Abstract

Background

Most of patients with dementia are cared for by family members. Caring for people with dementia is challenging; approximately 30–55% of caregivers suffered from anxiety or depressive symptoms. A range of studies have shown that psychosocial interventions are effective and can improve caregivers’ quality of life, reduce their care burden, and ease their anxiety or depressive symptoms. However, information on the acceptability of these interventions, despite being crucial, is under-reported.

Methods

Systematic searches of databases were conducted for literature published on EMBASE, PubMed, The Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and PsycARTICLES until August 2017 and the searches were updated on June 2018. The selection criteria included primary studies with data about the acceptability of psychosocial interventions for informal caregivers and publications written in English. Two authors independently selected studies, extracted study characteristics and data, assessed the methodological quality of the included studies by using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Research Checklist, and conducted a narrative synthesis of quantitative and qualitative data.

Results

A total of 10,610 abstracts were identified through systematic searches. Based on screening titles and abstracts, 207 papers were identified that met the criteria for full paper review, with 42 papers from 13 different countries meeting the inclusion criteria. We found high- and moderate-quality evidence showing psychosocial interventions were acceptable, with important benefits for caregivers. Facilitators of acceptability included caregivers’ need for intervention, appropriate content and organization of the intervention, and knowledge and professionalism of the staff. Barriers to acceptability included participants’ poor health status and low education levels, caregiving burden, change of intervention implementers, and poor system performance of interventions.

Conclusion

There is preliminary evidence to support the acceptability of psychosocial interventions for dementia caregivers. However, the available supporting evidence is limited, and there is currently no adequate information from these studies indicating that the acceptability has received enough attention from researchers. More well-designed studies assessing psychosocial interventions are needed to give specific statements about acceptability, and the measure of acceptability with psychosocial interventions should be more comprehensive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Caring for people with dementia is challenging, as most patients may lose the ability to understand and communicate effectively, and general care hardly improves their condition [1]. Compared with caregivers in other conditions, dementia caregivers provide more assistance, give up their vacations or hobbies more often [2,3,4], and have a higher risk of becoming physically and mentally ill [4, 5]. Marcia et al.’s studies have shown that 55% of dementia caregivers had to give up pleasurable personal activities [4], and about 30–55% of caregivers suffered from anxiety or depressive symptoms [6,7,8], which may have resulted in changes in their behavior and reduced quality of care.

Derived from wide-ranging theories and concepts, psychosocial interventions mean physical, cognitive or social activities that aim at addressing a specific health or social care problem [9, 10]. There are a range of studies showing that psychosocial interventions are moderately effective for dementia caregivers, which can improve caregivers’ quality of life, reduce their care burden, and ease their anxiety or depressive symptoms [9, 11,12,13,14,15]. However, those psychosocial interventions often encounter many difficulties. For example, although understanding the needs and situations of caregivers is valuable and crucial for developing effective intervention plans, few programs systematically assess caregiver needs [16]. Coupled with a number of other constraints, such as transportation barrier, time constraints, and stigma [17], many caregivers refused to participate in the intervention. Moreover, many trials neither had a practice manual nor specific description about the process of interventions, making them difficult to be reliably replicated in practice [18]. Additionally, training for intervention implementers is often difficult to complete or not widely available under the constraints of many factors [18]. Moreover, due to differences in culture, economic development and social resources, few psychosocial interventions can be widely accepted and implemented among caregivers in different regions [19].

As a construct in public health practice, acceptability means the reaction of intended recipients and refers to judgments by participants and others on whether intervention procedures are appropriate, fair, and reasonable for the problem or participants [20, 21]. When translating the results from trials to practice, a key component in the uptake and success of an intervention is its acceptability to targeted individuals, which may have direct implications for its dissemination and utilization [22, 23]. Many studies in this field do not measure acceptability directly but report the following indicators as acceptability of psychosocial interventions: take-up rates, drop-out rates, and caregivers’ evaluation of the intervention (e.g., satisfaction, preference) [22, 24,25,26]. To develop effective interventions for caregivers of people with dementia, it is important to understand whether the intervention is acceptable in practice and what elements and which methods are acceptable. The current review aims to systematically assess evidence for the acceptability of psychosocial interventions for informal caregivers of people with dementia and to summarize the factors related to the acceptability of psychosocial interventions. The findings in this review may inform the development and implementation of future research and enhance the application value of psychosocial interventions for dementia caregivers.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched the Web of Science, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, PubMed, and PsycARTICLES with no restrictions on date or language of publication up until 18 August 2017 and conducted an update search on 02 June 2018. Search terms were gathered into four facets: dementia (including dementia, Alzheimer Disease, Vascular Dementia, Huntington Disease, etc.), informal caregiver (including carer*, caregiver*, family relations, etc.), psychosocial intervention (including psychosocial/psychological/non-pharmacological intervention*, family intervention, psycho-education*, cognitive, psychotherapy, social/emotional/information support, exercise, etc.), and acceptability (including acceptability, adherence, compliance, satisfaction, utilization, etc.). See Additional file 1 for a full search strategy.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

We included studies that fulfilled all the following criteria:

● Participants: family, informal, unpaid caregivers of patients with dementia or dyads (dementia patients and their informal caregivers).

● Intervention: any psychosocial interventions delivered to informal caregivers of people with dementia, aimed at improving their function or quality of life or providing support.

● Outcome: participation rate, completion rate, or caregivers’ evaluation of the intervention (satisfaction, preference, etc.).

● Study design: quantitative or qualitative studies.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies if:

● The study was not in English.

● The study included both informal and formal caregivers.

● The report was a review, meta-analysis, conference abstract, pilot study, letters, or protocol.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was independently assessed by two reviewers (DQ and MH) using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment for quantitative studies [27,28,29], which enables an assessment of selection bias, study design, use of blinding, the level of confounding, data collection methods and data analysis. For qualitative studies, we used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist [30], which includes 10 aspects, such as appropriateness of the methodology, research design, recruitment strategy, data collection, ethical issues, and influence of the relationship between researcher and participants. See Additional file 2 for details on the quality assessment.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted on country of origin, year of publication, study design, sample size, workforce, setting, and measures of acceptability independently by two reviewers (DQ and MH). The qualitative and quantitative data of included studies were combined in a synthesis [31,32,33]. The results were grouped, where possible, by two analytical themes: (i) the acceptability of psychosocial interventions, included take-up rates, drop-out rates, and caregivers’ evaluation of the intervention, (ii) factors related to the acceptability of psychosocial interventions, included facilitators of acceptability and barriers to acceptability. In the initial analysis, only high-quality and medium-quality articles were included; when the evidence was not sufficient, the low-quality articles were analyzed. Consensus was reached on discrepancies in data extraction through discussion.

Results

Study selection

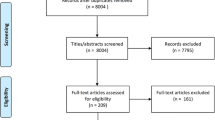

A total of 10,610 references were identified. After excluding duplicates, 7211 articles were screened. By screening titles and abstracts, 207 papers were identified that met the criteria for full paper review. Among them, 43 were excluded for not about dementia or informal caregivers, 13 were excluded for not reporting data on acceptability, 24 were excluded for not psychosocial interventions, 8 were excluded for not in English, 28 were excluded for repeated data, 23 were excluded for no full text available and 26 were excluded because they are not original studies (reviews, conference abstract, protocol, etc. Finally, a total of 42 eligible articles were included in this systematic review (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of studies

The included studies were from 13 countries in North America, Europe, Asia and Oceania. The studies presented a wide variety of designs, including 29 randomized controlled trials, 8 pre-test /post-test or quasi-experimental designs, 3 qualitative studies and 2 mixed-method designs. Ten of the included studies were on cognitive activities, 2 on physical activities, 6 on social activities and 24 on other psychosocial interventions (such as case management, combined physical and cognitive activities, combined social and psychological activities, et al.). Details about interventions in the studies are presented in Additional file 3. Workforce and settings of interventions are described in Table 1.

Quality assessment

We completed 44 quality assessments on the 42 included studies; two studies [34, 35] with mixed-methods design each had 2 quality assessments done. Details of the methodological quality assessments of all 42 studies are in Additional file 2. From the 42 papers, 21 (50%) studies were rated as strong [17, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55], 15 (36%) were rated as moderate [24,25,26, 35, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66], and 6 (14%) were rated as low [34, 67,68,69,70,71]. Most of the included studies used data collection tools with high reliability and validity, and differences in the quality assessment arose mainly from sample representativeness, drop-out rates, integrity of intervention, and appropriateness of the analysis.

Results of data synthesis

Three themes for acceptability of the interventions emerged: recruitment and participation rate, completion rate, and participants’ satisfaction with the intervention [22, 72]. Two themes on factors related to the acceptability of interventions emerged: facilitators of acceptability and barriers to acceptability. Of the 40 included studies that had data about the acceptability of the interventions, 13 studies showed either quantitative or qualitative data about factors related to the acceptability of interventions. Details about the acceptability of the interventions in the studies are described in Table 2.

Acceptability of the interventions

Recruitment and participation rate

A total of 20 high- and moderate-quality papers presented the actual participation rate after recruitment. Twelve studies were rated as high (the actual participation rate was ≥ 80%), including 2 social [36, 54], 3 cognitive [48, 50, 61], one physical [45], and 6 other psychosocial interventions [25, 35, 43, 46, 55, 60]. Three multi-component psychosocial intervention studies were rated as moderate (60–79% participation) [17, 49, 52]. Five studies were rated as low (less than 60% participation), including one social [57], one physical [59], and 3 other psychosocial interventions [47, 64, 66].

One low quality study showed low participation rate (31.8%) after the recruitment [67].

Completion rate

Thirty-one high- and moderate-quality studies reported data on participants’ completion rate with the interventions, ranging from high to low levels. Sixteen papers showed high completion rate (80% participants completed the intervention), including 5 social [36, 37, 54, 57, 63], one cognitive [40], one physical [45] and 9 other psychosocial interventions [17, 44, 46, 49, 51, 53, 55, 56, 66]. Fourteen showed moderate completion rate (60–79% participants completed), including 4 cognitive [48, 50, 61, 62], one social [65], one physical [59] and 8 other psychosocial interventions [24, 25, 35, 47, 52, 58, 60, 64]. Only one cognitive intervention study showed low completion rate [38] (less than 60% participants completed the intervention).

Five low-quality papers reported data on participants’ completion rate for the interventions. Three studies showed moderate completion rate [34, 69, 70], while the other 2 reported low completion rate [67, 68].

Participants’ satisfaction with the interventions

Thirteen high- and moderate-quality studies reported either quantitative or qualitative data on participant satisfaction with the interventions. These data indicated overall good levels of satisfaction. Caregivers in two studies (one cognitive and one multi-component intervention) showed average satisfaction scores above 3 (5 = highest satisfaction) [38, 60], and another two American papers (one cognitive and one multi-component intervention) [25, 39] showed average satisfaction scores above 5 (7 = highest satisfaction). The caregivers said that they would be very likely to recommend the program to others [25]. In two Finland studies, including one self-management intervention and one nutritional intervention, most (more than 90%) of the dyads estimated that the intervention was useful, and 80% of dyads felt that they benefited from participation [41, 44]. Similarly, most of the participants (more than 90%) in three cognitive intervention studies and one social intervention study were satisfied with the program [43, 48, 57, 61]. A Spanish paper reported that 97.7% of caregivers and 88.6% of therapists considered the cognitive intervention to be useful, and 6 months later, 93.2% of caregivers and 86.3% of therapists still considered it to be useful [40]. Caregivers (73%) in another study who received a multi-component psychosocial intervention also indicated that they benefitted a great deal from participating in the project [42].

Three low-quality papers showed data about participant satisfaction. More than 80% of the dyads in 2 cognitive intervention studies (in Australia and America) said the training was perceived to be very useful [69, 71]. Caregivers (71%) in another study on multi-component intervention reported that there was nothing about the intervention that was unacceptable to them [34].

Factors related to the acceptability of the interventions

Cognitive intervention

Caregivers in an individual cognitive stimulation therapy program [62] reported that it was difficult to fit in the intervention because of time constraints, such as having a full-time/part-time paid job. Pot [38] summarized that the primary reason for refusal of participation was a claimed lack of need. Liddle et al. [69] reported the influence of participants’ health status as barriers to intervention acceptability.

Social intervention

Caregivers highlighted the importance of appropriate content of the intervention. Mahoney’s [36] study reported that one of the most frequently used modules (the weekly caregiver conversation) was informative, making them feel more knowledgeable about dementia. Xiao et al. found that limited English proficiency and low literacy level in caregivers were identified as barriers to the program [37]. Another barrier was change of the intervention implementer, which was a main reason for caregivers who did not comply with the intervention [37].

Physical intervention

One study on physical intervention [59] noted anecdotally that caregiver burden was a barrier for acceptability, with many participants dropping out because of increased caregiver burden. Apart from that, some caregivers dropped from the study because of medical complications.

Other psychosocial interventions

Three studies [25, 41, 60] highlighted two key facilitators of acceptability: the professionalism of the intervention team and their friendly attitude. Two studies noted the importance of applicability of the intervention. Prick et al. [24] found that possibility to exercise during the intervention was the most named reason by the dyads to participate in the program. Approximately 68.5% of the dyads in the intervention group continued to exercise at home. Caregivers in a Resourcefulness Training program [26] said the intervention was too time-consuming, and they did not like the method for practicing the skills. Four studies reported participants’ health status as barriers to intervention acceptability. Prick et al. [24] found that physical complaints from the dyads were barriers for delivery of the exercise component. Similarly, some participants withdrew due to ill health in another 3 studies [25, 41, 64]. Woods and Joling et al. summarized that the primary reason for refusal of participation was a claimed lack of need for this intervention [64, 67].

Discussion

Key findings

This systematic review examined the acceptability of psychosocial interventions for dementia caregivers. Forty-two papers were included and showed some high- and moderate-quality evidence supporting the acceptability of psychosocial interventions, with important benefits yielded for caregivers. Currently, however, there is not adequate evidence from these studies indicating that the acceptability of psychosocial interventions for dementia caregivers has received enough attention from researchers. Most studies only included data about completion rate, and less than half of the papers reported on take-up rates and participants’ evaluation of interventions.

Cognitive intervention

Ten studies (3 for dyads and 7 for caregivers only) on cognitive intervention were included, 3 reported high participation rate [48, 50, 61], 8 studies showed low to high completion rate [38, 40, 48, 50, 61, 62, 69, 70], 8 studies indicated good levels of satisfaction [38,39,40, 48, 61, 69, 71]. Three reported on barriers to acceptability, including time constraints [62], lack of need [38], participants’ poor health [69]. Completion rate in dyadic studies was more stable than caregiver-only studies, except that, no other discernable difference between dyadic studies or caregiver-only studies was noted. The included studies showed overall good levels of acceptability, while in another research, Milders et al. [73] indicated that the acceptability of cognitive intervention may be overlooked, responses from the participants gave an over optimistic impression of the acceptability. Therefore, acceptability of cognitive interventions is still to be explored in future studies.

Social intervention

Six studies on social intervention were included. Three reported on participation rate [36, 54, 57], 6 studies showed moderate to high completion rate [36, 37, 54, 57, 63, 65], only one study reported caregivers’ satisfaction with the social intervention [57], and 2 reported on factors related to acceptability. Appropriate content of the intervention was a facilitator [36], while the change of implementers was a barrier [37], the evidence showed the importance of intervention content and stable implementation team. Apart from that, language and literacy problems in caregivers were identified as barriers to acceptability [37]. Similarly, Cook et al., in other studies, said that the diversity of languages and cultures acts as an obstacle to developing, testing and implementing evidence-based psychosocial interventions [19].

Physical intervention

Two physical intervention studies were included, reporting both participation rate and completion rate [45, 59]. Caregiver burden and poor health status was reported as barriers to acceptability of exercise program [59]. Similarly, Lamotte et al. [74] indicated that caregiver burden and physical limitation were potential challenges of implementing exercise interventions, which could influence recruitment of participants and outcomes (such as caregiver burden or adherence to the exercise regimen). Considering the limited information included, acceptability of physical interventions is still to be explored in future studies.

Other psychosocial intervention

Twenty-four studies included both social and psychological intervention as well as exercise elements, making it difficult to make a clear distinguishing between them. In addition, it was usually hard to clearly differentiate components between social interventions and psychological interventions [10], so we grouped these multi-component interventions studies together. Thirteen [17, 25, 35, 43, 46, 47, 49, 52, 55, 60, 64, 66, 67] of the 24 included studies reported on low to high participation rate, 20 [17, 24, 25, 34, 35, 44, 46, 47, 49, 51,52,53, 55, 56, 58, 60, 64, 66,67,68] showed low to high completion rate, 8 [17, 25, 34, 41,42,43, 56, 60] indicated participants’ satisfaction and 10 reported limited but important information about factors related to the acceptability of interventions. No discernable difference between dyadic studies or caregiver-only studies was noted.

One essentially important but usually ignored concept in most caregiving research is the implementation of intervention, which is highly related to acceptability of intervention. Acceptability often assumes the intervention was implemented as planned, which is not often the case [75]. Implementation fidelity is an important indicator for treatment outcome evaluation, as it truly reflects whether failure to replicate the expected outcomes is a problem with the intervention itself or of its application [76]. Besides, much of caregiving literature does not report data on treatment components, which make it difficult to evaluate exactly how the combination of different components contributed to the intervention’s success in multi-component interventions [11]. In the current review, only six included studies [25, 43, 46, 49, 56, 61] reported data on implementation measurement. Therefore, reporting data on implementation fidelity and treatment components are quiet important.

Additionally, when involved in an intervention program, caregivers were often required to make changes in their own caregiving behavior. Behavioral change is a process that unfolds over time, involving progression through six stages [77]. The stage of change model incorporate action as but one stage, preceded by precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation, and followed by maintenance and termination [78]. A series of studies reported that readiness to change was related to participants’ adherence to treatment [79, 80]. However, as a construct related to acceptability, participants’ readiness to change behavior have always been overlooked. In this review, only one included study [46] has assessed readiness to change among caregivers. They found that the stage of change was a predictive factor for adherence to the intervention. Examining readiness to change may yield valuable information about how to improve acceptability, and how to help participants fully benefit from interventions.

Limitations

Several limitations of this review need to be considered. First, we reviewed both qualitative and quantitative studies, included a broad range of interventions, and used multiple outcomes and diverse measures of acceptability. The heterogeneity between these studies makes it impossible to meta-analyze the data or make comparisons between studies. Second, in an attempt to obtain the most comprehensive literature possible, we included some low-quality studies, and considering the limited number of high quality studies (only 50%). This may have resulted in potential bias in some areas. Finally, the implementation of psychosocial interventions is a complicated process that is dependent on the environment and where it occurred [81]. All the included studies came from developed countries, and 88% were delivered by specialists. Although we conducted a systematic search, the lack of data on developing countries and non-specialist delivered psychosocial interventions represents an important gap in the evidence. Additionally, data about participants’ evaluation of the interventions were mainly on satisfaction, and information on satisfaction was only provided for intervention completers. Limited information was available for caregivers who had discontinued with the intervention.

Implications for future research and practice

The number of high-quality trials evaluating the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for caregivers of people with dementia continues to increase [17, 82]. Those interventions, however, may be clinically effective but unacceptable to participants [83]. To fully understand and improve the acceptability of psychosocial interventions in practice, future studies need to evaluate the needs and readiness to change of caregivers, improve the applicability of interventions before implementation. Moreover, measures of acceptability of the interventions should be more comprehensive and should include drop-out rates, take-up rates and participants’ evaluations. To successfully translate effective interventions from research settings into real world practice, it is also important to make a practice manual that reports more details about implementation of the intervention, such as fidelity of implementation, attendance at sessions and how staff training for intervention implementers was undertaken.

As an indicator for acceptability, Satisfaction presumes the consumer can compare the current product (intervention) with other options. But caregivers do not necessarily know what else may be available. Therefore, satisfaction is an important indicator, because it indicates the experience was relatively positive, but the value is limited. Future studies should be more rigorous on evaluation of acceptability.

In addition, based on the result from this review, there is a lack of acceptability data on dementia caregivers in low- and middle-income countries. Future studies should also focus on the practicality and acceptability of psychosocial interventions in low- and middle-income countries, which are important and crucial to ease caregivers’ care burden and improve their quality of life [84].

Conclusion

There is preliminary evidence to support the acceptability of psychosocial interventions for dementia caregivers. However, the available supporting evidence is limited, and there is currently no adequate information from these studies indicating that the acceptability has received enough attention from researchers. More well-designed studies assessing psychosocial interventions are needed to give specific statements about acceptability, and the measure of acceptability with psychosocial interventions should be more comprehensive.

Abbreviations

- RCT:

-

randomized control trial

References

Association, A.s. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. 2017. USA: Alzheimer’s Association; 2017. p. 325–73.

International, A.s.D. World Alzheimer Report 2015. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2015.

Schulz R, Martire LM. Family caregiving of persons with dementia: prevalence, health effects, and support strategies. Am J Geriatr psychiatry. 2004;12(3):240–9.

Ory MG, H.I. RR, Yee JL. Prevalence and Impact of Caregiving: A Detailed Comparison Between Dementia and Nondementia Caregivers. The Cerontologist. 1999;39:177–85.

Van Mierlo LD, Meiland FJ, Van der Roest HG. Personalised caregiver support: effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in subgroups of caregivers of people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:1–14.

Ballard CG. A follow up study of depression in the carers of dementia sufferers. Br Med J. 1996;312:947.

Karlijn JJ, H.W J. The Two-Year Incidence of Depression and Anxiety Disorders in Spousal Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: Who is at the Greatest Risk? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(3):293–303.

MS ABS. Prevalence of mental health disorders among caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(12):1034–41.

Pusey H. A systematic review of the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for carers of people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2001;5:107–19.

McDermott O, et al. Psychosocial interventions for people with dementia: a synthesis of systematic reviews. Aging Ment Health. 2018;1:1–11.

Claire Dickinson JD, Gibson G. Psychosocial intervention for carers of people with dementia: what components are most effective and when? A systematic review of systematic reviews. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;29:31–43.

Selwood A, Johnston K, Katona C. Systematic review of the effect of psychological interventions on family caregivers of people with dementia. J Affect Disord. 2007;101:75–89.

Marim CM, Silva V, Taminato M, Barbosa DA. Effectiveness of educational programs on reducing the burden of caregivers of elderly individuals with dementia: a systematic review. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2013;21:267–75.

Brodaty H, Green A. A Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:657–64.

Boots LM, de Vugt ME, van Knippenberg RJ. A systematic review of Internet-based supportive interventions for caregivers of patients with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:331–44.

Sara J, Czaja LNG. Development of the risk appraisal measure: a brief screen to identify risk areas and guide interventions for dementia caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(6):1064–72.

Tremont G, et al. Psychosocial telephone intervention for dementia caregivers: a randomized, controlled trial. Alzheimers Dement : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2015;11:541–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2014.05.1752.

Orrell M. The new generation of psychosocial interventions for dementia care. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:342–3.

Moniz-Cook E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Woods B, Orrell M. Psychosocial interventions in dementia care research: the INTERDEM Manifesto. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15:283–90.

Bowen DJ. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):452–7.

Kazdin A. Acceptability of child treatment techniques: the influence of treatment efficacy and adverse side effects20. Behav Ther. 1981;12(4):493–506.

Kaltenthaler E, Sutcliffe P. The acceptability to patients of computerized cognitive behaviour therapy for depression: A systematic review. Psychol Med. 2008;38(11):1521.

Kay-Lambkin F, Baker A, Lewin T. Acceptability of a clinician-assisted computerized psychological intervention for comorbid mental health and substance use problems: treatment adherence data from a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(1):11.

Prick AE, et al. Process evaluation of a multicomponent dyadic intervention study with exercise and support for people with dementia and their family caregivers. Trials. 2015.

Whitlatch CJ, et al. Dyadic intervention for family caregivers and care receivers in early-stage dementia. Gerontologist. 2006;46(5):688–94.

Zauszniewski JA, et al. Resourcefulness training for women dementia caregivers: acceptability and feasibility of two methods. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2016;37(4):249–56.

EPHP, P. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. 2010.

EPHP, P. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies dictionary. 2009.

Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A Process for Systematically Reviewing the Literature: Providing the Research Evidence for Public Health Nursing Interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–84.

CASP. Ten questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Research Checklist 2013.

Mary Dixon-Woods SA, Jones D, Young B. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(1):45.

Lisa Arai NB, Popay J, Roberts H. Testing methodological developments in the conduct of narrative synthesis: a demonstration review of research on the implementation of smoke alarm interventions. Evid Policy A J Res Debate Prac. 2007;3(3):361–83.

Suri H, D C. Advancements in research synthesis methods: from a methodologically inclusive perspective. Rev Educ Res. 2009;79(1):395–430.

Roberts JS, Silverio E. Evaluation of an education and support program for early-stage alzheimer’s disease. J Appl Gerontol. 2009;28(4):419–35.

Barbabella F, et al. Usage and usability of a web-based program for family caregivers of older people in three European countries: a mixed-methods evaluation. Comput Inform Nurs. 2018;36(5):232–41.

Mahoney DM, Tarlow B, Jones RN. Factors affecting the use of a telephone-based intervention for caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. J Telemed Telecare. 2001;7:139–48.

Xiao LD, et al. The effect of a personalized dementia care intervention for caregivers from Australian minority groups. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016;31:57–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317515578256.

Pot AM, Blom MM, Willemse BM. Acceptability of a guided self-help internet intervention for family caregivers: mastery over dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(8):1343–54.

Beauchamp N, et al. Worksite-based internet multimedia program for family caregivers of persons with dementia. Gerontologist. 2005;45:793–801.

Martín-Carrasco M, Martín MF, Millán PR. Effectiveness of a psychoeducational intervention program in the reduction of caregiver burden in alzheimer’s disease patients’ caregivers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:489–99.

Puranen TM, Pitkala KH, Suominen MH. Tailored nutritional guidance for home-dwelling AD families: the feasibility of and elements promoting positive changes in diet (NuAD-trial). J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19(4):454–9.

Czaja SJ, et al. A videophone psychosocial intervention for dementia caregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(11):1071–81.

Zarit SH, et al. Fidelity and acceptability of an adaptive intervention for caregivers: an exploratory study. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17(2):197–206.

Laakkonen ML, Kautiainen H, Hölttä E, Savikko N. Self-management groups for people with dementia and their spousal caregivers. A randomized, controlled trial. Baseline findings and feasibility. Eur Geriatr Med. 2013;4:389–93.

Pitkälä KH, Pöysti MM, Laakkonen ML. Exercise rehabilitation on home-dwelling patients with Alzheimer disease: A randomized, controlled trial Baseline findings and feasibility. Eur Geriatr Med. 2011;2:338–43.

Chee YK, et al. Predictors of adherence to a skill-building intervention in dementia caregivers. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(6):673–8.

Livingston G, et al. Long-term clinical and cost-effectiveness of psychological intervention for family carers of people with dementia: a single-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(7):539–48.

Wilz G, Soellner R. Evaluation of a short-term telephone-based cognitive behavioral intervention for dementia family caregivers. Clin Gerontol. 2016;39(1):25–47.

Burgio L, et al. Impact of two psychosocial interventions on white and African American family caregivers of individuals with dementia. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):568–79.

de Rotrou J, et al. Do patients diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease benefit from a psycho-educational programme for family caregivers? A randomised controlled study. Int J Geriatr Psychiat. 2011;26(8):833–42.

Sogaard R, et al. Cost analysis of early psychosocial intervention in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;37(3–4):141–53.

Belle SH, et al. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):727–38.

Kwok T, Lam L, Chung J. Case management to improve quality of life of older people with early dementia and to reduce caregiver burden. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18(Suppl 6):4–6.

Eloniemi-Sulkava U, et al. Family care as collaboration: effectiveness of a multicomponent support program for elderly couples with dementia. Randomized controlled intervention study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:2200–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02564.x.

Mittelman MS, et al. Preserving health of Alzheimer caregivers: impact of a spouse caregiver intervention. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(9):780–9.

Jansen AP, et al. Effectiveness of case management among older adults with early symptoms of dementia and their primary informal caregivers: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48:933–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.004.

Hébert R, Leclerc G, Bravo G, Girouard D. Efficacy of a support group programme for care-givers of demented patients in the community: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gerontol Geriatr Suppl. 1994;18:1–4.

Coon DW, et al. Anger and depression management: psychoeducational skill training interventions for women caregivers of a relative with dementia. Gerontologist. 2003;43:678–89.

Castro CM, et al. An exercise program for women who are caring for relatives with dementia. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(3):458–68.

Orsulic-Jeras S, et al. The SHARE program for dementia: Implementation of an early-stage dyadic care-planning intervention. Dementia (London), 2016.

McCurry SM, et al. Adopting evidence-based caregiver training programs in the real world: outcomes and lessons learned from the STAR-C Oregon translation study. J Appl Gerontol. 2017;36(5):519–36.

Leung P, et al. The experiences of people with dementia and their carers participating in individual cognitive stimulation therapy. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(12):e34–42.

Winter L, Gitlin LN. Evaluation of a telephone-based support group intervention for female caregivers of community-dwelling individuals with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2006;21(6):391–7.

Woods RT, Orrell M, Bruce E, et al. REMCARE: Pragmatic Multi-Centre Randomised Trial of Reminiscence Groups for People with Dementia and their Family Carers: Effectiveness and Economic Analysis. PloS one. 2016;11(4):e0152843.

Mohide EA, et al. A randomized trial of family caregiver support in the home management of dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(4):446–54.

Vickrey BG, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):713–26.

Joling KJ, et al. The cost-effectiveness of a family meetings intervention to prevent depression and anxiety in family caregivers of patients with dementia: a randomized trial. Trials. 2013;14:305. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-14-305.

Dahlrup B, et al. Health economic analysis on a psychosocial intervention for family caregivers of persons with dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;37(3–4):181–95.

Liddle J, et al. Memory and communication support strategies in dementia: effect of a training program for informal caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(12):1927–42.

Callan JA, et al. Feasibility of a pocket-PC based cognitive control intervention in dementia spousal caregivers. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(6):575–82.

Joseph E, Gaugler JE, Hobday JV, Robbins JC. Effects of Online, Psychoeducational Training on Knowledge of Person-Centered Care and Satisfaction. J Gerontol Nurs. 2015;41(10):18–24.

Robinson L, et al. Effectiveness and acceptability of non-pharmacological interventions to reduce wandering in dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(1):9–22.

Milders M, et al. Cognitive stimulation by caregivers for people with dementia. Geriatr Nurs. 2013;34(4):267–73.

Lamotte G, et al. Exercise training for persons with Alzheimer’s disease and caregivers: a review of dyadic exercise interventions. J Mot Behav. 2017;49(4):365–77.

Rowe C, et al. Implementation fidelity of multidimensional family therapy in an international trial. J Subst Abus Treat. 2013;44(4):391–9.

Schoenwald SK, et al. Toward the effective and efficient measurement of implementation Fidelity. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2011;38(1):32–43.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48.

Prochaska JO, et al. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychol. 1994;13(1):39–46.

Alexander PC, et al. Stages of change and the group treatment of batterers: a randomized clinical trial. Violence Vict. 2010;25(5):571–87.

Mochari-Greenberger H, Terry MB, Mosca L. Does stage of change modify the effectiveness of an educational intervention to improve diet among family members of hospitalized cardiovascular disease patients? J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(7):1027–35.

Bird VJ, Le Boutillier C, Leamy M, Williams J, Bradstreet S, Slade M. Evaluating the feasibility of complex interventions in mental health services: standardised measure and reporting guidelines. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;5:5.

Blom MM, Zarit SH, et al. Effectiveness of an internet intervention for family caregivers of people with dementia: results of a randomized controlled trial. PloS one. 2015;10(2):e0116622.

Watson M. A framework for development and evaluation of RCTs for complex interventions to improve health. Int J Pharm Pract. 2000;14(4):233–4.

Kinosian BP, Stallard E, Lee JH. Predicting 10-Year Care Requirements for Older People with Suspected Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:631–8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study has been funded by China Medical Board for Shuiyuan Xiao, Central South University, China, as part of the program for improving development of Mental Health Policy in China (CMB14–188). The funding agency did not take part in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials related to the study can be obtained through contacting the first author at 166911058@csu.edu.cn.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DQ contributed to development of search protocol, developed the search strategy, conducted the database searches, extracted the data, conducted the analysis and compiled the first through final drafts. SYX advised on the inclusion/ exclusion criteria, advised on excluded articles, and reviewed first through final drafts. MH contributed to development of the protocol, developed the search strategy, advised on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, extracted the data, and reviewed first through final drafts. YY conducted the analysis and reviewed first through final drafts. BWT contributed to development of the protocol, developed the search strategy, and reviewed first through final drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Search strategy. (DOCX 36 kb)

Additional file 2:

Quality assessment. (DOCX 29 kb)

Additional file 3:

Description and quality ratings of included studies. (DOCX 54 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, D., Hu, M., Yu, Y. et al. Acceptability of psychosocial interventions for dementia caregivers: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 19, 23 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1976-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1976-4