Abstract

Background

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common mental disorders observed in childhood and adolescence. Its key symptoms — reduced attention, poor control of impulses as well as increased motor activity — are associated with decreased executive functions performance, finally affecting academic achievement. Although drug treatments usually show some effect, alternative treatments are continually being sought, due to lack of commitment and possible side effects. Cognitive trainings are frequently used with the objectives of increasing executive function performance. However, since transfer effects are limited and novelty and diversity are frequently ignored, interventions combining physical and cognitive demands targeting a broader range of cognitive processes are demanded.

Methods

The aim of the study is to examine the effects of a cognitively and physically demanding exergame on executive functions of children with ADHD. In a randomised clinical trial, 66 girls and boys diagnosed with ADHD (age 8–12) will be assigned either to an 8-week exergame intervention group (three training sessions per week à 30 min) or a waiting-list control group. Before and afterwards, the executive function performance (computer-based tests), the sport motor performance and ADHD symptoms will be assessed.

Discussion

The current study will offer insights into the effectiveness of a combination of cognitive and physical training using exergaming. Positive effects on the executive functions, sport motor performance and ADHD symptoms are hypothesized. Beneficial effects would mean a large degree of scalability (simple and cost-effective) and high utility for patients with ADHD.

Trial registration

KEK BE 393/15 (March 8, 2016); DRKS00010171 (March 14, 2016)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) display an increased risk of suffering from long-term academic, work-related and social impairments, which are linked to the key symptoms of ADHD: impaired attention, hyperactivity and lack of control of impulses [1]. ADHD is one of the most common disorders in childhood and adolescence with an estimated prevalence of 3–7% [2, 3], affecting more boys than girls [4]. The key symptoms usually already occur at pre-school age and may persist into adulthood [5]. Neurocognitive consequences of the disorder may take the form of deficient executive functions and motor deficiencies [6–8].

Although a large proportion of the symptoms can be reduced by medication, the main method of treatment [9], medications are also associated with a series of difficulties. Not all patients respond to treatment, about one third does not respond or responds poorly to treatment [10–12]. In some cases, side effects [13], low compliance [14] and as yet largely unknown long-term sequelae [15] occur. For these reasons, alternative methods of treatment are constantly being sought, which can improve the main functional deficits associated with the symptoms of ADHD. The prevailing explanation for the development of the key symptoms of ADHD is seen in a primary deficit in the executive functions [16].

Pronounced ADHD symptoms (attention deficit, hyperactivity, impulsiveness) are negatively correlated with the executive function performance [17–22]. Executive functions are viewed as meta-cognitions which are necessary for the top-down modulation of fundamental cognitive processes and therefore for carrying out goal-oriented activities [23]. Three fundamental processes can be seen as forming the core of the executive functions: inhibition, working memory and cognitive flexibility [24]. The executive functions are involved in all patterns of goal-oriented thought and behaviour and therefore control all behaviour that is relevant to learning [23], which explains the strong connection between learning success and executive functions in children in general [25] as well as in children with ADHD [26]. Promoting executive functions could therefore be a key pillar in a successful treatment strategy aiming to reduce the key symptoms of ADHD.

The positive influence of increased physical exercise on a wide range of areas of cognition has been repeatedly demonstrated for all age groups [27, 28]. In particular, inhibition and cognitive flexibility seem to profit from it [29]. Since children with ADHD often display deficient motor skills and motor control in addition to a functional deficit in their executive functions [30], increased physical exercise might be particularly important to this study population. Promising effects of physical activity, mostly based on acute studies, have been demonstrated in children with ADHD [31], and these might be explained by a potentially strong link between sensory motor skills, higher order cognitive processes and academic achievement [32]. Aside from these cross-sectional studies, experimental studies aiming to examine the longer-term influence of physical exercise on cognitive performance in childhood are rare [33] and even more so for children with ADHD [34].

The few existing intervention studies mostly reveal positive effects on cognitive performance [35–41], whereby multimodal treatment methods in particular are attributed with a greater efficacy and broader transfer effects (also to health and well-being). In this context, qualitative characteristics of the physical activity, such as adaptiveness to the individual performance level and cognitive demands, are attributed with playing a central role [42]. The fact that a training programme needs to be individually customised and adaptive in order to have positive effects on the executive functions is generally accepted in the field of cognitive training [43, 44].

The effectiveness of cognitive training programmes has increasingly been studied in children with ADHD in recent years [45]. This was mostly done using computerised, adaptive training programmes, aiming at attention processes, working memory or inhibition, for example. Neuropsychological deficits are to be reduced and transfer effects to the symptoms of ADHD and the general level of functioning are to be facilitated [46]. However, such effects seem to be limited to improvements in working memory performance [45]. Since most training programmes only aim at one area of the executive functions (e.g. working memory) [47], the transfer effects to other fundamental processes and to the ADHD symptoms as a whole continue to be a matter of controversy [48]. Thus, for example, improved working memory only leads to an improved learning performance if the child is able to block out (inhibit) irrelevant information. Cortese et al. [45] therefore call for innovative treatment programmes that increase transfer effects and that target multiple neuropsychological processes.

Just as there have been promising developments towards making cognitive training programmes as multifaceted as possible, the idea that highly varied, cognitively demanding sports activities offer an additional benefit for the executive functions [49] is increasingly being pursued in the field of physical training programmes too [23, 50]. A recent study [51] was able to demonstrate that a 6-week, cognitively demanding sports game intervention, but not a pure aerobic exercise intervention, had a positive influence on the cognitive flexibility of primary school children. In order to have the largest possible effect, Moreau and Conway [52] recommend a combined physical and cognitive training programme. This should ideally be carried out in the form of an ecologically valid but nevertheless controllable study.

An innovative combination of physical and cognitive training that takes into account the recommendations of Moreau and Conway [52] can be achieved with the help of “exergaming”. Exergaming is a portmanteau of “exercise” and “gaming” and refers to a new genre of interactive video games, which allow the gaming experience to be extended to the entire body [53]. In the light of existing motivational problems and a lower level of positive reinforcement, children with ADHD often find conventional training programmes boring and tiring [47]. “Gamification”, on the other hand, i.e. the use of game elements in non-game contexts [54, 55], appears to have a positive effect on motivation and training outcomes [56, 57]. This connection leads to a hybrid form that lies between a physical and cognitive training programme and a video game. This form of training ensures adaptivity. The duration, intensity, complexity and quality of execution of the physical training can be measured. No studies currently exist on exergames and their effects on the cognitive skills of children with ADHD. However, initial investigations with children and adolescents have yielded promising results and therefore seem to demonstrate the usefulness of exergames as an intervention for promoting health-related outcomes [58] and the executive functions [59–62].

Study aims and hypotheses

The aim of this study is to evaluate the influence of an exergame intervention, which is characterised by both high physical and high cognitive demands, on the executive functions of children with ADHD. We expect that exergaming will have a positive impact on the executive functions, the sport motor performance, the symptoms of ADHD and on quality of life.

As the primary outcome, we hypothesize that exergaming will positively affect executive function performance compared to controls. More specifically, we expect that the demanding exergame activity that will be carried out over a period of 8 weeks will have a beneficial effect on the key areas—inhibition, working memory and cognitive flexibility—and that we will be able to detect a significant effect (significance level α = .05) with small to moderate effect sizes.

As secondary outcomes, we hypothesize that sport motor performance will be significantly improved by the planned intervention (physically strenuous exergaming). As a further secondary outcome, the influence of the intervention on the symptoms of ADHD will be examined. Based on studies into physical training programmes for children and adolescents with ADHD [42], we hypothesize the intervention to have a positive effect. In addition, quality of life is to be measured as a further secondary outcome serving as an indication of a broad transfer. We expect exergaming to have a positive influence on quality of life. The expectations of registering positive developments with respect to the secondary outcomes are generally somewhat more conservative. Based on the available empirical evidence, we therefore expect to obtain small effect sizes.

Methods/Design

Study design

The present study will be carried out using a randomised study design with a waiting-list control group in Bern, Switzerland. Each participant in the study will take part in the study for a total of nine weeks, being assigned either to the exergame intervention or to the passive waiting-list control group.

Participants

In total, 66 children with ADHD between the ages of 8 and 12 years should be examined. Any child that has been diagnosed with the ADHD is eligible to take part in the study. Beyond this, the participants and legal guardians must examine the information relating to the study and give their informed consent to take part in the study. As the well-being of the participants is the main priority, people whose mental or physical integrity might be threatened by the study must not take part in it. For safety reasons, people suffering from a neurological disorder, Tourette syndrome or an epileptic disorder will not be allowed to take part. To recruit the study participants, we will collaborate with elpos Schweiz (an association for parents and caregivers of children and adults with ADHD). The sample size of 66 participants was calculated using G*Power [63] for a general linear model with repeated measures (two comparison groups; three measurements; “within-between interaction”; correlation between measurements = .8), with a power of .80 [64] and a small effect size.

Intervention

The planned exergame intervention for the experimental group will be carried out using the XBOX Kinect. This device is able to project the player and his or her movements on the screen by means of a camera. It therefore offers the possibility of immersing oneself directly in all sorts of different virtual worlds. The level of physical activity can be increased playfully, and a continuous adjustment to the corresponding level of performance allows the executive functions to be trained. A physically demanding exergame with a strong cognitive component is “Shape UP” (Ubisoft, Montreal, Canada). It is available as a commercial game and resorts to various different elements of endurance, strength and mobility, as well as coordination, working memory, inhibition, attention, speed of action and action planning. In an initial pilot study involving school children, acute effects on cognitive flexibility were noted [62]. In order to achieve the highest possible performance, the player must train both physically and cognitively. The game is designed to be adaptive, automatically adjusting to the player’s level of proficiency. Within the game, there are several different “workouts”, which subjects are supposed to carry out three times a week for at least 30 min, over a period of 8 weeks. The first exergaming session will be conducted under the supervision of the researcher, and at the same time, the intervention will be explained to the children. The parents will be asked to assist and support the children in carrying it out. They too will be given an introduction and brief instructions as to how the game is played. The children and their parents will be informed that they are welcome to contact the study coordinator at any time if they need information or assistance.

Outcome measures and time-points of assessment

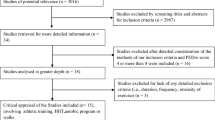

The study is divided up into five phases (T1-T5). These are discussed in chronological order below (see Fig. 1):

-

Baseline (T1): At the beginning of the study, the participants will be fitted with an accelerometer (Actigraph GT9X), which they are expected to wear during the entire study, to monitor their physical activity level. By measuring the acceleration in three-dimensional space, it is for example possible to calculate step counts and MET levels. Participants will be asked to wear the devices at night too, if possible, to obtain data on sleep duration.

-

Pre-intervention measurement (T2): The executive functions, sport motor performance, ADHD symptoms, quality of life and background variables will be measured 7 days after handing over the accelerometer. The measures used to determine the executive functions: working memory, cognitive flexibility and inhibition, are based on three standardised tests. They are specifically designed for the age group in question and have proven their age adequacy and sensitivity to changes in executive function performance in previous studies [e.g. 51, 65]: working memory performance will be measured using the colour span backwards [66], in which the number of correct answers will be rated. Cognitive flexibility and inhibition will be measured using the adapted Flanker Test [65, 67, 68], again by computer-assisted means. In this, the scores for accuracy and reaction time will be determined. In addition, an adapted version of the Simon Task [69] will be used. The tests have already been successfully used in several studies [51, 65, 70] and proved to be sensitive enough to detect both acute and chronic effects in children between the ages of 8 and 12 years. The cognitive test battery will last approx. 20 min overall. Sport motor performance will be measured using the German Motor Test Battery 6–18, which includes eight test items measuring endurance and coordination [71]. Beyond this, the German version of the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale will be used to measure the subjective pleasure in physical activity [72]. The Shuttle-run Test [73] will be used to measure physical fitness. The ADHD symptoms will be ascertained using the German version [74] of the Conners-3 Scales on Attention and Behaviour [75]. These will be completed by parents and teachers. Quality of life will be measured using the Inventory of Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents [76]. This questionnaire will be completed by parents and teachers. The background variables will be determined using questionnaires and will include the following: age, sex, height, weight, socioeconomic status [77], exercise behaviour [78], and pubertal development [79], completed by the parents.

-

Intervention phase (T3): The children in the experimental group will train three times a week for approx. 30 min over a period of 8 weeks. The frequency of training and the accuracy will be recorded by the XBOX Kinect and using a Training Diary. In addition, the exercise activity will be recorded by an accelerometer (over a period of 8 weeks) and the heart rate will be recorded by a cardio belt (only during intervention sessions).

-

Post-intervention measurement (T4) and follow-up (T5): At these two times (immediately after the conclusion of the study, and again four weeks later) the tests and questionnaires on the executive functions, quality of life, sport motor performance, attention and behaviour used at T2 will be performed once again.

Randomisation and blinding

Participants will be randomly assigned to either the intervention or the control group. The randomisation will be conducted in accordance with the regulations of the ethics committee. The teachers will be blinded with respect to treatment allocation, to ensure the data is objective. It will not be possible to blind the researchers and parents since they have to provide guidance on the intervention. Assessments will be performed by two examiners, but as most of the assessments used are objective, the risk of the researcher imposing a bias is small.

Adverse events

No serious adverse events are expected as a consequence of the treatment. Slight muscle and joint ache might occur and subjects’ eyes may tire. Health and safety precautions that apply to the XBOX Kinect and the exergame must be strictly observed.

Data analysis

The data collected (background variables, primary and secondary outcomes) will be tested as to their statistical properties and analysed accordingly. Normally distributed background and control variables will be compared between the groups (experimental vs. control group) using the two-sample t-test, and non-normally-distributed variables will be tested using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. A chi-squared test will be used for the categorical variables. Significant differences might be considered as covariates for further analyses.

The diary entries as well as the execution data obtained from the XBOX and the heart rate during training sessions will be used to provide information about the focus and the frequency of the training as well as about the level of physical exertion during exergaming. These scores will be presented as descriptive summaries. The frequency of exercises (including step count, MET level) during the intervention period will then be compared between the groups and analysed using an independent t-test.

In order to test the hypotheses, the primary and secondary outcome variables will be analysed using repeated measures ANOVAs, if applicable. To determine whether a repeated measures ANOVA is applicable, the pre-intervention scores will be tested using an independent t-test to determine any differences between groups. Provided no significant differences are found, the repeated measures ANOVAs can be performed. If, on the other hand, significant differences are found, an ANCOVA should be carried out on the baseline data to check the differences. In this case, the pre-intervention scores will serve as covariates, and the post-intervention scores will be introduced as dependent variables.

The significance level will be set at p < .05 for all analyses. The results will be reported in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines for clinical trials [80].

Research ethics

The submitted research project has been approved by the ethics committee of the canton of Bern, Switzerland (KEK-NR. 393/15). In addition, the research project has been registered with the Swiss National Clinical Trial Port and the German Register of Clinical Trials (DRKS00010171). After verifying that they are eligible for the study, the participants and their parents will receive adequate verbal information about the study. They will be given enough time to consider their participation and the informed consent information will be sent to them. After at least another seven days, the researcher will visit the families and they will go through the written consent form together. Children above the age of 11 years will be appropriately informed in writing in addition to the oral information. Participation in the study can be terminated at any time without stating the reasons and without detriment to the participant.

Discussion

The existing empirical evidence indicates that physical activity can have a positive effect on cognitive performance, physical activity and the symptoms of ADHD [31, 42]. In addition, exergame interventions have shown that they are able to increase physical activity and motivation [53]. Particularly in children with ADHD, no scientific findings are currently available from studies that have examined the effects of exergaming.

Various different studies have been able to demonstrate that both physical and cognitive training programmes can have a positive effect on the executive functions [e.g. 27, 28, 44, 45]. Because novelty and diversity are frequently ignored in cognitive trainings, beneficial effects are limited. Therefore, a hybrid between a physical and cognitive training, presented in a child-appropriate form might be a promising approach to foster executive function performance [52]. This is particularly interesting in the light of the fact that children and adolescents with ADHD spend about twice as much time playing video games [81], which could be due to the fact that they prefer the immediate rewards associated with video game play to the delayed rewards associated, for example, with traditional physical activity [82]. A direct form of reward occurs during and immediately after exergaming via the feedback from the computer and the number of points scored. If the effects are found to be positive, it would be desirable to replace some of the time already spent playing video games by exergaming. Thus, the current research project has direct potential applications: if exergaming is able to promote positive effects, it will become useable as an instrument that is already widely available.

From the point of view of society as a whole, fewer and fewer people are engaging in sports and more and more are failing to meet the recommended daily time spent in physical activity [83]. Physical activity is decreasing and many activities are done seated [84]. At the same time, the amount of time spent in front of screens is becoming longer and longer [81], leading to a link between media use, body fatness and physical activity in children and adolescents [85] and reflecting the particular vulnerability of this study population. In addition, particularly children with ADHD have problems taking part in traditional sports programmes and not dropping out of these [86], which can have negative consequences in many areas, because physical inactivity in children and adults has many effects that are detrimental to health and can be seen as a major health factor [87]. New methods are therefore needed to place the focus on health promotion through sports, and in particularly to encourage children and adolescents who are overtaxed by traditional programmes.

A few limitations need to be mentioned, which might affect the results of the study. First of all, a waiting-list control group is planned, ensuring an economic procedure in view of the low level of available empirical evidence. Should the results be favourable, an exergame intervention would have to be compared with a cognitive training and with a regular physical training programme. The planned exergame intervention is a physical training programme with a high cognitive component. The product in question is commercially available so that the entertainment factor is large and the graphics are appealing. Unfortunately, the exergame was not produced and adapted for the specific use in the current study. As a consequence, the cognitive engagement is greater in some of the game’s levels and lower in others. The cognitive engagement of a cognitive training and an optimal challenge point might not be reached all the time.

One of the strengths of the study is its high ecological validity. Children and adolescents with ADHD often play video games. It would therefore seem to be easy to implement active video games at home, and this is being investigated by an increasing number of studies [88]. Furthermore, the study will be randomised and use a large number of control variables, which will allow the sports activity as well as the physical activity of the children to be observed. We therefore expect to also obtain valuable insights beyond the intervention itself.

Trial status

Recruitment for the trial started in March 2016 and is estimated to be completed by June 2017.

Abbreviations

- ADHD:

-

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- ANCOVA:

-

Analysis of covariance

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated standards of reporting trials

- MET:

-

Metabolic equivalent of task

References

Johnston C, Park JL. Interventions for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a year in review. Curr Dev Disord Rep. 2015;2:38–45.

Polanczyk GV, Willcutt EG, Salum GA, Kieling C, Rohde LA. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:434–42.

Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:942–8.

Gershon J, Gershon J. A meta-analytic review of gender differences in ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2002;5:143–54.

Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:565–76.

Boonstraa M, Oosterlaan J, Sergeant JA, Buitelaar JK. Executive functioning in adult ADHD: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1097–135.

Martin NC, Piek J, Baynam G, Levy F, Hay D. An examination of the relationship between movement problems and four common developmental disorders. Hum Mov Sci. 2010;29:799–808.

Piek JP, Pitcher TM, Hay DA. Motor coordination and kinaesthesis in boys with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41:159–65.

Coghill DR, Seth S, Pedroso S, Usala T, Currie J, Gagliano A. Effects of methylphenidate on cognitive functions in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: evidence from a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76:603–15.

Connor DF. Stimulants. In: Barkley RA, editor. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a handbook for diagnosis and treatment. New York: Guilford; 2006. p. 608–47.

Wigal SB, Emmerson N, Gehricke JG, Galassetti P. Exercise: applications to childhood ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2013;17:279–90.

Faraone SV, Biederman J, Spencer TJ, Aleardi M. Comparing the efficacy of medications for ADHD using meta-analysis. Medscape Gen Med. 2006;8:4.

Graham J, Banaschewski T, Buitelaar J, Coghill D, Danckaerts M, Dittmann RW, Döpfner M, Hamilton R, Hollis C, Holtmann M, Hulpke-Wette M, Lecendreux M, Rosenthal E, Rothenberger A, Santosh P, Sergeant J, Simonoff E, Sonuga-Barke E, Wong ICK, Zuddas A, Steinhausen H-C, Taylor E, European Guidelines Group. European guidelines on managing adverse effects of medication for ADHD. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:17–37.

Adler LD, Nierenberg AA. Review of medication adherence in children and adults with ADHD. Postgrad Med. 2010;122:184–91.

MTA Cooperative Group. National institute of mental health multimodal treatment study of ADHD follow-up: 24-month outcomes of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2004;113:754–61.

Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, Faraone SV, Pennington BF. Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1336–46.

Burgess GC, Depue BE, Ruzic L, Willcutt EG, Du YP, Banich MT. Attentional control activation relates to working memory in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:632–40.

Crosbie J, Arnold P, Paterson A, Swanson J, Dupuis A, Li X, Shan J, Goodale T, Tam C, Strug LJ, Schachar RJ. Response inhibition and ADHD traits: correlates and heritability in a community sample. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41:497–507.

Kofler MJ, Rapport MD, Bolden J, Sarver DE, Raiker JS. ADHD and working memory: the impact of central executive deficits and exceeding storage/rehearsal capacity on observed inattentive behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38:149–61.

Raiker JS, Rapport MD, Kofler MJ, Sarver DE. Objectively-measured impulsivity and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): testing competing predictions from the working memory and behavioral inhibition models of ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40:699–713.

Rapport MD, Bolden J, Kofler MJ, Sarver DE, Raiker JS, Alderson RM. Hyperactivity in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a ubiquitous core symptom or manifestation of working memory deficits? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2009;37:521–34.

Tillman C, Eninger L, Forssman L, Bohlin G. The relation between working memory components and ADHD symptoms from a developmental perspective. Dev Neuropsychol. 2011;36:181–98.

Diamond A. Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64:135–68.

Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cogn Psychol. 2000;41:49–100.

Mulder H, Cragg L. Executive functions and academic achievement: current research and future directions. Infant Child Dev. 2014;23:1–3.

Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Doyle AE, Seidman LJ, Wilens TE, Ferrero F, Morgan CL, Faraone SV. Impact of executive function deficits and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on academic outcomes in children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:757–66.

Chang YK, Labban JD, Gapin JI, Etnier JL. The effects of acute exercise on cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Brain Res. 2012;1453:87–101.

Verburgh L, Konigs M, Scherder EJA, Oosterlaan J. Physical exercise and executive functions in preadolescent children, adolescents and young adults: a meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:973–9.

Barenberg J, Berse T, Dutke S. Executive functions in learning processes: do they benefit from physical activity? Educ Res Rev. 2011;6:208–22.

Kaiser ML, Schoemaker MM, Albaret JM, Geuze RH. What is the evidence of impaired motor skills and motor control among children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? systematic review of the literature. Res Dev Disabil. 2015;36:338–57.

Vysniauske R, Verburgh L, Oosterlaan J, Molendijk ML. The effects of physical exercise on functional outcomes in the treatment of ADHD: a meta-analysis. J Atten Disord. 2016; doi:10.1177/1087054715627489.

Davis AS, Pass LA, Finch WH, Dean RS, Woodcock RW. The canonical relationship between sensory-motor functioning and cognitive processing in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;24:273–86.

Diamond A, Lee K. Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science. 2011;333:959–64.

Lehnert K. Der Einfluss von Sport auf kognitive Funktionen bei Kindern mit ADHS [The influence of exercise on cognitive functions in children with ADHD]. Z Sportpsychol. 2014;21:104–18.

Chang YK, Hung CL, Huang CJ, Hatfield BD, Hung TM. Effects of an aquatic exercise program on inhibitory control in children with ADHD: a preliminary study. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2014;29:217–23.

Coi JW, Han DH, Kang KD, Jung HY, Renshaw PF. Aerobic exercise and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2015;47:33–9.

Kang K, Choi J, Kang S, Han D. Sports therapy for attention, cognitions and sociality. Int J Sports Med. 2011;32:953–9.

Park MS, Byun KW, Park YK, Kim MH, Jung SH, Kim H. Effect of complex treatment using visual and auditory stimuli on the symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. J Exerc Rehabil. 2013;9:316–25.

Smith AL, Hoza B, Linnea K, McQuade JD, Tomb M, Vaughn AJ, Shoulberg EK, Hook H. Pilot physical activity intervention reduces severity of ADHD symptoms in young children. J Atten Disord. 2013;17:70–82.

Verret C, Guay MC, Berthiaume C, Gardiner P, Beliveau L. A physical activity program improves behavior and cognitive functions in children with ADHD: an exploratory study. J Atten Disord. 2012;16:71–80.

Ziereis S, Jansen P. Effects of physical activity on executive function and motor performance in children with ADHD. Res Dev Disabil. 2015;38:181–91.

Neudecker C, Mewes N, Reimers AK, Woll A. Exercise interventions in children and adolescents with ADHD: a systematic review. J Atten Disord. 2015. doi:10.1177/1087054715584053.

Klingberg T. Training and plasticity of working memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14:317–24.

Klingberg T, Forssberg H, Westerberg H. Training of working memory in children with ADHD. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2002;24:781–91.

Cortese S, Ferrin M, Brandeis D, Buitelaar J, Daley D, Dittmann RW, Holtmann M, Santosh P, Stevenson J, Stringaris A, Zuddas A, Sonuga-Barke EJS. Cognitive training for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis of clinical and neuropsychological outcomes from randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54:164–74.

Klingberg T, Fernell E, Olesen PJ, Johnson M, Gustafsson P, Dahlström K, Gillberg CG, Forssberg H, Westerberg H. Computerized training of working memory in children with ADHD–a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:177–86.

Dovis S, Van der Oord S, Wiers RW, Prins PJM. Improving executive functioning in children with ADHD: training multiple executive functions within the context of a computer game. a randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121651.

Rapport MD, Orban SA, Kofler MJ, Friedman LM. Do programs designed to train working memory, other executive functions, and attention benefit children with ADHD? a meta-analytic review of cognitive, academic, and behavioral outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:1237–52.

Schmidt M, Benzing V, Kamer M. Classroom-based physical activity breaks and children’s attention: cognitive engagement works! Front Psychol. 2016;7:1–13.

Diamond A, Ling DS. Conclusions about interventions, programs, and approaches for improving executive functions that appear justified and those that, despite much hype, do not. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2016;18:34–48.

Schmidt M, Jäger K, Egger F, Roebers CM, Conzelmann A. Cognitively engaging chronic physical activity, but not aerobic exercise, affects executive functions in primary school children: a group-randomized controlled trial. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2015;37:575–91.

Moreau D, Conway ARA. The case for an ecological approach to cognitive training. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18:334–6.

Best JR. Exergaming in youth. Z Psychol. 2013;221:72–8.

Deterding S, Sicart M, Nacke L, O’Hara K, Dixon D. Gamification. Using game-design elements in non-gaming contexts. In: CHI’11 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York: ACM; 2011. p. 2425–2428.

Deterding S, Dixon D, Khaled R, Nacke L. From game design elements to gamefulness: defining gamification. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments. New York: ACM; 2011. p. 9–15.

Dovis S, Van der Oord S, Wiers RW, Prins PJM. Can motivation normalize working memory and task persistence in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? the effects of money and computer-gaming. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40:669–81.

Prins PJM, Dovis S, Ponsioen A, ten Brink E, van der Oord S. Does computerized working memory training with game elements enhance motivation and training efficacy in children with ADHD? Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14:115–22.

Primack BA, Carroll MV, McNamara M, Klem ML, King B, Rich M, Chan CW, Nayak S. Role of video games in improving health-related outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:630–8.

Best JR. Exergaming immediately enhances children’s executive function. Dev Psychol. 2012;48:1501–10.

Flynn RM, Richert RA, Staiano AE, Wartella E, Calvert SL. Effects of exergame play on ef in children and adolescents at a summer camp for low income youth. J Educ Dev Psychol. 2014;4:209–25.

Staiano AE, Abraham AA, Calvert SL. Competitive versus cooperative exergame play for African american adolescents’ executive function skills: short-term effects in a long-term training intervention. Dev Psychol. 2012;48:337–42.

Benzing V, Heinks T, Eggenberger N, Schmidt M. Acute cognitively engaging exergame-based physical activity enhances executive functions in adolescents. PLoS ONE. in press. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0167501.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciencies. Abingdon: Routledge; 1988.

Jäger K, Schmidt M, Conzelmann A, Roebers CM. Cognitive and physiological effects of an acute physical activity intervention in elementary school children. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1473.

Schmid C, Zoelch C, Roebers CM. Das Arbeitsgedächtnis von 4- bis 5-jährigen Kindern: Theoretische und empirische Analyse seiner Funktionen [Working memory in 4- to 5-year-old children: theoretical issues and empirical findings]. Z Entwickl Padagogis. 2008;40:2–12.

Eriksen BA, Eriksen CW. Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Percept Psychophys. 1974;16:143–9.

Röthlisberger M, Neuenschwander R, Cimeli P, Michel E, Roebers CM. Improving executive functions in 5- and 6-year-olds: evaluation of a small group intervention in prekindergarten and kindergarten children. Infant Child Dev. 2012;21:411–29.

Kauer M, Roebers CM. Kognitive Basisfunktionen und motorisch-koordinative Kompetenzen in Abhängigkeit des Peerstatus bei Kindern zu Beginn der Schulzeit [Cognitive and motor coordinative abilities in children of different peer status groups in the first school year]. Z Entwickl Padagogis. 2012;44:139–52.

Jäger K, Schmidt M, Conzelmann A, Roebers CM. The effects of qualitatively different acute physical activity interventions in real-world settings on executive functions in preadolescent children. Ment Health Phys Act. 2015;9:1–9.

Bös K, Schlenker L, Büsch D, Lämmle L, Müller H, Oberger J, Seidel, I, Tittelbach S. Deutscher Motorik-Test 6–18 (DMT 6–18) [German motor performance test (DMT 6–18)]. Hamburg: Czwalina; 2009.

Jekauc D, Voelkle M, Wagner MO, Mewes N, Woll A. Reliability, validity, and measurement invariance of the German version of the physical activity enjoyment scale. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38:104–15.

Léger LA, Mercier D, Gadoury C, Lambert J. The multistage 20 m shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. J Sports Sci. 1988;6:93–101.

Lidzba K, Christiansen H, Drechsler R. Conners Skalen zu Aufmerksamkeit und Verhalten – 3 [Conners rating scales of attention and behavior]. Bern: Huber; 2013.

Conners CK. Conners’ rating scales revised. Technical manual. North Tonawanda: Multi-Health Systems, Incorporated; 2001.

Mattejat F, Remschmidt H. Das Inventar zur Erfassung der Lebensqualität bei Kindern und Jugendlichen (ILK) [The inventory of life quality in children and adolescents ILC]. Bern: Huber; 2006.

Boudreau B, Poulin C. An examination of the validity of the family affluence scale II (FAS II) in a general adolescent population of Canada. Soc Indic Res. 2008;94:29–42.

Fuchs R, Klaperski S, Gerber M, Seelig H. Messung der Bewegungs- und Sportaktivität mit dem BSA-Fragebogen [Measurement of physical activity and sport activity with the BSA questionnaire]. Z Gesundh. 2015;23:60–76.

Watzlawik M. Die Erfassung des Pubertätsstatus anhand der Pubertal Development Scale: Erste Schirtte zur Evaluation einer deutschen Übersetzung [Assessing pubertal status with the Pubertal Development Scale: first steps towards an evaluation of a German translation]. Diagnostica. 2009;55:55–65.

Schulz, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010;8:18.

Weiss MD, Baer S, Allan BA, Saran K, Schibuk H. The screens culture: impact on ADHD. Atten Deficit Hyperact Disord. 2011;3:327–34.

O’Neill SC, Berwid OG, Bédard ACV. The exercise–cognition interaction and ADHD. In: Exercise-Cognition Interaction. San Diego: Academic; 2016. p. 375–98.

Carson V, Staiano AE, Katzmarzyk PT. Physical activity, screen time, and sitting among us adolescents. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2015;27:151–9.

Henson J, Yates T, Biddle SJH, Edwardson CL, Khunti K, Wilmot EG, Gray LJ, Gorely T, Nimmo MA, Davies MJ. Associations of objectively measured sedentary behaviour and physical activity with markers of cardiometabolic health. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1012–20.

Marshall SJ, Biddle SJH, Gorely T, Cameron N, Murdey I. Relationships between media use, body fatness and physical activity in children and youth: a meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2004;28:1238–46.

Lee H, Causgrove Dunn J, Holt NL. Youth sport experiences of individuals with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Adapt Phys Act Q. 2014;31:343–61.

Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380:219–29.

Kauhanen L, Jarvela L, Lahteenmaki PM, Arola M, Heinonen OJ, Axelin A, Lilius J, Vahlberg T, Salantera S. Active video games to promote physical activity in children with cancer: a randomized clinical trial with follow-up. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:94.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the “Stiftung Suzanne und Hans Biäsch zur Förderung der Angewandten Psychologie” and the “Hans & Annelies Swierstra Stiftung” for their funding. In advance, we would like to thank the participating parents and children. Thanks to Gina Galli for her dedicated work and for getting in touch with elpos. We gratefully thank Gina Galli, Denise Wenk, Jacqueline Hangl, Remo Burri, Erika Marti and Nicola Biesold for performing the assessments. Special thanks to the assistance of Gina Galli and Denise Wenk for preparing the assessments and contacting parents and teachers.

Funding

This study is supported by the foundations “Stiftung Suzanne und Hans Biäsch zur Förderung der Angewandten Psychologie” and “Hans & Annelies Swierstra Stiftung”.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

Both Authors contributed equally to the set-up of the experimental study design and the ethics approval. The original manuscript was drafted, reviewed and commented by VB and MS. Assessments and study coordination will be conducted by VB and MS. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The submitted research project has been approved by the ethics committee of the canton of Bern, Switzerland (KEK-NR. 393/15; March 8, 2016). In addition, the research project has been registered with the Swiss National Clinical Trial Port and the German Register of Clinical Trials (DRKS00010171; March 14, 2016). After verifying that they are eligible for the study, the participants and their parents will receive adequate verbal information about the study. They will be given enough time to consider their participation and the informed consent information will be sent to them. After at least another seven days, the researcher will visit the families and they will go through the written consent form together. Children above the age of 11 years will be appropriately informed in writing in addition to the oral information. Participation in the study can be terminated at any time without stating the reasons and without detriment to the participant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Benzing, V., Schmidt, M. Cognitively and physically demanding exergaming to improve executive functions of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomised clinical trial. BMC Pediatr 17, 8 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0757-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0757-9