Abstract

Background

News media are key sources of information regarding tobacco issues, and help set the tobacco control policy agenda. We examined US news coverage of voluntarily smokefree restaurants and bars in locales without mandatory policies to understand how such initiatives are perceived.

Methods

We searched three online media databases (Access World News, Lexis Nexis, and Proquest) for all news items, including opinion pieces, published from 1995 to 2011. We coded retrieved items quantitatively, analyzing the volume, type, provenance, prominence, and content of news coverage.

Results

We found 986 news items, most published in local newspapers. News items conveyed unambiguous support for voluntarily smokefree establishments, regardless of venue. Mandatory policies were also frequently mentioned, and portrayed positively or neutrally. Restaurant items were more likely to mention health-related benefits of going smokefree, with bar items more likely to mention business-related benefits.

Conclusion

Voluntary smokefree rules in bars and restaurants are regarded by news media as reasonable responses to health and business-based concerns about worker and customer exposure to secondhand smoke. As efforts continue to enact comprehensive smokefree policies to protect all in such venues, the media are likely to be supportive partners in the advocacy process, helping to generate public and policymaker support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

News media are key sources of information about a variety of public health issues, including tobacco, and a high volume of tobacco-related news coverage is associated with negative views of and more accurate beliefs about smoking [1, 2]. The news media also help to advance public health policy, setting the policy agenda by singling out particular issues for discussion [3, 4]. Agenda setting communicates to the public and policymakers the relative importance of various issues based on the amount of media attention devoted to them [4]. It can increase public discourse about an issue and increase the likelihood of a policy response [5].

Researchers have examined media coverage of a range of tobacco topics [5–15]. However, no previous studies have examined the phenomenon of voluntary smokefree policies in restaurants and bars. Voluntary rules restricting smoking in restaurants and bars frequently precede passage of smokefree legislation [16]. While they are by nature less comprehensive and potentially less stable than mandatory policies [17], they may help create public support for legislation by increasing familiarity with and knowledge of the benefits of smokefree public places [16]. However, voluntary measures may stem from different motivations than mandatory policies, which are typically framed as public health interventions [18, 19]. For example, economic considerations, such as reduced cleaning costs or a desire to cater to a majority nonsmoking clientele may motivate restaurant and bar owners to prohibit smoking, rather than concerns about limiting workers’ and patrons’ exposure to a known carcinogen [20]. Similarly, patrons may appreciate smokefree restaurants more for eliminating an unpleasant smell than for protecting their health [18]. Greater knowledge of media coverage of voluntary smokefree measures may provide insight into how to enhance public and policymaker support for comprehensive smokefree legislation, particularly in the case of bars, which many Americans view as venues to which smoking is integral [21]. (There remains a disparity between the number of states with smokefree bar laws (32) versus smokefree restaurant laws (38)) [22].

In this paper, we explore US media coverage of voluntarily smokefree restaurants and bars from 1995-2011. We sought to learn how the media covered this phenomenon in general, including the motivations for and expected benefits of going smokefree voluntarily, and explored whether, and how, media coverage of smokefree restaurants differed from coverage of smokefree bars.

Methods

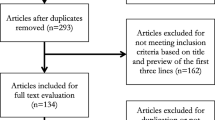

We searched three online media databases (Lexis Nexis, Proquest, and Access World News) for news items published between 1995 and 2011 concerning US restaurants or bars that had gone smokefree voluntarily (before the imposition of any local or state clean indoor air laws). The three databases covered 1381 news sources, including 999 local and national newspapers, 11 magazines, 61 newswires, 256 web-only news sources, 53 television network news broadcasts, and National Public Radio. We used a variety of search terms to locate news items, starting with general terms intended to capture all independent or chain restaurants and bars (including taverns and pubs) or restaurant/bar combinations that had voluntarily implemented smokefree indoor air policies (e.g., (voluntar* AND (smoking OR "smoke free")) AND (voluntar* AND (bar OR restaurant OR eatery OR cafe OR dining OR tavern OR pub)). We used retrieved items to identify more specific search terms (e.g., the names of particular restaurants which had gone smokefree). We stopped searching once no new items were found. We included items with nearly-identical content that were published in multiple news outlets in order to understand the reach of media coverage.

We coded news items through a collaborative, iterative process. Using an adaptation of a codebook from an earlier project that examined media coverage of retailers who had voluntarily ended tobacco sales [23], the authors created an initial coding sheet and piloted it on 10 news items.After discussion, we refined and edited the coding sheet and drafted coding instructions. Next, three coders (the second, third, and fourth authors) independently coded an overlapping set of 20 % (n = 201) of the items (chosen with a random number generator), checking in with one another and the first author early in the process to compare results, discuss discrepancies, and refine coding instructions.

We assessed inter-coder reliability of the overlapping sample using Gwet’s AC1 statistic. It is an improvement on the kappa (κ) statistic, which becomes unreliable without sufficient variety in coding [24]. For example, if on one item the correct code is “no” 90 % of the time, the resulting κ has a low value even when inter-rater agreement is high [25–27]. Like the κ statistic, AC1 has a value of 0-1, and can be interpreted in a similar manner. Each variable was tested and variables that did not achieve a value of .60 were not retained. Only one variable was not retained and not used in the analysis. Average inter-coder reliability for all retained variables was 0.833, which has been characterized as “almost perfect” agreement [28, 29].

After confirming inter-coder reliability with the overlapping sample [24], each coder independently coded one-third of the remaining (randomly assigned) news items. We also recoded the items coded early in the process to be consistent with the final version of the codebook. We coded story characteristics (i.e., news source, story type, date, photo, page number, word length, etc.) and content. For the purposes of this paper, we focused our analysis on content related to the overall impression of voluntary smokefree policies, overall customer reaction, health and business-related motivations and outcomes, evidence and authorities cited, and mention and portrayal of mandatory smokefree policies. In determining overall impression and overall customer reaction, we assessed support or not for smokefree policies as reflected in each news item as a whole; thus, for example, an item that included one opposition statement and seven statements of support was coded as supportive. We did not conduct significance testing because the items collected were not a random sample, and we are not extrapolating from them. Rather, we report the findings from the entire population of items meeting the search criteria [30].

This study has limitations. The news databases we searched are not comprehensive, although they cover a wide range of national and local newspapers. Our search terms, while comprehensive, may not have been exhaustive; thus, we may have failed to identify and include relevant news items in our study. We also chose to include nearly identical content published by different sources in order to capture the breadth of coverage; as a result, any similar content was coded multiple times. Our results, therefore, reflect all coverage that appeared, not unique stories.

Results

Characteristics of news items and trends over time

We found 986 news items published from 1995-2011 about restaurateurs and/or bar owners who voluntarily prohibited smoking on their premises; the vast majority were local newspaper articles (89.7 %) (daily or weekly newspapers serving a specific city or region, such as the San Francisco Chronicle), but sources also included national newspapers (newspapers, such as the New York Times, that circulate throughout the US), news wires, magazine articles, and web-based news sites (Table 1). News stories or features comprised the majority of items (71.1 %). Item length ranged from 26 (for brief blurbs) to 3527 words, with a median of 490 words. Most of the coverage concerned smokefree restaurants (65.6 %). 130 items (13.2 %) were duplicates, nearly identical wire service stories published in multiple local newspapers. (We conducted several analyses with duplicates removed, but the results did not differ markedly from those that included duplicates).

The volume of news coverage varied between 1995 and 2011 (Fig. 1). Starting in 2000, there was a trend of increasing coverage that peaked between 2005 and 2007, followed by declining coverage. In every year but two (2007 and 2011), news coverage of voluntarily smokefree restaurants exceeded that of voluntarily smokefree bars.

In newspapers, issues considered editorially important are likely to be given greater prominence – placed on the front page, the front page of a section, or accompanied by a photograph [31]. In our study, among items published in newspapers, 119 (13.3 %) appeared on the front page, 173 (19.4 %) appeared on the first page of a section (other than the section containing the front page), and 214 (24 %) had photos accompanying the articles.

Support for voluntary smoke-free restaurant and bar policies

News coverage was overwhelmingly supportive of these voluntary policies (Table 2). Among all non-opinion news items, the overall impression of restaurant and bar owners’ decision to go smokefree was largely positive (78 %); among editorials, letters to the editor, and columns, nearly all (97.1 %) expressed support for such decisions. For example, one letter writer advocated for voluntary smokefree policies on the grounds that it was good for business, noting that “the first nonsmoking sports bar to open in Ft. Collins, Colo. is still STANDING ROOM ONLY (emphasis in original) even on weeknights after almost two years” [32]. There was also relatively limited mention of any arguments used to oppose voluntary smokefree policies (31.1 %) (e.g., an assumption that the business would lose money or the assertion that alternatives such as ventilation or separate sections were preferable). Customer reaction, when cited, was less overwhelmingly supportive, but nonetheless mostly positive (54.3 %) or mixed (34.2 %), perhaps reflecting the journalistic convention of seeking “both sides” of a story. For example, the manager of a restaurant in southern California described the responses to his newly-adopted smoke-free policy: “A few smokers felt their rights were being trampled”, but “that’s been truly a rare occurrence” [33].

Health and business-related motivations and outcomes

News items referenced a variety of health and/or business-focused reasons for and likely consequences of restaurants and bars going smokefree voluntarily. One of the most common reasons given for implementing voluntary smokefree policies was to promote health (e.g., of customers or employees) (36.6 %) (Table 2); however, taken together, business reasons, such as accommodating nonsmoking customers or reducing cleaning costs, were more commonly cited (56.8 %). For example, a restaurant owner in Michigan reportedly “put an end to lighting up” because “he was tired of watching customers walk out the door because of the smoke” [34]. A restaurant manager in North Dakota noted that going smokefree would save on such regular expenses as cleaning “the blackened filters of the ventilation system” [35]. Similarly, when discussing the potential positive impacts of going smokefree, news items more often cited benefits that would accrue to the business, such as an improved image or a gain (or at least no change) in patronage (56.2 %), rather than public health benefits such as a reduction in smoking or improved health (27.0 %). For example, an Idaho bar owner said that “voluntarily making his bars smoke-free has been a boon for business. … [It] has meant lower labor costs, no clogged urinals and no cigarette burns on the furniture” [36].

Evidence and sources quoted

In print articles, direct quotes are more influential on readers’ impressions of issues than paraphrased quotes [37]; thus, we coded sources in news items who were directly quoted. Government officials (including elected officials and heads of public health departments) and tobacco control advocates, while not quoted regularly, were quoted more often than representatives of the tobacco industry and its allies, restaurant and bar associations (Table 2) [38, 39]. Elected officials were often quoted debating the pros and cons of legislation mandating smokefree restaurants or bars. For example, one North Dakota State Representative discussed constituent input about smokefree legislation, noting that she had “not had the type of push for bars (to ban smoking) that we got for the restaurants from the public” [40]. Tobacco control advocates typically praised businesses for going smokefree. When two popular chain restaurants went smokefree, John Kirkwood, the President and CEO of the American Lung Association, offered his congratulations in a 2005 wire service article, noting that “[t]his shows that they are concerned about the health of their employees and customers” [41].

Nearly 40 % of articles referenced scientific evidence about tobacco, including its deadly disease effects, to help provide context for business owners’ decisions to prohibit smoking in their establishments (Table 2). For example, an article featuring a restaurant with a bar that went smokefree in upstate New York noted that “Statistics show that for every 8 smokers killed by tobacco, 1 nonsmoker also dies” [42]. We examined whether mention of scientific evidence about tobacco increased after the 2006 publication of the Surgeon General’s report on secondhand smoke [43]; we found no such increase.

Coverage of mandatory policies

With a steady rise in the number of smokefree laws over the period of study [17], it was unsurprising that a majority of news items (70.5 %) referred to one or more laws governing smoking (typically, but not exclusively, in restaurants or bars) (Table 2). Given the high level of support for voluntary rules in news items, we expected support for mandatory policies to be lower; while this was the case, portrayals of mandatory policies were still more likely to be mixed or neutral (55.5 %) or even positive (33.1 %) than entirely negative (11.4 %). A common criticism of such policies was that they represented governmental inconsistency and infringed on business owners’ rights (mentioned in 33.8 % of stories that cited mandatory policies). One bar owner in Corpus Christi, Texas who voluntarily imposed a smoke-free rule on his premises exemplified this sentiment: “I’m not sure the government should tell people what they can and cannot do. As a business owner, tobacco is a legal drug. If it’s so bad, why don’t they ban it altogether?” [44].

Restaurants versus bars

Given that smokefree bars appear to be less widely accepted by the public than smokefree restaurants [21], we compared coverage of the two venues to assess whether this was reflected in news coverage. (We combined news items concerning bars and restaurant/bar combinations into the same category (bars) because it seemed reasonable to assume that an establishment with both a restaurant and bar was likely to share many features of a stand-alone bar and to elicit a similar public response when going smokefree.) First, we examined characteristics of news items for each venue. The only notable differences concerned the type of news story and media region. Editorials and news items were more common among bar-related items (61, 30.3 %) than restaurant-related items (49, 7.6 %), and, among all regions, the Midwest claimed nearly half of all bar-related items (100, 49.8 %).

Next, we examined the slant of coverage. Both opinion and non-opinion news items were overwhelmingly supportive, regardless of venue (Table 2). Reported customer reaction was also quite similar for both bars and restaurants, with the majority clustered in the positive or mixed categories rather than purely negative. One notable difference in the slant of coverage of the two venues concerned mandatory smokefree policies for restaurants or bars. Bar-related items were more likely to mention such policies (168, 83.6 % versus 404, 62.4 %), and to portray them favorably (44.0 % versus 31.2 %; Table 2). For example, in an article that reported on a smoke-free bar in Bowling Green, Kentucky, a tobacco control advocate noted that “she’s found that more people in the city would favor a citywide smoking ban than not” [45].

We also explored venue-related differences in motivations for and expected benefits of going smokefree. Overall, restaurant items were more likely than bar items to cite any reason for going smokefree, including health (38.2 % versus 22.9 %), public health advocacy (20.7 % versus 7.5 %), or business considerations (58.7 % versus 42.8 %) (Table 2). Restaurant items were also more likely to mention health-related benefits of going smokefree (28.1 % versus 16.4 %), while bar items were more likely to mention business-related benefits (76.6 % versus 50.9 %) (Table 2). For example, when Mike Scanlon, owner of Applebee’s and Johnny Carino’s chains, announced that all of his restaurants had gone smoke-free, he explained, “We’re not killing employees anymore” [46]. A Wyoming bar owner stressed the economic benefit of going smokefree: “It actually has been going incredibly well. Our business is up since we did it” [47].

Finally, we examined the evidence and authorities cited in restaurant versus bar items. While the likelihood of citing various authorities did not differ markedly, restaurant-related items were twice as likely to mention scientific evidence about tobacco, including its disease effects (40.2 % versus 20.4 %) (Table 2).

Discussion

Restaurant and bar owners’ decisions to voluntarily go smokefree in their establishments were newsworthy events, reported on frequently over the 17-year period of the study (although with a decline in coverage starting in 2008). They were primarily the subject of local media attention, most likely because the majority of businesses that received coverage were local, independent restaurants or bars; a change in their smoking policy was likely to be of interest to local residents. Some of the coverage also occupied prominent positions in newspapers (e.g., on the front page or the first page of a section) or had an accompanying photograph, likely to draw readers’ attention, suggesting that the topic was considered not just of interest but likely to be important to community members.

Voluntarily smokefree restaurants and bars were a topic more common in the media in the Midwest and the south, regions that have been slower to introduce smokefree restaurant and bar laws [48] and are thus perhaps more reliant on voluntary measures. However, despite regular media attention over the period, coverage peaked in the mid-2000s, possibly because interest waned over time, as smokefree restaurants and bars became less novel (and hence less newsworthy) [49], or because fewer voluntary smokefree rules were introduced after 2007, replaced by smokefree legislation or reaching a saturation point among business owners.

Surprisingly, on several measures, news items conveyed unambiguous support for voluntarily smokefree establishments, regardless of venue. Public ambivalence about smokefree bars [21] was clearly not reflected in the media. It did not appear to be the case that this support hinged on the voluntary nature of the policy, as bar-related items also frequently mentioned mandatory policies, and typically portrayed them in a positive or neutral fashion. Instead, the high level of support for voluntarily smokefree bars in media coverage may have been explained by the inclusion of pragmatic business-related reasons for and expected benefits of going smokefree, coupled with changes in social norms about tobacco use more generally.

There were, however, some notable venue-specific differences in coverage. Smokefree bars generated more editorials and op-eds than smokefree restaurants, suggesting that editors regarded smokefree bars as more novel or worthy of more interpretation for readers [8], possibly because they were considered more likely than smokefree restaurants to generate controversy. Comparing coverage of the two venues also revealed some important differences in health and business motivations for and outcomes of going smokefree, with health considerations playing a larger role in restaurant-related items. Restaurant items were also twice as likely to cite scientific evidence about tobacco, including its negative disease effects. It may be more normative for restaurant owners to cite health concerns as reasons for going smokefree. Restaurants serve adults and children, and at least some promise healthful products; by contrast, bars are adults-only venues already associated with a (potentially) hazardous behavior (drinking).

Conclusion

Media coverage not only educates readers about the salience of particular issues, but also helps them interpret and respond to those issues [1, 4, 50–52]. The American news coverage we analyzed conveyed to readers both that voluntarily smokefree bars and restaurants were an important issue, and that they were a reasonable response to health and business-based concerns about worker and customer exposure to secondhand smoke. In addition, most media coverage did not imply that voluntary policies were preferable to mandatory policies. As efforts continue in the U.S. to enact comprehensive smokefree policies to protect all workers and customers in such venues, the media are likely to be supportive partners in the advocacy process, helping to generate public and policymaker support.

References

Smith KC, Wakefield MA, Terry-McElrath Y, Chaloupka FJ, Flay B, Johnston L, et al. Relation between newspaper coverage of tobacco issues and smoking attitudes and behaviour among American teens. Tob Control. 2008;17(1):17–24.

Dunlop SM, Romer D. Relation between newspaper coverage of 'light' cigarette litigation and beliefs about 'lights' among American adolescents and young adults: the impact on risk perceptions and quitting intentions. Tob Control. 2010;19(4):267-273.

Kingdon J. Agenda, alternatives, and public policies. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co.; 1984.

McCombs ME, Shaw DL. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin Q. 1972;36(2):176–87.

Caburnay CA, Kreuter MW, Luke DA, Logan RA, Jacobsen HA, Reddy VC, et al. The news on health behavior: coverage of diet, activity, and tobacco in local newspapers. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(6):709–22.

Smith KC, McLeod K, Wakefield M. Australian letters to the editor on tobacco: triggers, rhetoric, and claims to legitimate voice. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1180–98.

Smith KC, Siebel C, Pham L, Cho J, Singer RF, Chaloupka FJ, et al. News on tobacco and public attitudes toward smokefree air policies in the United States. Health Policy. 2008;86(1):42–52.

Smith KC, Wakefield M. Textual analysis of tobacco editorials: how are key media gatekeepers framing the issues? Am J Health Promot. 2005;19(5):361–8.

Smith KC, Wakefield M. Newspaper coverage of youth and tobacco: implications for public health. Health Commun. 2006;19(1):19–28.

Smith KC, Wakefield M, Edsall E. The good news about smoking: how do U.S. newspapers cover tobacco issues? J Public Health Policy. 2006;27(2):166–81.

Durrant R, Wakefield M, McLeod K, Clegg-Smith K, Chapman S. Tobacco in the news: an analysis of newspaper coverage of tobacco issues in Australia, 2001. Tob Control. 2003;12 Suppl 2:ii75–81.

Dorfman L, Cheyne A, Gottlieb MA, Mejia P, Nixon L, Friedman LC, et al. Cigarettes become a dangerous product: tobacco in the rearview mirror, 1952-1965. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):37–46.

Wackowski OA, Lewis MJ, Delnevo CD, Ling PM. A content analysis of smokeless tobacco coverage in U.S. newspapers and news wires. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(7):1289–96.

Long M, Slater MD, Lysengen L. US news media coverage of tobacco control issues. Tob Control. 2006;15(5):367–72.

Nelson DE, Pederson LL, Mowery P, Bailey S, Sevilimedu V, London J, et al. Trends in US newspaper and television coverage of tobacco. Tob Control. 2015;24(1):94-99.

Linnan LA, Weiner BJ, Bowling JM, Bunger EM. Views about secondhand smoke and smoke-free policies among North Carolina restaurant owners before passage of a law to prohibit smoking. N C Med J. 2010;71(4):325–33.

Sanders-Jackson A, Gonzalez M, Zerbe B, Song AV, Glantz SA. The pattern of indoor smoking restriction law transitions, 1970-2009: laws are sticky. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):e44–51.

Heim D, Ross A, Eadie D, MacAskill S, Davies JB, Hastings G, et al. Public health or social impacts? A qualitative analysis of attitudes toward the smoke-free legislation in Scotland. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(12):1424–30.

Magzamen S, Charlesworth A, Glantz SA. Print media coverage of California's smokefree bar law. Tob Control. 2001;10(2):154–60.

Johnson HH, Becker C, Inman L, Webb K, Brady C. Why be smoke-free? A qualitative study of smoke-free restaurant owner and manager opinions. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11(1):89–94.

King BA, Dube SR, Tynan MA. Attitudes toward smoke-free workplaces, restaurants, and bars, casinos, and clubs among U.S. adults: findings from the 2009-2010 national adult tobacco survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(8):1464–70.

States, commonwealths, and municipalities with 100 % smokefree laws in non-hospitality workplaces, restaurants, or bars [http://www.no-smoke.org/pdf/100ordlist.pdf]

McDaniel PA, Offen N, Yerger VB, Malone RE. “A Breath of Fresh Air Worth Spreading”: media coverage of retailer abandonment of tobacco sales. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):562–9.

Gwet K. Computing inter-rater reliability and its variance in the presence of high agreement. Br J Mathemat Statist Psychol. 2008;61:29–48.

Feinstein AR, Cicchetti DV. High agreement but low kappa: I. The problems of two paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(6):543–9.

Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T, Wedding D, Gwet KL. A comparison of Cohen's Kappa and Gwet's AC1 when calculating inter-rater reliability coefficients: a study conducted with personality disorder samples. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:61.

Baethge C, Franklin J, Mertens S. Substantial agreement of referee recommendations at a general medical journal--a peer review evaluation at Deutsches Arzteblatt International. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e61401.

Landis RJ, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical variables. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–77.

Munoz SR, Bangdiwala SI. Interpretation of Kappa and B statistics measures of agreement. J Appl Stat. 1997;24(1):105–12.

Glantz SA. Primer of Biostatistics. 7th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Medical; 2011.

Booth A. The recall of news items. Public Opin Quart. 1970;34(4):604–10.

LeBoeuf J. Need smoke-free bars. Chicago Daily Herald. Chicago, IL. 1997:15.

Beeman D. Ban on smoking: Fight or switch? Area restaurants are taking different tacks toward a new law that has some smokers up in arms. Riverside, CA. Press-Enterprise. 1995:B1.

York S. Push for workplace ban sears smokers. Flint Journal. 2009:A1.

DeLage J. A smoke-free switch. Grand Forks Herald. Grand Forks, ND. 1998:5.

Webb A. Boise is divided on proposed smoking ban - Comments Wednesday ranged from skepticism to supporting the law. Boise, ID: Idaho Statesman; 2011.

Gibson R, Zillmann D. The impact of quotation in news reports on issue perception. J Mass Commun Q. 1993;70(4):793–800.

Dearlove JV, Bialous SA, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry manipulation of the hospitality industry to maintain smoking in public places. Tob Control. 2002;11(2):94–104.

Ritch WA, Begay ME. Strange bedfellows: the history of collaboration between the Massachusetts Restaurant Association and the tobacco industry. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(4):598–603.

State marks a year of no smoking in restaurants. Are bars next? In: Associated Press. 2006.

KFC and Pizza Hut announce no smoking policy. In: Business Wire. 2005.

Wood S. Report targets smoke in eateries. Albany, NY: Times Union; 2001. p. B4.

Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006.

Libby L. Bar owner prohibits smoking - But choice should not be mandated, John Gordon says. Corpus Christi, TX: Caller-Times; 2004. p. A1.

Adams R. Smoke-free jails: local policy change coming - Warren County jail to bar smoking. Bowling Green, KY: Daily News; 2006.

Pospeschil J. Restaurateur touts smoke-free policy - Owner of 90 restaurants speaks to crowd at WIU. Peoria, IL: Journal Star; 2007. p. B5.

Health Department expects more restaurants, bars to go smoke-free. In Associated Press. 2005.

Chronological Table of U.S. Population Protected by 100 % Smokefree State or Local Laws [http://no-smoke.org/pdf/EffectivePopulationList.pdf]

Gans H. Deciding what's news. New York: Pantheon; 1979.

McCombs ME, Shaw DL. The evolution of agenda-setting research: twenty-five years in the marketplace of ideas. J Commun. 1993;43(2):58–67.

Wallack L, Dorfman L. Media advocacy: a strategy for advancing policy and promoting health. Health Educ Q. 1996;23(3):293–317.

Wallack L, Dorfman L, Jernigan D. Media advocacy and public health: power for prevention. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993.

Hladky G. 200 more state restaurants go smoke-free during 1997. New Haven, CT: New Haven Register; 1997. p. A5.

Kreimer P. Bar air is 10 times worse here. Covington, KY: Kentucky Post; 2007. p. A1.

Stedman L. Activists dispute effects of smoking bans. Ft. Wayne, IN: Journal Gazette; 1998. p. 1A.

Opinion. In Daily News-Miner. Fairbanks, AK; 2003.

Hitzeman C. Patrons show disinterest in smoke ban. Ft. Wayne, IN: Journal Gazette; 1998. p. 4A.

Lee R. Can cafe survive smoke free? Oklahoma City, OK: Daily Oklahoman; 1999. p. 1.

Parker K. New guide lists smoke-free restaurants. Tampa, FL: Tampa Tribune; 1995. p. 1.

Sussman L. Breath of fresh air - 2 restaurants that just went smoke-free are finding that business is stable - or even rising. Milwaukee, WI: Journal Sentinel; 2008. p. 1.

Rocker M. More eating establishments snuffin' puffin': The number of "no smoking" signs in Auburn restaurants grows. Syracuse, NY: Herald-Journal; 1997. p. B1.

Clark S. Eating out column: Smoke-free restaurants increasing. Ft. Wayne, IN: Journal Gazette; 1997. p. 1D.

Smoking ban sparks debate. Utica Observer-Dispatch. Utica, NY. 2003:1.

Rolling Meadows Tobacco Information and Prevention Committee. Kudos to those restaurants that banned smoking. Chicago, IL: Daily Herald; 1999. p. 1.

Garifo C. Many eateries smoke-free now. Watertown, NY: Daily Times; 2003. p. D8.

Piet E. Smoke-free by choice. Grand Rapids, MI: Grand Rapids Press; 2008. p. C1.

Neergaard L. Public smoking bans urged - Surgeon General says 'debate over' on health hazards. Ft. Wayne, IN: Journal Gazette; 2006. p. 10A.

Burstein J. Smoking ban for eateries proposed - City Council discussion set. Tucson, AZ: Arizona Daily Star; 1999. p. 1A.

La Crosse is latest city to pass smoke-free dining law. In Associated Press. 1999.

Neergaard L. Study affirms secondhand smoke is a killer. Ocala, FL: Star-Banner; 2006.

Dadigan M. Restaurants put in on menu early: Smokers need to light up outside - The indoor smoking ban doesn't take effect until July 1, but many area restaurants are enforcing the rule now. Vero Beach, FL: Press Journal; 2003. p. A1.

Frothingham K. Going smoke-free is being done right away. Bowling Green, KY: Daily News; 2010.

Tabor K. Smoke-free bar and grill set to open in Enterprise. Enterprise, AL: Ledger; 2008.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the National Cancer Institute, grant number R01 CA143076. The funder played no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. We would like to thank Vera Nelson for help with data entry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PM helped design the study, oversaw the coding and analysis, wrote the second draft of the paper and edited all subsequent drafts. NO coded, analyzed, and managed the data, wrote the first draft of the paper and edited subsequent drafts. VY and SF coded the data and edited paper drafts. RM conceptualized the study, oversaw the creation of the initial codebook, and edited all paper drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

McDaniel, P.A., Offen, N., Yerger, V. et al. “Tired of watching customers walk out the door because of the smoke”: a content analysis of media coverage of voluntarily smokefree restaurants and bars. BMC Public Health 15, 761 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2094-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2094-6