Abstract

Background

Depression and anxiety symptoms are two common psychological disturbances in cervical cancer patients. We tested whether sense of coherence (SOC) mediates the association of perceived social support (PSS) with depression and anxiety symptoms among cervical cancer patients in China.

Methods

We conducted a survey involving 294 cervical cancer patients aged ≥ 18 years from July to December 2020 at three hospitals in Liaoning Province, China; 269 patients completed the survey. We included a demographic questionnaire, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), Antonovsky’s Sense of Coherence Scale, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, and the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) in this study. We used hierarchical regression analysis to examine the relationship among PSS, SOC, and symptoms of depression and anxiety. We used asymptotic and resampling strategies to explore the mediating effect of SOC.

Results

PSS was negatively associated with depressive symptoms (r = − 0.439, P < 0.01) and anxiety symptoms (r = − 0.325, P < 0.01). SOC was negatively related to depressive symptoms (r = − 0.627, P < 0.01) and anxiety symptoms (r = − 0.411, P < 0.01). SOC partially mediated the association between PSS and depressive symptoms (a*b = − 0.23, BCa95% CI: [− 0.31, − 0.14]) and anxiety symptoms (a*b = − 0.15, BCa95% CI: [− 0.23, − 0.08]). The proportions of the mediating effect accounting for SOC were 49.78% and 41.73% for depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms, respectively.

Conclusion

The study showed that SOC could mediate the association between PSS and symptoms of depression and anxiety. This suggests that SOC might serve as a potential target for intervention in symptoms of depression and anxiety that accompany cervical cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the most common female gynecologic cancer. In 2020, 604,127 newly diagnosed cases and 341,831 deaths were reported globally [1]. In China, the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer are gradually increasing, and cervical cancer tends to occur in younger women [2]. Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide, with an estimated 14,000 new cases and 4,000 cervical cancer-related deaths in the United States in 2022 [3]. Resection is a predominant and effective method of treatment for cervical cancer, after which adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy is sometimes required according to the patient’s tumor burden [4,5,6]. However, these treatments are often accompanied by unavoidable physical problems such as poor sexual function and surgical trauma, as well as great psychological worries such as self-blame and fear of disease recurrence, which could lead to distress, discomfort, and anxiety in and worse postoperative experiences for cervical cancer patients [7, 8]. Therefore, a large number of cervical cancer patients suffer from anxiety and depression, leading to a decline in their quality of life [8]. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to improving the mental health of patients after cervical cancer surgery.

Some studies have shown that depression and anxiety are two common psychological disorders in cancer patients [9]. Our previous meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of depression (54.90% vs. 17.50%) and anxiety (49.69% vs. 18.37%) was significantly higher in Chinese cancer patients than in noncancer patients [10]. Among gynecological cancer patients, cervical cancer patients had the worst emotional distress and quality of life scores [11,12,13,14]. A longitudinal study showed that the prevalence of depression and anxiety in cervical cancer patients at baseline ranged from 7.4 to 11.4% and 53.4–62.9%, respectively [15]. Many studies have focused on variables that influence depression and anxiety in cancer patients because of the high prevalence and negative effects of depression and anxiety symptoms. In addition to the influence of demographic and clinical variables on depression and anxiety, positive psychological factors have begun to receive increasing attention in cancer research in the past 20 years [15, 16]. Based on the literature review, we found that variables such as perceived social support (PSS) and sense of coherence (SOC) were key research topics in this field [22, 28].

In general, “social support” refers to help and protection given to others, especially on an individual basis. One of the most effective means of coping with challenging life events is PSS, which determines a person’s health and well-being [17, 18].

The main effect model theory of social support [19] indicates that social support has a general beneficial effect. Regardless of whether an individual is facing a stressful situation, a good social support system has a positive effect on their mental health. In the main effect model, social support acts on individual mental health in two ways. One way is by providing sufficient material, sufficient information, scientific lifestyle information, correct behavior information, etc., as external resources to directly maintain individual physical and mental health. Some studies have shown that social support has negative correlations with depressive and anxiety symptoms [20,21,22]. Having a good social support system can prevent depressive and anxiety symptoms. Fisher et al. [23, 24] concluded that social support was strongly associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with breast cancer and ovarian cancer. They indicated that to help patients reduce the risk of developing depressive and anxiety symptoms, optimizing the social support level might be a good intervention method. In turn, depressive and anxiety symptoms may affect social support. A study suggested that the relationship between PSS and depression was bidirectional [25]. Moreover, some studies have indicated that social support correlates with recovery from depressive and anxiety symptoms [26,27,28].

The other way that health is influenced in the main effect model of social support is by meeting an individual’s psychological needs, preserving enough positive psychological capital, and maintaining mental health indirectly through improving internal resources [31, 32]. SOC is a core concept of the salutogenic model of health. It reflects an individual’s general perception and his or her internal feelings, which involves inner stability and confidence [34]. We propose that sense of coherence is a mediator of the effects of social support on depressive and anxiety symptoms based on the concept of positive psychology [29, 30, 33], which refers to an individual’s ability to adapt positively to the environment when coping with negative events such as trauma and to mobilize psychological resources to face stress with a positive coping attitude, thus reducing negative effects. Many factors influence SOC, including social support. Previous studies have revealed that perceived social support is positively associated with the sense of coherence [35,36,37,38]. Some longitudinal studies have supported this finding [39,40,41]. In a one-year prospective study, Skärsäter et al. found that PSS is an important cornerstone in the restoration of a person’s SOC. It can be used in interventions that include a patient’s family or close social network in combination with support to assist the patient in improving their SOC [39]. A longitudinal study of people with mental health problems indicated that improving social support with a special emphasis on opportunities for nurturance might provide important contributions for increasing the sense of coherence [40]. Moreover, a five-year follow-up study indicated that PSS appears to be an important component of SOC changes among residents of nursing homes (NH) [41]. Some studies showed that offering greater support to people may substantially strengthen their sense of coherence [35, 38].

It has also been well documented that sense of coherence is often negatively correlated with depressive and anxiety symptoms [42, 43]. Even minor levels of depression are related to weaker SOC [41, 44]. Higher SOC is associated with higher mental health, higher affective well-being, and lower depression levels. In the past few years, with the development of positive psychology, many academics have begun to pay attention to positive psychological changes in individuals after experiencing traumatic events [33]. SOC could act as a positive coping resource for cancer patients with depression [45]. People with a higher level of SOC have reported fewer mental symptoms, such as anxiety and depression, and the prevalence of depression in this group is significantly reduced [46]. Because social support can improve SOC and SOC could act as a positive coping resource for cancer patients with depression [45], SOC may play a mediating role in the relationship between social support and depressive and anxiety symptoms. SOC has also been proposed as a mediator in the relationship between perceived stress and depression in breast cancer patients [47], and Pasricha et al. [48] found that the relationship between perceived social support and mental health was mediated by sense of coherence, which further suggested that SOC may play a mediating role in gynecological cancer patients.

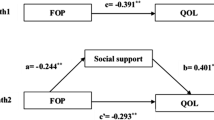

Judging from the literature, the current domestic research tends to analyze the relationship among PSS, SOC, and symptoms of depression and anxiety in a single visual way. Few studies have comprehensively explored the relationship among these three variables in cervical cancer patients. On the other hand, previous studies were limited to negative outcomes such as symptoms of depression and anxiety. They ignored the large and sustainable impact of positive psychological resources on negative outcomes. Under this background, we hypothesized that SOC would mediate the relationship between PSS and symptoms of depression and anxiety in cervical cancer patients, as shown in Fig. 1.

Theoretical model of the mediating role of sense of coherence (SOC) in the relationship between perceived social support (PSS) and depressive and anxiety symptoms. (a) The associations of PSS and SOC; (b) the correlation of SOC with depressive and anxiety symptoms after controlling for the predictor variable; (c) the correlation of PSS with depressive and anxiety symptoms; (c’) the correlation between PSS and depressive and anxiety symptoms after adding SOC

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

The study protocol was in accordance with ethical standards and approved by the Ethics Committee of China Medical University. The participants took part voluntarily, and their identities remained anonymous. We protected their privacy and maintained the confidentiality of personal records when processing personal data.

Study design and sample

We performed a cross-sectional survey in Liaoning Province, China, from July to December 2020. We recruited patients with cervical cancer from 3 hospitals, which were important providers of cancer treatment services in Liaoning Province. A random sampling method was adopted in this study. The subjects of this study were continuously selected from those who met the inclusion criteria. The eligibility criteria were (1) at least 18 years old; (2) pathologically proven cervical cancer; and (3) provided informed consent and voluntary participated. The exclusion criteria were (1) other serious physical diseases and (2) recent major traumatic events. All eligible patients were invited to participate by their oncologists or physicians. The survey instrument consisted of four questionnaires, and a total of 294 patients were enrolled. Ultimately, we received complete responses from 269 cervical cancer patients, with an effective response rate of 91.5%.

Demographic characteristics

We examined age, education level, marital status, and family monthly income (RMB: Yuan) in this study. We divided age into three ranges: ≤ 45, 46–55, and > 55 years. Options for marital status included “married/living with a partner” and “single/widowed/divorced.” We categorized education levels as “middle school or below” and “junior school and above”. We divided income into two levels: <3000 and ≥ 3000 RMB.

The measurement of symptoms of depression and anxiety

We chose the Chinese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) to measure depression symptoms [49]. Participants were asked to rate the number of times in the previous week that they had experienced depressive symptoms (e.g., low mood, anhedonia, lack of appetite, difficulty concentrating). This questionnaire included 20 items. Each item had 4 responses, ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always), and overall scores ranged from 0 to 60. The CES-D was used to survey symptoms over the span of one week. A higher average score represented a higher level of depression. A standard CES-D score ≥ 16 indicated depressive symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the CES-D was 0.905 in this study.

We evaluated anxiety symptoms using the Chinese version of the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) [50]. This scale contained 20 items, with each item scored from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The standard total score was obtained from the raw total score via the following formula: standard total score = int (1.25*raw total score). Higher scores represented higher anxiety symptoms. The scale has good reliability and validity and has been widely used in Chinese populations [51]. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the Zung SAS was 0.850.

Measurement of perceived social support

We chose the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) [52] to assess the PSS of cervical patients. The Chinese version of this scale has good reliability and validity [71]. The MSPSS contained 12 items. The score of each item ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The higher the total score, the higher the level of PSS. In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.910.

The measurement of sense of coherence

The Sense of Coherence Scale was developed by Antonovsky [54]. It consisted of three dimensions (comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness) and had 13 items. This scale was used to assess the internal stability of individuals. The items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging 1 to 7. The scale had a total score of 13 to 91. The higher the total score, the stronger the SOC [55]. In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of SOC was 0.807.

Clinical condition variables

We assessed three clinical condition factors, including new diagnosis, the presence of metastasis, and cancer stage. We divided new diagnosis and the presence of metastasis into responses of “yes” and “no.” We divided cancer stage into three ranges: “I,” “II,” and “III + IV.”

Statistical analysis

We processed all analyses using IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 (IBM, Asia Analytics Shanghai). We regarded statistical significance as a two-tailed p value < 0.05. We described demographic and clinical characteristics using the mean, standard deviation (SD), number (n), and percentage (%). We compared the differences in depressive and anxiety symptoms among each demographic and clinical group via t tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). We employed Pearson correlation to examine correlations among the continuous variables. We used hierarchical regression analysis to explore the relationship of PSS and SOC with depressive and anxiety symptoms and explore the possibility of a mediating role of SOC in the relationship between PSS and depressive and anxiety symptoms. We utilized the PROCESS macro (version 3.0 by Andrew F. Hayes) for SPSS to calculate the size of the mediating role and test the hypothesis. To verify whether the mediating effect of SOC was statistically significant with 5,000 bootstrap samples [53]. The differences in scale scores were explained by standardized total scores. We considered significant variables to be control variables. The independent variable was PSS, with depressive and anxiety symptoms serving as the outcomes and SOC as the mediator variable. The “c path” refers to the relationship between PSS and symptoms of depression and anxiety, while the “a*b path” represents the mediating role of SOC. If the absolute value of the “c’ path” coefficient shrinks more than that of the “c path,” a mediating role of SOC may exist. It is only when the confidence interval of the indirect effect does not contain zero that a mediating effect is thought to exist.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants. Among the 269 respondents whose ages ranged from 27 to 77 years, the average age was 53.45 ± 9.35 years. Most of the patients (94.3%) were married or living with a partner, and 68.0% had received a middle school education. In relation to the clinical variables, a minority of the participants (23.1%) were diagnosed at cancer stages III and IV, and 88.1% were newly diagnosed patients. Approximately 70.6% of the participants were free of metastases.

As shown in Table 1, the effect of marital status on depressive symptoms was statistically significant (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the effect of age, education level, income level, the presence of metastasis, new diagnosis, or stage of cancer on depressive symptoms in the descriptive statistics (p > 0.05). The descriptive statistics showed that the effects of age on anxiety symptoms were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Education level, marital status, income level, the presence of metastasis, new diagnosis, and cancer stage made no significant difference in the influence of anxiety symptoms (p < 0.05).

Correlations among the continuous variables

We computed Pearson’s correlation coefficients among PSS, SOC, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms. As shown in Table 2, depressive and anxiety symptoms were negatively associated with PSS and SOC.

Hierarchical regression analysis

Table 3 shows the results of the association between social support and depressive symptoms by hierarchical regression analysis. First, according to the results of univariate analysis, we added age and marital status (P < 0.1) as control variables. In the second step, PSS was added. Finally, we added SOC. After adjusting for age in Step 2, PSS could negatively predict depressive symptoms (β= −0.435, P < 0.01). PSS accounted for an additional 18.7% of the variance in the dependent variable. In Step 3, SOC negatively predicted depressive symptoms (β= −0.520, P < 0.01), which explained an additional 21.7% of the variance. After adding SOC, the absolute value of the regression coefficient of PSS on depressive symptoms decreased from 0.435 to 0.218. Thus, SOC might play a mediating role in the relationship between PSS and depressive symptoms in cervical cancer patients.

Table 4 shows the results of the association between social support and anxiety symptoms by hierarchical regression analysis. After adjusting for age and marital status (P < 0.1) in Step 2, PSS negatively predicted anxiety symptoms (β= −0.326, P < 0.01). PSS accounted for an additional 10.6% of the variance of the dependent variable. In Step 3, SOC negatively predicted anxiety symptoms (β= −0.325, P < 0.01), which explained an additional 8.6% of the variance. When we added SOC, the absolute value of the regression coefficient of PSS on anxiety symptoms decreased from 0.326 to 0.188. Thus, SOC could probably function as a mediator in the association of PSS with anxiety symptoms in cervical cancer patients.

Mediating role of SOC

Table 5 presents the path coefficients a (between PSS and the mediator) and b (between the mediator and depressive symptoms), as well as the a*b products. The effect of PSS on the SOC was 0.425. In line with the results from hierarchical multiple regression analysis, SOC was significantly and negatively associated with depressive symptoms after controlling for age, marital status, and PSS. Each BCa 95% CI for a*b of SOC, excluding 0, indicated that it had a significant mediating effect when it was added to the model. Hence, we found a significant mediating role of SOC in the association between PSS and depressive symptoms in cervical cancer patients. Formula (a*b/c) was used to calculate the proportion of the mediating effect. The mediating effect of PSS on physical depressive symptoms was 49.78%.

The path coefficients a (between PSS and the mediator) and b (between the mediator and anxiety symptoms), as well as the a*b products, are presented in Table 6. The effect of PSS on SOC was 0.426. Consistent with the results from hierarchical multiple regression analysis, SOC was significantly and negatively associated with anxiety symptoms after controlling for age, marital status, and PSS. Each BCa 95% CI for a*b of SOC, excluding 0, indicated a significant mediating effect when it was added to the model. Therefore, the significant mediating role of SOC in the association between PSS and anxiety symptoms was revealed among patients with cervical cancer. We used the formula (a*b/c) to calculate the proportion of mediation roles. The mediating effect of PSS on physical anxiety symptoms was 41.73%.

Discussion

In our study, we found no significant difference in the clinical variables regarding depressive and anxiety symptoms. However, some studies found that cancer stage is a disease-related factor influencing depression and anxiety [56,57,58]. Hanprasertpong et al. [59] revealed that there is no significance in cancer stage and diagnosis. Yang et al. [57] found that metastasis can’t predict depression and anxiety. Possible reasons for these inconsistent findings could be differences in patients’ characteristics and measurement tools.

We found that PSS was a positive coping resource for symptoms of depression and anxiety among cervical cancer patients, which was consistent with previous findings among various populations [47, 60,61,62,63]. Cervical cancer patients may worry about the impact on their personal health and daily life and may have negative emotions [7, 8]. Social support can promote positive behavior and reduce negative emotions [61]. The main effect model of social support plays a general role in the maintenance of individual mental health [19]. The higher the level of social support, the more an individual can accept the changes in disease and the less psychological pressure [47, 62, 63]. Family members and friends, as important supporters of patients’ emotions, can help reduce the pressure of the disease by increasing life help and care, thus preventing the occurrence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients. Therefore, a high level of social support can alleviate the negative impact of the pressure of disease, thereby reducing the generation of depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients.

Both previous studies and our findings strongly suggest that social support is significantly associated with a higher SOC [34,35,36,37, 64]. Similar to other studies [35, 38, 65], we found that social support may be an important cornerstone in the restoration of a person’s sense of coherence. Social support provides resources for people to cope with various challenges in life, and it can satisfy the psychological needs of an individual, affect internal stability, and improve internal resources. SOC is an important psychological resource that can be strengthened by social support [35, 38].

In addition, our results showed that SOC was negatively correlated with depressive and anxiety symptoms, which is in line with prior outcomes [66, 69]. The same conclusion was made for patients with breast and lung cancer, despite different samples [67, 68]. Schmuck et al. found that strong SOC emerged as the strongest predictor for less severe symptoms of anxiety and depression among HCWs [43]. A previous study investigated 170 spousal caregivers, and high SOC was found to be a protective factor against depression [66]. Individuals with high SOC are better at coping with various pressures (such as diseases, work pressures or adverse social environments) in an effective and flexible way, reducing the damage of stress to health by reducing the adverse physiological reactions and negative emotions related to stress perception.

We found that SOC mediated the relationship between social support and depressive and anxiety symptoms, indicating that low levels of social support are likely to lessen cervical cancer patients’ anxiety and depressive symptoms via their SOC levels. In the main effect model of social support, social support indirectly improves mental health by improving internal mental resources, including SOC. According to Kase et al. [31], SOC mediates the relationship between social support and depressive and anxiety symptoms in Japanese university students, which further supports this mechanism and suggests that SOC may mediate the relationship between social support and depressive and anxiety symptoms in cervical cancer patients. According to previous studies [37, 70], SOC can also act as a mediator among other variables, such between perceived stress and depression among older stroke patients [70] and between social support and self-management among hemodialysis patients [37]. These results further prove the mediating role of SOC. For this reason, medical staff should actively evaluate the level of SOC in newly diagnosed cervical cancer patients to prepare for early intervention.

Based on the above research, we propose some suggestions for clinical work. Many cancer patients have difficulty easily and freely maintaining a normal life under the influence of low PSS and are eager to obtain help. Thus, in caring for patients with cervical cancer, we should pay attention to their existing social support system, guiding patients to actively seek potential social resources and strengthening communication among patients and family members, friends, colleagues, and health care workers. Moreover, medical staff should pay attention to guiding patients to correctly understand their disease and relieve their anxiety and depression.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional study. Therefore, we were unable to confirm the exact causal relationship among the study variables. Second, we recruited only 269 cervical cancer patients from hospitals in Liaoning Province, China. Third, we did not examine all the relevant factors. Despite the limitations, we have obtained important evidence on the effects of PSS on depressive and anxiety symptoms in Chinese cervical cancer patients. We also tested whether SOC mediates the effect of PSS on symptoms of depression and anxiety using the bootstrapping method. In the future, we will conduct further research recruiting cervical cancer patients from the western and southern parts of China to include a more diverse sample. We will also use longitudinal design methods to infer causality, and we will study more related factors.

Conclusions

In sum, in cervical cancer patients, PSS and SOC were negatively correlated with depressive and anxiety symptoms. SOC played a mediating role in the relationship between PSS and depressive and anxiety symptoms. Strategies and measures to improve SOC may protect against the impact of PSS on depressive and anxiety symptoms in cervical cancer patients.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

World Cancer Report. Available online at: https://publications.iarc.fr/586 (accessed November 02, 2021).

Chen W et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 66(2), 115–32. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21338

Bujnak AC, Tewari KS. Should adjuvant chemotherapy be formally studied among patients found to have pelvic lymph node metastases following radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy for early-stage cervical cancer? J Gynecol Oncol. 2021;32(4):e62. https://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2021.32.e62

Xu Y, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy increases the 5-year overall survival of patients with resectable cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;60(3):433–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2021.03.008

Zhang G, et al. Post-operative small pelvic intensity-modulated radiation therapy for early-stage cervical cancer with intermediate-risk factors: efficacy and toxicity. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2021;51(6):905–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyab047

Whop LJ, et al. Achieving cervical cancer elimination among indigenous women. Prev Med. 2021;144:106314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106314

Cull A, et al. Early stage cervical cancer: psychosocial and sexual outcomes of treatment. Br J Cancer. 1993;68(6):1216–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1993.507

Hotopf M et al. (2002)Depression in advanced disease: a systematic review Part 1. Prevalence and case finding. Palliat Med 16(2), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1191/02169216302pm507oa

Yang YL et al. (2013)The prevalence of depression and anxiety among Chinese adults with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 13, 393. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-393

Park SY, et al. Quality of life and sexual problems in disease-free survivors of cervical cancer compared with the general population. Cancer. 2007;110(12):2716–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23094

Lebel S, Devins GM. ,(2008)Stigma in cancer patients whose behaviour may have contributed to their disease. Future Oncol. 4(5), 717–33. https://doi.org/10.2217/14796694.4.5.717

Kobayashi M, et al. Psychological distress and quality of life in cervical cancer survivors after radiotherapy: do treatment modalities, disease stage, and self-esteem influence outcomes? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19(7):1264–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a3e124

Distefano M, et al. Quality of life and psychological distress in locally advanced cervical cancer patients administered pre-operative chemoradiotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111(1):144–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.06.034

Ferrandina G et al. (2012)Quality of life and emotional distress in early stage and locally advanced cervical cancer patients: a prospective, longitudinal study. Gynecol Oncol 124(3), 389–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.09.041

Carter J, et al. A 2-year prospective study assessing the emotional, sexual, and quality of life concerns of women undergoing radical trachelectomy versus radical hysterectomy for treatment of early-stage cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119(2):358–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.07.016

Aktan NM. ,(2010)Functional status after childbirth and related concepts. Clin Nurs Res 19(2), 165–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773810369372

Stapleton LR et al. (2012)Perceived partner support in pregnancy predicts lower maternal and infant distress. J Fam Psychol 26(3), 453–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028332

Proceedings of the 2015 11th International Conference on Innovations. in Information Technology (IIT)[C]// International Conference on Innovations in Information Technology. IEEE Computer Society, 2015.

Stice E, Ragan J, Randall P. Prospective relations between social support and depression: differential direction of effects for parent and peer support? J Abnorm Psychol. 2004 Feb;113(1):155–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14992668/

Lynch TR, et al. Perceived social support among depressed elderly, middle-aged, and young-adult samples: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. J Affect Disord. 1999 Oct;55(2–3):159–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00017-8

Hart KE, Hittner JB. Irrational beliefs, perceived availability of social support, and anxiety. J Clin Psychol. 1991 Jul;47(4):582–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679. )47:4%3C582::aid-jclp2270470418%3E3.0.co;2-z.

Fisher HM et al. (2021)Relationship between social support, physical symptoms, and depression in women with breast cancer and pain. Support. Care Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06136-6

Hill EM, Hamm A. ,(2019)Intolerance of uncertainty, social support, and loneliness in relation to anxiety and depressive symptoms among women diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Psychooncology 28(3), 553–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4975

Dour HJ, et al. Perceived social support mediates anxiety and depressive symptom changes following primary care intervention. Depress Anxiety. 2014 May;31(5):436–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22216

Hourani L et al. Longitudinal study of resilience and mental health in Marines leaving military service. J Affect Disord. 2012 Jul;139(2):154 – 65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.008. Epub 2012 Mar 3. PMID: 22381952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.008.

Bonanno GA, Galea S, Bucciarelli A, Vlahov D. What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007 Oct;75(5):671–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.75.5.671

Hyde LW, Gorka A, Manuck SB, Hariri AR. Perceived social support moderates the link between threat-related amygdala reactivity and trait anxiety. Neuropsychologia. 2011 Mar;49(4):651–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.08.025. Epub 2010 Sep 9.

Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):725–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-Z

Antonovsky A. Health, stress, and coping. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1979. [Google Scholar].

Kase T, Endo S, Oishi K. Process linking social support to mental health through a sense of coherence in japanese university students. Ment Health Prev. 2016;4(3–4):124–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2016.05.001. [Google Scholar].

Jeong YJ, Koh CK. Female nursing graduate students’ stress and health: the mediating effects of sense of coherence and social support. BMC Nurs. 2021 Mar 11;20(1):40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00562-x

Casellas-Grau A et al. (2016)Positive psychological functioning in breast cancer: An integrative review. Breast 27, 136–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2016.04.001

Feldt T et al. Structural validity and temporal stability of the 13-item sense of coherence scale: prospective evidence from the population-based HeSSup study.[J]. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation,2007,16(3). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-006-9130-z

Pasek M, Dębska G, Wojtyna E. Perceived social support and the sense of coherence in patient-caregiver dyad versus acceptance of illness in cancer patients. J Clin Nurs. 2017 Dec;26(23–24):4985–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13997

Zhan T, Li H, Ding X. Can social support enhance sense of coherence and perceived professional benefits among Chinese registered nurses? A mediation model. J Nurs Manag 2020 Apr;28(3):488–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12931

Song YY et al. Social Support, Sense of Coherence, and Self-Management among Hemodialysis Patients. West J Nurs Res 2022 Apr;44(4):367–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945921996648

Malinauskiene V, Leisyte P, Malinauskas R. Psychosocial job characteristics, social support, and sense of coherence as determinants of mental health among nurses. Med (Kaunas). 2009;45(11):910–7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20051724/

Skärsäter I, et al. Sense of coherence and social support in relation to recovery in first-episode patients with major depression: a one-year prospective study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2005 Dec;14(4):258–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-0979.2005.00390.x

Langeland E, Wahl AK. The impact of social support on mental health service users’ sense of coherence: a longitudinal panel survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009 Jun;46(6):830–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.12.017

Drageset J, Natvig GK, et al. Sense of coherence among cognitively intact nursing home residents–a five-year longitudinal study. Aging Ment Health. 2014 Sep;18(7):889–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.896866

Ngai FW, Ngu SF. Family sense of coherence and quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2013 Oct;22(8):2031–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0336-y

Schmuck J et al. Sense of coherence, social support and religiosity as resources for medical personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic: A web-based survey among 4324 health care workers within the German Network University Medicine. PLoS One 2021 Jul 26;16(7):e0255211. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255211

Eriksson M, Lindström B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006 May;60(5):376–81. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.041616. PMID: 16614325; PMCID: PMC2563977.

Myers SB, et al. Social-cognitive processes associated with fear of recurrence among women newly diagnosed with gynecological cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(1):120–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.10.014

Ozga M, et al. A systematic review of ovarian cancer and fear of recurrence. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(6):1771–80. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515000127

MacLeod S, et al. The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2016;37(4):266–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.02.014

Pasricha M et al. Sense of Coherence, Social Support, Maternal-Fetal Attachment, and Antenatal Mental Health: A Survey of Expecting Mothers in Urban India. Front Glob Womens Health 2021 Sep 7;2:714182. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2021.714182

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12(6):371–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0

Zi J et al. (2020)Anxiety administrated by dexmedetomidine to prevent new-onset of postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass graft. Int Heart J 61(2), 263–72. https://doi.org/10.1536/ihj.19-132

Zimet GD et al. (1990)Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess 55(3–4), 610–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 2008 Aug;40(3):879–91. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879

Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993 Mar;36(6):725–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-z

Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12050

Gu Z et al. Interaction of anxiety and hypertension on quality of life among patients with gynecological cancer: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2023 Jan 11;23(1):26. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36631792/

Yang YL et al. Prevalence and associated positive psychological variables of depression and anxiety among Chinese cervical cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2014 Apr 10;9(4):e94804. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094804

Tosic Golubovic S, Andjelkovic Apostolovic M, Stanojevic M, Kostic J et al. Risk Factors and Predictive Value of Depression and Anxiety in Cervical Cancer Patients. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022 Apr 2;58(4):507. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35454346/

Hanprasertpong J, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence and its predictors among cervical cancer survivors. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Nov;28(6):e72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5641523/

Zamanian H, et al. Perceived social support, coping strategies, anxiety and depression among women with breast cancer: evaluation of a mediation model. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;50:101892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101892

Mache S, et al. Managing work-family conflict in the medical profession: Working conditions and individual resources as related factors. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e006871. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006871

Fisher HM, et al. Relationship between social support, physical symptoms, and depression in women with breast cancer and pain. Support. Care Cancer. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06136-6

Yu M, et al. The mediating role of perceived social support between anxiety symptoms and life satisfaction in pregnant women: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):223. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01479-w

Fujitani T et al. Association of social support with gratitude and sense of coherence in Japanese young women: a cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2017 Jun 27;10:195–200. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s137374

Skärsäter I, et al. Sense of coherence and social support in relation to recovery in first-episode patients with major depression: a one-year prospective study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2005 Dec;14(4):258–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-0979.2005.00390.x

López-Martínez C, Frías-Osuna A, Del-Pino-Casado R. Sentido de coherencia y sobrecarga subjetiva, ansiedad y depresión en personas cuidadoras de familiares mayores [Sense of coherence and subjective overload, anxiety and depression in caregivers of elderly relatives]. Gac Sanit. 2019;33(2):185–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2017.09.005

Liu B, et al. Correlations of social isolation and anxiety and depression symptoms among patients with breast cancer of Heilongjiang province in China: the mediating role of social support. Nurs Open. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.876

Togas C, Anagnostopoulos F, Alexias G. Sense of coherence, self-disclosure, and depression in lung cancer patients. Open J Med Psychol. 2021;10(1):11–26. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojmp.2021.101002

Eindor-Abarbanel A, et al. Important relation between self-efficacy, sense of coherence, illness perceptions, depression and anxiety in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/flgastro-2020-101412

Guo LN, et al. Perceived stress and depression amongst older stroke patients: sense of coherence as a mediator? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;79:164–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.08.010

Zhong Y, Wang J, Nicholas S. Social support and depressive symptoms among family caregivers of older people with disabilities in four provinces of urban China: the mediating role of caregiver burden. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1403-9

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patients who participated in this study, as well as all the teachers and teammates who assisted in obtaining written informed consent for the survey and in distributing the questionnaires to the participants.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qi Li contributed to formal analysis and investigation and wrote the manuscript. Li Liu was responsible for methodology and writing (review and editing). Zhihui Gu, Mengyao Li, and Chunli Liu contributed to the investigation and writing (review and editing). Hui Wu was responsible for data curation, methodology, project administration and supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was in accordance with the ethical standards and was approved by the Ethics Committee of China Medical University. The participants took part voluntarily and remained anonymous. We protected their privacy and maintained the confidentiality of personal records when processing personal data. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. We obtained informed consent from all individual patients included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Q., Liu, L., Gu, Z. et al. Sense of coherence mediates perceived social support and depressive and anxiety symptoms in cervical cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 23, 312 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04792-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04792-y