Abstract

Background

Although obesity among immigrants remains an important area of study given the increasing migrant population in Australia and other developed countries, research on factors amenable to intervention is sparse. The aim of the study was to develop a culturally-competent obesity prevention program for sub-Saharan African (SSA) families with children aged 12–17 years using a community-partnered participatory approach.

Methods

A community-partnered participatory approach that allowed the intervention to be developed in collaborative partnership with communities was used. Three pilot studies were carried out in 2008 and 2009 which included focus groups, interviews, and workshops with SSA parents, teenagers and health professionals, and emerging themes were used to inform the intervention content. A cultural competence framework containing 10 strategies was developed to inform the development of the program. Using findings from our scoping research, together with community consultations through the African Review Panel, a draft program outline (skeleton) was developed and presented in two separate community forums with SSA community members and health professionals working with SSA communities in Melbourne.

Results

The ‘Healthy Migrant Families Initiative (HMFI): Challenges and Choices’ program was developed and designed to assist African families in their transition to life in a new country. The program consists of nine sessions, each approximately 1 1/2 hours in length, which are divided into two modules based on the topic. The first module ‘Healthy lifestyles in a new culture’ (5 sessions) focuses on healthy eating, active living and healthy body weight. The second module ‘Healthy families in a new culture’ (4 sessions) focuses on parenting, communication and problem solving. The sessions are designed for a group setting (6–12 people per group), as many of the program activities are discussion-based, supported by session materials and program resources.

Conclusion

Strong partnerships and participation by SSA migrant communities enabled the design of a culturally competent and evidence-based intervention that addresses obesity prevention through a focus on healthy lifestyles and healthy families. Program implementation and evaluation will further inform obesity prevention interventions for ethnic minorities and disadvantaged communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation reported that, at 26.8%, sub-Saharan Africa has the highest prevalence of undernourishment, representing 234 million individuals who suffered from hunger in the 2010–2012 period and a growth of 64 million in the last 2 decades [1]. However, upon migration to industrialised countries, sub-Saharan African migrants are at increased risk of obesity and obesity-related diseases [2-5]. Numerous factors have been associated with the drastic increase in migrants’ body mass index (BMI), one of which is acculturation [6].

Acculturation refers to the phenomenon through which migrant populations adopt the cultural patterns (e.g., values, behaviours, norms, attitudes and beliefs) of their host society whilst perhaps maintaining aspects of their own culture to varying degrees [7]. In fact, emerging evidence suggests that there is an association between acculturation and overweight and obesity among migrant children and adults from low-moderate income countries to industrialised countries [6,8-11]. However, the prevalence of overweight and obesity is significantly lower among migrants who maintain some elements of their traditional cultural practices [6,12,13].

Although obesity remains an important area of study given the increasing migrant population in Australia and other developed countries, research on factors amenable to intervention is sparse. Most importantly, sub-Saharan African migrants are under-represented in obesity related research programs due to their low health literacy, poor English proficiency, and other cultural barriers. Studies seeking to determine socio-cultural factors to be included in obesity prevention programs targeting marginalised migrant communities are urgently needed. Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop a culturally-competent obesity prevention program for sub-Saharan African families with children aged 12–17 years using a community-partnered participatory approach.

Methods

Program development theory

The cultural competence framework was used to guide the development of the program. Cultural competence refers to “a set of congruent behaviours, attitudes and policies that come together in a system, agency or among professionals and enable that system, agency or those professions to work effectively in cross-cultural situations” [14]. Cultural competence is not just about awareness of cultural differences, but the capacity of the system to improve health through the integration of culture into program delivery [15]. Therefore, cultural competence in health and research refers to the ability of researchers and health practitioners to take into account the culture and diversity of the target population when developing a health promotion program, from the conception of the research ideas to the conduct of the research and the dissemination and application of the research findings. In this sense, cultural competence offers both a conceptual and practical approach to developing a culturally-competent health promotion program.

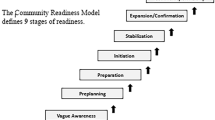

Sawyer and colleagues [16] have identified three strategies to achieve cultural competence in research: cultural knowledge, sensitivity, and collaboration. Gibbs and colleagues go further, proposing nine complementary strategies to achieve cultural competence in research [17] focusing on stages of research implementation: 1) forming partnership, 2) defining the research questions, 3) identifying data sources and target populations, 4) appointing staff, 5) recruiting participants, 6) data collection, 7) data analysis and evaluation, 8) reporting and disseminating, and 9) using the findings to develop an intervention. At each research stage, the authors provide examples of culturally competent practices that maximise participation among ethnic minorities and disadvantaged communities. However, there are some similarities and overlaps in these cultural competence models in terms of contents and application. We integrated and synthesised the different models to develop a cultural competence framework comprising 10 strategies [17], which informed the development of the program (Table 1). The development of the intervention used a trans-generational psycho-educational approach to obesity related behaviours. It included education sessions focused on healthy lifestyles in a new environment, and it addressed the intergenerational acculturation gap through a focus on parenting, communication and problem solving within the family.

Community participatory approach

An interactive community-partnered participatory approach was adopted, whereby the intervention was developed in collaborative partnership with communities, and community members were recruited and trained to participate in all aspects of the project implementation [18,19]. Effective engagement with the community of interest is critical, both to maximise the relevance and acceptance of the developed program [18,19]. This participatory approach was sustained through the mobilization of the African Review Panel, established as part of the African Migrant Capacity Building and Performance Appraisal framework [20-24]. Panel members were either nominated by their respective communities or recruited for their knowledge and expertise through community health workers and African community organisations’ networks. As in previous work, the panel acted as the study’s community-based steering committee as well as overseeing community mobilization and recruitment for the pilot studies, the scoping projects that informed the intervention [20-24] and the intervention components’ mapping study [25]. The panel also assisted the research team in interpretation and dissemination of the pilot and mapping study results within the community, and participated in the development and revision of the program outline, sessions and materials. Recently, the African Review Panel has been expanded to form part of the Child Obesity Prevention Advisory Council to assist in assessing the community readiness to engage with obesity prevention interventions in a program of research funded by the Australian government.

Target population and the program development process

The target population was families with children aged 12–17 years (see proposed mode of implementation below). Our previous research in this subpopulation shows that sub-Saharan African children and adolescents are at increased risk of obesity, but factors predisposing them to obesity are not yet well understood [6,20-27]. The project development was therefore designed to extend the evidence base through three phases. In Phase 1, we sought to qualitatively describe obesity, its risk factors, and how to improve the health of African families in Melbourne. Three pilot studies were carried out during 2008 and 2009 which included focus groups, interviews, and workshops with African parents, teenagers and health professionals [21,24]. Analyses revealed that the main drivers of obesity among sub-Saharan African children were related to intergenerational differences in parenting beliefs, family functioning, health literacy and lifestyle in a new culture.

In the second phase, a survey was conducted among African teenagers and their parents living in Melbourne to quantify various aspects of their health (including BMI, acculturation, food habits, parenting styles, and family functioning). The first survey was exploratory in nature and sought to test the recruitment approaches, to evaluate the application of parenting and family functioning scales, and to identify aspects of parenting and family functioning associated with obesity [23]. The study involved a total of 208 participants (104 parents and 104 offspring). Obesity emerged as a significant health issue; inconsistent discipline and lack of parental supervision were responsible for a significant proportion of variance in children’s BMI, which supported findings in Phase 1. The African Review Panel facilitated dissemination of these findings to the community, and four workshops were subsequently conducted to identify factors amenable to intervention. Using the Analysis Grid for Elements Linked to Obesity (ANGELO) framework [28], community members prioritized health behaviours, skill and knowledge gaps, and environments for change to be included in family-based childhood obesity prevention programs. The family priorities fell into four categories: behaviours for change; health knowledge gaps; health literacy and skills for better health; and home/family environments [25]. Results from the ANGELO workshops were helpful for indicating the types of strategies that might be helpful for the community and also highlighted low health literacy, particularly amongst parents, which was a barrier to health promotion and information-seeking for the community.

Finally, the development of the program outline and program materials involved a number of steps. Informed by findings from Phases 1 and 2, literature reviews, and community consultations through the African Review Panel, a draft program outline was developed and presented in two separate community forums with African community members and health professionals working with African communities in Melbourne. The first forum was conducted at a community event in December 2011 to celebrate the African Review Panel’s contribution to the project, disseminate findings from Phases 1 and 2 and gather feedback on the draft program outline. The second forum, in March 2012, provided other African community members with an opportunity to hear the program results to date and provide feedback on the draft program plan with the assistance of bilingual workers. Both forums were effective in obtaining useful feedback that informed additional community consultation and finalisation of the final program, ‘The Healthy Migrant Families Initiative: Challenges and Choices’ (HMFI).

Education materials to accompany the program were developed and informed by academic and grey literature, consultations with parenting experts, the research team, nutrition, and health professionals working with African families, the African Review Panel, and health providers to the African communities in Melbourne.

Ethical approvals for all phases of the project were obtained from Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee and/or Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Program overview

The Healthy Migrant Families Initiative: Challenges and Choices program was designed to assist African families in their transition to life in a new country, by providing them with culturally sensitive and relevant training about healthy eating, active living, and communication and problem solving within the family unit. The goal of the intervention was to promote healthy eating and physical activity levels among children by strengthening family cohesion, enhancing family resilience, and promoting whole family lifestyle change. The program content consists of nine sessions, each approximately 1½ hours in length, which are divided into two modules based on their topic. The first module ‘Healthy lifestyles in a new culture’ (5 sessions) focuses mainly upon healthy eating, but also touches on active living and healthy body weight. The second module ‘Healthy families in a new culture’ (4 sessions) focuses on parenting, communication and problem solving. The session titles, purposes and key messages, and activities belonging to each module are presented in Table 2.

Program implementation

The sessions are designed to run in a group setting, as many of the program activities are discussion-based. Ideally, a group would have a minimum of six participants and up to 12 participants, to allow greater diversity in the group discussions. Though the session materials and program resources (refer to ‘Program resources and session materials’) are comprehensive, consistent with the cultural competence framework, the sessions should ideally be run by qualified bilingual health professionals such as dieticians or nurses, family support workers, and family counsellors who have experience working with African migrant families (or from the target communities for tailoring purpose). For instance, the ‘lifestyles’ module should be run by an Accredited Practising Dietician or nutritionist and the ‘families’ module should be run by a qualified social worker or parenting educator. Facilitators would be expected to become familiar with the program and program resources. If the facilitator is not multilingual in the languages of the program participants, a bilingual interpreter will be required at the sessions.

Several key resources have been developed to ensure that the HMFI is run consistently across differing groups and settings, and by different facilitators. The resources cover the following materials:

For participants and facilitators

-

1.

‘Session PowerPoint Slides’ – one set of slides per session; to be projected onto a wall or screen whilst running the sessions to serve as a visual aid

-

2.

‘Activity materials’ – various materials to assist the participants in their learning, including:

-

Picture cards of food, ingredients and relevant nutritional information – cards to facilitate discussion about the healthfulness of different foods and meals

-

Session summaries – summary sheet of each session for the participants to take home and share with their families

-

Other educational aids – healthy food pyramids adapted to include common traditional African foods for each participant to keep at home, and wallet-sized laminated food choice decision aids for use at the supermarket

-

For facilitators only

-

1.

‘Instruction Manual’ – a resource comprising an overview of the program and the relevant resources for running the program and a reference point for program implementation

-

2.

‘Facilitators Manual’ – the ‘go-to-guide’ for facilitators about how to conduct the HMFI program. It outlines the role and responsibilities of the facilitator, summarises each session, and provides instructions and guidance for facilitating the sessions and optimising discussion e.g. communication types, how to optimise discussion, how to avoid barriers to communication, how to use active listening, adult education principles, safety and ethical considerations (e.g. safety procedures, privacy and confidentiality)

-

3.

‘Session Guide’ – provides useful information for facilitators about how to run each session including discussion suggestions, activities, time for each session and activity, and background information regarding the facilitation materials.

Discussion

This is the first study to develop a culturally competent obesity prevention program for sub-Saharan African migrant families in Australia. The developed program addresses two main components: healthy lifestyles and healthy families. The intervention is designed to be delivered to parents for three reasons: 1) to address the intergenerational acculturation gap, 2) to maximise the effect of parental involvement; and 3) to develop cultural competence strategies that maximise community ownership of the program.

Various studies have observed a dyadic acculturative stress resulting from differing pace of acculturation between migrant parents and their offspring, with children acculturating faster than their parents. The acculturation gap-distress hypothesis stipulates that when immigrant parents and children acculturate at different pace (e.g. inter-generational acculturation gap), the main outcomes include migrant parents and their children holding different values and preferences which often clash, family conflict as well as youth maladjustment [29,30]. It has been shown that improving parent–youth relationship quality helps youths cope more effectively with the stresses associated with adolescence and makes them responsive to positive parental influence related to a healthy lifestyle as well as a healthy body image and a healthy relationship with food [31-34]. In addition, evidence shows that parents and carers have a long-lasting impact on their child’s lifestyle behaviours throughout their life [35]. Parental support correlates with participation in physical activity, family commensality, food decision making, and family communication, while effective parenting and family cohesion offset vulnerability due to low socio-economic status (SES) [36]. Good parenting skills, positive family functioning, and higher parental control negate the deleterious effects of low SES on children [37]. Most importantly, there is emerging evidence suggesting that the success of family-based obesity prevention and treatment programs is greater when the focus is on training parents and maximising their involvement and influence at the household level; and when parents were the exclusive agents of change the results were superior to the conventional approach [38-40].

The intervention was developed in partnership with the community, and culturally competent strategies to sustain their participation and maximise their ownership of the program have been provided. Culturally tailored interventions should respect cultural practices, encourage retention of healthy traditional food practices, and work with people to identify ways by which they can modify their traditional foods to make manageable healthy changes. They should also identify and enlist influential family members, in particular those who shop for and prepare the food [41]. Both of those recommendations play a key role in the HMFI program – parents, as the food “gatekeepers” within the family are encouraged to attend the program sessions, and the program sessions will cater to different levels of acculturation by focusing upon Australian and traditional African foods. The proposed model is consistent with best practice in community partnership and how it relates to public health [42].

There are some limitations worth outlining. The paper provides a description of a best practice approach to developing interventions that would be culturally relevant and acceptable to immigrant and other ethnic minority groups. The described process adopted a culturally competence framework and would be well-suited to immigrant or other ethnic minority groups when researchers and practitioners are interested in developing culturally competent programs. Nevertheless, the paper is not about the evaluation of the program as we do not yet have data on the program implementation, tailoring process, and program efficacy. A randomised controlled trial is planned in the near future to evaluate the intervention’s impact on primary outcome (child body mass index) and secondary outcomes (parenting style, family functioning, food habits, level of physical activity). The evaluation will also shed light on the steps required to tailor the intervention to other culturally and linguistically diverse populations (e.g. evaluating implementation-related factors such as considerations that need to be made before and during implementation of the program, things that work/ don’t work for mobilising participants, keeping participants engaged in the sessions, and how the program sessions should be delivered in a culturally appropriate way).

Conclusion

The Healthy Migrant Families Initiative developed in this project is evidence-based and grounded in cultural engagement principles. Implementation and evaluation using the same cultural engagement principles will further add to interventions to promote culturally competent obesity prevention strategies for African and other communities settling in Australia.

References

Food and Agriculture Organization, World Food Programme, International Fund for Agricultural Development. The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2012: Economic growth is necessary but not sufficient to accelerate reduction of hunger and malnutrition. Rome: FAO; 2012.

Saleh A, Amanatidis S, Samman S. The effect of migration on dietary intake, type 2 diabetes and obesity: the Ghanaian Health and Nutrition Analysis in Sydney, Australia (GHANAISA). Ecol Food Nutr. 2002;41:255–70.

Renzaho AMN. Migrants Getting Fat in Australia: Acculturation and its Effects on the Nutrition and Physical Activity of African Migrants to Developed Countries. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2007.

Rozman M. Ethiopian Community Diabetes Project report. Western Region Health Centre: Footscray; 2001.

Landman J, Cruickshank J. A review of ethnicity, health and nutrition-related diseases in relation to migration in the United Kingdom. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4(2B; SPI):647–58.

Renzaho A, Swinburn B, Burns C. Maintenance of traditional cultural orientation is associated with lower rates of obesity and sedentary behaviours among African migrant children to developed countries. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32(4):594–600.

Ayala GX, Baquero B, Klinger S. A systematic review of the relationship between acculturation and diet among Latinos in the United States: implications for future research. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(8):1330–44.

Delavari M, Sønderlund AL, Swinburn B, Mellor D, Renzaho A. Acculturation and obesity among migrant populations in high income countries–a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):458.

Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Hayes Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:367–97.

Rosas LG, Guendelman S, Harley K, Fernald LC, Neufeld L, Mejia F, et al. Factors associated with overweight and obesity among children of Mexican descent: results of a binational study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(1):169–80.

Ike-Chinaka C. Acculturation and childhood obesity among immigrant Nigerian children in northern California. Boston, MA: Paper presented at the 141st APHA Annual Meeting and Expo; 2013.

Coe K, Attakai A, Papenfuss M, Giuliano A, Martin L, Nuvayestewa L. Traditionalism and its relationship to disease risk and protective behaviors of women living on the Hopi reservation. Health Care Women Int. 2004;25(5):391–410.

Wang S, Quan J, Kanaya AM, Fernandez A. Asian Americans and obesity in California: A protective effect of biculturalism. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(2):276–83.

Cross T, Bazron B, Dennis K, Isaacs M. Towards a Culturally Competent System of Care, Volume I. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Child Development Center, CASSP Technical Assistance Center; 1989.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Cultural competency in health: A guide for policy, partnerships and participation. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2006.

Sawyer L, Regev H, Proctor S, Nelson M, Messias D, Barnes D, et al. Matching versus cultural competence in research: Methodological considerations. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18(6):557–67.

Gibbs L, Waters E, Renzaho A, Kulkens M. Moving towards increased cultural competency in public health research. In: Williamson A, DeSouza R, editors. Researching with Communities: Grounded Perspectives on Engaging Communities in Research. London: Muddy Creek Press; 2007.

Krasny M, Doyle R. Participatory approaches to program development and engaging youth in research: The case of an inter-generational urban community gardening program. J Ext. 2002;40(5):1–21.

Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–10.

Renzaho AMN. Challenges of negotiating obesity-related findings with African migrants in Australia: Lessons learnt from the African Migrant Capacity Building and Performance Appraisal Project. Nutr Diet. 2009;66:146–51.

Renzaho AMN, Green J, Mellor D, Swinburn B. Parenting, family functioning and lifestyle in a new culture: the case of African migrants in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Child Fam Soc Work. 2011;16:228–40.

Renzaho AMN, McCabe M, Sainsbury WJ. Parenting, rolereversals and the preservation of cultural values among Arabic speakingmigrant families in Melbourne, Australia. Int J Intercult Relat. 2010;35(4):416–24.

Mellor D, Renzaho A, Swinburn B, Green J, Richardson B. Aspects of parenting and family functioning associated with obesity in adolescent refugees and migrants from African backgrounds living in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2012;36(4):317–24.

Renzaho AM, McCabe M, Swinburn B. Intergenerational differences in food, physical activity, and body size perceptions among African migrants. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(6):740–54.

Halliday JA, Green J, Mellor D, Mutowo MP, de Courten M, Renzaho A. Developing programs for African families, by African families: Engaging African migrant families in Melbourne in health promotion interventions. Fam Community Health. 2013;37(1):60–73.

Renzaho A, Swinburn B, Mellor D, Green J, Lo SK. Obesity and its risk factors among African migrant adolescents: Assessing the role of intergenerational acculturation gap, family functioning, and parenting. Melbourne: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation; 2009.

Renzaho AMN, Gibbons K, Swinburn B, Jolley D, Burns C. Obesity and undernutrition in sub-Saharan African immigrant and refugee children in Victoria, Australia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006;15(4):482–90.

Simmons A, Mavoa H, Bell A, De Courten M, Schaaf D, Schultz J, et al. Creating community action plans for obesity prevention using the ANGELO (Analysis Grid for Elements Linked to Obesity) Framework. Health Promot Int. 2009;24(4):311–24.

Lee RM, Choe J, Kim G, Ngo V. Construction of the Asian American Family Conflicts Scale. J Couns Psychol. 2000;47(2):211.

Lau AS, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, Wood PA, Hough RL. The acculturation gap-distress hypothesis among high-risk Mexican American families. J Fam Psychol. 2005;19(3):367–75.

Van der Horst K, Kremers S, Ferreira I, Singh A, Oenema A, Brug J. Perceived parenting style and practices and the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages by adolescents. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(2):295–304.

Mellin AE, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Ireland M, Resnick MD. Unhealthy behaviors and psychosocial difficulties among overweight adolescents: the potential impact of familial factors. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(2):145–53.

Nowicka P, Pietrobelli A, Flodmark CE. Low‐intensity family therapy intervention is useful in a clinical setting to treat obese and extremely obese children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2007;2(4):211–7.

Rhee K. Childhood Overweight and the Relationship between Parent Behaviors, Parenting Style, and Family Functioning. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci. 2008;615(1):11–37.

Kothandan SK: School based interventions versus family based interventions in the treatment of childhood obesity- a systematic review. Archives of Public Health 2014, 72(3).

Willms JD. Vulnerable children and youth. Educ Can. 2002;42:40–3.

Kohen DE, Brooks-Gunn J, Leventhal T, Hertzman C. Neighborhood income and physical and social disorder in canada: Associations with young children’s competencies. Child Dev. 2002;73:1844–60.

Young KM, Northern JJ, Lister KM, Drummond JA, O’Brien WH. A meta-analysis of family-behavioral weight-loss treatments for children. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(2):240–9.

Kitzman-Ulrich H, Wilson DK, George SMS, Lawman H, Segal M, Fairchild A. The integration of a family systems approach for understanding youth obesity, physical activity, and dietary programs. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2010;13(3):231–53.

Golan M, Crow S. Targeting parents exclusively in the treatment of childhood obesity: Long-term results. Obes Res. 2004;12(2):357–61.

Winham DM. Culturally tailored foods and cardiovascular disease prevention. AJLM. 2009;3(1 suppl):64S–8S.

Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) (2008–0107) and the Australian Research Council (DP1094661). The authors thank the African Review Panel and steering committee members for guiding the project and African bilingual workers who helped with participant recruitment and data collecting in the pilot studies. We also thank the African community members who volunteered their time to participate in the pilot studies. Prof Andre Renzaho is supported by an ARC Future Fellowship (FT110100345).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

AR conceptualized and led all aspects of the study, as chief investigator of this ARC funded study (DP1094661) analysed the data and led the manuscript. JG contributed to the design and delivery of the obesity prevention program including review of the educational materials, design of culturally competent community forums with the target population. DM contributed to the design of the program, evaluated the study materials. All authors contributed to the development and revision of this manuscript. JH coordinated the program development process, development of the training and education materials, community consultation, recruitment and training of bilingual staff for the pilot studies. All authors reviewed drafts of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Renzaho, A.M., Halliday, J.A., Mellor, D. et al. The Healthy Migrant Families Initiative: development of a culturally competent obesity prevention intervention for African migrants. BMC Public Health 15, 272 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1628-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1628-2