Abstract

Background

Approximately 10% of the individuals experiencing the death of a loved one develop prolonged grief disorder (PGD) after bereavement. Family members of haematological cancer patients might be particularly burdened since their loss experience is preceded by a very strenuous time of disease and aggressive treatment. However, support needs of relatives of cancer patients often remain unmet, also after the death of the patient. Therapeutic possibilities are enhanced by providing easily available and accessible Internet-based therapies. This study will adapt and evaluate an Internet-based grief therapy for bereaved individuals after the loss of a significant other due to haematological cancer.

Methods

The efficacy of the Internet-based grief therapy is evaluated in a randomized controlled trial with a wait-list control group. Inclusion criteria are bereavement due to hematological cancer and meeting the diagnostic criteria for PGD. Exclusion criteria are severe depression, suicidality, dissociative tendency, psychosis, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorder, and current psychotherapeutic or psychopharmacological treatment. The main outcome is PGD severity. Secondary outcomes are depression, anxiety, somatization, posttraumatic stress, quality of life, sleep quality, and posttraumatic growth. Data is collected pre- and posttreatment. Follow-up assessments will be conducted 3, 6, and 12 months after completion of the intervention. The Internet-based grief therapy is assumed to have at least moderate effects regarding PGD and other bereavement-related mental health outcomes. Predictors and moderators of the treatment outcome and PGD will be determined.

Discussion

Individuals bereaved due to haematological cancer are at high risk for psychological distress. Tailored treatment for this particularly burdened target group is missing. Our study results will contribute to a closing of this healthcare gap.

Trial registration

German Clinical Trial Register UTN: U1111–1186-6255. Registered 1 December 2016.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Grieving is an emotional reaction to the loss of a loved one and refers to the transition between the loss experience and the adaptation to it [1] whereby intense feelings of mourning and yearning are considered normal and typically decrease over time [2]. According to Stroebe and Schut [3] the process of coping with bereavement is characterized by an oscillation between loss-oriented and restoration-oriented stressors. During this process the bereaved person alternates between confrontation with and avoidance of the different tasks of grieving which results in adjustment to bereavement.

However, some individuals develop a persistent grief reaction which is described as persistent complex bereavement disorder by the DSM-5 in the chapter of diagnoses that require further research [4]. In the ICD-11 this syndrome of persistent grief will probably be included as Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) [5]. DSM-5 and ICD-11 criteria for grief disorders describe the same diagnostic entity, differing merely semantically [6]. PGD is characterized by intense symptoms of grief enduring for more than 6 months post-loss, separation distress, intrusive thoughts, and feelings of emptiness or meaninglessness [7]. A recent meta-analysis revealed a prevalence of about 10% for PGD among bereaved adults [8]. The loss of a loved one can not only trigger PGD but also depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [9]. Persons suffering from chronic grief experience elevated levels of depression and mortality [10].

A loss due to cancer was shown to be a risk factor for PGD [11, 12] and depression [12] and to be as distressing as an unexpected natural loss (e.g., due to cardiac arrest, accident) [12]. Cancer ranks among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide [13]. In 2013 haematological cancer was the third most common cancer-related cause of death in Germany with 18,831 people who died due to this disease [14].

Cancer is a significant psychological burden for patients and for their loved ones. During the time of illness significant others of cancer patients show high distress with prevalence rates of 20 to 46% for depression and anxiety [15, 16], and lower health-related quality of life than the general population, especially if cancer is advancing [17]. Levels of distress, depression, and anxiety of family members were shown to be similar or even higher compared to cancer patients [15, 18,19,20]. Declined functional status and increased physical symptoms as well as higher psychological distress in cancer patients are associated with higher caregiver distress [18, 21, 22]. Especially haematological cancer patients are burdened by long and aggressive cancer treatments [23, 24] and show high distress [19, 20, 25, 26], as do their family members [19, 20, 26, 27]. These findings suggest a particularly high risk for adverse psychological outcomes in family members of haematological cancer patients. Yet, relatives of haematological cancer patients report more unmet supportive care needs than patients [20].

In the case of bereavement caregivers of cancer patients show a deterioration in mental health [28,29,30]. Impaired mental health during the time of the cancer experience predicted worse mental health after bereavement [31] and PGD [32]. Caserta and colleagues argue that a burdensome time of illness may deplete resources and impede bereavement adjustment [12].

Tough relatives of haematological cancer patients may be assumed to be at heightened risk for adverse outcomes after bereavement, there is a lack of studies focusing on bereavement adjustment among relatives of patients with haematological cancer. To our knowledge, only one study examined psychological well-being after bereavement due to haematological cancer and found lower psychological well-being in bereaved parents of children who underwent haematopoietic stem cell transplantation compared to other cancer-bereaved parents [33].

These results underline the need for support for bereaved relatives of cancer patients. Easily available and accessible support can be provided by Internet-based programs [34, 35]. Compared to face-to-face therapy Internet-based interventions facilitate more flexibility and anonymity as well as faster attainability [36, 37]. Internet-based interventions and face-to-face therapy show comparable positive effects, e.g., for depression [38]. Participants in Internet-based treatments reported a positive working alliance [39,40,41,42]. Despite the advantages of Internet-based programs Northouse et al. [43] found no study with an Internet-based intervention in their review of psychosocial interventions for caregivers of cancer patients. Therefore, our Internet-based grief therapy constitutes an important innovation, closing a research and supply gap.

In our study we use an Internet-based cognitive-behavioural grief therapy originally developed as “Interapy” by Lange and colleagues for the treatment of posttraumatic stress [35]. For the treatment of PGD cognitive-behavioural therapy proved efficacious, particularly exposure therapy [44, 45]. Interapy was adapted for PGD [46] and its efficacy was shown for various groups of bereaved individuals showing medium to large treatment effects [46, 47].

The main goal of our study is the adaptation and evaluation of the Internet-based cognitive-behavioural grief therapy for bereaved persons after the loss of a significant other due to haematological cancer, targeting primarily the reduction of PGD severity. The results of our study will provide information about the efficacy of Internet-based therapy for people who experienced a loss which is usually expected but preceded by a very burdensome time of disease and aggressive treatment.

Methods

The guided text-based intervention for people who suffer from PGD after bereavement due to haematological cancer is currently evaluated in a randomized waitlist-controlled trial. Questionnaires are administered at screening for eligibility (T-1), at baseline (T0), during the intervention (monitoring), at post-treatment (T1) and at three follow-up points (T2–4; 3, 6, and 12 months after intervention completion). Severity of PGD symptoms as measured with the Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG) [48] is the main outcome. All questionnaires and the intervention are administered via a secure website and data is stored on secure storage devices. The procedure is described in detail below.

Procedure

Recruitment practices

Short information about the study and a link to the study website is sent to a multitude of stakeholders, including support groups, charities, insurance companies, clinics and medical practices, owners or contact persons of relevant websites, online communities, and blogs in Germany. Flyers are sent via mail by request and distributed in departments of the University Medical Centre Leipzig, e.g., Psychosomatic Medicine, Medical Psychology and Medical Sociology, and Haematology and Medical Oncology.

The study website provides thorough information about the study and the Internet-based grief therapy. Interested persons can apply by submitting a screening questionnaire which determines whether they fulfil eligibility criteria. Contact information of the research team is provided to be addressed in case of questions and remarks.

Participant timeline

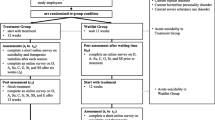

The procedure from screening to follow-up assessments is depicted in Fig. 1.

T-1, screening: Participants apply for the study via an openly accessible online questionnaire. Participants who may fulfil the eligibility criteria as described below will be contacted for a telephone screening, which includes the Prolonged Grief Interview [7, 49] and in case of eligibility concerns queries regarding participant’s answers in the online questionnaire. Participants who do not fulfil the eligibility criteria but show signs of suicidal ideation will also be called to ensure their safety and provide support in finding immediate help if necessary. Participants who are excluded from the study after the screening process will receive information about the reasons via e-mail and be offered help in finding an alternative treatment.

Informed consent: Participants meeting the eligibility criteria will be sent thorough information on the study and asked to send back a consent form, which also includes contact information of the participant’s general practitioner, who will be contacted in case of endangerment to self or others. Participants are informed about this requirement. Questions can be addressed to the research team at any time.

T0, baseline: After written informed consent, participants receive a personal link to the baseline questionnaire. Upon submission of this questionnaire participants are randomized as described below.

Treatment: The intervention group (IG) receives the intervention as described below. Those assigned to the waitlist-control group (WCG) will wait for five weeks before completing the first post-treatment assessment (T1.0). Subsequently, the same intervention as described above will be provided and an identical post-treatment assessment will be administered (T1.1) after the intervention. Participants in the WCG will be informed about this procedure immediately after randomization. For the sake of clarity the following nomenclature will be used subsequently: “treatment” describes the study phase between baseline and post-measurement and includes IG and WCG; “intervention” describes the Internet-based therapy that is conducted during treatment for IG and after the first post-treatment assessment for WCG.

T1, post-treatment: After completion of treatment, participants receive a link to the post-treatment questionnaire. The WCG receives an identical questionnaire again after completing the intervention.

T2–4, follow-up: 3, 6, and 12 months after cessation of the intervention, links to online follow-up questionnaires are sent to participants of both groups. All follow-up questionnaires are identical.

Randomization

Randomization takes place after the baseline assessment. Participants are randomized into one of two groups: IG or WCG. A permutated block randomization with a block size of four and equal probabilities to be sampled into either group is carried out with pseudo-seeds, using MersenneTwister. The used software was “Randomization in Treatment Arms” (RITA). Neither participants, nor the research team were blind to group allocation. Yet, this is not expected to lead to biased results, since all assessments after randomization are carried out anonymously and automated via online questionnaires.

Participants

Sample size and power calculation

Previous studies found effects of the Internet-based grief therapy of at least moderate size [46, 47]. Assuming moderate effect sizes, an alpha level of 0.05, and statistical power of 80% a target sample of 128 participants (64 for each group) is intended.

Eligibility criteria

Participants are eligible for the study if they are 18 years or older, speak German, have Internet access and meet the diagnostic criteria for PGD after bereavement due to haematological cancer. Exclusion criteria are current psychotherapy or unstable psychopharmacological treatment with changes within the last 6 weeks, severe depression, suicide ideation, dissociative tendency, psychosis, PTSD due to an event other than the loss, substance use disorder, and cognitive or physical impairments which make treatment participation impossible.

Intervention

Participants will receive therapist-assisted Internet-based grief therapy which applies the paradigm of structured writing. All therapeutic content, such as general information and writing instructions, is presented through a secure website (“Beranet”). Communication with the therapist is also conducted via an e-mail function of this website.

The Internet-based cognitive-behavioural grief therapy aims at working through the grief as well as coping with the new situation [46]. It is derived from a rationale developed by Lange et al. for individuals suffering from posttraumatic stress [35] which was adapted for PGD by Wagner et al. [46, 50, 51]. It is structured as a sequence of ten writing tasks in three phases: (1) self-confrontation, (2) cognitive restructuring, and (3) social sharing. The first phase focuses on loss-oriented coping, whereas phases two and three refer to restoration and integration of the loss experience [46].

Participants are instructed to plan out two writing tasks per week in advance, each lasting 45 min. They receive access to each writing task upon having completed the previous task. Once a week participants receive thorough feedback for their writing tasks from their therapist. All therapists are psychologists who were trained in the application of the intervention manual and receive supervision. Instructions for the writing tasks are mainly standardized and therapist instructions for individualized feedback are highly structured. Other than sending new writing tasks and feedback, therapists engage in further communication when directly contacted by the participant or when participants express critical experiences such as high distress or suicidal thoughts. In this case therapists address existing issues via mail or, if necessary, telephone. In case of endangerment of self or others, the participant’s general practitioner will be contacted to initiate immediate care for the participant.

Prior to the first phase, participants receive general information on the treatment, psychoeducation on the phases, and instructions on how to use the treatment platform. An overview of the Internet-based grief therapy and monitoring can be found in Table 1.

Phase 1: Self-confrontation. In four writing tasks participants describe their loss experience with a special emphasis on emotional and cognitive processes. They are instructed to write in as much detail as possible focusing on emotional and sensory perceptions, use present tense and first person, and not mind possible issues of style, grammar or orthography. The goal of this phase is to weaken feelings such as fear and guilt through reprocessing and therefore reduce avoidant behaviour.

Phase 2: Cognitive reappraisal. The next four writing tasks focus on a change of perspective to help participants develop realistic and helpful coping strategies. This is achieved by instructing participants to compose a supportive letter to a (possibly hypothetical) friend who endured the same kind of loss. The letter should reflect on and acknowledge burdensome feelings like guilt, fear, or anger, but also provide correction of unrealistic assumptions and dysfunctional thoughts. Participants are instructed to encourage their friend in activating resources, such as positive activities or social contacts as well as in finding rituals to express their mourning. The goal of this phase is to help participants define a new role for themselves and regain a sense of control over their lives.

Phase 3: Social Sharing. In the last two writing tasks participants are instructed to write a letter to a person concerned with the loss who can be also themselves or the deceased. The last letter serves as an opportunity to summarize and communicate what they may have learned during the therapeutic process and what they want to implement to cope with their loss experience.

New writing tasks are only released if the previous task has been completed. Participants can access past instructions, their texts and therapist feedback throughout the intervention and are encouraged to download all material for later rereading. Support for technical issues and issues regarding the intervention itself is provided via e-mail or telephone if necessary.

Before and after each writing task, participants complete a monitoring (Table 1) consisting of Self-Assessment-Manikin (SAM [52]), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 [53]), and Working Alliance Inventory (WAI-S [54]).

Measurements

The ICG [48] is used in its German version [55] to measure the primary outcome severity of PGD symptoms. It measures severity of PGD by assessing symptoms related to grief like yearning, intrusive thoughts, or resentment regarding the loss in 19 items which are rated by participants on a five-point Likert scale (never-always, 0–4) with regard to the last month. Three additional items were administered that are not included in the sum score but shall serve future comparability in the case of inclusion of PGD in ICD-11 as suggested by Maercker et al. [5]. They address feelings of guilt, difficulty accessing positive memories and anhedonia in questions adapted from Xiu et al. [56] as follows “I feel guilty about mistakes I made with regard to his/her death”, “It is really difficult for me to remember in detail happy moments with or images of him/her from the times before he/she died,” and “I no longer feel able to experience happiness, contentment, or joy since the loss of this person.”

Secondary outcomes, screening variables, moderators and mediators as well as used measures are summarized in Table 2.

Published German translations of measurement tools are used where available. For all other measurement tools [57,58,59,60], own translations were achieved as follows: the first authors translated the measurement tools from English to German. A native English speaker retranslated the result, which was then checked for accordance with the original tool. Any inconsistencies and challenges in translating, e.g., idioms, were discussed thoroughly within the research team.

In addition to the variables listed in Table 2, sociodemographic variables, current medical problems, drug and alcohol consumption, history of previous losses, traumatic experiences, and of psychological problems, and help-seeking behaviour are assessed at baseline (T0).

All measures except the Prolonged Grief Interview [49, 61] are assessed by online self-assessment questionnaires which minimizes potential assessment bias.

Statistical analysis

Demographic data and main outcomes will be reported using descriptive statistics. Chi-square and t-tests will be performed to examine whether randomization resulted in comparable groups and whether selective dropout occurred with regard to any pre-treatment characteristics.

To test the treatment effect, i.e. a significantly greater decrease in PGD and other mental health outcomes from baseline to post-treatment in the IG than in the WCG, a 2 × 2 repeated measure analyses of variance (ANOVA) will be conducted with time as the within-subject factor (baseline vs. post-treatment) and group as the between subject-factor (IG vs. WCG). Stability of treatment effects at 3, 6, and 12 month follow-up will be tested using two-tailed t-tests. Cohen’s d will be calculated to present effect sizes. Results will be shown for each outcome measure. Intention-to-treat analyses and completer analyses will be provided. Predictors of improvement in outcome measures and of dropout will be determined with linear and logistic regression analyses. To identify potential risk and protective factors for PGD severity and other bereavement outcomes as our secondary aim we will perform hierarchical regression analyses with baseline data, e.g., with religiousness, coping strategies, and attachment style as independent variables. All analyses will be conducted using SPSS, with an alpha level of 0.05.

Discussion

Family members of haematological cancer patients are highly burdened since they face high cancer-related distress which continues beyond bereavement. Their support needs often remain unmet. Easily available and accessible support is provided by Internet-based treatment programmes which were shown to have similar positive effects as face-to-face therapy, e.g., for depression [38]. To our knowledge there are no guided Internet-based therapies for bereaved individuals after the loss of a loved one due to haematological cancer. Our study aims at adapting and evaluating an Internet-based cognitive-behavioural grief therapy for this target group. Results of the study will provide information about the applicability and short- and long-term efficacy of the treatment regarding bereavement due to haematological cancer.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance

- ASA-27:

-

Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire

- BSS, BSIS:

-

Scale for Suicide Ideation

- BSSS:

-

Berlin Social Support Sales

- CTQ:

-

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

- DAAPGQ:

-

Depressive and Anxious Avoidance in Prolonged Grief Questionnaire

- DEQ:

-

Depressive Experience Questionnaire

- DSM-V:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener

- GEQ:

-

Grief Experience Questionnaire

- ICD-11:

-

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems

- ICG:

-

Inventory of Complicated Grief

- IES-R:

-

Impact of Event Scale-Revised

- IG:

-

intervention group

- IKT:

-

Prolonged Grief-13 – Interview version

- PGD:

-

prolonged grief disorder

- PGI:

-

Posttraumatic Growth Inventory

- PHQ:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- PTSD:

-

posttraumatic stress disorder

- QRI:

-

Quality of Relationships Inventory

- RQ:

-

Relationships Questionnaire

- SAM:

-

Self-Assessment-Manikin

- SBI-15R:

-

Systems of Belief Inventory

- SDPD:

-

Dutch Screening Device for Psychotic Disorder

- SDQ-5:

-

Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire

- SF-12:

-

Short-Form Health Survey

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- SWE:

-

Self-Efficacy Scale

- WAI:

-

Working Alliance Inventory

- WCG:

-

waitlist-control group

References

Parkes CM. Bereavement as a psychosocial transition: processes of adaptation to change. J Soc Issues. 1988:53–65.

Jordan AH, Litz BT. Prolonged grief disorder: diagnostic, assessment, and treatment considerations. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2014;45:180–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036836.

Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud. 1999;23:197–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201046.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Maercker A, Brewin CR, Bryant RA, Cloitre M, Ommeren M, Jones LM, et al. Diagnosis and classification of disorders specifically associated with stress: proposals for ICD-11. World Psychiatry. 2013;12:198–206.

Maciejewski PK, Maercker A, Boelen PA, Prigerson HG. “Prolonged grief disorder” and “persistent complex bereavement disorder”, but not “complicated grief”, are one and the same diagnostic entity: an analysis of data from the Yale Bereavement Study. World Psychiatry. 2016:266–75.

Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, Parkes CM, Aslan M, Goodkin K, et al. Prolonged grief disorder: psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000121. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121.

Lundorff M, Holmgren H, Zachariae R, Farver-Vestergaard I, O'Connor M. Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;212:138–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.030.

Keyes KM, Pratt C, Galea S, McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Shear K. The burden of loss: unexpected death of a loved one and psychiatric disorders across the life course in a National Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014:864–71.

Ott CH, Lueger RJ, Kelber ST, Prigerson HG. Spousal bereavement in older adults: common, resilient, and chronic grief with defining characteristics. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:332–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000243890.93992.1e.

Kersting A, Brähler E, Glaesmer H, Wagner B. Prevalence of complicated grief in a representative population-based sample. J Affect Disord. 2011;131:339–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.032.

Caserta MS, Utz RL, Lund DA. Spousal bereavement following cancer death. Illn Crises Loss. 2013;21:185–202. https://doi.org/10.2190/IL.21.3.b.

Stewart BW, Wild CP, editors. World cancer report 2014. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014.

Robert Koch-Institut. Bericht zum Krebsgeschehen in Deutschland 2016. Berlin; 2016.

Tan J-Y, Molassiotis A, Lloyd-Williams M, Yorke J. Burden, emotional distress and quality of life among informal caregivers of lung cancer patients: an exploratory study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12691. Epub 2017 Apr 18.

Friðriksdóttir N, Saevarsdóttir T, Halfdánardóttir SÍ, Jónsdóttir A, Magnúsdóttir H, Olafsdóttir KL, et al. Family members of cancer patients: needs, quality of life and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:252–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2010.529821.

Ellis J. The impact of lung cancer on patients and carers. Chron Respir Dis. 2012;9:39–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1479972311433577.

Hodges LJ, Humphris GM, Macfarlane G. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.018.

Langer S, Lehane C, Yi J. Patient and caregiver adjustment to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a systematic review of dyad-based studies. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11899-017-0391-0.

Molassiotis A, Wilson B, Blair S, Howe T, Cavet J. Unmet supportive care needs, psychological well-being and quality of life in patients living with multiple myeloma and their partners. Psychooncology. 2011;20:88–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1710.

Pitceathly C, Maguire P. The psychological impact of cancer on patients’ partners and other key relatives. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1517–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00309-5.

Douglas SL, Daly BJ, Lipson AR. Relationship between physical and psychological status of cancer patients and caregivers. West J Nurs Res. 2016;38:858–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945916632531.

Wulff-Burchfield EM, Jagasia M, Savani BN. Long-term follow-up of informal caregivers after allo-SCT: a systematic review. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:469–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2012.123.

Albrecht TA, Rosenzweig M. Management of Cancer Related Distress in patients with a hematological malignancy. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2012;14:462–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0b013e318268d04e.

Manitta V, Zordan R, Cole-Sinclair M, Nandurkar H, Philip J. The symptom burden of patients with hematological malignancy: a cross-sectional observational study. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2011;42:432–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.12.008.

Tanimukai H, Hirai K, Adachi H, Kishi A. Sleep problems and psychological distress in family members of patients with hematological malignancies in the Japanese population. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:2067–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-014-2139-4.

Beattie S, Lebel S. The experience of caregivers of hematological cancer patients undergoing a hematopoietic stem cell transplant: a comprehensive literature review. Psychooncology. 2011;20:1137–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1962.

Kim Y, Shaffer KM, Carver CS, Cannady RS. Quality of life of family caregivers 8 years after a relative's cancer diagnosis: follow-up of the National Quality of life survey for caregivers. Psychooncology. 2016;25:266–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3843.

Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, Onelöv E, Henter J-I, Steineck G. Anxiety and depression in parents 4–9 years after the loss of a child owing to a malignancy: a population-based follow-up. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1431. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291704002740.

Song JI, Shin DW, Choi J-Y, Kang J, Baek Y-J, Mo H-N, et al. Quality of life and mental health in the bereaved family members of patients with terminal cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21:1158–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.2027.

Garrido MM, Prigerson HG. The end-of-life experience: modifiable predictors of caregivers' bereavement adjustment. Cancer. 2014;120:918–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28495.

Nielsen MK, Neergaard MA, Jensen AB, Vedsted P, Bro F, Guldin M-B. Predictors of complicated grief and depression in bereaved caregivers: a Nationwide prospective cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;53:540–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.09.013.

Jalmsell L, Onelöv E, Steineck G, Henter J-I, Kreicbergs U. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children with cancer and the risk of long-term psychological morbidity in the bereaved parents. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46:1063–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2010.287.

Lange A, van de Ven J-P, Schrieken B, Emmelkamp PMG. Interapy. Treatment of posttraumatic stress through the internet: a controlled trial. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2001;32:73–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7916(01)00023-4.

Lange A, Rietdijk D, Hudcovicova M, van de Ven J-P, Schrieken B, Emmelkamp PMG. Interapy: a controlled randomized trial of the standardized treatment of posttraumatic stress through the internet. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:901–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.901.

Aboujaoude E, Salame W, Naim L. Telemental health: a status update. World Psychiatry. 2015;14:223–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20218.

Musiat P, Tarrier N. Collateral outcomes in e-mental health: a systematic review of the evidence for added benefits of computerized cognitive behavior therapy interventions for mental health. Psychol Med. 2014;44:3137–50. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714000245.

Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38:196–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070903318960.

Dölemeyer R, Klinitzke G, Steinig J, Wagner B, Kersting A. Die therapeutische Beziehung in einem internetbasierten Programm zur Behandlung der Binge-Eating-Störung. Psychiatr Prax. 2013;40:321–6. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1343320.

Wagner B, Brand J, Schulz W, Knaevelsrud C. Online working alliance predicts treatment outcome for posttraumatic stress symptoms in Arab war-traumatized patients. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:646–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.21962.

Knaevelsrud C, Böttche M, Pietrzak RH, Freyberger HJ, Renneberg B, Kuwert P. Integrative testimonial therapy: an internet-based, therapist-assisted therapy for German elderly survivors of the world war II with posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:651–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000178.

Klein B, Mitchell J, Abbott J, Shandley K, Austin D, Gilson K, et al. A therapist-assisted cognitive behavior therapy internet intervention for posttraumatic stress disorder: pre-, post- and 3-month follow-up results from an open trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:635–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.04.005.

Northouse L, Williams A-L, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1227–34. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798.

Boelen PA, de Keijser J, van den Hout MA, van den Bout J. Treatment of complicated grief: a comparison between cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:277–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.277.

Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, Reynolds CF. Treatment of complicated grief: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2601–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.21.2601.

Wagner B, Knaevelsrud C, Maercker A. Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for complicated grief: a randomized controlled trial. Death Stud. 2006;30:429–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180600614385.

Kersting A, Dölemeyer R, Steinig J, Walter F, Kroker K, Baust K, Wagner B. Brief internet-based intervention reduces posttraumatic stress and prolonged grief in parents after the loss of a child during pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2013;82:372–81. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348713.

Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF III, Bierhals AJ, Newsom JT, Fasiczka A, et al. Inventory of complicated grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59:65–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2.

Rosner R, Pfoh G, Kotoučová M. Diagnose der anhaltenden Trauerstörung mit der deutschen Version des PG-13 [Diagnosing prolonged grief disorder with the German version of the PG-13]. In: Rosner R, Pfoh G, Rojas R, Brandstätter M, Rossi R, Lumbeck G, et al., editors. Anhaltende Trauerstörung: Manuale für die Einzel- und Gruppentherapie: Hogrefe Verlag; 2015. p. 27–9.

Wagner B, Knaevelsrud C, Maercker A. Internet-based treatment for complicated grief: concepts and case study. J Loss Trauma. 2005;10:409–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020590956828.

Wagner B, Lange A. Internetbasierte Psychotherapie "Interapy". In: Bauer S, Kordy H, editors. E-Mental-Health: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2008. p. 105–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-75736-8%5F9.

Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Measuring emotion: the self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1994;25:49–59.

Spitzer RL. Validation and Utility of a Self-report Version of PRIME-MD. The PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.18.1737.

Tracey TJ, Kokotovic AM. Factor structure of the working alliance inventory. Psychol Assess. 1989;1:207–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.1.3.207.

Lumbeck G, Brandstätter M, Geissner E. Erstvalidierung der deutschen Version des Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG-D). Z Klin Psychol Psychother (Gott). 2012;41:243–8. https://doi.org/10.1026/1616-3443/a000172.

Xiu D, Maercker A, Woynar S, Geirhofer B, Yang Y, Jia X. Features of prolonged grief symptoms in Chinese and Swiss bereaved parents. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016;204:693–701. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000539.

Lange A, Schrieken B, Blankers M, van de Ven J-P, Slot M. Constructie en validatie van de Gewaarwordingenlijst: Een hulpmiddel bij het signaleren van een verhoogde kans op psychosen*. Dth. 2000;20:82–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03060234.

Manicavasagar V, Silove D, Wagner R, Drobny J. A self-report questionnaire for measuring separation anxiety in adulthood. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44:146–53. https://doi.org/10.1053/comp.2003.50024.

Barry LC. Psychiatric disorders among bereaved persons: the role of perceived circumstances of death and preparedness for death. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:447–57. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajgp.10.4.447.

Bailley SE, Dunham K, Kral MJ. Factor structure of the grief experience questionnaire (GEQ). Death Stud. 2000;24:721–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811800750036596.

Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK. Prolonged grief disorder (PG-13). Dana-Farber Cancer Institute: Boston, MA; 2006.

Löwe B, Spitzer RL, Zipfel S, Herzog W. Gesundheitsfragebogen für Patienten (PHQ D). Komplettversion und Kurzform. 2nd ed.: Pfizer; 2002.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Gräfe K, Zipfel S, Herzog W, Löwe B. Screening psychischer Störungen mit dem Gesundheitsfragebogen für Patienten (PHQ-D). Diagnostica. 2004;50:171–81. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924.50.4.171.

Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The impact of event scale - revised. In: Wilson J, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Guilford; 1997. p. 399–411.

Maercker A, Schützwohl M. Erfassung von psychischen Belastungsfolgen: die impact of event Skala-revidierte version (IES-R). [assessment of post-traumatic stress reactions: the impact of event scale-revised (IES-R).]. Diagnostica. 1998;44:130–41.

Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the scale for suicide ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47:343–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.47.2.343.

Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Kognitive Therapie der depression. München: Urban & Schwarzenberg; 1981.

Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA. Psychometric characteristics of the scale for suicide ideation with psychiatric outpatients. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:1039–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00073-9.

Nijenhuis ERS, Spinhoven P, Dyck R, Hart O, Vanderlinden J. The development of the somatoform dissociation questionnaire (SDQ-5) as a screening instrument for dissociative disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;96:311–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09922.x.

Mueller-Pfeiffer C, Schumacher S, Martin-Soelch C, Pazhenkottil AP, Wirtz G, Fuhrhans C, et al. The validity and reliability of the German version of the somatoform dissociation questionnaire (SDQ-20). J Trauma Dissociation. 2010;11:337–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299731003793450.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–7.

Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, Herzberg PY. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46:266–74.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33.

Bullinger M, Kirchberger I, Ware J. Der deutsche SF-36 Health Survey Übersetzung und psychometrische Testung eines krankheitsübergreifenden Instruments zur Erfassung der gesundheitsbezogenen Lebensqualität. Z Gesundh Wiss. 1995;3:21.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213.

Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, Riemann D, Hohagen F. Test–retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index in primary insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:737–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00330-6.

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9:455–71.

Maercker A, Langner R. Persönliche Reifung (Personal Growth) durch Belastungen und Traumata. Diagnostica. 2001;47:153–62. https://doi.org/10.1026//0012-1924.47.3.153.

Boelen PA, van den Bout J. Anxious and depressive avoidance and symptoms of prolonged grief, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Belg. 2013;50:49. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb-50-1-2-49.

Holland JC, Kash KM, Passik S, Gronert MK, Sison A, Lederberg M, et al. A brief spiritual beliefs inventory for use in quality of life research in life-threatening illness. Psychooncology. 1998;7:460–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199811/12)7:6<460::AID-PON328>3.0.CO;2-R.

Albani C, Bailer H, Blaser G, Geyer M, Brahler E, Grulke N. Religious and spiritual beliefs - validation of the German version of the "Systems of Belief Inventory" (SBI-15R-D) by Holland et al. in a population-based sample. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2002;52:306–13. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-32863.

Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:226–44.

Doll J, Mentz M, Witte EH. Zur Theorie der vier Bindungsstile: Meßprobleme und Korrelate dreier integrierter Verhaltenssysteme [the theory of four attachment styles: problems of measurement and correlations of three integrated behavioural systems]. Z Sozialpsychol. 1995:148–59.

Pierce GR, Sarason IG, Sarason BR. General and relationship-based perceptions of social support: are two constructs better than one? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:1028–39.

Reiner I, Beutel M, Skaletz C, Brähler E, Stöbel-Richter Y. Validating the German version of the quality of relationship inventory: confirming the three-factor structure and report of psychometric properties. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37380. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037380.

Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:169–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0.

Wingenfeld K, Spitzer C, Mensebach C, Grabe HJ, Hill A, Gast U, et al. Die deutsche Version des Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ): Erste Befunde zu den psychometrischen Kennwerten. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2010;60:e13. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1253494.

Klinitzke G, Romppel M, Häuser W, Brähler E, Glaesmer H. Die deutsche Version des Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) - psychometrische Eigenschaften in einer bevölkerungsrepräsentativen Stichprobe. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2012;62:47–51. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1295495.

Schwarzer R, Schulz U. Berliner Social-Support Skalen (BSSS). 2000. http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/soc_g.htm. Accessed 27.07.17.

Schulz U, Schwarzer R. Soziale Unterstützung bei der Krankheitsbewältigung: Die Berliner Social Support Skalen (BSSS). Diagnostica. 2003;49:73–82. https://doi.org/10.1026//0012-1924.49.2.73.

Blatt SJ, D’Aflitti JP, Quinlan DM. Depressive Experiences Questionnaire. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1979.

Beutel ME, Wiltink J, Hafner C, Reiner I, Bleichner F, Blatt S. Abhängigkeit und Selbstkritik als psychologische Dimensionen der Depression - Validierung der deutschsprachigen Version des Depressive Experience Questionnaire (DEQ). Z Klin Psychol Psychiatr Psychother. 2004;

Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image: Princeton university press Princeton, NJ; 1965.

von Collani G, Herzberg PY. Eine revidierte Fassung der deutschsprachigen Skala zum Selbstwertgefühl von Rosenberg. Zeitschrift für Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychologie. 2003;24:3–7. https://doi.org/10.1024//0170-1789.24.1.3.

Jerusalem M, Schwarzer R. SWE - Skala zur Allgemeinen Selbstwirksamkeitserwartung: ZPID (Leibniz Institute for Psychology Information); 1981.

Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4:92–100. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6.

Knoll N, Rieckmann N, Schwarzer R. Coping as a mediator between personality and stress outcomes: a longitudinal study with cataract surgery patients. Eur J Pers. 2005;19:229–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.546.

Wilmers F, Munder T. Die deutschsprachige Version des Working Alliance Inventory – short revised (WAI-SR) – Ein schulenübergreifendes, ökonomisches und empirisch validiertes Instrument zur Erfassung der therapeutischen Allianz. Klinische Diagnostik & Evaluation 2008.

Acknowledgements

This study is conducted at the Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy (Prof. Dr. med. Anette Kersting, PI) in cooperation with the Department of Medical Psychology and Medical Sociology (Prof. Dr. phil. Anja Mehnert) and the Department of Haematology and Medical Oncology (Prof. Dr. med. Dr. h. c. Dietger Walter Niederwieser), University Medical Centre Leipzig.

Funding

The study is funded by “Deutsche José Carreras Leukämie-Stiftung” (German José Carreras Leukemia Foundation, DJCLS R15/22), which had no role in the design of this study and has no role in its execution, analysis and interpretation of data, or publication of results. The authors acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and Universität Leipzig within the program of Open Access Publishing.

Availability of data and materials

Anonymized data gathered and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to legal and ethical restrictions but can be requested from the corresponding author. Text material of therapies is not publicly available due to legal restrictions and cannot be made available at any time.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RH and JG are main contributors to the concept and writing of the study protocol. MN, AM and AK are main contributors to the concept of the study itself, raised third-party funds for the study and contributed to literature analyses and writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The presented study has been approved by the University of Leipzig ethics committee (No. 450–15-21,122,015 (20.01.17), 450/15-ff (13.10.17), 450/15-ek (20.12.17)).

Prior to study participation, all patients receive written information in the Participant Information Sheet about the content and extent of the planned study and the intervention. Persons who agree to participate are required to sign the informed consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoffmann, R., Große, J., Nagl, M. et al. Internet-based grief therapy for bereaved individuals after loss due to Haematological cancer: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 18, 52 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1633-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1633-y