Abstract

Background

Pediatric nephrology is challenging in developing countries and data on the burden of kidney disease in children is difficult to estimate due to absence of renal registries. We aimed to describe the epidemiology and outcomes of children with renal failure in Cameroon.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 103 medical records of children from 0 to 17 years with renal failure admitted in the Pediatric ward of the Douala General Hospital from 2004 to 2013. Renal failure referred to either acute kidney injury (AKI) or Stage 3–5 chronic kidney disease (CKD). AKI was defined and graded using either the modified RIFLE criteria or the Pediatrics RIFLE criteria, while CKD was graded using the KDIGO criteria. Outcomes of interest were need and access to dialysis and in-hospital mortality. For patients with AKI renal recovery was evaluated at 3 months.

Results

Median age was 84 months (1QR:15–144) with 62.1% males. Frequent clinical symptoms were asthenia, anorexia, 68.8% of participants had anuria. AKI accounted for 84.5% (n = 87) and CKD for 15.5% (n = 16). Chronic glomerulonephritis (9/16) and urologic malformations (7/16) were the causes of CKD and 81.3% were at stage 5. In the AKI subgroup, 86.2% were in stage F, with acute tubular necrosis (n = 50) and pre-renal AKI (n = 31) being the most frequent mechanisms. Sepsis, severe malaria, hypovolemia and herbal concoction were the main etiologies. Eight of 14 (57%) patients with CKD, and 27 of 40 (67.5%) with AKI who required dialysis, accessed it. In-hospital mortality was 50.7% for AKI and 50% for CKD. Of the 25 patients in the AKI group with available data at 3 months, renal recovery was complete in 22, partial in one and 2 were dialysis dependent. Factors associated to mortality were young age (p = 0.001), presence of a coma (p = 0.021), use of herbal concoction (p = 0.024) and acute pulmonary edema (p = 0.011).

Conclusion

Renal failure is severe and carries a high mortality in hospitalized children in Cameroon. Limited access to dialysis and lack of specialized paediatric nephrology services may explain this dismal picture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pediatric nephrology is very challenging and is not a priority in developing countries contrary to developed one [1]. Renal disease in children is common with increase prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) globally and an annual incidence rate of 8% [2,3,4,5]. In addition, acute renal failure, now call acute kidney injury (AKI), is common in children admitted to hospitals, with a pooled incidence estimated at 33.7% [6]. The burden of kidney disease in children in most developing countries including Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is unknown and difficult to estimate due to lack of data on pediatric kidney disease and absence of renal registries in general. Few hospital based studies exist and the reported pattern of renal disease in pediatric population is variable [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. In developing countries the major causes of CKD in children are chronic glomerulonephritis, urologic malformations (posterior urethral valves) and CKD of unknown etiology, while for AKI septicemia, diarrhea, malaria, and hemolytic uremic syndrome are the most frequent causes [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

In Africa and in SSA especially, lack of advanced diagnostic infrastructure treatment facilities, and human resources often leads to inaccurate diagnosis and suboptimal treatment of children with renal diseases. A recent meta-analysis on the outcome of AKI in children in SSA reported that most children presented with severe AKI, with high need for dialysis (66% of them) compared to the pooled world need for dialysis in AKI of 11% [6, 21]. The main reasons were late presentation to hospital, the cost of care, the use of clinical criteria for diagnosis, which appear only at an advanced stage of the disease. Consequently, morbidity and mortality is especially high in SSA where access to dialysis is very limited. Dialysis is not available in all services and only 64% of children with need of dialysis could receive the therapy. Outcome of these children is therefore very poor with a mortality rate estimated at 34%, much higher than the world rates of 13.8% [6, 21,22,23,24].

In Cameroon a country in SSA, nephrology and hemodialysis was expanded in the last decade but more for adults. Pediatrics nephrology is not a priority and the country count only two pediatric nephrologists. General pediatricians manage children, and when necessary they called adult nephrologists for further workup and treatment. Few data exist on the burden of kidney disease amongst adults in Cameroon [25, 26] but data on pediatric renal diseases are inexistent despite the presence of risk factors. We conducted this study with the aim to report the epidemiological profile and outcome of renal failure among hospitalized children in the main tertiary referral hospital of Cameroon and highlighting the challenges of care. This basic data may help health policy makers to plan measures that can improve the condition of children and prevent the disease.

Methods

The study was carried out at the pediatric unit of the Douala general hospital in the littoral region of Cameroon. Douala general hospital is the main one of two tertiary hospitals of the country and the referral hospital for all patients with kidney disease in the region of about 3 million inhabitants. The pediatrics unit has a team of seven general pediatricians that provide care to children mostly referred from others hospital; no nephrologist pediatrician is available and children with kidney disease are followed up by general pediatrician and adult nephrologists when necessary. Hemodialysis is the only renal replacement therapy available in the country. Access to care in Cameroon is not free but rather by payment mostly out of pocket for the majority due to lack of health insurance.

We retrospectively reviewed medical records of children from 0 to 17 years with renal failure admitted in the pediatric ward from 2004 to 2013. On admission in that ward, all children routinely have a complete full blood count, malaria test, serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine. In children with renal abnormalities on admission, kidney test are repeated as needed. An abdominal ultrasound is routinely done for all children with renal impairment. Renal failure referred to either AKI or Stage 3–5 CKD. AKI was defined using either the modified RIFLE criteria (2004–2007) as an absolute increase or decrease of serum creatinine of at least 1.5, or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of more than 25% from baseline (value on admission), or a reduction in urine output of less than 0.5 ml/kg per hour for more than 6 h [27], or using the Pediatrics RIFLE criteria (2008–2012), as urine output,0.5 ml/kg/h for greater than eight hours and /or an estimated creatinine clearance (eCCl) decrease of at least 25%; If previous eGFR was unavailable a baseline eGFR of 100 ml/min/1.73 m2 was assumed [28].

The diagnosis of CKD was based on the eGFR lower than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, in a patients with either previous abnormal creatinine value and/ or urine abnormalities for more than 3 months, associated with one or more of the following: risk factor for CKD (ex: past history of glomerular disease, urologic malformation) presence of bilateral schrunken kidney, hypocalcemia, hyperphosphoremia. [29]

eGFR was determined with the Schwartz formula, using height and serum creatinine [30, 31]. Data collected were: socio demographic information such as age and gender, clinical (temperature, signs and symptom related to renal failure and primary disease, daily urine flow rate, primary diagnosis, laboratory results (kidney test, full blood count) and outcomes (the need and access to dialysis and in-hospital mortality). For patients with AKI renal recovery (decreased of serum creatinine on admission or increase of e CCl) was evaluated at 3 months.

Definitions

Total renal recovery was considered when creatinine or eGFR at 3 months returned to normal or to baseline value for those with CKD. Partial recovery when serum creatinine at 3 months decrease or eGFR increase from the baseline value but did not return to normal and no recovery when at 3 months serum creatinine increase or eGFR decreased compared to admission values or if the patient remain on hemodialysis.

The cause of AKI was taken as the major diagnosis leading to AKI in the child. Sepsis was defined as the presence a systemic inflammatory response (fever >38 °C, high white cell count at presentation) an increased C- reactive protein level due to suspected or proven infection (by positive culture or tissue stain) caused by any pathogen or a clinical syndrome associated with a high probability of infection [32]. Severe malaria was defined as the presence of fever with presence of plasmodium falciparum on peripheral blood film associated with one or more organ dysfunction such as hypotension, coma, need of ventilation, hematologic involvement. Diarrhea was the passage of three or more loose stools per day.

Chronic glomerulonephritis was based either on a history of a documented glomerular disease or the presence of a glomerular syndrome on admission (proteinuria and/or hematuria, hypertension with bilateral small kidney, decrease eGFR, in the absence of identifiable secondary causes. Diagnosis of posterior urethral valves was made on a history of documented urology malformation, and/or on ultrasound scan and micturating cystourethrogram record. Anuria was defined as urine output less than 1 ml/kg/day.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was done with the aid of a software program statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 20. Descriptive statistics used comprised percentages and mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median (IQR). Logistic regression was used to look for factors associated to death. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 103 patients’ records (62% males) were included. The median age was 84 months (IQR: 15–144). The most frequent clinical symptoms were asthenia (97.8%), anorexia (92.3%) oedema (38.8%) and vomiting (37.8%). In total 68.8% (55/103) of participants had anuria. (Table 1).

AKI accounted for 84.5% (n = 87) and 86.2% (75/87) were in stage F, with acute tubular necrosis 57.5% (n = 50/87) and pre-renal AKI 35.6% (n = 31/87) being the most frequent mechanisms (Table 2). Main etiologies of AKI were sepsis 57.5% (50/87), severe malaria 21.8% (19/87), hypovolemia 16.1% (14/87) and herbal concoctions 6.9% (6/87) (Table 3).

CKD accounted for 15.5% (n = 16) and Stage 5 was the most frequent (81.3%). (Table 2). Chronic glomerulonephritis (9/16) and urologic malformations (7/16) mainly posterior urethral valves were the causes of CKD (Table 4).

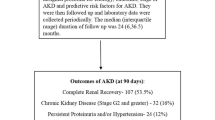

Eight of 14 (57.1%) patients with CKD, and 27 of 40 (67.5%) with AKI who required dialysis, accessed it. Reason for non-dialysis were lack of adapted equipment (57.9%), early death (26.3%), lack of finances (10.5%) and severe immunodepression (5.3%). Loss to follow up in CKD group was 37.5% (6/16) and 20.7% (18/87) in AKI. Of the 25 patients in the AKI group with available data at 3 months, renal recovery was complete in 22 (88%), partial in 1 (4%) and 2 (8%) were dialysis dependent. In- hospital mortality was 50.7% for AKI and 50% for CKD (Table 5). Factors associated to mortality were age < 96 months, (p = 0.001), the presence of a coma (p = 0.021), the use of herbal concoction (p = 0.024) and the presence of acute pulmonary oedema (p = 0.011). (Table 6).

Discussion

This study describe for the first time the epidemiology and outcomes of renal diseases in hospitalized children in the main tertiary referral hospital in Cameroon. The results show that children were mainly males, AKI accounted for the majority. Patients presented with severe disease. Chronic glomerulonephritis and urologic malformations were the causes of CKD while for AKI acute tubular necrosis and pre-renal AKI were the most frequent mechanism, with sepsis, severe malaria and herbal concoctions being the main etiologies. Almost half of the patients with need of dialysis did not access to the treatment mainly due to lack of adapted material, early death and financial constraint. Half of the patients died in the hospital, more than 1/4 of patients were lost to follow up. Renal recovery at 3 months in the AKI group was complete for the majority and two patients were dialysis dependent.

In this study, male patients were predominant. This is in accordance with other studies from developing countries and could be explained by the increased susceptibility of boys to renal disease and probably by some discrimination against women as it has been reported in SSA [18, 19, 21, 33, 34, 35]. Globally patients presented with severe renal insufficiency independently of the type. This presentation with severe disease has been reported in others studies in low-income countries in general and in SSA in particular [20, 21, 34, 36]. Possible reasons are: lack of early diagnosis, inadequate management of potential treatable risk factors, the silent evolution of kidney disease making that patients look for hospital only when the disease is manifested, and especially financial constraints that is a major concern in SSA where the majority of people are poor, and medical care is out of pocket payment [37].

The prevalence of CKD in this study was 15.5% amongst hospitalized children. This high figure was reported in studies in developing countries such as Iran (14.9%), in Jordan (17.3%) Nigeria (20.3%) [10, 38, 39]. In contrast, El Tigani et al. in Soudan [40] found a lower prevalence of 4%. Chronic glomerulonephritis and urologic malformations mostly posterior urethral valves were the mains etiologies of chronic renal failure in the present study. Ibasdin et al. in Nigeria [41] had similar findings. In most developing countries, chronic glomerulonephritis was the main etiology of CKD, with prevalence ranging from 30 to 60%. This could be due to the high prevalence of bacterial and parasitic infections that commonly affect the kidneys in developing countries [18, 19, 42, 43]. In contrast, urologic malformation was the main etiology in most western countries and the 3rd leading cause in Soudan [5, 40, 44]. Posterior urethral valve, a surgically treatable condition was the main urologic malformation responsible for chronic renal failure, raising the problem of late diagnosis, inadequate management of these children and inability to afford for the surgery. In this study, AKI was mainly due to sepsis, severe malaria and hypovolemia. This is in accordance with reported finding in SSA [20, 21, 34].

It is well known that access to renal replacement therapy (RRT) is very limited in SSA with a huge gap between those who required and received [45, 46]. In the present study an average of 62.2% of children who required dialysis, accessed it. This is in the range of the mean percent access to dialysis for children in SSA [21, 47]. Main reasons for non-dialysis in this study were lack of adapted dialysis material, early death due to late presentation, and financial restriction. Similarly Olowu et al. identified the same factors amongst children with renal failure in Nigeria (24).

Mortality rate and loss of follow up of children in the present study was high a situation already known in SSA [21, 32, 47, 48]. Almost half of the children died during hospitalization independently of the renal failure type. Compared to the pooled mortality rate of children in the world in general and in SSA in particular, our mortality for AKI was higher but in contrary lower for CKD [6, 21, 47]. This high mortality rate could be explained by many factors such as: the severity of the renal disease at presentation in the hospital, the impact of the underlying disease, the lack of adequate infrastructure, the financial constraints especially for those with end stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis. It is known that the cost of hemodialysis is unaffordable for most families in SSA [18, 24, 37, 49,50,51,52]. Attention should be paid to all these factors and the development of preventive nephrology in SSA is very important. This will reduce the morbidity and mortality of renal failure amongst children.

Our study has some limitations: the retrospective nature in which accuracy of data collection can be doubted. All the shortcoming of such a study design such as the absence standardization in the assessment of variables and the issue of missing data or cases. Also because of lack of diagnosis facilities (renal biopsies, genetic test), some disease may have underestimated in this study. Despite these limitations this study report for the first time the epidemiology and outcome of renal failure amongst children in Cameroon. This basic data give information that could help health planners in future to improve the outcome of children in our setting and to prevent the disease.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our data revealed that renal failure, especially AKI is common amongst children in Cameroon and they presented to the hospital with severe disease. Access to dialysis was limited by various factors and mortality rate was very high. This study also showed the challenges of the care of children with renal failure in a resource limited setting, where pediatrics nephrologists are almost inexistent. Implementation of health insurance, education of the population, and training of pediatric nephrologist are measure that could improve the outcome of these patients. More importantly is the prevention and treatment of primary disease.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acut Kidney Injury

- CKD:

-

Chronic Kidney Disease

- eGFR:

-

estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

- SSA:

-

Sub Saharan Africa

References

Cochat P, Mourani C, Exantus J, Bourquia A, Martinez-Pico M, Adonis-Koffy L, et al. Pediatric nephrology in developing countries. Medecine tropicale. 2009;69(6):543–7.

Alebiosu CO, Ayodele OE. The global burden of chronic kidney disease and the way forward. Ethnicity & disease. 2005;15(3):418–23.

Ardissino G, Dacco V, Testa S, Bonaudo R, Claris-Appiani A, Taioli E, et al. Epidemiology of chronic renal failure in children: data from the ItalKid project. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e382–7.

Meguid El Nahas A, Bello AK. Chronic kidney disease: the global challenge. Lancet. 2005;365(9456):331–40.

Van der Heijden BJ, van Dijk PC, Verrier-Jones K, Jager KJ, Briggs JD. Renal replacement therapy in children: data from 12 registries in Europe. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19(2):213–21.

Susantitaphong P, Cruz DN, Cerda J, Abulfaraj M, Alqahtani F, Koulouridis I, et al. World incidence of AKI: a meta-analysis. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2013;8(9):1482–93.

Etuk IS, Anah MU, Ochighs SO, Eyong M. Pattern of paediatric renal disease in inpatients in Calabar, Nigeria. Trop Dr. 2006;36(4):256.

Onifade EA. Ten-year review of childhood renal admissions into the Lagos University teaching hospital, Nigeria. Nigerian Quarterly Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2003;13(3–4):1–5.

Michael IO, Gabriel OE. Pattern of renal diseases in children in midwestern zone of Nigeria. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation. 2003;14(4):539.

Ocheke IE, Okolo SN, Bode-Thomas F, Agaba EI. Pattern of childhood renal diseases in Jos, Nigeria: a preliminary report. Journal of Medicine in the Tropics. 2010;12(2)

Bhatta N, Shrestha P, Budhathoki S, Kalakheti B, Poudel P, Sinha A, et al. Profile of renal diseases in Nepalese children. 2008.

Kari JA. Pediatric renal diseases in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. World journal of pediatrics : WJP. 2012;8(3):217–21.

Elzouki AY, Amin F, Jaiswal OP. Prevalence and pattern of renal disease in eastern Libya. Arch Dis Child. 1983;58(2):106–9.

Assounga AG, Assambo-Kieli C, Mafoua A, Moyen G, Nzingoula S. Etiology and outcome of acute renal failure in children in congo-brazzaville. Saudi journal of kidney diseases and transplantation. 2000;11(1):40–3.

Bailey D, Phan V, Litalien C, Ducruet T, Mérouani A, Lacroix J, et al. Risk factors of acute renal failure in critically ill children: a prospective descriptive epidemiological study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8(1):29–35.

Hui-Stickle S, Brewer ED, Goldstein SL, Pediatric ARF. Epidemiology at a tertiary care center from 1999 to 2001. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(1):96–101.

Van Biljon G. Causes, prognostic factors and treatment results of acute renal failure in children treated in a tertiary hospital in South Africa. J Trop Pediatr. 2008;54(4):233–7.

Anochie I, Eke F. Chronic renal failure in children: a report from Port Harcourt, Nigeria (1985-2000). Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18(7):692–5.

Rahman MH, Karim MA, Hoque E, Hossain MM. Chronic renal failure in children. Mymensingh medical journal : MMJ. 2005;14(2):156–9.

Esezobor CI, Ladapo TA, Osinaike B, Lesi FEA. Paediatric acute kidney injury in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria: prevalence, causes and mortality rate. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51229.

Olowu WA, Niang A, Osafo C, Ashuntantang G, Arogundade FA, Porter J, et al. Outcomes of acute kidney injury in children and adults in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(4):e242–e50.

Assounga AG, Assambo-Kieli C, Mafoua A, Moyen G, Nzingoula S. Etiology and outcome of acute renal failure in children in Congo-Brazzaville. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation. 2000;11(1):40.

Esezobor C, Oniyangi O, Eke F. Paediatric dialysis services in Nigeria: availability, distribution and challenges. West Afr J Med. 2011;31(3):181–5.

Olowu WA. Renal failure in Nigerian children: factors limiting access to dialysis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18(12):1249–54.

Halle MP, Ashuntantang G, Kaze FF, Takongue C, Kengne A-P. Fatal outcomes among patients on maintenance haemodialysis in sub-Saharan Africa: a 10-year audit from the Douala general Hospital in Cameroon. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17(1):165.

Halle MP, Takongue C, Kengne AP, Kaze FF, Ngu KB. Epidemiological profile of patients with end stage renal disease in a referral hospital in Cameroon. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16(1):59.

Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum J, Mehta R, Palevsky P. Acute renalfailure – definition, outcomemeasures, animal models, fluidtherapy and information technologyneeds: the second international consensus conference of the acute DialysisQuality initiative (ADQI) group. Crit Care. 2004;8(4):R204–12.

Akcan-Arikan A, Zappitelli M, Loftis L, Washburn K, Jefferson L, Goldstein SL, Modified RIFLE. Criteria in critically ill children with acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2007;71(10):1028–35.

Kramer H. The national kidney foundation's kidney disease outcomes quality initiative (KDOQI) grant initiative: moving clinical practice forward: WB Saunders; 2010.

Hogg R, Furth S, Lemley K, Portman R, Schwartz G, Coresh J, et al. National Kidney Foundation’s kidney disease outcomes quality initiative clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease in children and adolescents: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Pediatrics. 2003;111(6 Pt 1):1416–21.

Schwartz GJ, Brion LP, Spitzer A. The use of plasma creatinine concentration for estimating glomerular filtration rate in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Clin N Am. 1987;34(3):571–90.

Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A. International consensus conference on pediatric sepsis. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(1):2–8.

Cerdá J, Bagga A, Kher V, Chakravarthi RM. The contrasting characteristics of acute kidney injury in developed and developing countries. Nature clinical practice. Nephrology. 2008;4(3):138–53.

Ladapo TA, Esezobor CI, Lesi FE. Pediatric kidney diseases in an African country: prevalence, spectrum and outcome. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation. 2014;25(5):1110.

Ulasi I. Gender bias in access to healthcare in Nigeria: a study of end-stage renal disease. Trop Dr. 2008;38(1):50–2.

Halle MP, Kengne AP, Ashuntantang G. Referral of patients with kidney impairment for specialist care in a developing country of sub-Saharan Africa. Ren Fail. 2009;31(5):341–8.

Obiagwu PN, Abdu A. Peritoneal dialysis vs. haemodialysis in the management of paediatric acute kidney injury in Kano, Nigeria: a cost analysis. Tropical Med Int Health. 2015;20(1):2–7.

Derakhshan A, Al Hashemi GH, Fallahzadeh MH. Spectrum of in-patient renal diseases in children "a report from southern part Islamic Republic of Iran". Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation. 2004;15(1):12.

Radi MA. Childhood renal disorders in Jordan. J Nephrol. 1995;8:162–6.

Ali E-TM, Rahman AH, Karrar ZA. Pattern and outcome of renal diseases in hospitalized children in Khartoum state. Sudan Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics. 2012;12(2):52.

Michael IO, Gabriel OE. Pattern of renal diseases in children in midwestern zone of Nigeria. Saudi journal of kidney diseases and transplantation : an official publication of the Saudi Center for Organ Transplantation, Saudi Arabia. 2003;14(4):539–44.

Gulati S, Mittal S, Sharma RK, Gupta A. Etiology and outcome of chronic renal failure in Indian children. Pediatr Nephrol. 1999;13(7):594–6.

Harambat J, Van Stralen KJ, Kim JJ, Tizard EJ. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(3):363–73.

Ehlayel M, Akl K. Childhood chronic renal failure in Qatar. The British journal of clinical practice. 1991;46(1):19–20.

Anand S, Bitton A, Gaziano T. The gap between estimated incidence of end-stage renal disease and use of therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72860.

Liyanage T, Ninomiya T, Jha V, Neal B, Patrice HM, Okpechi I, et al. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet. 2015;385(9981):1975–82.

Ashuntantang G, Osafo C, Olowu WA, Arogundade F, Niang A, Porter J, et al. Outcomes in adults and children with end-stage kidney disease requiring dialysis in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(4):e408–e17.

Bah A, Kaba M, Diallo M, Kake A, Balde M, Keita K, et al. Renal diseases--morbidity and mortality in nephrology service, National Hospital Donka. Le Mali medical. 2005;21(4):42–6.

Arogundade F, Sanusi A, Okunola O, Soyinka F, Ojo O, Akinsola A. Acute renal failure (ARF) in developing countries: which factors actually influence survival. The Central African journal of medicine. 2006;53(5–8):34–9.

Balaka B, Douti K, Gnazingbe E, Bakonde B, Agbere A, Kessie K. Etiologies et pronostic de l’insuffisance rénale de l’enfant à l’hôpital universitaire de Lomé. Journal de la Recherche Scientifique de l'Universite de Lome. 2012;14(1).

Chijioke A, Makusidi A, Rafiu M. Factors influencing hemodialysis and outcome in severe acute renal failure from Ilorin, Nigeria. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation. 2012;23(2):391.

Ponsar F, Tayler-Smith K, Philips M, Gerard S, Van Herp M, Reid T, et al. No cash, no care: how user fees endanger health—lessons learnt regarding financial barriers to healthcare services in Burundi, Sierra Leone, Democratic Republic of Congo, Chad, Haiti and Mali. International Health. 2011;3(2):91–100.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author’s contributions

MPH: Conception and design of the study, and writing of the manuscript. CSL: Study conception, data collection and critical revision of the manuscript. EB: Study design, acquisition of data, data supervision and interpretation. HF: Supervision of data analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript. DH: Data analysis, and interpretation. BKM: Acquisition of Data, and supervision, Critical revision of the manuscript. CAA: Acquisition of data, supervision of data collection, Critical revision of the manuscript. EBP; Study conception and design and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We obtained ethical approval from the ethical board of the Douala University, and administrative authorization from the Douala General Hospital. In addition, patient data were de-identified before collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Halle, M.P., Lapsap, C.T., Barla, E. et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of children with renal failure in the pediatric ward of a tertiary hospital in Cameroon. BMC Pediatr 17, 202 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-017-0955-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-017-0955-0