Abstract

Background

Children with medical complexity (CMC) denotes the profile of a child with diverse acute and chronic conditions, making intensive use of the healthcare services and with special health and social needs. Previous studies show that CMC are also affected by the socioeconomic position (SEP) of their family. The aim of this study is to describe the pathologic patterns of CMC and their socioeconomic inequalities in order to better manage their needs, plan healthcare services accordingly, and improve the care models in place.

Methods

Cross-sectional study with latent class analysis (LCA) of the CMC population under the age of 15 in Catalonia in 2016, using administrative data. LCA was used to define multimorbidity classes based on the presence/absence of 57 conditions. All individuals were assigned to a best-fit class. Each comorbidity class was described and its association with SEP tested. The Adjusted Morbidity Groups classification system (Catalan acronym GMA) was used to identify the CMC. The main outcome measures were SEP, GMA score, sex, and age distribution, in both populations (CMC and non-CMC) and in each of the classes identified.

Results

71% of the CMC population had at least one parent with no employment or an annual income of less than €18,000. Four comorbidity classes were identified in the CMC: oncology (36.0%), neurodevelopment (13.7%), congenital and perinatal (19.8%), and respiratory (30.5%). SEP associations were: oncology OR 1.9 in boys and 2.0 in girls; neurodevelopment OR 2.3 in boys and 1.8 in girls; congenital and perinatal OR 1.7 in boys and 2.1 in girls; and respiratory OR 2.0 in boys and 2.0 in girls.

Conclusions

Our findings show the existence of four different patterns of comorbidities in CMC and a significantly high proportion of lower SEP children in all classes. These results could benefit CMC management by creating more efficient multidisciplinary medical teams according to each comorbidity class and a holistic perspective taking into account its socioeconomic vulnerability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Childhood is widely recognised as one of the population groups that warrants special care and attention, even more so when they suffer chronic comorbidities and severe limitations – known as children with medical complexity (CMC) [1], one of the most vulnerable populations. Studies differ regarding the prevalence of CMC status, ranging between 0.4% [2] and 0.7% [3] of total child population, although it is rising, given the continuous increase in their survival rates [4,5,6,7,8].

Children in this population group have complex acute and chronic conditions, numerous and varied comorbidities (from cerebral palsy to congenital heart defects or cancer), a broad range of mental health and psychosocial needs, major functional limitations, and a higher rate of mortality [1, 2, 6, 9]. They are under the continuous care of multiple paediatric specialists and require access to specialised care units6. As such, the CMC status indicates a child with intensive use of healthcare services and special health and social needs [10, 11]. Although they represent a small proportion of the population, CMC account for a substantial proportion of healthcare costs [3], and impact on other externalities such as family resources, psychological stress, and social exclusion [12,13,14,15].

Previous studies have examined socioeconomic position (SEP) [16] and ethnic inequalities [17] in CMC [11], and found that the prevalence of life-limiting conditions is higher in non-white and the most deprived CMC in England [7]. In Catalonia, low-SEP children are twice as likely to be CMC than those at the highest socioeconomic level [18, 19]. However, a study conducted in Wales did not find an association between mortality rates in paediatric intensive care units and SEP, despite noting an increase in the most vulnerable categories, especially among some ethnic groups [17].

With few exceptions [2], the research to date has focused on CMC with diseases within intensive care units, where accessible data elements are often restricted to the hospital setting [4, 6,7,8, 20, 21]. A wider approach is essential in order to obtain evidence that can guide the coordination of healthcare resources targeted to the different CMC profiles more efficiently [1].

The aim of this study is to describe more accurately te pathologic patterns of CMC (by clustering health diseases [22, 23]) and their socioeconomic inequalities in order to better manage better their needs, plan healthcare services accordingly, and improve the care models in place.

Methods

Study population

We selected the CMC individuals from the population of Catalonia under the age of 15 in 2016 (1,189,325). CMC individuals were identified by GMA score [24], a risk tool which classifies each individual into a health status and a severity level group, using administrative data. The higher the GMA score, the greater the individual’s medical complexity. To construct GMA score, comorbidity and severity information is gathered automatically from the Catalan Health Surveillance System (CHSS) database, for present and previous years. Each person in contact with the Catalan health system has a GMA score; this scoring is used to stratify the population for the purposes of health planning [24, 25]. It is more accurate and yields less variability than other health risk tools, such as Clinical Risk Group (CRG) [25], and has been approved by the World Health Organisation [26] (see Additional file 1 for further details). According to the GMA percentiles, the population is distributed in relation to clinical complexity (P50 very low risk, P75 low risk, P85 moderate risk, P90 high risk, P99 very high risk, P99,5 extreme risk).

We identified the CMC population based on the children included in the top 0.5% of GMA scores (P99,5). This criteria was applied since: 1) stratification tools have proven useful in determining CMC [2, 3, 21, 27, 28]; 2) this is the highest level of complexity indicated by the GMA; 3) previous studies in Catalonia have found that 0.3% of the population were CMC [18]; and 4) concordance with the prevalence of CMC in other population studies [2, 3]. As a comparative group, we used the remainder of the child population (non-CMC), representing 99.5% of that population.

Data

We used two main sources of data: 1) The central registry of insured persons was used to obtain the reference population (as of January 1, 2016) based on their income level, employment status, and Social Security benefits; 2) the CHSS database includes detailed information on sociodemographic characteristics and medical diagnoses at an individual level in all contacts with primary care, emergency care, mental healthcare, long-term care services. All the historical comorbidities are updated if they are relevant, and it includes the whole population of Catalonia, since all citizens are granted universal health coverage.

Variables

The main outcome variable is the different classes obtained by grouping patients with similar patterns of comorbidity. Comorbidities for all CMC were gathered from all the diagnoses registered and updated from 2014 to 2016. Diagnoses were coded using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Clinical Classification Software (CCS) [29]. From a list of 184 relevant CCS, we grouped them into disease categories in order to facilitate information management. For each different CCS, it was only counted once in each individual. To obtain consistent and clinically relevant patterns of association, and to avoid spurious relationships that could bias the results, we considered only diagnosis categories with a prevalence of > 1%. Finally, 57 disease categories were included, covering 90.6% of all diseases (see Additional file 2).

For the exposure variable, the SEP of each child was measured based on economic information relating to one of their parents or guardians, including: employment status, individual income, and the receipt of welfare assistance. SEP was grouped into three categories: low (no member of the household employed or in receipt of welfare support from the government, and an income <€18,000/year, considered at risk of poverty [30]); middle (guardian employed with an income <€18,000); and high (guardian employment, with income >€18,000).

Age was categorised based on clinical criteria for children’s growth (0–1, 2–4, 5–11, 12–14) and used as the covariate, and sex was used as the stratification variable.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis of both the CMC and non-CMC populations was carried out. Bivariate analysis was conducted to determine differences between CMC and non-CMC groups according to sex, age, SEP, and GMA; proportion tests and Chi-square tests (for categorical variables) and a T-test or Mann–Whitney U (for continous variables) test were carried out depending on variable distribution.

Next, we used latent class analysis (LCA) [31] to classify CMC into patterns of comorbidity according to their distribution of disease categories. The objective of LCA is to classify individuals from an apparently heterogeneous population into more homogenous subgroups (latent classes) based on a number of observed indicators, in this case, the 57 disease categories.

To determine the optimal number of latent classes to fit the data, we used the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC). An overall χ2 statistic was used to assess the model [32]. We compared candidate models and applied substantive interpretability and clinical judgement (i.e., do the classes defined by a given model possess a clinical significance or meaning?). After selecting a latent class model, we assigned each participant to his or her ‘best-fit’ class, meaning the class for which the participant had the highest computed probability of membership.

Subsequently we describle age, SEP, and GMA distribution in each class found in the LCA analysis by sex. Bivarate analysis was conducted to determine differences between boys and girls – a proportion test and Chi-square test, and T-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests were carried out. Finally, regression logistic models were used to examine the relationship between class membership and SEP with confidence intervals at 95% (CI95%) and their p-values.

All the analyses were carried out for boys and girls, separately. For all tests, the accepted significance level was 0.05 and adjusted by age. LCA was performed using the poLCA package [33] and R statistical software, version 3.3.1 [34], for conducting all analyses.

Results

Characteristics of the CMC population

The main characteristics of the CMC (0.5%) and non-CMC (99.5%) populations are described in Table 1. Both populations contained a higher proportion of boys (CMC 58.5% versus non-CMC 51.1%) than girls.

Almost a quarter of CMC were in the two first years of life (25.2% boys and 24.4% girls); compared with the non-CMC population; this rate was 2.2 times higher in boys and 2.1 times higher in girls. Approximately 50% of CMC of both sexes were aged under five, compared with around 30% of non-CMC; the rate was 69.7% higher in boys and 65.7% higher in girls (Table 1).

In terms of SEP, 71.1% of CMC (6.6% of non-CMC) had at least one parent with an annual income of less than €18,000 (low and middle SEP). Low SEP had a prevalence of 12.8% in the CMC group (12.7% in boys and 12.9% in girls) compared to 8.8% in non-CMC in both boys and girls; it is 44.5% higher in boys and 46.6% higher in girls in CMC than in the non-CMC group.

Comorbidity classes of CMC

The smallest BIC and AIC values were obtained for the 4-class and 5-class candidate models. (see Additional file 3 for statistical values); after applying clinical criteria and χ2 value, we selected the 4-class model. The four classes were labelled based on which conditions exhibited more prevalence: oncology, neurodevelopment, congenital and perinatal, and respiratory.

Prevalences of all disease categories in each class are summarised in Additional file 4. Upper respiratory disease, infection, gastrointestinal disorders, fractures and injuries, and ear, eye, and skin disorders were highly present in all classes.

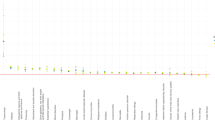

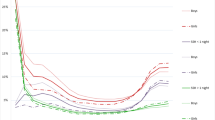

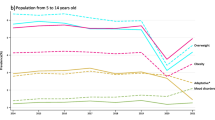

The characteristics of the classes are summarised in Table 2 and their distribution during childhood is shown in Fig. 1. The SEP and age distribution of each obtained class is summarised in Table 2 and Fig. 1. Figures 2a,b,c,d display the most prevalent diseases (> 20%) in each of the four classes.

a Most prevalent diseases (> 20%) in the oncology class. b Most prevalent diseases (> 20%) in the neurodevelopment class. Abreviations: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis. Other hereditary and degenerative nervous system conditions. c Most prevalent diseases (> 20%) in the congenital and perinatal class. Abreviations: Short gestation; low birth weight; and foetal growth retardation. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis. d Most prevalent diseases (> 20%) in the respiratory class. Abreviations: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis

Oncology class (Fig. 2a): includes 2141 children (36.0% of the CMC). Distribution was highest up to five years. There was a high proportion of oncological and related diseases: malignant cancer (23.7% boys, 24.7% girls), leukaemia (12.3% boys, 10.8% girls), cancer of the brain and nervous system (6.4% boys, 7.1% girls), and haematological disorders (36.1% boys, 35.0% girls).

Neurodevelopment class (Fig. 2b): includes 818 children (13.7% of the CMC). Distribution is fairly constant from 3 years and aupwards. Among the most prevalent diseases were developmental disorders (72.9% boys, 71.0% girls), other nervous system disorders (65.1% boys, 63.7% girls), epilepsy and convulsions (57.1% boys and 61.8% girls), and paralysis (37.7% boys and 39.1% girls).

Congenital and perinatal class (Fig. 2c): includes 1177 children (19.8% of the CMC). Distribution is mainly up to 4 years old. Perinatal trauma (84.1% boys, 74.7% girls), cardiac and circulatory congenital anomalies (43.9% boys, 43.2% girls), short gestation, low birth weight, and foetal growth retardation (38.3% boys, 39.7% girls), and other congenital anomalies (36.8% boys, 35.2% girls) were the most frequent diseases.

Respiratory class (Fig. 2d): included 1814 (30.5% of the CMC). It shows an accumulation of individuals aged between years 1 and 6. The most prominent diseases were chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis (64.2% boys, 62.1% girls), respiratory failure, insufficiency and arrest (54.7% boys, 53.6% girls), and asthma (53.7% boys, 47.4% girls).

SEP inequalities

SEP inequalities in the four clusters are displayed in Table 2 and Fig. 3. There were SEP inequalities in all clusters, for both sexes. From higher to lower OR in one of both sexes, neurodevelopment class showed an association with low SEP ([OR, 2.3; CI95%, 1.7–3.1 in boys] and [OR, 1.8; CI95%, 1.2–2.6 in girls]) compared to the high SEP category, congenital and perinatal class ([OR, 2.1; CI95%, 1.5–2.8 in girls]) and [OR, 1.7; CI95%, 1.3–2.3 in boys]), followed by respiratory class ([OR, 2.0; CI95%, 1.6–2.6 in girls] and [OR, 2.0; CI95%, 1.7–2.5 in boys]), and finally the oncology class ([OR, 2.0; CI95%, 1.7–2.5 in girls] and [OR, 1.9; CI95%, 1.6–2.3 in boys]).

Discussion

Four different comorbidity classes among the CMC were identified. All of them showed SEP inequalities, therefore the more disadvantaged children represent a higher proportion of the CMC group. In both populations (CMC and non-CMC) and sexes, > 60% of children were low and middle SEP. This finding highlights the fact that children are subject to inequalities from the very beginning of their lives [35].

In this study, all CMC classes shared common diseases – specifically gastrointestinal disorders, respiratory diseases, and trauma – as in other population studies [20, 21]. These diseases account for the major causes of hospitalisation rates together with congenital anomalies, and cardiovascular and oncological diseases [7, 21].

All classes had a higher proportion of boys, up to 56%. This result is consistent with the highest vulnerability in boys aged up to five years; male foetuses mature slower than female foetuses do and, after birth, males experience more perinatal issues [36]. This also coincides with the maximum prevalence of the congenital and perinatal, and respiratory classes (99.1 and 76.1%, respectively).

The oncology class contained 36.0% of all CMC and was predominated by individuals aged up to 5 years. Their characteristics were more heterogeneous and showed a higher comorbidity profile. Although this class included almost all the individuals with malignancies, individuals with mental health or endocrine disorders were also highly represented. This pattern is consistent with other studies that emphasise that when a CMC matures he or she could develop more than one comorbidity as a result of their main pathology [20], and often this new comorbidities are related to mental disorders [37].

The neurodevelopment class includes two related types of diseases: nervous system disorders such as paralysis and epilepsy, and congenital, perinatal, and degenerative anomalies. Their prevalence remains steady as the child grows older; they have a chronic, cumulative profile due to the difficulty of healing, and they may be precursors of future complications in other systems [38]. The aetiology of nervous system anomalies may be related to SEP inequalities, such as exposure to certain environmental factors [39], maternal stress during pregnancy, or adverse gestational and delivery outcomes [40, 41]. All these events occur in the prenatal and perinatal period but their impact may emerge at a later stage. This class showed the highest median GMA, since the prognosis and development of the pathology entail a high risk and large use of healthcare resources.

The congenital and perinatal disease class comprises mainly adverse birth outcomes and congenital anomalies in diverse body systems, especially heart defects in concordance with the principal incidence of congenital anomalies in other populations [42]. The maximum prevalance of the congenital and perinatal class was observed in the first two years of life, due to the congenital aetiology. In this short time, SEP influences the child mainly via the mother: maternal behaviour during pregnancy has been identified as a risk factor [43,44,45]. It should also be noted that advances in perinatal care have increased the likelihood of survival for extremely preterm infants, who are mostly included in this class.

The respiratory class includes mainly pulmonary diseases. In accordance with the natural development of most respiratory diseases, its prevalence was highest in the mid-age range, and it accounted for 30% of all the CMC. Risk factors known to be related to SEP inequalities in this class are: exposure to air pollution [46], in utero exposure to tobacco [47], maternal stress [45], and low weight at birth and prematurity [48].

The age distribution of each class showed the ages of maximum expression of each of the patterns (see Fig. 1). It should be noted that diseases are not static, and prognosis may mean that individuals move from class to class.

All CMC classes showed SEP inequalities, thus corroborating the previous analyses carried out in Catalonia [18, 19] and elsewhere [7, 16]. SEP inequalities were similar across the four classes, which highlights the lack of economic support in accessing the best development and care that these children and their family experience. Our study denotes that family’s SEP is related to CMC. This fact could impact on their development and hindering these children from achieving their potential. Having to care for CMC may also further negatively affect families’ economic position and health [12, 14, 15] and may, in turn, affect the CMC. In contrast, families with more economic resources are able to provide more active stimulation, alternative treatments, and an environment that is safer and more conducive to maintaining good health in childhood. This phenomenon has been termed the “buffering effect of income” in chronic conditions [38]. On the other hand, these results denote that inequities are already established in the first years of life, suggesting that there is a pattern of causality as indicated by different studies of highly disabling diseases [16]. The idea that, since conception, SEP inequalities are an important factor determining the developmental origin of different diseases, is increasingly gaining more evidence, establishing that the mother and the family environment are key to the production of disease [49]. Ensuring this pattern in all diseases is challenging, but our results, especially in regard to the youngest CMC, cannot be explained by reverse causality alone. This indicates that the issue warrants further research. According to different experts on CMC [11], other social determinants of health such as ethnicity, immigration status, or geographical isolation, influence CMC’s health outcomes. Our data does not allow for deeper insights on ethnicity; this should be explored further in future research as some studies have identified it as a factor having more influence than SEP [7, 17].

Study strengths and limitations

Identifying CMC at a population level is not straightforward. There is no specific agreed criteria for definingthe CMC population, and all of the proposed criteria have present limitations. The GMA, like other classification systems, was originally created for the whole population (children and adults). Nevertheless, Clinical Risk Groups based on the same principle and have been successfully used to identify CMC populations [2, 3, 50, 51]. Furthermore, clinical diagnoses across the historical healthcare contacts have been considered as it is recommend [28], providing a more realistic approach to the health status of the children.

Because of the limited data available on income, we were unable to obtain a more detailed segmentation of the SEP variable. This was especially true in the case of the high SEP category, which included a wide range of income levels. Further segmentation of this category would have given a more accurate approximation of the SEP gradient. However, parental income is the SEP indicator that most directly measures the family’s material resources. With other indicators, such as labour, income has a ‘dose-response’ association with health [52]. Some studies have used maternal education or an ecological deprivation index as a proxy for SEP [7, 16, 17]; the present study goes further by using population-based individual income data, which is more directly related to the material resources.

The health status data is based on the use of public healthcare resources, since data from private healthcare providers was not available. Even so, the bias is presumably very low, as CMC patients require highly specialised care and, for this reason, are mainly treated in the public healthcare system.

The main strength of this population-based study is the use of robust individual administrative data, like similar studies and databases [2, 6, 7]. Another advantage is that it includes all the children in Catalonia and thus provides a realistic view of the current health status of the population beyond hospital-based care. Hospital-based studies do not address outpatient utilisation of services and do not reflect the highest-risk patients, as they are treated in specialised units; meanwhile, our study sheds light on all the comorbidities adjacent to the CMC population with a more chronic profile.

Conclusion

Our findings have demonstrated the existence of different patterns of comorbidities in CMC and a high proportion of lower socioeconomic children in all classes. This result could benefit CMC management by enabling the creation of more efficient multidisciplinary teams according to each comorbidity class and informing a holistic perspective taking into account the socioeconomic vulnerability this population faces.

Daily life for CMC and their families is not only complex from the perspective of healthcare; every area of life is complex. Child health and family health are two sides of the same coin. Introducing policies to support both their health and financial situation will have implications beyond children’s health itself.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to the presence of personal information that could compromise research participants’ privacy. The anonymised and unidentified data will be accessible to the research staff of the research centres accredited by the Research Centres of Catalonia (CERCA) institution, SISCAT agents, and public university research centres, as well as the same health administration.

Abbreviations

- CMC:

-

Children with medical complexity

- SEP:

-

Socioeconomic position

- Catalan acronym GMA:

-

The Adjusted Morbidity Groups

- CHSS:

-

Catalan Health Surveillance System

- CRG:

-

Clinical Risk Group

- CCS:

-

Clinical Classification Software

- LCA:

-

Latent Class Analysis

- BIC:

-

Bayesian Information Criterion

- AIC:

-

Akaike’s Information Criterion

References

Simon TD, Mahant S, Cohen E. Pediatric hospital medicine and children with medical complexity: past, present, and future. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2012;42:113–9.

Neff JM, Sharp VL, Muldoon J, Graham J, Popalisky J, Gay JC. Identifying and classifying children with chronic conditions using administrative data with the clinical risk group classification system. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2:71–9.

Cohen E, Berry JG, Camacho X, Anderson G, Wodchis W, Guttmann A. Patterns and costs of health care use of children with medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e1463.

Burns KH, Casey PH, Lyle RE, Mac BT, Fussell JJ, Robbins JM. Increasing prevalence of medically complex children in US hospitals. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):638–46.

Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, Berry JG, Bhagat SKM, Simon TD, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127:529–38.

Fraser LK, Parslow R. Children with life-limiting conditions in paediatric intensive care units: a national cohort, data linkage study. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103:540–7.

Fraser LK, Miller M, Hain R, Norman P, Aldridge J, McKinney PA, et al. Rising national prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in England. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e923–9.

Rennick JE, Childerhose JE. Redefining success in the PICU: new patient populations shift targets of care. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e289–91.

Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington state, 1980-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 2):205–9.

Van Der Lee JH, Mokkink LB, Grootenhuis MA, Heymans HS, Offringa M. Definitions and measurement of chronic health conditions in childhood: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;297:2741–51.

Barnert ES, Coller RJ, Nelson BB, Thompson LR, Chan V, Padilla C, et al. Experts' perspectives toward a population health approach for children with medical complexity. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:672–7.

Thomson J, Shah SS, Simmons JM, Sauers-Ford HS, Brunswick S, Hall D, et al. Financial and social hardships in families of children with medical complexity. J Pediatr. 2016;172:187–93 e1.

Seltzer RR, Henderson CM, Boss RD. Medical foster care: what happens when children with medical complexity cannot be cared for by their families? Pediatr Res. 2016;79:191–6.

Arthur JD, Gupta D. “You can carry the torch now”: a qualitative analysis of parents’ experiences caring for a child with trisomy 13 or 18. HEC Forum. 2017;29:223–40.

Woodgate RL, Edwards M, Ripat JD, Borton B, Rempel G. Intense parenting: a qualitative study detailing the experiences of parenting children with complex care needs. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:1–15.

Spencer NJ, Blackburn CM, Read JM. Disabling chronic conditions in childhood and socioeconomic disadvantage: a systematic review and meta-analyses of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007062.

Parslow RC, Tasker RC, Draper ES, Parry GJ, Jones S, Chater T, et al. Epidemiology of critically ill children in England and Wales: incidence, mortality, deprivation and ethnicity. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:210–5.

Observatori del Sistema de Salut de Catalunya. Desigualtats socioeconòmiques en la salut i la utilització de serveis sanitaris públics en la població de Catalunya. Barcelona (Spain): Agència de Qualitat i Avaluació Sanitàries de Catalunya. Departament de Salut. Generalitat de Catalunya; 2017. [http://observatorisalut.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/observatorisalut/ossc_crisi_salut/Fitxers_crisi/Salut_crisi_informe_2016.pdf]. Accessed on date 10 Oct 2019.

García-Altés A, Ruiz-Muñoz D, Colls C, Mias M, Martín BN. Socioeconomic inequalities in health and the use of healthcare services in Catalonia: analysis of the individual data of 7.5 million residents. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018;72:871–9.

Crow SS, Undavalli C, Warner DO, Katusic SK, Kandel P, Murphy SL, et al. Epidemiology of pediatric critical illness in a population-based birth cohort in Olmsted county, MN. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18:e137–45.

Gold JM, Hall M, Shah SS, Thomson J, Subramony A, Mahant S, et al. Long length of hospital stay in children with medical complexity. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:750–6.

Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380:37–43.

Hesketh KR, Fagg J, Muniz-Terrera G, Bedford H, Law C, Hope S. Co-occurrence and clustering of health conditions at age 11: cross-sectional findings from the millennium cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012919.

Monterde D, Vela E, Clèries M. Los grupos de morbilidad ajustados: nuevo agrupador de morbilidad poblacional de utilidad en el ámbito de la atención primaria. Aten Primaria. 2016;48:674–82.

Dueñas-Espín I, Vela E, Pauws S, Bescos C, Cano I, Cleries M, et al. Proposals for enhanced health risk assessment and stratification in an integrated care scenario. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010301.

Cerezo J, Arias C. Population stratification: A fundamental instrument used for population health management in Spain. In: Good Practice Brief. Regional Office of Europe. World Health Organization (WHO); 2018. [http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/364191/gpb-population-stratification-spain.pdf?ua=1]. Accessed on date 10 Oct 2019.

Neff JM, Sharp VL, Muldoon J, Graham J, Myers K. Profile of medical charges for children by health status group and severity level in a Washington state health plan. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:73–89.

Berry JG, Hall M, Cohen E, O’Neill M, Feudtner C. Ways to identify children with medical complexity and the importance of why. J Pediatr. 2015;167:229–37.

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project – HCUP A Federal-State-Industry Partnership in Health Data Clinical Classifications Software (CCS); 2015. [http://www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup]. Accessed on date 10 Nov 2017.

Idescat. Enquesta de condicions de vida. Llindar de risc de pobresa segons la composició de la llar. Barcelona (Spain): Idescat-Institut d'Estadística de Catalunya. [Internet]. [https://www.idescat.cat/pub/?id=ecv&n=7623]. Accessed on date 04 May 2019.

Hagenaars JA, McCutcheon AL. Applied latent class analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

Kongsted A, Nielsen AM. Latent class analysis in health research. J Physiother. 2017;63:55–8.

Linzer D, Lewis J. Package “poLCA”. Polytomous variable Latent Class Analysis. August 29, 2016. In: The Comprehensive R Archive Network. The R Project for Statistical Computing [Internet]. [https://cran.r-project.org/https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/poLCA/poLCA.pdf]. Accessed on date 04 May 2019.

RStudio. Open source & professional software for data science teams [Internet]. Boston, MA: RS Studio [https://rstudio.com]. Accessed on date 18 Apr 2018.

Instituto UAM-UNICEF de Necesidades y Derechos de la Infancia y la Adolescencia (IUNDIA). Pobreza y exclusión social de la infancia en España. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social; 2009. [https://observatoriodelainfancia.vpsocial.gob.es/productos/pdf/pobrezaExcInfEspana.pdf]. Accessed on date 04 Apr 2020.

DiPietro JA, Voegtline KM. The gestational foundation of sex differences in development and vulnerability. Neuroscience. 2017;342:4–20.

Nelson LP, Gold JI. Posttraumatic stress disorder in children and their parents following admission to the pediatric intensive care unit: a review. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:338–47.

Case A, Lubotsky D, Paxson C. Economic status and health in childhood: the origin of the gradient. Am Econ Rev. 2002;92:1308–34.

González-Alzaga B, Lacasaña M, Aguilar-Garduño C, Rodríguez-Barranco M, Ballester F, Rebagliato M, et al. A systematic review of neurodevelopmental effects of prenatal and postnatal organophosphate pesticide exposure. Toxicol Lett. 2014;230:104–21.

Kelly R, Ramaiah SM, Sheridan H, Cruickshank H, Rudnicka M, Kissack C, et al. Dose-dependent relationship between acidosis at birth and likelihood of death or cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018;103:F567–72.

Himmelmann K, Ahlin K, Jacobsson B, Cans C, Thorsen P. Risk factors for cerebral palsy in children born at term. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:1070–81.

Mai CT, Riehle-Colarusso T, O’Halloran A, Cragan JD, Olney RS, Lin A, et al. Selected birth defects data from population-based birth defects surveillance programs in the United States, 2005-2009: featuring critical congenital heart defects targeted for pulse oximetry screening. Birth Defects Res Part A - Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94:970–83.

Stothard KJ, Tennant PWG, Bell R, Rankin J. Maternal overweight and obesity and the risk of congenital anomalies. JAMA. 2009;301:636.

Martínez-Frías ML, Bermejo E, Rodríguez-Pinilla E, Frías JL. Risk for congenital anomalies associated with different sporadic and daily doses of alcohol consumption during pregnancy: a case-control study. Birth Defects Res Part A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70:194–200.

Wright RJ, Visness CM, Calatroni A, Grayson MH, Gold DR, Sandel MT, et al. Prenatal maternal stress and cord blood innate and adaptive cytokine responses in an inner-city cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:25–33.

Li S, Williams G, Jalaludin B, Baker P. Panel studies of air pollution on children’s lung function and respiratory symptoms: a literature review. J Asthma. 2012;49:895–910.

McEvoy CT, Spindel ER. Pulmonary effects of maternal smoking on the fetus and child: effects on lung development, respiratory morbidities, and life long lung health. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2017;21:27–33.

Skromme K, Vollsæter M, Øymar K, Markestad T, Halvorsen T. Respiratory morbidity through the first decade of life in a national cohort of children born extremely preterm. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18:102.

Wallack L, Thornburg K. Developmental origins, epigenetics, and equity: moving upstream. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:935–40.

Loh W, Tang M. The epidemiology of food allergy in the global context. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(9):2043.

Berry JG, Hall M, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Agrawal R, et al. Inpatient growth and resource use in 28 children’s hospitals: a longitudinal, multi-institutional study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:170–7.

Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey SG. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:7–12.

Acknowledgements

We thank Emili Vela (from the Catalan Health Service) for generously sharing his knowledge of GMA; Juan José García García, head of the paediatric service at Sant Joan de Déu Barcelona Hospital, for his insights regarding the data and the results; Elisenda Martinez, for her support in data analysis; and Cristina Colls and Dolores Ruiz Muñoz, for their assistance and professional knowledge.

Funding

This work was supported by the Industrial Doctorates Plan of the Catalan Government. The founder had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NC had full access to all the data in the study and vouches for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: AGA. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: NC and ADB. Drafting of the manuscript: NC. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: NC and AGA. Study supervision: All authors. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Authors’ information

This work has been conducted within the framework of the PhD in Biomedics of the University Pompeu Fabra.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None declared.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Adjusted morbidity groups. Description of data: Details of the adjusted morbidity groups construction.

Additional file 2.

List of the Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-MC. included in each disease category (covering 90.6% of all the disease events). Description of data: Clinical codes included in each disease category.

Additional file 3.

LCA statistics. Description of data: LCA statistics for all the models used. It included Chisq Chi_square goodness of fit, Bayesian Information Criterion, Akaike’s Information Criterion, Log_likelihood, Consistent Alkaike’s Information Criterion and Likelihood Ratio chi-square.

Additional file 4.

Prevalences of all disease categories by sex for each comorbidity class among the CMC in Catalonia, 2016. Description of data: Prevalences of all the disease categories for each of the comorbidity classes obtained in the LCA. This data shows the frequencies and percentages of each disease category by sex for each of the classes obtained.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Carrilero, N., Dalmau-Bueno, A. & García-Altés, A. Comorbidity patterns and socioeconomic inequalities in children under 15 with medical complexity: a population-based study. BMC Pediatr 20, 358 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02253-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02253-z