Abstract

Background

Adolescents with chronic illness (CI) and parents of a child with CI are at risk for psychosocial problems. Psychosocial group interventions may prevent these problems. With the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy, active coping strategies can be learned. Offering an intervention online eliminates logistic barriers (travel time and distance) and improves accessibility for participants. Aim of this study is to examine the effectiveness of two cognitive-behavioral based online group interventions, one for adolescents and one for parents: Op Koers Online. The approach is generic, which makes it easier for patients with rare illnesses to participate.

Methods/design

This study conducts two separate multicenter randomized controlled trials. Participants are adolescents (12 to 18 years of age) with CI and parents of children (0 to 18 years of age) with CI. Participants are randomly allocated to the intervention group or the waitlist control group. Outcomes are measured with standardized questionnaires at baseline, after 8 (adolescents) or 6 (parents) weeks of treatment, and at 6- and 12-month follow-up period. Primary outcomes are psychosocial functioning (emotional and behavioral problems) and disease-related coping skills. Secondary outcomes for adolescents are self-esteem and quality of life. Secondary outcomes for parents are impact of the illness on family functioning, parental distress, social involvement and illness cognitions. The analyses will be performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Primary and secondary outcomes will be assessed with linear mixed model analyses using SPSS.

Discussion

These randomized controlled trials evaluate the effectiveness of two online group interventions improving psychosocial functioning in adolescents with CI and parents of children with CI. If proven effective, the intervention will be optimized and implemented in clinical practice.

Trial registration

ISRCTN ISRCTN83623452. Registered 30 November 2017. Retrospectively registered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Children and adolescents with a chronic illness (CI) have to face difficulties related to their illness, such as hospitalization, the use of medication, restrictions in activities and stressors related to the course of the illness and the future [1,2,3]. In the Netherlands, 14% of children and adolescents is growing up with a CI (for example diabetes, asthma or Cystic Fibrosis) [4]. Growing up with a CI influences psychosocial wellbeing and the development of cognitive and social skills [2, 5,6,7]. Especially during adolescence, with the formation of identity, self-image and self-esteem, a CI constitutes a major challenge [8, 9].

Research shows that pediatric CI influences psychosocial wellbeing in parents as well [10, 11]. Parents are predominantly responsible for managing the child’s illness. They are confronted with stressors about their child’s health as well as logistical and practical factors such as managing daily routines, relationships with other family members, the balance between family and work and possible financial problems [11, 12]. Therefore, parents are at risk for sorrow and psychosocial distress [10, 12]. Parents who face stress are less able to manage the child’s illness effectively [11]. To prevent and/or to reduce psychosocial problems in parents as well as adolescents, interventions focusing on how to cope with stressors caused by the CI are needed [13].

The disability-stress-coping model states that stressors related to the illness and psychosocial adjustment of children and mothers are moderated by coping strategies and cognitive appraisals [14]. Moreover, research has shown that effective use of coping skills increases adolescents’ medical compliance, improves their psychosocial functioning [2, 15,16,17,18,19,20] and reduces distress and anxiety in parents [21, 22]. Results on the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral based psychosocial group interventions to learn children and adolescents how to use more effective coping skills are promising [23,24,25]. Research shows that including parents in a psychosocial intervention for children with chronic pain is effective in reducing child’s pain [22]. There is some evidence of effectiveness of interventions focusing on parents themselves: coping support interventions reduce parental psychological problems during acute hospitalization [21] and problem solving therapy for parents improves parental mental health [22]. However, little is known about the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral based psychosocial group interventions for parents focusing on themselves.

In 2003, the face-to-face cognitive-behavioral based group intervention Op Koers (English: On Track) for children and adolescent with CI was developed in the Emma Children’s Hospital (Academic Medical Center Amsterdam). Over the years, the program was expanded with courses for siblings and parents, and a similar Op Koers program for pediatric oncology patients. Goal of Op Koers is to prevent and/or to reduce psychosocial problems of participants by teaching active coping skills with the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques [26]. The approach is generic, which means that patients with every type of CI can participate. This has the benefit of giving more patients at once the opportunity to participate and to include patients with rare illnesses in group interventions [23, 26]. Sharing experiences with others in a similar situation had been associated with a decrease of distress and improvement of social health [23, 27,28,29] and is therefore an important part of Op Koers. There have been different studies about this intervention program [26, 30, 31]. Part of the research has been an RCT on the efficacy of Op Koers for children and adolescents with CI. This study showed positive short- (half year) and long-term (one year) effects on the use of coping skills and psychosocial functioning. For children and adolescents, there was an additional positive effect of parental involvement, especially on long-term and in social-emotional vulnerable children [32,33,34].

The face-to-face setting of Op Koers requires participants to regularly come to the hospital, in addition to other medical appointments. An online intervention eliminates logistical barriers such as travel time and distance [35, 36] which makes the intervention more easily accessible [35, 37, 38]. Participating in an intervention online connects to the digital environment in which people live nowadays. Besides, an online environment without use of a webcam increases anonymity: appearance plays no role and this might make it easier to talk about problems [38,39,40]. Therefore, Op Koers was translated into an online intervention: Op Koers Online.

First, the intervention for survivors of childhood cancer was developed. A pilot study on the feasibility of Op Koers Online Oncology for adolescent survivors showed promising results [39]. The intervention was optimized based on feedback from participants and course leaders (for example: expanding the sessions from six to eight). After that, Op Koers Online for adolescents with CI was developed. Similar to the face-to-face intervention, goal is to prevent and/or reduce psychosocial problems by teaching the use of active coping skills with CBT techniques. Sharing experiences with other chronically ill adolescents is an important part of the intervention. First pilot results on the feasibility and potential effectiveness of Op Koers Online for adolescents with CI are promising (Douma et al.: Feasibility and effectiveness of an online cognitive-behavioral based group intervention for adolescents with chronic illness, submitted).

For parents, most existing interventions focus on the child’s functioning [13, 22]. The same applies to Op Koers face-to-face for parents, where participating parents learn what their child learns and how to support their child in implementing coping skills in daily life [32, 34]. However, research suggests the need of emotional, informational and peer support for parents [41, 42]. For the development of Op Koers Online for parents, the Emma Children’s Hospital (Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam) conducted a survey among parents on their specific wishes and needs. The need for an intervention focusing on parental functioning instead of focusing only on the child emerged from the survey. Based on the results of this survey, Op Koers Online for parents of children with CI was designed.

This paper describes the rationale and the design of two separate multi-center randomized controlled trails aimed to assess the extent to which Op Koers Online is effective in preventing and/or reducing psychosocial problems (emotional/behavioral problems and quality of life) and improving the use of disease-related coping skills in adolescents with CI (12–18 years) and in parents of children and adolescents (0–18 years) with CI.

Methods

Procedure

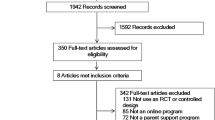

Figure 1 shows the different phases of the study procedure. There is one coordinating hospital (Emma Children’s Hospital, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam) and eight participating hospitals across the Netherlands (one academic, seven non-academic). The researcher of the coordinating hospital coordinates overall recruitment and administers inclusion of all participants. Local recruitment is coordinated by local investigators of each participating hospital. Adolescents and parents from the outpatient clinics from the nine hospitals receive an information letter from their pediatrician. To improve inclusion of adolescents and parents for the study, we asked permission from the Medical Ethical Committee (METC) to make the procedure open accessible and permission was obtained. Besides the information letters, pamphlets are available in the participating hospitals and other interested hospitals (approached randomly by the coordinating researcher). Recruitment is done via internet (websites and social media) and via patient associations.

Interested adolescents and parents are asked to return the application form added to the pamphlet or to send an e-mail. A telephonic interview is used to screen inclusion criteria, discuss the information about the intervention and the study and to discuss the informed consent. Potential participants can ask questions and get one week to overthink participation. When willing to participate, an informed consent form is sent to the participant to sign and return. As soon as the informed consent form is signed by the researcher as well, the researcher registers the participant online (http://www.opkoersonline.nl). Participants receive an e-mail with a link to create personal login codes, with which they can login to the secured website.

Every registered participant is in the virtual ‘waiting room’ until randomization. They are informed about the result of the randomization by e-mail. When randomized in the intervention group, the researcher calls the participant to determine the dates of the intervention. At four time-points, all participants and parents of participating adolescents are invited to complete questionnaires via an e-mail with a personal link to the questionnaire. Total duration time for completion is estimated at 45 min for adolescents and parents and 30 min for the parents of participating adolescents. After completing all assessments, participants receive a financial reward (€20 voucher for an online book/game store).

Interventions

The interventions consist of eight (for adolescents) or six (for parents) weekly sessions of 90 min, which take place in a secured chatroom (Fig. 2) with groups of three to six participants. The interventions are guided by two course leaders, one specialized health-care psychologist and one co-therapist (mostly a psychological assistant), who are trained and use a detailed manual. The training consists of three parts: 1) teaching the main principles of cognitive-behavioral group therapy and the history of the Op Koers courses, 2) giving more specific information on the procedures and goals related to the different sessions using examples from former chat sessions and the extensive manual for psychologists, 3) practicing in online subgroups. To ensure treatment integrity, the researcher of the coordinating hospital randomly checks the chats of participating hospitals with the manual. All participants and course leaders log on at the same time every week. Participants can log on to the homework site to view the intervention material (information sheets and videos), submit homework before every session and view additional information. Four months after the last session, there is a booster session.

Central in the interventions is the Thinking-Feeling-Doing model (TFD model). With this model, course leaders teach participants the relationship between what people think, feel and how they act, and how they can influence their thoughts feelings and behaviors. Every intervention group starts the first session with an extensive acquaintance (questions such as: who are you, what do you do, which illness do you/does your child have, what are your expectations of the course, etc.) to create a feeling of safety within the group and in the chat box. No webcams are used in the interventions.

‘Op Koers Online’ for adolescents

The aim of the intervention for adolescents (12 to 18 years) is to prevent and/or to reduce psychosocial problems, by teaching the use of active coping strategies. These strategies are taught by recognizing negative thoughts and transforming them into more positive and proactive ones, with the use of CBT techniques (TFD-model) [25, 43, 44].

Learning goals of the adolescent intervention are increasing the use of five coping skills taught with the CBT techniques (e.g. relaxation, cognitive restructuring and open communication) [43, 45, 46]: 1) information seeking and giving about the illness, 2) use of relaxation during stressful (medical) situations, 3) increase knowledge of self-management and medical compliance, 4) improvement of social competence and 5) positive thinking [26, 34]. See Table 1 for learning goals and corresponding instructions and reinforcement techniques. Each coping skill is taught during one specific session, but elements of the coping skills are also addressed in the subsequent sessions. The skills are taught by psycho-education (e.g. video’s, group discussions), through exercises (e.g. virtual board games) and homework assignments (e.g. practicing relaxation exercise in daily life).

‘Op Koers Online’ for parents

Aim of the intervention for parents is also to prevent and/or to reduce psychosocial problems by teaching the use of active coping strategies. Strategies to help parents focusing on elements they think are important in life, and to act conform these elements, are taught with the use of CBT techniques and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). ACT, part of CBT, is an intervention strategy to learn participants how to accept a new situation (such as: having a child with CI) and to establish new routines. Goal is to increase or create psychological flexibility. This is done with relaxation exercises and reflection which helps participants to remind and recognize what barriers they face in achieving goals and living consistent with their values, and how to adjust behavior in these situations [47,48,49]. There is growing evidence for the effectiveness of ACT [47, 50,51,52].

Learning goals of the parent intervention are increasing the use of five coping skills taught with CBT and ACT techniques: 1) use of relaxation during stressful situations, 2) increase knowledge of self-management and compliance of their child, 3) positive thinking, 4) positive parenting and 5) open communication about the illness and seeking and accepting support. See Table 1 for learning goals and corresponding instructions and reinforcement techniques.

Every session has a subject. However, specific content of each session is determined by parents: what they want to discuss. Subjects are: the parent (e.g. taking care of yourself), the family (e.g. positive parenting), the hospital (e.g. child’s compliance), extended family and friends (e.g. seeking and accepting support), and daily life (e.g. work, school; open communication). Participants are asked to answer questions concerning the subject of the session (for example the following question about the subject ‘the family’: “How does the illness affect your child his/her siblings/you and your (ex-)partner?”) and to react on each other (giving tips, asking questions, sharing experiences). The questions are displayed in the right screen of the chat box. An important part is sharing experiences with other group members and giving and receiving social/emotional support. Compared to the intervention for adolescents, the intervention for parents is less protocolled. There is more room for personal input and (spontaneous) group discussions, and there are less video’s, games and exercises during the sessions.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Adolescents between 12 and 18 years old with CI, and parents of children between 0 and 18 years old with CI are included. The term CI refers to an illness that requires at least six months of continuous medical care, permanent life style changes and continuous behavioral adaptation to the unpredictable course of the illness [4]. Participants (for parents: their child) have to be treated by a pediatric specialist in a pediatric hospital in the Netherlands. Adolescents and parents of participating adolescents should be able to fill out Dutch questionnaires and to follow the chat intervention in Dutch. A computer or tablet with internet connection to enter the website and chat box is necessary. Adolescents and parents with severe learning difficulties are excluded from the intervention. For them, an adapted or individual program might fit better to their individual cognitive needs.

Study design

The current study consists of two separate multi-center randomized controlled trails: one for adolescents and one for parents. Both trials have two conditions: the intervention group (Op Koers Online) and the waitlist control group. An adolescent and a parent can both participate, but this is not required. When both parents want to apply for the study, they can participate separately. Participants assigned to the waitlist control group receive care-as-usual and are not prevented to seek individual psychosocial treatment. If a participant needs psychosocial care, this will be approved. When participants from either the intervention or the control group receive (additional) psychological treatment during the study period, it will be extensively documented and controlled for in the analyses. When the study is finished, participants from the waitlist group have the opportunity to participate in the intervention.

Assessment of outcome measures takes place with online questionnaires at baseline (before randomization; T0), directly after the intervention period (eight weeks for adolescents, six weeks for parents; T1), six months (T2) and twelve months (T3) after baseline. For adolescents participating in the study, one of their parents is asked to complete questionnaires as well.

This study was approved by the METC of the Academic Medical Center Amsterdam and of the eight participating hospitals.

Randomization

With an average of five participants per intervention group, a total of ten intervention groups for both adolescents and parents will be given. Interventions are organized at different time points (in four to six cohorts, dependent on inclusion rates). In each cohort, participants are randomly allocated to the conditions resulting in an equal number of participants in the intervention and waitlist control condition. The randomization is carried out by an independent IT worker from a company for e-health development who administers the website for Op Koers Online, using block randomization software.

Sample size

Earlier studies on the effectiveness of Op Koers and comparable effect studies showed effects of medium size [32, 53]. Based on a design with four repeated measurements and a within subject correlation of .5, 84 adolescents and 84 parents are needed – 42 in each condition – to detect an intervention effect of medium size (d = .05) over time, at a two-sided .05 significance level and 80% power. Taking into account a dropout of 15% over time, 96 adolescents and 96 parents are needed to achieve the intended power.

Outcome measures

Questionnaires

The outcome measures will be assessed by standardized questionnaires with good psychometric qualities and available normative data (Table 2) [26, 54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. To assess participants’ satisfaction with the intervention, content, design and course leaders, participants in the intervention group complete an evaluation questionnaire at the end of the intervention period (T1).

Statistical analyses

Analyses will be performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Primary and secondary outcomes will be assessed with linear mixed model analyses using SPSS. The intervention is qualified as effective if the intervention group improved more over time on one of the primary outcomes than the control group, at a significance level of 0.05 and at small to medium effect size d [0.2–0.5].

Discussion

This paper outlines the study protocol for two multicenter randomized controlled trials on the effects of two cognitive-behavioral based online group interventions: one for adolescents with CI and one for parents of children and adolescents with CI. Earlier studies showed that psychological interventions for children and adolescents with CI, and for parents, can improve psychosocial functioning [22, 23, 32]. Also, studies on effectiveness of online interventions showed promising results [40, 64,65,66]. Online interventions are easily accessible and, when not using a webcam, anonymous [38,39,40]. These factors can increase possibility and willingness from participants to apply for a psychosocial intervention. There is a lack of evidence-based online group interventions for adolescents with CI and for parents. Studies in this field are limited. Therefore, this study is unique in focusing on an online cognitive-behavioral group intervention for these populations.

This study has several strong points. First, participation in the intervention and the study are completely online, which eliminates logistical barriers for participants and therefore keeps drop-out rate low. Second, we include nationwide with focus on a heterogeneous group of different medical chronic diagnosis. This way, is easier to achieve a relatively large study sample, which is beneficial for the statistical power. Third strong point is that participants in the intervention group can be divided over treatment groups independent of the hospital, which benefits the feasibility of the study (it is easier to create intervention groups on different time points, this will overcome drop-out due to availability). Finally, the relatively long term follow-up period promotes stronger long-term results.

Some vulnerabilities have also to be taken into account. First, since recruitment of adolescents for health studies is challenging [67, 68], the intervention for adolescents is at risk for recruitment problems or delay. This could be a threat to the inclusion rates and the statistical power of the study. Second, due to the relatively long follow-up period it is possible that participants will seek other psychosocial support in the study period. This could bias the results. Lastly, since we include nationwide, it is impossible to identify the approached group and to determine non-response.

In conclusion, adolescents with CI and parents of children and adolescents with CI are at risk for developing psychosocial problems. Easily accessible online evidence-based interventions are needed. This study aims to contribute to research on effective interventions for adolescents with CI and parents of children and adolescents with CI by investigating two separate group interventions, for adolescents and for parents. If this study shows significant effects of the interventions on improving psychosocial wellbeing and disease related coping skills in adolescents and/or parents, Op Koers Online will be implemented in clinical practice.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- CBT:

-

Cognitive-behavioral therapy

- CI:

-

Chronic illness

- METC:

-

Medical Ethical Committee

- TFD model:

-

Thinking-Feeling-Doing model

References

de Bruin Esther I, et al. Chronic childhood stress: psychometric properties of the chronic stress questionnaire for children and adolescents (CSQ-CA) in three independent samples. Child Indicators Res. 2017:1-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-017-9478-3.

Compas BE, et al. Coping with chronic illness in childhood and adolescence. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:455–80.

Pinquart M, Shen Y. Behavior problems in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(9):1003–16.

van der Lee JH, et al. Definitions and measurement of chronic health conditions in childhood: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2741–51.

Compas BE, et al. Neurocognitive deficits in children with chronic health conditions. Am Psychol. 2017;72(4):326–38.

Maes M, et al. Loneliness in children and adolescents with chronic physical conditions: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42(6):622–35.

Pinquart M, Teubert D. Academic, physical, and social functioning of children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37(4):376–89.

Chao AM, et al. General life and diabetes-related stressors in early adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Health Care. 2016;30(2):133–42.

Ersig AL, et al. Stressors in teens with type 1 diabetes and their parents: immediate and long-term implications for transition to self-management. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31(4):390–6.

Coughlin MB, Sethares KA. Chronic sorrow in parents of children with a chronic illness or disability: an integrative literature review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;37:108–16.

Cousino MK, Hazen RA. Parenting stress among caregivers of children with chronic illness: a systematic review. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(8):809–28.

Waters DM, et al. Perceptions of stress, coping, and intervention preferences among caregivers of disadvantaged children with asthma. J Child Fam Stud. 2017;26(6):1622–34.

Morawska A, Calam R, Fraser J. Parenting interventions for childhood chronic illness: a review and recommendations for intervention design and delivery. J Child Health Care. 2015;19(1):5–17.

Wallander JL, Varni JW. Effects of pediatric chronic physical disorders on child and family adjustment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1998;39(1):29–46.

Baranyi A, Krauseneck T, Rothenhausler HB. Overall mental distress and health-related quality of life after solid-organ transplantation: results from a retrospective follow-up study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:15.

Blount RL, et al. Evidence-based assessment of coping and stress in pediatric psychology. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33(9):1021–45.

Blumenthal JA, et al. Telephone-based coping skills training for patients awaiting lung transplantation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(3):535–44.

Dean AJ, Walters J, Hall A. A systematic review of interventions to enhance medication adherence in children and adolescents with chronic illness. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(9):717–23.

Yi-Frazier JP, et al. The association of personal resilience with stress, coping, and diabetes outcomes in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: variable- and person-focused approaches. J Health Psychol. 2015;20(9):1196–206.

Norton C, et al. Systematic review: interventions for abdominal pain management in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(2):115–25.

Doupnik SK, et al. Parent coping support interventions during acute pediatric hospitalizations: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):1–16.

Eccleston C, Palermo TM, Fisher E, Law E. Psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Libr. 2012. CD009660.

Plante WA, Lobato D, Engel R. Review of group interventions for pediatric chronic conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26(7):435–53.

Kichler JC, et al. Effectiveness of groups for adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus and their parents. Fam Syst Health. 2013;31(3):280–93.

Clarke GN, DeBar LL. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment for adolescent depression. In: Weisz JR, Kazdin AE, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010. p. 111, 112, 121.

Last BF, et al. Positive effects of a psycho-educational group intervention for children with a chronic disease: first results. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(1):101–12.

Ramchand R, et al. A systematic review of peer-supported interventions for health promotion and disease prevention. Prev Med. 2017;101:156–70.

Treadgold CL, Kuperberg A. Been there, done that, wrote the blog: the choices and challenges of supporting adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4842–9.

Niela-Vilen H, et al. Internet-based peer support for parents: a systematic integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(11):1524–37.

Grootenhuis MA, et al. Evaluation of a psychoeducational intervention for adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21(4):340–5.

Houtzager BA, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF. Supportive groups for siblings of pediatric oncology patients: impact on anxiety. Psychooncology. 2001;10(4):315–24.

Scholten L, et al. Efficacy of psychosocial group intervention for children with chronic illness and their parents. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):e1196–203.

Scholten L, et al. Moderators of the efficacy of a psychosocial group intervention for children with chronic illness and their parents: what works for whom? J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40(2):214–27.

Scholten L, et al. A cognitive behavioral based group intervention for children with a chronic illness and their parents: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:65.

Andrews G, Titov N. Treating people you never see:internet-based treatment of the internalising mental disorders. Aust Health Rev. 2010;34(2):144–7.

Dever Fitzgerald T, et al. Ethical and legal considerations for internet-based psychotherapy. Cogn Behav Ther. 2010;39(3):173–87.

Hedman E, Ljotsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12(6):745–64.

Nicholas J, et al. Help-seeking behaviour and the internet: an investigation amoung Australian adolescents. Aust e-J Adv Mental Health. 2004;3(1):16–23.

Maurice-Stam H, et al. Feasibility of an online cognitive behavioral-based group intervention for adolescents treated for cancer: a pilot study. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2014;32(3):310–21.

van Beugen S, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with chronic somatic conditions: a meta-analytic review. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e88.

Akre C, Suris JC. From controlling to letting go: what are the psychosocial needs of parents of adolescents with a chronic illness? Health Educ Res. 2014;29(5):764–72.

Glenn AD. Using online health communication to manage chronic sorrow: mothers of children with rare diseases speak. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(1):17–24.

Butler AC, et al. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(1):17–31.

Prins PJ, Ollendick TH. Cognitive change and enhanced coping: missing mediational links in cognitive behavior therapy with anxiety-disordered children. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2003;6(2):87–105.

Thompson RD, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for children with comorbid physical illness. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2011;20(2):329–48.

Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):153–66.

Hayes SC, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1–25.

Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy. New York: Guilford Press; 1999.

Pielech M, Vowles KE, Wicksell R. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Pediatric Chronic Pain: Theory and Application. Children (Basel). 2017;4(2):1-12. https://doi.org/10.3390/children4020010.

Powers MB, Vörding MBZVS, Emmelkamp PM. Acceptance and commitment therapy: a meta-analytic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(2):73–80.

Martin S, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy in youth with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and chronic pain and their parents: a pilot study of feasibility and preliminary efficacy. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170(6):1462–70.

Rayner M, et al. Take a breath: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of an online group intervention to reduce traumatic stress in parents of children with a life threatening illness or injury. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:169.

Mendlowitz SL, et al. Cognitive-behavioral group treatments in childhood anxiety disorders: the role of parental involvement. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(10):1223–9.

Spinhoven P, et al. A validation study of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med. 1997;27(2):363–70.

Engelen V, et al. Health related quality of life of Dutch children: psychometric properties of the PedsQL in the Netherlands. BMC Pediatr. 2009;9:68.

Medrano GR, Berlin KS, Hobart Davies W. Utility of the PedsQL family impact module: assessing the psychometric properties in a community sample. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(10):2899–907.

Haverman L, et al. Development and validation of the distress thermometer for parents of a chronically ill child. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1140–6. e2

Evers AW, et al. Beyond unfavorable thinking: the illness cognition questionnaire for chronic diseases. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(6):1026–36.

Verhulst FC, vd Ende J, Koot HM: Manual for the Child Behavior Check List (CBCL/4-18). Rotterdam: Erasmus University/Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Sophia Children’s Hospital; 1996.

Treffers D, et al. Translation and manual of the self-perception profile for adolescents (CBSA). Lisse: Swets and Zeitlinger BV; 2002.

Verhulst F, Van der Ende J, Koot H. Dutch manual for the youth self-report (YSR). Rotterdam: Afdeling Kinder-en Jeugdpsychiatrie, Sophia Kinderziekenhuis/Academisch Ziekenhuis Rotterdam, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam; 1997.

Dam-Baggen V, Kraaimaat F. De Inventarisatielijst Sociale Betrokkenheid (ISB): een zelfbeoordelingslijst om sociale steun te meten. Gedragstherapie. 1992;25(1):27–46.

Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the pediatric quality of life inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39(8):800–12.

Andersson G, et al. Guided internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):288–95.

Elbert NJ, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ehealth interventions in somatic diseases: a systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(4):e110.

van der Zanden R, et al. Effectiveness of an online group course for depression in adolescents and young adults: a randomized trial. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(3):e86.

Lamb J, Puskar KR, Tusaie-Mumford K. Adolescent research recruitment issues and strategies: application in a rural school setting. J Pediatr Nurs. 2001;16(1):43–52.

Nguyen B, et al. Recruitment challenges and recommendations for adolescent obesity trials. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012;48(1):38–43.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the adolescents and parents who currently participate in this study. In addition, we wish to thank the psychologists who carry out the intervention within the participating hospitals. These hospitals are; Emma Children’s Hospital (Amsterdam), VU Medical Centre (Amsterdam), Antonius Hospital (Sneek), Canusius-Wilhelmina Hospital (Nijmegen), DeKinderKliniek (Almere), Deventer Hospital (Deventer), Jeroen Bosch Hospital (Den Bosch) and Treant Group Location Scheper (Emmen). This study is funded by a grant from Fonds NutsOhra (FNO; project number: 100.977).

Funding

The study is funded by Fonds NutsOhra (FNO; project number: 100.977), a social fund for vulnerable groups in Dutch society. FNO had no role in the study design.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable, as this is a protocol manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in the design of the study. MD drafted the manuscript. LS, HMS and MAG edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committees of the Academic Medical Center Amsterdam (reference number 2016_052, NL56656.018.16).

All participants (and their parents when aged < 18) and the researcher signed/will sign informed consent prior to participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Douma, M., Scholten, L., Maurice-Stam, H. et al. Online cognitive-behavioral based group interventions for adolescents with chronic illness and parents: study protocol of two multicenter randomized controlled trials. BMC Pediatr 18, 235 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1216-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1216-6