Abstract

Background

Button battery (BB) ingestions (BBI) are increasingly prevalent in children and constitute a significant, potentially life-threatening health hazard, and thus a pediatric emergency. Ingested BBs are usually charged and can cause severe symptom within 2 h. Discharged BBs ingestion is very rare and protracted symptom trajectories complicate diagnosis. Timely imaging is all the more important. Discharged BBs pose specific hazards, such as impaction, and necessitate additional interventions.

Case presentation

We present the case of a previously healthy 19-month-old girl who was admitted to our pediatric university clinic in Germany for assessment of a three-month history of intermittent, mainly inspiratory stridor, snoring and feeding problems (swallowing, crying at the sight of food). The child’s physical examination and vital signs were normal. Common infectious causes, such as bronchitis, were ruled out by normal lab results including normal infection parameters, negative serology for common respiratory viruses, and normal blood gas analysis, the absence of fever or pathological auscultation findings. The patient’s history contained no evidence of an ingestion or aspiration event, no other red flags (e.g., traveling, contact to TBC). Considering this and with bronchoscopy being the gold standard for foreign body (FB) detection, an x-ray was initially deferred. A diagnostic bronchoscopy, performed to check for airway pathologies, revealed normal mucosal and anatomic findings, but a non-pulsatile bulge in the trachea. Subsequent esophagoscopy showed an undefined FB, lodged in the upper third of the otherwise intact esophagus. The FB was identified as a BB by a chest X-ray. Retrieval of the battery proved extremely difficult due to its wedged position and prolonged ingestion and required a two-stage procedure with consultation of Ear Nose Throat colleagues. Recurring stenosis and regurgitation required one-time esophageal bougienage during follow-up examinations. Since then, the child has been asymptomatic in the biannual endoscopic controls and is thriving satisfactorily.

Conclusion

This case describes the rare and unusual case of a long-term ingested, discharged BB. It underscores the need for heightened vigilance among healthcare providers regarding the potential hazards posed by discharged BBIs in otherwise healthy children with newly, unexplained stridor and feeding problems. This case emphasizes the critical role of early diagnostic imaging and interdisciplinary interventions in ensuring timely management and preventing long-term complications associated even to discharged BBs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Button battery (BB) ingestions (BBI) are increasingly prevalent in children [1, 2]. This constitutes a significant, potentially life-threatening health hazard as the electrical current from ingested charged BBs can result in severe burns to the surrounding tissue. This may lead to complications such as vocal cord injuries, aero-digestive mucosal lesions, mediastinitis, strictures, perforations, pneumothoraces, spondylodiscitis, trachea-esophageal or aorto-esophageal fistulas, and life-threatening hemorrhages. 3 V Lithium BBs with a 20 mm diameter account for the majority of severe or fatal outcomes [3,4,5]. Consequently, BBI constitutes a pediatric emergency [1, 3, 4, 6] and requires urgent removal. Mucosal injury can occur two hours after ingestion, and perforation around twelve hours [3, 4, 6]. Ingested foreign bodies (FB) commonly lodge in the esophagus, especially at the thoracic inlet, aortic arch region, and gastroesophageal junction. This causes symptoms such as retching, vomiting, dysphagia, salivation, and regurgitation. In undetected ingestions, symptoms may be nonspecific, e.g. restlessness, fever, and failure to thrive [1, 7]. This particularly concerns younger children, often leading to delayed or false diagnosis [1, 5].

Ingested BBs are usually charged, making a fast manifestation likely due to the severe, rapid symptom onset. This case report focusses on the rare event of ingestion of discharged BBs. Since discharged BBIs are extremely rare, they do not match the usual diagnostic algorithms routinely used by physicians. This report highlights the diagnostic challenges, namely unspecific, protracted symptom trajectories, and risk of impaction over time and illustrates the hazards associated even with discharged BBs. It concludes that if detection and removal is delayed, additional interventions may be necessary to address complications, such as surgical procedures or repeated esophagoscopic dilatation to treat strictures. Our case report aims to emphasize the need for heightened suspicion and vigilance of discharged BB in children with unexplained chronic stridor as well as early consideration of diagnostic imaging and interdisciplinary management.

Case presentation

We present the case of a 19-month-old girl who was assigned to our clinic for further investigation of unspecific pulmonary symptoms, stridor and poor feeding – quickly unfolding as the unusual case of a 3-months-old ingestion of a discharged, now impacted BB.

The child was referred to our pediatric gastroenterology clinic by her resident pediatrician for further symptom assessment. The patient’s history had started three months earlier with symptoms of a mild respiratory infection (Table 1). Fever, cough, and rhinitis occurred occasionally thereafter. Several weeks later, mild problems developed concerning swallowing and an inspiratory stridor when crying. Food intake, especially solids, was also reduced during infection-free intervals. Crying attacks occurred when eating or even seeing food.

One month after symptom onset, the child visited her resident pediatrician for a routine check-up. The doctor observed the stridor and prescribed inhalation therapy with Salbutamol. Additionally, he referred the child to an outpatient ear nose and throat (ENT) specialist. The ENT examination, a few weeks later, showed no nasopharyngeal or oral abnormalities. However, the larynx could not be examined, and the ENT referred the child to an ENT hospital clinic for further assessment. There, an endoscopy up to the epiglottis revealed no suspicious findings. Continuation of inhalation therapy with sympathomimetics and cortisone suppositories as well as a diagnostic bronchoscopy was recommended.

For this, the girl was taken to our clinic. She presented mildly agitated, in good health, with a weight of 9.75 kg (15. percentile), and height of 79.6 cm (15. percentile). Physical examination revealed normal lung auscultation with bilaterally equal vesicular breathing sounds, inspiratory stridor when crying, and otherwise normal findings. SpO2 was 98% and body temperature 37.4 °C, remaining vital signs were normal. Further anamnesis revealed no chronic infections or diseases, no allergies, no previous surgeries, or intubations, no known genetic disorders. Her motor, psycho-social and speech development was age-appropriate. Labs (blood count, liver, kidney, inflammation parameters, coagulation) showed mild leucocytosis, anemia, and thrombocytosis, but negative infection markers. She snored whilst sleeping, but SpO2 levels remained stable.

The child’s medical history was empty for aspiration or ingestion of FB or dangerous liquids, or other red flags. Given the child’s age, laryngo- or tracheomalacia was unlikely. Other differential diagnoses included newly developed stenosis, e.g., due to hemangioma, or neoplasm, which warranted a diagnostic bronchoscopy. In the pre-existing records from the outpatient setting, there was no indication that imaging (X-ray) was considered, and there was a greater expectation of diagnostic value performing an elective bronchoscopy to clarify the patient's symptoms.

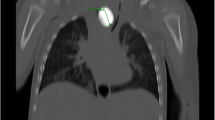

The intervention was conducted on the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) in the PICU’s dedicated endoscopy room by a multiprofessional team consisting of specialists from pediatric and adult endoscopy, pediatric intensive care, pediatric surgery, and pediatric anesthesia. All team members had extensive training and experience in the procedure. Bronchoscopy showed an overall normal bronchial structure except for a non-pulsatile stenosis in the middle of the trachea (Fig. 1), prompting a diagnostic esophagoscopy directly afterwards.

This revealed an undefined, metallic FB lodged in the upper third of the esophagus (Fig. 2). The FB resembled a BB, however, due to the long impaction time, this seemed unlikely. For clarification, we conducted a chest X-ray. This identified a BB above the proximal esophageal junction (Fig. 3). To secure the airway, the child was then nasally intubated.

Directly afterwards, we attempted a flexible endoscopic retrieval, using grasping forceps, snares and traps. As this proved unsuccessful, we switched to rigid bronchoscopy, laryngoscope and Magill forceps. Anatomic structures further complicated wedging and made salvage extremely difficult. Due to increasing edematous swelling of the area, further attempts were terminated after several hours, and the intubated and sedated child remained in a patient room at our PICU. On the same day, the ENT department was consulted to perform a rigid esophagoscopy the next day after swelling declined.

The following day, the ENT team (consisting only of consultants with year-long experience) conducted the procedure in theater. For this, the child was put under general anesthesia. The battery was fixated with large grasping forceps. Extraction remained challenging, required considerable force, but eventually proved successful. After retrieval of a type 2032 BB, a gastric tube was left in place to splint the esophagus. The patient remained stable at all times and was transferred back to our PICU for ventilation and monitoring. Post-operative care included intravenous antibiotics to prevent mediastinitis (Cefuroxime 150 mg/kgKG bw/d, Metronidazole 30 mg/kg bw/d, Gentamicin 5 mg/kgKG bw/d), fresh frozen plasma due to mildly abnormal coagulation parameters and regarding the extensive esophageal manipulation, and enteral feeding through a gastric tube to allow the esophageal mucosa to heal.

Five days post intervention, an esophageal fluoroscopy revealed no signs of perforation, and the patient was extubated. Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered for two more days (in total 7 days). Inflammation markers (CRP) peaked at 44.8 mg/l on the day of FB extraction and decreased rapidly. Seven days after removal, a stepwise oral reinduction of liquids was commenced. Eleven days post intervention, a control endoscopy showed a circumscribed, fibrin-covered incipient scarring erosion, but no evidence of ulceration, pocket formation, or stenosis. Solids were gradually reintroduced and eating and drinking behavior remained complication-free. After feeding tube removal on day 14, the girl was discharged the following day.

A detailed review of the disease trajectory and reevaluation with the mother revealed that an unobserved sudden coughing attack without cyanosis had occurred in the context of a respiratory infection three months prior to presenting to our clinic. It is possible that this constituted the unobserved BBI.

Follow-up care

Two months later, a follow-up revealed no stridor, but regurgitation happened occasionally, especially with solids. Esophagoscopy showed a narrowing of 10 mm in diameter at 10 cm from the dental arch, and a lateral pocket formation above (Fig. 4), prompting bougienage with dilators up to 13 mm. Afterwards, gradual reintroduction of food was complication-free. Another control endoscopy 6 weeks later showed a 10 mm stenosis and a persistent pocket. Since the child had been asymptomatic, no bougienage was performed this time. The following control endoscopy another 6 weeks later revealed a persistent but short-segment stenosis. The pocket remained unchanged. It is assumed that the pocket will stretch with growth. The latest follow-up examinations also point in this direction. Unlike larger pockets, food residue accumulation is not a concern in this instance. Currently, endoscopic controls are performed biannually as the patient remains asymptomatic and is thriving according to age. No bougienage has been performed since. If the situation remains stable, the monitoring intervals will be extended. Overall, the follow-up has been and continues to be uncomplicated, challenges occurred at no time and the family and patient were compliant and attended the appointments reliably at all times.

Patient perspective

The parents reported a positive relationship with the healthcare team, characterized by effective and transparent communication at eye level at all times both during the acute treatment of the BBI as well as during the follow up visits. They expressed satisfaction with the empathetic, collaborative and constructive approach aimed at the child's welfare.

Discussion

FB ingestions constitutes a common problem in pediatrics, with BBIs making up 5%–11% [8,9,10,11] of all FB ingestions. Toddlers ≤ 6 years [1, 3, 12, 13] are at the highest risk for BBIs, accounting for 57–80% of cases, incidence rates in older children are lower [12,13,14]. BBIs have complication rates between 0.166%–12.6% [3, 15], and a lethality of 0.04% [15]. Due to initially vague symptoms, diagnosis is often delayed [3, 16]. In our case, in hindsight, all the child's symptoms can be attributed to the esophageal BB obstruction. Retrospectively, the nocturnal breathing noises described as snoring – normally caused by upper airway obstruction – are more likely to be due to an obstruction of the lower airways caused by the protruding BB in the esophagus. Nevertheless, initially, BBI seemed very unlikely due to the atypical, prolonged trajectory and anamnesis unindicative of FB. Unspecific symptoms and newly developed stridor justified a diagnostic bronchoscopy, especially as bronchoscopy constitutes the most sensitive and accurate method for diagnosing FBs [17, 18]. Radiographs do not often offer additional insight for acute stridor [19], and its benefit is equivocal, especially in radiolucent FBs [18, 20]. However, in chronic cases like this, a prior chest x-ray would have been warranted [20, 21].

It remains unclear to what extent anatomical features of the lodged position impeded recovery. The proximal portion of the esophagus, where the BB was lodged, is built from striated muscle. This together with the complex neuronal innervation in this region may have influenced the clinical outcome and the difficult extraction of the BB. Since endoscopy showed no signs of ulceration in our case, mucosal destruction, or fistulation, the BB must have been discharged upon ingestion. While BBIs are common, prolonged courses without detrimental consequences are very rare. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of refractory chronic stridor due to unwitnessed, prolonged BBI. Two reports describe cases of toddlers with a 3-months history of swallowing difficulties after unwitnessed BBI [22, 23]. Contrary to our case, they developed no consequences such as strictures after removal. Alam et al. report the case of a 2-year-old child with swallowing difficulties over 7 months, eventually diagnosed as BBI. The boy survived but required thoracotomy for removal [24]. Several publications of prolonged BBI report fatalities due to trachea-esophageal fistulation or sudden hemorrhage after vasculo-esophageal fistulation [3, 25,26,27,28].

Relevant points can be learnt: Firstly, in children < 6 years with prolonged respiratory symptoms or feeding problems, FB ingestion or aspiration needs to be considered. Secondly, while extended asymptomatic BBI is rare, its consideration is important given the prevalence of BBI in toddlers. Aligning with this, in cases of unclear, chronic stridor, a chest x-ray is warranted. Furthermore, in cases of ambiguous symptoms, or new respiratory/feeding issues, a thorough anamnesis is essential. This should include asking about (i) the presence of BBs at home, and (ii) signs of FB aspiration/ingestion. Thirdly, in complex FB infestation, early consultation with ENT specialists is recommended for their expertise with additional instruments like rigid esophagoscopy. This should occur across hospital boundaries, as children may need to be transferred or specialized equipment brought into the clinics. Lastly, but nevertheless urgently, the frequency and severity of BBIs warrant greater industry efforts to mitigate risks. Preventive approaches already exist (e.g., safer packaging and battery design, special coating) [2, 7, 29]. However, prevention is always better than treatment, especially in cases of foreign body ingestion in a vulnerable group such as toddlers. Thus, stricter product standards, legal [30] and governmental regulations and heightened public awareness are strongly recommended.

Conclusion

Unwitnessed BBIs in children presents a diagnostic challenge. Although life-threatening hazards such as ulceration and perforation are unlikely in discharged BBs, they still pose a significant risk, and may lead to long-term complications as observed here. BBI should be considered in children with newly developed airway and feeding problems. An early chest x-ray is warranted in pediatric stridor of unknown origin. Children with prolonged BBI are at risk of a complexly lodged FB, and highly benefit from an interdisciplinary endoscopic salvage approach.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data is included in the case report. Further information are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BB:

-

Button battery

- BBI:

-

Button battery ingestion

- ENT:

-

Ear, nose and throat

- FB:

-

Foreign body

- PICU:

-

Pediatric intensive care unit

References

Eliason MJ, Melzer JM, Winters JR, Gallagher TQ. Identifying predictive factors for long-term complications following button battery impactions: a case series and literature review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;87:198–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.06.016.

Jatana KR, Litovitz T, Reilly JS, Koltai PJ, Rider G, Jacobs IN. Pediatric button battery injuries: 2013 task force update. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77(9):1392–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.06.006.

Litovitz T, Whitaker N, Clark L, White NC, Marsolek M. Emerging battery-ingestion hazard: clinical implications. Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):1168–77. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3037.

Soto PH, Reid NE, Litovitz TL. Time to perforation for button batteries lodged in the esophagus. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(5):805–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.07.035.

Shaffer AD, Jacobs IN, Derkay CS, et al. Management and outcomes of button batteries in the aerodigestive tract: a multi‐institutional study. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(1):E298. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28568.

Al Lawati TT, Al Marhoobi RM. Timing of button battery removal from the upper gastrointestinal system in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(8):e461–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001697.

Sethia R, Gibbs H, Jacobs IN, Reilly JS, Rhoades K, Jatana KR. Current management of button battery injuries. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2021;6(3):549–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.535.

Orsagh-Yentis D, McAdams RJ, Roberts KJ, McKenzie LB. Foreign-body ingestions of young children treated in US emergency departments: 1995–2015. Pediatrics. 2019;143(5):e20181988. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-1988.

Khorana J, Tantivit Y, Phiuphong C, Pattapong S, Siripan S. Foreign body ingestion in pediatrics: distribution, management and complications. Medicina. 2019;55(10):686. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55100686.

Speidel AJ, Wölfle L, Mayer B, Posovszky C. Increase in foreign body and harmful substance ingestion and associated complications in children: a retrospective study of 1199 cases from 2005 to 2017. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):560. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02444-8.

Xu G, Chen YC, Chen J, Jia DS, Wu ZB, Li L. Management of oesophageal foreign bodies in children: a 10-year retrospective analysis from a tertiary care center. BMC Emerg Med. 2022;22(1):166. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-022-00723-4.

Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MC, et al. 2021 annual report of the National Poison Data System© (NPDS) from America’s poison centers: 39th annual report. Clin Toxicol. 2022;60(12):1381–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2022.2132768.

Chandler MD, Ilyas K, Jatana KR, Smith GA, McKenzie LB, MacKay JM. Pediatric battery-related emergency department visits in the United States: 2010–2019. Pediatrics. 2022;150(3):e2022056709. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-056709.

Gatto A, Capossela L, Ferretti S, et al. Foreign body ingestion in children: epidemiological, clinical features and outcome in a third level emergency department. Children. 2021;8(12):1182. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8121182.

Varga Á, Kovács T, Saxena AK. Analysis of complications after button battery ingestion in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34(6):443–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001413.

Chessman R, Verkerk M, Hewitt R, Eze N. Delayed presentation of button battery ingestion: a devastating complication. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2017-219331.

Divisi D, Di Tommaso S, Garramone M, Di Francescantonio W, Crisci RM, Costa AM, Gravina GL, Crisci R. Foreign bodies aspirated in children: role of bronchoscopy. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;55(4):249–52. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-924714.

Hitter A, Hullo E, Durand C, Righini CA. Diagnostic value of various investigations in children with suspected foreign body aspiration: review. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011;128(5):248–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2010.12.011.

Goodman TR, McHugh K. The role of radiology in the evaluation of stridor. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81(5):456–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.81.5.456.

Wissenschaftlicher Arbeitskreis Kinderanästhesie (WAKKA) der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anästhesiologie und Intensivmedizin (DGAI), Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Pneumologie (GPP), Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Pneumologie (SGPP), Arbeitsgemeinschaft Pädiatrische HNO-Heilkunde (AG PädHNO) der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Hals-Nasen-Ohren-Heilkunde, Kopf-Hals-Chirurgie (DG HNO KCH), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinderchirurgie (DGKCH), Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Gastroenterologie und Ernährung (GPGE) , Gesellschaft für Neonatologie und Pädiatrische Intensivmedizin (GNPI). Interdisziplinäre Versorgung von Kindern nach Fremdkörperaspiration und Fremdkörperingestion. AWMF S2k-Guideline Fremdkörper Kinder. 2015. AMWF Guideline-register Nr. 001/031. Online: https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/001-031l_S2k_Fremdkörperversorgung_Kinder_2016-01-abgelaufen_01.pdf . Access: 01.02.2024.

Rose D, Dubensky L. Airway foreign bodies. [Updated 2023 Aug 7]. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539756/. Access: 01.02.2024.

Marshalla J. Prolonged esophageal button battery impaction in a 15 month-old: a case report. J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2016;2(3):044. https://doi.org/10.23937/2469-5793/1510044.

Gohil R, Culshaw J, Jackson P, Singh S. Accidental button battery ingestion presenting as croup. J Laryngol Otol. 2014;128(3):292–5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215114000073.

Alam E, Mourad M, Akel S, Hadi U. A case of battery ingestion in a pediatric patient: what is its importance? Case Rep Pediatr. 2015;2015:345050. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/345050.

Janarthanan V, Moorthi K, Shaha KK. Fatality due to button battery lodgment in the upper digestive tract of a neonate: an unusual presentation. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2019;40(3):298. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAF.0000000000000495.

Karnecki K, Pieśniak D, Jankowski Z, Gos T, Kaliszan M. Fatal haemorrhage from an aortoesophageal fistula secondary to button battery ingestion in a 15-month-old child. Case report and literature review. Leg Med. 2020;45:101707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2020.101707.

Guinet T, Gaulier JM, Moesch C, Bagur J, Malicier D, Maujean G. Sudden death following accidental ingestion of a button battery by a 17-month-old child: a case study. Int J Legal Med. 2016;130(5):1291–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-016-1329-0.

Mercer RW, Schwartz MC, Stephany J, Donnelly LF, Franciosi JP, Epelman M. Vascular ring complicates accidental button battery ingestion. Clin Imaging. 2015;39(3):510–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2015.01.009.

Laulicht B, Traverso G, Deshpande V, Langer R, Karp JM. Simple battery armor to protect against gastrointestinal injury from accidental ingestion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(46):16490–5. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1418423111.

Paull J. Infant Button Battery Injury and Death (IBBID): legal remedies and options for redress. Eur J Law Pol Sci. 2023;2(4):34–8. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejpolitics.2023.2.4.105.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient and her parents for permitting us to present the case and data.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DM and JM were involved in the patient care, helped with collecting case information and drafting the initial manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript. EH helped with drafting the manuscript and interpreting findings, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. ZSO conceptualized the case presentation, drafted the manuscript, carried out the finalization of the manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. SG was directly involved in the diagnostic process, conceptualized the case presentation, drafted the manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent to anonymously publish this case report has been obtained from the child’s parents.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Oftring, Z.S., Mehrtens, D.M., Mollin, J. et al. Chronic stridor in a toddler after ingestion of a discharged button battery: a case report. BMC Pediatr 24, 246 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-04730-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-04730-1