Abstract

Background

Limited evidence exists regarding fitness-to-drive for people with the mental health conditions of schizophrenia, stress/anxiety disorder, depression, personality disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder (herein simply referred to as ‘mental health conditions’). The aim of this paper was to systematically search and classify all published studies regarding driving for this population, and then critically appraise papers addressing assessment of fitness-to-drive where the focus was not on the impact of medication on driving.

Methods

A systematic search of three databases (CINAHL, PSYCHINFO, EMBASE) was completed from inception to May 2016 to identify all articles on driving and mental health conditions. Papers meeting the eligibility criteria of including data relating to assessment of fitness-to-drive were critically appraised using the American Academy of Neurology and Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine protocols.

Results

A total of 58 articles met the inclusion criteria of driving among people with mental health conditions studied, and of these, 16 contained data and an explicit focus on assessment of fitness-to-drive. Assessment of fitness-to-drive was reported in three ways: 1) factors impacting on the ability to drive safely among people with mental health conditions, 2) capability and perception of health professionals assessing fitness-to-drive of people with mental health conditions, and 3) crash rates. The level of evidence of the published studies was low due to the absence of controls, and the inability to pool data from different diagnostic groups. Evidence supporting fitness-to-drive is conflicting.

Conclusions

There is a relatively small literature in the area of driving with mental health conditions, and the overall quality of studies examining fitness-to-drive is low. Large-scale longitudinal studies with age-matched controls are urgently needed in order to determine the effects of different conditions on fitness-to-drive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

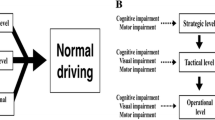

The ability to drive enables access to the community, services, friends and family, and therefore promotes autonomy and social connectivity [1, 2]. Driving is a complex task that demands a wide range of skills, abilities and behaviours [3]. Driving involves physical, cognitive, and perceptual skills, along with the ability to respond to the external environment. Driving can be influenced by extent of past experience and personality characteristics [4]. There is considerable debate about the driving ability of people with mental health conditions. The fitness-to-drive of people with mental health conditions may vary within individuals due to both the effects of the illness itself, as well as the impact of psychiatric drugs on driving performance. Individuals diagnosed with mental health conditions may experience reduced attention, visual spatial functioning, impulse control, judgement, as well as alterations in information processing ability and slowed psychomotor reaction times [5,6,7]. These difficulties can all impair driving abilities [8, 9] and may lead to a recommendation not to drive, a restricted driving licence, driving suspension or licence cancellation [10]. It is important that any restriction is based on evidence to the greatest extent possible, and reflects a due balance between mobility and safety [11] as driving cessation is associated with increased levels of depression [12].

The proportion of individuals with mental health conditions who drive is unknown. However, it is believed that a significant proportion of people are driving, and able to do so safely. For example, 44% of people with mental health conditions from regional and 35% from metropolitan areas in Australia were reported as active drivers [13]. Some studies [14,15,16] suggest that drivers with mental health conditions have a higher risk of being involved in a crash. However, assessment to determine fitness-to-drive of individuals with mental health conditions is difficult because of the fluctuating nature of impairments, skills and behaviours [17,18,19]. Currently, there is no single assessment that can be used to accurately predict driving ability of people with mental health conditions [20]. Instead, medical and occupational therapy assessments, neuropsychological tests, and performance based assessments such as on-road assessment and car driving simulator tests are commonly used to determine if a person is fit-to-drive. However, medical guidelines have been developed internationally, and are regularly updated, to assist health professionals in determining fitness-to-drive. These medical guidelines can be used to provide recommendations on licence renewal, suspension or cancellation for clients with mental health conditions. Existing guidelines include those produced by the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) in the UK [21], the New Zealand Transport Agency [22], the Irish Road Safety Authority [23], Austroads in Australia [10], Driver Fitness Medical Guidelines in the USA [24] and the Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators [25]. While all these provide general information on health conditions as well as guidance and recommendations on assessing fitness-to-drive, only the DVLA [21] guidelines provide clear and detailed recommendations on minimum stand-down periods from driving relating to various psychiatric conditions although the evidence base for these recommendations is unknown, as is the extent to which clinicians comply with them.

The driving literature is dominated by research investigating the impact of physical and cognitive problems arising from dementia and acquired disorders such as brain injury (including stroke), on driving. While there is a growing literature on the impact of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder on driving, evidenced by several systematic review [26,27,28,29,30], only two literature reviews summarising evidence of fitness-to-drive and the mental health conditions of schizophrenia, stress/anxiety disorder, depression, personality disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder have been published [31, 32]. Tsuang, Boor, and Fleming (1985) [31] reviewed the literature in order to identify risk factors related to psychopathology and personality variables for crashes. The authors suggested that the studies reviewed were insufficiently homogenous to understand these relationships. A subsequent systematic review conducted by Menard and Korner-Bitensky (2008) [32] sought to identify and appraise published studies on fitness-to-drive amongst people with mental health conditions and the effect of psychotropic medications on driving performance. This review included 14 studies, all published before 1990. The authors concluded that there was no consistent evidence to support the hypothesis of an increased crash rate amongst drivers with severe mental health conditions. For those with milder or better controlled mental health conditions, conclusions were more difficult to draw given contradictory evidence about fitness-to-drive. Since it was assumed that many new studies would have been published on the topic of mental health and driving since 1990, it was timely to review this literature and appraise current evidence regarding the fitness-to-drive with this population.

We specifically aimed to critically appraise literature on driving among people with the mental health conditions of schizophrenia, stress/anxiety disorder, depression, personality disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder, as anecdotally clinicians most frequently ask us questions about these groups. However, we also made the decision to exclude driving literature with these populations when the focus was specifically on the impact of medication on driving given the estimated size of this literature would require a separate review and our primary interest was in how the medical conditions impact on driving, regardless of pharmacological interventions. We were particularly influenced by the fact that many clients are stable on medication when driving is reviewed, and also the growing literature which suggests that skills for driving may be impaired in people with mental health conditions, and this decrement is not related to the effects of medications [6, 17]. In addition, we did not include literature that examined the driving of people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Although many of the mental health conditions included in this review such as anxiety, depression, or personality disorder, are commonly comorbid to ADHD, we chose to exclude this literature based again on its size and that five systematic reviews have already summarised this literature [26,27,28,29,30]. However, it is important to note that many of the problems experienced by people with mental health conditions that may impair driving, such as impulsivity, reduced response inhibition, reduced situational awareness, and the fluctuating nature of the condition, are also experienced by people with ADHD [27]. Therefore, the Discussion section does make reference to this literature.

Aim

The broad aim of this systematic review was to identify what is known about driving for people with mental health conditions, and critically appraise studies that empirically investigated assessment of fitness-to-drive among people with mental health conditions. Specifically the review aimed to answer the questions:

-

1.

What is the scope of published literature on the topic of mental health and driving (excluding drivers with ADHD), and

-

2.

What is the scope and quality of empirical studies addressing assessment of fitness-to drive among people with mental health conditions, where the focus is not on the impact of medication on driving.

Methods

This systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines [33], and the protocol for this review is available from the corresponding author.

Search strategy

Three electronic databases (CINAHL, PSYCHINFO, EMBASE) were used to identify articles from inception to 10th May, 2016. Extensive search terms were identified and used to reduce the risk of missing relevant studies. Search terms included: automobile driv*, driv* ability, driv* competence, driv* perform*, driv* skill, fit*to driv*, AND affective, alcohol abus*, alcohol dependence, alcohol misuse*, alcohol use*, anxiet*, anxious, bipolar disorder, delusion, depress*, drug abus*, drug dependence, drug misuse, drug use*, mania, manic, mental disab*, mental disorder*, mental health, mental ill* disab*, mental ill*, mental* health disorder, mood, neuroses, neurosis, neurotic, obsessive* compulsive, OCD, panic, personality disorder*, phobia, psychiatric, psychiatry, psychology*, psychos*, psychotic, schizophreni*, schizotyp*, somatic, somatoform, stress, substance abus*, substance dependence, substance misuse, substance related disorder*, substance use*, and suicid*. The Search terms ‘antidepressant’, ‘anxiolytic’, ‘antipsychotic’ and ‘mood-stabilizer’ were also exploded and used to search for relevant studies. Citations of retrieved studies were exported into EndNote version ×7, and duplicate studies deleted. Reference lists of included articles were subsequently checked for additional articles of interest, and keywords searched on journal articles to obtain relevant studies.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for identification of all articles on driving with a mental health condition are presented in Table 1. The primary interest of this review focussed on people diagnosed with schizophrenia, stress/anxiety disorder, depression, personality disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder. Studies on sleep disorders, drugs and alcohol misuse and dependence, attention deficit and hyperactivity syndrome and mood/anger/aggression where a specific mental health condition was not identified, were excluded.

Two authors (CU and MS) independently screened titles and abstracts of all identified studies, and excluded ineligible studies against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Disagreements among authors were resolved by discussion and achieving consensus. Full copies of studies were obtained to determine eligibility of articles that were hard to identify solely based on titles and abstracts.

Quality assessment/evidence based ratings

The classification criteria developed by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) [34] and by the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) [35] were used to assign the class or level to rate the strength of evidence, and to assess the quality of the included studies. According to the CEBM, there are five levels of evidence, ranging from I to V (indicating highest to lowest). The AAN presents a system of rating an article by class. The highest evidence is represented by class I and the lowest is represented by class IV (presented in Table 2). Following these criteria, two authors (CU and MS) independently assessed the quality of articles. Again, disagreements were resolved by discussion and achieving consensus.

Data extraction

Data were synthesised qualitatively, by using a narrative analysis. This method of analysis involved coding information from within individual studies and grouping them into like categories, based on the data provided and the findings of the analysis. Where there was over-lap in information and a study could potentially have been included under more than one of the categories, the study was allocated to the category for which the most data had been provided. Two authors (CU and MS) independently completed data extraction. Publication details, aims of the study, participant details, study design and findings related to the assessment of fitness-to-drive were extracted, summarised and presented in a table format.

Results

A total of 94 studies were identified after the removal of duplicates (see Fig. 1), and initial screening process. For Aim 1 identifying peer-reviewed, published literature on the topic of mental health and driving, 58 studies were identified and categorised into six subgroups:

1) role of psychotropic drugs on driving ability (n = 24), 2) guidelines/editorials/discussion pieces on the current status of drivers with mental health conditions (n = 11), 3) driving phobia/anxiety and veterans with PTSD (n = 7), 4) fitness-to-drive of people with mental health conditions (n = 14), 5) subjective experiences of driving (and fitness-to-drive assessment) with a mental health condition (n = 1), and 6) health professionals’ role in assessment of fitness-to-drive (n = 1). Further analyses of data from subgroups 1, 2, and 3 were not completed beyond categorising the scope and volume of the literature in this area. The citations for these studies can be viewed in Additional file 1.

For Aim 2 the authors’ critically appraised studies that included data related to assessing fitness-to-drive. Research that primarily focussed on the role of psychotropic drugs, driving phobia/anxiety and veterans with PTSD, and guidelines/editorials/discussion pieces were excluded. While literature focussing on the role of psychotropic drugs is very valuable to understanding fitness to drive, this is a large literature that requires a separate review and detailed background on the medications and their actions and effects in a typical populations as well as populations with mental health problems. The other areas of driving phobia/anxiety and veterans with PTSD, and guidelines/editorials/discussion pieces were excluded as these subgroups did not meet the aim of containing sufficient data related to assessing fitness-to-drive among people with mental health conditions. Fifteen studies were retained for review in Aim 2. As presented in Table 3, three of the 16 included studies were classified as Class III, 12 were classified as Class IV, and one was unclassified since it was secondary analysis of medical records. Under the CEBM classification criteria, the review yielded seven level 4 studies and eight level 5 studies, with the same paper again as unclassified. Among these studies, the majority (n = 5) were conducted in Canada. Other studies were conducted in Germany, Ireland, Switzerland, Spain, Denmark and America.

The 16 studies were re-classified based on the data each study provided about assessing fitness-to-drive as follows: 1) factors impacting on the ability to drive safely among people with mental health conditions (n = 7) [8, 36,37,38,39,40,41] capability and perception of health professionals assessing fitness-to-drive of people with mental health conditions (n = 5) [42,43,44,45,46] and 3) crash rates (n = 4) [47,48,49,50].

Factors impacting on the ability to drive safely among people with mental health conditions.

For those with major depressive disorder, Bulmash et al. [8] found that people with depression, even when not on anti-depression medication, experienced higher levels of sleepiness when driving. This was found to impact their capacity to maintain appropriate speed when driving in a simulator. In addition, it was found that people with depression showed a significantly slower steering reaction time, and a greater number of crashes, as compared to controls. The level of slowed reaction time was not related to the level of severity of symptoms. When not sleepy, road position, speed and speed deviation were no different to those of controls. The association with depression was therefore apparent, even when participants were not on medication, and seemed to manifest itself when sleepiness was experienced in this study.

For those with bi-polar disorder who had committed driving offences, Zingg, Puelschen, and Soyka [41] found that drivers had impairments in problem solving and cognitive flexibility, alertness, and visual scanning/reaction time. It was noted that these signs and symptoms may have been caused by the clinical condition itself, or by medication taken for the condition in this study. Additionally, although information processing ability was found to be impaired in those with bi-polar disorder, this was no more so than in those who had committed driving offences, and who did not have a psychiatric condition. From this study it was suggested that a bi-polar disorder did not appear to have impaired information processing ability specifically. Decrements in psychomotor skill were also reported among people with schizophrenia by Segmiller et al. [40]. However, they demonstrated that reduced skill was not related to medication side effects.

For those in manic and hypomanic states, McNamara and Buckley [38] found that some participants reported speeding, making poor decisions, losing the feeling of control, decreased concentration and judgement, and impulsivity. As some participants reported that they felt their medical condition did not impair their driving ability, as compared with the general population, lack of insight among participants was also apparent in this study. Although participants reported that having an open communication with health professionals about their driving was helpful, they perceived fitness-to-drive guidelines as discriminatory. The underlying signs of grandeur and lack of insight characteristic of hypomanic and manic states among these participants would fit with this lack of capacity to recognise the gravity of risk to themselves and others, and the potential to feel the guidelines were not respectful of their standing.

In the most recent study by Brunnauer et al. [36], the authors explored the impact of mental illness on driving licence possession and driving restrictions. Higher educational status and being partnered or in a relationship was a key predictor for having a driving licence. People with mental health conditions were also found to be less likely to hold a driving licence or to be currently driving, as compared with controls, particularly for those with organic mental and psychotic disorders.

Capability and perception of health professionals assessing fitness-to-drive of people with mental health conditions

As can be seen in Table 3, Subgroup 2, the majority of studies examining health professionals’ assessment of fitness-to-drive were conducted in Canada, with the remaining few studies being conducted in the Republic of Ireland. The studies examined attention to the mental health condition and its impact on fitness-to-drive, and the nature and occurrence of recording of such factors in the medical notes. Variations in differing health professionals’ foci of interest were also investigated with all studies being exploratory and qualitative in nature.

Crash rates

Crancer and Quiring [47] conducted the earliest studies examining the link between mental illness and limitations in driving capacity. They identified that those with psychotic disorders, personality disorders and psychoneurotic disorders had higher rates of reckless driving, negligent driving and driving with defective equipment. Other studies undertaking epidemiological secondary data analysis showed that crashes were more prevalent among people with mental health conditions and that the injuries sustained are more serious, with someone with a mental health condition being more likely to be hospitalised than those without [49]. With regards to the diagnostic groups in these studies, in the second stage analysis of the study conducted by Kastrup, Dupont, Bille, and Lund [50], the most common diagnostic group was found to be personality disorder. The drivers with psychiatric diagnosis were found to be characterised by women, aged 25–54 years. They were more frequently alcohol intoxicated, and with a higher blood alcohol level. They were found to be more likely to be driving a stolen vehicle, without a valid licence, and were found not to have used safety belts at the time of the crash. From this study it appears that those with personality disorders are having crashes due to the behavioural manifestations of their condition; that is, they undertake risky behaviours that impact on their ability to drive safely. Elkema, Brosseau, Koshnick, and McGee [48] also reported the highest crash rate of those with mental health conditions was those with personality disorders. In this study, it was noted that the behavioural traits demonstrated by those with personality disorders were very different in substance to those with significant mental illness due to depression and bi-polar disorders, associated with an impairment of executive level function.

Discussion

The discussion presents an overview of the findings in relation to the two aims, as well as considering limitations of this systematic review and directions for further research. Initially, this systematic review sought to identify and categorise all peer-reviewed, published literature on the topic of mental health and driving. A relatively small literature was identified, with the largest category related to the impact of psychotropic drugs on driving ability. The second largest category of papers related to assessment of fitness-to-drive, and this topic was further explored in relation to ‘impact of specific mental health conditions on the ability to drive safely’, ‘health professionals’ role in assessing fitness-to-drive’, and ‘crash statistics’.

Impact of specific mental health conditions on the ability to drive safely

Research to date appears to suggest that the behavioural, cognitive and psychomotor impairments that reduce fitness-to-drive may differ between different diagnostic groups. Crancer and Quiring [47] conducted one of the earliest studies on the link between mental health conditions and driving capacity, associating psychotic disorders, personality disorders and psychoneurotic disorders with impaired fitness-to-drive. Due to the age of this study, these findings may need to be reinvestigated as improvements in medication and healthcare for people with these conditions may alter the findings. However, in a recent study Segmillar et al. [40], also found patients with schizophrenia had impaired psychomotor function that could not be attributed to side effects of psychopharmacological treatment, although no chronological decline was found in the early stages of the disease. Similarly, Brunnauer and Laux [51] concluded that even when stabilised with antipsychotic medication, a great proportion of schizophrenic patients are not fit to drive.

For those with major depressive disorder, Bulmash et al. [8] reported higher levels of sleepiness when driving, irrespective of medication use. Similarly, Wingen et al. [9] also concluded that impaired driving performance in this population is probably not due to antidepressant medications. This finding of a high level of sleepiness suggests that behavioural approaches to keep alertness levels higher may need to be considered, such as shortening routes, not eating a heavy meal before driving, and having a caffeine drink half an hour before driving. These interventions could be tested in a simulator experiment to see which elements are most effective for people with major depressive disorders. When comparing the results from Bulmash et al. [8] and Zingg, Puelschen, and Soyka [41], it appears that major depressive disorder is associated with a more widespread impact on the skills needed for driving than those with bi-polar disorder. Zingg, Puelschen, and Soyka [41] found that bi-polar disorder did not impair information processing and driving ability specifically; but rather that poor information processing maybe an underlying weakness of those who commit driving offences. This hypothesis could be researched by introducing information processing testing as part of a standard driving test, and then conducting prospective research to determine the threshold that relates to safe driving.

Another issue raised for drivers with bi-polar disorder relates to self-insight, which resonates with the view of those with bi-polar disorder feeling that the fitness-to-drive guidelines are discriminatory. Reduced self-insight is of real concern for drivers in hypomanic and manic states, who may have ideas of grandeur and reduced self-regulation. Reduced self-insight and self-regulation may be an issue for those with bi-polar disorder requiring further attention in this population specifically, as these capacities do not appear to be impaired by all mental health conditions. The self-report of symptoms affecting capacity to drive identified by Rouleau, Mazer, Menard, and Maryse [45] matched some of those factors measured in a driving simulator, in that people with mental health conditions (predominantly mood disorders) recognised that their condition and medication caused them to have poor concentration, fatigue, dizziness, and sometimes feelings of aggression and nervousness. They reported being more careful when driving or not driving at all when experiencing these symptoms. For those individuals with a mental health condition currently not driving, even though they possess a licence, this suggests a component of self-regulation. The evidence presented by De Las Cuevas and Sanz [37] supported the fact that some drivers with mental health conditions do self-regulate, but only up to a point, since none of the drivers reported their mental health condition to licensing authorities. The issue of non-reporting may be linked with reduced insight about the need to do so or with the associated fear of licence suspension or cancellation.

Health professionals’ role in assessing fitness-to-drive

Alongside licensing authorities, medical professionals, occupational therapists and psychologists are involved in licensing decisions for drivers with mental health conditions. Menard et al. [43] found that only one quarter of psychiatrists felt skilled in making fitness-to-drive decisions. Half of these psychiatrists felt that people with mental health conditions were more likely to be involved in a crash. Studies have examined the rate of recording of assessment of fitness-to-drive by these professionals, as well as the documentation of advice on managing medication and its impact on driving. In one study, only half of those patients needing advice on the impacts of medication on their ability to drive, had this noted in their medical records. Additionally, there was minimal recording of how the mental health condition itself would impact on the patient’s driving capacity [42]. Over half of these psychiatrists said that they had advised on this issue, but it was not evident in the medical notes. Similar results were found by Menard et al. [43], who noted that psychiatrists were only aware of whether their patient was an active driver in a quarter of cases, and for these patients, psychiatrists were more likely to advise on medication impacts than effects of the medical condition. Rouleau, Mazer, Menard, and Maryse [45] also noted that psychiatrists paid attention to medication side effects on fitness-to-drive, alongside mood.

While psychiatrists may focus on the impact of medication on fitness-to-drive, occupational therapists are able to take clients for on-road driving tests and have been noted to emphasise the driver’s physical status, cognitive skills, impulsivity levels and driving history [44, 46] to assist determine fitness-to-drive. Focussing on impulsivity levels may be regarded as important, since impulsivity can be related to risk taking behaviours and difficulty self-regulating; characteristics present in the profile of those drivers most likely to crash [38, 48, 49]. Menard et al. [44] additionally found that occupational therapists paid attention to the client’s perception of their driving ability, factors impacting on their driving capabilities, and identifying goals related to driving. The emphasis was therefore on the person’s meta-cognitive functions related to self-regulation, risk taking behaviour and on-road driving ability, rather than on the effects of medication or the medical condition itself. Similar results were reported by Vrkljan, Myers, Blanchard, Crizzle, and Marshall [46], with occupational therapists in the study also in favour of the use of an on-road assessment to inform decision making in clients with a mental health conditions. The on-road assessment was used and seen by most participants as the most valid means of making fitness-to-drive recommendations, over-riding clinic-based test results (including simulation), in cases where the clinic-based test had indicated negative results. With clinic-based tests and simulation results lacking predictive validity when used alone [8], on-road assessment is important to consider with drivers with mental health conditions where there is a doubt about their capacity. As noted above, although literature on ADHD was not included in this review, Jerome et al.’s., [26] systematic review of the ADHD and driving literature also suggest that risk taking is an important area for further investigation. In particular, driving anger and aggression have been consistently associated with risky driving, and therefore health professionals can work off-road with clients to develop flexible strategies to better manage these emotions.

Crash statistics

A number of studies examining the correlation between mental health conditions and risk of crash have shown an association between significant mental illness and primarily higher level cognitive functions, when drivers were tested in a simulator. For example, Bulmash et al. [8] showed that those with major depressive disorders showed slower steering reaction times and a greater number of car crashes when compared to controls using a driving simulator. Driving simulation experiments appear to show that impaired executive functions impact on driving capacity, yet this is not always borne out in crash data held by licensing authorities [39]. One group that does seem to be over-represented in crash rate data, however, is those with personality disorders. Crancer and Quiring [47] confirmed variation in impairment and crash rates, due to diagnostic group. When compared to controls, statistically higher crash rates were identified in both the personality disorder group (114% higher) and in the psychoneurotic group (49% higher), whereas crash rates in the schizophrenic group were similar to the control group. Of note are the findings of Eelkema, Brosseau, Koshnick, and McGee [48] who showed that with treatment, crash rates decreased for all mental health conditions, apart from those with personality disorders. This is an interesting finding to compare against people with ADHD. While people with personality disorders and ADHD demonstrate several of the same traits such as inattentiveness and impulsiveness, in drivers with ADHD, the negative driving outcome are more focussed on driving violations and citations rather than crashes [26]. Approaches to improving safe driving behaviour in those with personality disorders and ADHD require further investigation.

Licensing authority actions concerning renewal, suspension, or cancellation of a person’s driving licence appear to be closely tied with evidence of crashes. Drivers who do not self-report mental health condition/s may come to the attention of licensing authorities after being involved in one or more crashes, and a relationship appears to exist between involvement in a crash and having a driving licence revoked among people with mental health conditions. However, this relationship may not be warranted. For example, in a case control study by Niveau and Kelley-Puskas [39], people reported to the authorities due to severity of psychiatric disease, were actually more likely to have a clean driving record in relation to crashes and violations than those who were not reported. Hence license revocation seemed to be due to the perceived severity of psychiatric disease itself rather than capacity to drive safely. The judgment of fitness-to-drive in this study was based on clinical or medical records, which is far less accurate that on-road assessments. As noted above, further studies investigating how fitness-to-drive recommendations are made for people with mental health conditions are warranted, and would reveal any inherent biases. Of course, licensing authority staff and health professional may always err on the side of caution, as although revoking a person’s driving licence can limit quality of life and subsequent health of the driver, this has to be balanced against allowing an unsafe driver to continue driving. The key is determining whether the driver with a mental health condition is any more unsafe than other drivers, and there is currently insufficient evidence to guide this decision.

Limitations and directions for future research

This systematic review was limited by the English language restriction imposed, as several studies published in other languages, such as German, could not be accessed. A meta analysis was not possible since studies were generally of low quality and heterogeneous in terms of aims and mental health conditions included. For example, while there is preliminary evidence to suggest that psychomotor skill levels and crash rates are different for populations of drivers with major depressive disorders, schizophrenia, bi-polar disorder and personality disorders, too few studies exist to allow for analyses and recommendations to be made. In contrast, such meta –analyses have been undertaken by pooling study data in the area of drivers with ADHD [26]. Future studies also require larger populations of each diagnostic group so that the impact of key variables on fitness-to-drive outcomes such as years of driving experience, medication use, and severity of the condition, can also be investigated. A systematic review of the 24 papers located that investigate the impact of medication use on drivers with mental health conditions is also required. This new review could also compare findings against comparable studies from the current review that did not specifically investigate the impact of medication on driving. The quality of future studies could also be increased by including age and sex-matched controls where possible, and the inclusion of longitudinal follow-up of people with mental health conditions who both do and don’t drive. It is generally the driver’s duty to report to the licensing authority any permanent or long-term condition which may impact on their fitness-to-drive. With regards to mental health conditions where a person’s insight may be affected, drivers may not be able to detect a problem and may continue to drive when they are not safe to do so. When individuals continue to drive when they are not fit to do so, this creates legal and ethical issues for treating health professionals, as well as the affected individual’s family.

This review has demonstrated that a number of health professionals feel ill-equipped to make fitness-to-drive recommendations for people with mental health conditions. General medical practitioners are expected to conduct assessments to identify individuals who may be unfit to drive, as well as to provide information to the driver licensing authority on an individual’s diagnosis, treatment and extent of impairment. Numerous studies have indicated that few general medical practitioners have any formal training, specific to fitness-to-drive [52,53,54], although a recent concerted national education programme on medical fitness to drive has proved effective for Irish general practitioners [55]. Furthermore, while specialist driver-assessor occupational therapists do play a role in assessing fitness-to-drive of a wide range of people with heath concerns and age-related health declines [55], the literature provides limited information about their attitudes, practices and knowledge regarding fitness-to-drive among individuals with mental health conditions [44]. Finally, it may be the case that recommendations of fixed time limits for driving cessation imposed on people with mental health conditions may be unrealistic, lack an evidence base and are possibly ignored by health professionals. Whether to suspend, cancel, renew, or issue a person’s driving licence has considerable impact on not only a person’s health, but also on the subsequent health and well-being of all road users. Currently, insufficient evidence exists to support fair and equitable decision making for fitness-to-drive among people with mental health conditions, and further research is required to support health professionals in this area.

Conclusions

This systematic review has identified a small and disjointed literature in the area of mental health conditions and driving. A narrative appraisal of literature in the area of assessment of fitness-to-drive revealed only 16 studies, excluding those papers focusing on the impact of medication on driving, from which conclusions cannot be reliably drawn. Some of the major limitations associated with these studies include small sample sizes with low numbers in specific diagnostic groups, and a lack of methodological control. Despite these shortcomings, the review indicated the main issues to be considered in relation to determining fitness-to-drive for people with mental health conditions are; the fluctuating nature of the condition and associated symptoms, driver level of insight, behaviour, increasing evidence suggesting a decrement of psychomotor and cognitive skills among people not related to medication use, and a lack of research evidence to support health professionals to make fitness-to-drive recommendations. In conclusion, this systematic review has identified some of the factors impacting on fitness-to-drive for individuals with mental health conditions as well as some predictors of crash. Further research is urgently required to longitudinally investigate skills among drivers from different diagnostic groups, determine strategies that can successfully assist drivers with mental health conditions to better self-regulate as their condition fluctuates, and support the capability of health professionals to assess fitness-to-drive of people with mental health conditions.

References

Golisz K. Occupational therapy interventions to improve driving performance in older adults: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2014;68:662–9.

Justiss MD. Occupational therapy interventions to promote driving and community mobility for older adults with low vision: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2013;67:296–302.

Fuller R. Towards a general theory of driver behaviour. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37:461–72.

Anstey KJ, Wood J, Lord S, Walker JG. Cognitive, sensory and physical factors enabling driving safety in older adults. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:45–65.

Hammar A, Lund A, Hugdahl K. Selective impairment in effortful information processing in major depression. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;65(2):234–47.

Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:426–45.

Purcell R, Maruff P, Kyrio M, Pantelis C. Neuropsychological function in young patients with unipolar major depression. Psychol Med. 1997;27(6):1277–85.

Bulmash EL, Moller HJ, Kayumov L, Shen J, Wang X, Shapiro CM. Psychomotor disturbance in depression: assessment using a driving simulator paradigm. J Affect Disord. 2006;93(1–3):213–8.

Wingen M, Ramaekers JG, Schmitt JA. Driving impairment in depressed patients receiving long-term antidepressant treatment. Psychopharmacology. 2006;188(1):84–91.

Austroads. Assessing fitness to drive: for commercial and private vehicle drivers. Australia: Sydney; 2016.

Oxley J, Whelan M. It cannot be all about safety: the benefits of prolonged mobility. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2008;9(4):367–78.

Chihuri S, Mielenz TJ, Dimaggio CJ, Betz ME, DiGuiseppi C, Jones VC, Li G. Driving cessation and health outcomes in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(2):332–41.

Rowse J (2010). Changing knowledge and practice: mental health service delivery and consumer fitness to drive. PhD thesis. La Trobe University, Australia.

Lam LT, Norton R, Connor J, Ameratunga S. Suicidal ideation, antidepressive medication and car crash injury. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37(2):335–9.

Sheridan MP. Assessing fitness to drive in dementia and other psychiatric conditions: a higher training learning opportunity at a driver assessment centre. Psychiatrist. 2012;36:113–6.

Waller JA. Chronic medical conditions and traffic safety: a review of the California experience. N Engl J Med. 1965;273:1413–20.

De Las Cuevas C, Ramallo Y, Sanz EJ. Psychomotor performance and fitness to drive: the influence of psychiatric disease and its pharmacological treatment. Psychiatry Res. 2010;176(2–3):236–41.

Dun C, Baker K, Swan J, Vlachou V, Fossey E. 'Drive safe' initiatives: an analysis of improvements in mental health practices (2005-2013) to support safe driving. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015;78(6):364–8.

Unsworth CA. Issues surrounding driving and driver assessment for people with mental health problems. Mental Health Occupational Therapy. 2010;15(2):41–4.

Unsworth CA, Baker A, Taitz M, Chan SP, Pallant JP, Russell K, Odell M. Development of a standardised Occupational Therapy - Driver Off-Road Assessment Battery to assess older and/or functionally impaired drivers. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2012;59(1):23-36.

Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) UK. (2016). Assessing fitness-to-drive- a guide for medical professional. Retrieved 21/12/16 from: www.gov.uk/dvla/fitnesstodrive

New Zealand Transport Agency. (2016). Medical aspects of fitness to drive. New Zealand transport agency. Retrieved 21/12/16 from: https://www.nzta.govt.nz/resources/medical-aspects/8.html

Road Safety Authority (2016). Sláinte agus Tiomáint: Medical Fitness to Drive Guidelines. Irish Road Safety Authority. Retrieved 21/12/16 from: http://www.rsa.ie/Documents/Licensed%20Drivers/Medical_Issues/Sl%C3%A1inte_agus_Tiom%C3%A1int_Medical_Fitness_to_Drive_Guidelines.pdf

NHTSA (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration) & AAMVA (American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators). (2009). Driver Fitness Medical Guidelines. Retrieved 04/01/17 from: https://www.ems.gov/pdf/811210.pdf.

CCMTA. (2013). Determining driving fitness in Canada: Part 1: A model for the administration of driving fitness programs and Part 2: CCMTA Medical Standards for Drivers. Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators. Retrieved 21/12/16 from: https://www.transportation.alberta.ca/content/docType45/Production/CCMTADriverMedicalStandardsAugust2013.pdf

Jerome L, Segal A, Habinski L. What we know about ADHD and driving risk: a literature review, meta-analysis and critique. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;15(3):105–25.

Bruce C, Unsworth CA, Tay R. A systematic review of the effectiveness of behavioral interventions for improving driving outcomes in novice drivers with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Occup Ther. 2014;77(7):348–57.

Gobbo MA, Louza MR. Influence of stimulant and non-stimulant drug treatment on driving performance in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(9):1425–43.

Classen S, Monahan M. Evidence-based review on interventions and determinants of driving performance in teens with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or autism spectrum disorder. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2013;14(2):188–93.

Barkley RA, Cox D. A review of driving risks and impairments associated with attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder and the effects of stimulant medication on driving performance. J Saf Res. 2007;38(1):113–28.

Tsuang MT, Boor M, Fleming JA. Psychiatric aspects of traffic accidents. Am J Psychiatr. 1985;142(5):538–46.

Menard I, Korner-Bitensky N. Fitness to drive in persons with psychiatric disorders and those using psychotropic medications. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2008;24(1):47–64.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA): the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Edlund, W., Gronseth, G., So, Y., & Franklin, G. (2004). Clinical Practice Guideline Process Manual. Retrieved 21/12/16 from: https://www.aan.com/uploadedFiles/Website_Library_Assets/Documents/2.Clinical_Guidelines/4.About_Guidelines/1.How_Guidelines_Are_Developed/2004%20AAN%20Process%20Manual.pdf

Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. (2009). Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine – Levels of Evidence. Retrieved 21/12/16 from: http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/

Brunnauer A, Buschert V, Segmiller F, Zwick S, Bufler J, Schmauss M, et al. Mobility behaviour and driving status of patients with mental disorders - an exploratory study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20(1):40–6.

De Las Cuevas C, Sanz EJ. Fitness to drive of psychiatric patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(5):384–90.

McNamara C, Buckley SE. The road to recovery: experiences of driving with bipolar disorder. Br J Occup Ther. 2015;78(6):356–63.

Niveau G, Kelley-Puskas M. Psychiatric disorders and fitness to drive. J Med Ethics. 2001;27(1):36–9.

Segmiller, F. M., Buschert, V., Laux, G., Nedopil, N., Palm, U., Furjanic, K., ... & Brunnauer, A. (2015). Driving skills in unmedicated first-and recurrent-episode schizophrenic patients. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 1–6.

Zingg C, Puelschen D, Soyka M. Neuropsychological assessment of driving ability and self-evaluation: a comparison between driving offenders and a control group. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;259(8):491–8.

Langan C. Psychiatric illness and driving: Irish psychiatrists' documentation practices. Ir J Psychol Med. 2009;26(1):16–9.

Menard I, Korner-Bitensky N, Dobbs B, Casacalenda N, Beck PR, Gelinas I, et al. Canadian psychiatrists' current attitudes, practices, and knowledge regarding fitness to drive in individuals with mental illness: a cross-Canada survey. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;51(13):836–46.

Menard I, Benoit M, Boule-Laghzali N, Hebert M-C, Parent-Taillon J, Perusse J, et al. Occupational therapists' perceptions of their role in the screening and assessment of the driving capacity of people with mental illnesses. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2012;28(1):36–50.

Rouleau S, Mazer B, Menard I, Maryse G. A survey on driving in clients with mental health disorders. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2010;26(1):85–95.

Vrkljan BH, Myers AM, Blanchard RA, Crizzle AM, Marshall S. Practices used by occupational therapists and others in driving assessment centers for determining fitness-to-drive: a case-based approach. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics. 2015;33(2):163–74. https://doi.org/10.3109/02703181.2015.1016647.

Crancer A Jr, Quiring DL. The mentally ill as motor vehicle operators. Am J Psychiatr. 1969;126(6):807–13.

Eelkema RC, Brosseau J, Koshnick R, McGee C. A statistical study on the relationship between mental illness and traffic accidents - a pilot study. American Journal of Public Health Nations Health. 1970;60(3):459–69.

Kastrup M, Dupont A, Bille M. Traffic accidents involving psychiatric patients. Description of the material and general results. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1977;55(5):355–68.

Kastrup M, Dupont A, Bille M, Lund H. Traffic accidents involving psychiatric patients: characteristics of accidents involving drivers who have been admitted to Danish psychiatric departments. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1978;58(1):30–9.

Brunnauer A, Laux G. Driving ability under sertindole. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2012;67(11):1776–81.

Hawley CA, Galbraith ND, De Souza VD. Medical education on fitness to drive: a survey of all UK medical schools. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:635–8.

O’Neill D, Crosby T, Shaw A, Haigh R, Hendra TJ. Fitness to drive and the older patient: aware ness among hospital physicians. Lancet. 1994;344:1366–7.

Yale SH, Hansotia P, Knapp D, Ehrfurth J. Neurological conditions: assessing medical fitness to drive. Clin Med Res. 2003;1(3):177–88.

Kahvedžic A, Mcfadden R, Cummins G, Carr D, O'Neill D. Impact of new guidelines and educational programme on awareness of medical fitness to drive among general practitioners in Ireland. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2015;16(6):593–8.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No grant support was received from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profile sectors.

Availability of data and materials

All studies included in the review are listed in Additional file 1. All data included in analysis is appended in Table 3: Summary of key findings and quality appraisal of the 15 included studies (16 papers), presented by sub-group. The review protocol is available from the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Two authors (CU and MS) independently completed data extraction. Two authors (CU and MS) independently screened titles and abstracts of all identified studies, excluded ineligible studies against the inclusion/exclusion criteria and assessed the quality of the articles. AB, PH and DO reviewed the findings and drafted the results and discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

Professor Carolyn Unsworth is Professor of Occupational Therapy at Central Queensland University, Australia, adjunct Professor at Jonkoping University Sweden, La Trobe University Australia, and Curtin University Australia.

Dr. Anne Baker is a Lecturer in Occupational Therapy at Australian Catholic University, Australia.

Man Hei So is a research assistant at Central Queensland University, Australia.

Professor Priscilla Harries is Chair of the Royal College of Occupational Therapists’ R&D Committee, UK, and Head of Department of Clinical Sciences at Brunel University London, England.

Professor Desmond O’Neill is the Director of the Centre for Ageing, Neuroscience and the Humanities, Dublin, Ireland.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable as this is a systematic review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable as this is a systematic review.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Citations details of studies included in Aim 1 of the study. (DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Unsworth, C.A., Baker, A.M., So, M.H. et al. A systematic review of evidence for fitness-to-drive among people with the mental health conditions of schizophrenia, stress/anxiety disorder, depression, personality disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder. BMC Psychiatry 17, 318 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1481-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1481-1