Abstract

Background

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic skin disease which has been known to negatively influence the mental health of patients. However, only a few studies have explored the prevalence of psychiatric problems among AD patients, particularly among adolescents. In this study, we aimed to assess the association of AD with depressive symptoms and suicidal behaviors among adolescents by analyzing data from the 2013 Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey, a nationwide web-based survey.

Methods

Data from 72,435 adolescent middle and high school students in Korea were analyzed. Students self-reported AD diagnosed by a doctor and yes-or-no answers to questions about depressive symptoms and suicide ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempts were analyzed. Relationships between AD and depressive symptoms or suicidal behaviors were tested by logistic regression models after controlling for potential confounding factors.

Results

The proportion of adolescents who had AD was 6.8%. The proportion of adolescents reporting depressive feelings was 31.0%, suicide ideation was 16.3%, suicide planning was 5.8%, and suicide attempts was 4.2%. Compared to adolescents without AD, adolescents with AD were significantly more likely to experience depressive feelings (odds ratio [OR]: 1.27, 95% confidence interval [Cl]: 1.19-1.36), suicide ideation (OR: 1.34, 95% Cl: 1.24-1.45), suicide planning (OR: 1.46, 95% Cl: 1.32-1.65), and suicide attempts (OR: 1.51, 95% Cl: 1.33-1.72). In the multivariate model, the relationships between AD and suicide ideation (OR: 1.26, 95% Cl:1.16-1.36), suicide planning (OR: 1.28, 95% Cl:1.14-1.44), and suicide attempt (OR: 1.29, 95% Cl:1.13-1.49) were statistically significant.

Conclusion

Adolescents who have AD are associated with a higher prevalence of depression symptoms and suicidal behaviors. Adolescent AD patients may need interventions from clinicians and caregivers that use a holistic approach to prevent psychological comorbidities, although further research is needed to clarify this relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by pruritic, erythematous lesions, which is typically localized on flexural areas, the face, or the hands and which usually manifests in early childhood [1]. The worldwide prevalence of AD is 10%-20%, and it has significantly increased during the last three decades [2]. In Korea, its prevalence is estimated to be about 10% in the pediatric population less than 6 years of age and about 3% among adults [3]. In the Eighth Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey (KYRBS), a nation-wide web-based survey, conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2012, 24% of adolescents responded that they had ever been diagnosed with AD [4]. The pathophysiological mechanisms of AD are not well understood; however cumulative evidence has shown that interactions between systemic and local immunologic responses, defects in skin barrier function, susceptibility genes, and the host’s environment are involved in producing AD symptoms [2]. The risk factors that contribute to an increased prevalence of AD include female sex [5], young age [5], higher socioeconomic status [6], smaller family size [7], and residence in an urban environment [8].

Dermatologic disorders such as AD are not fatal, but the resulting irritation, sleep disturbances due to itching and sensation of heat increase AD patients’ psychological burden [9]. Additionally, people often comment on their appearance, and many of these patients feel socially isolated, all of which may decrease their quality of life [10]. It has been reported that AD patients feel relatively high levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms [11], and chronic dermatologic illnesses can be associated with depression and suicide ideation [12]. In the late 1990s, a case-control study reported that children aged 5-15 years with moderate or severe AD scored twice as high as children without AD on a psychological disturbances scale. [9]. In another study, patients aged 16-56 years scored higher than normal controls on a self-reported depression scale, and their scores increased according to the severity of their AD [11]. Several cross-sectional, population-based studies of adult women and men have consistently reported an elevated risk for depression among participants with AD, and the strengths of the associations varied depending on the severity of AD symptoms (odds ratios [ORs]: 1.31-6.28) [13–15].

A large population-based survey in 2012 based on children aged under 18 years in the United States showed higher odds ratios (ORs) for depression in children with AD compared to children without AD (OR: 1.81, 95% Cl: 1.33-2.46) [16]. The same study also found a dose-response relationship between the prevalence of depression and the severity of AD symptoms. However, the study did not assess the associations between AD and suicidal behaviors.

The period of adolescence is known to be associated with high levels of psychological burden and vulnerability to depression [17–19]. Depression is one of the most significant risk factors for suicide. [20–22]. In 2012, it was reported that the prevalence of depressive symptoms experienced by the Korean population over 19 years of age was 12.9% [23], whereas the prevalence among adolescents was 30.5% [4]. In addition, the proportion of adolescents who experienced suicide ideation was 18.3%, suicide planning was 6.3%, and suicide attempts was 4.1% [4]. According to a report concerning suicide rate in Korea, the suicide rate in the children and youth category (10-24 years old) has been increased by 47% from 2000 to 2010, while the average suicide rate of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries decreased by 16% during the same period [24].

Although there have been concerns about mental health among adolescents, very few studies have attempted to examine the relationship between AD and psychiatric symptoms in the general adolescent population aged 10-18 years. In a study using the Eighth KYRBS, the authors reported on the associations between atopic dermatitis and suicidal behaviors in girls. They concluded that the higher risk of suicidal behavior in girls was due to their higher prevalence of distorted weight perception. The association with depressive symptoms was not described, and the strength of the relationship was somewhat weak, which might be attributed to the question used to assess AD in the Eighth KYRBS (“Have you ever been diagnosed with atopic dermatitis by a doctor at any point in your life?”). The question asked whether the participants had ever been diagnosed with AD, regardless of their current symptoms, which led to the higher rate of AD mentioned above (24%) [25]. In the Ninth KYRBS, an additional question on whether the participants had been diagnosed in the past 1 year was added, which is more relevant for describing current mental health concerns and its association with AD. In this study, we assessed the association between AD and symptoms of depression or suicidal behaviors in an adolescent population living in Korea using data from the Ninth KYRBS.

Methods

Data source

This study analyzed data from Ninth KYRBS 2013 [26], which is conducted every year under Article 19 of the National Health Promotion Law by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korean Ministry of Education at the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The survey comprises 15 sections (Smoking, Drinking, Physical activity, Diet, Obesity and weight control, Mental health, Injuries and safety awareness, Oral health, Personal hygiene, Drug use, Sexual behavior, Atopy and asthma, Internet addiction, Socioeconomic status, and Violence) that were developed based on other studies conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Ninth KYRBS gathered responses from sample population, who were 75,149 middle and high school students in Korea, about risk behaviors such as cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption. The study has been granted an exemption from ethics approval, since it used open-access public data (exemption approval: Seoul National University Hospital IRB # 1508-110-696).

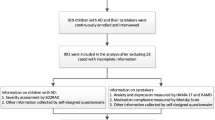

Study population

The study population was defined as middle or high school students living in Korea in April 2012. The population was stratified by 43 regions and school type, and then the number of sample schools in each region was determined according to the composition of the target population. Using stratified cluster sampling, 800 sample schools were systematically selected. Then sample classes were selected randomly and every student in the class, except for exceptional cases such as long-term absentee, students with disability, were included in the final dataset. The survey targeted 75,149 students from 400 middle schools and 400 high schools, and the participation rate was 96.4%. The reasons for non-participation were not available. A total of 72,435 students at 799 schools were included in the analysis, and there was no non-response because the survey system was designed to answer every question. However, some of the data was considered as missing value if there was any logical error or if it was outlier. For example, the respondent from a boy school answered as ‘Female’, then the answer was processed as a missing value. The proportion of missing values was about 2%.

Study variables

The diagnosis of AD was evaluated by an affirmative response to the question “During the past 12 months, have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care provider that you had atopic dermatitis?”. Depression symptoms, suicide ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempts were assessed by the following questions: “During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities?”, “During the past 12 months, have you ever seriously thought of committing suicide?”, “During the past 12 months, have you ever made a plan about how you would attempt suicide?”, and, “During the past 12 months, have you ever attempted suicide?”.

The potential confounders considered were sex, age (12 ~ 14 years (middle school)/15 ~ 17 years (high school))[2, 27], area of residence (rural/urban area)[8, 28], family affluence (low/middle/high), parental education (<high school graduation/high school graduation/>college graduation)[6, 29], sleep duration (<5 hours/5-7 hours/>7 hours), sleep satisfaction (well enough/enough/not enough) [9, 30], violence (never experienced/experienced ≥ 1 time) [31, 32], and alcohol consumption (individuals with problem drinking/drinker/non-drinker) [33, 34] which were known to be associated with AD and depression. Additionally, only a little evidence supports the association with AD, vigorous physical activity (do/do not ≥ 1 per week) [35], and smoking (non-smoker/smoke <10 cigarettes per day/smoke ≥10 cigarettes per day) [36] were also considered as the confounders.

All questions and their multiple-choice answers for each issue were set by the KYRBS 2013 [37]. We categorized the answers based on known knowledge about potential relationships with AD or depression. Respondents who lived in the county or rural areas were categorized as ‘Rural’; those who lived in small, middle-sized or large cities were categorized as ‘Urban’. Family affluence was calculated by a four-item measure of family wealth that considered the number of family cars, holidays, personal computers, and bedrooms; a score of 0-2 was categorized as ‘Low’, 3-5 was categorized as ‘Middle’, and over 6 was categorized as ‘High’ [38]. The respondents’ father’s and mother’s education were considered separately. Vigorous physical activity was defined as exercising for more than 20 minutes causing rapid breathing and a substantial increase in heart rate [26]. Because exercise duration rather than frequency is a critical factor for developing depressive feelings [39], participation in vigorous physical activity was categorized as ‘Do ≥ 1 per week’ or ‘Do not’. For smoking, heavy smokers were defined as those who smoked over 10 cigarettes per day on average during the last 30 days [26]. For alcohol consumption, ‘drinker’ was defined as respondents who drank at least 1 shot glass of alcohol during the last 30 days, and ‘non-drinker’ was defined as those who did not drink during the last 12 months or had no experience drinking alcohol [26]. Since it is well known that alcohol is correlated with depression [33], we further categorized respondents who drank alcohol and who experienced alcohol-related problems, such as dependence on alcohol, loss of memory or causing trouble with other people when drunk, during the last 12 months as an ‘individuals with problem drinking’. [26]. Sleep duration was calculated by using the bedtime and wake-up time reported by respondents during the last 7 days. There were 5 choices (well enough/enough/so-so/not enough/never enough) for the sleep satisfaction question [26]. The first two were grouped into a single category (‘enough’), as were the last two (‘not enough’). Respondents were categorized as having experienced violence if they reported experiencing physical and/or psychological violence such as bullying or threatening by others at least once during the last 12 months [26].

Statistical methods

The univariate analysis was conducted to estimate the prevalence of AD and each mental health condition by the various sociodemographic factors. The association of AD with the presence of depression symptoms and suicidal behaviors was assessed by using the χ2 test between the AD and non-AD groups. Logistic regression models were used to further assess the relationship between the variables by calculating the ORs and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Of the potential confounding factors, those that were significantly associated with AD were entered one by one into the regression model, which included AD as an independent variable. The factors that substantially changed the ORs (over 10%) between AD and depression symptoms, suicidal ideation, or suicidal planning were planned to be included in the multivariate logistic regression model; however, none of the factors had a significant impact on the results. Therefore, only sex and age were entered in the logistic regression model. Additionally, the results of the multivariate logistic regression model that includes other potential confounders and depression symptom, with the exception of participation in physical activity and cigarette smoking, were presented. Because the associations between AD and mental health outcomes were insignificant among boys in a previous study, the ORs were further assessed stratified by sex to determine if there were any differences between both sexes. All analyses were conducted by applying strata, cluster, and weight procedures to properly estimate the variance and were performed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States).

Results

The prevalence of AD diagnosed during the past year among the adolescent study population was 6.8%. The proportion of adolescents reporting having had depression symptoms was 31.0%, suicide ideation was 16.3%, suicide planning was 5.8%, and suicide attempts was 4.2%. The characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Those with AD had a higher prevalence of having female gender (P < 0.001), living in urban area (P = 0.002), higher family affluence score (P < 0.001), parents with higher educational attainment (P < 0.001 for father’s education; P = 0.009 for mother’s education), drinking problem, (P = 0.002), shorter sleeping duration (P < 0.001), unsatisfactory sleep (P < 0.001), and violence experience (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences between middle and high school students. There were no significant differences between middle and high school students.

In the same way, the distribution of sociodemographic characteristics among those with and without each mental health condition was assessed as shown in Table 2. All differences were significant except for those of suicidal behaviors between residence area and physical activity. Those who had depression symptoms and suicidal behaviors had a higher prevalence of being female gender, older age, lower family affluence score, having parents with lower educational attainment, smoking problem, drinking problem, short sleeping period, unsatisfactory sleep, and violence experience (P < 0.01 for all factors).

Associations between AD and ‘had depression symptoms’ are shown in Table 3. Among adolescents with AD, there were higher prevalences of those who had felt sadness and hopelessness (OR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.20–1.37), considered suicide (OR: 1.31, 95% CI: 1.21-1.42), planned suicide (OR: 1.42, 95% CI: 1.26-1.61), or attempted suicide (OR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.32-1.73) than adolescents without AD. When other potential confounders were included in the final logistic regression model, the adjustment had little impact on the association of AD with having depression symptoms (OR: 1.24, 95% Cl: 1.15-1.34). On the other hand, the confounders significantly affected the relationship between AD and suicide ideation (OR: 1.23, 95% Cl:1.13-1.35), suicide planning (OR: 1.29, 95% Cl:1.13-1.48), and suicide attempt (OR: 1.31, 95% Cl:1.12-1.52).

The relationship was analyzed by stratifying data by sex (Table 4), and similar OR values were observed with regard to depressive symptoms (OR: 1.21, 95% Cl: 1.07-1.37 for male, OR: 1.25, 95% Cl: 1.14-1.38 for female), suicide ideation (OR: 1.20, 95% Cl: 1.02-1.40 for male, OR: 1.25, 95% Cl: 1.12-1.39 for female), suicide planning (OR: 1.23, 95% Cl:0.99-1.52 for male, OR: 1.33, 95% Cl; 1.13-1.57 for female), and suicide attempt (OR: 1.37, 95% Cl: 1.04-1.80 for male, OR: 1.28, 95% Cl: 1.08-1.53 for female). In addition, interaction p-values for sex on the associations between AD and mental health variables were not statistically significant (data not shown).

When depression symptoms were included as a variable in the model of AD and suicidal behaviors, the associations became weaker but still remained significant (OR: 1.14, 95% Cl: 1.03-1.26 for suicide ideation, OR: 1.20, 95% Cl: 1.05-1.38 for suicide planning, OR: 1.22, 95% Cl: 1.04-1.42 for suicide attempt).

Discussion

This study found an association between AD and depression symptoms and suicidal behaviors. The prevalence of those who ‘had depression symptoms’, have considered suicide, planned suicide and attempted suicide were higher among students with AD. And a similar strength of association was observed in both male and female students. These results confirm and expand upon previous findings on the relationship between mental health and AD.

The prevalence of AD in this study was 6.8% which is similar to the previous findings [3]. However, we found no significant differences in the prevalence of AD of between middle school students and high school students, which is not consistent with other findings that the prevalence of AD decreases with age [40–43]. This finding may be partly explained by the fact that students were living in a similar social environment and that the types of school did not exactly reflect the participants’ age.

Our findings on associations between AD and ‘had depression symptoms’ and suicidal thoughts are consistent with the results of previous population-based surveys [13–16]. However, in our study, the strength of the relationship was somewhat weaker than in other studies. This may be due to differences in the composition of the study population. For example, in a population-based study in the United States of a young population (<17 years) [16], 71% of the study population and about 41% of AD patients were under the age of 13. Consistent with the natural course of AD, patients tended to be younger and incidence decreased with age [42, 43]. Most other studies [9, 11, 12] were case-control studies with small-sized study population. In addition, unlike other studies, we used self-reported ‘had depression symptoms’, not depression diagnosed by a physician. These differences in research methods may explain the weaker relationship that we found.

Despite this, our results were statistically significant. Not every depressive patient develops suicidal behaviors, although 77% of students in our study who answered ‘yes’ to having depression symptoms also answered ‘yes’ to the question on suicide ideation. The ORs for each relationship increased as the clinical severity of the dependent variable increased (e.g., a suicide attempt was considered more severe than suicide ideation). One of the most significant contributing factors associated with adolescent suicide is major depression [20, 21]. Thus, interpreting these variables as interrelated depression symptoms can explain the trends found in this study, which needs further exploration. However, after adjusting for all potential confounding factors, the ORs for suicide ideation, planning, and attempt became weaker when compared to the sex and age-adjusted ORs. Additionally, the ORs for suicidal behaviors changed more substantially than the OR for ‘had depression symptoms’, which could mean that those confounding factors influenced the relationship when combined.

On the other hand, our results do not imply the direction of relationship. Although the mechanisms supporting the relationship between AD and depression are not well established, there are hypotheses supporting both directions. First, it is known that certain personality types and psychological stresses are contributing factors for developing AD. Stress-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and autonomic nervous system responses followed by immunologic disturbances are the underlying mechanisms [44]. Thus, stressful conditions may increase the severity of AD symptoms. In addition, an individual’s psychological state may also affect AD, explaining the association of AD with depression symptoms and suicidal behaviors.

A study based on Finnish twins showed that AD patients are genetically vulnerable to depressive disorders [45]. This means that depression symptoms may not be a consequence of AD and that it may be difficult to prevent depression symptoms among AD patients. On the other hand, sleep loss caused by itching and scratching during the night may negatively affect patients’ quality of life and lead to the development of depression [46]. Physical fatigue due to sleep disturbance during the night, as well as other factors including greater feelings of helplessness because of the illness and less social acceptance, have been found to be significantly related to high levels of psychological distress among AD patients [47]. This presents the possibility of developing treatment strategies for coping with the psychological distress of AD patients.

There are some fundamental limitations of this study, which should be considered when interpreting its results. First, we did not use AD as diagnosed by a caregiver or clinician, which may have led to a misclassification of AD. Thus, there is a possibility that the prevalence of AD in our study population was underestimated. Using a clinical diagnosis of AD would strengthen our findings. Meanwhile, self-reported allergies have been reported to have good correlations with medical records [48], and many studies have used the self-reported AD as a study variable. It is possible that the strength of the relationship between AD and experiencing depression symptoms was exaggerated. Due to the presence of depression symptoms, these individuals may have visited a doctor more often, which could have led to their AD being diagnosed more readily than AD patients without depression symptoms.

Second, we used self-reports of ‘had depression symptoms’ rather than a clinical diagnosis of depression. A two-week period of persistent depressive feelings or suicidal behaviors is considered to be a criterion but is not sufficient for a definite diagnosis of depression [49]. For example, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV), includes questions on whether patients have had anhedonia, sleep disturbances, appetite changes, weight changes, fatigue, or a sense of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt [49]. Other studies have used a diagnosis of depression by a physician or a self-reported scale of depression symptoms based on questionnaires with multiple diagnostic questions. By using simplified diagnostic criteria, the prevalence of depression symptoms in our population may have been overestimated. The prevalence of diagnosed depression is generally lower than that of depression symptoms. For example, in Korea, the prevalence of depression is reported to be 3.6%-5.5% [50] compared with the 31% prevalence of depression symptoms in our study population [26]. However, there is also a possibility of underestimation. Depression in Asian countries tends to be expressed as somatized symptoms, rather than affective complaints [51]. Additionally, adolescent depression may present as substance abuse or disruptive behaviors, which we could not assess in this study, and it may be underdiagnosed due to a lack of healthcare [52]. As a result, the population we extracted as having depression symptoms and showing suicidal behaviors may not represent the population with depression disorders, and this could have over- or under-estimated the strength of the relationship between AD and depression.

Despite these limitations, this study was based on a large sample size from a nationwide general adolescent population survey that has shown good representativeness and generalizability. In addition, we used depressive feelings, suicide ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempts as variables to indicate psychological distress and identify the consistency of relationships with AD. This finding is noteworthy, because it implies that AD may lead to destructive outcomes, such as major depressive disorders or suicide, which could be prevented, if suspected early. Depression is regarded as the most important risk factor for suicide [20–22], which is the fourth leading cause of death in Korea [53]. Levels of psychological distress are known to be relatively higher among adolescents, because the brain during this period undergoes significant development, which makes it exceptionally vulnerable to stress [19]. Adding to that, the prevalence of depressive symptoms and suicidal behaviors is higher among the Korean adolescent population compared with Western countries, which is thought to be the result of higher levels of pressure on studying and less time devoted to leisure [54, 55]. Evaluating and managing psychological problems needs to be emphasized more firmly in this kind of social environment.

Conclusions

In conclusion, students with AD are prone to depressive feelings, and ideation, planning, attempts at suicide. Future longitudinal studies are needed to explore the direction of the relationship of interest. However, regardless of how AD is related to depression, depressive symptoms should be considered an important comorbidity of AD and taken into consideration in clinical practice. Clinicians should be cautious with regard to psychological issues when dealing with adolescent AD patients. There are no standardized clinical guidelines for treatment of psychological issues. However, patients with AD may benefit from multidisciplinary treatment plans that manage psychological symptoms. Treatment options that focus on fatigue reduction, changing patients’ pessimistic attitudes about their disease, and promoting social support have been developed and tested in a few studies and have found to be effective enough to relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life of children and adolescent patients with AD [47, 56, 57].

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Atopic dermatitis

- KYRBS:

-

the Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey

References

Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy, 5th edn. London: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009.

Leung DY, Boguniewicz M, Howell MD, Nomura I, Hamid QA. New insights into atopic dermatitis. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(5):651–7.

Kim K. Current status and characteristics of atopic dermatitis in Korea. J Korean Medical Assoc. 2014;57(3):208–11.

Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey. The Ninth Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey 2012. In. Edited by Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey; 2012.

Carson CG. Risk factors for developing atopic dermatitis. Dan Med J. 2013;60(7):B4687.

Mercer MJ, Joubert G, Ehrlich RI, Nelson H, Poyser MA, Puterman A, Weinberg EG. Socioeconomic status and prevalence of allergic rhinitis and atopic eczema symptoms in young adolescents. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2004;15(3):234–41.

Bodner C, Godden D, Seaton A. Family size, childhood infections and atopic diseases. Aberdeen WHEASE Group Thorax. 1998;53(1):28–32.

Bråbäck L, Kälvesten L. Urban living as a risk factor for atopic sensitization in Swedish schoolchildren. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1991;2(1):14–9.

Absolon CM, Cottrell D, Eldridge SM, Glover MT. Psychological disturbance in atopic eczema: the extent of the problem in school-aged children. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(2):241–5.

Lewis-Jones S. Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(8):984–92.

Hashiro M, Okumura M. Anxiety, depression, psychosomatic symptoms and autonomic nervous function in patients with chronic urticaria. J Dermatol Sci. 1994;8(2):129–35.

Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(5):846–50.

Sanna L, Stuart AL, Pasco JA, Jacka FN, Berk M, Maes M, O'Neil A, Girardi P, Williams LJ. Atopic disorders and depression: findings from a large, population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2014;155:261–5.

Timonen M, Jokelainen J, Hakko H, Silvennoinen-Kassinen S, Meyer-Rochow VB, Herva A, Rasanen P. Atopy and depression: results from the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8(8):738–44.

Klokk M, Gotestam KG, Mykletun A. Factors accounting for the association between anxiety and depression, and eczema: the Hordaland health study (HUSK). BMC Dermatol. 2010;10:3.

Yaghmaie P, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL. Mental health comorbidity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(2):428–33.

Selemon LD. A role for synaptic plasticity in the adolescent development of executive function. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e238.

Andersen SL, Teicher MH. Stress, sensitive periods and maturational events in adolescent depression. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(4):183–91.

Andersen SL. Trajectories of brain development: point of vulnerability or window of opportunity? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27(1-2):3–18.

Kim HS, Kim HS. Risk factors for suicide attempts among Korean adolescents. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2008;39(3):221–35.

Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Allman C, Friend A, Roth C, Schweers J, Balach L, Baugher M. Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: a case-control study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(3):521–9.

Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, Borges G, Bromet E, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, et al. Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000123.

Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea Health Statistics 2012: Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES V-3). In. Edited by Ministry of Health and Welfare: Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012;161.

Jin J, Go H. The Korean suicide rate trend by population group comparing with the OECD countries and its policy implications. In: Health and Welfare Policy Forum: 2013;2013:141–54.

Noh H-M, Cho JJ, Park YS, Kim J-H. The relationship between suicidal behaviors and atopic dermatitis in Korean adolescents. J Health Psychol. 2015;1359105315572453.

Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey. The Ninth Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey 2013. In. Edited by Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey; 2013.

Lehtinen V, Joukamaa M. Epidemiology of depression: prevalence, risk factors and treatment situation. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1994;377:7–10.

Beekman A, Copeland J, Prince MJ. Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174(4):307–11.

Goodman E, Slap GB, Huang B. The public health impact of socioeconomic status on adolescent depression and obesity. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(11):1844–50.

Adrien J. Neurobiological bases for the relation between sleep and depression. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6(5):341–51.

Flannery DJ, Wester KL, Singer MI. Impact of exposure to violence in school on child and adolescent mental health and behavior. J Community Psychol. 2004;32(5):559–73.

Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY. The Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132(6):942–9.

Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Tests of causal links between alcohol abuse or dependence and major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(3):260–6.

Vally H, Thompson PJ. Alcoholic drink consumption: a role in the development of allergic disease? Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33(2):156–8.

Lucas M, Mekary R, Pan A, Mirzaei F, O'Reilly EJ, Willett WC, Koenen K, Okereke OI, Ascherio A. Relation between clinical depression risk and physical activity and time spent watching television in older women: a 10-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(9):1017–27.

Pasco JA, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, Ng F, Henry MJ, Nicholson GC, Kotowicz MA, Berk M. Tobacco smoking as a risk factor for major depressive disorder: population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(4):322–6.

The guideline for users. KYRBS 2013. In. Edited by Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013.

World Health Organization: Inequalities in Young People's Health: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) International Report from the 2005/2006 Survey. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2008;14.

Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, Kampert JB, Clark CG, Chambliss HO. Exercise treatment for depression: efficacy and dose response. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(1):1–8.

Hong S, Son DK, Lim WR, Kim SH, Kim H, Yum HY, Kwon H. The prevalence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis and the comorbidity of allergic diseases in children. Environ Health Toxicol. 2012;27:e2012006.

Williams HC, Strachan DP. The natural history of childhood eczema: observations from the British 1958 birth cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(5):834–9.

Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, Nickel R, Gruber C, Niggemann B, Wahn U, Multicenter Allergy Study G. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(5):925–31.

Ricci G, Patrizi A, Baldi E, Menna G, Tabanelli M, Masi M. Long-term follow-up of atopic dermatitis: retrospective analysis of related risk factors and association with concomitant allergic diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5):765–71.

Buske-Kirschbaum A, Geiben A, Hellhammer D. Psychobiological aspects of atopic dermatitis: an overview. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70(1):6–16.

Wamboldt MZ, Hewitt JK, Schmitz S, Wamboldt FS, Rasanen M, Koskenvuo M, Romanov K, Varjonen J, Kaprio J. Familial association between allergic disorders and depression in adult Finnish twins. Am J Med Genet. 2000;96(2):146–53.

Slattery MJ, Essex MJ, Paletz EM, Vanness ER, Infante M, Rogers GM, Gern JE. Depression, anxiety, and dermatologic quality of life in adolescents with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(3):668–71.

Evers AW, Lu Y, Duller P, van der Valk PG, Kraaimaat FW, van de Kerkhof PC. Common burden of chronic skin diseases? Contributors to psychological distress in adults with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152(6):1275–81.

Kriegsman DM, Penninx BW, van Eijk JT, Boeke AJ, Deeg DJ. Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. A study on the accuracy of patients' self-reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1407–17.

American Psychiatry Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition. In: Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes, Depressive Disorders. Washington, DC. 2013;125.

Park JH, Kim KW. A review of the epidemiology of depression in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2001;28(1):1–8.

Yoo SK, Skovholt TM. Cross-cultural examination of depression expression and help-seeking behavior: A comparative study of American and Korean college students. J Coll Couns. 2001;4(1):10–9.

Hoagwood K, Olin SS. The NIMH blueprint for change report: research priorities in child and adolescent mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(7):760–7.

Korea Statistics. The Statistics of Causes of Death in Korea, 2013. Korean Statistical Information Service: Statistics Korea; Daejeon, 2013.

Meery Lee RL. The Korean ‘Examination Hell’: Long Hours of Studying, Distress, and Depression. J Youth Adolesc. 2000;29(2):249–71.

Lee M. Korean adolescents’ “examination hell” and their use of free time. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2003;99:9–21.

Staab D, Diepgen TL, Fartasch M, Kupfer J, Lob-Corzilius T, Ring J, Scheewe S, Scheidt R, Schmid-Ott G, Schnopp C, et al. Age related, structured educational programmes for the management of atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents: multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332(7547):933–8.

Ehlers A, Stangier U, Gieler U. Treatment of atopic dermatitis: a comparison of psychological and dermatological approaches to relapse prevention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(4):624–35.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate Korean Youth Health Risk Behavior Survey for the approval of using the Eighth KYRBS data.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from Seoul National University Hospital (2015).

Availability of data and materials

The KYRBS annual reports are accessible at the ‘Korea Youth Risk Behavior Survey’ website (http://yhs.cdc.go.kr) and user manuals, and raw dataset supporting the conclusions of this article are also available at the website through email request.

Authors’ contributions

SL and AS conceived and designed the study; SL conducted data analysis and drafted the manuscript; AS critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was provided by every participant in the Ninth KYRBS survey. Personal information was not collected and the results of the survey were not presented to each school.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S., Shin, A. Association of atopic dermatitis with depressive symptoms and suicidal behaviors among adolescents in Korea: the 2013 Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey. BMC Psychiatry 17, 3 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1160-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1160-7