Abstract

Objectives

Transitions from middle adolescence into merging adulthood, a life stage between age 15–25, has a high prevalence of sleep problems. Mindfulness is a trait defined as being attentive to the present moment which positively relates to sleep quality. In this study, we aimed to investigate how resilience and emotional dysfunction may influence the relationship between trait mindfulness and sleep quality.

Methods

The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and Depression Anxiety Stress Scales were used to measure the key variables through an online survey of 497 participants between middle adolescence and emerging adults (317 females, mean age 18.27 ± 0.76 years). A process model was built to investigate the mediating roles of resilience and emotional dysfunction in the impact of trait mindfulness on sleep quality, together with the relationships between their specific components.

Results

We found a positive association between mindfulness and sleep quality through resilience and through emotional dysfunction, and through the sequential pathway from resilience to emotional dysfunction. Of note, acting with awareness (mindfulness facet) showed significant indirect effects on sleep quality, mediated by resilience and emotional dysfunction.

Conclusions

Our findings may unveil the underlying mechanisms of how low mindfulness induces poor sleep quality. The findings indicate that conceiving mindfulness as a multifaceted construct facilitates comprehension of its components, relationships with other variables, and underscores its potential clinical significance given its critical implications for mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Between middle adolescence to emerging adulthood is a pre-adult period between age 15 to 25 and during which individuals are considered immature when using cognitive, emotional, and behavioural measures comparing to adults [1,2,3]. Therefore, when sleep is suboptimal in timing or magnitude, middle adolescents and emerging adults are more vulnerable to psychiatric disorders comparing to adults [4]. Additionally, there is a high comorbidity between psychiatric disorders and sleep problems during the vulnerable phase of childhood and adolescence [5]. Using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), a prior study has revealed a high prevalence among emerging adults of insufficient sleep and poor sleep quality [6]. Emerging studies have indicated an underlying biological change in the circadian timing system and the homeostatic sleep regulatory process that might contribute to a sleep delay across pubertal development [3]. Also, individuals in this stage would face multiple external changes and developmental tasks in various domains (e.g., decreased parental supervision, competition in academy, intimate relationships), which may cause increased consumption of caffeine and night-use of electronics that could also delay bedtimes and risetimes. Maintaining sufficient sleep is paramount to the stable and healthy development of cognitive systems across later adolescence, especially to learning and memory [7].

Mindfulness has been described as being attentive to and aware of what is taking place at the present moment [8]. Individuals with higher mindfulness tend to focus on the present task or situation with little distraction. To date, more scholars have realized the association between trait mindfulness and sleep quality [9, 10]. Those with low mindfulness may suffer from many unwanted thoughts, thus causing a high-arousal state which significantly associates with insomnia, according to a metacognitive model of insomnia [11]. Lundh et al. (2005) also revealed that mindfulness may facilitate ‘cognitive deactivation’ which is similar to reducing arousal to mitigate sleep problems. A systematic review also provided substantial empirical evidence that mindfulness-based training may be beneficial to improving sleep quality [11].

Additionally, the sleep of adolescents and emerging adults has also been proposed to exert a negative modulatory influence on emotional regulation, which may intrigue the onset of psychiatric conditions especially anxiety and major depression [3]. Among undergraduate students, anxiety and depressive symptoms were most consistently associated with poorer sleep quality, as well as increased sleep latency, decreased sleep duration and sleep efficiency [12]. For local Chinese emerging adults, cultural differences exist such as early school time and heavy academic stress that may interact with the pubertal status to increase the risk of developing insomnia symptoms [13, 14]. Doorley et al. (2021) posited that mindfulness may be particularly effective in improving sleep quality by promoting acceptance in response to negative emotions (e.g., anxiety, stress, frustration) among individuals with chronic pain [15], which may also be particularly effective in middle adolescents and emerging adults.

Resilience was considered a strong underlying variable that affects the relationship between mindfulness and sleep quality in this study. Resilience has been described as a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity [16], which may play a preventive role in individuals with sleep disturbance among mid-adolescence and young adulthood [17, 18]. Resilience could mitigate the impairment of cognitive functions such as worries and ruminations [19], which might be an inducement to sleep disorders, according to Morin’s cognitive-behavioural model of insomnia [20]. Ong et al. (2012) suggested a specific metacognitive model of insomnia which proposed that the mindful attention state may allow individuals for more flexible responses toward sleep disturbance by disengaging from their daily concerns and strivings, which is constitutive of resilience. In conclusion, resilience may help adapt to the present situation, detach from unwanted thoughts and switch to normal sleep when individuals suffer from worries and ruminations in bed.

Emotional dysfunction was considered an underlying variable that affects the relationship between mindfulness and sleep quality. Emotional dysfunction is a negative psychological reaction to threats of personal life goals [21], which may have a profound negative effect particularly on the mental health of individuals between middle adolescence and emerging adulthood. According to an emotion regulation model, by changing attention deployment (resilience rather than rumination) and conducting cognitive re-appraisal (mindfulness and acceptance), emotional dysregulation would be alleviated when individuals are confronted with adversities [22, 23]. Prior studies have shown that maladaptive coping is a main predictor of emotional dysfunction and that resilience is a positive adaptation strategy which may help decrease the occurrence of negative emotions [24,25,26]. Yu et el. (2023) suggested a sequential mediating effect of emotional regulation and resilience on the relationship between the mindfulness component of self-compassion and college students’ depression [27]. In recent studies of somnipathy, low resilience and mood disturbance were remarkably positively correlated with sleep problems [28, 29]. Furthermore, emotional dysfunction (e.g., mood disorders including depression, anxiety, and stress) may play a vital mediating role in the association between low resilience and pre-sleep cognitive hyperarousal in subjects with insomnia [30].

Previous studies have led us to further investigations of the predetermined components of mindfulness, emotional dysfunction, and sleep quality. Sleep quality includes seven components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction [31]. Mindfulness was studied as a multidimensional construct, including observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging and non-reacting [32, 33]. Baer et al. (2006) also suggest that the examination of facets of mindfulness may unveil the nature of mindfulness and its relationships with other constructs [32]. Some research studied the correlations between specific facets of mindfulness and emotional dysfunction and suggested the most significant facets of non-judging and acting with awareness [34, 35]. Fong et al. (2020) found that acting with awareness and non-reacting could predict better sleep quality in the future. Apart from that, Sala et al. (2020) implied that the five facets of mindfulness have shown a strong association with health-promoting behaviours such as physical activity, healthy eating and sleep. It has been indicated that different subtypes of emotional dysfunction (i.e., depression, anxiety, stress) can be predicted by specific facets of mindfulness [36].

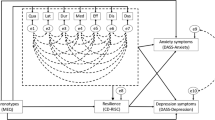

The purpose of the present study was to determine whether mindfulness was associated with sleep quality and to explore the mediating effects of two variables (resilience and emotional dysfunction) in this relationship among individuals from middle adolescents to emerging adults, through a conceptual model (Fig. 1). We hypothesized that mindfulness is positively associated with sleep quality, the relationship which may also establish between specific components of the two variables. Moreover, it is also speculated that trait mindfulness may exert its influence over sleep quality through emotional states and utility of resilience, based on a sequential mediation model.

Method

Participants

Data were randomly collected via public advertisement from a research project investigating the risk factors of poor sleep quality among Chinese individuals from middle adolescents to emerging adults. All students were recruited through a survey platform where they voluntarily signed up for the study. A total of 634 college students enrolled in the project. The inclusion criteria were (a) currently attending the first grade, (b) aging between 15 and 25, (c) agreeing to participate in the study, (d) signing an informed consent. We excluded students from 2nd, 3rd and 4th grades since they are highly occupied by job-seeking and preparation for the post-graduate entrance examination. Additionally, we excluded participants subjects with psychiatric disorders, a history of organic brain disorder, neurological disorders, mental retardation, cerebrovascular disease, alcohol or substance abuse, pregnancy, or any physical illness. To ensure data validity, 137 cases (21.6%) were excluded during data cleaning procedures: 75 responses were considered incomplete (missing values in all items of at least one key variable, n = 31, missing values in demographic variables, n = 44) and 62 participants provided invalid (e.g., 3 to 10 h) answers about recent bedtime.

Procedure

All materials and experimental procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the target university in Guangzhou, China. Participants completed the online questionnaires via the Wenjuanxing (Changsha Ranxing Information Technology Co., Ltd.) platform and received course credit for participation. Participants were also informed of the purpose, procedure, potential risks, confidentiality concerns, and remuneration of the project, as well as their right to withdraw from the project at anytime. Informed consent was obtained from all participants including parents of 45 minor participants. Participation was voluntary; writing summary papers on literature readings and participating in other studies were alternatives for students to obtain credits.

Measures

Mindfulness scale

Chinese version of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) was used in the present study, which has shown an acceptable psychometric property for the assessment of mindfulness [37]. This questionnaire evaluates five facets of mindfulness: observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging, and non-reacting. Observing refers to noticing or attending to external and internal stimuli. Describing means labelling experience with words. Acting with awareness refers to concentrating on the present situation without distraction. Non-judging refers to accepting, allowing or being nonevaluative to the present. Non-reacting refers to permitting inner thoughts and feeling to come and go without getting stuck in. Examples of items are “I intentionally stay aware of my feelings” and “I find myself doing things without paying attention”. All 39 items are measured by a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = very often. Participants with higher scores of FFMQ are considered to possess higher mindfulness in daily life. As a rule of thumb, values between 0.70 and 0.80 were regarded as acceptable, and > 0.8 as having good reliability [38]. The Chinese version of FFMQ was initially used in adults and had good reliability (Cronbach α = 0.83) [37]. For this study, the measure demonstrated acceptable reliability (Cronbach α = 0.77).

Resilience scale

The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) is a brief, self-rated measure of resilience [39]. A Chinese version of it has been validated [40], which comprises 25 items, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely). Those with higher scores reflect better resilience. The Chinese version of CD-RISC was initially used in adolescents and had good reliability (Cronbach α = 0.86) [40]. For this study, the measure demonstrated good reliability (Cronbach α = 0.93).

Emotional dysfunction scale

The Chinese version of the Depression Anxiety Stress (DASS-21) Scales [41, 42] was applied to assess the stress, depression and anxiety symptoms within a week. This questionnaire is rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 0 to 3. Participants with higher scores may have more serious emotional dysfunction. The Chinese version of DASS-21 was initially used in emerging adults and had good reliability (Cronbach α = 0.92, 0.92, and 0.93 for anxiety, depression, and stress subscales, respectively) [41]. For this study, the measures demonstrated acceptable to good reliability (Cronbach α = 0.74, 0.81, and 0.79 for anxiety, depression, and stress subscales, respectively).

Sleep scale

The PSQI is a 19-item self-rated questionnaire designed to measure seven domains to calculate component scores: subjective sleep quality (1 item), sleep latency (2 items), sleep duration (1 item), habitual sleep efficiency (3 items), sleep disturbances (9 items), use of sleeping medication (1 item), and daytime dysfunction (2 items) [43]. Each component has a score that ranges from 0 to 3. The scores of seven components will be summed to yield a PSQI global score ranging from 0 to 21; higher scores indicated poorer sleep quality. Examples of the questionnaire are “During the past month, when have you usually gone to bed at night?” and “During the past month, how often have you taken medicine (prescribed or “over the counter”) to help you sleep?”. A Chinese version of the scale was validated on adults [31]. The Chinese version of PSQI was initially used in adults and had good reliability (Cronbach α = 0.83) [31]. For this study, the measure demonstrated good reliability (Cronbach α = 0.77).

Statistical analyses

Data entry, management and descriptive statistics were performed using SPSS version 24.0. The descriptive analysis of the main variables was conducted and Pearson’s correlations were also calculated in order to explore the relationship among variables. Common-method variance was determined using Harman’s single-factor test. Next, the plug-in PROCESS and Model 6 were used to provide serial-multiple mediating model results. Firstly, mindfulness was entered as the independent variable, resilience and emotional dysfunction as the first and second mediator variables, and sleep quality as the outcome variable (see Fig. 1). Secondly, this was repeated with five mindfulness facets (observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging, non-reacting) as independent variables, resilience as the first mediator variable, three DASS subscales (depression, anxiety, stress) as the second mediator variables, and seven sleep quality components (i.e., subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction) as outcome variables. The 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (Cis) of direct and indirect effects were generated by bootstrapping with 5000 resamples [44]. The effects were regarded statistically significant if their Cis did not include 0.

Common method bias (CMB) test

Common method bias is normally prevalent in studies using self-administered questionnaires [45]. Measuring different constructions with similar scales format (e.g., Likert scales) can lead to spurious effects due to the measurement instruments rather than to the constructs being measured [46]. Harman’s single-factor test is one of the most widely used techniques to address the issue of common method bias [47]. Researchers load all the variables in their study into an exploratory factor analysis, and if a substantial amount of variance is present, either a single factor will emerge from the factor analysis or one general factor will account for the majority of the covariance [47].

Validation analyses

Some studies found the effects of gender on sleep quality, which may even cause differences in specific components of sleep [14, 48, 49]. Also, the wide disparity between urban and rural residences (including family income, body mass index (BMI) results) may affect sleep habits and health [50, 51]. Therefore, the results were reanalysed by regressing out gender, household registration, and age as co-variates in testing each model.

Results

Descriptive statistics

497 participants were eventually included, comprising 180 male and 317 female individuals between middle adolescence and emerging adulthood which ranged from 15 to 23 years old [mean = 18.28; standard deviation (SD) = 0.76, see Table 1]. Descriptive statistics (i.e., means and SDs) and bivariate correlations of the key variables are presented in Table 2. As expected, results showed a positive correlation between mindfulness and sleep quality. Additionally, we also found that mindfulness was positively associated with resilience and negatively associated with emotional dysfunction. Further, resilience was negatively associated with emotional dysfunction and positively associated with sleep quality (ps<0.05). The correlation between emotional dysfunction and sleep quality was negative.

Common method bias (CMB) test

The analysis yielded 12 factors with eigenvalue greater than 1, and the variation explained by the first one was 18.27%, which did not exceed the critical standard of 40% [47]. Moreover, these 12 factors explained 61.42% of the total variation, which was acceptable owning to more than the minimum criteria of 50% [52]. Therefore, it suggested that CMB did not pose a serious threat to interpreting our present study.

Influence of trait mindfulness on sleep quality

Standardized effects between variables are presented in Fig. 2. This study found a positive effect of mindfulness on sleep quality (total effect: B = -0.263, SE = 0.043, 95% CI = [-0.348, -0.177], p < 0.001). However, when resilience and emotional dysfunction were included in the analysis, this coefficient was not statistically significant (direct effect: B = -0.004, SE = 0.053, 95% CI = [-0.108, 0.100], p = 0.943). Mindfulness was found associated with resilience (B = 0.631, SE = 0.035, 95% CI = [0.563, 0.700], p < 0.001) and emotional dysfunction (B = -0.227, SE = 0.049, p < 0.001).

Effects of each path in the mediation model were listed in Table 3. The present study found a significant indirect effect of mindfulness →resilience →sleep quality (B = -0.089, SE = 0.036, 95% CI = [-0.162, -0.023]). In addition, the indirect effect of mindfulness →emotional dysfunction →sleep quality was also significant (B = -0.083, SE = 0.019, 95% CI = [-0.123, -0.047]). Finally, the study indicated a remarkable indirect effect of mindfulness →resilience →emotional dysfunction →sleep quality (B = -0.086, SE = 0.020, 95% CI = [-0.127, -0.051]). The ratio of total indirect effect and three branches of indirect effects to total effect were 96.1%, 33.4% (mindfulness →resilience →sleep quality), 30.9% (mindfulness →emotional dysfunction →sleep quality) and 31.8% (mindfulness →resilience →emotional dysfunction →sleep quality), respectively.

The specific direct and indirect effects of each facet of trait mindfulness on components of sleep quality were displayed in Fig. 3. Among multiple mediation models, acting with awareness (mindfulness facet) showed a significant indirect effect on subjective sleep quality and daytime dysfunction (sleep quality components) through resilience and through emotional dysfunction (depression, anxiety and stress, respectively). Furthermore, acting with awareness also had an indirect effect on these two sleep quality components through resilience and emotional dysfunction (i.e., depression, anxiety and stress) in sequence (see Table S1 in the supplementary). The indirect effects of acting with awareness on the other five sleep quality components (sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, or use of sleeping medication) were not significant. There is no association between acting with awareness and habitual sleep efficiency, use of medication. Resilience and emotional dysfunction did not mediate the association between acting with awareness and sleep latency, sleep duration. Resilience did not mediate the association between acting with awareness and sleep disturbance.

Acting with awareness (mindfulness facet) showed significant indirect effect on subjective sleep quality and daytime dysfunction (sleep quality components) through resilience and emotional dysfunction (depression, anxiety and stress, respectively). Paths and path coefficients (standardized) of sequential mediation models. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Validation analyses

The findings remained even after the exclusion of co-variates (i.e., gender, household registration and age) (see Figure S1 and Figure S2 in the supplementary). Each path only changes numerically, while the significance remains unchanged.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the roles of resilience and emotional dysfunction in the impact of trait mindfulness on sleep quality among individuals between middle adolescence and emerging adulthood. Although the association between trait mindfulness and sleep quality has been noted by previous studies [10, 53, 54], the underlying mechanisms remain largely unclear among individuals between middle adolescence and emerging adulthood who have a high prevalence of poor sleep quality [6]. The present study tested whether trait mindfulness would associate with sleep quality through the modulation of resilience and emotional dysfunction. Importantly, the results demonstrated that the impact of trait mindfulness on sleep quality may be mediated by resilience and emotional dysfunction, after controlling for gender and household registration type. In other words, trait mindfulness was related to high resilience, and in turn, high resilience predicted positive emotion, and positive emotion may attenuate sleep problems. Apart from that, we further explored the associations between mindfulness facets and sleep quality components through the mediation models. Mindfulness facet of acting with awareness and sleep components of subjective sleep quality and daytime dysfunction were found significant in the mediation models. That is, acting with awareness related to high resilience, high resilience was associated with less emotional dysfunction, and thus improving subjective sleep quality as well as daytime dysfunction.

Mindfulness relates to sleep quality positively

Mindfulness has long been regarded as relating to mental health, possibly for its engagement in attentional control and emotional regulation [55]. Therefore, it is plausible that this psychological process is rather critical for those who suffer from emotional difficulties [14]. Additionally, mindfulness may equip emerging adults with a sense of self-control towards their lives [56]. Encouraging mindfulness in cognitive control and emotion regulation could be applied to emerging adults, which may contribute to mitigating the occurrence of sleep disorders [9, 10, 57]. Indeed, emerging adulthood is a transition period into an adult role [58], during which it might be painful for emerging adults to encounter the ambiguity of being an adult. Therefore, the possibility of the onset and escalation of psychological disorders such as major depression and anxiety disorder increases across puberty maturation [59]. The results offer implications for future research concerning the facets of mindfulness in relation to mental well-being.

The current study extended the literature on the benefits of mindfulness on mental well-being [36, 60, 61]. There were five facets of mindfulness (observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging, and non-reacting) among which acting with awareness was confirmed significant in the present study, consistent with former research [34, 35, 57]. Acting with awareness has been described as the central defining core of mindfulness, which may facilitate attention to one’s needs, values, and interests, making one more likely to regulate behaviour that leads to psychological well-being [8]. Emerging adults with their own initiatives to deal with various difficulties may have a sense of self-control and domination towards themselves. Therefore, they may believe in themselves to overcome sleep difficulties, by trying to detach from rather than surrender to various triggers of sleep problems. Higher resilience may enable them to detach from unwanted or intrusive thoughts and switch back to sleep mode in a shorter time [19]. Prior mentioned, there were seven components of PSQI (subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction) among which the components of subjective sleep quality and daytime dysfunction were found significant in mediation models, respectively. It has also been postulated that resilience and daytime dysfunction could influence each other in the long term which shares a similar mechanism of modulating human’s brain [62, 63].

The mediating role of resilience

Together with the findings that resilience has direct effects on the occurrence of sleep quality, our findings proposed a potential intervention for emerging adults that is shown to evolve stronger mindfulness. Such an intervention would be prospective in strengthening the ability to overcome sleep problems by raising individual resilience, suggested by Morin’s cognitive-behavioural model [20]. Another research indicated that trait mindfulness may promote resilience by suppressing unrelated information or provoking physiological arousal [61], which may result in fewer sleep disturbances [64, 65].

The mediating role of emotional dysfunction

The second sequential indirect path was mindfulness negatively associated with emotional dysfunction, while the latter was negatively associated with sleep quality, which mainly consists with prior studies [10, 66]. Mindfulness is deemed as an approach to emotion regulation [67], for individuals with higher levels of mindfulness may have better skills in coping with emotional dysfunction [68]. A study provided longitudinal evidence that mindfulness facet of acting with awareness could significantly predict sleep quality through emotional distress among Chinese cancer patients [69]. Although mindfulness facets of observing and non-reacting indicated a significant link with sleep quality through psychological distress [70], none of such results were detected in the present study. Additionally, some studies have observed that individuals with emotional dysfunction were at a higher risk of sleep dysfunction [71,72,73]. For instance, social anxiety has been implied associated with specific sleep problems of sleep latency, sleep disturbance, and daytime sleep dysfunction [74]. A potential explanation is that individuals with stress, anxiety or depression are less likely to use adaptive coping strategies, leading to a worsening of sleep quality [75].

Resilience and emotional dysfunction

The third sequential path was mindfulness positively connected with resilience, then resilience negatively associated with emotional dysfunction, and the latter negatively correlated with sleep quality. Resilience has been confirmed negatively linked to emotional dysfunction according to previous studies [26, 76], possibly explained by that individuals with higher resilience may have stronger problem-solving skills and thus reducing multiple triggers of emotional dysfunction [77]. Apart from that, a longitudinal study indicated that resilience may foster perceived competence and self-confidence [78] which could help encourage individuals to overcome difficulties that may cause emotional distresses.

Limitations

The current study should be interpreted with caution owing to some existing limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional design nature of the present study may preclude the exploration of causal correlations among variables. Some relations identified in the current study may be bi-directional or there are additional factors which could mediate or moderate the relationships. For example, neuroticism has been found to moderate the impact of mindfulness on sleep quality in college students [10]. Hence, our findings should be further verified by more longitudinal studies with better control of underlying contributing factors. Secondly, due to potential introduced recall bias, the self-reported approach may limit the validity of the results [47]. Thirdly, the study sample only represented emerging adults from a single university and the results may therefore be unable to generalize to a larger emerging adults population. Future studies involving multiplex samples from varied universities are required. Fourthly, the non-probability sampling methods (self-selection sampling) and volunteer bias (i.e., individuals who have trouble in sleep may be more prone to participate) may undermine the external validity. Therefore, more probability-sampling studies with smaller biases should further inspect the study. Fifthly, we did not include BMI and family income as covariates, which may be cofounders in the study. Scholars indicated that low-income families mainly concentrate in rural areas for natural, geographical, and policy reasons [79, 80]. A study found that the prevalence of obesity is significant between urban and rural residences [81]. Additionally, there is a certain extent of misreporting of BMI [82]. Results may be inaccurate for BMI and family income covariates, though we simplified the BMI and family income to urban-rural disparity for humanistic care and accurate collection.

Conclusions

Individuals between middle adolescence and emerging adulthood with higher trait mindfulness may have better sleep quality, while resilience and emotional dysfunctions play mediating roles between them. Moreover, individuals between middle adolescence and emerging adulthood with better acting with awareness (facet of mindfulness) may have better subjective sleep quality and less daytime dysfunction through resilience and emotional dysfunction. To improve sleep quality, it is suggested that future research would focus on the use of mindfulness training in sleep improvement, especially through strengthening resilience and reducing emotional dysfunction.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–80.

Hochberg ZE, Konner M. Emerging Adulthood, a Pre-adult Life-History Stage. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:918.

Tarokh L, Saletin JM, Carskadon MA. Sleep in adolescence: physiology, cognition and mental health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;70:182–8.

Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(12):947–57.

Tesler N, Gerstenberg M, Huber R. Developmental changes in sleep and their relationships to psychiatric illnesses. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(6):572–9.

Becker SP, et al. Sleep in a large, multi-university sample of college students: sleep problem prevalence, sex differences, and mental health correlates. Sleep Health. 2018;4(2):174–81.

Knoop MS, de Groot ER, Dudink J. Current ideas about the roles of rapid eye movement and non-rapid eye movement sleep in brain development. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110(1):36–44.

Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–48.

Fang Y, et al. Conditional effects of mindfulness on sleep quality among clinical nurses: the moderating roles of extraversion and neuroticism. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24(4):481–92.

Ding X, et al. Relationship between Trait Mindfulness and Sleep Quality in College students: a conditional process model. Front Psychol. 2020;11:576319.

Ong JC, Moore C. What do we really know about mindfulness and sleep health? Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;34:18–22.

Niu X, Snyder HR. The role of maladaptive emotion regulation in the bidirectional relation between sleep and depression in college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2023;36(1):83–96.

Liu X, et al. Sleep patterns and sleep problems among schoolchildren in the United States and China. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1 Suppl):241–9.

Zhang J, et al. Emergence of sex differences in insomnia symptoms in adolescents: a Large-Scale School-Based study. Sleep. 2016;39(8):1563–70.

Doorley J, et al. The role of mindfulness and relaxation in improved sleep quality following a mind-body and activity program for chronic pain. Mindfulness (N Y). 2021;12(11):2672–80.

Robertson HD, et al. Resilience of primary healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(647):e423–33.

Brand S, et al. During early and mid-adolescence, greater mental toughness is related to increased sleep quality and quality of life. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(6):905–15.

Notario-Pacheco B, et al. Reliability and validity of the spanish version of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (10-item CD-RISC) in young adults. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes. 2011;9(1):63–3.

Hoorelbeke K, et al. Between vulnerability and resilience: a network analysis of fluctuations in cognitive risk and protective factors following remission from depression. Behav Res Ther. 2019;116:1–9.

Morin CM. Insomnia: Psychological Assessment and Management. 1993.

Faessler L, et al. Psychological distress in medical patients seeking ED care for somatic reasons: results of a systematic literature review. Emerg Med J. 2016;33(8):581–7.

McRae K, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation. Emotion. 2020;20(1):1–9.

Matud MP et al. Stress and psychological distress in emerging Adulthood: a gender analysis. J Clin Med, 2020. 9(9).

Mahmoud JS, et al. The relationship among young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33(3):149–56.

Anyan F, Hjemdal O. Adolescent stress and symptoms of anxiety and depression: Resilience explains and differentiates the relationships. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:213–20.

Shin YC, et al. Resilience as a protective factor for depressive Mood and anxiety among korean employees. J Korean Med Sci. 2019;34(27):e188.

Yu S, Zhang C, Xu W. Self-compassion and depression in chinese undergraduates with left-behind experience: mediation by emotion regulation and resilience. J Clin Psychol. 2023;79(1):168–85.

Cheng MY, et al. Relationship between resilience and insomnia among the middle-aged and elderly: mediating role of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies. Psychol Health Med. 2020;25(10):1266–77.

Wong HY et al. Relationships between Severity of Internet Gaming Disorder, Severity of Problematic Social Media Use, Sleep Quality and Psychological Distress. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020. 17(6).

Palagini L, et al. Lack of resilience is related to stress-related sleep reactivity, Hyperarousal, and emotion dysregulation in Insomnia Disorder. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(5):759–66.

Tsai PS, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) in primary insomnia and control subjects. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(8):1943–52.

Baer RA, et al. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45.

Cardaciotto L, et al. The assessment of present-moment awareness and acceptance: the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale. Assessment. 2008;15(2):204–23.

Fino E, Martoni M, Russo PM. Specific mindfulness traits protect against negative effects of trait anxiety on medical student wellbeing during high-pressure periods. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021;26(3):1095–111.

Carpenter JK, et al. The relationship between trait mindfulness and affective symptoms: a meta-analysis of the five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;74:101785.

Soysa CK, Wilcomb CJ. Mindfulness, Self-compassion, Self-efficacy, and gender as predictors of Depression, anxiety, stress, and well-being. Mindfulness. 2015;6(2):217–26.

Hou J, et al. Validation of a chinese version of the five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in Hong Kong and development of a short form. Assessment. 2014;21(3):363–71.

Cicchetti D. Guidelines, Criteria, and rules of Thumb for evaluating normed and standardized Assessment Instrument in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6:284–90.

Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82.

Fu C, Leoutsakos JM, Underwood C. An examination of resilience cross-culturally in child and adolescent survivors of the 2008 China earthquake using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). J Affect Disord. 2014;155:149–53.

Chan RC, et al. Extending the utility of the Depression anxiety stress scale by examining its psychometric properties in chinese settings. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2–3):879–83.

Lovibond PF, Lovibond SHJBR, Therapy. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and anxiety inventories. 1995. 33(3): p. 335–43.

Buysse DJ et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research 1989. 28(2): p. 193–213.

Hayes AF, Rockwood NJ. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav Res Ther. 2017;98:39–57.

Kock F, Berbekova A, Assaf AG. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: detection, prevention and control. Tour Manag. 2021;86:104330.

Kamakura W. Common Methods Bias. 2010.

Podsakoff PM, et al. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903.

Mong JA, Cusmano DM. Sex differences in sleep: impact of biological sex and sex steroids. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016;371(1688):20150110.

Franco P, et al. Sleep during development: sex and gender differences. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;51:101276.

Rae DE, et al. Sleep and BMI in south african urban and rural, high and low-income preschool children. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):571.

Tomaz SA et al. Screen time and sleep of Rural and Urban South African Preschool Children. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020. 17(15).

Beavers AS, et al. Practical considerations for using exploratory factor analysis in Educational Research. Volume 18. Practical Assessment Research & Evaluation; 2013. p. 13.

Garland SN, et al. Dispositional mindfulness, insomnia, sleep quality and dysfunctional sleep beliefs in post-treatment cancer patients. Pers Indiv Differ. 2013;55(3):306–11.

Bogusch LM, Fekete EM, Skinta MD. Anxiety and depressive symptoms as mediators of Trait Mindfulness and Sleep Quality in emerging adults. Mindfulness. 2016;7(4):962–70.

Schuman-Olivier Z, et al. Mindfulness and Behavior Change. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2020;28(6):371–94.

Bowlin SL, Baer RA. Relationships between mindfulness, self-control, and psychological functioning. Pers Indiv Differ. 2012;52(3):411–5.

Sala M, et al. Trait mindfulness and health behaviours: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2020;14(3):345–93.

Arnett JJ, Žukauskienė R, Sugimura K. The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(7):569–76.

Schulenberg JE, Sameroff AJ, Cicchetti D. The transition to adulthood as a critical juncture in the course of psychopathology and mental health. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16(4):799–806.

Shankland R, et al. Improving Mental Health and Well-Being through Informal Mindfulness Practices: an intervention study. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2021;13(1):63–83.

MacAulay RK et al. Trait mindfulness associations with executive function and well-being in older adults. Aging Ment Health, 2021: p. 1–8.

Wang J, et al. Exploring the bi-directional relationship between sleep and resilience in adolescence. Sleep Med. 2020;73:63–9.

Maier SF, Watkins LR. Role of the medial prefrontal cortex in coping and resilience. Brain Res. 2010;1355:52–60.

Miller MB, et al. Longitudinal Associations between Sleep, intrusive thoughts, and alcohol problems among veterans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43(11):2438–45.

Sella E, Borella E. Strategies for controlling sleep-related intrusive thoughts, and subjective and objective sleep quality: how self-reported poor and good sleepers differ. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25(10):1959–66.

Park M, et al. Mindfulness is associated with sleep quality among patients with fibromyalgia. Int J Rheum Dis. 2020;23(3):294–301.

Finkelstein-Fox L, Park CL, Riley KE. Mindfulness and emotion regulation: promoting well-being during the transition to college. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2018;31(6):639–53.

Vilaverde RF, Correia AI, Lima CF. Higher trait mindfulness is associated with empathy but not with emotion recognition abilities. R Soc Open Sci. 2020;7(8):192077.

Fong TCT, Ho RTH. Mindfulness facets predict quality of life and sleep disturbance via physical and emotional distresses in chinese cancer patients: a moderated mediation analysis. Psychooncology. 2020;29(5):894–901.

Lau WKW, et al. Potential mechanisms of mindfulness in improving sleep and distress. Mindfulness (N Y). 2018;9(2):547–55.

Guo L, et al. Prevalence and correlates of sleep disturbance and depressive symptoms among chinese adolescents: a cross-sectional survey study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(7):e005517.

Xu Z, et al. Sleep quality of chinese adolescents: distribution and its associated factors. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012;48(2):138–45.

Byars KC, Yeomans-Maldonado G, Noll JG. Parental functioning and pediatric sleep disturbance: an examination of factors associated with parenting stress in children clinically referred for evaluation of insomnia. Sleep Med. 2011;12(9):898–905.

Cavalcanti L, et al. Constructs of poor sleep quality in adolescents: associated factors. Cad Saude Publica. 2021;37(8):e00207420.

Tavernier R, Willoughby T. Are all evening-types doomed? Latent class analyses of perceived morningness-eveningness, sleep and psychosocial functioning among emerging adults. Chronobiol Int. 2014;31(2):232–42.

González-Hernández J et al. Resilient resources in youth athletes and their relationship with anxiety in different Team Sports. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020. 17(15).

Ertekin Pinar S, Yildirim G, Sayin N. Investigating the psychological resilience, self-confidence and problem-solving skills of midwife candidates. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;64:144–9.

Orkaizagirre-Gómara A, et al. Testing general self-efficacy, perceived competence, resilience, and stress among nursing students: an integrator evaluation. Nurs Health Sci. 2020;22(3):529–38.

Liu Y, Xu Y. A geographic identification of multidimensional poverty in rural China under the framework of sustainable livelihoods analysis. Appl Geogr. 2016;73:62–76.

Liu Y, Liu J, Zhou Y. Spatio-temporal patterns of rural poverty in China and targeted poverty alleviation strategies. J Rural Stud. 2017;52:66–75.

Hu L, et al. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, abdominal obesity and obesity-related risk factors in southern China. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0183934.

Flegal KM, et al. Comparisons of self-reported and measured height and weight, BMI, and obesity prevalence from national surveys: 1999–2016. Obes (Silver Spring). 2019;27(10):1711–9.

Acknowledgements

We want to express our gratitude to all participants in the present study.

Funding

The work has been supported by the National Key R & D Program of China (SIT2030-Major Projects 2022ZD0214300), Nature Science Foundation of China (31900806, 32271139), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (ref: 2023A1515011331), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (ref: 2023A04J1964), Guangzhou Philosophy and Social Science Project for 2022 Yangcheng Scholar during the fourteenth Five-year Plan Period (ref: 2022GZQN30). The funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, and analysis, interpretation of the data, preparation, and approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RZ and HZ devised the concept and supervised the study. RZ contributed to experimental programming and data collection. HZ and ZZ contributed to data analysis and interpretation of data. HZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. ZZ, XF and RZ revised and improved the manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Southern Medical University. Participants completed the online questionnaires in Wenjuanxing (Changsha Ranxing Science and Technology) and received course credit for participation. Participants were also informed of the purpose, procedure, potential risks, confidentiality concerns, and remuneration of the project, as well as their right to withdraw from the project anytime. All participants gave informed consent to participate in the study, and the informed consent of the participants under the age of 16 were obtained from their parents or guardians. Participation was voluntary; writing summary papers on literature readings and participating in other studies were alternatives for students to obtain credits.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

: Table S1, Figures S1 and S2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, H., Zhu, Z., Feng, X. et al. Low mindfulness is related to poor sleep quality from middle adolescents to emerging adults: a process model involving resilience and emotional dysfunction. BMC Psychiatry 23, 626 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05092-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05092-1