Abstract

Background

Transgender, including gender diverse and non-binary people, henceforth referred to collectively as trans people, are a highly marginalised population with alarming rates of suicidal ideation, attempted suicide and self-harm. We aimed to understand the risk and protective factors of a lifetime history of attempted suicide in a community sample of Australian trans adults to guide better mental health support and suicide prevention strategies.

Methods

Using a non-probability snowball sampling approach, a total of 928 trans adults completed a cross-sectional online survey between September 2017 and January 2018. The survey assessed demographic data, mental health morbidity, a lifetime history of intentional self-harm and attempted suicide, experiences of discrimination, experiences of assault, access to gender affirming healthcare and access to trans peer support groups. Logistic regression was used to examine the risk or protective effect of participant characteristics on the odds of suicide.

Results

Of 928 participants, 73% self-reported a lifetime diagnosis of depression, 63% reported previous self-harm, and 43% had attempted suicide. Higher odds of reporting a lifetime history of suicide attempts were found in people who were; unemployed (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.54 (1.04, 2.28), p = 0.03), had a diagnosis of depression (aOR 3.43 (2.16, 5.46), p < 0.001), desired gender affirming surgery in the future (aOR 1.71 (1.134, 2.59), p = 0.01), had experienced physical assault (aOR 2.00 (1.37, 2.93), p < 0.001) or experienced institutional discrimination related to their trans status (aOR 1.59 (1.14, 2.22), p = 0.007).

Conclusion

Suicidality is associated with desiring gender affirming surgery in the future, gender based victimisation and institutionalised cissexism. Interventions to increase social inclusion, reduce transphobia and enable access to gender affirming care, particularly surgical interventions, are potential areas of intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Transgender, including gender diverse and non-binary (trans) people are a highly marginalised group in our community with alarmingly high rates of suicidality (ideation and non-fatal behaviours) and mental health morbidities [1,2,3]. High quality empirical evidence and data (such as from a census) describing the size of the trans population are limited, but a systematic review of studies published internationally from 2009 to 2019 found estimates ranged from 0.5 to 4.5% of the adult population [4]. Within an Australian-context, despite universal public health care and anti-discrimination laws at the State and Federal level, trans adults experience high levels of discrimination and are four times more likely than the general population to be diagnosed with depression, with over 40% self-reporting previous suicide attempts [5,6,7]. Various human rights challenges remain; in many Australian States and Territories, it is not possible to obtain legal gender recognition without first having gender affirmation surgery. Moreover, access to gender affirmation surgery is not covered by the national Medicare public health scheme and is cost prohibitive for many people.

Suicide attempts and suicide deaths occur due to a complex interaction between biological, psychological and psychosocial risk factors. This may include genetic predisposition to depression and anxiety [8, 9], minority stress and stressful life events, unemployment and financial stress [10,11,12], quality of support networks [13,14,15,16,17], discrimination, violence [18,19,20] and barriers to accessing healthcare and support services [21].

Trans-specific factors for suicidality is an under-researched area, but several risk and protective factors have been identified. Research has increasingly focused on how cissexism, or the belief that cisgender people are ‘normal’, ‘natural’ and ‘superior’ delimits opportunities for trans health and wellbeing [22]. Gender-based victimisation, including verbal abuse, peer rejection, threats of violence and physical assault has been well documented among trans adults [3, 23, 24]. Similarly, there is growing evidence of institutionalized cissexism, manifesting as heightened rates of trans unemployment, reduced access to housing, education and healthcare (including gender affirming healthcare), which contributes to diminished mental health and wellbeing by way of elevated feelings of shame, hopelessness and isolation [24,25,26,27,28,29]. Systemic barriers are associated with increased risk of housing instability, financial stress and violence [30].

Rather than focusing on the deleterious effects of cissexism, research has begun to illuminate factors that protect against suicidality and mental health comorbidities. For example, in trans people who wish to access hormones, being able to do so reduces mental distress, and improves quality of life [31, 32]. Similarly, trans adults who desire and are able to access gender affirming surgery report stronger mental health as compared to trans adults who cannot access surgeries [33]. Social support from family, friends and connection with the trans community and experiencing lower levels of structural discrimination are further protective factor against suicidality and suicide attempts [13,14,15,16,17].

Gender plays a role. In Australia, young cisgender men and those presumed to be men who live in non-metropolitan areas have the highest suicide rates and are less likely to seek assistance for depression or other mental health problems [34]. Data from many countries worldwide show that people presumed male have higher rates of suicide compared to people presumed female [35]. The precise reasons for the gender discrepancy are unclear, however possible explanations for higher rates of suicide in people presumed male include more violent, immediately lethal means of suicide, higher levels of suicidal intent and greater reticence to seek assistance from doctors for mental health support [36, 37].

In the general population, it is known that unemployment, physical assault and perceived discrimination increases risk for suicide ideation and suicide attempts [12, 38, 39]. We hypothesised that people who reported known risk factors for suicidal behaviour; residing in rural areas, unemployment, experienced difficulty accessing gender-affirming interventions, known history of depression or anxiety, had perceived discrimination and experiences of assault, would have a higher odds of reporting a history of suicide attempts. Given the lack of data describing risk or protective factors among Australian trans adults, this exploratory analysis aimed to assess factors associated with a lifetime history of attempted suicide in order to guide suicide prevention strategies and interventions.

Methods

This anonymous online survey of trans adults utilised a non-probability snowball sampling technique. Inclusion criteria for participants were assessed by a positive response to three screening questions: a) Australian residency; b) aged 18 years or older and c) self-identify as trans or gender diverse (defined as a ‘yes’ response to the question ‘Do you currently identify or have you previously identified as transgender or gender diverse?’). The inclusion of those who had previously identified as trans was intended to include those who identified as their affirmed gender (male, female or non-binary) rather than with the term transgender. Individuals were eligible to complete the survey on one occasion only and duplicate responses from the same Internet Protocol address were excluded. All included individuals had discordance between their assigned sex at birth and their gender identity. Survey questions were all optional. SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey Inc. San Mateo, California, USA) was used to collect responses to the survey between 1st September 2017 and 31st January 2018. Given that this was an anonymous survey, written informed consent was not possible and was waived by the institutional ethics committee; however, the survey preamble outlined that completion of the survey implied consent. The study was approved by the Austin Health Human Research and Ethics Committee (HREC/17/Austin/372).

Participants were asked a range of questions, with data pertaining to the health care needs and priorities of participants which are published elsewhere [7, 40]. The full version of the survey is available in the supplementary appendix at https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2020.0178 [7]. Participants were asked ‘Have you ever intentionally self-harmed?’ (response options of ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘prefer not to say’) and ‘Have you ever attempted suicide?’ with response options of ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘prefer not to say’. We specifically assessed if the following 10 factors were risk or protective factors for a positive (‘yes’) response for a lifetime history of attempted suicide.

-

1)

Location of residence (metropolitan or rural), which was determined by coding postcodes as per the Australia Standard Geographical Classification Remoteness Area (RA). Rural location of residence was classified as anyone living outside of a major city area corresponding to Remoteness Areas 2 to 5.

-

2)

Presumed gender at birth (male, female).

-

3)

Employment status (unemployed, compared to employed on full-time basis, part-time basis, home duties full time, student, retired, other)

-

4)

Access to gender affirming hormones. Participants were asked if they experienced any difficulty accessing gender affirming hormones with positive responses to the following multiple choice options: unable to find a doctor to prescribe; unable to afford costs of prescriptions; unable to afford cost of doctors’ appointments; or pathway to accessing hormones too difficult, compared to no difficulty accessing gender affirming hormones.

-

5)

Desire for gender affirming surgery in the future. Participants indicated whether they wanted gender affirming surgery someday, had already had surgery or did not want surgery, from the four options – bilateral mastectomy/chest reconstruction surgery, breast augmentation, bottom surgery, voice surgery. Those that desired at least one type of gender affirming surgery were compared with other groups that did not.

-

6)

Self-reported diagnosis of depression. Participants were asked if they had ever been medically diagnosed with depression (yes/no).

-

7)

Self-reported diagnosis of anxiety. Participants were asked if they had ever been medically diagnosed with anxiety (yes/no).

-

8)

Access to trans support groups. Participants were asked if they were a member of any trans support groups, including on social media (yes/no or unsure).

-

9)

Perceived discrimination from employment, housing, healthcare and/or government services. Participants were asked ‘Because of your trans status have you ever experienced any of the following (select all that apply)?’ with multiple choice options of ‘Discrimination from employment (i.e. lost a job or overlooked for a job)’, ‘Discrimination from housing (i.e. denied a rental application)’, ‘Discrimination from accessing healthcare’, and ‘Discrimination from government services (i.e. Centrelink)’, ‘Physical assault’, ‘Verbal abuse’, ‘Domestic violence’, and ‘None’. For the purposes of analyses positive responses to any of the four discrimination options (discrimination from employment, housing, accessing healthcare and government services) were combined to create one factor called ‘institutional discrimination’.

-

10)

Physical assault. Participants indicated whether they had ever experienced physical assault because of their trans status (yes/no).

Statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.6.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Participant characteristics are reported as frequency (percentage). Logistic regression was used to estimate the effects of the 10 factors listed above on the risk of attempted suicide. The 10 factors considered in the regression were selected prior to performing the analysis on the basis of previous known risk factors for suicidal behaviour. Results are reported as odds ratios (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Factors with low frequency categories were included in the regression, and a sensitivity analysis excluding low-frequency categories was performed where there is evidence of inflated standard errors and ORs. This is a complete case analysis with an alpha level of 5% (P < 0.05) to be considered statistically significant.

Results

There was a total of 964 responses to the survey, however, after excluding participants who did not fit the selection criteria and duplicate responses, there was a total of 928 eligible survey responses.

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Responses were received from all states and territories of Australia, with the majority residing in major city areas. The median age of participants was 28 years [interquartile range 23–39]. Sixty three percent of trans adults reported a lifetime history of intentional self-harm (n = 577), while 43% reporting ever having attempted suicide (n = 394). This compares to a lifetime prevalence of self-injury in the Australian general population of 8.1% and previous suicide attempts of 3.3% [41, 42]. From univariate analysis, there was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of suicide (p = 0.6) or self-harm (p = 0.08) between different states of residence. Access to and desire for gender affirming surgeries are presented in Table 2.

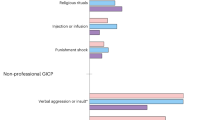

Variables which were associated with increased odds of a lifetime history of suicide attempts are shown in Table 3. Self-reported unemployment, desiring gender-affirming surgery in the future, depression, physical assault, and institutional discrimination were all associated with higher odds of reporting a previous suicide attempt. There was no association with anxiety, difficulty accessing hormones or location of residence (rural versus metropolitan), nor was access to trans support groups a protective factor. Being presumed male at birth was associated with lower odds of reporting a lifetime history of suicide attempts. Due to the low number of intersex individuals (n = 5), a valid odds ratio cannot be estimated and hence was not reported in Table 2. A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding those 5 participants and the results remains unchanged.

Discussion

This large community survey provides preliminary insight into the factors associated with suicidality in the Australian trans community. Being unemployed, reporting a diagnosis of depression, desiring gender affirming surgery, a history of physical assault and experiences of institutional discrimination were all factors associated with increased odds of a lifetime history of suicide attempts. Being presumed male at birth was associated with lower odds of suicide attempt.

While the self-reported suicide attempt rate of trans participants is 10-times higher than that reported for the general Australian population, this rate converges with data on Australian trans youth and similar cohort studies conducted in Euro-Western settings [6, 41,42,43]. This pattern of convergence suggests that health disparities and systemic social inequities are not confined to a specific developmental time frame nor geographic locality. Notably, we found intentional self-harm rates (63%) were even higher than the rate of suicide attempt, but previous evidence has shown that in the Australian population, self-harm can occur in the absence of suicidal thoughts, often used as a means of managing difficult emotions [42]. While beyond the scope of the current analysis, it may be that persistent social exclusion and acts of erasure result in elevated feelings of shame, hopelessness and isolation-factors associated with self-harm [24,25,26,27,28,29].

Due to widespread cissexism and transphobia, physical assault is an all-too-common experience within the trans community. It was reported by 21% of respondents and was associated with a 100% increase in the odds of a lifetime suicide attempt. Physical assault has consistently been associated with poor mental health outcomes and a higher risk of suicide [19, 20, 44]. Critically, being physically assaulted because of a perpetrator’s transphobic prejudice is associated with a higher probability of suicide attempt than a physical assault not attributed to prejudice, or experiencing institutional discrimination alone without assault [45].

Additionally, experiences of institutionalised discrimination were reported at a high frequency. In our study, this included discrimination while accessing healthcare (including gender affirming healthcare), in employment, housing, and accessing government services. In a US-based study of 6450 trans people, an extraordinary 90% reported experiencing harassment, mistreatment or discrimination in workplaces, housing and in healthcare settings due to prejudice related to their trans-status or took actions such as hiding their identity to mitigate risk [3]. Specifically, service denial in healthcare has a profound impact correlated with elevated rates of attempted suicide [21]. Social and institutional discrimination has been found to negatively impact trans people’s mental health and has been consistently demonstrated to be a risk factor for attempted suicide, underscoring the need for multi-level interventions to enable timely, rights-based and culturally safe access to gender affirming and general healthcare, end discrimination and protect the trans population across every domain of life [18, 29, 46, 47].

In addition to discrimination, unemployment was associated with a 54% higher odds of lifetime suicide attempt. The trans unemployment rate of 19% is three times higher than the general Australian population (5.5%) [48]. In general population studies, unemployment and financial precarity has been linked to suicidality, with the length of unemployment compounding the risk of suicide [10,11,12]. The impact of employment on mental and physical health, socioeconomic status and quality of life is profound [49, 50]. Perceived stress in everyday life is known to increase the risk of unemployment, yet unemployment and sustained economic hardship can also directly negatively affect physical, psychological and cognitive functioning [51,52,53,54]. Poverty arising from unemployment may additionally limit an individual’s ability to access gender-affirming healthcare, particularly gender-affirming surgery which is associated with large out-of-pocket costs [3, 55]. Notably, there are many potential barriers to employment for trans people such as persistent challenges being affirmed and respected by employers and colleagues using the correct name, gender and pronouns, to being terminated, looked over for promotions and facing discrimination and violence at work, to discrimination in basic housing and healthcare and the impact of mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety on an individual’s ability to seek or maintain employment [29, 56]. Moreover, 33% reported perceived discrimination from employment, and whilst it was not directly assessed in the survey questions, workplace environments that expose individuals to discrimination have been found elsewhere to impact on an individual’s mental health and ability to maintain employment [29].

Self-reported lifetime diagnoses of depression were high in our participants, and this was associated with an over 200% increased odds of reporting a lifetime suicide attempt. Similarly, a lifetime history of major depressive disorder has been significantly associated with increased risk of suicidal ideation and attempted suicide in trans people worldwide [8, 9]. Depression in trans people is multifaceted, and there are various contributing factors; including discrimination, disclosure, social support, access to gender affirming healthcare, substance use and socioeconomic factors [57]. As such, strategies to lower the high rates of depression will need to be multifaceted, supported by accessible, specific and safe mental health support services for trans individuals, and improved access to gender affirming healthcare [58].

Anxiety, which is highly prevalent in the trans community, was not significantly associated with lifetime suicide attempt after adjustment, suggesting that the association is influenced by other confounders, such as depression. This is inline with some general population studies that have found that anxiety disorder alone is not associated with suicidality [59].

We demonstrate that trangender individuals who desire gender affirming surgery in the future experience 71% increased odds of reporting a lifetime suicide attempt. This is likely related to a number of intrapersonal and interpersonal factors, and barriers to healthcare access. Those individuals who desire gender affirming surgery generally experience body and/or social dysphoria related to that part of their body, resulting in mental health distress. Gender affirming surgeries may result in significant body changes that increase the likelihood that trans individuals will be read and understood by others as their affirmed gender. Those who desire but are yet to access surgeries may experience higher rates of misgendering, discrimination and violence due to gender non-conformity or ambiguous appearance [3, 60], which in turn may have an impact on mental health.

Access to gender-affirming surgery has been shown to improve mental health and quality of life indicators for those who have undertaken a surgical intervention to affirm their gender. [5, 33, 61] In an Australian study regarding surgery experiences and satisfaction, depression was reported in 34% of those individuals who had undergone at least some form of gender-affirming surgery, compared to 51% in those who desired but had not undergone surgery. [33] Our findings concur with previous research that those who want surgery but have yet to access it, are at significantly increased risk of suicide.

Desire for gender affirming surgery in the future may also be related to healthcare access. One of the biggest barriers reported by trans individuals is a lack of access to healthcare due to the lack of healthcare professionals skilled in gender affirming healthcare [62]. Access to gender affirming surgery, in particular, poses significant barriers due to a lack of experienced surgeons, high cost, the lack of public funding and “gate-keeping” requirements, which can typically involve multiple, detailed assessments with two mental health professionals prior to surgery. Barriers to access, may therefore also contribute to mental health distress and suicality, as individuals are faced with long, complicated and often prohibitively expensive options for gender affirming surgeries.

Greater training, programs and clinical supervision for surgeons already conducting or wishing to conduct gender affirming surgery, along with full public funding for all gender-affirming surgeries is critical to address this healthcare gap in access to such medically necessary interventions.

Interestingly our findings show that trans women and non-binary participants presumed male at birth appeared to have a lower odds of suicide attempt and the converse is true for trans men and non-binary participants presumed female at birth. Whilst suicide deaths in the Australian population occur at higher rates in those recorded as male, there is a higher rate of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in those presumed female at birth [63]. Certainly studies assessing suicide attempts in the trans community have shown variable gender distributions and inferences are unclear [64].

In the Australian general population, the rates of suicide tend to increase with increasing rurality. This is commonly associated with several factors, including essential services such as healthcare and mental health support. [65, 66] This study however, showed no statistically significant difference in lifetime suicide attempt between trans people living in inner city areas and those living in regional and remote areas. Protective factors that might mitigate the expected association between rurality and suicidality include reasons for living, the individual’s resilience and ability to self-regulate suicidal thoughts and feelings, familial and social support and optimism. [67, 68] However, there is relatively little research directly examining protective factors in the trans population and the experience of trans individuals and communities in regional and remote areas, an effect termed the ‘metronormative’ bias of trans research. [69] Seminal qualitative research conducted in the USA illuminates how trans experiences of resilience in regional and rural places rests upon other social positions (e.g., race, queerness, disability and sexuality). [70]

Previous research suggests that a lack of social support is associated with higher odds of psychological distress and lifetime suicide attempts, and that social support from the trans community is a protective factor against suicidal ideation and suicide attempts [17, 71]. Contrary to those studies, our study indicates that there is no significant association between being part of a trans support group and suicide attempts. Notably, our survey did not ask about community connection which is different from being a member of a support group, nor did the survey assess other forms of social support, such as that from family and friends, which has been shown to be a protective factor [13, 14, 16, 68].

Not all trans people desire gender affirming hormones in their transition. However, for those people who do, the ability to access hormones reduces mental distress [31, 32]. The highest rates of depression in trans people are in those who want hormones but have yet to use them or are unable to access them [5]. Despite the strong link between depression and suicidality, this study found no significant difference in suicidality solely based on access to hormones. Given that there may be many confounding factors that impact mental health independently of hormone therapy, such as access to other gender affirming medical procedures and psychotherapy, as well as social support, it is difficult to determine the independent effects of hormone therapy on quality of life [32]. There is also evidence that any form of gender affirming transition is beneficial, such as social transition and social acceptance [67].

Limitations

There are multiple limitations to this online study utilising a non-probability snowball sampling approach. The online-based recruitment may explain the proportion of younger participants and the views of older trans people may not be accurately reflected. There may be self-selection bias and not all areas of Australia were represented equally as recruitment was not targeted. There was a predominance of respondents in South-Eastern states, which may be related to physical promotion of the study at one event in Victoria and New South Wales. However, distribution of respondents was similar to a previous 2013 Western Australian-based survey [5]. Depression, self-harm and suicide attempts were self-reported. Hence, it is not possible to confirm diagnosis or determine how individuals define their experiences (e.g. what constitutes self-harm versus a suicide attempt; diagnosis of clinical depression). We did not study completed suicide, however suicide attempts are a risk factor for suicide and reflect significant distress experienced. The survey was also designed to broadly explore healthcare and wellbeing in the trans community and as such, did not focus extensively on mental health and suicidality. This survey was, however, a platform for trans people in Australia to express their experiences and opinions anonymously and honestly. It provides valuable insight on the health needs and wellbeing of a marginalised community.

Conclusion

This large community survey highlights the high rates of attempted suicide, self-harm and depression in the trans community. Suicide attempts occur due to a complex interaction between socio-political, environmental, interpersonal and structural risk factors. Rather than suicidality perceived as inherent to the trans experience, trans people appear to exhibit higher rates of suicidality as a manifestation of social discrimination. Addressing these factors that contribute to suicidality and the mental health burden in the trans community must be made a priority. Dismantling barriers to gender affirming healthcare is paramount; as is tackling pervasive cissexism in order to reduce incidents of discrimination, stigmatization and violence. There is also an ongoing need to shift the discourse of the health and health needs of trans people away from a focus on risk and deficit, to align with a strength-based approach to illuminate factors that protect against suicidality and to promote resilience.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

09 November 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03491-w

References

Zucker KJ. Epidemiology of gender dysphoria and transgender identity. Sex Health. 2017;14(5):404–11.

Ahs JW, Dhejne C, Magnusson C, Dal H, Lundin A, Arver S, et al. Proportion of adults in the general population of Stockholm County who want gender-affirming medical treatment. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204606.

Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at every turn: a report of the national transgender discrimination survey. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2011.

Zhang Q, Goodman M, Adams N, Corneil T, Hashemi L, Kreukels B, et al. Epidemiological considerations in transgender health: a systematic review with focus on higher quality data. Int J Transgender Health. 2020;21(2):125–37.

Hyde Z, Doherty M, Tilley PJM, McCaul KA, Rooney R, Jancey J. The first Australian national trans mental health study: summary of results. Perth: Curtin University; 2014.

Strauss P, Cook A, Winter S, Watson V, Wright Toussaint D, Lin A. Associations between negative life experiences and the mental health of trans and gender diverse young people in Australia: findings from trans pathways. Psychol Med. 2020;50(5):808–17.

Bretherton I, Thrower E, Zwickl S, Wong A, Chetcuti D, Grossmann M, et al. The health and well-being of transgender Australians: a national community survey. LGBT Health. 2021;8(1):42–9.

Azeem R, Zubair UB, Jalil A, Kamal A, Nizami A, Minhas F. Prevalence of suicide ideation and its relationship with depression among transgender population. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2019;29(4):349–52.

Chen R, Zhu X, Wright L, Drescher J, Gao Y, Wu L, et al. Suicidal ideation and attempted suicide amongst Chinese transgender persons: national population study. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:1126–34.

Blakely TA, Collings SCD, Atkinson J. Unemployment and suicide. Evidence for a causal association? J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2003;57(8):594.

Classen TJ, Dunn RA. The effect of job loss and unemployment duration on suicide risk in the United States: a new look using mass-layoffs and unemployment duration. Health Econ. 2012;21(3):338–50.

Nordt C, Warnke I, Seifritz E, Kawohl W. Modelling suicide and unemployment: a longitudinal analysis covering 63 countries, 2000-11. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(3):239–45.

Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE. Reducing suicide: a national imperative. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2002.

Gutierrez PM, Osman A. Adolescent suicide. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press; 2008.

Moody C, Smith NG. Suicide protective factors among trans adults. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(5):739–52.

Ross-Reed DE, Reno J, Peñaloza L, Green D, FitzGerald CJJAH. Family, school, and peer support are associated with rates of violence victimization and self-harm among gender minority and cisgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(6):776–83.

Sherman AD, Clark KD, Robinson K, Noorani T, Poteat T. Trans* community connection, health, and wellbeing: a systematic review. LGBT Health. 2020;7(1):1–14.

Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Katz M. Attempted suicide among transgender persons: the influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. J Homosex. 2006;51(3):53–69.

Nuttbrock L, Hwahng S, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, Mason M, Macri M, et al. Psychiatric impact of gender-related abuse across the life course of male-to-female transgender persons. J Sex Res. 2010;47(1):12–23.

Rood BA, Puckett JA, Pantalone DW, Bradford JB. Predictors of suicidal ideation in a statewide sample of transgender individuals. LGBT Health. 2015;2(3):270–5.

Romanelli M, Lu W, Lindsey MA. Examining mechanisms and moderators of the relationship between discriminatory health care encounters and attempted suicide among U.S. transgender help-seekers. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2018;45(6):831–49.

Bauer GR, Hammond R, Travers R, Kaay M, Hohenadel KM, Boyce M. “I don't think this is theoretical; this is our lives”: how erasure impacts health care for transgender people. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20(5):348–61.

Couch MA, Pitts MK, Patel S, Mitchell AE, Mulcare H, Croy SL. TranZnation: a report on the health and wellbeing of transgender people in Australia and New Zealand. Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University; 2007.

Lombardi EL, Wilchins RA, Priesing D, Malouf D. Gender violence: transgender experiences with violence and discrimination. J Homosex. 2002;42(1):89–101.

Harper GW, Schneider M. Oppression and discrimination among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people and communities: a challenge for community psychology. Am J Community Psychol. 2003;31(3–4):243–52.

Rodriguez A, Agardh A, Asamoah BO. Self-reported discrimination in health-care settings based on recognizability as transgender: a cross-sectional study among transgender US citizens. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(4):973–85.

Mustanski B, Liu RT. A longitudinal study of predictors of suicide attempts among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(3):437–48.

Dean L, Meyer IH, Robinson K, Sell RL, Sember R, Silenzio VM, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: findings and concerns. J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc. 2000;4(3):102–51.

Bradford J, Reisner SL, Honnold JA, Xavier J. Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: results from the Virginia transgender health initiative study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1820–9.

Blosnich JR, Marsiglio MC, Dichter ME, Gao S, Gordon AJ, Shipherd JC, et al. Impact of social determinants of health on medical conditions among transgender veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(4):491–8.

Nguyen HB, Chavez AM, Lipner E, Hantsoo L, Kornfield SL, Davies RD, et al. Gender-affirming hormone use in transgender individuals: impact on behavioral health and cognition. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20(12):110.

White Hughto JM, Reisner SL. A systematic review of the effects of hormone therapy on psychological functioning and quality of life in transgender individuals. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):21–31.

Riggs DW, Coleman K, Due C. Healthcare experiences of gender diverse Australians: a mixed-methods, self-report survey. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):230.

Caldwell TM, Jorm AF, Dear KB. Suicide and mental health in rural, remote and metropolitan areas in Australia. Med J Aust. 2004;181(S7):S10–4.

Moller-Leimkuhler AM. The gender gap in suicide and premature death or: why are men so vulnerable? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;253(1):1–8.

Rich CL, Ricketts JE, Fowler RC, Young D. Some differences between men and women who commit suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(6):718–22.

Wang Y, Hunt K, Nazareth I, Freemantle N, Petersen I. Do men consult less than women? An analysis of routinely collected UK general practice data. BMJ Open. 2013;3(8):e003320.

Bryan CJ, McNaugton-Cassill M, Osman A, Hernandez AM. The associations of physical and sexual assault with suicide risk in nonclinical military and undergraduate samples. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2013;43(2):223–34.

Gomez J, Miranda R, Polanco L. Acculturative stress, perceived discrimination, and vulnerability to suicide attempts among emerging adults. J Youth Adolesc. 2011;40(11):1465–76.

Zwickl S, Wong A, Bretherton I, Rainier M, Chetcuti D, Zajac JD, et al. Health needs of trans and gender diverse adults in Australia: a qualitative analysis of a national community survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24):5088.

National survey of mental health and wellbeing: summary of results, cat. no. 4326.0, ‘Table 8–1: Prevalence of lifetime and 12-month suicidality’. In. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2007.

Martin G, Swannell SV, Hazell PL, Harrison JE, Taylor AW. Self-injury in Australia: a community survey. Med J Aust. 2010;193(9):506–10.

Klein A, Golub SA. Family rejection as a predictor of suicide attempts and substance misuse among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. LGBT health. 2016;3(3):193–9.

Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Katz M. Attempted suicide among transgender persons. J Homosex. 2006;51(3):53–69.

Barboza GE, Dominguez S, Chance E. Physical victimization, gender identity and suicide risk among transgender men and women. Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:385–90.

Kohlbrenner V, Deuba K, Karki DK, Marrone G. Perceived discrimination is an independent risk factor for suicidal ideation among sexual and gender minorities in Nepal. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159359.

Carter SP, Allred KM, Tucker RP, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Lehavot K. Discrimination and suicidal ideation among transgender veterans: the role of social support and connection. LGBT health. 2019;6(2):43–50.

Statistics ABo. Labour force, Australia, May 2018. 2018.

Doku DT, Acacio-Claro PJ, Koivusilta L, Rimpelä A. Health and socioeconomic circumstances over three generations as predictors of youth unemployment trajectories. Eur J Pub Health. 2019;29(3):517–23.

Norström F, Waenerlund A-K, Lindholm L, Nygren R, Sahlén K-G, Brydsten A. Does unemployment contribute to poorer health-related quality of life among Swedish adults? BMC Public Health. 2019;19:457.

Mæhlisen MH, Pasgaard AA, Mortensen RN, Vardinghus-Nielsen H, Torp-Pedersen C, Bøggild H. Perceived stress as a risk factor of unemployment: a register-based cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):728.

Linn MW, Sandifer R, Stein S. Effects of unemployment on mental and physical health. Am J Public Health. 1985;75(5):502–6.

van der Noordt M, H IJ, Droomers M, Proper KI. Health effects of employment: a systematic review of prospective studies. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71(10):730–6.

Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Shema SJ. Cumulative impact of sustained economic hardship on physical, cognitive, psychological, and social functioning. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(26):1889–95.

Adams NJ, Vincent B. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among transgender adults in relation to education, ethnicity, and income: a systematic review. Transgend Health. 2019;4(1):226–46.

Winter S, Davis-McCabe C, Russell C, Wilde D, Chu TH, Suparak P, et al. Denied work: an audit of employment discrimination on the basis of gender identity in Asia. Bangkok: Asia Pacific Transgender Network and United Nations Development Programme; 2018.

Khobzi Rotondi N. Depression in trans people: a review of the risk factors. Int J Transgend Health. 2012;13(3):104–16.

Snapshot of mental health and suicide prevention statistics for LGBTI people. In.: National LGBTI Health Alliance; 2020.

Sareen J, Houlahan T, Cox BJ, Asmundson GJG. Anxiety disorders associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the national comorbidity survey. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193(7):450–4.

Brumbaugh-Johnson SM, Hull KE. Coming out as transgender: navigating the social implications of a transgender identity. J Homosex. 2019;66(8):1148–77.

Ainsworth TA, Spiegel JH. Quality of life of individuals with and without facial feminization surgery or gender reassignment surgery. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(7):1019–24.

Safer JD, Coleman E, Feldman J, Garofalo R, Hembree W, Radix A, et al. Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diab Obes. 2016;23(2):168–71.

Causes of Death, Australia, 2018 (cat. no. 3303.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2019.

Kuper LE, Adams N, Mustanski BS. Exploring cross-sectional predictors of suicide ideation, attempt, and risk in a large online sample of transgender and gender nonconforming youth and young adults. LGBT Health. 2018;5(7):391–400.

Suicide in rural Australia. Canberra; National Rural Health Alliance; 2009.

Judd F, Cooper A-M, Fraser C, Davis J. Rural suicide—people or place effects? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(3):208–16.

Cogan CM, Scholl JA, Cole HE, Davis JL. The moderating role of community resiliency on suicide risk in the transgender population. J LGBT Issues Couns. 2020;14(1):2–17.

Bauer GR, Scheim AI, Pyne J, Travers R, Hammond R. Intervenable factors associated with suicide risk in transgender persons: a respondent driven sampling study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):525.

Halberstam J. In a queer time and place: transgender bodies, subcultural lives. New York: NYU Press; 2005.

Abelson MJ. Men in place: trans masculinity, race, and sexuality in America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 2019.

Turban JL, Beckwith N, Reisner SL, Keuroghlian AS. Association between recalled exposure to gender identity conversion efforts and psychological distress and suicide attempts among transgender adults. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(1):68–76.

Funding

Ada Cheung is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Early Career Fellowship (Grant number: 1143333) and received research support for this project from the Endocrine Society of Australia, Austin Medical Research Foundation, RACP Foundation and Viertel Charitable Foundation. Ingrid Bretherton is supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z., A.F.Q.W., I.B., E.D., J.D.Z., and A.S.C.; Methodology, S.Z., A.F.Q.W., E.D., I.B., T.C., and A.S.C.;; Investigation, S.Z., A.F.Q.W., and I.B.; Formal Analysis, S.Z., A.F.Q.W., S.Y.L., P.S.F.Y., and A.S.C.; Writing – Original Draft, S.Z., A.F.Q.W., and A.S.C.; Writing – Review & Editing, S.Z., A.F.Q.W., E.D., S.Y.L., I.B., T.C., J.D.Z., P.S.F.Y., and A.S.C.; Funding Acquisition, A.S.C.; Supervision, A.S.C. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Austin Health Human Research and Ethics Committee (HREC/17/Austin/372). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Given that this was an anonymous survey, written informed consent was not possible and was waived by the institutional ethics committee; however, the survey preamble outlined that completion of the survey implied consent.

Competing interests

No competing financial interests exist. No conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: the clarifications, additional information, and changes in the text and tables have been updated.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zwickl, S., Wong, A.F.Q., Dowers, E. et al. Factors associated with suicide attempts among Australian transgender adults. BMC Psychiatry 21, 81 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03084-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03084-7