Abstract

Background

It is well documented that a disproportionate number of homeless adults have childhood histories of foster care placement(s). This study examines the relationship between foster care placement as a predictor of adult substance use disorders (including frequency, severity and type), mental illness, vocational functioning, service use and duration of homelessness among a sample of homeless adults with mental illness. We hypothesize that a history of foster care predicts earlier, more severe and more frequent substance use, multiple mental disorder diagnoses, discontinuous work history, and longer durations of homelessness.

Methods

This study was conducted using baseline data from two randomized controlled trials in Vancouver, British Columbia for participants who responded to a series of questions pertaining to out-of-home care at 12 months follow-up (n = 442). Primary outcomes included current mental disorders; substance use including type, frequency and severity; physical health; duration of homelessness; vocational functioning; and service use.

Results

In multivariable regression models, a history of foster care placement independently predicted incomplete high school, duration of homelessness, discontinuous work history, less severe types of mental illness, multiple mental disorders, early initiation of drug and/or alcohol use, and daily drug use.

Conclusions

This is the first Canadian study to investigate the relationship between a history of foster care and current substance use among homeless adults with mental illness, controlling for several other potential confounding factors. It is important to screen homeless youth who exit foster care for substance use, and to provide integrated treatment for concurrent disorders to homeless youth and adults who have both psychiatric and substance use problems.

Trials registration numbers

Both trials are registered with the International Standard Randomized Control Trial Number Register and were assigned ISRCTN57595077 (Vancouver At Home Study: Housing First plus assertive community treatment versus congregate housing plus supports versus treatment as usual) and ISRCTN66721740 (Vancouver At Home Study: Housing First plus intensive case management versus treatment as usual) on September 9, 2012.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The childhoods of homeless adults are disproportionately characterized by persistent poverty, residential mobility, school problems, and other stressful and/or traumatic events [1,2], particularly among homeless individuals with mental illness [3]. One of the earliest identifiable precursors to homelessness may be placement in out-of-home or foster care. Studies of youth “aging out” of the foster care system indicate that between 11% and 36% [4,5] experience street homeless and approximately one-third live with family, friends or acquaintances because they cannot afford permanent housing [6]. In fact, many youth are discharged from foster care without a place to live [6].

In addition to challenges around finding stable housing, many youth exiting foster care do not complete high school and have difficulty finding employment [7,8]. Underlying difficulties related to the transition to adulthood among youth leaving foster care is a cumulative history of trauma, abuse and neglect that results in a number of neurobiological and behavioural deficits including poor social support and coping skills [9,10] as well as risk for further abuse and victimization [8]. Once homeless or “drifting”, street culture promotes antisocial behavior, including association with deviant peers and means of subsistence (e.g., sex trade, theft, drug dealing) [11]. The cumulative impact of these factors places youth at high risk for a wide range of health and psychosocial problems including substance misuse and chronic homelessness [12].

A large body of evidence suggests that adverse childhood experiences, which typically include physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, neglect, dysfunctional family environments, and unstable family structure, are linked to later biological, psychological and social functioning and may affect multiple domains of health and well-being [12-14]. Moreover, it appears that adverse childhood experiences tend to cluster together [15,16] and the number of adverse experiences may be more predictive of negative adult outcomes than particular categories of events. Tsai, Edens and Rosenheck [17] examined the childhood profiles of 738 homeless adults and found three clusters: numerous childhood problems (21%); disrupted family structure (44%); and few childhood problems (35%). Participants with histories of foster care were significantly more likely to fall into the ‘numerous childhood problems’ category, which in turn predicted younger age when first homeless and more severe drug use than other participants. Tam, Zlotnick and Robertson [18] examined the long-term effects of adverse childhood experiences on adult substance use, social service use, and employment among homeless adults in Oakland. Adverse childhood experiences were positively correlated with consistent substance use over 15 months of follow-up as well as social service use. Further, consistent substance use was negatively associated with employment and social service use. However, this latter study did not separate foster care from other adverse childhood events, therefore, the contribution of foster care to various outcomes is not clear.

More specifically, research has documented the association between childhood foster care placement and subsequent homelessness [7,11]. Further, research with homeless populations has found that childhood histories of foster care are significantly correlated with psychiatric disorders in adulthood [3,19]. Roos et al. [19] examined the association between foster care history and a range of health and social outcomes among homeless adults with mental disorders, 75% of whom were Aboriginal, in Winnipeg, Canada. Compared to participants without histories of foster care, those placed in care were significantly more likely to be young, female, less educated, married/cohabitating, Aboriginal, and reported a longer lifetime duration of homelessness. A history of foster care independently predicted a range of adult outcomes including depression, psychosis, substance dependence and interpersonal violence. While various forms of interpersonal violence were examined, different types and frequencies of substance use were not included. A more in depth examination of the impact of foster care on various aspects of substance use is required.

In this study, we focus on the relationship between foster care placement as a predictor of adult homelessness and associated health and service outcomes among a sample of homeless adults with mental disorders. Specifically, we examine the relationship between foster care history and adult substance use (including age of initiation, frequency, severity and type of substance), mental illness, vocational functioning, service use and duration of homelessness. We hypothesize that a history of foster care predicts earlier, more severe and more frequent substance use, multiple mental disorder diagnoses, discontinuous work history and longer durations of homelessness.

Methods

The Vancouver At Home Study includes two randomized controlled trials involving homeless adults with mental illness in Vancouver, British Columbia. Vancouver At Home is one of five experimental projects investigating Housing First in Canada, funded by the Federal Government [20]. Details related to the trials including eligibility criteria, recruitment, randomization, retention, measures, interventions, and hypotheses have been reported elsewhere [21]. The current study focuses on baseline data from both trials in Vancouver and does not incorporate any longitudinal findings. The two trials are distinguished based on participants’ level of need. Based on an algorithm that included information about diagnosis, community functioning, and service use, participants were assigned to a “high” or “moderate ” need group [20,21].

Eligibility criteria included legal adult status (19 years and older), current mental disorder on the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [22], and being absolutely homeless or precariously housed. The MINI is a structured diagnostic interview that can be administered by non-clinicians and inquires about symptoms related to the following categories: Psychotic Disorder, Mood Disorder with Psychotic Features, Hypo(manic) Episode, Major Depressive Episode, Suicide Risk, Panic Disorder, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, Alcohol Dependence, and Substance Dependence. Absolute homelessness was defined as living on the streets or in an emergency shelter for at least the past seven nights with little likelihood of obtaining secure accommodation in the upcoming month. Precariously housed was defined as living in a rooming house, hotel or other transitional housing; in addition, individuals must have experienced at least two episodes of absolute homelessness in the past year, or one episode lasting for at least four weeks in the past year.

Participants were recruited through referral from over 40 agencies available to homeless adults in Vancouver; the majority was recruited from homeless shelters, drop-in centers, homeless outreach teams, hospitals, community mental health teams, and criminal justice programs. Referral was typically initiated by service providers and a preliminary screening for eligibility (e.g., duration of homelessness, mental health and substance use problems), was conducted via telephone with the referral agent. All participants met face-to-face with a trained research interviewer who explained procedures, obtained informed consent, and confirmed study eligibility. A cash honorarium of $5 was provided to the participant for the screening process. Institutional ethics board approval was obtained through Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia. Data derived through the shared cross-site protocol are owned by the study sponsor (Mental Health Commission of Canada). Approval for use of baseline data from both trials used in this study was granted by the study sponsor. Data that are specific to the Vancouver site (site-specific instruments, administrative data) are retained at the host institution (Simon Fraser University).

If the individual met all study criteria, they were enrolled as a participant and the baseline interview commenced, consisting of a series of interviewer-administered questionnaires including socio-demographic characteristics, psychiatric symptoms, substance use, physical health, service use, and quality of life [21]. Participants received a further cash honorarium of $30 upon completion of the baseline interview, which typically took 90 minutes to complete. The following analyses are based upon data from the baseline questionnaires of 497 participants recruited from October 2009 to June 2011 and data from a series of questions related to out-of-home care, which were administered 12 months after baseline.

Variables of interest

Details associated with out-of-home care were elicited by a series of questions related to personal experiences of out-of-home care and having one’s biological children placed in out-of-home care. First, participants were asked if they ever lived away from their parents prior to age 18 and, if so, the reason for living away from home. Second, participants were asked if they were ever placed in foster care, the reason for the placement, and their age and the duration of the most recent placement. Finally, participants were asked if they had biological children currently or previously placed in foster care or other forms of out-of-home care.

Mental disorders were assessed using the MINI and were grouped, based on convention [23], into a severe cluster, comprised of (at least one) current Psychosis, Mood Disorder with Psychotic Features, and Hypo(manic) Episode, and a less severe cluster comprised of Major Depressive Episode, Panic Disorder, and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Frequency and type of substance use over the past month were recorded using the Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP) [24], a structured interview which inquires about a wide range of substances and the number of days used in the past month, the amount used on a typical day, and the route of administration. Physical illness was assessed by self-report using a checklist of 30 chronic health conditions (lasting longer than six months). Blood-borne infectious disease consisted of positive self-report diagnosis of HIV, Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C. Vocational functioning was assessed via two questions: (1) have you ever had a job that lasted for at least one year? (yes/no) and (2) are you currently employed in paid work? (yes/no) Psychometric properties for all measures are provided in previous manuscripts [20,21].

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics (median and inter-quartile range for continuous variables; frequency and percentage for categorical variables) were used to characterize the sample. All continuous variables included in statistical analyses (i.e., age at randomization, duration of homelessness, age first homeless, age of first drug/alcohol use) were transformed into categorical variables. For dichotomous variables, median values were used as the cut-off point. Comparisons of categorical data between participants who completed or did not complete the foster care items, and those who did or did not report a history of foster care, were conducted using Pearson’s chi-square test.

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to model the independent associations between placement in foster care and a series of outcome variables that were established a priori based on previous literature [6,8,25,26]. Each outcome variable was modeled in both univariate and multivariate settings using placement in foster care as an independent risk factor. Outcome variables that were significant at the p ≤ 0.05 level were considered for the multivariable logistic regression analyses using the same set of controlling variables (i.e., age at randomization, gender, ethnicity, marital status, and level of need), chosen based on previous literature [11]. Both unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported as effect sizes and all p-values are two-sided. IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22) was used to conduct the analyses. Missing values that ranged from zero to 1% for all outcome and controlling variables in the regression analysis were excluded, with the exception of age of first alcohol and drug use. A small minority of participants who reported never using alcohol and/or drugs did not have valid information for these variables (5% and 9% respectively).

Results

In total, 497 participants completed the baseline questionnaires. Of the total sample, 449 participants (90%) were located for the 12 month interview and 442 of those participants provided a valid response when asked if they had ever been placed in foster care. Among 442 participants, only 5 (1%) responded “Don’t know” which was categorized as “No”. An additional 1% of participants declined to respond to the foster care questions and was excluded from the analysis. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics for the full baseline sample (n = 497) and for participants who completed all of the foster care items (n = 442). At baseline, the majority of participants who responded to the foster care items were male (72%) and White (57%); the mean age at randomization was 41.0 (SD = 10.9) years; and the mean age when first homeless was 30.1 (SD = 13.4) years. The median duration of lifetime homelessness was 36 months (IQR: 12–84 months). Compared to participants who did not complete the foster care items (n = 55), those who did were more likely to engage in early alcohol use (before age 14) and less likely to report weekly alcohol use in the month prior to enrollment (p ≤ 0.05). Otherwise, there were no significant differences at baseline between participants who completed vs. did not complete the foster care items.

As shown in Table 2, 59% of participants reported that they lived away from their parents prior to age 18. The primary reasons for living away from home were placement in foster care (37%) and running away from home (25%). Thirty percent of participants reported being placed in foster care as a child, primarily due to parental abuse and/or neglect (38%). The median number of foster care placements was 1.0, the median age of the most recent placement was 10 years, and the median duration of the most recent placement was 18 months. Further, 9% of participants reported having children currently in foster care and 23% reported having children in foster care in the past (see Table 2).

Bivariate comparisons by foster care history (yes/no) are summarized in Table 3. Participants with histories of foster care were significantly more likely to share a particular socio-demographic profile (i.e., female, Aboriginal ethnicity, incomplete high school, younger age at enrollment, have children under age 18, no continuous work history); they also first experienced homelessness at a younger age (before 25 years) and, due to their younger age, reported shorter durations of homelessness (both lifetime and longest single episode). Participants with histories of foster care were significantly more likely to meet criteria for: the less severe cluster of mental disorders (i.e., major depressive episode, panic disorder, PTSD); two or more mental disorders; substance dependence; high suicide risk; early initiation of alcohol and/or drug use (before age 14); current daily drug use; injection drug use; and poly-drug use.

Unadjusted (UOR) and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% CI for variables included in the univariate and multivariable analyses are presented in Table 4. Results from the multivariable logistic regression analyses indicate that foster care history independently predicted incomplete high school (AOR: 2.08), duration of homelessness – lifetime (AOR: 1.60) and longest single episode (AOR: 1.95), age of first homelessness (AOR: 2.36), continuous work history (AOR: 0.62); meeting criteria for the less severe cluster of mental disorders (AOR: 1.62) and two or more mental disorders (AOR: 1.69); early initiation of alcohol (AOR: 2.54) and/or drugs (AOR: 2.49) and current daily drug use (AOR:1.64). A significant positive trend (p > 0.05 and p ≤ 0.10) was observed between a history of foster care and meeting criteria for panic disorder (AOR: 1.63), PTSD (AOR: 1.60), high risk of suicide (AOR: 1.59), daily substance use (AOR: 1.53), daily cannabis use (AOR: 1.74), as well as incarceration (AOR: 1.70) and court appearance (AOR: 1.48) in the past six months.

Discussion

Among our sample of homeless adults with mental illness, we found a significant relationship between a history of childhood foster care placement and a number of indicators of socio-demographic risk, poor mental and physical health, and problematic substance use in adulthood. Foster care history independently predicted incomplete high school, duration of homelessness, discontinuous work history, meeting criteria for a current mental disorder in the less severe cluster, multiple mental disorders, early initiation of alcohol and/or drug use, and daily drug use. Our study is the first to examine a range of different adult substance use outcomes (i.e., type, frequency, poly-substance use, age of initiation) among homeless adults with mental illness and histories of foster care placement.

Foster care placement independently predicted substance use problems in our adult sample, specifically early initiation (before age 14) of drug and/or alcohol use and daily drug use. Abuse of alcohol and other drugs places adolescents at greater risk of homelessness, although it may not be a direct causal factor [27]. Compared to their non-homeless counterparts, homeless youth use substances earlier and with greater frequency [28,29]. Further, Thompson and Hasin [30] reported that homeless youth with histories of foster care were almost nine times more likely to have been in drug treatment than homeless youth without such histories, even after adjusting for demographics, other adverse childhood events, prior arrest, unemployment and educational attainment.

Our findings suggest that daily drug use may be a common mediator for a range of early risk factors [31]. Previous research using our sample of homeless adults with mental disorders found that daily drug use was independently predicted by self-report of childhood learning disabilities [32] and adverse childhood experiences [33]. In the latter study, we found a strong relationship between the breadth of exposure to abuse or household dysfunction during childhood (i.e., the number of adverse childhood events) and a number of indicators of poor mental and physical health as well as problematic substance use in adulthood (e.g., daily drug use). In turn, previous work with the same sample has shown that daily drug use significantly predicts the duration of adult homelessness [34] and the severity of mental health symptoms [35].

The current study did not examine other potential mediators such as self-esteem or shame; however, one could assume that strong manifestations of these psychological states might manifest in the mental disorders examined in our study. Daily drug use and other potential mediators (e.g., emotion regulation skills, access to social support and early intervention, antisocial behaviors) need to be examined in future studies using path-type analysis. Cross-sectional, retrospective data cannot disentangle the unique predictors of homelessness and mental illness, but it is likely that adverse childhood experiences, particularly foster care placement, have both direct and indirect (perhaps mediated by substance use) effects on a range of adult health and social outcomes. Thus, among homeless adults with mental disorders, a history of early and persistent substance abuse may be a key indicator of risk. Our findings support the need for more accessible and integrated care for homeless adults with concurrent disorders.

In addition to substance use problems, a history of foster care independently predicted meeting criteria for a less severe type of mental disorder (i.e., major depressive episode, panic disorder, PTSD) and more than one mental disorder. It makes sense that foster care placement would contribute to mood and anxiety disorders more so than psychosis. However, Roos et al. [19] found that a history of foster care predicted adult psychotic disorders as well as depression and multiple mental disorders. While the disorders comprising our less severe cluster may appear less serious than those in the severe cluster, the disorders in the former cluster can be very debilitating. The fact that foster care predicts meeting criteria for multiple mental disorders suggests that poor psychiatric outcomes in adulthood are related to foster care, and further strengthens the case for integrated treatment for concurrent disorders for this population.

Given that over 1,000 youth exit foster care without a family each year in Canada, services and supports need to be in place to help youth address concurrent psychiatric and substance use problems prior to and after discharge. Organizations that provide services to homeless youth should target those with histories of adverse childhood events, particularly foster care, and tailor services to their collective and individual needs. Approaches such as brief motivational interviewing have been shown to reduce substance use among homeless youth in a variety of settings [36,37] and should be made more widely available as part of integrated treatment for concurrent disorders.

The significant association between foster care history and the duration of homelessness in adulthood is also of concern. Both researchers and advocates have called for more evidence-based interventions to reduce homelessness among youth exiting foster care [8,11]. Preliminary research on transitional living programs for youth exiting foster care is associated with reduced rates of street homelessness and increased employment, particularly when paired with vocational skills training [38].

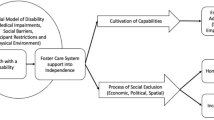

In previous work, we have emphasized the importance of viewing homelessness in the context of cumulative adversity [39] and Problem Behavior Theory [40,41]. These models conceptualize homelessness as the result of successive environmental disruptions, each of which places individuals at greater risk for homelessness and associated risk factors. In addition to the effects of progressive risk, risk may be multiplied at each stage of development because the environmental risks associated with later phases present increasingly greater challenges to development and adaptation. Problem Behavior Theory hypothesizes that various early risk factors may comprise a cluster of risky behaviors that mediate the link from childhood adversity to a variety of adverse adult outcomes, rather than distinct independent pathways. Our findings, alongside others’, suggest that the relationship between foster care placement and adult homelessness (and the associated health and social problems we identified) may be mediated by problem behaviours such as heavy substance use. Further, it is likely that the number of adverse events (e.g., adverse childhood events in addition to foster care, incomplete high school, early problems with substance use and/or the law, lack of institutional or family support) may be more important in predicting negative adult health and social outcomes than any one event. Daily or heavy substance use must be tested as a mediating factor alongside other potential mediators.

Placement in out-of-home care is a significant and salient event that should indicate appropriate interventions for both children and parents. Early interventions in childhood might change or moderate the cycle of homelessness across generations because early risk factors are often longstanding and drive a trajectory of cumulative risk, potentially leading to severe psychopathology and social exclusion. Among our sample of homeless adults, 31% had children currently or previously in foster care, suggesting that foster care placement is a form of trauma that has inter-generational effects.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of our study design (i.e., large sample size, structured diagnostic interviews), several limitations must be considered. First, all variables were based on participant self-report. Given that participants were selected based on presence of a current mental disorder, accuracy of recall may have been compromised. Further, the baseline interview occurred before randomization to a housing intervention and therefore may have led some participants to modify their responses. It is unlikely that participants purposefully modified their responses to the foster care items given that they were administered after the baseline interview. Furthermore, foster care is a highly salient event that is likely to be remembered; however, recall error could have occurred in questions pertaining to the reason for being placed in care.

Additionally, data were not available to examine whether participants’ biological mothers had abused substances during pregnancy, the age participants first entered foster care, the total length of time they spent in foster care, and number and types of residential and educational placements. As each of these factors has been shown to increase the risk for subsequent psychiatric disorders, the effect of these factors on the risk for psychiatric and substance use disorders should be examined in future research. In addition to the above noted variables, we did not have access to several other important variables necessary for conducting a robust path analysis in order to more fully investigate the links between foster care placement and adverse outcomes among homeless adults (e.g., early problem behaviors, social support, affect regulation skills, self-esteem/self-concept, and the availability of treatment/institutional supports). Future longitudinal studies should examine foster care in the context of other adverse childhood events, early problem behaviors that have been identified in the literature (e.g., adolescent substance use, involvement with the law, incomplete high school), as well as key adult outcomes, in order to investigate the key pathways that link foster care to adverse outcomes among homeless adults with mental illness.

Conclusion

This is the first Canadian study to investigate the relationship of a history of foster care with current substance use among homeless adults with mental illness, controlling for several potential confounding factors. The high rates of foster care history observed among our sample of homeless adults with mental illness highlight the dire consequences that can result from this trajectory of risk. Given the salience of removing children from the family home and placing them in foster care, this should be a sentinel event that triggers a range of interventions aimed at preventing negative adult psychiatric, health and social outcomes.

References

Herman D, Susser ES, Struening EL, Link BL. Adverse childhood experiences: are they risk factors for adult homelessness? Am J Pub Health. 1997;87(2):249–55.

Koegel P, Malamid E, Burnam MA. Childhood risk factors for homelessness among homeless adults. Am J Pub Health. 1995;85(12):1642–9.

Sullivan G, Burnam A, Koegel P. Pathways to homelessness among the mentally ill. Soc Psychiatry Epidemiol. 2000;35:444–50.

Brandford C, English D: Foster youth transition to independence study. Seattle: Office of Children’s Administration Research, Washington Department of Social and Health Services; 2004

Reilly T. Transition from Care: The Status and Outcome of Youth Have ‘Aged out’ of the Foster Care System in Clark County, Nevada. Las Vegas: Nevada KIDS COUNT; 2001.

Fowler PJ, Toro PA, Miles BW. Pathways to and from homelessness and associated psychosocial outcomes among adolescents leaving the foster care system. Am J Pub Health. 2009;99:1453–8.

Courtney ME, Dworksy A. Early outcomes for youth people transitioning from out-of-home care in the USA. Child Fam Soc Work. 2006;11:209–19.

Dworsky A, Courtney ME. Homelessness and the transition from foster care to adulthood. Child Welfare. 2009;88:23–56.

DeBellis M, Zisk A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child Adol Psychiatr Clinics N Amer. 2014;23(2):185–222.

Galletly C, VanHoof M, McFarlane A. Psychotic symptoms in young adults exposed to childhood trauma: a 20-year follow-up study. Schizophrenia Res. 2011;127(1–3):76–82.

Penzerro RM. Drift as adaptation: foster care and homeless careers. Child Youth Care Forum. 2003;32(4):229–44.

Zlotnick C. What research tells us about the intersecting streams of homelessness and foster care. Am J Orthopsychiatr. 2009;79:319–25.

Corso PS, Edwards VJ, Fang X, Mercy J. Health-related quality of life among adults who experienced maltreatment during childhood. Am J Pub Health. 2008;98:1094–100.

Dube S, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman D, Giles W, Anda R. Childhood abuse, neglect and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the Adverse Childhood Experience Study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:564–72.

McLaughlin K, Green J, Gruber MJ, Sampson N, Zaslavsky A, Kessler R. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication II: associations with persistence of DSM-IV disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:124–32.

Green J, McLaughlin K, Berglund P, Gruber MJ, Sampson N, Kessler R. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with the onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:113–23.

Tsai J, Edens E, Rosenheck R. A typology of childhood problems among chronically homeless adults and its association with housing and clinical outcomes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22:853–70.

Tam T, Zlotnick C, Robertson M. Longitudinal perspective: adverse childhood events, substance use, and labor force participation among homeless adults. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29:829–46.

Roos L, Distasio J, Bolton S, Katz L, Afifi T, Isaak C, et al. A history in-care predicts unique characteristics in a homeless population with mental illness. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38:1618–27.

Goering PN, Streiner DL, Adair C, Aubry T, Barker J, Distasio J, et al. The At Home/Chez Soi trial protocol: a pragmatic, multi-site, randomised controlled trial of a housing first intervention for homeless individuals with mental illness in five Canadian cities. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000323.

Somers J, Patterson M, Moniruzzaman A, Currie L, Rezansoff S, Palepu A, et al. Vancouver At Home: pragmatic randomized trials investigating housing first for homeless and mentally ill adults. Trials. 2013;14:365.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 20:22–33.

Ruggeri M, Lesse M, Thornicroft G, Bisoffi G, Tansella M. Definition and prevalence of severe and persistent mental illness. Brit J Psychiatr. 2000;177:149–55.

Marsden J, Gossop M, Stewart D, Best D, Farrell M, Strang J: The Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP): a brief instrument for treatment outcome research. Development and User Manual. London UK: National Addiction Centre/ Institute of Psychiatry; 1998. Available at: http://proveandimprove.org.uk/documents/Map.pdf.

Zlotnick C, Tam T, Soman L. Life course outcomes on mental and physical health: the impact of foster care on adulthood. Am J Pub Health. 2012;102:534–40.

Montgomery P, Donkoh C, Underhill K. Independent living programs for young people leaving the care system: the state of the evidence. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2006;28:1435–48.

Sosin MR, Bruni M. Homelessness and vulnerability among adults with and without alcohol problems. Subst Use Misuse. 1997;32(7–8):939–68.

McLean MG, Paradise MJ, Cauce AM. Substance use and psychological adjustment in homeless adolescents: a test of three models. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27:405–27.

Barczyk A, Thompson S. Alcohol/drug dependency in homeless youth. Alcoholism. Clin Experimental Res. 2008;32(s1):367A–367A.

Thompson RG, Hasin D. Cigarette, marijuana, alcohol use and prior drug treatment among newly homeless young adults in New York City: relationship to a history of foster care. Drug Alc Dependence. 2011;117:66–9.

Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, Cohen P, Whiteman M. Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1039–44.

Patterson ML, Moniruzzaman A, Frankish CJ, Somers JM. Missed opportunities: childhood learning disabilities as early indicators of risk among homeless adults with mental illness in Vancouver, British Columbia. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001586.

Patterson ML, Moniruzzaman A, Somers J. Setting the stage for chronic health problems: cumulative childhood adversity among homeless adults with mental illness in Vancouver, British Columbia. BMC Pub Health. 2014;4:350.

Patterson M, Somers JM, Moniruzzaman A. Prolonged and persistent homelessness: multivariable analyses in a cohort experiencing current homelessness and mental illness in Vancouver, British Columbia. Ment Health Subst Use. 2012;5:85–101.

Palepu A, Patterson M, Strehlau V, Moniruzzaman A, Tan De Bibiana J, Frankish C, et al. Daily substance use and mental health symptoms among a cohort of homeless adults in Vancouver, British Columbia. J Urban Health. 2013;90:740–6.

Baer J, Garrett S, Beadnell B, Wells E, Peterson P. Brief motivational intervention with homeless adolescents: evaluating effects on substance use and service utilization. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:582–6.

Peterson P, Baer J, Wells E, Ginzler J, Garrett S. Short-term effects of a brief motivational intervention to reduce alcohol and drug risk among homeless adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20:254–64.

Lenz-Rashid S. Employment experiences of homeless young adults: are they different for youth with a history of foster care? Child Youth Serv Rev. 2006;28:235–59.

Whitbeck LB, Simons RL. Life on the streets: the victimization of runaway and homeless adolescents. Youth Soc. 1990;221:108–25.

Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J Adol Health. 1991;12:597–605.

Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development: A Longitudinal Study of Youth. NY: Academic Press; 1977.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Health Canada and the Mental Health Commission of Canada. The authors thank the At Home/Chez Soi Project collaborative at both national and local levels; National project team: J. Barker, PhD (2008–2011) and C. Keller, National Project Leads; P. Goering, RN, PhD, Research Lead; approximately 40 investigators from across Canada and the US; 5 site coordinators; numerous service and housing providers; and persons with lived experience.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MLP drafted the manuscript and oversaw data collection; AM conducted the statistical analyses; JMS contributed to study design and critical editing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Patterson, M.L., Moniruzzaman, A. & Somers, J.M. History of foster care among homeless adults with mental illness in Vancouver, British Columbia: a precursor to trajectories of risk. BMC Psychiatry 15, 32 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0411-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0411-3