Abstract

Background

Suboptimal child nutrition remains the main factor underlying child undernutrition in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This study aimed to assess the prevalence of minimum acceptable diet and associated factors among children aged 6–23 months old.

Methods

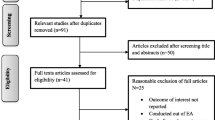

Community-based cross-sectional study including 742 mothers with children aged 6–23 months old was conducted in 2 Health Zones of South Kivu, Eastern DRC. WHO indicators of Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) regarding complementary feeding practices were used. Logistic regression analysis was used to quantify the association between sociodemographic indicators and adequate minimum acceptable diet for both univariate and multivariate analysis.

Results

Overall, 33% of infants had minimum acceptable diet. After controlling for a wide range of covariates, residence urban area (AOR 2.39; 95% CI 1.43, 3.85), attendance postnatal care (AOR 1.68; 95% CI 1.12, 2.97), education status of mother (AOR 1.83; 95% CI 1.20, 2.77) and household socioeconomic status (AOR 1.72; 95% CI 1.14, 2.59) were factors positively associated with minimum acceptable diet.

Conclusion

Actions targeting these factors are expected to improve infant feeding practices in South Kivu.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 2 and 3 call for an ending all forms of undernutrition, and all preventable deaths under 5 years of age by 2030 [1]. Worldwide, 5.4 million children under-five still die each year, 80% of them in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Almost half of these deaths occur among undernourished children [2, 3]. Although these deaths are the result of a complex set of determinants, poor breastfeeding practices and inadequate complementary feeding play a major role [4]. Therefore, optimal infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices rank among the most effective interventions to improve child health.

In 2002, the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) adopted the global strategy for IYCF, including: (i) early initiation of breastfeeding within 1 h of birth; (ii) exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life and (iii) introduction of nutritionally-adequate and safe complementary (solid) foods at 6 months together with continued breastfeeding up to 2 years of age or beyond [5].

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is still recovering from years of war and political upheaval and continues to face significant humanitarian challenges. Since 2016, the long-running crisis in Eastern regions has forced some 4.8 million internally displaced persons to flee from their villages and lose their agricultural livelihoods and jobs. The number of food-insecure people almost doubled from 7.7 million in 2017 to 13.1 million in 2018, making access to food a daily struggle for a significant part of the Congolese population [6]. The health and nutritional status of the children under 5 years of age are have been impacted by these years of armed conflict and instability: approximately 42% are stunted, 6% are wasted, 23% are underweight, and 47% are anemic (< 11.0 g/dl); Among children 6–23 months, only 18 and 37% receive the WHO recommended minimum dietary diversity and meal frequency each day, respectively; Furthermore, the under-5 mortality rate is 70 per 1000 live births [7]. Thus, undernutrition and suboptimal IYCF practices remain serious public health concerns in DRC.

To address inadequate IYCF practices, the Ministry of Public Health has developed a program named “Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergency”. This program aimed to provide concise, practical guidance on how to ensure appropriate IYCF in emergencies [8].

To date, there has been no published report on infant complementary feeding practices in South Kivu, a city that has the highest stunting rate among children under 5 years of age in DRC (48%) [7]. Yet growing evidence suggests that suboptimal IYCF practices may be a major contributor to the high prevalence of stunting in Eastern DRC [9,10,11]. Therefore, context-specific information on infant complementary feeding practices is needed as eating habits differ according to the tribes and customs in DRC. This study sought to assess the prevalence of minimum acceptable diet, as well as identify associated factors of adequate minimum acceptable diet, among children under 2 years of age in two health zones in South Kivu, Eastern DRC. Apart from a better understanding of the realities of infant complementary feeding practices, this study could generate evidence of a better practice of IYCF in an economic, political, social, and health context of precariousness, particularly to the context of the DRC.

Methods

Study design and setting

This community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in August 2019 in 2 Health Zones of South Kivu (Eastern DRC): Ibanda Health Zone, an urban area, and Kabare Health Zone, a rural one. The Health Zone is a geographical area contained within the limits of an administrative territory, comprising a population of at least 100,000 inhabitants. A Health Area is a geographical area consisting of a group of villages (in rural areas) or streets (in urban areas) with a population size of 10,000 inhabitants [12]. Ibanda Health Zone was selected by simple random sampling from the 3 Health Zones of Bukavu urban city (Kadutu, Bagira, Ibanda); Kabare Health Zone was selected also by simple random sampling from 5 surrounding rural areas of Bukavu (Nyantende, Walungu, Kabare, Katana, Miti-Murhesa). Each of these 2 selected Health Zones encompasses 16 Health Areas.

The Ibanda Health Zone is located in the municipality of Ibanda, city of Bukavu, in the South Kivu province of DRC. Bounded on the north by Lake Kivu and on the east by Rwanda, Ibanda Health Zone is an area with mountainous terrain, clay soil, grassy vegetation and a tropical highland climate. At the last census in 2018, it had a recorded population of 452,608 with a population density of 32 per km2. Infants < 24 months of age were estimated at 10,275. The main activities are small-scale trading and administration. Secondary activities are subsistence agriculture, small livestock farming and artisanal fishing. The staple food is cassava, cereals (maize, rice and sorghum), other tubers (taro, sweet and white potatoes) and bananas. These foods are generally served with vegetables, fish, beans and meat, which helps to balance the family dish. On average, two to three meals are consumed per day [13].

Kabare Health Zone is located in the Kabare administrative zone of South Kivu province in the DRC. It is situated 17 km from the city of Bukavu. It is an area with high plains and hills at elevations between 900 and 1900 m, with a tropical highland climate. At the last census in 2018, it had a recorded population of 213,882 with a very high population density of 856 per km2. Infants under 24 months of age were estimated at 12,800. The population of this area is devoted to agriculture, livestock and small-scale trade. Bananas, cassava, taro, sweet and white potatoes, corn and sugar cane are the main crops grown there. However, the soil is not very fertile, and most of the population of the area leaves the fields to sell labor in the city of Bukavu [14].

Eligibility criteria

The study included mothers with children aged 6–23 months old with the following characteristics: (i) Infants aged between 6 and 23 months; (ii) residence in the study area; (iii) infants without chronic debilitating illnesses such as cerebral palsy, congenital heart disease, Down syndrome, cleft lip/palate; and (iv) parental consent.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using Emergency Nutrition Assessment 2011 software, considering an absolute precision of 5% at the 95% confidence level, a design effect of 1.5 and a 52% prevalence of minimum acceptable diet, estimated based on a study conducted in Western Indonesia [15]. Allowing for 20% refusals and incomplete questionnaires, the required sample size was 750. Thus, we projected a sample of 375 in each Health Zone.

Sampling procedure of the study

In each Health Zone, a complete list of households with an infant between 6 and 24 months of age was obtained through a prior survey. This list served to identify and create sampling frame and apply the systematic random sampling to select the study samples, in order to assure the selection of representative sample from each health area.

Ten health extension workers and one public health professional were recruited as data collector and supervisor respectively. Data were collected in a separate room, in the absence of other relatives. We used face-to-face interview during house-to-house visit from mothers who had an infant between 6 and 24 months of age using structured questionnaire. The questionnaire contained the information on sociodemographic characteristics of participants and infant feeding practices as proposed by WHO. To determine household socioeconomic status, a household wealth score was computed as proposed by Bangirana et al. [16] based on the material possession of several items (electricity, radio, bike, motorbike, car) and on several characteristics of the house such as material used for the walls and for the roof. The wealth score of a household was obtained by summing points attributed to the above items and ranged from 1 to 11. We determined the child’s age based on the date of birth (obtained either from birth certificate, child health record booklet or baptismal card) and the date of the survey. The mother’s school level was subdivided into two classes: low (for mothers unschooled or primary school), and good (for those having secondary school or university). The household socioeconomic status was categorized into two classes: good (for households with medium or high socioeconomic level), and low.

For data quality control, the questionnaire was first developed in French and translated to local language (Swahili and Mashi language) and then back-translated to French by an independent translator for consistency. French version of the survey is provided in the Supplementary Appendix. Training was given to health extension workers and supervisor for 2 days. The questionnaire was pre-tested in 19 (5%) mothers in Ibanda Health Zone and 19 (5%) mothers in Kabare Health Zone, which were not included in actual study, to assess the content and approach of the questionnaire. To assure the quality of the data, the supervisor and investigator closely reviewed the data collection technique on daily basis, reviewed the filled questionnaire for completeness and returned any incomplete questionnaire to the data collectors for correction. There was also debriefing every day.

Operational definitions

Introduction of solid, semi-solid or soft foods

Children 6–7 months who received solid, semi-solid or soft foods at least once on the day preceding the survey date [17].

Minimum meal frequency

Breastfed children 6–23 months who were fed a minimum recommended number of times in the previous day of the survey. Minimum is defined as 2 times for breastfed infants 6–8 months, 3 times for breastfed children 9–23 months, 4 times for non-breastfed children 6–23 months [17].

Minimum dietary diversity

Children 6–23 months who received in the previous day of the survey four or more food groups out of seven food groups: (i) grains, roots and tubers; (ii) legumes and nuts; (iii) dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese); (iv) eggs; (v) flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry and liver/organ meats); (vi) vitamin-A-rich fruits and vegetables; and (vii) other fruits and vegetables [17]. WHO considers the cut-off of at least 4 of the above 7 food groups above because the consumption of foods from at least 4 food groups would mean that in most populations the child had a high likelihood of consuming at least one animal-source food and at least one fruit or vegetable that day, in addition to a staple food (grain, root or tuber) [17].

Minimum acceptable diet

Children 6–23 months old who met age-specific minimum recommended diet diversity and minimum recommended meal frequency and consumed a source of dairy (or were breastfed) in the previous day of the survey [17]. The minimum acceptable diet indicator was expressed as dichotomous variable categorized as “adequate minimum acceptable diet” and “inadequate minimum acceptable diet”. A child who met both the minimum dietary diversity and the minimum meal frequency was categorized as “adequate minimum acceptable diet”, and a child who did not meet either or both the minimum dietary diversity and the minimum meal frequency as “inadequate minimum acceptable diet”.

Statistical data analyses

Data were entered and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows version 25 (SPSS Inc. Version 25.0, Chicago, Illinois). Characteristics of mothers and infants were summarized as mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables with a normal distribution, or as median and range for continuous variables with a non-normal distribution, and as number or percentages for categorical variables. Normality of continuous variables was explored visually (Q-Q plots and histogram) and numerically (Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests). Proportions were compared by using either the χ2 or the Fisher exact test. The sociodemographic variables were selected on the basis of previous literature. They were imported into the multiple regression model on the basis of a value p ≤ 0.25 and/or on the basis of biological plausibility. The unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios with their 95% confidence intervals were used to measure the association between the variables and minimum acceptable diet. The significance level was fixed at 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Université Catholique de Bukavu (UCB/CIES/NC/08/2018). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants as well as from infants’ parents.

Results

The study included 742 mothers with children aged 6–23 months old (371 in Kabare Health Zone and 371 in Ibanda Health Zone), yielding a 98.9% response rate. Their sociodemographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Eighty percent of households had a low socioeconomic level, and 55.8% of mothers had a low educational level. Low socio-economic and maternal educational levels were more prevalent in rural areas than in urban ones (p < 0.05). The postnatal care follow-up rate was 85.0%, higher in rural areas than in urban ones (p < 0.05).

Complementary feeding practices are summarized in Fig. 1 and Table 2. The majority, 727 (98%) and 631 (85%) infants received cereals-roots-tubers and legume-based foods respectively. The consumption of animal foods was low as only 31% consumed flesh foods and only 12% consumed eggs. Consumption of dairy products, eggs, fruits and vegetables was significantly lower for rural infants compared to urban ones (p < 0.05). About 64% of infants had minimum meal frequency, 34% had minimum dietary diversity, and 33% had minimum acceptable diet, with rates higher in urban area than in rural one for all these indicators (p < 0.05).

The multivariate analysis showed that residence area, attendance at postnatal care, household socioeconomic status, and maternal education status were statistically associated with minimum acceptable diet.

Mothers living in urban area were 2.36 times [Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) 2.39; 95% CI 1.43, 3.85] more likely to provide minimum acceptable diet to their child when compared to their counterparts. Similarly, higher odds of receiving minimum acceptable diet was observed among mothers who had postnatal care visits (AOR 1.68; 95% CI 1.12, 2.97). Likewise, mothers with secondary and post-secondary education were 1.83 times (AOR 1.83; 95% CI 1.20, 2.77) more likely to give recommended minimum acceptable diet compared to their counterparts. Finally, higher odds of receiving minimum acceptable diet was observed among mothers with good household socioeconomic status (AOR 1.72; 95% CI 1.14, 2.59) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study sought to assess the prevalence and associated factors of adequate minimum acceptable diet among children 6–23 months. Findings revealed that the prevalence of minimum acceptable diet was 33%. Residence in urban area, good maternal education status, good household socioeconomic status, and attendance to postnatal consultations were factors that may increase the minimum acceptable diet practices.

The prevalence of minimum acceptable diet found in this study is close to that reported in Nepal (29%) [18] and China (27%) [19]. Minimum acceptable diet prevalence ranging from 8 to 18% have been observed in India, Bhutan, Ethiopia and Malawi [20,21,22,23], while in Tanzania [24], Bangladesh [25], and Indonesia [15] they were 38, 42, and 48% respectively. The differences in health services, including health education and advice on breastfeeding and complementary feeding during prenatal and postnatal care, and region-dependent feeding cultural practices could be the factors explaining these differences.

The acute nature of emergency situations such as those observed in Eastern DRC challenges optimal feeding practices. They may increase the likelihood of not breastfeeding, as well as the risks of artificial feeding and inappropriate complementary feeding, with potentially devastating short- and long-term implications on malnutrition, illness and mortality [26].

In our report, urban area appeared better in several aspects of complementary feeding practices than rural area. This might be the result of cumulative effect of a series of more favorable conditions, including better socioeconomic and educational conditions, in turn leading to better caring practices for children and their mothers. A study analyzing Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from 36 developing countries revealed that for the same reasons, the prevalence of malnutrition was higher in rural than in urban areas [27].

The association between attendance at postnatal care and adequate minimum acceptable diet is consistent with study findings in East African region and India [28,29,30,31,32]. Mothers’ education on complementary feeding practices during these visits is the factor underlying this association. In DRC’s health system, children’s growth monitoring is conducted in every health facility according to the national nutrition program. In the outreach clinics, health workers monitor the weight of children using growth charts, and provide nutrition education to mothers or caregivers of children. These activities also provide an opportunity to discourage harmful traditional beliefs that might inhibit child feeding practices, and to early recognition of signs of undernutrition, any illness and manage them accordingly [33].

Our findings show that more than 85% of the mothers attended at postnatal consultations. Surprisingly, the prevalence of minimum acceptable diet remained low. The low household socioeconomic status could be the main explanatory factor. Indeed, our study showed that about 80% of households had a low socio-economic status. This finding emphasizes the role of socio-economic status on feeding practices. Households with high socioeconomic status are more likely to be food secure, thus they can afford to provide the minimum acceptable diet to their children [34]. Several studies have also shown that improved household wealth has a significant effect on adequate complementary feeding practices [31, 35,36,37,38].

Consistent with studies conducted in China [19] and Ethiopia [39], the current study also found that mothers with secondary and post-secondary education had higher odds of adequate minimum acceptable diet. The possible reason might be that education is directly linked to women’s autonomy, changes in traditional beliefs and women’s control over household resources [40]. Hence educated mothers are more likely to understand information provided through health and nutritional programmes regarding complementary feeding practices [41].

Three systematic reviews [42,43,44] examined the effectiveness of infant’s complementary feeding interventions. The socioeconomic status of caregivers, maternal education level, and postnatal care have been identified as main factors that may influence infant’s complementary feeding practices. Nevertheless, the results of the 3 systematic reviews demonstrated that interventions that provide education to mothers will significantly improve complementary feeding knowledge and practices. When population is food secure, educational strategies alone can improve feeding practices. The case is different in the context of food insecurity or political trouble.

Study limitations

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, the recall bias may be possible and affect the validity of the results. However, this bias was minimized since most data related to infant’s complementary feeding practices were based on a 24-h recall method. Another limitation is the social desirability bias. Finally, the cross-sectional design does not allow for causal inference.

Conclusion

In the context of South Kivu (DRC), our findings reveal a low prevalence of adequate minimum acceptable diet among infants between 6 and 23 months of age. Overall, the residence area, mother’s educational status, household wealth, and postnatal care attendance were factors positively associated with adequate minimum acceptable diet. These findings suggest policy-makers to focus on improving and making effective behavior change, strengthening education of mothers, as well as improving complementary feeding practices for children through food security, health care utilization, and improved household socioeconomic status.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DRC:

-

Democratic Republic of Congo

- IYCF:

-

Infant and young child feeding

- MICS:

-

Multiple indicator cluster survey

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PNC:

-

Postnatal care

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for the social sciences

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- UNICEF:

-

United Nations Children’s Fund

References

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Sustainable development goals. 2015. https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/brochure/SDGs_Booklet_Web_En.pdf

Black RE, Victoria CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, De Onis M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427–51 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X.

UNICEF, WHO & World Bank Group (WB). Levels and trends in child malnutrition. 2018. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-6138(96)90067-4.

Mosley WH, Chen LC. An analytical framework for the study of child survival in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(2):140–5 Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/71801.

WHO. Infant and young child feeding. Model Chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44117/9789241597494_eng.pdf?sequence=1

World Food Programme (WFP) Democratic Republic of Congo. Emergency situation report #13. 2019. Available from: https://www.wfp.org/https://www.wfp.org/publications/situation-report-democratic-republic-congo

INS. Enquête par grappes à indicateurs multiples, 2017–2018, rapport de résultats de l’enquête. Kinshasa, République Démocratique du Congo. Available from: https://espkinshasa.net/rapport-mics-2018/. Accessed 21 Mar 2020.

République Démocratique du Congo. Alimentation du Nourrisson et du Jeune Enfant dans les situations d’urgence. Manuel d’orientation opérationnelle; 2019. p. 33. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/manuel_d_orientation_anje_u_rdc_14_mars_19_gtt_anje_cluster.pdf

Kandala NB, Madungu TP, Emina JB, Nzita KP, Cappuccio FP. Malnutrition among children under the age of five in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC): does geographic location matter? BMC Public Health. 2011;11:261 Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-261.

Kandala NB, Emina JB, Nzita PD, Cappuccio FP. Diarrhea, acute respiratory infection, and fever among children in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(9):1728–36 Available at: https://doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.004.

Balaluka GB, Nabugobe PS, Mitangala PN, Cobohwa NB, Schirvel C, Dramaix MW, et al. Community volunteers can improve breastfeeding among children under six months of age in the Democratic Republic of Congo crisis. Int Breastfeed J. 2012;7(1):2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4358-7-2.

République Démocratique du Congo. Recueil des normes de la zone de santé. Kinshasa. 2006. Available from: https://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/training/analysing_health_systems/5_normes_de_la_zone_de_sante_06.pdf

Action Against Hunger. Enquête Nutritionnelle Anthropométrique : Zone de Santé d’Ibanda. [Nutritional Anthropometric Study: health zone Ibanda]. New York: Action Against Hunger; 2011. Available from: https://www.actionagainsthunger.org/sites/default/files/publications/ACF-NUT-DRC-South-Kivu-Ibanda-2008-06-FR.pdf

Action Against Hunger. Enquête Nutritionnelle Anthropométrique : Zone de Santé de Kabare. [Nutritional Anthropometric Study: health zone Kabare]. New York: Action Against Hunger; 2011. Available from: https://www.actionagainsthunger.org/sites/default/files/publications/Enquete_Nutritionnelle_Anthropometrique_Zone_de_Sante_de_Kabare_Province_du_Sud-Divu_DRC_02.2012.pdf

Dewanti AJ, Muslimatun S, Iswarawanti ND, Khusun H. Minimum acceptable diet and factors related among children aged 6-23 months in Bekasi municipality West Java province Indonesia. Asian J Microbiol Biotechnol Environ Sci. 2015;17(2):415–21 Available from: http://www.envirobiotechjournals.com/article_abstract.php?aid=5981&iid=191&jid=1.

Bangirana P, John CC, Idro R, Opoka RO, Byarugaba J, Jurek AM, et al. Socioeconomic predictors of cognition in Ugandan children: implications for community interventions. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):2–7 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0007898.

WHO, UNICEF, USAID, FANTA, AED, UC DAVIS, IFPRI. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices part 2: measurement. Geneva: The World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44368/9789241599757_eng.pdf?sequence=1

Lamichhane DK, Leem JH, Kim HC, Park MS, Lee JY, Moon SH, et al. Association of infant and young child feeding practices with under-nutrition: evidence from the Nepal demographic and health survey. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2016;36(4):260–9 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/20469047.2015.1109281.

Duan Y, Yang Z, Lai J, Yu D, Chang S, Pang X, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding rate and complementary feeding indicators in China: a national representative survey in 2013. Nutrients. 2018;10(2):1–9 Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10020249.

Menon P, Bamezai A, Subandoro A, Ayoya MA, Aguayo V. Age-appropriate infant and young child feeding practices are associated with child nutrition in India: insights from nationally representative data. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11(1):73–87 Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/mcn.12036?src=getftr.

Campbell RK, Aguayo VM, Kang Y, Dzed L, Joshi V, Waid J, et al. Infant and young child feeding practices and nutritional status in Bhutan. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;14:1–6 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12762.

Mulat E, Alem G, Woyraw W, Temesgen H. Uptake of minimum acceptable diet among children aged 6–23 months in orthodox religion followers during fasting season in rural area, Dembecha, north West Ethiopia. BMC Nutr. 2019;5:1–10 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-019-0274-y.

Nkoka O, Mhone TG, Ntenda PAM. Factors associated with complementary feeding practices among children aged 6–23 mo in Malawi: An analysis of the Demographic and Health Survey 2015-2016. Int Health. 2018;10(6):466–79 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihy047.

Vitta BS, Benjamin M, Pries AM, Champeny M, Zehner E, Huffman SL. Infant and young child feeding practices among children under 2years of age and maternal exposure to infant and young child feeding messages and promotions in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12:77–90 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12292.

Zongrone A, Winskell K, Menon P. Infant and young child feeding practices and child undernutrition in Bangladesh: insights from nationally representative data. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(9):1697–704 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980012001073.

IFE Core Group. Complementary feeding of infants and young children in emergencies. Evaluating the specific requirements for realising a dedicated complementary feeding in emergencies training resource (Module 3); a preliminary scoping review of current resources (Phase I). Oxford. 2009. Available from: https://www.ennonline.net/attachments/965/cfe-review-enn-ife-core-group-oct-2009.pdf

Smith LC, Ruel MT, Ndiaye A. Why is child malnutrition lower in urban than in rural areas? Evidence from 36 developing countries. World Dev. 2005;33(8):1285–305 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.03.002.

Gewa CA, Leslie TF. Distribution and determinants of young child feeding practices in the East African region: Demographic health survey data analysis from 2008-2011. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015;34(1):1–14 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-015-0008-y.

Tessema M, Belachew T, Ersino G. Feeding patterns and stunting during early childhood in rural communities of Sidama South Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;14:1–12 Available from: https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2013.14.75.1630.

Victor R, Baines SK, Agho KE, Dibley MJ. Factors associated with inappropriate complementary feeding practices among children aged 6-23 months in Tanzania. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10(4):545–61 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00435.x.

Patel A, Pusdekar Y, Badhoniya N, Borkar J, Agho KE, Dibley MJ. Determinants of inappropriate complementary feeding practices in young children in India: secondary analysis of National Family Health Survey 2005-2006. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(Suppl. 1):28–44 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00385.x.

Senarath U, Dibley MJ. Complementary feeding practices in South Asia: analyses by the South Asia infant feeding research network. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(Suppl 1):5–10 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00371.x.

Ministère de la santé, République Démocratique du Congo. Nutrition à assise communautaire. Kinshasa; 2015. Available from: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/manuel_nac_valide_edite.pdf. Accessed 21 Mar 2020.

Amugsi DA. Child care practices, resources for care, and nutritional outcomes in Ghana: findings from demographic and health surveys. PhD dissertation, University of Bergen. 2015.

Batal M, Boulghourjian C, Akik C. Complementary feeding patterns in a developing country: a cross-sectional study across Lebanon. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16(2):180–6 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20799572.

Joshi N, Agho KE, Dibley MJ, Senarath U, Tiwari K. Determinants of inappropriate complementary feeding practices in young children in Nepal: secondary data analysis of demographic and health survey 2006. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(Suppl. 1):45–59 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00384.x.

Kabir I, Khanam M, Agho KE, Mihrshahi S, Dibley MJ, Roy SK. Determinants of inappropriate complementary feeding practices in infant and young children in Bangladesh: secondary data analysis of demographic health survey 2007. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(Suppl. 1):11–27 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00379.x.

Ng CS, Dibley MJ, Agho KE. Complementary feeding indicators and determinants of poor feeding practices in Indonesia: a secondary analysis of 2007 demographic and health survey data. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(5):827–39 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980011002485.

Ahmed KY, Page A, Arora A, Ogbo FA. Trends and factors associated with complementary feeding practices in Ethiopia from 2005 to 2016. Matern Child Nutr. 2020;16(2):1–17 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12926.

Vikram K, Vanneman R, Desai S. Linkages between maternal education and childhood immunization in India. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:331–9 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.043.

Demilew YM. Factors associated with mothers’ knowledge on infant and young child feeding recommendation in slum areas of Bahir Dar City, Ethiopia: cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:191 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2510-3.

Lassi ZS, Das JK, Zahid G, Imdad A, Bhutta ZA. Impact of education and provision of complementary feeding on growth and morbidity in children less than 2 years of age in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(Suppl.3):S13 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S13.

Dewey KG, Adu-Afarwuah S. Systematic review of the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. Matern Child Nutr. 2008;4(Suppl 1):24–85 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00124.x.

Imdad A, Yakoob MY, Bhutta ZA. Impact of maternal education about complementary feeding and provision of complementary foods on child growth in developing countries. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl. 3):S25 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S25.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Coordination of the Provincial Nutrition Programme/South Kivu/Provincial Health Division (Division Provinciale de la Santé, DPS) for the logistical support throughout the survey. We express our sincere gratitude to the data collection team members for their hard work and commitment, and for working tirelessly during the data collection phase. Finally, we thank all women, infants and their families in the Ibanda and Kabare health zones for their participation in this survey.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RMK and DVDL designed the study and reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. SN, BRC, AB and KCM were responsible for collecting the data. GAN supervised the team of surveyors. GAN and JBK analyzed the data. RMK wrote the manuscript. RMK and DVDL critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Université Catholique de Bukavu (UCB/CIES/NC/08/2018). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants as well as from infants’ parents.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kambale, R.M., Ngaboyeka, G.A., Kasengi, J.B. et al. Minimum acceptable diet among children aged 6–23 months in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr 21, 239 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02713-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02713-0