26(2):151–62.

Friend-du Preez N, Cameron N, Griffiths P. “So they believe that if the baby is sick you must give drugs…” The importance of medicines in health-seeking behaviour for childhood illnesses in urban South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2013;92:43–52.

Baqui AH, Black RE, El Arifeen S, Yunus M, Zaman K, Begum N, et al. Zinc therapy for diarrhoea increased the use of oral rehydration therapy and reduced the use of antibiotics in Bangladeshi children. J Health Popul Nutr. 2004;22(4):440–2.

Okoro BA, Jones IO. Pattern of drug therapy in home management of diarrhoea in rural communities of Nigeria. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1995;13(3):151–4.

Jousilahti P, Madkour SM, Lambrechts T, Sherwin E. Diarrhoeal disease morbidity and home treatment practices in Egypt. Public Health. 1997;111(1):5–10.

World Health Organization. Diarrhoeal diseases household case management survey, Nepal, June, 1990 (Extended WER). Geneva: WHO; 1991. p. 22.

Diarrhoeal disease control (CDD) and acute respiratory infections (ARI). Combined CDD/ARI/breast-feeding survey, 1992. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 1993;68(17):120–122.

Ellis AA, Winch P, Daou Z, Gilroy KE, Swedberg E. Home management of childhood diarrhoea in southern Mali--implications for the introduction of zinc treatment. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(3):701–12.

Gorter AC, Sanchez G, Pauw J, Perez RM, Sandiford P, Smith GD. Childhood diarrhoea in rural Nicaragua: beliefs and traditional health practices. Boletin de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana. 1995;119(5):377–90.

Hudelson PM. ORS and the treatment of childhood diarrhea in Managua, Nicaragua. Soc Sci Med. 1993;37(1):97–103.

Ene-Obong HN, Iroegbu CU, Uwaegbute AC. Perceived causes and management of diarrhoea in young children by market women in Enugu State, Nigeria. J Health Popul Nutr. 2000;18(2):97–102.

Alam MB, Ahmed FU, Rahman ME. Misuse of drugs in acute diarrhoea in under-five children. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 1998;24(2):27–31.

Fischer Walker CL, Fontaine O, Black RE. Measuring coverage in MNCH: current indicators for measuring coverage of diarrhea treatment interventions and opportunities for improvement. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001385.

Emond A, Pollock J, Da Costa N, Maranhao T, Macedo A. The effectiveness of community-based interventions to improve maternal and infant health in the Northeast of Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2002;12(2):101–10.

Webb AL, Ramakrishnan U, Stein AD, Sellen DW, Merchant M, Martorell R. Greater years of maternal schooling and higher scores on academic achievement tests are independently associated with improved management of child diarrhea by rural Guatemalan mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(5):799–806.

Martinez H, Ryan GW, Guiscafre H, Gutierrez G. An intercultural comparison of home case management of acute diarrhea in Mexico: implications for program planners. Arch Med Res. 1998;29(4):351–60.

Kristiansson C, Gotuzzo E, Rodriguez H, Bartoloni A, Strohmeyer M, Tomson G, et al. Access to health care in relation to socioeconomic status in the Amazonian area of Peru. Int J Equity Health. 2009;8:11.

Langsten R, Hill K. Diarrhoeal disease, oral rehydration, and childhood mortality in rural Egypt. J Trop Pediatr. 1994;40(5):272–8.

Diarrhoeal Diseases Control Programme: diarrhoea morbidity and case management survey, Morocco. Weekly Epidemiological Record 1991, 66(13):89–91.

Morisky DE, Kar SB, Chaudhry AS, Chen KR, Shaheen M, Chickering K. Update on ORS usage in Pakistan: results of a national study. Pakistan J Nutr. 2002;1(3):143–50.

Nasrin D, Wu Y, Blackwelder WC, Farag TH, Saha D, Sow SO, et al. Health care seeking for childhood diarrhea in developing countries: evidence from seven sites in Africa and Asia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89(1 Suppl):3–12.

Bella H, Ai-Freihi H, El-Mousan M, Danso KT, Sohaibani M, Khazindar MS. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices related to Diarrhoea in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med. 1994;1(1):40–4.

Al-Mazrou YY, Aziz KM, Khan MU, Farag MK, Al-Shehri SN. ORS use in diarrhoea in Saudi children: is it adequate? J Trop Pediatr. 1995;41(Suppl 1):53–8.

Ketsela T, Asfaw M, Belachew C. Knowledge and practice of mothers/care-takers towards diarrhoea and its treatment in rural communities in Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 1991;29(4):213–24.

Mash D, Aschenaki K, Kedamo T, Walternsperger K, Gebreyes K, Pasha O, et al. Community and facility surveys illuminate the pathway to child survival in Liben Woreda, Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 2003;80(9):463–9.

Saha D, Akinsola A, Sharples K, Adeyemi MO, Antonio M, Imran S, et al. Health Care Utilization and Attitudes Survey: understanding diarrheal disease in rural Gambia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89(1 Suppl):13–20.

Mirza NM, Caulfield LE, Black RE, Macharia WM. Risk factors for diarrheal duration. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146(9):776–85.

Burton DC, Flannery B, Onyango B, Larson C, Alaii J, Zhang X, et al. Healthcare-seeking behaviour for common infectious disease-related illnesses in rural Kenya: a community-based house-to-house survey. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29(1):61–70.

Simpson E, Zwisler G, Moodley M. Survey of caregivers in Kenya to assess perceptions of zinc as a treatment for diarrhea in young children and adherence to recommended treatment behaviors. J Glob Health. 2013;3(1):10405.

Perez F, Ba H, Dastagire SG, Altmann M. The role of community health workers in improving child health programmes in Mali. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9:28.

Edet EE. Fluid intake and feeding practices during diarrhoea in Odukpani, Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 1996;73(5):289–91.

Omokhodion FO, Oyemade A, Sridhar MK, Olaseha IO, Olawuyi JF. Diarrhoea in children of Nigerian market women: prevalence, knowledge of causes, and management. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1998;16(3):194–200.

Ogunrinde OG, Raji T, Owolabi OA, Anigo KM. Knowledge, attitude and practice of home management of childhood diarrhoea among caregivers of under-5 children with diarrhoeal disease in Northwestern Nigeria. J Trop Pediatr. 2012;58(2):143–6.

Cooke ML, Nel ER, Cotton MF. Pre-hospital management and risk factors in children with acute diarrhoea admitted to a short-stay ward in an urban South African hospital with a high HIV burden. South Afr J Child Health. 2013;7(3):84–7.

Haroun HM, Mahfouz MS, El Mukhtar M, Salah A. Assessment of the effect of health education on mothers in Al Maki area, Gezira state, to improve homecare for children under five with diarrhea. J Family Community Med. 2010;17(3):141–6.

Taha AZ. Assessment of mother’s knowledge and practice in use of oral rehydration solution for diarrhea in rural Bangladesh. Saudi Med J. 2002;23(8):904–8.

Larson CP, Saha UR, Nazrul H. Impact monitoring of the national scale up of zinc treatment for childhood diarrhea in Bangladesh: repeat ecologic surveys. PLoS Med. 2009;6(11):e1000175.

Sood AK, Kapil U. Knowledge and practices among rural mothers in Haryana about childhood diarrhea. Indian J Pediatr. 1990;57(4):563–6.

Gupta N, Jain SK, Chawla U, Hossain S, Venkatesh S. An evaluation of diarrheal diseases and acute respiratory infections control programmes in a Delhi slum. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74(5):471–6.

Diarrhoeal disease control programme. Household survey of diarrhoea case management, Nepal. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1991;66(37):273–6.

Jha N, Singh R, Baral D. Knowledge, attitude and practices of mothers regarding home management of acute diarrhoea in Sunsari, Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2006;8(1):27–30.

Hoan LT, Chuc NTK, Ottosson E, Allebeck P. Drug use among children under 5 with respiratory illness and/or diarrhoea in a rural district of Vietnam. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(6):448–53.

Larrea-Killinger C, Munoz A. The child’s body without fluid: mother’s knowledge and practices about hydration and rehydration in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(6):498–507.

Granich R, Cantwell MF, Long K, Maldonado Y, Parsonnet J. Patterns of health seeking behavior during episodes of childhood diarrhea: a study of Tzotzil-speaking Mayans in the highlands of Chiapas, Mexico. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(4):489–95.

Ecker L, Ochoa TJ, Vargas M, Del Valle LJ, Ruiz J. Factors affecting caregivers’ use of antibiotics available without a prescription in Peru. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):e1771–1779.

Agha A, White F, Younus M, Kadir MM, Alir S, Fatmi Z. Eight key household practices of integrated management of childhood illnesses (IMCI) amongst mothers of children aged 6 to 59 months in Gambat, Sindh, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57(6):288–93.

Rasheed P. Perception of diarrhoeal diseases among mothers and mothers-to-be: implications for health education in Saudi Arabia. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(3):373–7.

Mwambete KD, Joseph R. Knowledge and perception of mothers and caregivers on childhood diarrhoea and its management in Temeke municipality, Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2010;12(1):47–54.

Buch NA, Hassan M, Bhat IA. Parental awareness and practices in acute diarrhea. Indian Pediatr. 1995;32(1):76–9.

Datta V, John R, Singh VP, Chaturvedi P. Maternal knowledge, attitude and practices towards diarrhea and oral rehydration therapy in rural Maharashtra. Indian J Pediatr. 2001;68(11):1035–7.

Sheetal V. Impact of education on rural women about preparing ORS and SSS: a study of the primary health centre, Uvarsad, Gandhinagar. Health Popul Perspect Issues. 2009;32(3):124–30.

Bolam A, Manandhar DS, Shrestha P, Ellis M, Costello AM. The effects of postnatal health education for mothers on infant care and family planning practices in Nepal: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1998;316(7134):805–11.

Adhikari P, Dhungel S, Shrestha R, Khanal S. Knowledge attitude and practice (KAP) study regarding facts for life. Nepal Med Coll J. 2006;8(2):93–6.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Christa Fischer-Walker and Cesar Victora for their helpful inputs on earlier drafts of this paper, and Peggy Gross for her technical assistance in developing literature search criteria.

This work was funded through a sub-grant from the U.S. Fund for UNICEF under the Countdown to 2015 for Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The funders had no role in the conceptualization of the paper or in the material presented.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JB and HN conceptualized the systematic review. EC developed the search criteria, conducted the systematic review, and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. JB, HN, and JP reviewed the search criteria and drafts of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

PubMed Search Terms. (PDF 68 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Carter, E., Bryce, J., Perin, J. et al. Harmful practices in the management of childhood diarrhea in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 15, 788 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2127-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2127-1