Abstract

Background

The aim of the current study is to assess the cross-sectional association of chronic non-communicable diseases (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, arthritis, and cerebrovascular) with depressive symptoms among older adults in China.

Methods

Data was obtained from the China Longitudinal Ageing Social Survey (CLASS) conducted in 2014. A total of 7505 participants were included. Depressive symptoms status was assessed by 9-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Associations between depressive symptoms and chronic diseases, adjusting for so, demographics and chronic diseases risk factors were assessed by using logistic regression model.

Results

We found negative associations between depressive symptoms and several socioeconomic factors, including education attainment and economic level. Widowed/divorced/ unmarried individuals are more likely to suffer from depressive symptoms. Hypertension (Odds ratio:1.29 [95%CI:1.16, 1.42]), diabetes (1.41 [95%CI:1.19,1.67]), arthritis (1.72 [1.52, 1.96]), and cerebrovascular disease (1.69 [1.41, 2.02]) were found to be associated with depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

Most depressive symptoms cases were found to be significantly associated with chronic diseases. Our findings have provided evidence for understanding co-morbid depressive symptoms with chronic diseases, which could help clinicians to evaluate, diagnose and manage depression promptly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Depression, which affects approximately 350 million people across the world, is an important public health issue [1, 2]. Depression had become the fourth leading cause of disease burden [1] and will become the second leading cause of disease burden in near future [3]. People with depression are usually associated with low quality of life, prevalence of cancer, chronic diseases, and higher mortality [4]. Depression causes a heavy burden on families, communities and health services in both high-income and low- and middle-income countries [5, 6].

In China, the prevalence of depression had aggressively increased to 17% among the elderly population [7, 8]. A number of studies suggested that there was an inverse or U-shaped association between prevalence of depression and age [9,10,11]. Moreover, several socioeconomic variables are related to depression [12], although these associations are inconsistent [8, 13]. Many studies found that low education level is associated with a high risk of depression in China [14, 15].

Several chronic diseases were found to be associated with depression [16,17,18]. With age increases, the presence of biological risk factors makes elder people vulnerable to depression [19, 20]. The positive correlation between depression and specified chronic diseases were found among the adult population in the developed countries [19, 20]. However, limited studies have found such a correlation in the developing countries [21,22,23], although the development of a chronic disease can bring on depression reaction. Because the chronic diseases and depression shared similar risk factors and pathophysiological process, the association between chronic diseases and depression have presented strong link [19, 20].

Currently, there is limited epidemiologic evidence linking chronic diseases status with depression risk among Chinese older population. Therefore, we investigated the association of chronic diseases status with depressive symptoms risk using data from the Chinese Longitudinal Ageing Social Survey (CLASS) in China.

Methods

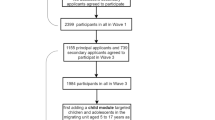

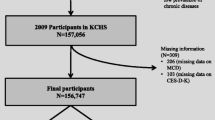

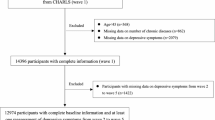

Setting and sample

In the current study, we used the data from the baseline of the Chinese Longitudinal Ageing Social Survey (CLASS) that was collected by the National Survey Research Center, Renmin University of China. This survey was stratified, multi-stage, probabilistic sampling survey, which coved 28 provincial areas in China. Details of the design and conduct of the study have been described elsewhere [24]. A total of 11,511elderly aged 60 or above was interviewed by face to face. In the present study, the sample is comprised of 7505 subjects aged 60 or above who had finished the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) and other independent variables of interest.

Depressive symptoms assessment

Depressive symptoms was assessed using an abbreviated nine-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), which is reliable and valid for detecting depressive symptoms among Chinese older adults [25]. In the CLASS study, the internal Cronbach’s alpha for CES-D used was 0.75. Using Kohout’s formula [26], standardized cut scores are determined by dividing the total possible score on a short CES-D scale by 60 (the total possible score on the full 20-item CES-D) and multiplying that number by 16 (the established cut score on the full 20-item CES-D. For current study, on a 9-item scale, the total possible score is 18 (9 items multiplied by 2, the highest response). That total score is divided by 60, which equals 0.3. Then, the 0.3 is multiplied by 16, resulting in a standardized cut score of 4.8 for the 9-item form of the CES-D.

Independent variable of interest

We included the following socioeconomic characteristics in our study: age (60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80+), gender (male, female), residence (rural, urban), marital status (married, widowed/divorced/unmarried), education level (junior high school and above, primary school, never attended school), ethnicity (Han, Others), and living arrangements (lives alone, lives with others). Income is categorized into five levels using the quintiles of household income (Yuan) (Q1: ≤ 3000, Q2: > 3000 and ≤ 10,000, Q3: > 10,000 and ≤ 24,000, Q4: > 24,000 and ≤ 36,000, Q5: > 36,000). We dichotomized the physical disability status, which was assessed by using ten-item version of the activities of daily living (ADL) scale, into two groups (“no functional problems”= 0, “has at least one limitation”=1) [27]. The participants were also asked whether they had one of the following health problems (covered 23 chronic disease), including hypertension (Yes, No), diabetes mellitus (Yes, No), arthritis (Yes, No), cerebrovascular disease (Yes, No), liver disease, and so on. Number of comorbid chronic disease were further categorized into “0”, “1” and “≥2”.

Statistical analysis

The difference between subjects with/without depressive symptoms was tested by χ2 test with proportions. The logistic regression model was used to calculate the adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of depressive symptoms (yes/no) with the covariates: age group, gender, residence, marital status, education, ethnicity, physical disability, living arrangement, and wealth quantiles. Separate multiple logistic regression models were used to assess the association of depressive symptoms with each chronic disease. In each model, the exposure of interest was one chronic disease and other covariates (mentioned above) were included. All two-way interactions between each chronic disease and covariates were assessed in multivariable adjusted models. The trend of the association was assessed with ordinal scores assigned to number of comorbid chronic disease. Statistical significance was declared with a two-sided p-value < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Selected characteristics of the subjects with/without depressive symptoms are summarized in Table 1. In the current study, male subjects, urban residents, people living with others, and the Han nationality accounted for a majority of the Chinese elderly population. As compared with the subjects without depressive symptoms, the depressive symptoms cases were slightly older and had a higher proportion of female subjects and physical disability, but a lower proportion of them are living with others.

The associations between subjects’ characteristics and depressive symptoms were presented in Table 2. There was a significantly weaker association between residence, education, and wealth quantile with depressive symptoms. People who were widowed/divorced/ unmarried, with physical disability or live alone were 1.34 times (p-values< 0.001), 2.82 times (p-values< 0.001), and 1.62 tines (p-values = 0.017) as likely to have depressive symptoms, respectively.

The odds ratio of chronic diseases for depressive symptoms was presented in the Table 3. After controlling for most important confounders, having hypertension [OR:1.29, 95%CI: (1.16–1.42)], diabetes mellitus [OR:1.41, 95%CI: (1.19–1.67)], arthritis [OR: 1.72, 95%CI: (1.52–1.96)], and cerebrovascular disease [OR: 1.69, 95%CI: (1.41–2.02)] were associated with depressive symptoms (all p-values< 0.001). The odds ratios of depressive symptoms presented positive associated with the number of chronic disease (Ptrend < 0.001).

Discussions

Very limited studies had explored the association between depressive symptoms and chronic diseases in China. More than 80% of subjects who were with depressive symptoms had chronic diseases. Our findings showed a strong positive association between depressive symptoms and chronic diseases under consideration of socioeconomic confounders.

We found significant associations between depressive symptoms and several socioeconomic factors, such as education attainment, economic level, physical disability and so on. In previous studies, positive associations between gender, age and depressive symptoms were reported [28]. However, we did not observed similar association in the current study. Similar positive association between depressive symptoms and being without spouse or having a lower education level or less wealth was also observed [28]. Low socioeconomic status could make people more likely with depressive symptoms through some mechanisms such as unsafe and unstable environments, malnutrition, reduced possibility of education, and limitedly access to health care services [28].

In the current study, we observed increased odds ratios of depressive symptoms in those with chronic disease, including diabetes mellitus and cerebrovascular disease. The associations between diabetes, hypertension with depressive symptoms were similarly compared with previous studies [19, 20]. These associations could be explained by several mechanisms, including unhealthy lifestyle, shared genetic influences, and inflammation in both diseases [29]. Previous studies also suggested some behavioral or biological pathways that link depressive symptoms with diabetes [30]. Furthermore, we found a positive association between depressive symptoms and arthritis after taking socioeconomic factors into consideration. The risk of depressive symptoms of participants with arthritis is 1.72 times as much as those without arthritis. Previous studies suggested that pain and physical disability experience could lead a side effect on their mood [20]. Another explanation is subjects having depressive symptoms might be more sedentary than those without depressive symptoms, which could cause an increased bone resorption and a lowered bone formation [31, 32].

Our study has several strengths, including the large sample size, the population-based design, and adjustment for a wide range of socioeconomic characteristics. Another noticeable strength is that the measure of all physical illnesses took place prior to the CES-D measurement, thus it helped to minimize the risk of reverse causation. However, our study also has several limitations, which should be taken into consideration by future researchers. As a cross-sectional study, we cannot deduce causative pathways between depressive symptoms and chronic diseases; therefore, future longitudinal research is needed to assess the causal relationships between depressive symptoms, chronic diseases and socioeconomic factors. Moreover, the CLASS does not provide sufficient information on lifestyle factors (i.e., weight, height, smoking, alcohol drinking, and so on) as risk factor of depressive symptoms, which should be cautioned in future studies.

Conclusions

In the current study, our findings suggest a particular need for recognition of depressive symptoms in the primary care. The increasing population with chronic non-communicable and mental health should be cautioned for public health policy makers and future studies. Our findings have provided evidence for understanding co-morbid depressive symptoms with chronic diseases, which could help clinicians to evaluate, diagnose and manage depression promptly.

Availability of data and materials

The data is available on request from Institute of Gerontology and National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China, who can be contacted through http://class.ruc.edu.cn/index.php?r=index/index&hl=en. Shen Geng had received permission and accessed to all the data.

Abbreviations

- CES-D:

-

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale

- CLASS:

-

the China Longitudinal Ageing Social Survey

References

Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Degenhardt L, Feigin V, Vos T. Global burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: an analysis from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116820.

Hyman S, Chisholm D, Kessler R, Patel V, Whiteford H. Mental disorders. Disease Control Priorities Related to Mental, Neurological, Developmental and Substance Abuse Disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442.

Cuijpers P, Vogelzangs N, Twisk J, Kleiboer A, Li J, Penninx BW. Comprehensive meta-analysis of excess mortality in depression in the general community versus patients with specific illnesses. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:453–62.

World Health Organization. Depression–a global public health concern; 2012. http://158.232.12.119/mental_health/management/depression/who_paper_depression_wfmh_2012.pdf. Accessed 8 Oct 2019.

Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:334–41.

Li D, Zhang DJ, Shao JJ, Qi XD, Tian L. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58:1–9.

Zhang L, Xu Y, Nie H, Zhang Y, Wu Y. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among the older in China: a meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:900–6.

Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, Shahly V, Bromet E, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, et al. Age differences in the prevalence and co-morbidity of DSM-IV major depressive episodes: results from the WHO world mental health survey initiative. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:351–64.

Pan A, Franco OH, Wang YF, Yu ZJ, Ye XW, Lin X. Prevalence and geographic disparity of depressive symptoms among middle-aged and elderly in China. J Affect Disord. 2008;105:167–75.

Yunming L, Changsheng C, Haibo T, Wenjun C, Shanhong F, Yan M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for depression in older people in Xi’an China: a community-based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:31–9.

Gao S, Jin Y, Unverzagt FW, Liang C, Hall KS, Ma F, et al. Correlates of depressive symptoms in rural elderly Chinese. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:1358–66.

Djernes JK. Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(7):372–87.

Lorant V, Croux C, Weich S, Deliège D, Mackenbach J, Ansseau M. Depression and socio-economic risk factors: 7-year longitudinal population study. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:293–8.

Zhou X, Bi B, Zheng L, Li Z, Yang H, Song H, et al. The prevalence and risk factors for depression symptoms in a rural Chinese sample population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99692.

Dalton SO, Laursen TM, Ross L, Mortensen PB, Johansen C. Risk for hospitalization with depression after a cancer diagnosis: a nationwide, population-based study of cancer patients in Denmark from 1973 to 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1440–5.

Hsu YT, Liao CC, Chang SN, Yang YW, Tsai CH, Chen TL, et al. Increased risk of depression in patients with Parkinson disease: a Nationwide cohort study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:934–40.

Ayerbe L, Ayis S, Wolfe CD, Rudd AG. Natural history, predictors and outcomes of depression after stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:14–21.

Clarke DM, Currie KC. Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: a review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Med J Aust. 2009;190:54–60.

Dickens C, McGowan L, Clark-Carter D, Creed F. Depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:52–60.

Arokiasamy P, Kowal P, Capistrant BD, Gildner TE, Thiele E, Biritwum RB, Yawson AE, et al. Chronic noncommunicable diseases in 6 low-and middle-income countries: findings from wave 1 of the world health organization's study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE). Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:414–28.

Lin H, Guo Y, Kowal P, Airhihenbuwa CO, Di Q, Zheng Y, et al. Exposure to air pollution and tobacco smoking and their combined effects on depression in six low-and middle-income countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;211:157–62.

Mendenhall E, Norris SA, Shidhaye R, Prabhakaran D. Depression and type 2 diabetes in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Diabetes res. Clin. Pract. 2014;103:276–85.

Guo Q, Bai X, Feng N. Social participation and depressive symptoms among Chinese older adults: a study on rural-urban differences. J Affect Disord. 2018;239:124–30.

Merril S, Zhen C, Shuzhuo L. Intergenerational transfers and living arrangements of older people in rural China: consequences for psychological wellbeing. J Gerontol. 2006;61:S256–66.

Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5(2):179–93.

Feng Q, Zhen Z, Gu D, Wu B, Duncan PW, Purser JL. Trends in ADL and IADL disability in community-dwelling older adults in Shanghai, China, 1998–2008. J Gerontol. 2013;68:476–85.

Mojtabai R, Olfson M. Major depression in community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults: prevalence and 2-and 4-year follow-up symptoms. Psychol Med. 2004;34:623–34.

Fiske A, Wetherell JL, Gatz M. Depression in older adults. Ann. Rev. Clin Psychol. 2009;5:363–89.

Knol M, Twisk JW, Beekman AT, Heine R, Snoek FJ, Pouwer F. Depression as a risk factor for the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus. A meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2006;49:837.

Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol Ser A. 2003;58:M249–65.

Menuki K, Mori T, Sakai A, Sakuma M, Okimoto N, Shimizu Y, Kunugita N, et al. Climbing exercise enhances osteoblast differentiation and inhibits adipogenic differentiation with high expression of PTH/PTHrP receptor in bone marrow cells. Bone. 2008;43:613–20.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Institute of Gerontology and National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China for providing the CLASS data.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry and UKRI's Global Challenge Research Fund (ES/P011055/1). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit this article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZW and HY conceived and designed the study. SG received permission and accessed to all the data for this project. ZW and HY performed the statistical analysis. ZW wrote the first draft of the paper. HY, ZG and BL contributed to the acquisition of data. ZW, HY, ZG, BL, and SG contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The survey was also conducted within the article 38, 39, and 40 of the Constitution of People’s Republic of China and the legal framework governed by Chapter I, Article 9 from the statistics law of the People’s Republic of China. Therefore, the study was not reviewed by ethics committee. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The design of this survey was within the article 38, 39, and 40 of the Constitution of People’s Republic of China and the legal framework governed by Chapter I, Article 9 from the statistics law of the People’s Republic of China. Verbal informed consent was acceptable and was not reviewed by ethics committee. Moreover, the interviewer also had documented the more details information on the process of obtaining informed consent, which included whether agree to attend this study, the time of agree to attend this study, the reasons of disagree to attend this study, and so on. Details of informed consent was stored by the Institute of Gerontology and National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No conflict of interest exits in the submission of this manuscript, and manuscript is approved by all authors for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Yang, H., Guo, Z. et al. Socio-demographic characteristics and co-occurrence of depressive symptoms with chronic diseases among older adults in China: the China longitudinal ageing social survey. BMC Psychiatry 19, 310 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2305-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2305-2