Abstract

Introduction and objectives

The aging population is expected to reach 2 billion by 2050, but the impact of somatic symptom disorder (SSD) on the elderly has been insufficiently addressed. We aimed to clarify the prevalence of SSD in China and to identify physical and psychological differences between the elderly and non-elderly.

Methods

In this prospective multi-center study, 9020 participants aged (2206 non-elderly adults and 6814 elderly adults) from 105 communities of Shanghai were included (Assessment of Somatic Symptom in Chinese Community-Dwelling People, clinical trial number NCT04815863, registered on 06/12/2020). The Somatic Symptom Scale-China (SSS-CN) questionnaire was used to measure SSD. Depressive and anxiety disorders were assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), respectively.

Results

The prevalence of SSD in the elderly was higher than that in the non-elderly (63.2% vs. 45.3%). The elderly suffered more severe SSD (20.4% moderate and severe in elderly vs. 12.0% in non-elderly) and are 1.560 times more likely to have the disorder (95%CI: 1.399–1.739; p < .001) than the non-elderly. Comorbidity of depressive or anxiety disorders was 3.7 times higher than would be expected in the general population. Additionally, the results of adjusted multivariate analyses identified older age, female sex, and comorbid physical diseases as predictive risk factors of SSD in the elderly group.

Conclusions

With higher prevalence of common physical problems (including hypertension, diabetes mellitus and cardio/cerebrovascular disease), the elderly in Shanghai are more vulnerable to have SSD and are more likely to suffer from comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders. SSD screening should be given more attention in the elderly, especially among older females with several comorbid physical diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction and objectives

As the world population ages rapidly, elderly adults (over 60 years old, as defined by World Health Organization [1]) now account for 13.5% of the global population [2] and 18.7% of the population of China [3]. With increasing life expectancy, longevity has increased from 66.5 years old in 2006 to 73.3 years old by 2019 [4]. By 2050, the number of aging people is expected to reach 2 billion [5]. However, the successful extension of the human life span raises a deeper demand for quality-of-life improvement, rather than solely extended living time.

Psychological problems are an important factor affecting the quality of life. Published in 2018, the “White Paper on Mental Health of Chinese Urban Residents” surveyed 1.13 million people from 556 medical institutions (health examination centers and general hospitals) on physical and psychiatric questions [6]. Based on these responses, 73.6% of urban residents were considered to have suboptimal mental health [6], indicating that psychological problems have become an inevitable hindrance to healthy development.

Since the elderly have grown into a larger entity, a special focus on the older population is needed. Compared with the non-elderly, the elderly population has unique social and biological characteristics. Generally, the elderly have a higher prevalence of hypertension [7], diabetes [8], and cardio/cerebrovascular (CV) diseases [9]. Their paces of life, occupational stressors, and marital statuses are different from those of non-elderly individuals. Therefore, this group may also have a different prevalence of somatic symptom disorder (SSD), depressive disorders, and anxiety disorders. While previous literature has investigated depressive or anxiety disorders in aged populations [10,11,12,13], SSD in the elderly has rarely been addressed. In a European study, SSD prevalence in the elderly was reported to range from 0–13.5%, based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV) criteria [14,15,16,17,18]. For example, Dehoust et al. reported that, overall, 3.88% of elderly participants met the criteria for any past‐year somatoform disorder based on the multi-center MentDis_ICF65 + study [18]. However, the diagnostic criteria for somatization disorder defined in the DSM‐IV have frequently been criticized as overly restrictive. Therefore, the DSM-5, which emphasizes broader concepts, now defines SSD as “symptoms that are difficult to explain after adequate evaluation; even when a significant medical disease is present.”

To the best of our knowledge, there is no research comparing the prevalence of SSD, depressive disorders, and anxiety disorders between elderly and non-elderly populations. Current data are not sufficient to determine the prevalence of SSD under DSM-5 criteria. As the clinical relevance of SSD in the elderly is uncertain, these studies are urgently required for the optimal allocation of medical resources and health management of elderly community members.

To screen for SSD, we designed a prospective cross-sectional study to assess physical and psychological characteristics in elderly people from 105 communities in Shanghai, China. Differs from SSD-12 (focuses mainly on psychological feelings, which views somatic discomfort as a general concept, and focuses on the impact of the disease on the individual), we previously developed the Somatic Symptom Scale-China (SSS-CN) questionnaire, a somatic and psychological symptom scale based on the DSM-5 that can be used to assess a combination of psychological, behavioral, and somatic symptoms and which is designed to assess both presence and severity of symptoms [19]. We validated the reliability and validity of this instrument in a previous study [20]. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) were used to evaluate depressive and anxiety disorders, respectively. The purpose of our study was threefold: (1) to clarify the prevalence of SSD, depressive disorders, and anxiety disorders in the elderly in China; (2) to identify physical and psychological differences between the elderly and non-elderly; and (3) to explore risk factors for SSD in the elderly.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This prospective cross-sectional study (Assessment of Somatic Symptom in Chinese Community-Dwelling People, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT04815863, registered on 06/12/2020) is a multicenter registry conducted in Shanghai, China, under the supervision of the Shanghai Association of Chinese Integrative Medicine.

A multistage and stratified systematic sampling technique was used to choose representative districts from sixteen districts in Shanghai, which were then divided into low, medium, and high economic levels according to the per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of each district in 2018. Eleven districts were selected proportionally and randomly and represented by 105 community health service institutions. Inclusion criteria were (a) voluntary participation and provision of written consent to participate in the study’s evaluation and assessment and (b) completion of the SSS-CN questionnaire, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) questionnaires. Exclusion criteria were (a) patients lacking self-assessed abilities or who refused to participate, (b) patients who have been previously confirmed to have serious mental disorders, mental retardation, or dementia, (c) patients with cancer or central nervous system diseases, (d) patients with any missing data within questionnaire items or with more than one item missing from sociodemographic information. The study was approved by institutional review committees at each center. The study is compliant with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki guidelines.

Definition of the elderly

Elderly populations were defined according to the World Health Organization recommendations [1]. People over age 60 are considered elderly in developing countries. In our study, participants were divided into two age groups: elderly (≥ 60 years) and non-elderly (18–60 years).

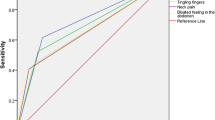

Description of SSS-CN and assessment of SSD

The SSS-CN questionnaire is self-administered with an abbreviated 20-item measure. Briefly, it is composed of four dimensions: physical disorders, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders and depressive and anxiety disorders. Half of the items ask about physical complaints (one item per body system). We validated the reliability and validity of this instrument in a previous study [21]. The total score can range from 20 to 80, and test–retest reliability was 0.9. To obtain accurate cutoff values in this group of populations, we randomly selected 202 participants who undertook both questionnaires to be interviewed by a physician team. The physician teams (physicians qualified as national psychological counsellors or psychologists) diagnosed SSD based on DSM-5 criteria. These physician assessments were used as the reference standard, and a cutoff value of 30 yielded an optimal sensitivity of 0.96 and specificity of 0.86. These findings were consistent with the research of Jiang et al. [19]. Thus, SSS-CN scores ranging from 20 to 29, 30–39, 40–59 and ≥ 60 correspond to normal, mild, moderate and severe SSD, respectively. The SSS-CN is attached in the Supplementary material.

Assessment of depressive and anxiety disorders

All participants were assessed for depressive and anxiety disorders according to the PHQ-9 and GAD-7, which evaluate the frequencies at which certain symptoms had been experienced over the last two weeks, ranging from 0 (‘not at all’) to 3 (‘nearly every day’). These questionnaires were self-administered. The cutoff values are listed below. For PHQ-9, scores of 5–9 indicate mild depressive disorder, 10–14 indicate moderate depressive disorder, 15–19 indicate moderately severe depressive disorder and ≥ 20 indicate severe depressive disorder [22]. For GAD-7, scores range from 0 to 21, with scores of 5–9, 10–14, and ≥ 15 representing mild, moderate, and severe anxiety symptom levels, respectively [23].

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

Sociodemographic data, including age, gender, level of education and marital status, were also collected. A semi-structured questionnaire concerning clinical characteristics was administered to survey participants’ medical and medication histories.

Data collection and management

The survey was conducted by trained surveyors. A community pilot study was conducted, and surveyors developed unified explanations of each item based on this pilot study to ensure sufficient understanding. Native Chinese language was used. Surveyors read the items and helped to fill out the questionnaires if the participants were illiterate. Surveyors and supervisors were trained to understand questionnaire contents and study procedures. Data were collected by trained clinical researchers, and data collection was supervised by specialist mental health workers.

Data were entered into the EpiData 3.1 (EpiData for Windows; EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark) database using dual data entry. Over 10% of the database was further audited, including logical consistency checks and extraction of information from participants’ community health records to ensure accuracy and completeness. A unique identifier number was assigned to each participant. Proper categorization and coding of data were performed during data cleaning phases. Database access was password-protected, and access was restricted to key team personnel.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics for each group, such as counts and percentages (%) for non-continuous variables, were reported for all sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. The prevalences of SSD of various severities for different genders and for participants diagnosed with depressive and anxiety disorders were calculated.

In order to assess whether SSD, depressive and anxiety disorders are associated with aged groups and whether depressive and anxiety disorders are associated with the severity of SSD, binary logistic regressions were performed, adjusting for gender, educational level (middle school and below, high school, college, master and above), marital status (never married, married, divorced, widowed), hypertension (yes/no), diabetes mellitus (yes/no), CV disease (yes/no), endocrine and metabolic disease except DM (yes/no), other diseases (yes/no), surgery (yes/no) and antipsychotic intake (yes/no) in all models.

Univariate analyses and binary logistic regression models were used to assess the effects of sociodemographic factors and clinical characteristics on SSD in the non-elderly and elderly. Categorical sociodemographic and clinical variables were analyzed by chi-square test. Binary logistic regressions were performed using SSD (yes/no) as the dependent variable, adjusting for gender, educational level, marital status, and antipsychotic intake. Odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence interval (95%CI) values, and significance values (P-values) were reported in tabular form and forest plots. The number of risk factors for each participant was calculated to assess the association between the number of risk factors and SSD prevalence. Subgroup analysis by gender in the elderly group was also conducted.

Fisher’s exact test was used instead of the chi-square test only when one or more expectations for each cell of the 2-by-2 tables was below 5. A significance level was set at a p-value < 0.05 (two-tailed). Missing data were imputed with a multiple imputation approach. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 22 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results

Study population

Eleven thousand two hundred community dwellers people between March 2019 and June 2019 were approached, and the rejection rate was less than 1%. Then, all collected questionnaires were checked for completeness and quality by trained surveyors based on inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria. Based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, 9020 subjects between 18 to 100 were included in this prospective multicenter registry, composed of 6814 elderly (age ≥ 60 years) and 2206 non-elderly participants (18–59 years). The baseline characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 1. The median age of elderly participants was 70 (interquartile range, 65- to 75-year-old), and the median age for non-elderly participants was 48 (interquartile range, 36- to 56-year-old). Elderly participants had a higher prevalence of physical diseases and a lower average educational level.

Prevalence and severity of SSD

Figure 1 shows the distributions of SSD of different severities in non-elderly and elderly groups. Across all participants, the prevalence of SSD in the elderly (42.8% mild and 20.4% moderate/severe) was higher than that in the non-elderly (33.3% mild and 12% moderate/severe). The percentage of moderate/severe SSD in the elderly was higher (20.4%) than in the non-elderly (12.0%). As shown in Fig. 2, binary logistic regression analyses revealed that the elderly have a higher chance of suffering from SSD after adjustment for comorbid physical diseases and other confounding factors (OR = 1.560; 95%CI: 1.399–1.739; p < 0.001). Furthermore, we calculated the prevalence of SSD separately for participants with (n = 1865) and without (n = 7155) depressive or anxiety disorders, and the prevalence of SSD in patients with combined depressive or anxiety disorders was 3.7 times higher than would be expected in the general population. In elderly participants with SSD, 96.7% exhibited accompanying depressive disorders, and 95.7% exhibited anxiety (shown in Fig. 1, last 2 panels). Elderly participants had a higher percentage of depressive or anxiety disorders compared to the non-elderly group, in addition to exhibiting more severe symptoms.

Odds ratios (OR) of SSD, depressive disorder, and anxiety disorder between non-elderly and elderly groups. The non-elderly group was set as the reference category (Ref. = 1). Gender, educational level, marital status, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardio/cerebrovascular disease, other diseases, and intake of antipsychotics were adjusted

Association of SSD with depressive and anxiety disorders

In our study, the rates of depressive disorder and anxiety disorders were 17.0% (n = 1535) and 11.2% (n = 1014). In the elderly, the prevalence of anxiety disorder was 10.9% (n = 741), compared to 12.4% (n = 273) in the non-elderly. For depressive disorders, these values were 16.8% (n = 1142) and 17.8% (n = 393), respectively. Supplementary Table S1 shows the distribution of depressive and anxiety disorders of different severity. After adjusting for confounding factors, elderly populations were less likely to have depressive disorders than non-elderly populations (OR = 0.789, 95%CI: 0.684–0.909; p = 0.001) and were also less likely to have anxiety disorders (OR = 0.749; 95%CI: 0.634–0.884; p = 0.001) (shown in Fig. 2).

Although the elderly was not prone to anxiety or depressive disorders, binary logistic regression analyses revealed that comorbid SSD increased the risk of depressive and anxiety disorders, even after adjustment for comorbid physical diseases and other confounding factors. Regardless of SSD severity, elderly adults with SSD were at a much higher risk for depressive disorders and anxiety disorders compared to non-elderly adults (shown in Fig. 3).

Association of sociodemographic and clinical predictors with SSD

Table 2 depicts baseline univariate analyses of elderly and non-elderly participants based on the presence of SSD. Older age, female sex, and changed marital status were significantly predictive of higher SSD rates in the elderly group (p < 0.05). Interestingly, educational level was found to be associated with SSD in the non-elderly, but not in the elderly. With regard to clinical characteristics, cardiac disease and cardiovascular risk factors were significantly associated with SSD in elderly participants (p < 0.05).

In order to identify risk factors likely to independently predict SSD, the indices in Table 2 were used as input for multivariate analyses (shown in Fig. 4). Older age, female sex, diabetes mellitus, CV disease, hypertension were predictive risk factors of SSD in the elderly group after adjustment for confounding factors. Consideration of age‐related differences revealed that participants between 70–79 years old were 1.193 times more likely to have SSD compared to those between 60–69 years old (95%CI: 1.066–1.335; p = 0.002). Similarly, participants over 80 years of age were 1.291 times more likely to have SSD (95%CI: 1.093–1.525; p = 0.003). The risk of SSD was 1.566 times higher in elderly females compared to elderly males (95%CI: 1.406–1.744; p < 0.001).

To explore the influence of risk factors on SSD, the relationship between SSD prevalence and the number of risk factors is shown in Fig. 5. Elderly participants with no risk factors had an SSD prevalence of 47.1% (n = 338), and additional risk factors (up to four) were associated with SSD rates of 55.6% (n = 1357), 65.1% (n = 1400), 78.8%(n = 857) and 84.5% (n = 355). For non-elderly participants, respective SSD rates by number of patient risk factors were 27.0% (n = 131), 45.7% (n = 584), 60.8% (n = 203), 71.4% (n = 65) and 88.9% (n = 16). An elevated number of risk factors corresponded with a higher likelihood of SSD. The prevalence of SSD in the elderly was 1.554 times higher than that of the non-elderly group when controlling for the number of risk factors (95%CI: 1.394–1.733; p < 0.001). Notably, when the number of risk factors reached four, SSD prevalence in the non-elderly surpassed that observed in the elderly (shown in Fig. 5).

Discussion

This study was conducted across community health service institutions with majority-elderly participant populations. To our knowledge, our study is the first prospective cross-sectional study focusing on the clinical characteristics of SSD in elderly and non-elderly groups. This study reveals that the prevalence of SSD in the elderly in China is higher than that in non-elderly populations, and SSD severity tends to worsen with age. Additionally, comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders among the elderly was more closely related to the prevalence and severity of SSD. Finally, we found that female sex and the existence of physical diseases are associated with higher SSD prevalence (shown in Fig. 6).

Higher prevalence of SSD among the elderly

The high prevalence of SSD has many detrimental impacts on the elderly. Firstly, somatic symptoms and related disorders are associated with an increased risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, with an estimated 24–34% of participants disclosing current active suicidal ideation and 13–67% of participants disclosing a prior suicide attempt [24]. SSD could heavily impact the lifestyles of elderly patients, decreasing exercising ability and leading to the occurrence of sarcopenia [25]. The psychosocial distress brought by SSD can sometimes even cause serious organic diseases, such as myocardial infarction [26].

Shanghai was selected as the population of interest for this study because its life expectancy is 7 years higher than the national average [27, 28]. Shanghai has a large elderly population in which SSD characteristics can easily be explored. Unlike a previous study by Dehoust et al. [18], which focused only on the elderly, our study sought to identify differences between the elderly and the non-elderly populations. Of note, the prevalence of SSD detected in our study is higher than those reported by other studies [18, 29]. This may be due to the different criteria employed for SSD assessment. SSD from Hilderink study was diagnosed based on DSM-IV. Our questionnaire (SSS-CN), is based on DSM-5. The diagnostic criteria of SSD in the DSM-5 are less restrictive compared with those defined by the DSM-IV. The DSM-5 focuses more on physical symptoms, as well as on excessive thoughts, emotions, and/or behaviors brought on by them, which may result in a higher diagnosis rate for SSD.

Compared with non-elderly participants, we found that the severity of SSD was greater in elderly participants, and the condition became more severe with aging. Several reasons may account for these observations. First, elderly participants typically had more physical diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, and CV disease, that can induce somatic symptoms. However, Chinese elders tend to have a sense of shame in expressing mental discomfort, leading these experienced to be transduced into the form of bodily discomfort [30]. Second, biologically, dopamine levels decline by around 10% with each additional decade of life, and this reduction is associated with declined mental performance [31]. Serotonin levels also fall with increasing age and may be implicated in the regulation of synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis [32]. These aging-associated changes in neuro-endocrine secretion provide a biological explanation for the high prevalence of SSD in the elderly. Finally, the lack of estrogen in elderly women may increase the occurrence of SSD, as a recent study has suggested that estrogen supplementation can increase dopaminergic responsivity [33] and help improve encephalopathy [34].

Comorbidity of SSD with depressive and anxiety disorders

Comorbidity of SSD with depressive and anxiety disorders is expected [35,36,37]. In our study, we identified more SSD patients with depressive or anxiety disorders among the elderly, and the degree of SSD in these patients tended to be more severe than in their non-elderly counterparts. De Vroege et al. found that comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders occurred frequently within patients suffering from SSD (75.1% and 65.7%, respectively), which are much higher than that of our results. This could be due to the population difference. In De Vroege’s study [38], consecutive patients suffering from somatic symptoms and related disorders were enrolled. Patients were aware of their illnesses, more willing to express their psychological discomfort, resulting in higher comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders. Our study enrolled community-dwelling people, most of which hadn’t been previously diagnosed with SSD or other mental illnesses. They may not be willing to express their psychological discomfort.

Bernd et al. previously demonstrated that the contribution of commonalities underlying depressive disorder, anxiety disorder and somatization to functional impairment substantially exceeded the contributions of their independent parts [39]. However, no literature existed focusing on these comorbidities among the elderly. Our findings, therefore, fill a critical gap in this field. Recognizing the characteristics of physical and psychological problems found in elderly populations is critical for the future development of pharmaceutical and psychological interventions with appropriate intensity and timing.

Prevalence and number of risk factors

As expected, SSD occurrence was positively correlated with the number of risk factors, and prevalence was higher in the elderly (shown in Fig. 5). Intriguingly, when the number of risk factors reached four, SSD rates were higher in non-elderly participants. We propose two potential explanations for this phenomenon. Firstly, the number of non-elderly participants with ≥ 4 risk factors (n = 18) was far smaller than the number of elderly participants meeting the same criteria (n = 420), a potential source of bias. Secondly, non-elderly participants suffering from many (≥ 4) physical diseases may exhibit relatively higher stress levels.

Implications for early intervention of SSD

Regarding the treatment of SSD, neurocognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is of choice [40, 41]. However, De Vroege et al. reported high frequency of CBT dropout in patients with SSD and CBT has a limited effect [38]. Our findings provided rationales for the early detection and timely intervention in elderly patients. We found that older females with several comorbid physical diseases were vulnerable subjects. Regular screenings are suggested to be performed on those people. Proper interventions, such as raising social awareness of somatization disorder, involving elderly in more community activities are the possible approaches.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the clinical characteristics of SSD in elderly and non-elderly with the largest population. The relevant demographic, clinical features, and risk factors of the elderly with SSD are emphasized. We believe that our findings could provide a reference to economically developed regions in China in dealing with SSD in the elderly and prepare for the more severe aging in the future.

Our study also has several limitations. First, although our study represents the largest elderly and non-elderly population for which SSD has been studied to date, it is, nevertheless, a cross-sectional study for the elderly. No information was obtained about disorder progression or treatment requirements. Secondly, participants in our study were all enrolled from Shanghai, a city with better medical care, better education [27, 28] and more social stress than most other cities. Further research will be required to determine whether our findings can be generalized nationwide.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that, compared to the non-elderly, the elderly have a higher prevalence of SSD and exhibit more severe comorbidities with physical and psychological problems. Older females with several comorbid physical diseases were identified as an extremely vulnerable group; attention should be given to screening these outpatients.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from Yongxia Qiao upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SSD:

-

Somatic Symptom Disorder

- SSS-CN:

-

Somatic Symptom Scale-China

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7

References

Lim LL, Chang W, Yu X, Chiu H, Chong MY, Kua EH. Depression in Chinese elderly populations. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2011;3(2):46–53.

Population, surface area and density. In: UN data, a world of information. 2021. http://data.un.org. Accessed 15 Jun 2021.

The Seventh National Popualtion Census. In: National Bureau of Statistics. 2021. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202105/t20210510_1817181.html. Accessed 11 May 2021.

World Health Statistics 2021: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. In: World Health Organization. 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/342703/9789240027053-eng.pdf. Accessed 2021.

Ageing and health. In: World Health Organization. 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health. Accessed 4 Oct 2021.

White Paper on Mental Health of Chinese Urban Residents. In: Population Health Data Archive. 2019. https://www.ncmi.cn/phda/dataDetails.do?id=CSTR:A0006.23.A000A.202001.000576. Accessed 26 Dec 2019.

Noale M, Limongi F, Maggi S. Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Diseases in the Elderly. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1216:29–38.

Bansal N, Dhaliwal R, Weinstock RS. Management of diabetes in the elderly. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99(2):351–77.

Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368(9540):1005–11.

Alexopoulos GS. Depression in the elderly. Lancet. 2005;365(9475):1961–70.

Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(3):249–65.

Mitchell PB, Harvey SB. Depression and the older medical patient–when and how to intervene. Maturitas. 2014;79(2):153–9.

Uchmanowicz I, Gobbens RJJ. The relationship between frailty, anxiety and depression, and health-related quality of life in elderly patients with heart failure. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:1595–600.

Bland RC, Newman SC, Orn H. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the elderly in Edmonton. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1988;338:57–63.

Hessel A, Geyer M, Gunzelmann T, Schumacher J, Brahler E. Somatoform complaints in elderly of Germany. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2003;36(4):287–96.

Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD Jr, Rae DS, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, George LK, Karno M, Locke BZ. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States. Based on five Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(11):977–86.

Leiknes KA, Finset A, Moum T, Sandanger I. Current somatoform disorders in Norway: prevalence, risk factors and comorbidity with anxiety, depression and musculoskeletal disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(9):698–710.

Dehoust MC, Schulz H, Harter M, Volkert J, Sehner S, Drabik A, Wegscheider K, Canuto A, Weber K, Crawford M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of somatoform disorders in the elderly: Results of a European study. Int J Meth Psych Res. 2017;26(1):e1550.

Jiang M, Zhang W, Su X, Gao C, Chen B, Feng Z, Mao J, Pu J. Identifying and measuring the severity of somatic symptom disorder using the Self-reported Somatic Symptom Scale-China (SSS-CN): a research protocol for a diagnostic study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e024290.

Zhuang Q, Mao J, Li C, He B. Developing of somatic self-rating scale and its reliability and validity. Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci. 2010;09:847–9.

Zhuang Q, Mao J-I, He B. Developing of somatic self-rating scale and its reliability and validity. Chin J Behav Med Brain Science. 2010;19:847–9.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7.

Torres ME, Lowe B, Schmitz S, Pienta JN, Van Der Feltz-Cornelis C, Fiedorowicz JG. Suicide and suicidality in somatic symptom and related disorders: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2021;140:110290.

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA. Sarcopenia. Lancet. 2019;393(10191):2636–46.

Pedersen LR, Frestad D, Michelsen MM, Mygind ND, Rasmusen H, Suhrs HE, Prescott E. Risk Factors for Myocardial Infarction in Women and Men: A Review of the Current Literature. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(25):3835–52.

Shanghai Statistical Yearbook 2020. In: Shanghai Bureau of Statistics. 2021. http://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/20210303/2abf188275224739bd5bce9bf128aca8.html. Accessed 2021.

China Statistical Yearbook 2020. In: National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2021. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2020/indexch.htm. Accessed 2021.

Hilderink PH, Collard R, Rosmalen JG, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of somatoform disorders and medically unexplained symptoms in old age populations in comparison with younger age groups: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(1):151–6.

Kurlansik SL, Maffei MS. Somatic Symptom Disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(1):49–54.

Mukherjee J, Christian BT, Dunigan KA, Shi B, Narayanan TK, Satter M, Mantil J. Brain imaging of 18F-fallypride in normal volunteers: blood analysis, distribution, test-retest studies, and preliminary assessment of sensitivity to aging effects on dopamine D-2/D-3 receptors. Synapse. 2002;46(3):170–88.

Mattson MP, Maudsley S, Martin B. BDNF and 5-HT: a dynamic duo in age-related neuronal plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27(10):589–94.

Craig MC, Cutter WJ, Wickham H, van Amelsvoort TA, Rymer J, Whitehead M, Murphy DG. Effect of long-term estrogen therapy on dopaminergic responsivity in post-menopausal women–a preliminary study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(10):1309–16.

Tan ZS, Seshadri S, Beiser A, Zhang Y, Felson D, Hannan MT, Au R, Wolf PA, Kiel DP. Bone mineral density and the risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(1):107–11.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Linzer M, Hahn SR, deGruy FV 3rd, Brody D. Physical symptoms in primary care Predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(9):774–9.

Kroenke K, Jackson JL, Chamberlin J. Depressive and anxiety disorders in patients presenting with physical complaints: clinical predictors and outcome. Am J Med. 1997;103(5):339–47.

Wang J, Guo WJ, Mo LL, Luo SX, Yu JY, Dong ZQ, Liu Y, Huang MJ, Wang Y, Chen L, et al. Prevalence and strong association of high somatic symptom severity with depression and anxiety in a Chinese inpatient population. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2017;9(4):e12282.

de Vroege L, Timmermans A, Kop WJ, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. Neurocognitive dysfunctioning and the impact of comorbid depression and anxiety in patients with somatic symptom and related disorders: a cross-sectional clinical study. Psychol Med. 2018;48(11):1803–13.

Lowe B, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Mussell M, Schellberg D, Kroenke K. Depression, anxiety and somatization in primary care: syndrome overlap and functional impairment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(3):191–9.

Henningsen P, Zipfel S, Sattel H, Creed F. Management of Functional Somatic Syndromes and Bodily Distress. Psychother Psychosom. 2018;87(1):12–31.

van Dessel N, den Boeft M, van der Wouden JC, Kleinstauber M, Leone SS, Terluin B, Numans ME, van der Horst HE, van Marwijk H. Non-pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders and medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD011142.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the people who participated in this study and the staff in the communities who helped us collect the questionnaires.

Statements of ethics

All participants provided their written informed consent. The study is compliant with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki guidelines.

Funding

This study received funding support from the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC1312802); National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A20341,81971570 and 81930007); Shanghai Outstanding Academic Leaders Program (18XD1402400); National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (81625002); Program of Shanghai Academic/Technology Leader (21XD1432100) and Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (20Y11910500); Clinical Research Plan of SHDC (SHDC2020CR2025B); Shanghai Jiaotong University (YG2019ZDA12); University of Shanghai for Science and Technology (10–20-302–425) and Shanghai Jiao Tong University Public Health School Local High-level University Achievement-oriented Top-notch Cultivation Programme for Undergraduate Students (17ZYGW30). The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yani Wu and Zhengyu Tao, data analysis, interpretation of results, manuscript drafting and revise, approval of the final version of the manuscript; Meng Jiang, Yongxia Qiao, Jialiang Mao and Jun Pu, study concept and design, study supervision, drafting, revision, approval of the final version of the manuscript; Yezi Chai, Qiming Liu, Qifan Lu, Hongmei Zhou and Shiguang Li, data acquisition. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Amsterdam and registered on Clinical Trials Register (clinicaltrials.gov; NCT04815863, registered on 06/12/2020). Informed consents to participate in the study have been obtained from participants(or their parent or legal guardian in the case of children under 16).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts with any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Tao, Z., Qiao, Y. et al. Prevalence and characteristics of somatic symptom disorder in the elderly in a community-based population: a large-scale cross-sectional study in China. BMC Psychiatry 22, 257 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03907-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03907-1