Abstract

Background

While the association between affective disorders and sleep and circadian disturbance is well established, little is known about the neurobiology underpinning these relationships. In this study, we sought to determine the relationship between a marker of circadian rhythm and neuronal integrity (N-Acetyl Aspartate, NAA), oxidative stress (glutathione, GSH) and neuronal-glial dysfunction (Glutamate + Glutamine, Glx).

Methods

Fifty-three young adults (age range 15–33 years, mean = 21.8, sd = 4.3) with emerging affective disorders were recruited from a specialized tertiary referral service. Participants underwent clinical assessment and actigraphy monitoring, from which sleep midpoint was calculated as a marker of circadian rhythm. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy was performed in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). The metabolites NAA, GSH and Glx were obtained, and expressed as a ratio to Creatine.

Results

Neither NAA or GSH were associated with sleep midpoint. However, higher levels of ACC Glx were associated with later sleep midpoints (rho = 0.35, p = 0.013). This relationship appeared to be independent of age and depression severity.

Conclusions

This study is the first to demonstrate that delayed circadian phase is related to altered glutamatergic processes. It is aligned with animal research linking circadian rhythms with glutamatergic neurotransmission as well as clinical studies showing changes in glutamate with sleep interventions. Further studies may seek to examine the role of glutamate modulators for circadian misalignment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is well established that affective disorders are associated with sleep-wake and circadian disturbance [1]-[4]. Indeed, circadian dysfunction is postulated to play a role in the pathogenesis of mood disturbance onset, maintenance and recurrence [5]-[12]. In younger people with affective disorders, data on sleep-wake and circadian change is only beginning to emerge but suggests clear circadian misalignment early in the course of disease. Specifically, delayed sleep phase is prominent, with over 40% of young patients showing this profile [13]. In addition, advancing illness is associated with lower evening melatonin secretion, as well as short phase angles between melatonin onset and habitual sleep onset [14]. Both the unipolar and bipolar subtypes show delayed sleep and melatonin patterns, though some data indicates more pronounced phase shifts in those with bipolar disorder [4],[13].

Despite the recent advances in treatments specifically focusing on the sleep-wake system [15]-[18], our understanding of the relationship between circadian change and underlying neurobiological processes is embryonic. Indeed, even in healthy adults or adolescents there is a dearth of research specifically examining the inter-relationships between such factors. Understanding these relationships early in the course of affective disorders is relevant not only to further our scientific understanding of sleep-wake and circadian change but also to inform targeted intervention approaches [15]. Using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) we have previously reported that within the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC, a key region implicated in affective disorders), the neurometabolites N-Acetyl Aspartate (NAA; a neuronal integrity marker), glutamate (an excitatory neurotransmitter) and glutathione (GSH; a marker of oxidative stress) are likely to differ markedly across patient clusters despite their similar levels of current symptoms and functional impairments [17]. These findings are aligned with studies showing altered levels of these neurometabolites in affective disorders [19]-[22] and additionally suggest that consideration of these markers is warranted to better understand specific phenotypes, including those with prominent sleep-wake change. In this study, we sought to extend our work by examining sleep-wake and circadian functioning in relation to in-vivo measures of the brain neurometabolites NAA, GSH and glutamate + glutamine (Glx). We hypothesised that delayed sleep would be associated with decreased concentrations of NAA (indicative of neuronal compromise), GSH (indicative of oxidative stress), and increased Glx (indicative of excitatory neurotransmission).

Methods

Participants

Fifty-three young adults (age range 15–33 years, mean = 21.8, sd = 4.3) were recruited from specialised early intervention services for youth mental health (Youth Mental Health Clinic and headspace), Sydney, Australia [23]. Participants were a subset of a broader sample [17] participating in detailed neurobiological assessments. They were specifically selected for this study if their psychiatrist considered them to have an emerging affective (unipolar or bipolar) disorder [23] and they completed actigraphy monitoring and a magnetic resonance imaging scan within a one-month period. In addition to our usual exclusion criteria [17], participants undertaking shift work or having transmeridian travel within 60 days previous to data collection were excluded. Participants with an alcohol and/or substance dependence disorder were also excluded. All participants or their parents gave written informed consent prior to participation in the study. The study protocol was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee.

Procedure

Clinical assessment

As described elsewhere [23], patients were receiving care for their mental health disorder by a mental health professional and a clinical psychiatrist (namely ES, IH) confirmed affective disorder diagnoses. In addition, all participants were assessed by a trained research psychologist who recorded depression and mania symptom severity using the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) [24]. Manic symptoms were rated for a subset of 39 participants using the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) [25]. Twenty participants were taking antidepressant medications at the time of assessment which included nine taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, seven taking serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, one taking a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, one taking a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant, one taking a melatonergic antidepressant and one taking an atypical antidepressant. In addition, 11 participants were taking mood stabilising medications and 12 were taking antipsychotic medications. Thirty-two patients were classified as emerging unipolar and 21 as emerging bipolar disorder.

Sleep-wake ambulatory assessment

Participants completed sleep diary and actigraphy monitoring (Actiwatch-64/L/2, Philips Respironics, USA) for 14 days (mean duration = 12.2 days, sd = 3.3 days; median duration = 13.0 days) within one month of undergoing 1H-MRS. Actiware 5.0 software (Philips Respironics) was used to score actigraphy using a wake threshold value of medium sensitivity (40.0 activity counts/epoch). Based on sleep diaries, corrections by trained technicians were applied where necessary. Rest intervals were subsequently submitted to dual integration to define periods spent awake and resting. For the purpose of this study, actigraphic measures will be defined as ‘sleep'. The following actigraphic sleep variables were obtained for descriptive purposes: ‘sleep onset’ and ‘sleep offset’ (mean timing of the onset/offset of the rest intervals, respectively), time in bed (TiB: total duration of the rest intervals), total sleep time (TST: amount of time scored as “sleep” within the rest episode), ‘wake after sleep onset’ (WASO: amount of time scored as “wake” within the rest episode), and sleep efficiency (‘total sleep time’/‘time in bed’)*100). The primary outcome of this study was the ‘sleep midpoint’, defined as “TST/2 + sleep onset”. Sleep midpoint has been found to be the most reliable indicator of melatonin onset in young healthy participants [26] with data showing moderate to high correlations with Dim Light Melatonin Onset [27]. Thus, sleep midpoint is a useful proxy marker for circadian phase when actigraphy and sleep diaries are utilised.

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy

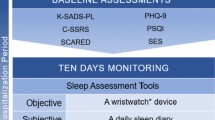

As described elsewhere [17],[28], imaging took place on a 3-Tesla GE Discovery MR750 scanner (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) using an 8-channel phased array head coil. The following images were acquired in order: (a) Three-dimensional sagittal whole-brain scout for orientation and positioning of subsequent scans; (b) T1-weighted magnetization prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence producing 196 sagittal slices to aid in the anatomical localisation of sampled voxels; and, (c) Single voxel 1H-MRS using Point RESolved Spectroscopy (PRESS) acquisition, with two chemical shift-selective imaging pulses for water suppression. Spectra were shimmed to achieve full-width half maximum of less than 13Hz. For each participant, a spectra was acquired from a voxel measuring 20×20×20 mm placed midline in the ACC (Figure 1; TE = 35 ms, TR = 2000 ms and 128 averages).

Example anterior cingulate cortex voxel placement and resulting proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy spectra for one participant. The spectra also shows Glutathione, Glutamate + Glutamine and N-Acetyl Aspartate peaks. Abbreviations are as follows: GSH = Glutathione; NAA = N-Acetyl Aspartate; Glx = Glutamate + Glutamine.

Following MRS acquisition, data was transferred offline for post processing using the LCModel software package [29] and metabolite concentrations were determined as a relative ratio to Creatine (Cr). All spectra were quantified using a PRESS TE = 35 basis set of 15 metabolites. Neurometabolites of interest were NAA, GSH and Glx. The spectra were visually inspected separately by two different raters (SD, JL) to ensure consistent spectra and poorly fitted metabolite peaks (as reflected by large Cramer–Rao lower bounds greater than 20%) were excluded from further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 20 for Mac). Student’s t-tests were used to compare group (unipolar vs. bipolar) data. Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlations were used for continuous data as appropriate. Analyses were two tailed and used an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Table 1 shows descriptive demographic, clinical, actigraphy and neurometabolite data for the sample. On average, the sample was 22 years of age with mild depressive symptoms. The mean sleep midpoint occurred at 4:14 am but ranged from 1:54 am to 7:05 am (median = 4:08 am). There were no differences between unipolar and bipolar participants in terms of age (t = −0.29, p = 0.771), gender, (x 2 = 1.52, p = 0.217) depressive symptoms (HAM-D, t = 0.86, p = 0.395), neurometabolite concentrations (Glx, t = 0.14, p = 0.173; GSH, t = 1.15, p = 0.255; NAA, t = −0.26, p = 0.797) or sleep midpoint (t = 1.1, p = 0.915). As expected, YMRS total score was significantly higher in bipolar participants (t = −2.2, p = 0.034). Importantly, there were also no significant differences between patients taking mood stabilising or antidepressant medication compared to those not taking medication at the time of assessment in terms of age, gender, depressive symptoms, mania symptoms, neurometabolite concentrations (Glx, GSH, NAA) or sleep midpoint (all p > 0.05).

The mean time of MRS collection was 3:42 pm (sd = 1.8 hrs). Correlations between 1H-MRS neurometabolites and sleep midpoint showed that neither NAA or GSH were associated with sleep midpoint (r = 0.032, p = 0.825; r = 0.211, p = 0.151 respectively). However, as shown in Figure 2, higher levels of ACC Glx were associated with later sleep midpoints (rho = 0.35, p = 0.013). In order to examine whether this association was confounded by changes in the neurobiological and/or circadian system due to the developmental process or to depressive state phenomena, we conducted further analyses controlling for age and HAM-D score. The resultant significant partial correlations showed this relationship was robust (age, r = 0.36, p = 0.012; HAM-D, r = 0.37, p = 0.009). However, when examining the relationship between ACC Glx and sleep midpoint controlling for symptoms of mania (i.e. YMRS scores, n = 39), the resulting partial correlation was not significant (partial r = 0.06, p = 0.730). This is despite the fact that YMRS scores alone were not associated with ACC Glx (r = −0.29, p = 0.862). Thus, these latter findings may be reflective of the smaller sample with YMRS scores or alternatively may suggest that manic symptoms mediate the relationship between elevated ACC Glx and later sleep midpoint.

For descriptive purposes, we secondarily examined the association between Glx and key sleep parameters. While the association with TST, TiB and sleep onset were not significant (r = −0.03, p = 0.812; r = 0.10, p = 0.457; and r = 0.24, p = 0.083 respectively), Glx was significantly associated with sleep offset (r = 0.30, p = 0.030), WASO (r = 0.325, p = 0.017), and sleep efficiency (r = −0.31, p = 0.023).

Discussion

This study is the first to demonstrate an association between in vivo neurobiological measures of brain neurometabolites and delayed sleep phase in young persons with affective disorders. Specifically, higher levels of ACC Glx, a surrogate marker of the glutamatergic system, were associated with a later sleep midpoint, suggestive of delayed circadian phase. Markers of neuronal integrity and oxidative stress were not associated with circadian phase in this sample.

In this study of youth with emerging affective disorders, we did not find any group differences in neurometabolites or sleep variables between those participants considered by the psychiatrist to have either a unipolar or bipolar illness. While the reasons for this are unclear, it is possible that they reflect the fact that the symptom severity of this sample was rather mild and encompassed those with emerging rather than full-threshold illnesses. That is, even those that were considered to have a ‘unipolar’ illness may eventually progress to bipolar disorder with longitudinal follow-up. Certainly, our data in the sub-sample of 39 participants with detailed measurement of symptoms of mania suggests that manic symptoms may contribute to the association between delayed circadian phase and Glx. Thus, it is possible that those on a trajectory to bipolar disorder are accounting for the major findings of this study, and future studies focusing on the specificity of these findings within the affective disorder sub-types is warranted.

These findings focussing on neurometabolites within the ACC are aligned with those implicating the ACC in the neurobiology of depression [30]. The ACC is densely interconnected with the hippocampus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex and hypothalamus and therefore these findings may also reflect the involvement of broader neuronal circuitry. Prior work has shown this structure to be linked to cognitive impairment and other phenotypic features in affective disorders [17],[31]. However, this study is the first to show that neurometabolite concentrations within the ACC are also relevant to sleep-wake functions. While the primary objective of this study was to examine circadian rhythm, secondary analyses also showed that higher levels of ACC Glx were related to nocturnal wakefulness and poorer sleep efficiency. Unfortunately, even in healthy samples, little is known about the inter-relationships between ACC, mood and sleep-wake functions. However, recent data from functional imaging studies show that there are diurnal changes in regional cerebral blood flow within the ACC [32], with the ACC showing a strong circadian bias in the morning. Additionally, this region is consistently implicated in insomnia (see review by Speigelhalder [33]). Further studies are now needed to further explicate how changes within the ACC circuitry may relate to circadian misalignment and nocturnal wakefulness in affective disorders.

While there is currently a dearth of studies that have examined the association between circadian and spectroscopic markers in depressive disorders, the findings of this study suggest that the glutamatergic system may be implicated in the pathogenesis of this phenotypic feature. There are certainly documented dense glutamatergic projections from the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), via the ventral subparaventricular zone and dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus, to the sleep-wake centers of the lateral hypothalamus, thereby regulating sleep-wake timing [34]. Glutamate is also a neurotransmitter of the optic nerve and retinohypothalamic tract that the SCN is sensitive to and this neurotransmitter does appear to phase shift circadian rhythms [35],[36].

With regard to the sleep system more generally, two studies have shown changes in Glx in association with sleep interventions. Specifically, Benedetti et al. [37] reported that levels of ACC Glx decrease in association with sleep deprivation, and light therapy was associated with improvements in depressive symptoms. Accordingly, Murck et al. [38] found that for males with depression, sleep deprivation is associated with an increase in Glx. The specific role that Glx substituents assume in sleep-wake cycles is currently unknown. However, it is clear that glutamate signalling is critically involved in information transmission, plasticity and neurotoxicity. Animal studies show that it increases during both waking and rapid eye movement sleep states and when the sleep period is preceded by wake states [39],[40]. Additionally, the rate of glutamate decrease is greatest with sleepiness and when slow wave activity is high [39]. Thus, it is feasible that sleep-wake history mediates glutamatergic signalling in affective disorders, though such causative relationships are yet to be demonstrated in humans.

While this study represents the first to examine the association between delayed circadian rhythms and underlying neurobiology in youth depression, several methodological factors should be considered when interpreting our findings. Firstly, the lack of a control group is a limitation of this study. This would have been particularly helpful for interpretation of these findings since it is currently unclear how sleep midpoint relates to ACC Glx in healthy adolescent or even adult samples. Secondly, adolescence itself is known to be associated with circadian delay [41]. Thus, from these results, we cannot ascertain whether our findings are reflective of adolescence generally or whether they are specific to affective disorders. Third, although the sample size of 53 is not particularly small for these types of detailed neurobiological studies, this sample is rather heterogeneous since ultimate illness trajectory is unknown in these early clinical stages [42]. Also, a larger sample would have been optimal in terms of conducting multivariable analyses whereby the influence of potential confounds could be determined concurrently. In terms of other sample characteristics, it is also important to note that details regarding female study participants’ menstrual cycle phase were not collected. Increasing evidence suggests that menstrual phase affects sleep in females [36]. However we were unable to account for the possible influence of this factor. Another consideration that could have certainly influenced circadian rhythm is psychotropic medication [43] and larger datasets would be required to analyse the contribution of antidepressant, mood stabilising or anti-psychotic medication.

Regarding the spectroscopy component of the study, it is important to note that since we examined Glx as a surrogate marker of glutamate, the current findings may in part be reflective of glutamine. Further research examining the roles of Glu and glutamine are now required to further delineate their role in sleep-wake function in both healthy and psychiatric samples. Furthermore, this study used a PRESS sequence to examine GSH concentration. Although we have previously validated the GSH signal measured using this sequence, replication of null findings using MEGA-PRESS may be warranted. In this study, MRS measures were derived across various times of the day, and if in-vivo measures of brain neurometabolites also vary according to circadian rhythm, this is a potential source of noise that could be eradicated if scanning were to occur at a fixed time period. Finally, due to the inability to conduct spectroscopy within the SCN or its neighbouring hypothalamic sleep-wake centres, we were of course unable to measure Glx within these regions. Thus, we cannot be confident that ACC Glx sufficiently captures glutamatergic concentration within regions critical for the circadian regulation of sleep.

In terms of sleep and circadian assessment, this study used actigraphy to derive sleep midpoint, but polysomnography studies may yield a more accurate determination of this measure and future investigations should incorporate melatonin and other endogenous circadian markers.

Conclusions

Overall, this study is the first to demonstrate a link between markers of the glutamatergic system in affective disorders and delayed sleep-wake cycle. It enhances our prior work examining delayed sleep and melatonin in affective disorders [4],[13],[14] by specifically linking this key phenotypic feature to a neurobiological marker implicated in affective disorders, and provides an impetus for further exploratory work in this area. Our results further suggest that this association might be particularly influenced by symptoms of mania. While not the focus of this study, we also found that ACC Glx was associated with poorer sleep, as evidenced by more nocturnal awakenings and poorer sleep efficiency.

Whilst these findings are preliminary and require replication in larger samples, they have potential significance for the clinical management of young people with emerging affective disorders. In particular, given the increasing recognition of the role of glutamate in affective disorders, it is possible that glutamatergic modulators might help to restore circadian misalignment, which in turn, could prevent affective symptom onset, severity and recurrence [15].

Abbreviations

- 1H-MRS:

-

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- ACC:

-

Anterior cingulate cortex

- Cr:

-

Creatine

- Glx:

-

Glutamate + Glutamine

- GSH:

-

Glutathione

- HAM-D:

-

Hamilton depression rating scale

- NAA:

-

N-Acetyl Aspartate

- SCN:

-

Suprachiasmatic nucleus

- TiB:

-

Time in Bed

- TST:

-

Total sleep time

- WASO:

-

Wake after sleep onset

References

Lewy AJ: Circadian misalignment in mood disturbances. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009, 11 (6): 459-465. 10.1007/s11920-009-0070-5.

Tsuno N, Besset A, Ritchie K: Sleep and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005, 66 (10): 1254-1269. 10.4088/JCP.v66n1008.

Boivin DB: Influence of sleep-wake and circadian rhythm disturbances in psychiatric disorders. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2000, 25 (5): 446-458.

Robillard R, Naismith SL, Rogers NL, Scott EM, Ip TKC, Hermens DF, Hickie IB: Sleep-wake cycle and melatonin rhythms in adolescents and young adults with mood disorders: comparison of unipolar and bipolar phenotypes. Eur Psychiatry. 2013, 28 (7): 412-416. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.04.001.

Germain A, Kupfer DJ: Circadian rhythm disturbances in depression. Hum Psychopharm Clin Exp. 2008, 23 (7): 571-585. 10.1002/hup.964.

Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, Levin MJ, Oxman MN, Irwin MR: Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008, 165 (12): 1543-1550. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121882.

Srinivasan V, Pandi-Perumal SR, Trakht I, Spence DW, Hardeland R, Poeggelerd B, Cardinali DP: Pathophysiology of depression: role of sleep and the melatonergic system. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 165 (3): 201-214. 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.11.020.

Boivin DB, Czeisler CA, Dijk DJ, Duffy JF, Folkard S, Minors DS, Totterdell P, Waterhouse JM: Complex interaction of the sleep-wake cycle and circadian phase modulates mood in healthy subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997, 54 (2): 145-152. 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830140055010.

Mendlowicz MV, Jean-Louis G, von Gizycki H, Zizi F, Nunes J: Actigraphic predictors of depressed mood in a cohort of non-psychiatric adults. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999, 33 (4): 553-558. 10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.00585.x.

Sadeh A, Mcguire JPD, Sacks H, Seifer R, Tremblay A, Civita R, Hayden RM: Sleep and psychological characteristics of children on a psychiatric inpatient unit. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995, 34 (6): 813-819. 10.1097/00004583-199506000-00023.

Wirz-Justice A, Van den Hoofdakker RH: Sleep deprivation in depression: What do we know, where do we go?. Biol Psychiatry. 1999, 46 (4): 445-453. 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00125-0.

Borbély AA, Wirz-Justice A: Sleep, sleep deprivation and depression: a hypothesis derived from a model of sleep regulation. Hum Neurobiol. 1982, 1 (3): 205-210.

Robillard R, Naismith SL, Rogers NL, Ip TKC, Hermens DF, Scott EM, Hickie IB: Delayed sleep phase in young people with unipolar or bipolar affective disorders. J Affect Disord. 2013, 145 (2): 260-263. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.006.

Naismith SL, Hermens DF, Ip TKC, Bolitho S, Scott E, Rogers NL, Hickie IB: Circadian profiles in young people during the early stages of affective disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2012, 2 (5): e123-10.1038/tp.2012.47.

Hickie IB, Rogers NL: Novel melatonin-based therapies: potential advances in the treatment of major depression. Lancet. 2011, 378 (9791): 621-631. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60095-0.

Hickie IB, Naismith SL, Robillard R, Scott EM, Hermens DF: Manipulating the sleep-wake cycle and circadian rhythms to improve clinical management of major depression. BMC Med. 2013, 11: 79-10.1186/1741-7015-11-79.

Hermens DF, Lagopoulos J, Naismith SL, Tobias-Webb J, Hickie IB: Distinct neurometabolic profiles are evident in the anterior cingulate of young people with major psychiatric disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2012, 2 (5): e10-10.1038/tp.2012.35.

Wirz-Justice A: Chronobiology and psychiatry. Sleep Med Rev. 2007, 11 (6): 423-427. 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.08.003.

Caetano SC, Olvera RL, Hatch JP, Sanches M, Chen HH, Nicoletti M, Stanley JA, Fonseca M, Hunter K, Lafer B, Pliszka SR, Soares JC: Lower N-acetyl-aspartate levels in prefrontal cortices in pediatric bipolar disorder: A H-1 magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011, 50 (1): 85-94. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.007.

Yildiz-Yesiloglu A, Ankerst DP: Neurochemical alterations of the brain in bipolar disorder and their implications for pathophysiology: a systematic review of the in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy findings. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006, 30 (6): 969-995. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.03.012.

Portella MJ, de Diego-Adelino J, Gomez-Anson B, Morgan-Ferrando R, Vives Y, Puigdemont D, Perez-Egea R, Ruscalleda J, Alvarez E, Perez V: Ventromedial prefrontal spectroscopic abnormalities over the course of depression: a comparison among first episode, remitted recurrent and chronic patients. J Psychiatric Res. 2011, 45 (4): 427-434. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.08.010.

Yuksel C, Ongur D: Magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies of glutamate-related abnormalities in mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2010, 68 (9): 785-794. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.016.

Hickie IB, Scott EM, Hermens DF, Naismith SL, Guastella AJ, Kaur M, Sidis A, Whitwell B, Glozier N, Davenport T, Pantelis C, Wood SJ, McGorry PD: Applying clinical staging to young people who present for mental health care. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2013, 7 (1): 31-43. 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2012.00366.x.

Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960, 23: 56-62. 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56.

Young R, Biggs J, Ziegler V, Meyer D: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978, 133 (5): 429-435. 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429.

Martin SK, Eastman CI: Sleep logs of young adults with self-selected sleep times predict the dim light melatonin onset. Chronobiol Int. 2002, 19 (4): 695-707. 10.1081/CBI-120006080.

Burgess HJ, Savic N, Sletten T, Roach G, Gilbert SS, Dawson D: The relationship between the dim light melatonin onset and sleep on a regular schedule in young healthy adults. Behav Sleep Med. 2003, 1 (2): 102-114. 10.1207/S15402010BSM0102_3.

Duffy SL, Lagopoulos J, Hickie IB, Diamond K, Graeber MB, Lewis SJ, Naismith SL: Glutathione relates to neuropsychological functioning in mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2014, 10 (1): 67-75. 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.005.

Provencher SW: Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in-vivo proton nmr-spectra. Magn Reson Med. 1993, 30 (6): 672-679. 10.1002/mrm.1910300604.

Naismith S, Norrie L, Mowszowski L, Hickie I: The neurobiology of depression in later-life: clinical, neuropsychological, neuroimaging and pathophysiological features. Prog Neurobiol. 2012, 98: 99-143. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.05.009.

Rodríguez-Cano E, Sarró S, Monté G, Maristany T, Salvador R, McKenna P, Pomarol-Clotet E: Evidence for structural and functional abnormality in the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in major depressive disorder. Psychol Med. 2014, 44 (15): 3263-3273. 10.1017/S0033291714000841.

Hodkinson DJ, O'Daly O, Zunszain PA, Pariante CM, Lazurenko V, Zelaya FO, Howard MA, Williams SC: Circadian and homeostatic modulation of functional connectivity and regional cerebral blood flow in humans under normal entrained conditions. J Cereb Blood Flow Metabol. 2014, 34 (9): 1493-1499. 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.109.

Spiegelhalder K, Regen W, Nanovska S, Baglioni C, Riemann D: Comorbid sleep disorders in neuropsychiatric disorders across the life cycle. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013, 15 (6): 1-6. 10.1007/s11920-013-0364-5.

Fuller PM, Gooley JJ, Saper CB: Neurobiology of the sleep-wake cycle: sleep architecture, circadian regulation, and regulatory feedback. J Biol Rhythms. 2006, 21 (6): 482-493. 10.1177/0748730406294627.

Hamada T, Sonoda R, Watanabe A, Ono M, Shibata S, Watanabe S: NMDA induced glutamate release front the suprachiasmatic nucleus: an in vitro study in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1998, 256 (2): 93-96. 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00762-9.

Meijer JH, Vanderzee EA, Dietz M: Glutamate phase-shifts circadian activity rhythms in hamsters. Neurosci Lett. 1988, 86 (2): 177-183. 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90567-8.

Benedetti F, Calabrese G, Bernasconi A, Cadioli M, Colombo C, Dallaspezia S, Falini A, Radaelli D, Scotti G, Smeraldi E: Spectroscopic correlates of antidepressant response to sleep deprivation and light therapy: a 3.0 Tesla study of bipolar depression. Psych Res Neuroimaging. 2009, 173 (3): 238-242. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.08.004.

Murck H, Schubert MI, Schmid D, Schuessler P, Steiger A, Auer DP: The glutamatergic system and its relation to the clinical effect of therapeutic-sleep deprivation in depression - an MR spectroscopy study. J Psychiatric Res. 2008, 43 (3): 175-180. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.04.009.

Dash MB, Douglas CL, Vyazovskiy VV, Cirelli C, Tononi G: Long-term homeostasis of extracellular glutamate in the rat cerebral cortex across sleep and waking states. J Neurosci. 2009, 29 (3): 580-589. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5486-08.2009.

Lopez-Rodriguez F, Medina-Ceja L, Wilson CL, Jhung D, Morales-Villagran A: Changes in extracellular glutamate levels in rat orbitofrontal cortex during sleep and wakefulness. Arch Med Res. 2007, 38 (1): 52-55. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2006.07.004.

de Souza CM, Hidalgo MPL: Midpoint of sleep on school days is associated with depression among adolescents. Chronobiol Int. 2014, 31 (2): 199-205. 10.3109/07420528.2013.838575.

Carvalho LA, Gorenstein C, Moreno R, Pariante C, Markus RP: Effect of antidepressants on melatonin metabolite in depressed patients. J Psychopharmacol. 2009, 23 (3): 315-321. 10.1177/0269881108089871.

Martin J, Jeste DV, Caliguiri MP, Patterson T, Heaton R, Ancoli-Israel S: Actigraphic estimates of circadian rhythms and sleep/wake in older schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2001, 47 (1): 77-86. 10.1016/S0920-9964(00)00029-3.

Acknowledgments

Prof Naismith is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Award. Prof Hickie is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Fellowship. Mr White is supported by ‘Optymise’, an NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence. Dr Duffy is supported by a fellowship from ‘Neurosleep’, an NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence. Dr Robillard is supported by a postdoctoral training award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Prof Naismith, A/Prof Lagopoulos, Dr Hermens, Mr White, Dr Duffy, Dr Robillard and Dr Scott have no competing interests to declare. Prof Hickie was a director of headspace: the national youth mental health foundation until January 2012. He is the executive director of the Brain and Mind Research Institute, which operates two early-intervention youth services under contract to headspace. He is a member of the new Australian National Mental Health commission and was previously the CEO of beyondblue: the national depression initiative. Prof Hickie has led a range of community-based and pharmaceutical industry-supported depression awareness and education and training programs. He has also led depression and other mental health research projects that have been supported by a variety of pharmaceutical partners. Current investigator-initiated studies are supported by Servier and Pfizer. He has received honoraria for his contributions to professional educational seminars supported by the pharmaceutical industry (including Servier, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Eli Lilly).

Authors’ contributions

SN participated in the design of the study, carried out the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript and revisions. JL carried out the spectroscopy analysis and provided input regarding interpretation of results. DH oversaw study implementation and assisted with data collection. DW, SD and RR assisted with data collection and analysis. IH and ES conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Naismith, S.L., Lagopoulos, J., Hermens, D.F. et al. Delayed circadian phase is linked to glutamatergic functions in young people with affective disorders: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. BMC Psychiatry 14, 345 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0345-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0345-1