Abstract

Background

Recent studies analysing the trends in antipsychotic (AP) prescriptions for children and adolescents have raised concerns regarding the influence of socioeconomic status. Previous findings have also shown variable prescription rates for first-generation (FG) and second-generation (SG) APs.

Method

Our objectives were to assess the proportion of patients from low-income families receiving APs and the most commonly prescribed APs in France. We conducted a descriptive analysis of AP drugs dispensed during a 1-year period (July 1, 2013–June 30, 2014) in a northwestern region of France with 941,857 subjects less than 18 years old. All data were extracted from an exhaustive, individual and anonymous social security database. We obtained each subject’s socioeconomic status (by identifying their affiliation with a specific social security program) and also collected sociodemographic data, drug type, prescribing and dispensing dates and amount, and prescriber type (e.g., hospital physician, general practitioner, psychiatrist, paediatrician).

Results

There were two main novel findings. First, we found that the proportion of patients with AP prescriptions was nearly ten times higher in low-income families than in the general population: 35.9% of CMU-C patients compared to 3.7% in all of Pays de la Loire (X 2 = 7875.1, p < 0.001). Additionally, we found a higher rate of FGAP than SGAP prescriptions (65% vs. 57%).

Conclusions

Our study suggests two types of AP misuse that could provide interesting targets for public healthcare interventions.

First, our results strongly suggest an over-representation of patients from low-income families. Low-income families primarily resided in areas with low physician density and appeared to receive drugs to treat their conditions more frequently than other individuals. This increased prescription rate is a public health issue, potentially requiring political action. Second, the use of FGAPs did not adhere to the latest recommendations for drug use in this population, and this discrepancy should be addressed with informational campaigns targeted to medical practitioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Antipsychotic (AP) drugs are recommended for the treatment for schizophrenia [1] and bipolar disorders [2] in children and adolescents. These drugs are effective in managing the core symptoms of these two diseases [1, 2]. APs are also partly effective and thus prescribed to manage attention deficit hyperactivity disorders, disruptive behaviour disorders, Tourette’s syndrome, post-traumatic stress disorder, anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum disorders [3, 4]. The recent literature regarding the prescription of APs raises two main issues:

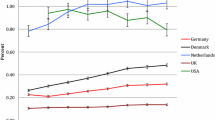

The first pertains to the use of first- and second-generation APs. Considering the data on their efficacy and side effects, the literature recommends a first-line prescription of a second-generation AP (SGAP) and then switching to another SGAP if necessary before considering a first-generation AP (FGAP) [1]. The choice of prescription should balance the benefits and risks of the drug, particularly in younger populations, who experience more side effects than adults [5, 6]. A recent study showed that AP treatment is associated with increased body weight and cardiometabolic side effects as well as different side effect patterns [5]. The use of SGAPs is now recommended, and longitudinal studies have shown an increase in AP prescriptions in the last two decades with a switch from FGAPs to SGAPs [7–9]. However, some European studies, including those in France, have found that FGAPs are still much prescribed in this population, whereas in the U.S., the rate of FGAP prescriptions among youth is now very low [4, 10].

The second issue is related to the patients’ socioeconomic status (SES). Very few studies have explored the influence of socioeconomic/residential status on AP prescription rates. Existing research has focused on rural vs. urban inhabitants [11, 12] and has found no correlations between these parameters and AP prescriptions. Two recent studies on this topic yielded conflicting results. One study reported that AP prescriptions were more common among people from low-income areas in the UK [13], whereas the second study failed to find an association between AP consumption by youth and the rate of welfare benefits [14]. These inconsistent findings may have occurred because the authors correlated the overall rate of AP prescriptions with welfare benefits of geographic locations rather than individual welfare data. The effect of SES might be more related to individual factors than to the geographic location.

To study these two issues, we conducted a descriptive analysis of drugs dispensed during a 1-year period (July 1, 2013–June 30, 2014) in an exhaustive study of a northwestern region of France with 3,658,000 inhabitants, including 941,857 subjects younger than 18 years old whose socioeconomic conditions were known.

Methods

Data source and population sample

We conducted an observational study of a retrospective cohort using a healthcare database that included information on subjects living in one area (Pays de la Loire) with five different counties (Loire Atlantique, Maine et Loire, Mayenne, Sarthe, and Vendée).

The data were extracted from one database (datamart de Consommation Inter Regimes, DCIR) that was part of the French healthcare insurance database (Système National d’Information Inter Régimes de l’Assurance Maladie, SNIIR-AM), which contains all of the information from the main insurance schemes in France; the SNIIR-AM covers salaried workers, farm workers, non-salaried workers (i.e., craftsmen and tradesmen), and a few other special groups (i.e., teachers, policemen, and armed forces). Affiliation with one of these schemes is mandatory (i.e., persons cannot be outside of the database). The DCIR database is an exhaustive, individual and anonymous healthcare database that includes all information on refunded healthcare claims. Individuals cannot purchase any of the included drugs without a pharmacist’s report of this prescription being documented in the DCIR. Therefore, it is the main point of access for information on drug consumption by a large group of individuals. As with all subjects, individuals younger than 18 years have their own anonymous health service code, which is a lifetime code that uniquely identifies each resident.

Our population sample was composed of all children and adolescents younger than 18 years old at the end of the study period (July 1, 2013, to June 30, 2014) who were living in the Pays de la Loire area (northwestern France, 3.658 million inhabitants in 2013 [15]). All characteristics of the youth who received at least one dispensation of psychotropic drugs were obtained (n = 17.198).

Psychotropic drug selection process in the database

Drugs were identified using the International Non-proprietary Name (INN) and categorized using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system [16], which is commonly applied in epidemiologic studies. We selected APs, which are a subcategory of N05, the N05A group. We also added valproic acid (N03AG01) and valpromide (N03AG02). The total list of drugs included was as follows: Chlorpromazine, Levomepromazine, Cyamemazine, Valproic acid, Valpromide, Periciazine, Pipamperone, Haloperidol, Flupentixol, Zuclopenthixol, Pimozide, Loxapine, Clozapine, Olanzapine, Quetiapine, Sulpiride, Tiapride, Amisulpride, Risperidone, Aripiprazole, and Paliperidone.

Valproic acid and valpromide are commonly used for their AP effects by prescribers in general practice in France (even if they are off-label), and we chose to include them after a consensus meeting with all the authors of this article (i.e., OB, CC, PH, CV, PJ).

Study measures

We collected information on participants’ sociodemographic data (gender, county, affiliated healthcare insurance scheme, age, and CMU-C status). Couverture Maladie Universelle Complémentaire (CMU-C) is a supplemental universal public insurance coverage scheme for low-income persons. The criteria for accessing the CMU-C include an income less than 721 euros/month for a single individual, adding 250 euros for each member of the family. Affiliation with CMU-C is considered a poverty threshold in France. Therefore, CMU-C status defines the group of people under the poverty threshold in France.

We created 5 age categories: 0–4, 5–9, 10–14 and 15–17 years old.

Regarding medications, we collected the type of drug dispensed (INN and ATC code (5th level)), the date of dispensation, the date of prescription, the number of dispensations, and the prescriber type (e.g., hospital physician, general practitioner, psychiatrist, paediatrician).

Our database granted access to all drugs dispensed and reimbursed in a pharmacy (and thus all prescriptions). We were able to determine how many different dispensations each patient had received during the study period. In France, drugs are provided to patients in complete blister cards (with a pre-defined number of slots), not by pills. Patients are usually given 1 month of treatment per dispensation (with the number of complete blister cards calculated accordingly). Therefore, patients typically receive extra pills, which may represent more than a 1-month supply. We determined the treatment duration for each subject by accessing the number of different months of dispensation in the follow-up for each drug. The month of dispensation was obtained to determine whether treatment was chronic (continuous variable), and we considered subjects receiving at least 6 months of dispensations as chronic users, which was consistent with the methodology of a previous study using this database [14].

Finally, it was difficult to determine the type of hospital practitioner prescribing APs. All prescriptions from physicians working in a hospital are dispensed with the unique identification number of the hospital. Currently, the only way to access information on the type of hospital practitioner is to access the actual prescription, which would have provided the name and medical speciality of the physician; however, this approach was not possible in our study for ethical reasons (lack of anonymity).

We also searched for national data regarding the general population. We focused on the number of inhabitants [15], proportion of CMU-C patients [17] and medical density in the study region [18].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise software version 4.3, and the detailed data were extracted and analysed by individuals who manage the healthcare insurance database according to the national commission for liberty and informatics (CNIL) laws.

A descriptive analysis was performed for sociodemographic and drug prescription data. We also calculated the proportion of AP prescriptions in comparison with general population data.

A proportions test based on chi2 was performed to compare the prevalence of CMU-C patients in our sample with that of the general population.

Results

Prescription overview

Among all patients in the Pays de la Loire region, 0.33% (2,897 children and adolescents under 18 years old) had an AP prescribed and dispensed during the observation period (see Table 1). Half of these prescriptions were for patients aged 13 years or younger (48%). Prescriptions increased with age and were higher in boys than in girls (0.47 in boys and 0.18 in girls).

Our results also showed that the overall AP prescription rate differed by county. Two counties were above the average prescription rate (0.33%): Mayenne (0.72%) and Maine et Loire (0.40%). Some rates, such as AP prescriptions for boys 5 to 9 years old in Mayenne vs. all areas (0.98 compared to 0.30), were of particular importance. The results in Mayenne were higher than the average for all sex and age subgroups; for example: 0.52 vs. 0.24% for girls aged 10–14 years and 1.75 vs 0.74% for boys aged 10–14 years. We present AP prescription rates by county with medical density in Table 2 (using data from the Conseil National de l’Ordre des Medecins) [18].

CMU-C-affiliated population

The proportion of individuals affiliated with CMU-C in our study was approximately 1/3 of our population (35.9%). When compared to the rates in the general population in Pays de la Loire, Chi2 comparison tests showed a higher proportion of CMU-C patients in our sample (X 2 = 7875.1, p < 0.001). The results were similar in all counties (see Table 3). CMU-C affiliation was higher in families with children over 5 years: 22.7% for ages 0–4, 36.3% for ages 5–9, 35.5% for ages 10–14 and 36.7% for ages 15–17 years.

AP-specific medication data

Regarding single prescriptions, FGAPs were prescribed more frequently than SGAPs (65% vs. 57%). The ratio of FGAPs to SGAPs decreased with age, at 86% vs. 32% for subjects 0–4 years old and 63% vs. 61% for subjects 15–17 years old. In our study, 23% of subjects received both FGAPs and SGAPs. The overall data for all prescriptions (single and combination) are presented in Table 4.

The most commonly prescribed APs were cyamemazine and risperidone, totalling 1,379 and 1,303 prescriptions, respectively. Aripiprazole was the third-most prescribed AP, with only 207 prescriptions.

Regarding the duration of cyamemazine treatment, 33% of children/adolescents (463 of 1,379) had only a 1-month dispensation, and 27% (366 of 1 379) had 6 separate months with one or more dispensations per year. For risperidone, 18% of children/adolescents (230 of 1,303) had only one month of dispensed drugs, and 41% (532 of 1,303) had 6 separate months with one or more dispensations per year.

Regarding the type of prescribers, hospital physicians comprised 73.2% of the total. For 46.3% of the patients, these doctors were their only prescriber. General practitioners prescribed 11.4% of the patients’ prescriptions during the study period (results are in Table 5).

Discussion

This study presented two main novel results. First, we found that the proportion of patients with APs was almost ten times higher in low-income families than in the general population: 35.9% of low SES patients compared to 3.7% in all of Pays de la Loire (X 2 = 7875.1, p < 0.001). In addition, we found a higher rate of FGAP than SGAP prescriptions (65% vs. 57%).

In general, our sample is comparable to those of other recent French studies, as our overall AP prescription rate was 0.33% (0.47 in boys and 0.18 in girls) for patients under 18 years old. Three major studies on the use of AP medications have been conducted using the French healthcare insurance database. In 2004, a study was conducted in two different regions, showing that 0.3% of patients used APs and that the rates increased with age [19, 20]. Using a different methodology and a random sample (1%) from the 2010 national database, another study reported an overall AP prescription rate of approximately 0.27–0.33% (0.35–0.45% for boys) [21]. A recent study examined a random representative sample of the French population (1%) extracted from the healthcare insurance database from 2006 to 2013 [14] and found an overall AP prescription rate of 0.49% for patients under 25 years old, 0.47% for patients between 11 and 15 years old, and 0.26% for patients between 6 and 10 years old.

These results are also consistent with recent studies in Europe. For example, a study in Germany used a similar method involving an exhaustive data source from a large area and found that the rate of AP prescriptions in 2012 was 0.33% and increased with age [13, 22]. Compared to older studies and those with different methodologies (smaller, non-exhaustive samples or random partial extractions of a large population), our results are within the mean range of data from Western countries, which show prevalences of APs ranging from 0.08% in Italy [23] to 0.76% in the U.S. [24]. Our rates in France are lower than those in the U.S., with the most recent French data reporting AP use in 2006 and 2010 by 0.14% and 0.11% of younger children, 0.85% and 0.80% of older children, 1.10% and 1.19% of adolescents, and 0.69% and 0.84% of young adults [21].

Socioeconomic status

The results regarding SES are important and similar in all counties (see Table 3). To our knowledge, this type of data has not been presented in previous studies. Although these results differ from comparable French [14] and Canadian [12] studies, previous authors compared the global rate of low SES patients in an area to the AP rate, whereas our study included each parent’s CMU-C affiliation. Our approach provides a different perspective and suggests, by incorporating individual status, that being from a low-income family instead of simply living in a low-income area may be associated with increased prescription of APs.

In the same vein, we also found that the geographical distribution of AP users was not homogeneous and was greater in counties with the lowest medical density compared to those with a higher medical density (see Table 2). The ratio of medical facilities in the entire region was 272.7/100,000 inhabitants, which is slightly lower than the national density of 299.7/100,000 [18]. Moreover, the county with the lowest rate of AP prescriptions was Loire Atlantique, which also has the highest density of medical facilities. In contrast, the highest rate (0.72) was found in Mayenne, where the medical density is the lowest. These data suggest that individuals with greater medical access receive fewer AP prescriptions (see Table 2).

We found conflicting evidence in the literature regarding the impact of residence on AP prescriptions. A study from Taiwan found that AP prescriptions for patients aged 18 years or under were more frequent in suburban areas than in urban and rural areas [11], although this relationship was not found in a Canadian study [12]. However, Verdoux and colleagues found an increase in the level of AP prescriptions in areas with a low density of health facilities for children under 10 years old and in areas with low socioeconomic resources (global CMU-C affiliation rate in the area) for adolescents aged 16–20 years [14]. These conflicting results can be explained, again, by their use of data from large groups rather than from individually oriented data.

However, we could not determine a correlation between the density of medical facilities and access to health resources because of imprecisions in our data. Access to health care facilities depends on the exact part of the county where the patient resides (e.g., a family living in southern Mayenne may have better access to the University Hospital of Angers in Maine et Loire than some people in the extreme south of the Angers area). Another limitation of our study is that our data could not determine the purpose of the prescription or the patients’ diagnoses. For obvious privacy reasons, anonymous data prohibit access to these data in French insurance databases. Accordingly, we could not link AP prescriptions to specific diagnoses.

The higher level of AP prescriptions among children and adolescents from low-income families can be explained by two hypotheses:

-

1.

Patients from low SES families are known to exhibit more psychiatric disorders, especially those associated with behavioural disturbances [25, 26]. This correlation is stronger for anxiety and mood disorders (which may be associated with behavioural disturbances in youth) and ADHD than for diseases such as autism, schizophrenia and Tourette’s syndrome [25, 26], which are core indications for AP prescription. Moreover, a higher incidence of behavioural problems has been found among preschool children from low SES families [27] and adolescents living in poverty [28]. Unfortunately, we were not able to verify this hypothesis, as we could not determine diagnoses in our sample.

-

2.

The second hypothesis is related to the specific situations regarding child and adolescent psychiatry in France. A large percentage of child and adolescent psychiatrists in France do not commonly prescribe psychotropic medications, particularly APs. This practice is associated with the strong psychoanalytic culture in France along with a lack of current scientific knowledge about medications. Most of our colleagues consider themselves psychotherapists. Therefore, a psychiatrist may be more likely to prescribe medications for behavioural reasons than for developmental disorders (e.g., autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia [29], Tourette’s). Additionally, there are few hospitalizations that occur for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders due to the limited number of beds in France for emergencies or short periods (13.5/100,000 inhabitants), especially in Pays de la Loire (7/100 000 in Loire Atlantique, 9 in Maine et Loire and 12 in Sarthe, with other counties having only long-term hospitalizations, which are more similar to boarding school) [30]. There is also a lack of non-medical psychiatric healthcare professionals such as clinical psychologists, as in contrast to psychiatrists, psychologists’ interviews are not reimbursed by social security [15].

These hypotheses may be synergistic. APs are frequently used to treat behavioural issues and may provide a quick solution to complex situations that would benefit from individual and family evaluation and support. When patients from low SES families exhibit more behavioural disorders, they encounter psychiatrists with few therapeutic options other than medications. Patients from higher SES families may be more likely to seek psychologists in private practice or re-educators (whose visits are not free).

Further studies that evaluate the specific level of care (medical and social) and the exact purpose for AP prescriptions are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

FGAPs vs. SGAPs

The rates of FGAP compared to those of SGAPs were particularly high among younger patients: 86% vs. 32%, respectively, for ages 0–4 years and 69% vs. 44%, respectively, for ages 5–9 years. Remarkably, the rates remained high in children 10 to 13 years old (39.2% FGAP vs. 34.4% SGAP) and adolescents from 15 to 17 years old (36.1% FGAP vs. 34.1% SGAP). Indeed, recent AMMs (Market Release Authorizations) for SGAPs have made them available to 13- to 15-year-old patients instead of only 18-year-old patients (for aripiprazole, olanzapine and risperidone). Moreover, in 2007, an AMM was obtained for the use of risperidone in 5-year-olds for behavioural disorders involving intellectual deficiency. Therefore, SGAPs could have been prescribed more extensively.

Our results indicate higher rates of FGAP than those reported in the most recent comparable studies in France [14, 31] for all ages, with rates of FGAPs vs. SGAPs for infants, children and adolescents of 86.3% vs. 53.6%, 68.9% vs. 41.5% and 83.9% vs. 58.8%, respectively [14]. However, these previous studies involved a representative national sample that did not reflect regional disparities (see explanation for Pays de la Loire above).

This high level of FGAP prescription may be harmful because the side effect profile of APs differs drastically, especially in the paediatric population [6, 32]. In other countries, longitudinal studies have shown an increase in AP prescriptions in the last two decades as well as a switch from FGAPs to SGAPs [7–9].

The high use of cyamemazine, which was the most commonly prescribed AP in our study, is likely related to French habits. In France, cyamemazine is mainly used as a sedative and anxiolytic drug, despite its poor tolerance due to metabolic syndrome as well as its limited AP effects [33]. Cyamemazine was also originally developed by a French laboratory and was marketed heavily in the 1990s. However, cyamemazine has a low affinity for dopaminergic receptors and therefore poor AP activity. The sedative effects of cyamemazine are mediated through its 5HT2A activity [34]. The main scientific literature regarding cyamemazine has investigated its efficacy in treating benzodiazepine withdrawal, particularly for alcoholic patients (for a review, see [35]). The very high level of cyamemazine use is likely related to a lack of knowledge of the efficacy and side effects as well as to prescribers’ habits. The lack of knowledge about new SGAPs and their AMMs for younger patients may also be a reason for the low level of SGAP prescription, particularly during adolescence. Our results are comparable with those of previous studies showing a high rate of cyamemazine use in France [14].

Conclusion

Our epidemiological study in an exhaustive population demonstrated that the consumption of APs is concerning, occurring in 33 children and adolescents out of 10,000. This overall rate is admissible, but the qualitative analysis suggests a few concerning findings that should be addressed.

There was a misuse of APs, with an excessive number of FGAP prescriptions, especially for cyamemazine. This practice appears to be related to a lack of knowledge regarding the efficacy and side effects of this drug. The FGAP/SGAP ratio in northwest France was higher than the national mean [14] and was not compliant with the latest recommendations for drug use in this population. This discrepancy should be addressed through an information campaign directed towards medical practitioners and in the teaching of medical students. As our work was conducted with the French National Health Insurance organization, a full partnership to undertake this type of campaign is already in place.

Despite the lack of information regarding the reasons for prescription, our results strongly suggest an over-representation of patients from low SES families in our sample of youth receiving APs. These patients were mainly living in areas with a low physician density and received drugs to treat their conditions more often than other individuals. Therefore, it is important to communicate these findings to medical practitioners, and political action to address these discrepancies may be necessary.

Abbreviations

- ADHD:

-

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- AP:

-

Antipsychotic

- ATC:

-

Anatomical therapeutic chemical

- BP:

-

Bipolar disorder

- CNIL:

-

Commission Natioanale Informatique et Liberté = national commission for liberty and informatics

- DCIR:

-

Datamart de Consommation Inter Regimes

- EMA:

-

European medicine agency

- ESCAPAD:

-

Enquete sur la Santé et les Consommations lors de l’appel de la Preparation à la Defense Nationale = survey on health and consummation during army conscription mandatory day

- FDA:

-

Food and drug administration

- FGAP:

-

First generation antipsychotic

- INN:

-

International non-proprietary name

- SGAP:

-

Second generation antipsychotic

References

McClellan J, Stock S, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:976–90.

Goldstein BI, Sassi R, Diler RS. Pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;21:911–39.

Carton L, Cottencin O, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Geoffroy PA, Favre J, Simon N, et al. Off-Label prescribing of antipsychotics in adults, children and elderly individuals: A systematic review of recent prescription trends. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21:3280–97.

Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Treatment of young people with antipsychotic medications in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:867–74.

Arango C, Giráldez M, Merchán-Naranjo J, Baeza I, Castro-Fornieles J, Alda JA, et al. Second-generation antipsychotic use in children and adolescents: a 6-month prospective cohort study in drug-naive patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:1179–90,1190.e1.

Cohen D, Bonnot O, Bodeau N, Consoli A, Laurent C. Adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a Bayesian meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32:309–16.

Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, Moloney RM, Stafford RS. Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995–2008. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:177–84.

Olfson M. Epidemiologic and clinical perspectives on antipsychotic treatment of children and adolescents. Can J Psychiatry Rev Canadienne Psychiatrie. 2012;57:715–6.

Verdoux H, Tournier M, Bégaud B. Antipsychotic prescribing trends: a review of pharmaco-epidemiological studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121:4–10.

Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu SM, Wang S, Correll CU. National trends in the office-based treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with antipsychotics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:1247–56.

Hsu YC, Chien IC, Tan HK, Lin CH, Cheng SW, Chou YJ, et al. Trends, correlates, and disease patterns of antipsychotic use among children and adolescents in Taiwan. Soc Psych Psych Epid. 2013;48:1889–96.

Alessi-Severini S, Biscontri RG, Collins DM, Sareen J, Enns MW. Ten years of antipsychotic prescribing to children: a Canadian population-based study. Can J Psychiat. 2012;57:52–8.

Marston L, Nazareth I, Petersen I, Walters K, Osborn DP. Prescribing of antipsychotics in UK primary care: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2014;4, e006135.

Verdoux H, Pambrun E, Cortaredona S, Tournier M, Verger P. Antipsychotic prescribing in youths: a French community-based study from 2006 to 2013. Eur Child Adoles Psy. 2015;24:1181–91.

INSEE, Répartition des médecins et chirurgiens. 2016. https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/2012677. Accessed 13 Feb 2017.

ATC Classification 2015. http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. Accessed 13 Feb 2017.

IDRES, LEs bénéficiaires de la CMU-C. 2015. http://www.irdes.fr/EspaceEnseignement/ChiffresGraphiques/Cadrage/CMU/CMUC.htm. Accessed 13 Feb 2017.

CNOM, Démographie médicale. 2015. http://www.conseilnational.medecin.fr/sites/default/files/pays_de_la_loire_2013_0.pdf. Accessed 13 Feb 2017.

Acquaviva E, Legleye S, Auleley GR, Deligne J, Carel D, Falissard BB. Psychotropic medication in the French child and adolescent population: prevalence estimation from health insurance data and national self-report survey data. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:72.

Observatoire Français des Drogues et Toxicomanies. Estimation 2014 des consommations de produits psychoactifs à 17 ans. 2016. http://www.ofdt.fr/BDD/publications/docs/eisxfbv4b.pdf. Accessed 13 Feb 2017.

Kovess V, Choppin S, Gao F, Pivette M, Husky M, Leray E. Psychotropic medication use in French children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25:168–75.

Bachmann CJ, Lempp T, Glaeske G, Hoffmann F. Antipsychotic prescription in children and adolescents: an analysis of data from a German statutory health insurance company from 2005 to 2012. Deutsches Arzteblatt International. 2014;111:25–34.

Clavenna A, Andretta M, Pilati P, Dusi M, Gangemi M, Gattoni MB, et al. Antidepressant and antipsychotic use in an Italian pediatric population. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:40.

Zito JM, Safer DJ, de Jong-van den Berg LT, Janhsen K, Fegert JM, Gardner JF, et al. A three-country comparison of psychotropic medication prevalence in youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2:26.

Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, The Christchurch Health and Development Study. The Christchurch Health and Development Study: Review of findings on child and adolescent mental health. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2001;35:287–96.

Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, Kessler RC. Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dial Clin Neurosci. 2009;11:7–20.

Qi CH, et al. The performance of low-income, African American children on the Preschool Language Scale-3. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2003;46(3):576–90.

Dashiff C, DiMicco W, Myers B, Sheppard K. Poverty and adolescent mental health. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;22:23–32.

Rapoport JL, Giedd JN, Gogtay N. Neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2012. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:1228–38.

Score Sante. Eco-Données Santé. 2016. http://www.scoresante.org/score2008/sindicateurs.html. Accessed 13 Feb 2017.

Patten SB, Waheed W, Bresee L. A review of pharmacoepidemiologic studies of antipsychotic use in children and adolescents. Can J Psychiat. 2012;57:717–21.

Arango C, Giráldez M, Merchán-Naranjo J, Baeza I, Castro-Fornieles J, Alda JA, et al. Second-generation antipsychotic use in children and adolescents: a 6-month prospective cohort study in drug-naïve patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:1179–90,1190.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.08.009.

Baylé FJ, Blanc O, De Chazeron I, Lesturgeon J, Lançon C, Caci H, et al. Pharmacological management of anxiety in patients suffering from schizophrenia. Encéphale. 2011;37 Suppl 1:S83–9.

Bourin M, Dailly E, Hascöet M. Preclinical and clinical pharmacology of cyamemazine: anxiolytic effects and prevention of alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. CNS Drug Rev. 2004;10:219–29.

Benyamina A, Naassila M, Bourin M. Potential role of cortical 5-HT (2A) receptors in the anxiolytic action of cyamemazine in benzodiazepine withdrawal. Psychiatry Res. 2012;198:307–12.

Acknowledgements

None - all work was performed by the authors.

Funding

No funding was used and was not necessary for this survey.

Availability of data and materials

We do not wish to share the data as they are exclusive property of the French National Health Insurance Information System (SNIIRAM) and the statistics were generated directly in the datamart base (not connected to an outside network and only readable in FHIS main offices).

Authors’ contributions

MD, OB, CV, PH, AS, AC, JP and EM were involved in the study conception and design and the analysis and interpretation of data. OB, MD, PH drafted the article; CV, AC, AS, JP and EM critically revised it for important intellectual content; tables were constructed by MD, OB and CV. Data were extracted by MD, EM, AC and JP (CPAM team). All authors provided final approval of the version to be published.

Authors’ information

Mélanie Dufresne: melanie.dufresne@ersm-paysloire.cnamts.fr, Emmanuelle Michaud: emmanuelle.michaud@ersm-paysloire.cnamts.fr, Jacques Pivette: jacques.pivette@ersm-paysloire.cnamts.fr, Anicet Chaslerie: anicet.chaslerie@ersm-paysloire.cnamts.fr are MD and working at Medical Department, French National Health Insurance (DRSM), Nantes, France.

Paula Herrera: polatija@yahoo.com is MD, PhD and working at Grupo de Investigación en Neurociencias NeURos, Universidad del Rosario, Bogota, Colombia.

Anne Sauvaget: anne.sauvaget@chu-nantes.fr, is MD and working in Department of Psychiatry, University Hospital of Nantes, France.

Caroline Vigneau: caroline.vigneau@chu-nantes.fr is MD, PhD and working at Department of Pharmacology, University Hospital of Nantes, France.

Olivier Bonnot is MD, PhD and is head of Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at CHU de Nantes.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. Data are anonymized irreversibly by the FOIN system (Fonction d’Occultation des Identifiants Nominatifs) of the French National Health Insurance Information System (SNIIRAM).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All data were obtained from the French National Health Insurance Information System (SNIIRAM). The access to data and the data analysis were granted by decree for a period of only 3 years plus the current year and authorization was obtained from the French Data Protection Authority (Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés, CNIL). Arrêté du 19 juillet 2013 relatif à la mise en œuvre du Système national d’information interrégimes de l’assurance maladie NOR: AFSS1318985A Version consolidée au 07 avril 2016 https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000027830713. Approval for data use was provided by the owner of the data: CPAM (France Healthcare Insurance).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bonnot, O., Dufresne, M., Herrera, P. et al. Influence of socioeconomic status on antipsychotic prescriptions among youth in France. BMC Psychiatry 17, 82 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1232-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1232-3