Abstract

Background

Metformin is widely used in pregnancy to treat gestational diabetes mellitus and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Association between PCOS and developmental delay in offspring, and larger head circumference of metformin-exposed newborns has been reported. The objective of this study was to explore whether metformin exposure in utero had any effect on offspring cognitive function.

Method

The current study is a follow-up of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies which were conducted at 11 public hospitals in Norway In the baseline studies (conducted in 2000–2003, and 2005–2009), participants were randomized to metformin 1700 and 2000 mg/d or placebo from first trimester to delivery. There was no intervention in the current study. We invited parents of 292 children to give permission for their children to participate; 93 children were included (mean age 7.7 years). The follow-up study was conducted in 2014–2016. The Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence version III and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children version IV were applied for cognitive assessment. Androstenedione and testosterone were measured in maternal blood samples at four time-points in pregnancy.

Results

We found no difference in mean, full scale IQ in metformin (100.0 (SD 13.2)) vs. placebo-exposed (100.9 (SD 10.1)) children. There was an association between metformin exposure in utero and borderline intellectual function of children (full scale IQ between 70 and 85). Free testosterone index in gestational week 19, and androstenedione in gestational week 36 correlated positively to full scale IQ.

Conclusions

We found no evidence of long-term effect of metformin on average child cognitive function. The increase of borderline intellectual functioning in metformin-exposed children must be interpreted with caution due to small sample size.

Trial registration

The baseline study was registered on 12 September 2005 at the US National Institute of Health (ClinicalTrials.gov) # NCT00159536.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Metformin is an old, low cost, oral antidiabetic drug used to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Metformin passes the placental barrier, thereby potentially affecting the foetus [1]. A recent large exploratory case-control study on metformin-use in first trimester of pregnancy found no evidence of teratogenicity [2].

During the last four decades, prescription of metformin in pregnancy has increased, reflecting the increased prevalence of overweight, obesity and GDM [3]. Women with PCOS have increased risk of pregnancy complications, such as GDM, preterm delivery, preeclampsia, hypertension, and small for gestational age babies [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Our research group has recently reported on the reduced incidence of late miscarriage and preterm deliveries in an individual patient data meta-analysis of three metformin vs. placebo-controlled RCTs: the Pilot study, the PregMet study and the PregMet 2 study [10,11,12]. Interestingly, in all three studies, metformin exposed offspring had a larger head, both at gestational age 32 weeks and at birth [13]. Follow-up of the children from the PregMet study also showed that metformin-exposed children at 4 and 8 years og age, had higher BMI, waist circumference, waist-to-height ratio and prevalence of obesity than those exposed to placebo [14, 15].

Recent research suggests higher risk of developmental delay and neurodevelopmental disorders among children born to mothers with PCOS, due to potential exposure to a hyperandrogen environment and insulin resistance in utero [16,17,18]. Bell et al. found that maternal PCOS status was associated with developmental delay in offspring followed up through 3 years of age [16]. In a population-based study of register data in Sweden, Kosidou et al. found an increased risk of autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children of mothers diagnosed with PCOS, supporting the hypothesis of potential negative neurodevelopmental effects of a hyperandrogen environment in utero [17, 18].

In a follow-up of a Finnish RCT on pregnant women with GDM, Ijäs et al. reported no difference in motor, social and language development at 18 months of age between metformin- and insulin-exposed offspring [19]. Two studies have examined neurodevelopmental outcome in 2-year-old children born to mothers with GDM treated with metformin or insulin during pregnancy, reporting no difference between the two groups [20, 21]. In the present study, the primary aim was to explore the cognitive function of children born to mothers with PCOS, exposed to metformin vs. placebo in utero. The secondary aim of the study was to investigate associations between maternal androgen levels in pregnancy and subsequent cognitive function of children.

Methods

The present study (CogMet study) is a follow-up study of children whose mothers participated in “the Pilot study” and “the PregMet study”. Both were randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded studies, assessing the potential of metformin to reduce pregnancy complications in women with PCOS.

The pilot study

Between 2000 and 2003, 40 women aged 18–40 with PCOS and with singleton pregnancies were included between 5 and 12 weeks of gestation at the Trondheim University Hospital. Eighteen were randomized to metformin (1700 mg daily) and 22 to placebo throughout pregnancy [10].

The PregMet study

Between 2005 and 2009, 257 pregnant women aged 18–45 years with PCOS according to the Rotterdam criteria [22] were included with 274 singleton pregnancies at 5–12 weeks of gestation, at 11 study centers in Norway. Seventeen women participated twice. Participants were randomized to metformin (2000 mg daily) or placebo throughout pregnancy, and 80% had a self-reported intake of > 85% of the tablets [11].

The CogMet study

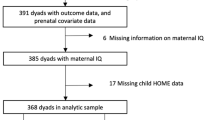

In all, 292 children were eligible, and parents were invited to allow their children to participate in a follow-up with cognitive testing; 37 children from the Pilot study and 255 children from the PregMet study (Fig. 1). A total of 93 children were tested between April 2014 to June 2016, 52 in the metformin group, and 41 in the placebo group. The staff collecting the data and performing the cognitive testing were blinded to original randomization allocation. Information on gender, age and socio-economic status was obtained by standardized interviewer-administered questionnaires. Weight was measured with a digital weighing scale. Height was measured with a stadiometer (Seca, Germany). Head circumference was measured with a measuring tape over the most prominent part of the occiput, and just above the supraorbital ridge.

Cognitive assessment

Intelligence quotient (IQ) is a measure of cognitive function. Intellectual disability is considered to be a score on standardized intelligence tests that is more than two standard deviations below the population mean in combination with reported difficulties in daily life functioning, according the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) [23]. This equals an IQ-score below 70. An IQ score within the normal range can be defined as a score within one standard deviation (SD) of the population mean (100), between 85 and 115 points. However, scores just below the normal range have been described as Borderline Intellectual Function in the DSM (IQ scores between approximately 70–85) and could also affect the individual’s ability to function in daily life [24].

The cognitive assessment was performed by three students specializing in clinical psychology, under the supervision of a clinical psychologist (HFØ) trained in cognitive testing. Testing took place during a single session with a fixed order of tasks. Age-appropriate Wechsler tests of cognitive ability were used for assessing full scale IQ (FIQ), IQ indices and subtest scores. The Wechsler tests are considered the gold standard in assessing intelligence, where different versions exist for preschool and school aged children. The Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence version III (WPPSI-III) was applied for children under the age of six, and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children version IV (WISC-IV) was applied for children above the age of six.

The WISC-IV consists of 15 subtests divided into scales that provide Verbal IQ and Performance IQ, respectively, in addition to FIQ. The verbal subtests are further divided into two indices: Verbal Comprehension and Working Memory. The performance scale tasks are divided into the Perceptual Organization Index and the Processing Speed Index. WPPSI-III consists of 14 subtests that are divided into the same scales and indices as the WISC-IV. The WPPSI-III and the WISC-IV group means are identical in the overlapping age-bands, and their respective FIQ scores are highly inter-correlated (i.e. r = 0.89) [25].

Androgen analyses

In the original RCTs maternal blood was drawn at the time of study inclusion, and in gestational weeks 19, 32 and 36. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS), sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), and testosterone in maternal venous serum were analyzed. The DHEAS and SHBG levels were analyzed in single measurements by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay techniques with the reagents and calibrators supplied by the manufacturer (DRG Instruments GmbH). Testosterone and androstenedione were analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). In the analysis, plasma samples were extracted by supported liquid extraction and the eluate evaporated and reconstituted before analysis on LC-MS/MS. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) were 3.6 and 4.4% for DHEAS, and 2.9 and 11.4% for testosterone, respectively. The intra-assay CV was 6.6% for SHBG, and the inter-assay CV was 5.5% in fetal samples (lower values) and 24.1% in maternal samples. The free testosterone index (FTI) was calculated as (testosterone/SHBG) × 100 [26].

Statistical analysis

Data entry, management and analyses were performed at the Department of Clinical and Molecular Medicine at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology on IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM, SPSS inc USA, Chicago IL). Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 (IBM, SPSS inc USA, Chicago IL). Differences between the groups were compared by independent t-test for continuous variables or the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Linear regression analyses were used to compare continuous variables adjusted for parental education. Normality of residuals was confirmed by visual inspection of qq-plots. For calculation of anthropometric z-scores at birth, Niklasson’s standard values from a large Swedish population were applied [27]. The standard is gestational age adjusted and is based on singleton fetuses without chromosome abnormalities or major birth defects. At follow-up, z-scores for length/height, weight, and head circumference were computed from Norwegian growth references. These are built on anthropometric measurements of live-born children between 37 and 42 weeks of gestation, without congenital anomalies or diseases that could affect growth, and whose parents were from Norway or northern Europe [28]. Correlation coefficients ranging 0–0.29 were considered as small, 0.3–0.59 as moderate, and 0.6–1 as high. A significance level of 0.05 was chosen, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported where relevant.

Results

The response rate for the follow-up was 32% (93 out of 292). There was no difference between participants and non-participants regarding maternal baseline data, pregnancy outcomes and neonatal data (Additional file 1: Table S1). Maternal baseline data at original study entrance in early pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes were comparable between the metformin and placebo groups (Table 1). There were no significant between-group differences in neonatal data, except larger head circumference and head circumference z-score of the newborns in the metformin group (Table 1). There was no difference in the prevalence of asthma, eczema, heart conditions, bowel disease, constipation, diarrhea, abnormal growth, recurrent infections or hospital admissions between the metformin vs. placebo exposed children. Parental education and socioeconomic status at follow-up were comparable between groups (Table 2). Mean age at follow-up was 7.7 years in both study groups (age range 5–14 years). All anthropometric measures, including Tanner stage development of the children at follow-up, were also comparable between groups (Table 2).

The mean FIQ in the metformin and placebo groups were 100.0 (SD 13.2) and 100.9 (SD 10.1) respectively, which correspond to the average FIQ score in the background population. There was no statistically significant difference in mean FIQ scores between metformin and placebo exposed children at the follow-up (Table 3). Further, there was no statistically significant between-group difference in scores on the subscales: verbal comprehension, working memory, perceptual organization or processing speed (Table 3). These results did not change after adjustment for maternal/parental educational level (Table 4). None of the children had FIQ < 70 corresponding to intellectual disability. Ten children had FIQ < 85 corresponding to borderline intellectual function, 9 in the metformin and 1 in the placebo group, (p = 0.039). There were no significant differences regarding gender, prematurity, birth weight, head circumference or maternal baseline data between participants with borderline intellectual function and participants with normal intellectual function (data not shown). Baseline characteristics regarding maternal and neonatal data of children with borderline intellectual function are shown in Table 5.

Correlation between androgen levels at different time points in pregnancy and IQ-scores of children at follow-up, are shown in Table 6. There was a significant positive correlation between FIQ and maternal FTI measured at gestational week 19 (p = 0.041), and between androstenedione measured at gestational week 36 (p = 0.049). We found no correlation between maternal testosterone, androstenedione and FTI at any time of pregnancy in any subdomain scores of WISC-IV/WPPSI (Table 6). However, all correlation coefficients were small.

Discussion

The main finding of the present study is that metformin exposure in utero did not seem to affect mean cognitive function of children born to women with PCOS. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first follow-up of cognitive function of children exposed to metformin in utero in a placebo-controlled RCT.

The study question arose from the surprising finding of significantly larger newborn head circumference in the two RCTs, the Pilot and the PregMet studies [10, 13], which were reproduced in a third larger RCT, the PregMet2 study [12]. This led to the question of whether the larger head circumference in the metformin-exposed offspring translated to altered cognitive function in the offspring. On a group level, larger head circumference at birth is associated with better cognitive function [29, 30]. However, also autistic spectrum disorders associate positively with large head size [31]. In the general population the measures of cognitive function follow a normal distribution. The prevalence of intellectual disability (FIQ < 70) is about 1%, and intellectual disability is found to be associated with several disorders, such as autism spectrum disorders, ADHD, conduct disorders, epilepsy and sensory and motor impairments [32]. It is well established that cognitive function is dependent on both genetic and environmental factors [33, 34]. Among these are: sociocultural and family environment, education, nutrition, early stress, exposure to toxins, drugs or alcohol prenatally or in childhood, and perinatal complications [33, 34]. The potential identification of metformin as a factor that could alter cognitive function in prenatally exposed offspring is of great importance. While impaired cognitive function could represent social, behavioral and educational challenges for the individual and costs for society, good cognitive function is associated with beneficial outcome for the individual [32, 35]. Intelligence is considered a relatively stable measure throughout life [36]. In a Danish cohort-study, Flensborg-Madsen and colleagues found that birth weight and head circumference at birth was positively associated with intelligence in adulthood, and persisted into midlife [37].

At birth, metformin-exposed offspring in the CogMet study had significantly larger head circumference z-scores (Table 1). At the present follow-up, the difference in HC z-score was no longer significant (Table 2), and there was no statistically significant difference in mean IQ-scores of children in the two study groups (Table 3). However, exploring children with FIQ-score < 85, we found that there were more metformin-exposed children with borderline intellectual function compared to unexposed children. This is a surprising finding that should be interpreted with great caution due to small study size. We have no mechanistic/cellular biologic explanations for our findings and can only speculate. Metformin passes the blood-brain barrier and has been shown in experimental studies to have a neuroprotective effect in cerebral damage such as oxidative stress, blood-brain barrier disruption and inflammation [38]. Metformin has a mild and specific inhibitory effect on mitochondrial respiratory chain complex activity, switching the cell from anabolic to catabolic state [39]. Theoretically, this might affect the developing fetal brain.

Based on previous results of increased head circumference of metformin exposed newborns [13], and the results of Smithers et al. and Gale et al. of positive associations between head size and cognitive function [29, 30], we would have expected an opposite result. However, the total prevalence of individuals with FIQ < 85 in the study population, does not exceed the expected number based on an assumption of normal distribution of IQ scores. The FIQ scores had a significant positive correlation to maternal education in the metformin group.

Nonetheless, these findings point to the importance of investigating cognitive function in children exposed to metformin in utero. The secondary aim of the present study was to investigate associations between maternal androgen levels and cognitive function in children. Previous research indicates that a hyperandrogenic environment in utero might be associated with impaired development and neurodevelopmental disorders such as ADHD and autism spectrum disorder [16,17,18]. We found statistically significant, but small, positive correlations of FIQ and maternal FTI at gestational week 19, and androstenedione at gestational week 36. However, these were the only statistically significant correlations among a large number of tests, and should therefore be interpreted with caution. We did not find convincing evidence for an association between hyperandrogen environment in utero and cognitive function in children.

Strengths and limitations

The well characterized cohort of women with PCOS and the randomized, placebo-controlled study design is a strength of the study. This is the first long-term follow-up on exposure of metformin versus placebo in utero of children including cognitive assessment, thereby an important contribution to the present base of knowledge regarding long-term consequences of metformin use in pregnancy. The main limitation of the present study is the relatively low number of participants, and a low response rate of only 32% of those invited. However, those who participated in the CogMet study did not differ at baseline from those who were invited, but chose not to participate (Additional file 1: Table S1). Particularly, there is a possibility that some children with low-to-borderline intellectual function were lost to follow-up due to the total burden of challenges these children and their families experience.

Conclusion

Previously reported larger head circumference at birth in metformin-exposed children did not translate into altered mean cognitive function at a follow-up at 7.7 years (mean age). However, more of the metformin exposed children had borderline cognitive function, which is an unexpected and unexplained finding. We found no convincing evidence of an association between a high maternal androgen level and altered offspring cognitive function. Our findings are important contributions to the current knowledge of long-term consequences of metformin use during pregnancy. More research on larger study populations is needed.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CV:

-

Coefficients of variation

- DHEAS:

-

Dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate

- DSM:

-

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

- FIQ:

-

Full-scale intelligence quotient

- FTI:

-

Free testosterone index

- GDM:

-

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- IQ:

-

Intelligence quotient

- PCOS:

-

Polycystic ovary syndrome

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SHBG:

-

Sex hormone binding globulin

- WISC-IV:

-

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children version IV

- WPPSI-III:

-

Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence version III

References

Vanky E, Zahlsen K, Spigset O, Carlsen SM. Placental passage of metformin in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(5):1575–8.

Given JE, Loane M, Garne E, Addor MC, Bakker M, Bertaut-Nativel B, Gatt M, Klungsoyr K, Lelong N, Morgan M, et al. Metformin exposure in first trimester of pregnancy and risk of all or specific congenital anomalies: exploratory case-control study. BMJ. 2018;361:k2477.

Lawrence JM, Andrade SE, Avalos LA, Beaton SJ, Chiu VY, Davis RL, Dublin S, Pawloski PA, Raebel MA, Smith DH, et al. Prevalence, trends, and patterns of use of antidiabetic medications among pregnant women, 2001-2007. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(1):106–14.

Fauser BC, Tarlatzis BC, Rebar RW, Legro RS, Balen AH, Lobo R, Carmina E, Chang J, Yildiz BO, Laven JS, et al. Consensus on women's health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the Amsterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored 3rd PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(1):28–38.e25.

Roos N, Kieler H, Sahlin L, Ekman-Ordeberg G, Falconer H, Stephansson O. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2011;343:d6309.

Boomsma CM, Eijkemans MJ, Hughes EG, Visser GH, Fauser BC, Macklon NS. A meta-analysis of pregnancy outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12(6):673–83.

Boomsma CM, Fauser BC, Macklon NS. Pregnancy complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Semin Reprod Med. 2008;26(1):72–84.

Palomba S, de Wilde MA, Falbo A, Koster MP, La Sala GB, Fauser BC. Pregnancy complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(5):575–92.

Kjerulff LE, Sanchez-Ramos L, Duffy D. Pregnancy outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):558.e551–6.

Vanky E, Salvesen KA, Heimstad R, Fougner KJ, Romundstad P, Carlsen SM. Metformin reduces pregnancy complications without affecting androgen levels in pregnant polycystic ovary syndrome women: results of a randomized study. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(8):1734–40.

Vanky E, Stridsklev S, Heimstad R, Romundstad P, Skogoy K, Kleggetveit O, Hjelle S, von Brandis P, Eikeland T, Flo K, et al. Metformin versus placebo from first trimester to delivery in polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized, controlled multicenter study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(12):E448–55.

Lovvik TS, Carlsen SM, Salvesen O, Steffensen B, Bixo M, Gomez-Real F, Lonnebotn M, Hestvold KV, Zabielska R, Hirschberg AL, et al. Use of metformin to treat pregnant women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PregMet2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diab Endocrinol. 2019;7(4):256–66.

Hjorth-Hansen A, Salvesen O, Engen Hanem LG, Eggebo T, Salvesen KA, Vanky E, Odegard R. Fetal growth and birth anthropometrics in metformin-exposed offspring born to mothers with PCOS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(2):740–7.

Hanem LGE, Stridsklev S, Juliusson PB, Salvesen O, Roelants M, Carlsen SM, Odegard R, Vanky E. Metformin use in PCOS pregnancies increases the risk of offspring overweight at 4 years of age: follow-up of two RCTs. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(4):1612–21.

Hanem LGE, Salvesen O, Juliusson PB, Carlsen SM, Nossum MCF, Vaage MO, Odegard R, Vanky E. Intrauterine metformin exposure and offspring cardiometabolic risk factors (PedMet study): a 5-10 year follow-up of the PregMet randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3(3):166–74.

Bell GA, Sundaram R, Mumford SL, Park H, Mills J, Bell EM, Broadney M, Yeung EH. Maternal polycystic ovarian syndrome and early offspring development. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(7):1307–15.

Kosidou K, Dalman C, Widman L, Arver S, Lee BK, Magnusson C, Gardner RM. Maternal polycystic ovary syndrome and the risk of autism spectrum disorders in the offspring: a population-based nationwide study in Sweden. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(10):1441–8.

Kosidou K, Dalman C, Widman L, Arver S, Lee BK, Magnusson C, Gardner RM. Maternal polycystic ovary syndrome and risk for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the offspring. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;82(9):651–9.

Ijas H, Vaarasmaki M, Saarela T, Keravuo R, Raudaskoski T. A follow-up of a randomised study of metformin and insulin in gestational diabetes mellitus: growth and development of the children at the age of 18 months. BJOG. 2015;122(7):994–1000.

Tertti K, Eskola E, Ronnemaa T, Haataja L. Neurodevelopment of two-year-old children exposed to metformin and insulin in gestational diabetes mellitus. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2015;36(9):752–7.

Wouldes TA, Battin M, Coat S, Rush EC, Hague WM, Rowan JA. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years in offspring of women randomised to metformin or insulin treatment for gestational diabetes. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016.

Revised 2003 Consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod2004, 19(1):41–47.

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Schalock RL, Borthwick-Duffy SA, Bradley VJ, Buntinx WHE, Coulter DL, Craig EM, Gomez SC, Lachapelle Y, Luckasson R, Reeve A, Shogren KA, Snell ME, Spreat S, Tassé MJ, Thompson JR, Verdugo-Alonso MA, Wehmeyer ML, Yeager MH. Intellectual disability: definition, classification, and Systems of Supports. 11th ed. Washington, DC: American Association of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; 2010.

Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms, and commentary. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Vanky E, Carlsen SM. Androgens and antimullerian hormone in mothers with polycystic ovary syndrome and their newborns. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(2):509–15.

Niklasson A, Albertsson-Wikland K. Continuous growth reference from 24th week of gestation to 24 months by gender. BMC Pediatr. 2008;8:8.

Juliusson PB, Roelants M, Nordal E, Furevik L, Eide GE, Moster D, Hauspie R, Bjerknes R. Growth references for 0-19 year-old Norwegian children for length/height, weight, body mass index and head circumference. Ann Hum Biol. 2013;40(3):220–7.

Smithers LG, Lynch JW, Yang S, Dahhou M, Kramer MS. Impact of neonatal growth on IQ and behavior at early school age. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e53–60.

Gale CR, O'Callaghan FJ, Bredow M, Martyn CN. The influence of head growth in fetal life, infancy, and childhood on intelligence at the ages of 4 and 8 years. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1486–92.

Bonnet-Brilhault F, Rajerison TA, Paillet C, Guimard-Brunault M, Saby A, Ponson L, Tripi G, Malvy J, Roux S. Autism is a prenatal disorder: evidence from late gestation brain overgrowth. Autism Res. 2018;11(12):1635–42.

Carr A, O'Reilly G. Diagnosis, classification and epidemiology. In: The handbook of intellectual disability and clinical psychology practice. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2016. p. 3–44.

Nisbett RE, Aronson J, Blair C, Dickens W, Flynn J, Halpern DF, Turkheimer E. Intelligence: new findings and theoretical developments. Am Psychol. 2012;67(2):130–59.

Neisser U, Boodoo G, Bouchard TJ Jr, Boykin AW, Brody N, Ceci SJ, Halpern DF, Loehlin JC, Perloff R, Sternberg RJ, et al. Intelligence: Knowns and unknowns. Am Psychol. 1996;51(2):77–101.

Szumski G, Firkowska-Mankiewicz A, Lebuda I, Karwowski M. Predictors of success and quality of life in people with borderline intelligence: the special school label, personal and social resources. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2018;31(6):1021–31.

Deary IJ, Yang J, Davies G, Harris SE, Tenesa A, Liewald D, Luciano M, Lopez LM, Gow AJ, Corley J, et al. Genetic contributions to stability and change in intelligence from childhood to old age. Nature. 2012;482(7384):212–5.

Flensborg-Madsen T, Mortensen EL. Birth Weight and Intelligence in Young Adulthood and Midlife. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6):e20163161.

Leech T, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn SC. The beneficial roles of metformin on the brain with cerebral ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Pharmacol Res. 2019;146:104261.

Viollet B, Guigas B, Sanz Garcia N, Leclerc J, Foretz M, Andreelli F. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin: an overview. Clin Sci (Lond). 2012;122(6):253–70.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by The Research Council of Norway, Novo Nordisk Foundation, St. Olavs University Hospital and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. The funders had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HG planned the study, conducted the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. LH contributed to the drafting of the manuscript, conduction of statistical analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. HØ contributed to data collection by supervising students who performed the cognitive testing and reviewed and revised the manuscript. EV conceptualized and designed the study, conducted data collection, contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Pilot study (project number 51–2000), the PregMet study (project number 145.04), and the CogMet study (project number 2014/96) were approved by the Committee for Medical Research Ethics of Health Region IV, Norway. Written, informed consent was obtained from each child’s parent or guardian before inclusion in the CogMet study. The declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines were followed throughout the studies.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 : Table S1.

Baseline data from the original PregMet study, according to participation vs. non-participation in the present follow-up study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Greger, H.K., Hanem, L.G.E., Østgård, H.F. et al. Cognitive function in metformin exposed children, born to mothers with PCOS – follow-up of an RCT. BMC Pediatr 20, 60 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-1960-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-1960-2