Abstract

Background

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a considerable public health concern. In spite of evidence-based treatments for MDD, many patients do not improve and relapse is common. Therefore, improving treatment outcomes is much needed and adjunct exercise treatment may have great potential. Exercise was shown to be effective as monotherapy for depression and as augmentation strategy, with evidence for increasing neuroplasticity. Data on the cost-effectiveness and the long-term effects of adjunct exercise treatment are missing. Similarly, the cognitive pathways toward remission are not well understood.

Methods

The present study is designed as a multicenter randomized superiority trial in two parallel groups with follow-up assessments up to 15 months. Currently depressed outpatients (N = 120) are randomized to guideline concordant Standard Care (gcSC) alone or gcSC with adjunct exercise treatment for 12 weeks. Randomization is stratified by gender and setting, using a four, six, and eight block design. Exercise treatment is offered in accordance with the NICE guidelines and empirical evidence, consisting of one supervised and two at-home exercise sessions per week at moderate intensity. We expect that gcSC with adjunct exercise treatment is more (cost-)effective in decreasing depressive symptoms compared to gcSC alone. Moreover, we will investigate the effect of adjunct exercise treatment on other health-related outcomes (i.e. functioning, fitness, physical activity, health-related quality of life, and motivation and energy). In addition, the mechanisms of change will be studied by exploring any change in rumination, self-esteem, and memory bias as possible mediators between exercise treatment and depression outcomes.

Discussion

The present trial aims to inform the scientific and clinical community about the (cost-)effectiveness and psychosocial mechanisms of change of adjunct exercise treatment when implemented in the mental health service setting. Results of the present study may improve treatment outcomes in MDD and facilitate implementation of prescriptive exercise treatment in outpatient settings.

Trial registration

This trial is registered within the Netherlands Trial Register (code: NL8432, date: 6th March, 2020).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Around 268 million people worldwide suffer from major depressive disorder (MDD), indicating that depression is a highly prevalent condition [1]. Those affected experience persistent feelings of sadness and a loss of pleasure or interest in activities. Physical comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases [2] and metabolic risk factors [3] are common too and MDD is one of the leading causes of disability and mortality worldwide [4]. Moreover, MDD is not just a burden for the individual, but also impacting the society as a whole. For example, incremental costs of patients suffering from MDD have been estimated at $210 billion in the United States [5]. Given the high prevalence and personal and societal burden, improving treatment of MDD is essential.

Standard treatment options consist of antidepressant medication and/or psychological interventions such as cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT). While those treatment options are overall effective and generally of comparable effectiveness [6], approximately 40% of depressed patients do not respond adequately to treatment [7, 8] and recurrence rates are high (i.e. greater than 60%) [9]. Importantly, most treatment options have disadvantages, including high costs and unpleasant side effects. Moreover, they have no direct effect on somatic risk factors and comorbid somatic diseases. Hence, there is a need for new (combination) treatments.

One such treatment option is physical exercise. Exercise has been shown to be effective as monotherapy [10,11,12,13] and as augmentation strategy for antidepressant medication and psychological treatment [14,15,16,17,18,19]. Previous research showed that especially the combination of exercise and another treatment (i.e. antidepressants or psychological intervention) is effective in reducing depressive symptoms [19, 20]. Further, exercise may prevent relapse [21], benefits physical comorbidities [22], and is - unlike other treatments for depression - inexpensive, universally accessible, and shows favourable tolerability [23]. Hence, implementing an evidence-based exercise treatment module within depression standard care seems feasible and is hypothesized to be (cost-)effective. Nonetheless, the long-term effects of exercise treatment are largely unexplored [24, 25]. Therefore, the first aim of the present study is to investigate the (cost-)effectiveness of exercise as adjunct treatment for depression within the mental health system, including examination of the long-term effects up to 15 months.

Furthermore, exercise might not only improve depression but might benefit other health outcomes as well. For instance, regular exercise leads to improved fitness [26, 27] and several studies showed that exercise programs increase overall physical activity levels [28,29,30]. Similarly, exercise interventions are used to improve physical functioning in the elderly [31] and to counteract fatigue in somatic patients [32]. These positive effects can also be expected in depressed individuals engaging in regular exercise [33, 34]. Therefore, the second aim of this study is to examine the effect of exercise treatment on additional (mental) health outcomes, focusing on fitness, physical activity, health-related quality of life, disability, and motivation and energy.

Most research has focused on the effectiveness of exercise treatment for depression, with increasing but still limited attention for its mechanisms of change. Recently, Kandola and colleagues [35] reviewed evidence for the biological and psychosocial working mechanisms of physical activity and exercise specifically. They report evidence for increased neuroplasticity, especially in the hippocampus which is relevant to cognitive emotional processing and memory functions [35,36,37]. The psychosocial mechanisms are less well understood, with some research pointing toward self-esteem, social support, and self-efficacy [35, 38]. The authors therefore conclude that especially research on cognitive and psychosocial mechanisms is desirable. Knowing how an intervention works is essential to improving intervention techniques. Therefore, the third aim of the present study is to investigate cognitive and psychosocial mechanisms of change, focusing on rumination, self-esteem, and memory bias.

Rumination is a common symptom of depression and associated with its onset, maintenance, and recurrence [39]. Studies showed that exercise not only affects depressive symptoms in general, but also decreases rumination [40, 41]. Those studies indicate that rumination may mediate the effect of exercise on depressive symptoms. Moreover, exercise increases self-esteem and initial findings suggest that self-esteem mediates the relation between exercise and depression [35]. We aim to replicate the evidence for rumination and self-esteem as possible mechanisms of change. In addition, we examine memory bias as potential mediator which is related to rumination [42, 43] and self-esteem [44]. Negative bias in recall of self-related information has been recognized as important factor in the development and maintenance of depression (see cognitive model by Beck) [45,46,47,48,49]. As previous research identified that neuroplasticity in the hippocampal circuit increases through exercise which is linked to memory bias [50], changes in this circuit may allow depressed individuals to process emotional information differently, possibly decreasing the automatic preferential recall of negative information and in turn depressive symptoms. In summary, the aim of the present study is threefold: 1) we will investigate the long-term (cost-)effectiveness of adjunct exercise treatment and 2) its effect on additional positive outcomes as well as, 3) possible mechanism of change, focusing on rumination, self-esteem, and memory bias.

Methods

Study design

In this pragmatic superiority trial, patients are randomly assigned to either gcSC or the exercise intervention adjunct to gcSC. Measurements take place at baseline (T0), after session 3 (after 3 exercise sessions or 3 weeks of gcSC alone; T1), 6 (T2), 9 (T3) and 12 (T4), and 6 (T5), 9 (T6), 12 (T7), and 15 (T8) months post-baseline. Patients in the gcSC condition can receive the adjunct exercise intervention after completion of the follow-up assessments.

Aims and hypotheses

-

1

The primary aim of the study is to evaluate the (cost-)effectiveness of exercise as adjunct treatment for depression in a randomized controlled trial (RCT). We expect that gcSC with the adjunct exercise intervention is more effective and cost-effective than gcSC alone in reducing depressive symptoms in outpatients with MDD, treated in Dutch specialised mental health services.

-

2

The second aim is to assess the effect of adjunct exercise treatment on physical activity, fitness, health-related quality of life, disability and motivation and energy. We hypothesize that gcSC plus adjunct exercise outperforms gcSC alone on these outcomes.

-

3

The third aim is to examine putative cognitive mechanisms of change. We expect that a reduction in ruminative thinking style, as well as, an increase in self-esteem and a decline in negative memory bias mediate the between-group effects on depression symptom severity.

Participants

We will include 120 adult outpatients diagnosed with MDD, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [51]. Exclusion criteria are: Below the age of 16, lifetime manic episode, current psychosis, chronic depression (i.e. current depressive episode > 2 years), dysthymic disorder, high health risks of physical activity based on the screening tool Physical Activity Risk Questionnaire (PAR-Q) [52], insufficient comprehension of the Dutch language to fill out the questionnaires, and physical, cognitive, or intellectual impairments interfering with participation or informed consent.

Sample size calculation

A recent meta-analysis on the effectiveness of exercise interventions compared to non-exercise comparators in adult outpatients with MDD [10] reports an overall medium to large effect on depressive symptoms, with Hedges’s g = 0.79. This meta-analysis included 11 trials, investigating both exercise as adjunct treatment to gcSC and exercise as monotherapy for depression. In order to provide the most optimal effect size estimate, we conducted our own meta-analysis, including only the trials examining the augmenting effect of exercise, to synthesize the available evidence from the most comparable trials. We identified four studies (moderate/high level of evidence; GRADE) [53] with similar designs to the present RCT that evaluated aerobic exercise as adjunct to gcSC in unipolar depressed mental health care outpatients, with depressive symptom levels as outcome [54,55,56,57]. The meta-analysis yielded a Hedge’s g effect size of 0.98 (95%CI = 0.51 ~ 1.45), se = 0.26, t = 3.84, p = .032, with only moderate heterogeneity, I2 = 37%. One study by Rueter and colleagues [56] appeared an outlier (based on the Galbraith plot). When removing this study to account for variations across studies, heterogeneity disappeared with I2 = 0%, while the effect size was similar to the original meta-analysis, including 11 trials (g = 0.79; 95%CI 0.42 ~ 1.17; se = 0.190; p = .053). Based on the latter, we assumed a between-group effect size of g = 0.70 for the power analysis.

The power calculation was based on guidelines offered by Hemming et al. [58] and accounted for the hierarchical data structure with patients being clustered in psychomotor therapists with a mean cluster size of N = 10 (range 5 ~ 15) [59] and an intra-cluster correlation of 0.05 [60], which introduces a design effect of 1.48. In addition, we assumed a correlation between baseline depressive symptoms and the relevant follow-up of r = 0.30 for the planned baseline-adjusted multilevel mixed analysis. In order to be able to detect an effect size g ≥ 0.70 as statistically significant at α < 0.05 (two-sided) with a power of (1-β) = 0.80, power analyses revealed a required minimum N = 60 per arm (N = 120 in total).

Procedure

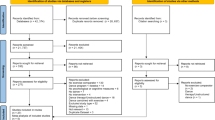

The current study takes place within the Dutch specialized mental health care setting and is a multicenter trial. Patients are recruited via Pro Persona mental health care (four locations: Arnhem, Ede, Nijmegen, Tiel), the Radboud University Medical Center (Nijmegen), and GGNet Network for mental health care (location Zutphen). If patients are eligible for participation, the therapists approach them for the study and they are contacted by a researcher. Study information is provided via a letter. Patients are contacted again after at least 48 h to discuss participation and answer any remaining questions. If patients decide to participate, they are asked to sign the informed consent form and are then randomized to either the gcSC condition or the gcSC with adjunct exercise treatment condition. The participant flow is depicted in Fig. 1.

Patients in the gcSC with adjunct exercise condition start the exercise treatment simultaneously to the gcSC treatment (with a maximum two-week difference between start dates). Patients complete the baseline assessment in the week before the first treatment session. The surveys are sent via email using the online cloud-based data solution program, Castor EDC and can be filled out via any personal device (e.g. computer, tablet). This program is also used for the Case Report Forms and initial data management. Additionally, patients receiving the adjunct exercise treatment fill out a short questionnaire before and after each supervised exercise session on paper, as part of the treatment. An overview of the assessments can be found in Table 1 and Fig. 1. Expected study duration is 36 months. Inclusion of patients started in March 2020.

Ethics

The present study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Arnhem-Nijmegen (under the registration code: NL72080.091.19) and is registered within the Netherlands Trial Register (code: NL8432). Because recently self-esteem was found to be a possible mechanism of change of exercise treatment [35], we decided to include a self-esteem measure after preregistration. All data will be processed in a confidential manner and data is processed using an identification code with only the principal investigator (PI) and the coordinating investigators (CI) having access to the key. The research process is regularly monitored by a trained and independent monitor, which includes monitoring of the completeness of informed consents, data safety, and correspondence with the ethics committee. Serious adverse events will be reported to the Medical Ethics Committee, although none are expected due to the low-risk intervention.

Randomization

Randomization is stratified for gender and setting, using Castor EDC. This program consecutively enrolls patients in line with a four, six and eight block design. These blocks are created for both strata separately. The first block is generated with the first randomization and thereafter a new block is randomly selected and generated when the previous one is used up. Allocation of patients is randomly selected from the block in use. More information on the randomization algorithm can be found on the website of Castor EDC.Footnote 1

Interventions

gcSC. The gcSC treatment is delivered in line with the Dutch multidisciplinary guidelines for depression treatment, consisting of pharmacological and/or psychological interventions which are offered individually or in group format.Footnote 2 The gcSC condition may also receive some form of body-oriented or physical activity treatment but no prescribed exercise treatment.

Adjunct exercise

Patients receiving the adjunct exercise treatment, exercise once a week under supervision of psychomotor therapists or trained nurses and commit to exercising twice a week at home for 12 weeks. Supervised exercise generally consists of running or indoor cycling (spinning), which are usually both offered in a group setting, although other exercise types and individual supervised exercise are also provided. The exercise sessions last for 45 min at moderate intensity, which is based on heart rate frequency (i.e. moderate = 64–76% of HRmax = 220 – age). This kind of exercise intervention is evidence-based and recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [61]. Patients track the intensity, duration, and frequency of each exercise session, with the aid of a non-invasive activity tracker (Fitbit)Footnote 3 which is provided for the length of the study (i.e. 15 months).

Material

Depressive symptoms

To assess the severity of depressive symptoms, as primary outcome of the RCT, the Dutch version of the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report (IDS-SR) [62] is used. This scale consists of 30 items, measuring the severity of different depressive symptoms on a four-point Likert scale. Validity and reliability have been established, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging between 0.76 and 0.82 in depressed outpatients [62].

Remission

The clinician-rated Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5-S) [63] is used to assess clinically defined remission at follow-up. The SCID-5-S is administered over the phone by trained and blinded assessors, conform recommendations [25]. The Dutch version was shown to have moderate to excellent inter-rater agreement of the Axis I disorders [64].

Physical activity and fitness

To assess self-rated physical activity level, the Dutch version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [65] is used. Psychometric properties of this questionnaire were shown to be acceptable in different settings and populations [66]. Moreover, to assess objective physical activity level and heart rate, patients receive the Fitbit in the adjunct exercise intervention condition, as it allows self-dosing during the exercise sessions, enables patients to learn how to effectively exercise to counteract depression, and helps patients motivate themselves, hence contributing to adherence. Additionally, to objectively assess physical fitness, fitness tests will be conducted at baseline and after the 12 weeks of exercise or gcSC treatment in 15% of the sample (selected at random). Here, the main endpoint is improvement in cardiorespiratory fitness.

Mood

Patients provide a positive and negative mood rating (on Visual Analogue Scales) directly before and after each supervised exercise session. They are encouraged to also use the mood ratings at home to monitor direct mood benefits. This is a technique used in clinical practice, to motivate patients to engage in exercise [67] and can thereby contribute to adherence and long-term exercise [68].

At-home exercise

Embedded in the same questionnaire as the mood ratings, patients indicate the type, frequency, duration, and intensity (mean and peak heart rate, as indicated by the Fitbit) of the previous two weekly at-home sessions. The psychomotor therapists/nurses discuss how the week went and together with the patient adapt the personalized exercise plan if needed. To motivate patients, different strategies are used that are integrated in the personalized plan. These strategies are based on previous research [67, 68] and psychomotor clinical practice and include psychoeducation, weekly exercise session scheduling, and goal setting.

Disability

Disability is assessed with the Dutch version of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) [69]. Thirty-six items are designed to measure functioning in different domains on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (i.e. no effort at all) to 4 (i.e. much effort). Reliability and validity of the scale are established for different populations [69].

Motivation and energy

To assess motivation and energy, the Motivation and Energy Inventory-Short Form (MEI-SF) [70] is used. The MEI-SF was translated into Dutch and then back-translated into English by bilinguals from the University of Texas at Austin. On 18 items, this scale measures the level of motivation and energy using seven-point Likert scales, ranging from 0 (i.e. none of the time) to 6 (i.e. all the time). This scale was specifically developed to evaluate interventions designed to improve motivation and energy in depressed patients. In previous research, Cronbach’s alpha ranged between .86 and .94 at baseline and .95 and .96 at the end of study, indicating high internal consistency [70].

Health-related quality of life

For the health-economic evaluation, changes in patients’ health-related quality of life are assessed with the EuroQol’s 5-level version, the EQ-5D-5L (https://euroqol.org) in combination with the Dutch tariff [71]. Patients indicate their health state on different domains (i.e. mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression), which is then transformed into a health state valuation (a utility score) which is anchored between 0 (i.e. dead) and 1 (i.e. perfect health). The utility is used to calculate the quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) over the studies follow-up time. Hence, the length of time spend in a particular health state is weighed by the utility score to obtain the QALY.

Healthcare costs

and costs stemming from productivity losses are assessed with the Trimbos Institute and iMTA Cost questionnaire for Psychiatry (Tic-P) [72] which measures resource use such as use of health services, patients’ and their family’s out-of-pocket costs, and lesser productivity owing to absenteeism and work cutback (presenteeism).

Rumination

Rumination is measured using the Dutch version of the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) which was shown to be a valid and reliable tool for this purpose [73]. This scale consists of 26 items which are rated on four-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (i.e. almost never) to 3 (i.e. almost always).

Self-esteem

Self-esteem is assessed using the Dutch version of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES) [74]. Global self-esteem is measured with ten items on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (i.e. strongly disagree) to 3 (i.e. strongly agree). Psychometric properties of the Dutch version were established, with a one-factor solution and high internal consistency [75].

Memory bias

To measure memory bias, the computerized Self-Referent Encoding Task (SRET) [76] is used. This task is a reliable method to assess memory bias [76, 77]. During the encoding phase, twelve positively and twelve negatively valenced adjectives are presented on the computer screen, one by one. No more than two words of the same valence are presented sequentially. Patients make a categorical decision whether the adjective is self-descriptive or not, by pressing on either of two keyboard buttons. After a 2 min distraction task (i.e., the Trail Making Test), the patients have 3 min to type in all the words they can remember from the previous task. Spelling errors are permitted.

Statistical analysis

Given the ongoing advances in statistics and technology, all analyses will be performed in line with best current practice. Following the CONSORT statement [78], all our analyses will adhere to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle (i.e., with an analysis of all patients as randomized). To this end, analyses of treatment effects will be conducted with multilevel mixed modelling, with treatment condition as factor and the depended measure as baseline covariate, while missing observations will be multiply imputed (with chained equations) for the health-economic analyses. In addition, we will also report the results in the per-protocol sample (≥ 6 supervised exercise sessions). Generalized (logit) mixed modelling will be used to compare the conditions on number of patients in remission at each follow-up measure. To examine whether rumination, self-esteem and memory bias are the mechanisms of change between adjunct exercise treatment and a decrease in depressive symptoms, multilevel structural equations modelling will be performed in Stata [79], or alternatively Hayes’ PROCESS macro [80] for SPSS [81] will be used.

Finally, a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) and cost-utility analysis (CUA) will be performed from a societal perspective [78]. We will consider four types of costs: 1) intervention costs, 2) healthcare costs, 3) patients’ and family out of pocket costs and opportunity costs of informal care, 4) productivity losses stemming from absenteeism and lesser efficiency while at work (presenteeism). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) will be computed to obtain the incremental costs per treatment responder and per QALY gained. Stochastic uncertainty will be handled using 2500 non-parametric bootstraps and by plotting the simulated ICERs on the ICER plane. For decision-making purposes, the ICER acceptability curve will be plotted for various willingness-to-pay (WTP) ceilings for making judgements whether the adjunctive exercise intervention offers good value for money relative to the care as usual comparator condition. One-way sensitivity analyses directed at uncertainty in the main cost drivers and outcomes will be performed to assess the robustness of our findings. Both the analysis and reporting of the findings will conform to the CONSORT [82], the Dutch guidelines for economic evaluations in health care, and CHEERS statements [78, 83]. All health-economic analysis will be conducted in R or Stata/SE 16.1 or later [79].

Discussion

The aim of the present study is to examine the (cost-)effectiveness of adjunct exercise treatment in the outpatient treatment of depression. We will also investigate long-term effects up to 15 months and the effect of exercise on additional outcomes such as physical activity and fitness, disability, health-related quality of life and motivation and energy. Finally, we aim to examine potential mechanisms of change, focusing on the major cognitive and psychosocial processes contributing to depression i.e. rumination, self-esteem, and memory bias.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. The RCT has the potential to provide a meaningful contribution to the literature on the cost-effectiveness and working mechanisms of an exercise prescription for the treatment of depression. The prospective study design enables us to follow patients for a period of 15 months post-baseline, to also examine the longer-term effects of exercise on depression. Finally, through the randomized design we will be able to compare whether adjunct exercise alongside usual care is more effective in decreasing depressive symptoms than gcSC alone. Because we provide the exercise intervention via psychomotor therapists and nurses who are already experienced in providing physical activity interventions, and do this within the naturalistic treatment setting, the RCT optimally facilitates later implementation of the evidence-based exercise protocol.

We further stimulate implementation in the (Dutch) mental health care system by flanking the RCT with a qualitative implementation study. The implementation study is two-folded. The first part will be used for scaling up and improving the implementation of an exercise augmentation prescription during the study. Psychomotor therapists/nurses, therapists who referred patients to the study, and patients who participated in the exercise treatment as well as patients who refused participation are interviewed to share their experiences. This allows for the identification of barriers and facilitating factors from an organisational level as well as an individual (patient) level. These results will be translated immediately to daily practice to enhance the implementation of prescribed exercise already during the RCT. The second part of the implementation study will identify facilitators and barriers for nationwide implementation once the current study shows (cost-)effective results. This will be based on (group-based) interviews with stakeholders who participated in the current research and for example with insurance companies and the clinical guidelines for depression treatment committee. The final results of the implementation study will be summarized in an implementation plan for future rollout.

Despite these strengths, there are some limitations that should be considered. First, patients in both conditions receive usual care in accordance with the Dutch multidisciplinary guidelines. While this reflects clinical practice, treatment heterogeneity in the gcSC is expected, as different psychological and/or pharmacological interventions are provided in different dosages and in varying formats (e.g. either group-based or individual CBT). Therefore, we can only draw general conclusions about the degree in which gcSC is augmented and merely explore which type of treatment is augmented most by exercise treatment. Nonetheless and due to the randomized design, the heterogeneity in gcSC should be similar across conditions, thus not thwart the study’s internal validity, while at the same time it increases the external validity of this pragmatic trial. Another benefit of a pragmatic trial is that future results can be optimally generalized and it facilitates the implementation of exercise in clinical practice, if proven (cost-)effective.

Other limitations are that exercise treatment is implemented as add-on treatment to gcSC which might lead to improvements in depressive symptoms due to nonspecific therapy effects such as more attention by therapists or peer support. The use of the Fitbit can also act as a co-intervention in the context of this trial, as it provides personal physiological feedback to patients in the exercise treatment condition. Finally, because patients decide whether they want to participate, there might be a selection bias due to the voluntary nature of the intervention. One may expect that patients who have a positive attitude toward exercise are more likely to participate. We register the reasons for refusal to participate and will explicitly invite patients who did not want to participate for our qualitative implementation study, in order to address the self-selection issue. Importantly, even if exercise treatment only attracts certain individuals, it can be an effective treatment module for depression, not limiting the additional value of this study in examining an accessible and acceptable treatment for depression.

Clinical implications

Even though exercise as treatment for depression is proven effective and recommended in the NICE guidelines [61], it is generally not implemented following evidence-based guidelines, in Dutch (and international) clinical practice, neither is it included in educational programs of mental health care providers. This study will not only facilitate the implementation of prescribed exercise treatment but also aims to contribute to the much-needed improvement of MDD treatment outcome in an acceptable, effective, and cost-effective way.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Notes

For more information on the randomization algorithm of Castor EDC, see https://helpdesk.castoredc.com/article/50-the-randomization-algorithm-in-castor.

For the Dutch multidisciplinary guidelines we refer to the https://www.ggzstandaarden.nl/zorgstandaarden/depressieve-stoornissen.

Patients can either choose to use the Fitbit Alta HR or the Fitbit Charge 3. For more information on Fitbit, we refer to the website of the provider https://www.fitbit.com/de/home.

Abbreviations

- MDD:

-

Major depressive disorder

- gcSC:

-

guideline concordant Standard Care

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behaviour therapy

- IPT:

-

Interpersonal therapy

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- APA:

-

American Psychological Association

- PAR-Q:

-

Physical Activity Risk Questionnaire

- PI:

-

Principal investigator

- CI:

-

Coordinating investigators

- IDS-SR:

-

Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report

- SCID-5-S:

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5

- IPAQ:

-

International Physical Activity Questionnaire

- WHODAS:

-

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule

- QALY:

-

Quality-adjusted life-years

- MEI-SF:

-

Motivation and Energy Inventory-Short Form

- Tic-P:

-

Trimbos Institute and iMTA Cost questionnaire for Psychiatry

- RRS:

-

Ruminative Response Scale

- RSES:

-

Rosenberg self-esteem scale

- SRET:

-

Self-Referent Encoding Task

- ITT:

-

Intention-to-treat

- CEA:

-

Cost-effectiveness analysis

- ICER:

-

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

References

GBD. Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7.

Correll CU, Solmi M, Veronese N, Bortolato B, Rosson S, Santonastaso P, et al. Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: a large scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):163–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20420.

Capuron L, Lasselin J, Castanon N. Role of adiposity-driven inflammation in depressive morbidity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(1):115–28. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2016.123.

World Health Organization. Depression [updated 2020, Jan 30; cited 2020, Aug 10]. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, Pike CT, Kessler RC. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(2):155–62. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.14m09298.

Cuijpers P, Van Straten A, Andersson G, Van Oppen P. Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. J Consult Psychol. 2008;76(6):909–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013075.

DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Young PR, Salomon RM, et al. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):409–16. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409.

Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, Schmaling KB, Kohlenberg RJ, Addis ME, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Psychol. 2006;74(4):658–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658.

Hardeveld F, Spijker J, De Graaf R, Nolen WA, Beekman ATF. Prevalence and predictors of recurrence of major depressive disorder in the adult population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;22(3):184–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01519.x.

Morres ID, Hatzigeorgiadis A, Stathi A, Comoutos N, Arpin-Cribbie C, Krommidas C, et al. Aerobic exercise for adult patients with major depressive disorder in mental health services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36(1):39–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22842.

Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, Lawlor DA, Rimer J, Waugh FR, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD004366. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6.

Mead GE, Morley W, Campbell P, Greig CA, McMurdo M, Lawlor DA. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD004366. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub3.

Rimer J, Dwan K, Lawlor DA, Greig CA, McMurdo M, Morley W, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD004366. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub5.

Abdollahi A, LeBouthillier DM, Najafi M, Asmundson GJ, Hosseinian S, Shahidi S, et al. Effect of exercise augmentation of cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment of suicidal ideation and depression. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:58–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.012.

Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Moore KA, Craighead WE, Herman S, Khatri P, et al. Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(19):2349–56. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.159.19.2349.

Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Doraiswamy PM, Watkins L, Hoffman BM, Barbour KA, et al. Exercise and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(7):587–96. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e318148c19a.

Gary RA, Dunbar SB, Higgins MK, Musselman DL, Smit AL. Combined exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy improves outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69(2):119–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.01.013.

Toups M, Carmody T, Greer T, Rethorst C, Grannemann B, Trivedi MH. Exercise is an effective treatment for positive valence symptoms in major depression. J Affect Disord. 2017;209:188–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.058.

Trivedi MH, Greer TL, Church TS, Carmody TJ, Grannemann BD, Galper DI, et al. Exercise as an augmentation treatment for nonremitted major depressive disorder: a randomized, parallel dose comparison. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(5):677–84. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.10m06743.

Sukhato K, Lotrakul M, Dellow A, Ittasakul P, Thakkinstian A, Anothaisintawee T. Efficacy of home-based non-pharmacological interventions for treating depression: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e014499. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014499.

Babyak M, Blumenthal J, Herman S, Khatr P, Doraiswamy M, Moore K, Baldewicz TT, Krishnan KR. Exercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 months. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:633–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200009000-00006.

Cornelissen VA, Smart NA. Exercise training for blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(1):e004473. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.112.004473.

Wright A, Cattan M. Physical activity and the management of depression. Working Older People. 2009;13(1):15–8. https://doi.org/10.1108/13663666200900004.

Krogh J, Nordentoft M, Sterne JA, Lawlor DA. The effect of exercise in clinically depressed adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(4):529–38 Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK82005/.

Krogh J, Hjorthøj C, Speyer H, Gluud C, Nordentoft M. Exercise for patients with major depression: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e014820. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014820.

Kerling A, Tegtbur U, Gützlaff E, Kück M, Borchert L, Ates Z, et al. Effects of adjunctive exercise on physiological and psychological parameters in depression: a randomized pilot trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;177:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.006.

Lavie CJ, Ozemek C, Carbone S, Katzmarzyk PT, Blair SN. Sedentary behavior, exercise, and cardiovascular health. Circ Res. 2019;124(5):799–815. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312669.

Moore SM, Charvat JM, Gordon NH, Roberts BL, Pashkow F, Ribisl P, et al. Effects of a CHANGE intervention to increase exercise maintenance following cardiac events. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(1):53–62. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3101_9.

Opdenacker J, Boen F, Coorevits N, Delecluse C. Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention and a structured exercise intervention in older adults. Prev Med. 2008;46(6):518–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.017.

Sevick MA, Dunn AL, Morrow MS, Marcus BH, Chen GJ, Blair SN. Cost-effectiveness of lifestyle and structured exercise interventions in sedentary adults: results of project ACTIVE. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00154-9.

Giné-Garriga M, Roqué-Fíguls M, Coll-Planas L, Sitja-Rabert M, Salvà A. Physical exercise interventions for improving performance-based measures of physical function in community-dwelling, frail older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(4):753–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2013.11.007.

Mustian KM, Alfano CM, Heckler C, Kleckner AS, Kleckner IR, Leach CR, et al. Comparison of pharmaceutical, psychological, and exercise treatments for cancer-related fatigue: a meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(7):961–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6914.

Huang TT, Liu CB, Tsai YH, Chin YF, Wong CH. Physical fitness exercise versus cognitive behavior therapy on reducing the depressive symptoms among community-dwelling elderly adults: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(10):1542–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.05.013.

Schuch FB, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Borowsky C, Zimmermann AB, Rocha NS, Fleck MP. Exercise and severe major depression: effect on symptom severity and quality of life at discharge in an inpatient cohort. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;61:25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.11.005.

Kandola A, Ashdown-Franks G, Hendrikse J, Sabiston CM, Stubbs B. Physical activity and depression: towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;107:525–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.09.040.

Campbell S, MacQueen G. The role of the hippocampus in the pathophysiology of major depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2004;29(6):417–26 http://jpn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/29-6-417.pdf.

Medina JL, Jacquart J, Smits JA. Optimizing the exercise prescription for depression: the search for biomarkers of response. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;4:43–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.02.003.

Jacquart J, Dutcher CD, Freeman SZ, Stein AT, Dinh M, Carl E, et al. The effects of exercise on transdiagnostic treatment targets: a meta-analytic review. Behav Res Ther. 2019;115:19–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.11.007.

Papageorgiou C, Wells A. Depressive rumination: nature, theory and treatment. New York: Wiley; 2004.

Bernstein EE, McNally RJ. Acute aerobic exercise hastens emotional recovery from a subsequent stressor. Health Psychol. 2017;36(6):560–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000482.

Brand S, Colledge F, Ludyga S, Emmenegger R, Kalak N, Sadeghi Bahmani D, et al. Acute bouts of exercising improved mood, rumination and social interaction in inpatients with mental disorders. Front Psychol. 2018;9:249. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00249.

Hertel P, Mor N, Ferrari C, Hunt O, Agrawal N. Looking on the dark side: rumination and cognitive-bias modification. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2(6):714–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702614529111.

Lyubomirsky S, Caldwell ND, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of ruminative and distracting responses to depressed mood on retrieval of autobiographical memories. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75(1):166–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.166.

Christensen TC, Wood JV, Barrett LF. Remembering everyday experience through the prism of self-esteem. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29(1):51–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202238371.

Beck AT. Depression: clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. New York: Harper & Row; 1967.

Beck AT, Bredemeier K. A unified model of depression: integrating clinical, cognitive, biological, and evolutionary perspectives. Clin Psychol Sci. 2016;4(4):596–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702616628523.

Gotlib IH, Joormann J. Cognition and depression: current status and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:285–312. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131305.

Johnson SL, Joormann J, Gotlib IH. Does processing of emotional stimuli predict symptomatic improvement and diagnostic recovery from major depression? Emotion. 2007;7(1):201–6. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.201.

LeMoult J, Kircanski K, Prasad G, Gotlib IH. Negative self-referential processing predicts the recurrence of major depressive episodes. Clin Psychol Sci. 2017;5(1):174–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702616654898.

Hamilton JP, Gotlib IH. Neural substrates of increased memory sensitivity for negative stimuli in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(12):1155–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.12.015.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: Author; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

Warburton DE, Jamnik VK, Bredin SS, McKenzie DC, Stone J, Shephard RJ, et al. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: an introduction. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36:S1–2. https://doi.org/10.1139/h11-060.

Kavanagh BP. The GRADE system for rating clinical guidelines. PLoS Med. 2009;6(9):e1000094. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000094.

Mota-Pereira J, Silverio J, Carvalho S, Ribeiro JC, Fonte D, Ramos J. Moderate exercise improves depression parameters in treatment-resistant patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(8):1005–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.02.005.

Pilu A, Sorba M, Hardoy MC, Floris AL, Mannu F, Seruis ML, et al. Efficacy of physical activity in the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorders: preliminary results. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2007;3(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-0179-3-8.

Rueter MA. The effect of running on individuals who are clinically depressed (MSc thesis master thesis). State College: Pennsylvania State University; 1980.

Veale D, Le Fevre K, Pantelis C, De Souza V, Mann A, Sargeant A. Aerobic exercise in the adjunctive treatment of depression: a randomized controlled trial. J R Soc Med. 1992;85(9):541–4 Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1433121.

Hemming K, Girling AJ, Sitch AJ, Marsh J, Lilford RJ. Sample size calculations for cluster randomised controlled trials with a fixed number of clusters. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-10.

Eldridge SM, Ashby D, Kerry S. Sample size for cluster randomized trials: effect of coefficient of variation of cluster size and analysis method. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(5):1292–300. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyl129.

Adams G, Gulliford MC, Ukoumunne OC, Eldrige S, Chinn S, Campbell MJ. Patterns of intra-cluster correlation from primary care research to inform study design and analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(8):785–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.12.013.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults: recognition and management. [updated 2009, Oct 28; cited 2020, Aug 10]. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90/chapter/1-Guidance#care-of-all-people-with-depression.

Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, Trivedi MH. The inventory of depressive symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol Med. 1996;26(3):477–86. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700035558.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders: patient edition. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute Pub; 1998.

Lobbestael J, Leurgans M, Arntz A. Inter-rater reliability of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID I) and Axis II disorders (SCID II). Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18(1):75–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.693.

Vandelanotte C, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Philippaerts R, Sjöström M, Sallis J. Reliability and validity of a computerized and Dutch version of the international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ). J Phys Act Health. 2005;2(1):63–75. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2.1.63.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–95. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB.

Otto M, Smits JA. Exercise for mood and anxiety: proven strategies for overcoming depression and enhancing well-being. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011.

Glowacki K, Arbour-Nicitopoulos K, Burrows M, Chesick L, Heinemann L, Irving S, et al. It's more than just a referral: development of an evidence-informed exercise and depression toolkit. Ment Health Phys Act. 2019;17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2019.100297.

Ustun, TB, Kostanjesek N, Chatterji S, Rehm J, World Health Organization. Measuring health and disability : manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0). 2010. Available from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43974.

Fehne SE, McLeod LD, Edin HM, Hogue SL. Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of the motivation and energy inventory – short form (MEI-SF). Poster presented at the ISOQOL 2004 Symposium; 2004. Available from https://www.rtihs.org/sites/default/files/mei-sf.pdf.

Versteegh MM, Vermeulen KM, Evers AA, De Wit GA, Prenger R, Stolk EA. Dutch tariff for the five-level version of the EQ-5D. Value Health. 2016;19(4):343–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2016.01.003.

Hakkaart-Van Roijen L, van Straten A, Donker M, et al. Trimbos/ iMTA questionnaire for costs associated with psychiatric illness (TIC-P): institute for medical technology assessment. Trimbos: Erasmus University Rotterdam; 2002.

Raes F, Hermans D, Eelen P. Kort instrumenteel De Nederlandstalige versie van de ruminative response scale (RRS-NL) en de rumination on sadness scale (RSS-NL) [the Dutch version of the ruminative response scale (RRS-NL) and the rumination on sadness scale (RSS-NL)]. Gedragstherapie. 2003;6(2):97–104 Available from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2003-99801-002.

Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1965.

Franck E, De Raedt R, Barbez C, Rosseel Y. Psychometric properties of the Dutch Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Psychol Belg. 2008;48(1):25–35. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb-48-1-25.

Derry PA, Kuiper NA. Schematic processing and self-reference in clinical depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1981;90(4):286–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.90.4.286.

Dobson KS, Shaw BF. Specificity and stability of self-referent encoding in clinical depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1987;96(1):34–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.96.1.34.

Zorginstituut Nederland. (2016). Richtlijn voor het uitvoeren van economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. [Guidelines for computing ecomonic evaluations in health care]. Available from https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/over-ons/werkwijzen-en-procedures/adviseren-over-en-verduidelijken-van-het-basispakket-aan-zorg/beoordeling-van-geneesmiddelen/richtlijnen-voor-economische-evaluatie.

StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 16. College Station: StataCorp LLC; 2019.

Hayes AF. PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. 2012. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk: IBM Corp; 2020.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Trials. 2010;1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-11-32.

Huserau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. BMC Med. 2013;29(2):117–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462313000160.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Marieke Koning for her insights and practical contribution to the exercise treatment protocol.

Funding

This project (with project number 852002022; main applicant is JV) is financed by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW). The funder reviewed the study protocol as part of the application process, but has no role in study design, data collection, analysis or publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD, BW, FS, IT, [JS]1, [JS]2, JV, and OP designed the current trial, with JV as principle investigator. Moreover, FS and JV calculated the required sample size for the RCT. TD designed the implementation study. The manuscript draft was written by MS. All authors gave valuable feedback on the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Arnhem-Nijmegen (under the registration code: NL72080.091.19). Patients are referred by their therapists and provide written informed consent. After at least 48 h of consideration and the possibility to ask questions, patients sign the informed consent to participate. Particpants have the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmitter, M., Spijker, J., Smit, F. et al. Exercise enhances: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial on aerobic exercise as depression treatment augmentation. BMC Psychiatry 20, 585 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02989-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02989-z