Abstract

Background

To examine the relationship between the main caregiver during the “doing-the-month” (a traditional Chinese practice which a mother is confined at home for 1 month after giving birth) and the risk of postpartum depression (PPD) in postnatal women.

Methods

Participants were postnatal women stayed in hospital and women who attended the hospital for postpartum examination, at 14–60 days after delivery from November 1, 2013 to December 30, 2013. Postpartum depression status was assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Univariate and multivariable logistic regressions were used to identify the associations between the main caregiver during “doing-the-month” and the risk of PPD in postnatal women.

Results

One thousand three hundred twenty-five postnatal women with a mean (SD) age of 28 (4.58) years were included in the analyses. The median score (IQR) of PPD was 6.0 (2, 10) and the prevalence of PPD was 27%. Of these postnatal women, 44.5% were cared by their mother-in-law in the first month after delivery, 36.3% cared by own mother, 11.1% by “yuesao” or “maternity matron” and 8.1% by other relatives. No association was found between the main caregivers and the risk of PPD after multiple adjustments.

Conclusions

Although no association between the main caregivers and the risk of PPD during doing-the-month was identified, considering the increasing prevalence of PPD in Chinese women, and the contradictions between traditional culture and latest scientific evidence for some of the doing-the-month practices, public health interventions aim to increase the awareness of PPD among caregivers and family members are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a debilitating but treatable mental disorder that occurs after childbirth [1]. Symptoms of PPD include sleep disturbance, anxiety, irritability, feeling of overwhelmed and obsessional preoccupation with the baby’s health and feeding [1]. Suicide intention and harm to baby have also been reported [2]. PPD affects one in nine new mothers after childbirth, with prevalence ranging from 10 to 15% worldwide, and this is even higher in low- and middle- income countries [2]. In China, the prevalence of PPD was 15.5% [3].

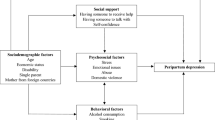

Past history of anxiety and untreated depression during pregnancy is the strongest risk factor of PPD [4]. In addition to reduced level of reproductive hormones, social determinants including social-economic levels, marital status and other factors such as sleep deprivation, infant’s sex and being primiparous were also well-recognised risk factors associated with PPD [5,6,7]. Moreover, social support is the key factor involved at the onset of depression and anxiety disorders [3]. Lack of support from spouse or family, and unsatisfactory marital relationship are also related to increased risk of PPD [3]. The availability and perception of social support might also be related to the development of PPD [8].

In China, “zuoyuezi”, or ‘doing-the-month’, a traditional practice for postpartum care, which mothers stay at home for a month immediately after childbirth, is a form of social support for the mothers in Chinese society [8, 9]. According to the theory of Traditional Chinese Medicine, there is an emphasis on balancing the yin and yang to maintain health. From the theory, the balance of yin and yang in prenatal women can be disrupted by labour. The rules of doing-the-month require the new mother to stay at home, and to avoid any physical labour, and anything cold for 1 month, which are believed to play important roles in regaining the balance of yin and yang, and to avoid unwell and misfortune [10].

Previous studies suggested that the traditional practice may prevent PPD in postnatal women, which may be due to the social supports and networks provided to the mothers during doing-the-month [11, 12]. The caregivers, who assist domestic duties to maintain the daily life of new mothers during doing-the-month, are often the women’s mother, mother-in-law, yuesao (a maternity matron who specializes in caring for mother and newborn infant) and/or family relatives [3]. Previous studies showed that postpartum care provided by women’s own mother exhibited fewer depressive symptoms. In contrast, mother-in-law as the main caregiver was a risk factor for PPD [3]. In many Asian countries, conflict between daughter- and mother-in-law is an essential cause of household distress [13]. A population-based study in Hong Kong showed that conflict with mother-in-law independently predicted the occurrence of PPD [14]. Power of decision-making at home and increased social support have been considered as the most important factors to promote women’s reproductive health [15]. However, caregiver’s identity was not found as an important risk factor of PPD in previous studies. In contrast, mother’s education, socioeconomic status, multiparity, history of depression, pregestational diabetes and negative birth experience were significantly associated with PPD [16, 17]. A study showed that caregiving was mediated by lower level of parental self-efficacy and lower marital satisfaction, and this study indicated that caregivers were not significant to PPD [18]. Therefore, the association between the role of caregivers and the risk of PPD for new mothers still remained unclear. In this study, we aim to investigate the relationship between the main caregivers of the mother during doing-the-month and compare the association between each type of caregiver and risk of PPD.

Methods

Participants

The present study used data from a pregnant and puerperal women mental health project conducted in Shenzhen City, China in 2013. The study was a single centre cross-sectional study carried out in the Shenzhen Maternity and Child Health Hospital. All postnatal women were recruited from the hospital where they delivered the baby and the hospital where postnatal women attended postpartum examination at 14–60 days after delivery from November 1, 2013 to December 30, 2013. A total of 1325 participants were included for the final analysis (n = 64 participants were excluded due to missing information regarding PPD).

Data collection

A study-specific questionnaire solicited information on demographic characteristics, obstetric information, pregnancy stress and socio-cultural factors was administered by nurses from the Shenzhen Maternity and Child Health Hospital. The study nurses were trained to follow the study protocol prior to study commencement. Ethics approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the Shenzhen Maternity and Child Health Hospital. A hard copy of the consent form was provided to each study participant.

Measurements

Assessment of covariates

The following demographic information was solicited: age, household registration (native or immigrant), monthly household income (categorized as <=10,000 Chinese yuan and > 10,000 Chinese yuan), living situation (only with husband, with puerperal women’s parents-in-law, with puerperal women’s parents), education level (categorised as junior high school or lower, high school or above), occupation (housewife or others) and medical insurance. Self-reported smoking and drinking behaviours were collected. The main caregiver of the mother in the first month after delivery (mother-in-law, mother, yuesao, other relatives) and obstetric information on parity (primiparous or parous), mode of delivery (vaginal or caesarean section), infant’s sex, and infant’s birth weight were also collected from the participants.

Stress during pregnancy

Stress during pregnancy was assessed by the Chinese version of the Pregnancy Stress Rating Scale (PSRS), which is a validated instrument among Chinese pregnant women [19]. The stress level during pregnancy was estimated using the sum of scores (ranging from 0 to 90), with a higher score indicating a higher stress level.

Social support

Social support was assessed by the Chinese version of the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) which has been validated in the Chinese population [19]. The sum of scores (ranging from 0 to 90) was used to indicate the level of social support received by participants, with a higher score indicating better social support.

Postpartum depression

PPD was assessed using the Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), which has been validated in Chinese puerperal women [20, 21]. The PPD was evaluated using the sum of scores (ranging from 0 to 30), with a higher score indicating a higher PPD level. The cut-off score to detect depression was defined as 9/10, which was found to be a reliable cut-off among Chinese women [21].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of study participants. Univariate logistic regression was performed to assess the association between putative factors and PPD risk. The risk factors included in the analyses were age, education level, household registration, household income, occupation, medical insurance, smoking, drinking, parity, mode of delivery, living situation, main caregiver of puerperal women, social support and stress during pregnancy. Variables with a p-value < 0.5 in the univariate analyses were then selected into multivariate logistic regression models. For multivariable logistic regression models, model 1 examined the association between the main caregiver of the mother and the risk of PPD with adjustment for demographic characteristics (household income and occupation), smoking and drinking. Model 2 additionally adjusted for parity, delivery mode and infant’s weight. The full model (model 3) further adjusted for living situation, social support and stress during pregnancy. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to investigate the association between the main caregiver of the mother and the trend of PPD score by performing multivariable linear regression models. Significant level was defined as p value < 0.5 and all analyses were performed using the SAS 9.4 (SAS institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

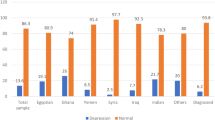

A total of 1325 puerperal women were included in the study. The mean (SD) age was 28 (4.58) years and the median score of PPD was 6.0 (2, 10). 26.6% of the study participants were identified with PPD. Women who had lower household income, smoked and drank regularly, primiparous, lived with parents-in-law, had less social support and with a higher stress level during pregnancy were more likely to suffer from PPD. Nearly half (44.5%) of the participants were cared by their mother-in-law during the doing-the-month, followed by 36.3% cared by their own mother, 11.1% by yuesao and 8.1% by other relatives. The characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 2 shows the results of the univariate analysis.

Table 3 shows the results of the multivariate analysis. Overall, compared to those whose main caregiver was her own mother, the odds of PPD compared to those whose main caregivers were yuesao, mother-in-law and other relatives were 1.16 (95% CI: 0.74–1.81), 1.23 (95% CI: 0.92–1.65) and 0.86 (95% CI: 0.51–1.47), respectively. The associations attenuated slightly after adjusting for covariates.

Table 4 shows the results of the sensitivity analysis. Compared with those whose main caregiver was their own mother, being cared by yuesao and mother-in-law had a 17.4% (p = 0.01) and 10.3% (p = 0.04) higher score of PPD after adjusting for covariates including household income, occupation, smoking, drinking, parity, delivery mode, infant’s weight, living situation, social support and stress during pregnancy. No differences in PPD occurrence in the new mother cared by her own mother and other relatives were found (p = 0.69).

Discussion

In this study population, around 27% of postpartum women were identified with PPD. The present study did not find a significant relationship between the main caregiver during doing-the-month and the presence of postpartum depression.

Doing-the-month is a set of traditional postpartum practices that has been practiced with a long history in China [10]. Although some of practices of doing-the-month have been abandoned, most of the Chinese women are brought up to believe that adherence to these practices of doing-the-month is important to their postnatal recovery and quality of life after childbirth [22]. Before yuesao became popular, the common practice of the doing-the-month came from the older generation including mother, mother-in-law or relatives (e.g. grandmother) [8]. Mother, mother-in-law and yuesao have similar perspectives and experiences in practicing doing-the-month. We speculated that different generations follow similar practices and mothers of newborns tend to follow these rules, as such, the person who provides doing-the-month guidance is not a contributor of postpartum depression. However, we note that this finding was not consistent with other studies from Beijing [3], Hong Kong [23] and Taiwan [24], which reported that the conflict between postnatal women and their mother-in-law during doing-the-month was a risk factor for postpartum depression. Indeed, conflict with mother-in-law is believed to be a significant contributor to depression and related events among married Chinese women [25, 26]. It was suggested that the conflict between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law may offset the potential benefits of family support [27]. Interestingly, we have previously reported that living with mother-in-law was associated with a higher risk of PPD in this population [28]. The findings in the same population reflected the conflicts between the traditional Chinese culture of obeying older generations, and modern values of independence and autonomy [23, 28].

Although a non-significant association between the main caregiver and the risk of PPD was identified in the present study, social support was found to be strongly associated with PPD in the univariate analysis. Consistently, a prospective cohort study conducted in China reported a reverse association between prenatal and postnatal social support and risk of PPD [29]. Meanwhile, another prospective study also found a lower perceived social support to be associated with PPD symptoms [30]. Other risk factors identified by the previous studies included smoking, drinking, stress during pregnancy, household income and parity were consistently found in our study [7, 31,32,33,34,35].

Regardless who the person is providing guidance or support for doing-the-month, evidence on doing-the-month itself and the development of PPD remains inconclusive [36]. Back in 1980s, PPD was not a major concern in the Chinese society because the prevalence was low (approximately 1.0–2.4%) [37, 38]. Doing-the-month practice was regarded as a protective factor for PPD because it provides social support to the mothers [39]. A recent study has reported that the prevalence of perinatal depression was 17–20% in China [40], or may be greater than 25%, depending on the criteria and timing for diagnosis, levels of urbanization and population characteristics [41, 42]. It is clear that the prevalence of PPD in China has increased in the past decades.

Apart from the increasing prevalence of PPD, advances in science and medicine also challenge the Chinese traditional culture, including some of the doing-the-month practice. For example, physical activity is not encouraged during doing-the-month [23]; in contrast, it has been demonstrated that physical activity may reduce the risk of excessive weight gain during pregnancy, gestational diabetes and PPD [43]. While who is the caregiver during doing-the-month has no association with the risk of PPD, caregiver’s role as an important component in social support in preventing new mother’s PPD, the increasing trend of PPD, as well as other mental health issues should not be overlooked.

The strengths of the current study included large sample size, and there was ample information on other potential risk factors of postpartum depression. This allows the inclusion of possible confounders in the statistical analysis to produce stable results.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, due to the cross-sectional design, no causal effect can be concluded from our findings. Secondly, participants were drawn from single study-center, which limited the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the current survey was conducted at 14–60 days after delivery, as such, the association with long-term outcome such as major depression, cannot be determined. Although the conflict with mother-in-law was not a significant factor of stress during doing-the-month in this population, it is not possible to estimate the long-term effect of these risk factors on advanced outcomes such as major depression and suicide events. Future studies investigating the relationship between traditional cultural factors and long-term mental health among Chinese women are needed. Residual confounding may also be possible, due to the lack of information on spousal relationship, autonomy or decision making and other unmeasured factors related to PPD.

In summary, our study does not support an association between the main caregivers of the mother and the risk of PPD during the doing-the-month. Considering the growing prevalence of PPD in Chinese women, and the contradictions between traditional culture and latest scientific evidence for some of the doing-the-month practices, public health interventions which aim to increase the awareness of PPD among caregivers and family members are warranted.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PPD:

-

Postpartum Depression

- PSRS:

-

Pregnancy Stress Rating Scale

- SSRS:

-

Social Support Rating Scale

- EPDS:

-

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- IQR:

-

Interquartile Range

References

Stewart DE, Vigod S. Postpartum depression. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2177–86. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1607649.

Anokye R, Acheampong E, Budu-Ainooson A, Obeng EI, Akwasi AG. Prevalence of postpartum depression and interventions utilized for its management. Ann General Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):18.

Wan EY, Moyer CA, Harlow SD, Fan Z, Jie Y, Yang H. Postpartum depression and traditional postpartum care in China: role of Zuoyuezi. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;104(3):209–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.10.016.

Wisner KL, Sit DK, McShea MC, Rizzo DM, Zoretich RA, Hughes CL, et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(5):490–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.87.

Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, Murphy J, Nieman L, Rubinow DR. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatr. 2000;157(6):924–30. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.924.

Beck CT. A meta-analysis of predictors of postpartum depression. Nurs Res. 1996;45(5):297–303. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199609000-00008.

Lu L, Duan Z, Wang Y, Wilson A, Yang Y, Zhu L, et al. Mental health outcomes among Chinese prenatal and postpartum women after the implementation of universal two-child policy. J Affect Disord. 2020;264:187–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.12.011.

Ding G, Tian Y, Yu J, Vinturache A. Cultural postpartum practices of ‘doing the month’ in China. Perspect Public Health. 2018;138(3):147–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913918763285.

Heh SS. Relationship between social support and postnatal depression. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2003;19(10):491–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70496-6.

Cheung NF, Mander R, Cheng L, Chen VY, Yang XQ, Qian HP, et al. ‘Zuoyuezi’ after caesarean in China: an interview survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(2):193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.04.003.

Pillsbury BL. “Doing the month”: confinement and convalescence of Chinese women after childbirth. Soc Sci Med B Med Anthropol. 1978;12:11–22.

Chu CM-Y. Reproductive health beliefs and practices of Chinese and Australian women: women’s research program, population studies center: National Taiwan University; 1993.

Fleck S. Culture and family: problems and therapy: LWW; 1993. p. 334.

Lee DT, Yip AS, Leung TY, Chung TK. Ethnoepidemiology of postnatal depression: prospective multivariate study of sociocultural risk factors in a Chinese population in Hong Kong. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184(1):34–40. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.184.1.34.

Sougou N, Bassoum O, Faye A, Leye M. Women’s autonomy in health decision-making and its effect on access to family planning services in Senegal in 2017: a propensity score analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–9.

Silverman ME, Reichenberg A, Savitz DA, Cnattingius S, Lichtenstein P, Hultman CM, et al. The risk factors for postpartum depression: a population-based study. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(2):178–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22597.

Righetti-Veltema M, Conne-Perréard E, Bousquet A, Manzano J. Risk factors and predictive signs of postpartum depression. J Affect Disord. 1998;49(3):167–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00110-9.

Kleinman C, Reizer A. Negative caregiving representations and postpartum depression: the mediating roles of parenting efficacy and relationship satisfaction. Health Care Women Int. 2018;39(1):79–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2017.1369080.

Chen C, Yu Y, Hwang K. Psychological stressors perceived by pregnant women during their third trimester. Formos J Public Health. 1983;10(1):88–98.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–6. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782.

Lee DT, Yip S, Chiu HF, Leung TY, Chan KP, Chau IO, et al. Detecting postnatal depression in Chinese women. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172(5):433–7. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.172.5.433.

Callister LC. Doing the month: Chinese postpartum practices. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2006;31(6):390. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005721-200611000-00013.

Leung SS, Arthur D, Martinson IM. Perceived stress and support of the Chinese postpartum ritual “doing the month”. Health Care Women Int. 2005;26(3):212–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330590917771.

Heh S-S, Coombes L, Bartlett H. The association between depressive symptoms and social support in Taiwanese women during the month. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004;41(5):573–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.01.003.

Zheng Y-P, Lin K-M. A nationwide study of stressful life events in mainland China. Psychosom Med. 1994;56(4):296–305. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199407000-00004.

Pearson V, Phillips MR, He F, Ji H. Attempted suicide among young rural women in the People’s Republic of China: possibilities for prevention. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32(4):359–69. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.32.4.359.22345.

Steinberg S. Childbearing research: a transcultural review. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43(12):1765–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00071-8.

Wang Y-Y, Li H, Wang Y-J, Wang H, Zhang Y-R, Gong L, et al. Living with parents or with parents-in-law and postpartum depression: a preliminary investigation in China. J Affect Disord. 2017;218:335–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.052.

Xie R-H, He G, Koszycki D, Walker M, Wen SW. Prenatal social support, postnatal social support, and postpartum depression. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(9):637–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.008.

Gan Y, Xiong R, Song J, Xiong X, Yu F, Gao W, et al. The effect of perceived social support during early pregnancy on depressive symptoms at 6 weeks postpartum: a prospective study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):232. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2188-2.

Davey HL, Tough SC, Adair CE, Benzies KM. Risk factors for sub-clinical and major postpartum depression among a community cohort of Canadian women. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(7):866–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-008-0314-8.

Dagher RK, Shenassa ED. Prenatal health behaviors and postpartum depression: is there an association? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(1):31–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-011-0252-0.

Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26(4):289–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006.

Schmied V, Johnson M, Naidoo N, Austin M-P, Matthey S, Kemp L, et al. Maternal mental health in Australia and New Zealand: a review of longitudinal studies. Women Birth. 2013;26(3):167–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2013.02.006.

Patel V, Araya R, De Lima M, Ludermir A, Todd C. Women, poverty and common mental disorders in four restructuring societies. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(11):1461–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00208-7.

Wong J, Fisher J. The role of traditional confinement practices in determining postpartum depression in women in Chinese cultures: a systematic review of the English language evidence. J Affect Disord. 2009;116(3):161–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.002.

Hwu HG, Yeh EK, Chang LY. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Taiwan defined by the Chinese diagnostic interview schedule. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;79(2):136–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb08581.x.

Chen C-N, Wong J, Lee N, Chan-Ho M-W, Lau JT-F, Fung M. The Shatin community mental health survey in Hong Kong: II. Major findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(2):125–33. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140051005.

Ding G, Niu L, Vinturache A, Zhang J, Lu M, Gao Y, et al. “Doing the month” and postpartum depression among Chinese women: a Shanghai prospective cohort study. Women Birth. 2020;33(2):e151–e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2019.04.004.

Mu T-Y, Li Y-H, Pan H-F, Zhang L, Zha D-H, Zhang C-L, et al. Postpartum depressive mood (PDM) among Chinese women: a meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2019;22(2):279–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0885-3.

Lee DT, Yip AS, Chiu HF, Leung TY, Chung TK. A psychiatric epidemiological study of postpartum Chinese women. Am J Psychiatr. 2001;158(2):220–6. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.220.

Deng A-W, Xiong R-B, Jiang T-T, Luo Y-P, Chen W-Z. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in a population-based sample of women in Tangxia community, Guangzhou. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7(3):244–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60030-4.

Dipietro L, Evenson KR, Bloodgood B, Sprow K, Troiano RP, Piercy KL, et al. Benefits of physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum: an umbrella review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(6):1292–302. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001941.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study has been funded by ‘Sanming’ Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (no. SZSM201811096), the Shenzhen Strategic Emerging Industry Development Special Fund, ZDYBH201900000007 and Young Talent Program of the Academician Fund, Fuwai Hospital Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Shenzhen, YS-2020-006.

Dr. Lei Si is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship (grant number GNT1139826).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yueyun Wang, Lin Zhou and Ke Peng conceived and designed the research. Yueyun Wang coordinated the recruitment of patients and the data collection. Wei Lin, Shixin Yuan and Bo Wu helped conducting the study. Ke Peng conducted the statistical analyses and interpreted the data. Ke Peng, Xiaoying Liu and Menglu Ouyang drafted the manuscript. Jessica Gong, Lei Si, Lin Zhou, Yu Shi, Jiani Chen, Yichong Li, Mingfan Sun, Yuanyuan Wang and Yueyun Wang commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Ethics approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the Shenzhen Maternity and Child Health Hospital. A hard copy of the consent form was provided to each study participant and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, K., Zhou, L., Liu, X. et al. Who is the main caregiver of the mother during the doing-the-month: is there an association with postpartum depression?. BMC Psychiatry 21, 270 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03203-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03203-4