Abstract

Background

Libya introduced rotavirus vaccine in October 2013. We examined pre-vaccine incidence of rotavirus hospitalizations and associated economic burden among children < 5 years in Libya to provide baseline data for future vaccine impact evaluations.

Methods

Prospective, hospital-based active surveillance for rotavirus was conducted at three public hospitals in two cities during August 2012 - April 2013. Clinical, demographic and estimated cost data were collected from children <5 hospitalized for diarrhea; stool specimens were tested for rotavirus with a commercial enzyme immunoassay. Annual rotavirus hospitalization incidence rate estimates included a conservative estimate based on the number of cases recorded during the nine months and an extrapolation to estimate 12 months incidence rate. National rotavirus disease and economic burden were estimated by extrapolating incidence and cost data to the national population of children aged <5 years.

Results

A total of 410 children <5 years of age with diarrhea were enrolled, of whom 239 (58%) tested positive rotavirus, yielding an incidence range of 418-557 rotavirus hospitalizations per 100,000 children <5 years of age. Most (86%) rotavirus cases were below two years of age with a distinct seasonal peak in winter (December-March) months. The total cost of treatment for each rotavirus patient was estimated at US$ 679 (range: 200–5,423). By extrapolation, we estimated 2,948 rotavirus hospitalizations occur each year in Libyan children <5 years of age, incurring total costs of US$ 2,001,662 (range: 1,931,726-2,094,005).

Conclusions

Rotavirus incurs substantial morbidity and economic burden in Libya, highlighting the potential value of vaccination of Libyan children against rotavirus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rotavirus is a major cause of severe diarrhea and hospitalization among children aged < 5 years worldwide. In 2008, globally rotavirus caused an estimated 453,000 deaths among children in this age group [1]; more than half of these deaths occurred in sub-Saharan Africa. In Libya, health service facilities in Libya are publicly owned and managed by the Ministry of Health. Public hospitals provide preventive and curative treatment to all citizens free of charge. While the Libyan government encourages the expansion of private health, private facilities have insufficient infrastructure to provide a full treatment service to severe diarrhea patients such as admission for intravenous fluid (IVF). Rotavirus disease accounted for 24 – 45% of diarrheal hospitalizations among children <5 during the period 1980-2009 [2,3]. The economic burden of rotavirus infections includes hospital costs, as well as indirect costs incurred by the society [4,5].

The World Health Organization (WHO) Strategic Advisory Committee on Immunization (SAGE) recommended adding rotavirus vaccine to all national immunization programmes, especially where the mortality rate of diarrhea affected up approximately 10% among children aged below 5 years [6-9]. Two live attenuated vaccines have been approved for global use: RotaTeq (RV5, Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) is a pentavalent (G1, G2, G3, G4, P[8]) human-bovine reassortant vaccine and Rotarix (RV1, GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium) is a monovalent (G1P[8]) vaccine derived from an attenuated human strain [10,11]. RotaTeq is administered at 2nd, 4th and 6th months of age, while Rotarix is administered at 2nd and 4th months of age. In 2009, the World Health Organization recommended the inclusion of rotavirus vaccine in the national immunization programs of all countries globally and particularly in those countries with high child mortality due to diarrhea [12]. In Libya, a live attenuated pentavalent vaccine based on a human rotavirus strain (RV5; RotaTeq™, Merck & Co. Inc., West Point, PA, USA) was introduced during October 1, 2013.

In February 2011, ongoing rotavirus surveillance activities in Libya were interrupted due to civil unrest. Our objective was to re-establish rotavirus surveillance to provide up-to-date estimates of the baseline pre-vaccine incidence of rotavirus hospitalizations among children aged < 5 years, and economic burden, in order to allow vaccine impact evaluations in the future.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted prospective, active, hospital-based surveillance for rotavirus-associated diarrheal hospitalizations among children < 5 years of age at three hospitals in two cities in Northwest Libya during the 9-month period from August 2012 to April 2013. These 3 hospitals are the only hospitals for treatment of severe diarrhea patients in the two cities, Khoms (estimated population 235,894) and Zliten (estimated population 239,860), which include a combined catchment population of 57,180 children aged < 5 years [13].

Surveillance and data collection

Children <5 years of age with diarrhea symptoms (three or more instances of liquid stool in a day) who sought therapy in the pediatric ward at the study hospitals were identified and parental/guardian consent was obtained. Trained nurses collected stool samples from the suspected patients, whereas the staff researcher collected the demographic, clinical and economic data from patient’s files. The stool samples were transferred to the national laboratory at the National Center for Diseases Control (NCDC) where an enzyme immunoassay (ProSpect Rotavirus Test, Oxoid Ltd, UK) was used to detect Group A rotavirus.

Treatment cost of hospitalized rotavirus patients was calculated from perspectives of hospital (direct cost) and patient (indirect cost). Hospital cost was conducted only in Zliten hospital because all studied hospitals are reimbursed by the same source, Ministry of health and covered closely similar population. Hospital cost included three components: bed-day (Per Diem), medication and laboratory investigation tests. The cost of bed-day in the hospital includes the cost of staff salaries and the hotel cost, consisting of furniture, foods, laundry, disposal, cleaning, operation and maintenance. The cost of bed-day was calculated by dividing annual expenditure at the pediatric ward (US$ 983,015) by the number of patient’s days in the pediatric ward (accounted at 8,470 patient days in 2012). The cost of bed-day in the pediatric ward was provided from the financial management at the Zliten hospital during 2012. Medication cost was obtained from the central pharmacy, which was calculated separately for each patient, and the cost of laboratory tests were provided by the main laboratory in the hospital.

Several cost elements from the patient perspective were obtained from parents, including 1) the transportation cost for trips to the hospital when bringing or visiting the admitted patient; 2) household cost of expenditures related to the treatment of hospitalized rotavirus patients such as hygiene items for baby such as diapers; and 3) lost income of caregivers during the patient’s illness.

Statistical analysis

We compared demographic and clinical characteristics of children hospitalized due to rotavirus diarrhea (stool tested positive for rotavirus) and diarrhea-hospitalizations not associated with rotavirus (tested negative for rotavirus). The annual incidence of rotavirus hospitalizations was calculated by dividing the number of rotavirus diarrhea hospitalizations by the number of children < 5 years of age residing in the catchment area of studies hospitals. We provided a conservative estimate calculated using the number of cases during the 9 months of enrolment as numerator (not inflating the number of rotavirus hospitalizations) to calculate annual incidence. Importantly, the historical months of the peak rotavirus season in Libya were captured during the 9 months of enrollment. Lastly, to estimate the annual number of rotavirus hospitalization countrywide and their associated costs, the conservative incidence and costs of rotavirus hospitalization from this study was extrapolated to the national population of 705,190 children <5 years of age in 2012 in Libya.

Data was analyzed by SPSS version 16. Chi-Square and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical tests were Chi-Square, X2 and t-test to obtain the outcomes such as mean, range and standard deviation. ANOVA or Mann–Whitney’s test were used to make a comparison between positive and negative-rotavirus cases. Mean, range and standard deviation were identified in economic data.

Ethics

University of Malaya Medical Ethics Committee (IRP - 908.6), NCDC in Libya, and study hospitals provided ethical clearance to conduct the study.

Results

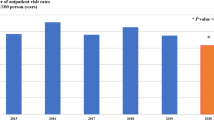

A total of 410 children hospitalized due to diarrhea were enrolled, of whom 239 (58%) tested positive for rotavirus. Based on the catchment population in the studied hospitals (57,180 children aged < 5 years) in 2012, the unadjusted (conservative) incidence rate of rotavirus associated with hospitalization in the studied hospitals during the study period (9 months) was 418 per 100,000 (95% confidence interval, 405-431 per 100,000, Table 1). Applying the conservative estimate for incidence rate to whole population of Libya (705,190 children aged <5 years) was yielded an estimate of 2,948 (95% confidence interval, 2,845-3,048) national hospitalized rotavirus patients associated with hospitalization in 2012. Most (86%) patients with rotavirus diarrhea patients were under two years of age (Figure 1) and the disease showed a distinct winter seasonal peak during the months from December to March (Figure 2). Compared with rotavirus-negative patients, those who were rotavirus-positive were significantly more likely to suffer severe dehydration and vomiting (Table 2). Median duration of hospitalization of rotavirus patients was 3 days (range 1-15) as compared with 2 days (range 1-13) among rotavirus negative patients (p = 0.05), and nearly all patients receive intravenous fluids. No deaths were reported.

Treatment costs

From the hospital perspective, the total expenditure to treat each rotavirus patient in the hospital was calculated to be US$ 488 (Intra quartile range [IQR], 318-541), the mean cost for each bed-day (Per Diem) was US$ 116 (Table 3), and the mean cost of medication was US$ 108 (IQR, 43-94). The most expensive medications were intravenous fluids and antibiotics which were given to 99% and 56% of rotavirus patients, respectively.

From the family perspective, the mean cost for each hospitalized patient was approximately US$ 191 (IQR, 74-220). Family costs combined with hospital costs yielded an overall cost to treat each rotavirus patient of US$ 679 (IQR, 476-737).

Overall, hospital costs comprised 72% of the total expenditure, and family cost made up 28%. Hospital cost included bed-day (51%), medication (16%) and laboratory investigations (5%). Considering the family cost, transportation, household costs, and lost incomes were 12%, 10% and 6% of total cost, respectively (Table 4).

National burden and costs of rotavirus hospitalization in Libya

Applying the conservative incidence rate for one year of surveillance yielded an estimate of 2,948 rotavirus hospitalizations annually in Libyan children <5 years of age. Combining these burden figures with cost data yielded a national economic burden of US$ 2,001,692 (range: 1,931,726-2,094,005).

Discussion

Our prospective, active, hospital-based surveillance for rotavirus shows that, prior to rotavirus vaccine introduction, 58% of diarrheal hospitalizations among children < 5 years of age in Northwest Libya were caused by rotavirus. Each rotavirus hospitalization incurred a total cost of US$ 679, of which 72% were costs of hospital expenditures. By extrapolation, we estimated that nearly 3000 hospitalizations for rotavirus diarrhea occur each year in Libyan children 5 years of age or 1 in 50 children born each year is hospitalized for rotavirus by age 5, incurring total costs of US$ 2,001,662. This tremendous morbidity and economic burden highlights the potential value of vaccination of Libyan children against rotavirus.

Reports from Libya during the period 1980-2009 showed a rotavirus detection rate of 24% to 45% among children <5 years of age hospitalized with diarrhea [2,3,14-19], which were slightly lower compared with our data. This difference may have resulted from not including 3 months in our study during which rotavirus rates are usually lower, thereby increasing the proportion of rotavirus cases among the studied population; however, the detection rate of rotavirus in our study is also similar to other regional countries such as Oman (70%) and Iran (58%) [2]. Characteristics of rotavirus infection such as vulnerable ages to the disease, season of increased infection, difference in gender (male and female) and places of residence (urban and rural areas) were also comparable to previous reports of rotavirus disease in Libya [3,14,17-19].

Previous studies have not assessed the economic burden of rotavirus hospitalizations in Libya. Hospital costs in this study represented 72% of total costs of disease, which was higher than that reported in the U.S (66%) [20], but lower than in Brazil (86%) [21]. Lost income of caretaker in Hong Kong represented 10% of monthly income [22], while it was about 7% in Libya. These data illustrate the substantial economic burden of rotavirus on both the health care system and families.

Our study has some limitations. Notably, we had planned to continue surveillance for collection of data for at least one full calendar year; however, due to the political and security situation after the Libyan revolution, the study was interrupted in April 2013. Since the 3 months of data that we were not able to capture were late spring/summer months with lower rotavirus prevalence in previous years [23]. Also, since we conducted surveillance in only 2 cities in Libya, our findings may not be representative of the entire population. Nevertheless, these are among two of the large cities in Libya and their population structure and composition is similar to the rest of the country.

Conclusion

We documented pre-vaccine incidence of rotavirus hospitalization in Libyan children and their associated costs to provide baseline data for future vaccine impact evaluations. Further studies of rotavirus disease burden among hospitalized children, in the form of active hospital based surveillance in Libya, will be crucial to understand the effect of introducing the vaccine into national childhood immunization, to provide scientific evidence for continued immunization efforts and identification of barriers for vaccine impact and effectiveness [24,25].

References

Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Steele AD, Duque J, the WHOcGRSN, et al. 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(2):136–41.

Hanane K, Isla O, El Khoury Antoine DY, Mireille G. Burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis in the Middle Eastern and North African pediatric population. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2009;11(1):9.

NCIDC, (National Center for Infectious disease Prevention and Control in Libya). Annual report for infectious disease in Libya. NCIDC: Surveillance department; 2009. p. 61–-64.

Gray J, Vesikari T, Damme V. Economic Burden of Rotavirus Disease. Health Protection Agency, London, UK, Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition: Centre for Infections; 2008.

WHO. Guidelines for estimating the economic burden of diarrhoeal disease with focus on assessing the costs of rotavirus diarrhoea. The Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals: WHO; 2005. p. 2–5.

Cortese MM, Parashar UD, Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis among infants and children: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Dept of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009;58:1–25.

WHO. Generic protocol for monitoring impact of rotavirus vaccination on gastroenteritis disease burden and viral strains. Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals.2008.

WHO. Rotavirus vaccines. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;51-52(84):533–40.

Patel MM, Steele D, Gentsch JR, Wecker J, Glass RI, Parashar UD. Real-world impact of rotavirus vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(1):S1.

CDC. Rotavirus vaccine. Atlanta: National Immunization Program, US Department of health and human service; 2010.

Rotavirus [http://www.immunizationinfo.org/vaccines/rotavirus]

WHO. Rotavirus vaccines:an update. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84(50):533–40.

General Authority for Information. Statistical Book. Tripoli, Libya: Libya Government; 2009.

Abugalia M, Cuevas L, Kirby A, Dove W, Nakagomi O, Nakagomi T, et al. Clinical features and molecular epidemiology of rotavirus and norovirus infections in Libyan children. J Med Virol. 2011;83(10):1849–56.

Ghenghesh KS, Franka EA, Tawil KA, Abeid S, Ali MB, Taher IA, et al. Infectious acute diarrhea in Libyan children: causative agents, clinical features, treatment and prevention. Libyan J Infect Dis. 2008;2:10Ö19.

Ghenghesh KS, Kreasta M, El-Bakoush M, Tobgi R. Rotaviruses-Associated gastroenteritis. Med J. 2002;2:12–7.

Kalaf RN, Elahmer OR, Zorgani AA, Ghenghesh KS. Rotavirus in children with diarrhea in Tripoli, Libya. Libyan J Med. 2011;6:10.

NCIDC, (National Center for Infectious disease Prevention and Control in Libya). Annual report for infectious disease in Libya. Surveillance department at NCIDC 2007;61-64.

NCIDC, (National Center for Infectious disease Prevention and Control in Libya). Annual report for infectious disease in Libya. Surveillance department at NCIDC 2008; 61-64.

Tucker AW, Haddix AC, Bresee JS, Holman RC, Parashar UD, Glass RI. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a rotavirus immunization program for the United States. JAMA. 1998;279(17):1371.

Constenla DO, Linhares AC, Rheingans RD, Antil LR, Waldman EA, da Silva LJ. Economic impact of a rotavirus vaccine in Brazil. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26(4):388.

Nelson EAS, Tam JS, Yu L-M, Ng Y-C, Bresee JS, Poon K-H, et al. Hospital-based study of the economic burden associated with rotavirus diarrhea in Hong Kong. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(Supplement 1):S64–70.

NCDC. Annual report for infectious disease in Libya. Surveillance department at NCDC 2007.

Patel MM, Patzi M, Pastor D, Nina A, Roca Y, Alvarez L, et al. Effectiveness of monovalent rotavirus vaccine in Bolivia: case-control study. BMJ. 2013;346:f3726.

Cortes JE, Curns AT, Tate JE, Cortese MM, Patel MM, Zhou F, et al. Rotavirus vaccine and health care utilization for diarrhea in U.S. children. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1108–17.

Acknowledgements

Authors appreciate the great help for the national laboratory at the NCDC, staffs at the hospitals. We are grateful to the parents who participated in the study. The study was supported by the University of Malaya/Ministry of Higher Education (UM/MOHE) High Impact Research Grant (E000010-20001), Malaysia, and also supported by the AADUN RP026-2012C grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SA and MD conceived the study and participated in its design. SA collected the data. SA, MD, EL and UP analyzed and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors interpreted the findings, and contributed to critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Alkoshi, S., Leshem, E., Parashar, U.D. et al. Anticipating rotavirus vaccines – a pre-vaccine assessment of incidence and economic burden of rotavirus hospitalizations among children < 5 year of age in Libya, 2012-13. BMC Public Health 15, 26 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1400-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1400-7