Abstract

Background

Although previous studies found that aberrations in gray matter volume (GMV) and global functional connectivity density (gFCD) are important characteristics of schizophrenia, to the best of our knowledge no study to date has investigated the associations between the spatial distribution patterns of GMV and gFCD alterations. We investigated pattern changes in gFCD and GMV among patients with schizophrenia and their associated spatial distributions.

Methods

Ninety-five patients with schizophrenia and 93 matched healthy controls underwent structural and resting-state functional MRI scanning to assess gFCD and GMV.

Results

We found that gFCD increased in the subcortical regions (caudate, pallidum, putamen, and thalami) and limbic system (left hippocampus and parahippocampus), and decreased in the posterior parieto-occipito-temporal cortices (postcentral gyri, occipital cortex, temporo-occipital conjunction, and inferior parietal lobule), in patients with schizophrenia. By contrast, we found decreased GMV in brain regions including the frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, cingulate cortices, and the insular, striatum, thalamus in these patients. Increased gFCD primarily occurred in subcortical regions including the basal ganglia and some regions of the limbic system. Decreased gFCD appeared primarily in the cortical regions. There were no statistically significant correlations between changes in gFCD and GMV, and their spatial distribution patterns, in different regions.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that gFCD and GMV are both perturbed in multiple brain regions in schizophrenia. gFCD and GMV consistently decreased in the cortical regions, with the exception of the Supplementary Motor Area (SMA). However, in the sub-cortical regions, the alterations of gFCD and GMV showed the opposite pattern, with increased gFCD and decreased GMV simultaneously observed in these regions. Overall, our findings suggest that structural and functional alterations appear to contribute independently to the neurobiology of schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the past few decades, numerous MRI studies have reported that schizophrenia is associated with widespread brain structural and functional alterations [1–14]. Previous studies have consistently confirmed that patients with schizophrenia have a diffused gray matter volume (GMV) decreases and that this is predominantly located in various cortical and subcortical brain regions. The overwhelming majority of studies have demonstrated that the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, cingulate cortex, hippocampus, thalami, and basal ganglia are key regions of GMV decrease in schizophrenia [1–8].

Echoing the alterations in brain structure in schizophrenia, considerable fMRI evidence suggests that functional alterations characterized by hyper-functional activity in sub-cortical regions (mainly in the basal ganglia and some regions of limbic system) with coexistent hypo- or hyper-functional activity in cortical regions occur in schizophrenia. The frontal, temporal and parietal lobes, cingulate gyrus, occipital gyrus, hippocampus, and thalami are key regions of functional alteration in schizophrenia [9–20].

According to previous studies, whole-brain measurement (VBM) is an unbiased and fully automated method used to investigate GMV alterations, which can be used as structural biomarkers for clinical and research applications in psychiatric disorders [21, 22]. Functional connectivity density mapping (FCDM) is a voxel-wise data-driven method that measures the number of functional connections between a given voxel and other voxels in the whole brain, producing a measure of global functional connectivity density (gFCD) [23–26]. gFCD has been developed to measure the number of resting-state functional connections of a given voxel with all other voxels in the entire brain and reflects a one-to-many relationship. While traditional functional connectivity mainly measures the connectivity (FC) strength between two voxels or regions or networks, which reflects a one-to-one relationship [23–27, 28]. Compared to traditional FC, gFCD can reflect the functional activity aberrant from another perspectives, a recent study have shown that gFCD is also a biomarker for psychiatric disorders [26]. Although previous studies found that aberrations in GMV and gFCD are important characteristics of schizophrenia, to the best of our knowledge no study to date has investigated the associations between the spatial distribution patterns of GMV and gFCD alterations.

Therefore, in the present study we aimed to investigate the alterations in GMV and gFCD, and their spatial distribution patterns in patients with schizophrenia, using VBM and FCDM. Several previous studies [17, 29, 30] reported that anatomical and functional brain aberrant are significantly dissociated with schizophrenia, anatomical aberrant has been most robust within thalamo-cortical regions, while functional aberrant has been most pronounced in fronto-parietal and default-mode networks regions. More importantly, the spatial and temporal distributions of anatomical and functional alterations are uncorrelated and the aberrant patterns are also inconsistent or even contradictory, demonstrate a “distinct patterns” [17]. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that gFCD and GMV would be altered in patients with schizophrenia compared with matched healthy controls. We also hypothesized that gFCD and GMV would both be affected in particular brain regions but that their spatial distributions and aberrant patterns (increased or decreased) are also unrelated, or even more complex [31–33].

Methods

Subjects

A total of 200 right-handed subjects participated in the study, including 98 patients with schizophrenia and 102 healthy controls. The patients were recruited from Tianjin Aning Hospital and Tianjn Anding Hospital and the healthy controls were recruited from the hospital staff or community residents. Patient diagnoses and illness duration were determined by the consensus of two senior psychiatrists using the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorder (SCID). All healthy controls were screened using the non-patient edition of the SCID to confirm a lifetime absence of psychiatric illnesses. Healthy controls were interviewed to exclude individuals with a known history of psychiatric illness in first-degree relatives. Exclusion criteria for all subjects were a history of head trauma with consciousness disturbances lasting more than 5 min, a history of substance abuse, pregnancy, or any physical illness, such as cardiovascular disease and neurological disorders, as diagnosed by interview or a review of their medical records. A professional radiologist assessed the MRIs slice-by-slice, and three patients and nine healthy controls were excluded owing to poor image quality. Consequently, the results for 95 patients with schizophrenia and 93 controls were analyzed (Fig. 1). The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) was used to assess the severity of patients’ psychotic symptoms. The Medical Research Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University General Hospital approved this study. Written informed consent was gained from each participant following a complete description of the study.

MRI data acquisition

MRI was performed using a 3.0-Tesla MR system (Discovery MR750, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Tight, but comfortable, foam padding was used to minimize head motion, and earplugs were used to reduce scanner noise. Sagittal 3D T1-weighted images were acquired using a brain volume sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 8.2 ms; echo time (TE) = 3.2 ms; inversion time (TI) = 450 ms; flip angle (FA) = 12°; field of view (FOV) = 256 mm × 256 mm; matrix = 256 × 256; slice thickness = 1 mm, no gap; and 188 sagittal slices). Resting-state fMRI data were acquired using a gradient-echo single-short Echo planar imaging sequence with the following parameters: TR/TE = 2000/45 ms; FOV = 220 mm × 220 mm; matrix = 64 × 64; FA = 90°; slice thickness = 4 mm; gap = 0.5 mm; 32 interleaved transverse slices; and 180 volumes. All subjects were requested to keep their eyes closed, relax, move as little as possible, think of nothing in particular, and not fall asleep during the scanning period.

fMRI data preprocessing

Resting-state fMRI data were preprocessed using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM8; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). The first 10 volumes for each subject were discarded to allow the signal to reach equilibrium and the participants to adapt to the scanning noise. The remaining volumes were corrected for the acquisition time delay between slices. Realignment was then performed to correct for motion between time points. All subjects’ fMRI data were within defined motion thresholds (i.e., translational or rotational motion parameters less than 2 mm or 2°). We also calculated frame-wise displacement, which indexes volume-to-volume changes in head position. Several nuisance covariates (six motion parameters, their first time derivations, and average BOLD signals of the ventricular and white matter) were regressed from the data. Recent study have reported that the signal spike caused by head motion significantly contaminates the final resting-state fMRI results even after regressing out the six motion parameters [34]. Therefore, we further regressed out spike volumes when the frame-wise displacement of the specific volume exceeded 0.5. The datasets were then band-pass filtered in a frequency range of 0.01 to 0.08 Hz [35]. In the normalization step, individual structural images were linearly co-registered with the mean functional image, and then linearly co-registered to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space. Finally, each filtered functional volume was spatially normalized to the MNI space using the co-registration parameters and were resampled into a 3-mm cubic voxel.

GMV calculation

The GMV of each voxel was calculated using SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm8/). Structural MR images were segmented into gray matter (GM), white matter and cerebrospinal fluid using the standard unified segmentation model. After an initial affine registration of the GM concentration map into the MNI space, GM concentration images were nonlinearly warped using the diffeomorphic anatomical registration through exponentiated lie algebra technique, and the results resampled to a voxel size of 3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm. The GMV of each voxel was obtained by multiplying the GM concentration map by the non-linear determinants derived from the spatial normalization step. Finally, the GMV images were smoothed using a Gaussian kernel of 6 mm × 6 mm × 6 mm full-width at half maximum. After spatial preprocessing, the smoothed GMV maps were used for statistical analyses.

FCD calculation

The FCD of each voxel was calculated using an in-house Linux script according to the method described by Tomasi and Volkow [23–26]. Pearson’s linear correlation evaluated the strength of the functional connectivity between voxels [36, 37]. According to the most of the previous studies, voxel pairs with a correlation coefficient of R > 0.6 were considered significantly connected, thereafter, in current study, we also adopted R > 0.6 as the cut-off point. [23–26, 38–40], FCD calculations were restricted to the cerebral gray matter mask regions. The gFCD at a given voxel, x0, was computed as the global number of functional connections, k(x0), between x0 and all other voxels. This calculation was repeated for all x0 voxels in the brain. The FCD maps were spatially smoothed using a 6 mm × 6 mm × 6 mm Gaussian kernel to minimize differences in the functional brain anatomy across subjects.

Statistical analysis

Group differences in GMV and gFCD were compared in a voxel-wise manner using a two-sample t-test with age and sex as nuisance variables. Multiple comparisons were corrected using a false discovery rate method with a corrected threshold of P < 0.05.

The mean gFCD and GMV values of each cluster, with significant group differences in gFCD, were extracted for each subject and used for region of interest (ROI)-based group comparisons. To clarify if the regions with altered gFCD also showed structural impairment, we first tested the group differences in GMV for each ROI using two-sample t-tests after controlling for age and sex. The group differences in gFCD were then tested using two-sample t-tests, after further regressing out the GMV influences, to investigate their separate contributions to functional aberrances in schizophrenia. Finally, a partial correlation coefficient was used to test the relationship between gFCD and GMV in each group, and to test the associations between gFCD and clinical variables, including antipsychotic dose (chlorpromazine equivalents), illness duration, and PANSS scores. Age and sex effects were regressed out and multiple comparisons were corrected using the Bonferroni method (P < 0.05).

Results

Subject demographics and clinical characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant group differences in sex (χ2 = 1.35, P = 0.25) or age (t = 0.48, P = 0.63). Eighty-seven patients received medication during the MRI examinations, with the remaining eight patients being treatment naïve. The mean antipsychotic dose (cholorpromazin equivalents) was 446.5 ± 341.6 mg/d for the patients with schizophrenia. The mean duration of illness was 121.4 ± 92.8 months. Mean scores on the PANSS positive, negative, and general psychopathology subscales were 17.1 ± 7.9, 20.3 ± 9.1, and 34.1 ± 10.8, respectively.

Distributed specificity of gFCD hubs in patients and controls

Our results revealed that the strongest gFCD hubs were consistently located in the precuneus, inferior parietal lobe, superior temporal gyrus, medial prefrontal cortex, and dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex in our two groups. Most of the gFCD hubs are located in the default mode network and sensory cortices (Fig. 2). The distribution of the gFCD hubs did not differ between the two groups and was also consistent with the results of Tomasi et al. [24].

gFCD changes in patients with schizophrenia

Voxel-wise analysis showed increased gFCD in the sub-cortical and limbic system areas (including the bilateral putamen, caudate, pallidum, and thalami), the hippocampal/parahippocampal complex, and the supplementary motor area (SMA) (Fig. 3a, Table 2). Decreased gFCD was seen in the posterior cortices, including the bilateral postcentral gyri, precentral gyri, right calcarine sulcus, and the left inferior occipital gyrus lobule in patients with schizophrenia (Fig. 3b, Table 2). ROI-based analyses showed that the differences in gFCD between schizophrenia patients and controls persisted even further regress out the GMV effect, suggesting that gFCD alterations in these ROIs are relatively independent characteristics of schizophrenia.

ROI-based gFCD and GMV comparisons in regions exhibiting group differences in gFCD voxel-based analysis. Note: Error bars indicate the standard deviations of the means. *P < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected. Cal, calcarine gyrus; Cau, caudate; FCD, functional connectivity density; HC, healthy controls; HP, hippocampus; IPL, parietal inferior lobule; ITG, inferior temporal gyrus; PH, parahippocampal gyrus; Post CG, postcentral gyrus; Put, putamen; SMA, supplementary motor area; SZ, patients with schizophrenia; Th, thalamus. (a) Schizophrenia patient's gFCD is increased compareded to healthy controls in sub-cortical regions (with an exception of supplementary motor area) (b) Schizophrenia patient's gFCD is decreased compareded to healthy controls in cortical regions (c) Schizophrenia patient's GMV is decreased compareded to healthy controls in sub-cortical regions (d) Schizophrenia patient's GMV is decreased compareded to healthy controls in cortical regions

Gray matter volume changes in patients with schizophrenia

Decreased GMV was seen only in the bilateral frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital lobule, cingulate cortex, insular, striatum and thalamus in patients with schizophrenia (Fig. 3c and d and Table 3).

Associations between the spatial distributions of gFCD and GMV

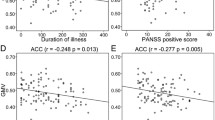

As previously mentioned, increased gFCD were primarily located in subcortical regions, including the basal ganglia and some components of the limbic system and SMA. Decreased gFCD were primarily located in the posterior cortical regions. However, in this study, only decreased GMV was observed. Notably, the aberrant patterns of gFCD and GMV differ between regions. In the caudate, thalami and hippocampus complex (HPC), gFCD increased but GMV decreased, while in the posterior cortices, decreased gFCD accompanied decreased GMV. These findings indicated a complex association between gFCD aberrances and GMV changes in schizophrenia. To further investigate whether gFCD correlates with GMV changes, we also performed correlation. In multiple regions, we found that although gFCD and GMV were both affected, there was no statistical correlation between gFCD and GMV either in patients with schizophrenia patients or controls (Fig. 3).

Association between gFCD/GMV and clinical variables

We did not find any statistical correlation between gFCD or GMV and antipsychotic dose, illness duration, or any PANSS scores (negative, positive, general psychopathology, or total scores).

Discussion

In this study, we first used voxel-wise graph theory to investigate the spatial distribution patterns of gFCD and GMV alterations in a relatively large schizophrenic patient data set. We found that gFCD and GMV were both affected in some regions of the basal ganglia, thalami, limbic system, and posterior cortices, which are the key regions contributing to the pathology of schizophrenia as indicated by several lines of evidence.

More importantly, in our findings, decreased gFCD was found in areas primarily located in the posterior cortical regions, while increased gFCD was observed primarily in areas located in the sub-cortical and limbic system regions. However, only decreased GMV was found in either the cortical or sub-cortical regions in patients with schizophrenia.

In our previous study, we demonstrated for the first time that the gFCD aberrant in schizophrenia, we found increased gFCD in the bilateral striatum and hippocampus and decreased rsFCD in the bilateral sensorimotor cortices and right occipital cortex [27]. Our previous findings added new evidence for supporting the hypothesis that schizophrenia is a connectivity disorder from the perspective of functional connectivity density [27]. And our findings had been confirmed by the subsequent studies [41–43].

As previously mentioned, some cortical regions (e.g., the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, cingulate gyrus, cuneus, and others), limbic system (e.g., hippocampus, parahippocampus, and thalami) and basal ganglia are key regions of functional connectivity and GMV aberrances in schizophrenia. In this study, gFCD and GMV were both affected in most of these regions, but the spatial distribution pattern of gFCD and GMV differed between regions. With the exception of the SMA, in the cortical regions, gFCD and GMV consistently decreased. However, in the sub-cortical regions, the alterations in gFCD and GMV contrasted, with increased gFCD and decreased GMV simultaneously observed in these regions.

Our results suggest that the association between anatomical changes and functional activity aberrances is complex and undefined. Previous studies also demonstrated that structural deficits do not have a straightforward relationship with functional abnormalities [20, 44, 45]. Thus, longitudinal studies aiming to pinpoint the onset of connectivity abnormalities as schizophrenia develops will help clarify the nature of the associations between the structural deficits and functional connectivity alterations in schizophrenia [44].

In this study, we did not found a correlation between aberrant of gFCD/GMV and antipsychotic dose, illness duration, and symptom severity, this finding is consistent with previous studies. and suggest that illness duration, symptom severity, and antipsychotic dose are not linearly related to brain functional or structural abrreant [17, 32, 41, 44]. Our findings suggested that aberrant gFCD and GMV maybe an independent trait characteristic of schizophrenia. Our findings also support the hypothesis that BOLD signal alterations may better track the presence of psychosis rather than its severity or duration [20], and is not linearly related to the antipsychotic dose [46].

Conclusion

This study provides new evidence of aberrant gFCD and decreased GMV in multiple brain regions contributing to the pathology of schizophrenia in a relatively large sample of patients with schizophrenia. More importantly, we revealed that gFCD and GMV are jointly affected in multiple regions, but that their spatial distribution patterns in the intergroup difference maps were dissociated. These findings suggest that structural and functional alterations probably contribute independently to the neurobiology of schizophrenia. However, the nature of the associations between the structural deficits and functional alterations needs clarification using longitudinal studies to pinpoint the onset of connectivity abnormalities as schizophrenia develops.

Abbreviations

- FCD:

-

Functional connectivity density

- gFCD:

-

Global functional connectivity density

- GMV:

-

Gray matter volume

- PANSS:

-

Positive and negative syndrome scale

- SCID:

-

Structural clinical interview for DSM-IV

References

Thompson PM, Vidal C, Giedd JN, Gochman P, Blumenthal J, Nicolson R, Toga AW, Rapoport JL. Mapping adolescent brain change reveals dynamic wave of accelerated gray matter loss in very early-onset schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11650–5.

Hulshoff Pol HE, Schnack HG, Mandl RC, van Haren NE, Koning H, Collins DL, Evans AC, Kahn RS. Focal gray matter density changes in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:1118–25.

Kawasaki Y, Suzuki M, Kherif F, Takahashi T, Zhou SY, Nakamura K, Matsui M, Sumiyoshi T, Seto H, Kurachi M. Multivariate voxel-based morphometry successfully differentiates schizophrenia patients from healthy controls. Neuroimage. 2007;34:235–42.

Tanskanen P, Ridler K, Murray GK, Haapea M, Veijola JM, Jääskeläinen E, Miettunen J, Jones PB, Bullmore ET, Isohanni MK. Morphometric brain abnormalities in schizophrenia in a population-based sample: relationship to duration of illness. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:766–77.

Chakos MH, Lieberman JA, Alvir J, Bilder R, Ashtari M. Caudate nuclei volumes in schizophrenic patients treated with typical antipsychotics or clozapine. Lancet. 1995;345:456–7.

Ebdrup BH, Skimminge A, Rasmussen H, Aggernaes B, Oranje B, Lublin H, Baare W, Glenthoj B. Progressive striatal and hippocampal volume loss in initially antipsychotic-naive, first-episode schizophrenia patients treated with quetiapine: relationship to dose and symptoms. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14:69–82.

Lieberman JA, Tollefson GD, Charles C, Zipursky R, Sharma T, Kahn RS, Keefe RS, Green AI, Gur RE, McEvoy J, Perkins D, Hamer RM, Gu H, Tohen M. Antipsychotic drug effects on brain morphology in first-episode psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:361–70.

Lang DJ, Kopala LC, Vandorpe RA, Rui Q, Smith GN, Goghari VM, Lapointe JS, Honer WG. Reduced basal ganglia volumes after switching to olanzapine in chronically treated patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1829–36.

Pettersson-Yeo W, Allen P, Benetti S, McGuire P, Mechelli A. Dysconnectivity in schizophrenia: where are we now? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1110–24.

Stephan KE, Friston KJ, Frith CD. Dysconnection in schizophrenia: from abnormal synaptic plasticity to failures of self-monitoring. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:509–27.

Friston KJ, Frith CD. Schizophrenia: a disconnection syndrome. Clin Neurosci. 1995;3:89–97.

Zhou Y, Liang M, Tian L, Wang K, Hao Y, Liu H, Liu Z, Jiang T. Functional disintegration in paranoid schizophrenia using resting-state fMRI. Schizophr Res. 2007;97:194–205.

Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Thermenos HW, Milanovic S, Tsuang MT, Faraone SV, McCarley RW, Shenton ME, Green AI, Nieto-Castanon A, LaViolette P, Wojcik J, Gabrieli JD, Seidman LJ. Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1279–84.

Liu F, Zhuo C, Yu C. Altered cerebral blood flow covariance network in schizophrenia. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:308.

Yu R, Hsieh MH, Wang HL, Liu CM, Liu CC, Hwang TJ, Chien YL, Hwu HG, Tseng WY. Frequency dependent alterations in regional homogeneity of baseline brain activity in schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57516.

Turner JA, Damaraju E, van Erp TG, Mathalon DH, Ford JM, Voyvodic J, Mueller BA, Belger A, Bustillo J, McEwen S, Potkin SG, Fbirn, Calhoun VD. A multi-site resting state fMRI study on the amplitude of low frequency fluctuations in schizophrenia. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:137.

Ren W, Lui S, Deng W, Li F, Li M, Huang X, Wang Y, Li T, Sweeney JA, Gong Q. Anatomical and functional brain abnormalities in drug-naive first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1308–16.

He Z, Deng W, Li M, Chen Z, Jiang L, Wang Q, Huang C, Collier DA, Gong Q, Ma X, Zhang N, Li T. Aberrant intrinsic brain activity and cognitive deficit in first-episode treatment-naive patients with schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2013;43:769–80.

Hoptman MJ, Zuo XN, Butler PD, Javitt DC, D’Angelo D, Mauro CJ, Milham MP. Amplitude of low-frequency oscillations in schizophrenia: a resting state fMRI study. Schizophr Res. 2010;117:13–20.

Ikuta T, Robinson DG, Gallego JA, Peters BD, Gruner P, Kane J, John M, Sevy S, Malhotra AK, Szeszko PR. Subcortical modulation of attentional control by second-generation antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2014;221:127–34.

Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Voxel-based morphometry--the methods. Neuroimage. 2000;11:805–21.

Liu F, Guo W, Yu D, Gao Q, Gao K, Xue Z, Du H, Zhang J, Tan C, Liu Z, Zhao J, Chen H. Classification of Different Therapeutic Responses of Major Depressive Disorder with Multivariate Pattern Analysis Method Based on Structural MR Scans. Plos One. 2012;7:e40968.

Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Functional connectivity density mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9885–90.

Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Functional connectivity hubs in the human brain. NeuroImage. 2011;57:908–17.

Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Association between functional connectivity hubs and brain networks. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:2003–13.

Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Mapping small-world properties through development in the human brain: disruption in schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96176.

Zhuo C, Zhu J, Qin W, Qu H, Ma X, Tian H, Xu Q, Yu C. Functional connectivity density alterations in schizophrenia.Front. Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:404.

Liu F, Zhu C, Wang Y, Guo W, Li M, Wang W, Long Z, Meng Y, Cui Q, Zeng L, Gong Q, Zhang W, Chen H. Disrupted cortical hubs in functional brain networks in social anxiety disorder. Clin Neurophysiol. 2015;126:1711–6.

Gong Q, Lui S, Sweeney JA. A selective review of cerebral abnormalities in patients with first-episode schizophrenia before and after treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:232–43.

Guo W, Liu F, Xiao C, Zhang Z, Yu M, Liu J, Liu G, Zhao J. Dissociation of anatomical and functional alterations of the default-mode network in first-episode, drug-naive schizophrenia. Clin Neurophysiol. 2015;126:2276–81.

Jiang T, Zhou Y, Liu B, Liu Y, Song M. Brainnetome-wide association studies in schizophrenia: the advances and future. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:2818–35.

Shepherd AM, Laurens KR, Matheson SL, Carr VJ, Green MJ. Systematic meta-review and quality assessment of the structural brain alterations in schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1342–56.

Walterfang M, Wood SJ, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C. Neuropathological, neurogenetic and neuroimaging evidence for white matter pathology in schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:918–48.

Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage. 2012;59:2142–54.

Liu F, Guo W, Liu L, Long Z, Ma C, Xue Z, Wang Y, Li J, Hu M, Zhang J, Du H, Zeng L, Liu Z, Wooderson Sarah C, Tan C, Zhao J, Chen H. Abnormal amplitude low-frequency oscillations in medication-naive, first-episode patients with major depressive disorder: A resting-state fMRI study. J Affect Disorders. 2013;146:401–6.

Liu F, Guo W, Fouche J-P, Wang Y, Wang W, Ding J, Zeng L, Qiu C, Gong Q, Zhang W, Chen H. Multivariate classification of social anxiety disorder using whole brain functional connectivity. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220:101–15.

Liu Feng, Wang Yifeng, Li Meiling, Wang Wenqin, Li Rong, Zhang Zhiqiang, Lu Guangming, Chen Huafu. Dynamic Functional Network Connectivity in Idiopathic Generalized Epilepsy with Generalized Tonic–Clonic Seizure. Hum Brain Mapp 2017, in press, doi:10.1002/hbm.23430.

Shokri-Kojori E, Tomasi D, Wiers CE, Wang GJ, Volkow ND. Alcohol affects brain functional connectivity and its coupling with behavior: greater effects in male heavy drinkers. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;29 [Epub ahead of print].

Tomasi D, Shokri-Kojori E, Volkow ND. High-resolution functional connectivity density: hub locations, sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and reliability. Cereb Cortex. 2016;26:3249–59.

Tomasi D, Shokri-Kojori E, Volkow ND. Temporal changes in local functional connectivity density reflect the temporal variability of the amplitude of low frequency fluctuations in gray matter. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154407.

Chen X, Duan M, Xie Q, Lai Y, Dong L, Cao W, Yao D, Luo C. Functional disconnection between the visual cortex and the sensorimotor cortex suggests a potential mechanism for self-disorder in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;166:151–7.

Hansen EC, Battaglia D, Spiegler A, Deco G, Jirsa VK. Functional connectivity dynamics: modeling the switching behavior of the resting state. Neuroimage. 2015;105:525–35.

Liu B, Fan L, Cui Y, Zhang X, Hou B, Li Y, Qin W, Wang D, Yu C, Jiang T. DISC1 Ser704Cys impacts thalamic-prefrontal connectivity. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220:91–100.

Fornito A, Zalesky A, Pantelis C, Bullmore ET. Schizophrenia, neuroimaging and connectomics. Neuroimage. 2012;62:2296–314.

Rubinov M, Bassett DS. Emerging evidence of connectomic abnormalities in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6263–5.

Woodward ND, Karbasforoushan H, Heckers S. Thalamocortical dysconnectivity in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1092–9.

Acknowledgements

We would gratefully thank for the patients, their families.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (81425013, 91332113 and 81271551), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Funded Project (2012 M 520585), the Tianjin Key Technology R&D Program (14ZCZDSY00018) and China Potevio Information Industry Co.

Availability of data and materials

Data will not be made available in order to protect the participants identity.

Authors’ contributions

CZ, JZ, and WQ designed the study. CW, HQ, XM, HT and ML acquired and CZ, JZ, and WQ analyzed the data. CZ, JZ, and WQ wrote the article, which all authors reviewed and approved for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics. All participants gave their written informed consent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhuo, C., Zhu, J., Wang, C. et al. Brain structural and functional dissociated patterns in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 17, 45 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1194-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1194-5