Abstract

Childhood and adolescence are critical periods for physical and mental development; thus, they are high-risk periods for the occurrence of mental disorders. The purpose of this study was to systematically evaluate the association between bullying and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. We searched the PubMed, MEDLINE and other databases to identify studies related to bullying behavior and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. A total of 31 studies were included, with a total sample size of 133,688 people. The results of the meta-analysis showed that the risk of depression in children and adolescents who were bullied was 2.77 times higher than that of those who were not bullied; the risk of depression in bullying individuals was 1.73 times higher than that in nonbullying individuals; and the risk of depression in individuals who bullied and experienced bullying was 3.19 times higher than that in nonbullying-bullied individuals. This study confirmed that depression in children and adolescents was significantly associated with being bullied, bullying, and bullying-bullied behavior. However, these findings are limited by the quantity and quality of the included studies and need to be confirmed by future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Depression refers to a persistent change in mood such as feelings of loss, sadness, and hopelessness [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, the number of depressed people worldwide has reached 264 million [2]. Epidemiological studies and clinical interviews show that children and adolescents have high incidence rates of depression, ranging from 2 to 8%. The detection rate of depression in adolescents in China is 15.7—29% [3]. Although depression among adolescents can disappear, 40—70% of children and adolescents still have the possibility of relapse within 5 years [4]. Indeed, depression is one of the most common mental health problems in children and adolescents and mainly manifests as a persistent decline in academic performance, feelings of worthlessness, difficulty in making friends, and poor sleep quality [5, 6]. Depression is very common among adolescents and affects adolescents’ interpersonal relationships, academic performance, and hobbies as well as their physical and mental health; severe depression may even be life-threatening [7]. Suicide is the third leading cause of death among children and adolescents, and depression is the leading cause of suicide among adolescents. A study in China reported that the incidence of nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) in children and adolescents with depression was as high as 44.0 to 61.2% [8].

In recent years, given rapid advances in news coverage and social media, harmful incidents in schools have been reported, and school bullying of children and adolescents has attracted more attention from society as a whole. Children and adolescents are exposed to the social environment during their growth. In this environment, bullying is used to solve conflicts. They are more likely to show aggressive behavior and regard bullying as a way to solve conflicts [9]. Between 2005 and 2013, the incidence of bullying in American schools was between 20 and 30% [10]. In Chinese middle school students, the bullying rate is 1.68% ~ 10.60%, the victimization rate is 5.91% ~ 25.70%, and the bullying victimization rate is 3.28% ~ 14.70% [11]. Additionally, with the advent of the internet era, cyberbullying has emerged as a new form of bullying; the incidence of cyberbullying has increased each year, attracting attention from researchers worldwide. A study by Pillkey and Jacqueline found that 37.8% of students experienced cyberbullying, 56% of students had witnessed cyberbullying, and the incidence of cyberbullying among eighth-grade students was as high as 42.1% [12]. Studies by Sampasakanyinga [13] and Hinduja [14] reported that victims of cyberbullying and school bullying have significantly greater suicide intent. Compared with people who were not bullied, the incidence of negative outcomes such as depression, anxiety, suicide, and loneliness was higher among those who were bullied. In addition, because the bully has no experience of being bullied, it is easy to ignore the harm caused by the bullying behavior, while people who are bullying and being bullied are more able to perceive the pain caused by the bullying; therefore, the twin pressures of bullying and being bullied combined with poor social and psychological function can increase the likelihood of depression, anxiety and other negative feelings [15, 16]. It can be seen that bullying, being bullied and bullying-being bullied should all receive higher social attention, and the physical and mental development of children and adolescents should not be ignored.

In recent years, studies in China and other countries have found that bullying and being bullied predict the occurrence of depression in children and adolescents [17]. In general, in the past meta-analysis, bullying and bullying—being bullied were not included in the study, and the relationship between the above three factors and depression was unclear. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to summarize the relevant research and explore associations through a meta-analysis. Specifically, the investigated associations included the relationships of bullying, being bullied, bullying and being bullied (hereafter, bullying-bullied) with depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. Ideally, these findings will inform and guide the development of preventive measures, thereby promoting the physical and mental health development of children and adolescents.

Methods

Protocols and registration

The study protocol was prospectively registered on the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (INPLASY) database (registration number: 202270087). The study was conducted based on the Cochrane Collaboration’s guidelines. The screening of eligible studies and data reports was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [18].

Literature search strategy

The PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, CNKI, and WanFang databases were electronically searched to identify relevant studies on bullying and depression in children and adolescents. The Chinese search terms included “children”, “adolescents”, “bullying”, “bullied”, “depression”, etc. The English search terms included “adolescent”, “teen”, “teenager”, “youth”, “female”, “male”, “child”, “children”, “bullying”, “depression”, “depressive symptoms”, “emotional depression”, etc. The search was carried out using a combination of subject headings and keywords.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

We included cross-sectional studies on the association between bullying and depression in children and adolescents. Eligible studies were published in Chinese or English, and the main subjects were children and adolescents, ranging in age from 6 to 18 years old. Bullying behavior included verbal bullying and was defined as follows: in the past 12 months, an individual or group engaged in persistent, repeated negative behavior toward other individuals or groups, such as verbal behavior (e.g., ridicule, nicknames, or spreading rumors to isolate others) or physical contact (e.g., hitting, kicking, or shoving). Being bullied was defined as an individual or group subjected to the above behavior by other individuals or groups. Finally, bullying-bullied refers to individuals that both bullied and were bullied by other individuals. The outcome measure was the incidence of depression, based on clear diagnostic criteria in the literature [19].

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies not published in Chinese or English, (2) duplicate studies, (3) studies with unavailable data, and (4) studies lacking important information that was unable to be obtained (i.e., the author was contacted but did not respond).

Literature screening and data extraction

Two reviewers independently screened the literature, extracted the data and cross-checked it. In cases of disagreement, a third party was consulted to reach a decision. We also contacted the authors of studies to obtain important information not reported in the publication. During the literature search, potentially relevant studies were identified by screening the title and abstract; after excluding obviously irrelevant studies, the full text of these studies was reviewed to determine its eligibility for inclusion. The data extracted included the following: (1) basic information regarding the included studies, including the first author and publication date; (2) baseline characteristics of the research subjects, including the sample size of each group and the age and sex of the participants; (3) the specific methodology (e.g., follow-up duration); (4) key elements related to the risk of bias assessment; and (5) relevant outcome indicators and outcome assessments.

Risk of bias in the included studies

Cross-sectional studies were assessed for risk of bias using the quality assessment criteria recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) [20]. This scale has 11 items, each of which are scored as “Yes” (1 point) or "No/Unclear" (0 points), for a total of 11 potential points. A score of 0–3 indicates low-quality literature, 4–7 indicates medium-quality literature, and 8–11 indicates high-quality literature.

Statistical analysis

Stata 14.0 was used for statistical analysis, and the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) are reported to indicate effects. The χ2 test (test level α = 0.1) and I2 statistic were used to determine the size of heterogeneity among the results of the included studies. When P ≥ 0.1 and I2 < 50%, the heterogeneity of the included literature was low, and a fixed-effect model was used for the meta-analysis. In contrast, P < 0.1 and I2 ≥ 50% indicated that the included studies had nonnegligible heterogeneity, and a random-effects model was used for meta-analysis. Sensitivity analysis or subgroup analysis was performed on the results of studies with large heterogeneity, and studies were excluded if necessary to ensure the reliability and stability of the study results. Egger's test was used to assess publication bias.

Results

Literature search

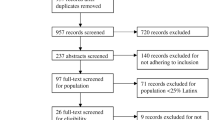

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA [18] flow chart of the study selection and exclusion process. An electronic database search identified 1,989 records. After sorting and eliminating duplicates, 425 articles were screened by title and abstract. A total of 97 relevant full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 31 were cross-sectional surveys and included in the final analysis. The most common reason for exclusion was a lack of available data.

Quality assessment

Table 1 shows the characteristics of all included studies. A total of 31 studies were included in this meta-analysis. The overall quality score of the articles had an average of 6.94 ± 1.00 points; this indicates a moderately high quality, ranging from high-quality literature (a maximum of 8 points) to medium-quality literature (a minimum of 5 points). Most articles did not describe how they evaluated and/or controlled for confounders and did not explain how missing data were handled in the analysis.

Description of included studies

In most studies, female participants made up the majority (n = 18) (Table 1). Most studies were conducted in Asia (n = 14), especially in China, while other studies were from Europe (n = 13) and Oceania (n = 2). Most studies included adolescents of multiple ethnicities (n = 10). All research subjects were from schools, including middle and high schools. The research categories included bullying individuals (n = 31), bullied individuals (n = 11), and bullying-bullied individuals (n = 9). The bullying types included traditional bullying (n = 16), cyberbullying (n = 11), and both (n = 4).

Most studies assessed cyberbullying with a single measure (n = 9). For the assessment of depression, four studies used only one item. However, this single item assessed the two main symptoms of depression, "feelings of sadness and despair for approximately two weeks," which are equivalent to dysphoria and anhedonia.

Depression

Two studies did not specify an assessment item for depression [44, 50]. Data reported in ten studies were raw, and only crude ORs were extracted [21,22,23,24,25, 28, 33, 39, 47, 49]. Only three studies assessed differences between depression outcomes and frequency of cyberbullying [31, 46, 50]. Another study assessed differences in depression outcomes among two different groups of victims: cyberbullying victims (defined as those who experienced repeated bullying and a power imbalance) and victims of "generalized" cyberharassment [39].

Relationship between being bullied and depression in children and adolescents

A total of 31 studies were included in this analysis. The random-effects model showed that the risk of depression in children and adolescents who were bullied was 2.77 times higher than in those who were not bullied [OR = 2.77, 95% CI (2.29,3.35), P < 0.001] (Fig. 2). Sensitivity analysis was conducted by individually excluding each study; this analysis found no substantial change in the results, suggesting a stable pooled effect size (OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.83, 1.21). However, the funnel plot was obviously asymmetric (Fig. 3), and the results of Egger's test (t = 4.64, P < 0.05) suggest the presence of publication bias.

Taking the average age of the subjects as the covariate, the restricted maximum likelihood method was used for the single-factor meta-regression analysis. The results showed that there was a weak correlation between the age of the subjects and the occurrence of depression after being bullied – that is, age was not the source of heterogeneity in this study [B = -0.02, 95% CI (-0.33, 0.29)].

Relationship between bullying and depression in children and adolescents

A total of 11 studies were included in this analysis. The random-effects model showed that the risk of depression in bullying individuals was 1.73 times higher than that in nonbullying individuals [OR = 1.73, 95% CI (1.34, 2.23), P < 0.0001] (Fig. 4).

Relationship between bullying-bullied behavior and depression in children and adolescents

A total of 9 studies were included in this analysis. The results of the random-effects model showed that the risk of depression in those who both bullied and were bullied was 3.19 times higher than in nonbullying-bullied individuals [OR = 3.19, 95% CI (2.54, 4.01), P = 0.001] (Fig. 5).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was conducted based on sex, publication year, cultural background, sampling method, bullying type and article quality. The results showed significant differences in the effect size of the relationships between being bullied and depression in children and adolescents with different cultural backgrounds and bullying types (P < 0.001); the effect sizes were relatively low in studies from Asia and those on cyberbullying (Table 2).

Discussion

A total of 31 cross-sectional studies on the relationship between bullying and children and adolescents were included in this study. The results showed that bullying was a risk factor for depression in children and adolescents [OR = 2.77, 95% CI (2.29, 3.35), P < 0.001] (Fig. 2). Additionally, 11 studies showed that bullying children and adolescents also had a risk of depression [OR = 1.73, 95% CI (1.34, 2.23), P < 0.001] (Fig. 4). Furthermore, this study found that bullying—bullying children and adolescents have a higher risk of depression than the former two [OR = 3.19, 95% CI (2.54, 4.01), P = 0.001] (Fig. 5).

No previous meta-analysis has explicitly focused on the relationship between depression in children and adolescents and bullying, being bullied, bullying—being bullied. Our study is the first meta-analysis that includes 31 cross-sectional surveys focusing on the relationship between bullying behavior and depression in children and adolescents. Lutrick K [51] reported a positive relationship between being bullied and depression in children and adolescents through a meta-analysis, consistent with the results of the current study; however, their meta-analysis only evaluated the relationship between being bullied and depression in children and adolescents and focused on Latino populations, which are understudied. Recently, a meta-analysis conducted by Moore SE [52] found that bullying has negative impacts on mental health in children and adolescents, but the type of bullying examined was limited, and no systematic review of other types of bullying behavior has been conducted. Gini G demonstrated [53] an association between bullying and psychosomatic problems through a meta-analysis. However, the outcome of this meta-analysis was the incidence of psychosomatic problems in children and adolescents; although these psychosomatic problems included depression, the research object was not specific. In contrast, the target of this meta-analysis is depression. The target population is more accurate, covering a wider range of people (including people from Europe and Asia) and a larger sample size. We also evaluated the effects of bullying and bullying-bullied behavior on depression. The results may inform the prevention and control of depression in children and adolescents.

This meta-analysis showed that bullying is related to depression in children and adolescents, which is consistent with the findings of Fan H and Gao L [54, 55]. This association may be because adolescents who experience bullying perceive themselves more negatively, are more closed off, and are reluctant to seek outside support. A study by Duan S et al. showed that when children and adolescents are bullied, their emotions are greatly affected; this emotional harm is difficult to treat and reduces the individual's mental health, resulting in depression [56]. Additionally, victims of bullying are regarded as weak, even though they may have excellent grades in school. After being bullied, the victims are typically threatened with harm if they tell an adult [57]. These findings suggest that children and adolescents are at risk of suffering from depression due to bullying. While controlling bullying, the mental health problems of children and adolescents after bullying are still one of the key tasks of our medical care.

This meta-analysis found that bullying is a risk factor for depression in children and adolescents. This finding is consistent with that of Choi JK [55]. One explanation may be that bullying individuals have depression and choose to use aggression as a coping mechanism. In addition, bullying individuals are unable to normally communicate with their peers; thus, they are rejected and experience depression(Lee 2021). Relevant studies have shown that aggressive bullying individuals are prone to depressive symptoms and even self-loathing thoughts and behaviors, which may be related to symptoms that have a high co-occurrence with aggression, such as impulsivity and anger [56]. Therefore, we should not only guide the psychology of children and adolescents correctly to reduce the occurrence of bullying but also draw attention to the psychological health of children and adolescents who implement bullying in society, which is a problem that we cannot ignore.

The meta-analysis also found that of the three bullying categories, bullying-bullied behavior had the strongest association with depression in children and adolescents. A study in Macau, China showed that bullying-bullied individuals experienced the most negative emotions, such as depression and anxiety, and the lowest life satisfaction [57]. The probable cause is that bullying-bullied individuals experience the negative effects of both bullying and being bullied. These individuals exhibit poor psychosocial functioning, poor self-control, vulnerability to rejection from peer groups, and the highest levels of depression [58]. The meta-analysis results suggest that reducing bullying among children and adolescents will help to prevent and control the occurrence of depression. Additionally, psychological intervention may be needed for children and adolescents after experiences of bullying and being bullied.

The number of victims of cyberbullying has increased over the past decade, accompanied by increasing concern about the harmful effects of cyberbullying on victims. Multiple studies have linked traditional bullying among teenagers with depression, suicidal ideation, and nonfatal suicidal behavior [59, 60]. However, the psychological outcomes of cyberbullying are inconsistent and unclear, possibly because of its recent development. Some authors have argued that the consequences of cyberbullying are similar to those of traditional bullying [37, 61]; others believe that cyberbullying is more distressing than traditional bullying [62].

The subgroup analysis in this study showed that the risk of depression after being bullied in children and adolescents was significantly higher after 2015 than that before 2015. One explanation is that the recent technological advances and the internet age have facilitated the appearance of cyberbullying in the lives of children and adolescents. Thus, some children and adolescents may not only experience traditional bullying but also cyberbullying. As mentioned earlier, adolescence is a critical time for psychological development; thus, adolescents are at higher risk of depression. The results of this meta-analysis also indicate that the risk of depression in children and adolescents after being bullied is higher in Europe than in Asia; this may be because European countries carry out universal screening for depression in adolescents. In addition, in terms of screening tools, the Epidemic Investigation Center Depression Scale, the Children's Depression Scale, and the Patient Health Questionnaire are widely used to screen for depression in Chinese children and adolescents [63, 64]. However, the screening ability of these scale need to be further verified and revised, and their psychometric properties (such as sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy) should be determined according to different regions and survey samples. For example: the internal consistency for the CES-D was α = 0.78–0.79, but the subjects answered for a long time, had a high emotional load, and were sensitive to the project content. The content of the CES-DC is similar to that of the CES-D, but the former is more applicable to children and adolescents aged 6 to 17 years old because it uses simpler expressions [65]. The retest reliability of each item of SDS scale is 0.730 ~ 1.000, and the Cronbach α coefficients range from 0.782 ~ 0.784, indicating that it can be used for screening depression in adults and adolescents [66].

This study also found that the risk of depression was similar in children and adolescents who experienced traditional bullying or cyberbullying, suggesting that, while cyberbullying merits attention, school bullying should still be addressed. A variety of support should be included (e.g., from schools, relevant departments, and families) to bolster children’s mental health and provide timely support. Additionally, as traditional bullying, cyberbullying, and other types of bullying are related, more thorough and comprehensive bullying prevention programs and regulations are warranted to effectively reduce bullying among children and adolescents to promote healthy development.

In this meta-analysis, the heterogeneity of the included studies was high; after subgroup analysis (according to sex, sampling method, publication year, and region), I2 was still greater than 50%, suggesting that these factors may not have been the source of heterogeneity. Since the 31 included studies were from 13 countries, the definition or assessment of bullying and depression, location, participant ethnicity, and culture may have all contributed to the heterogeneity.

Limitations

Only cross-sectional data were included in this meta-analysis, which precludes determination of causal associations. Additionally, few studies have been conducted on bullying, bullying-bullied behavior and depression in children and adolescents, which may reduce the reliability of the results. Subgroup analysis was carried out to analyze the heterogeneity among studies. The results of the funnel plot and Egger's test showed that publication bias was present, suggesting that it may be caused by publication type (i.e., gray literature).

Conclusion

This meta-analysis shows that there is a significant correlation between depression and bullying, being bullied, and bullying-bullied behavior among children and adolescents. All three experiences are risk factors for depression. Subgroup analysis revealed that children and adolescents who have been bullied—bullied are most likely to suffer from depression. Ideally, these findings will inform and guide the development of preventive measures, thereby promoting the physical and mental health development of children and adolescents.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article and the original studies’ publications.

References

Mendelson T, Tandon SD. Prevention of Depression in Childhood and Adolescence. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2016;25(2):201–18.

Jayanthi P, Thirunavukarasu M, Rajkumar R. Academic stress and depression among adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52(3):217–9.

Wang LF, Feng ZZ, Yang GY. The epidemiological characteristics of depressive symptoms in the left behind children and adolescents of Chongqing in China. J Affect Disord. 2015;177:36–41.

Choe CJ, Emslie GJ, Mayes TL. Depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;21(4):807–29.

Bar-Zomer J, Brunstein Klomek A. Attachment to parents as a moderator in the association between sibling bullying and depression or suicidal ideation among children and adolescents. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9(72):1–9.

Hazell P. Updates in treatment of depression in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(6):593–9.

Beck A, Leblanc JC, Morissette K. Screening for depression in children and adolescents: a protocol for a systematic review update. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):24.

Xu MG, Liu SM, Chen JL. The relationship between life events, emotional symptoms and non suicidal self injury behavior in adolescents with depression. J Psychiatry. 2020;33(06):420–3.

Morcillo C, Ramos-Olazagasti MA, Blanco C, et al. Socio-cultural context and bulling others in childhood. J Child Fam Stud. 2015;24(8):2241–9.

Robers S, Morgan RE, Zhang A. Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2014. Crime, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-199609000-00097.

Peng ZW, Ding CX, Chen XJ. Research progress on epidemic characteristics and prevention of campus bullying among middle school students in China. Inj Med (electronic version). 2019;8(03):41–7.

Pilkey JK. The nature and impact of cyberbullying on the middle school student. Walden University. 2011.

Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Roumeliotis P, Xu H. Associations between cyberbullying and school bullying victimization and suicidal ideation, plans and attempts among Canadian schoolchildren. PloS one. 2014;9(7):e102145.

Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2010;14(3):206–21.

Runions KC, Shaw T, Bussey K, et al. Moral disengagement of pure bullies and bully /victims: shared and distinct mechanisms. J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(9):1835–48.

Noorden TV, Haselager G, Cillessen A, et al. Empathy and involvement in bullying in children and adolescents: a systematic review. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(3):637–57.

Hysing M, Askeland KG, La Greca AM. Bullying involvement in adolescence: implications for sleep, mental health, and academic outcomes. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36(17–18):Np8992-9014.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Zaborskis A, Ilionsky G, Tesler R. The association between cyberbullying, school bullying, and suicidality among adolescents. Crisis. 2019;40(2):100–14.

Viswanathan HN, Salmon JW. Accrediting organizations and quality improvement. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6(10):1117–30.

Chen JY, Zhao Y, Li KH. the current situation of Internet bullying among children and adolescents and its correlation with anxiety and depression symptoms. Modern Prev Med. 2022;49(05):808–13.

Wang WK, Wang J, Ye MN. Analysis of the relationship between campus bullying and depression among urban adolescents in Nanchang. Modern Prev Med. 2021;48(16):2933–29370.

Xie Y, Chen BL. Study on the relationship between different bullying roles and depression in campus bullying. Soc Work Manag. 2021;21(03):5–14.

Liu XQ, Yang MS, Peng C. anxiety and depression of middle school students in different roles in campus bullying. Chin J Ment Health. 2021;35(06):475–81.

Chen T, Fan Y, Zhang ZH. Correlation between campus bullying and depression among middle school students in Jiangxi Province. Chin School Health. 2020;41(04):600–3.

Zhang ZW, Lou CH, Zhong XY. Correlation between different roles in campus bullying and depression. Chin School Health. 2019;40(02):228–31.

Kim JH, Kim JY, Kim SS. School violence, depressive symptoms, and help seeking behavior: a gender-stratified analysis of Biethnic adolescents in South Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2016;49(1):61–8 Yebang Uihakhoe chi.

Abd Razak MA, Ahmad NA, Abd Aziz FA. Being bullied is associated with depression among Malaysian adolescents: findings from a cross-sectional study in Malaysia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2019;31(8):30s–7s.

Rothon C, Head J, Klineberg E. Can social support protect bullied adolescents from adverse outcomes? A prospective study on the effects of bullying on the educational achievement and mental health of adolescents at secondary schools in East London. J Adolesc. 2011;34(3):579–88.

Alrajeh SM, Hassan HM, Al-Ahmed AS. An investigation of the relationship between cyberbullying, cybervictimization and depression symptoms: a cross sectional study among university students in Qatar. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(12):e0260263.

Donato F, Triassi M, Loperto I. Symptoms of mental health problems among Italian adolescents in 2017–2018 school year: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Environ Health Prev Med. 2021;26(1):67.

Jung YE, Leventhal B, Kim YS. Cyberbullying, problematic internet use, and psychopathologic symptoms among Korean youth. Yonsei Med J. 2014;55(3):826–30.

Lemstra ME, Nielsen G, Rogers MR. Risk indicators and outcomes associated with bullying in youth aged 9–15 years. Can J Public Health. 2012;103(1):9–13.

Selkie EM, Kota R, Chan YF. Cyberbullying, depression, and problem alcohol use in female college students: a multisite study. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2015;18(2):79–86.

Kaur J, Cheong SM, Mahadir NB. Prevalence and correlates of depression among adolescents in Malaysia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2014;26(5 Suppl):53s–62s.

Hansson E, Garmy P, Vilhjálmsson R. Bullying, health complaints, and self-rated health among school-aged children and adolescents. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(2):300060519895355.

Schneider SK, O’Donnell L, Stueve A. Cyberbullying, school bullying, and psychological distress: a regional census of high school students. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):171–7.

Liu X, Peng C, Yu Y. Association between sub-types of sibling bullying and mental health distress among Chinese children and adolescents. Front Psych. 2020;11:368.

Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ, Wolak J. Examining characteristics and associated distress related to Internet harassment: findings from the Second Youth Internet Safety Survey. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):e1169–77.

Sourander A, Klomek AB, Ikonen M. Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: a population-based study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(7):720–8.

Hemphill SA, Kotevski A, Heerde JA. Longitudinal associations between cyber-bullying perpetration and victimization and problem behavior and mental health problems in young Australians. Int J Public Health. 2015;60(2):227–37.

Messias E, Kindrick K, Castro J. School bullying, cyberbullying, or both: correlates of teen suicidality in the 2011 CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(5):1063–8.

Klomek AB, Marrocco F, Kleinman M. Peer victimization, depression, and suicidiality in adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38(2):166–80.

Goebert D, Else I, Matsu C. The impact of cyberbullying on substance use and mental health in a multiethnic sample. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(8):1282–6.

Landstedt E, Persson S. Bullying, cyberbullying, and mental health in young people. Scand J Public Health. 2014;42(4):393–9.

Chang FC, Chiu CH, Miao NF. The relationship between parental mediation and Internet addiction among adolescents, and the association with cyberbullying and depression. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;57(2):21–8.

Islam MI, Khanam R, Kabir E. Bullying victimization, mental disorders, suicidality and self-harm among Australian high schoolchildren: evidence from nationwide data. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292(3):113364.

Mereish EH, Sheskier M, Hawthorne DJ. Sexual orientation disparities in mental health and substance use among Black American young people in the USA: effects of cyber and bias-based victimisation. Cult Health Sex. 2019;21(9):985–98.

Mallik CI. Adolescent victims of cyberbullying in Bangladesh- prevalence and relationship with psychiatric disorders. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;48(3).

Elgar FJ, Napoletano A, Saul G. Cyberbullying victimization and mental health in adolescents and the moderating role of family dinners. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(11):1015–22.

Lutrick K, Clark R, Nuño VL. Latinx bullying and depression in children and youth: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):126.

Moore SE, Norman RE, Suetani S. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7(1):60–76.

Gini G, Pozzoli T. Association between bullying and psychosomatic problems: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):1059–65.

Fan H, Xue L, Zhang J. Victimization and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. J Affect Disord. 2021;294(10):375–81.

Gao L, Liu J, Yang J. Longitudinal relationships among Cybervictimization, peer pressure, and adolescents’ depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2021;286(5):1–9.

Duan S, Duan Z, Li R. Bullying victimization, bullying witnessing, bullying perpetration and suicide risk among adolescents: a serial mediation analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;273(4):274–9.

Choi JK, Teshome T, Smith J. Neighborhood disadvantage, childhood adversity, bullying victimization, and adolescent depression: a multiple mediational analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;279(6):554–62.

Hill RM, Mellick W, Temple JR. The role of bullying in depressive symptoms from adolescence to emerging adulthood: a growth mixture model. J Affect Disord. 2017;207(2):1–8.

Lahti A, Räsänen P, Riala K. Youth suicide trends in Finland, 1969–2008. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(9):984–91.

Thabrew H, Gandeza E, Bahr G. The management of young people who self-harm by New Zealand infant, child and adolescent mental health services: cutting-edge or cutting corners? Australas Psychiatry. 2018;26(2):152–9.

Collins L, Jp N. Cyber Bullying: The New Frontier. Teach Learn. 2004;1(3). https://doi.org/10.26522/tl.v1i3.97.

Dooley JJ, Pyzalski J, Cross D. cyberbullying versus face-to-face bullying a theoretical and conceptual review. Zeitschrift Fur Psychol J Psychol. 2009;217(4):182–8.

Yang WH, Xiong G. The validity and demarcation points of common depression scales in screening depression among adolescents in China. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2016;24(06):1010–5.

Liu ZX, Li J, Wang Y. structural verification and measurement equivalence of the Chinese version of children’s depression scale. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2019;27(06):1172–6.

Song C, Gadermann A, Zumbo B. Differential item functioning of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale among Chinese adolescents. Immigr Minor Health. 2022;24(3):790–3.

Philippot A, Dubois V, Lambrechts K. Impact of physical exercise on depression and anxiety in adolescent inpatients: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2022;301:145–53.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, China. (Grant No.82001444); Foundation of Nursing Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, China. (Grant No. HLKF2022-2); Sichuan Science and Technology Program. (Grant No. 2018JY0306).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ye Z was involved in all aspects of the study from Literature search, data extraction, analysis, interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript. Wu D was involved in all aspects of the study from Literature search, data extraction, analysis, interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript. He X was involved with the conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation. Ma Q was involved with the formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft, Writing Review & Editing. Peng J was involved with the formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft, Writing Review & Editing. Mao G was involved with the formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft, Writing Review & Editing. Feng L was involved with the formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft, Writing Review & Editing. Tong H was involved with the formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing Review & Editing. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, Z., Wu, D., He, X. et al. Meta-analysis of the relationship between bullying and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. BMC Psychiatry 23, 215 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04681-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04681-4