Abstract

Background

Attrition is a serious problem in intervention studies. The current study analyzed the attrition rate during follow-up in a randomized controlled pediatric weight management program (EPOC study) within a tertiary care setting.

Methods

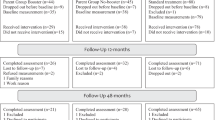

Five hundred twenty-three parents and their 7–13-year-old children with obesity participated in the randomized controlled intervention trial. Follow-up data were assessed 6 and 12 months after the end of treatment. Attrition was defined as providing no objective weight data. Demographic and psychological baseline characteristics were used to predict attrition at 6- and 12-month follow-up using multivariate logistic regression analyses.

Results

Objective weight data were available for 49.6 (67.0) % of the children 6 (12) months after the end of treatment. Completers and non-completers at the 6- and 12-month follow-up differed in the amount of weight loss during their inpatient stay, their initial BMI-SDS, educational level of the parents, and child’s quality of life and well-being. Additionally, completers supported their child more than non-completers, and at the 12-month follow-up, families with a more structured eating environment were less likely to drop out. On a multivariate level, only educational background and structure of the eating environment remained significant.

Conclusions

The minor differences between the completers and the non-completers suggest that our retention strategies were successful. Further research should focus on prevention of attrition in families with a lower educational background.

Trial registration

Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN24655766. Registered 06 September 2008, updated 16 May 2012.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Attrition is a serious problem in intervention studies, which can threaten reliability and validity for several reasons: First, when participants drop out of a study, analyses are limited to a smaller sample, which can lead to insufficient statistical power. Second, although participants may drop out for various reasons, some of these can be related to the outcome. Third, the drop-out pattern may differ between treatment groups, altering the random composition of the groups and leading to confounding influences. Therefore, high attrition rates can cause a significant bias in the study. Such a bias might alter the characteristics of a sample and impede the comparability to the original sample. Moreover, the bias might alter the covariance of the variables included, possibly affecting outcomes or other correlated variables (as reviewed by Ahern [1]).

Reviewing the attrition rates in randomized controlled studies of chronic illness in childhood, Karlson and Rapoff [2] reported that on average, 37 % (range 0–75 %) refused to take part in the study at the beginning, 4 % (range 0–35 %) provided no baseline data, 20 % (range 0–54 %) no initial follow-up data, and 32 % (range 0–59 %) no long-term follow-up data. The majority of the studies did not analyze differences between completers and non-completers. Collins et al. [3] assessed the efficacy of dietetic interventions for children with obesity. From the 37 randomized controlled trials (RCT) they extracted, 26 included follow-up data (1 month to 10 years). Attrition rates during follow-up varied from 5 to 37 %. Only 9 studies reported efficacy data on the basis of an intention-to-treat analysis.

In general, only a small number of studies have reported explicit loss at follow-up. In a recent family-focused intervention study [4], approximately 20 % of participants dropped out at the follow-up assessments. These children were significantly older and had a higher body mass index (BMI) z-score at baseline. This is in line with the findings of van den Aker et al. [5], who reported an attrition rate of 33 % at the 1-year follow-up, with drop-outs being older and less successful during treatment. McCallum et al. [6] stated that the children lost in follow-up were slightly heavier, and that their parents reported a lower quality of life for their children. Unfortunately, it was not reported whether these differences were statistically significant. Hughes et al. [7] observed a 34.9–36.9 % loss during follow-up 12 months after the start of treatment, and did not report any demographic differences between completers and non-completers. This is in line with the data of Savoye et al. [8], who found no differences between completers and non-completers with respect to baseline characteristics (BMI, age, gender).

Other studies examined the determining factors for drop-out during treatment [9], with fairly inconclusive results, as almost no overlap was found between the indicators analyzed. Although some studies reported a higher attrition rate for those with a higher BMI z-score [10–13], others did not find a significant effect (n.s. [14, 15]), older age [10, 11, 13] (n.s. [14–16]), ethnic minority status [10, 14, 15] (n.s. [11, 16]), lower socioeconomic status (SES)/education (trend [17]; n.s. [12, 16]) or psychological problems [10, 13, 17] (n.s. [11, 12]). Consistently, no study reported gender effects [11–13, 15–17].

To be able to adequately interpret study results, it is crucial to achieve high retention rates in intervention research. Participants’ motivation to devote time and effort to filling in questionnaires or attending medical check-ups will decrease over time, and this may be particularly true when treatment takes place in inpatient facilities that are far from patients’ homes. Hence, knowledge regarding predictors of attrition during follow-up in clinical trials is limited. Therefore, we analyzed the data of a large randomized controlled study (Empowering Parents of Obese Children – EPOC study) in order to examine which factors predicted failure to provide objective weight-related measurements. We hypothesized that parents with a lower educational background and children experiencing less success during treatment and higher psycho-social strain would return objective weight data less frequently.

Methods

Sample and procedure

Written consent was obtained from parents of 7–13-year-old children with obesity to take part in the EPOC study examining the effects of supplementary parent training as part of the child’s inpatient obesity intervention. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in detail elsewhere [18]. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Potsdam on 19 May 2006.

Children’s weight and height were measured by a physician, who was blind to the treatment group to which they were assigned, at different time periods: at baseline (beginning of the intervention), post-intervention and six and twelve months thereafter. In addition, parents and their children filled in a set of questionnaires. Table 1 provides a sample description of the study’s 523 children (274, 52.4 % girls) and their parents at baseline.

Measurements

Demographic and weight data

Parents were asked to provide demographic information such as age, family status and educational level (number of years spent in school) at the beginning of their child’s inpatient stay. In addition, all parents reported their own height and weight, as well as the respective data of their partners. Children were weighed in light underwear by a physician on a standard beam scale (accurate to 100 g) and measured using a calibrated stadiometer (accurate to 1 cm). Thereafter, a standardized BMI (BMI-SDS) for age and sex was calculated [19]. Several steps were taken to minimize loss to follow-up. To obtain objective weight data, we conducted a 6- and 12-month follow-up by contacting families and physicians by post. If families did not provide the weight data within 3 weeks, a reminder was sent by post. For the 12-month follow-up, we also telephoned the families that had still not replied and encouraged them to visit their physician or a pharmacy in order to provide the data. As a final option, we offered them a home visit. Both families and physicians were reimbursed for returning the respective questionnaire (50 and 25€, respectively).

Child factors

Since the results regarding the factors that influence the attrition rate in clinical trials are inconsistent, we analyzed a wide range of child and parental factors. All data with the exception of the child’s self-efficacy are based on parent reports. The health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was measured with the KID-KINDL-R [20]. The total score (including the 4 subscales ‘psychological well-being’, ‘self-esteem’, ‘family’ and ‘peers’) revealed an acceptable reliability value (α = .85) comparable with the original form (α = .70 [21]). The child’s weight-related quality of life (WRQoL) was measured with an established German instrument [22]. In line with previous validation values (α = .87 [23]), the reliability was good (α = .85). In addition, parents reported on the child’s food intake pertaining to ‘problematic’ (e.g., sweets, salty snacks, fast food and soft drinks) and ‘healthy’ (fruits, vegetables) food items on a 5-point scale (“never” – “several times a day”). Latent structure models confirmed the postulated factor structure [24]. The child’s eating behavior was measured with the FKE-KJ [22], which combines the 2 subscales ‘speed of eating’ (4 items) and ‘family eating environment’ (4 items). In accordance with previous evaluations, both scales showed an acceptable reliability within the current sample (α = .77 and .70, respectively). Furthermore, the child’s activity level, including media consumption and physical exercise, was assessed with an instrument from the KIGGS-study [25]. The instrument includes the mean duration (in hours) of the child’s use of television, video or computers as well as physical activity assessed by a 5-point Likert-scale. We formed a summarized score indicating the overall media consumption and activity level during an entire week. The child’s psychosocial strain was measured with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire SDQ [26]. The sum score is made up of four subscales: ‘emotional problems’, ‘behavioral problems’, ‘peer problems’ and ‘hyperactivity’. The scale showed good reliability (α = .84). Children assessed their own weight-related self-efficacy, answering the GW-SW-KJ [22], which includes 24 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Previous reliability values (α = .89) were replicated in the current study (α = .89). All scales were transformed to a 0–100 scale.

Parental aspects

Parental quality of life was measured by the well-established SF12 [27], including physical and mental well-being. The parents’ perception of their support of their child was measured with a self-constructed instrument including aspects such as being a role model, and emotional and instrumental support. The postulated factor structure was confirmed [24], showing acceptable reliability values for the summarized scale (α = .80). The parental self-efficacy in changing family eating and activity habits even in the face of problems or challenges was measured by a further self-constructed scale that includes aspects of care-taking, personal changes made and social demands. The Cronbach’s α indicated a high reliability of the scale (α = .95).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0. Attrition was defined as missing objective weight data at the 6- or 12-month follow-up. In the first step, we analyzed univariate differences between completers and non-completers (Chi-square, (M)ANOVA) and in the second step, we used logistic regression analysis to explore the variables that were associated with a higher risk of quitting the study on a multivariate level. For the logistic regression, variables were included stepwise: (1) demographic and inpatient stay-related aspects, (2) parental aspects, (3) the child’s psychosocial strain, and (4) secondary treatment outcomes, such as the child’s quality of life and self-efficacy, as well as activity level, food intake and eating behavior.

Results

At the end of the intervention, the data of one child could not be obtained. Therefore, only the data from 522 children were available. Complete weight and height data were available for 259 (49.6 %) children at the 6-month follow-up and for 350 (67.0 %) at the 12-month follow-up.

Differences between completers and non-completers

Univariate differences between completers and non-completers at the 6-month follow-up are presented in Table 2. The children’s initial weight status and weight change during the inpatient stay differed significantly between completers and non-completers, indicating a higher initial weight status and a lower weight loss in non-completers.

These differences between completers and non-completers at the 6-month follow-up were also observed in the one-year follow-up (see Table 3). In addition, there were significant differences regarding the parents’ educational level (completers had a higher level of education than non-completers) and parental support (completers reported more support for their child than non-completers), as well as the child’s psychosocial strain (completers reported less psychosocial strain than non-completers), the child’s WRQoL (completers reported higher scores than non-completers), and family eating environment (completers reported higher scores than non-completers).

Drop-out rates 6 and 12 months after the intervention

The logistic regression to predict those families that missed the weight and height measurement explained 16 % of the variance after 6 months and 14 % after 12 months. It was also able to predict 60 % of the sample correctly after 6 months and 67 % after 12 months. At the 6-month follow-up, participation in the intervention group (odds ratio (OR)) = 0.60) and having older parents (OR = 0.95) was associated with a lower risk of dropping out, whereas a lower weight loss during the inpatient stay was associated with a higher risk (OR = 24.05). After 12 months, higher parental educational level (OR = 0.81) and a more structured family eating environment (OR = 0.97) were associated with a lower risk of dropping out. Table 4 shows the results for the 12-month follow-up.

Discussion

Attrition is a highly relevant and prevalent problem in pediatric weight management trials. In the current study, we observed an attrition rate of 33.0 % at the 12-month follow-up. Our results are in line with those reported in the literature [3, 5, 7]. A recent review reported higher attrition rates in studies that focused on children with overweight or obesity (79.6 %) as well in long-term studies (74 %) [28]. Based on the results of a previous study assessing parental factors which might impede or facilitate their participation [29],8 we assumed time and financial constraints to be important. Therefore, we used an expensive and time-consuming method (re-sending questionnaires and reminder postcards, repeated telephone calls, offering home visits and financial incentives). These strategies were considered as successful retention strategies to facilitate parents’ participation and receive the long-term data [30]. We assume that this strategy did at least pay off a little, since we invested the greatest efforts before the second follow-up and the attrition rate at 12 months was slightly lower than that at the 6-month follow-up. Nevertheless, the attrition rate was high, and retention rates fell below our expectations. Further studies are needed to indicate empirically validated retention strategies. In order to enhance study commitment and decrease attrition, the study by Germann et al. [31] used an orientation session to give information about achievable and healthy weight loss. We agree that this might be helpful in decreasing the number of unsuccessful weight loss attempts, but it also excludes many individuals with weight problems and focuses only on highly motivated patients. Further research is needed on how to increase the retention rate in clinical trials, especially when not only self-reports but also physiological measurements are required [28].

BMI at baseline and weight loss during intervention are often reported to influence the drop-out in obesity interventions. With respect to the baseline BMI, we observed a higher drop-out rate in families whose children were heavier at baseline [4, 6]. In line with other reports [4, 5, 10], a lower initial weight loss increased the risk of not returning the follow-up assessments in our study. However, analyzing the variables in a multivariate model, only weight loss during intervention remained significant in terms of predicting drop-out at the 6-month follow-up, whereas at the 12-month follow-up, neither the baseline weight status nor the initial weight loss was relevant for individual attrition. Moreover, only at the short-term follow-up did drop-out rates differ between treatment groups, with parents in the intervention group seemingly more willing to return the follow-up data. This group took part in a weekend seminar, which stressed the important role of the parents in supporting their child. Since the two treatment groups did not differ in terms of BMI-SDS, this observation is not merely an effect of treatment effectiveness.

Previous research results concerning the socio-demographic data were controversial. We observed no influence from the child’s age, which contradicts the results of two other studies [4, 5]. Consistent with the literature, no effects of gender were observed [4, 5, 7, 8]. In our study, parents’ age influenced the retention rate for the short-term follow-up, an effect that was no longer visible 6 months later. Only at the 12-month follow-up was a higher level of parents’ education associated with a higher retention rate. We are aware of only one study in the field of pediatric weight management that reported similar results, even if only as tendencies [17]. With regard to psychological characteristics, the available evidence is sparse. In line with our observation regarding the differences between completers and non-completers, McCallum et al. [6] indicated that those who dropped out reported a lower quality of life for children. In addition, we found more psychological problems reported by the parents in the drop-out group. This concurs with the findings, with respect to prematurely stopping the intervention [10, 13, 17]. However, the reported differences in psychological characteristics in this study were not independent predictors in the multivariate logistic regression.

Further aspects that differ between the groups were the eating environment, in which a low degree of family meal structure remained a significant predictor for attrition at 12 months after intervention. The influence of the family eating environment may be interpreted as sign of a successful change in family habits – a major goal in pediatric weight loss interventions [32, 33]. In addition, studies from family-oriented intervention approaches suggest that parents play a key role in sustaining the treatment effect at the long-term follow-up [34, 35]. Our results are further supported by the data of other reports that stress parental influence in treatment adherence [10, 17].

Our study is limited in several ways. First, we could not assess any data at the follow-up measurements concerning the reasons for discontinuing the study. Some participants reported that when called by phone, they lost interest and that completing the questionnaires was too time-consuming. This is in line with the data reported by Savoye et al. [8]. and with our previous study [29]. In addition, our analyses were exploratory and we included many variables. We decided to take that path in order to not miss relevant features, and were willing to accept the increased risk of overestimating the clinical significance of the results. Furthermore, we also ran multivariate analyses in order to combat alpha error inflation. When interpreting our results in terms of comparing the pattern of short- and long-term follow-up data, it should be noted that we invested much more effort in gathering long-term data. Especially at the 12-month follow-up, we successfully contacted those parents who had simply forgotten to fill in the questionnaires due to time constraints or other priorities. Thus, we were able to observe differences otherwise obscured by organizational problems reported by the majority of parents [8].

An important strength of our study is that we collected data from a highly diverse and representative sample of participants, rather than only including those families with a higher level of education or income. Moreover, the weight data were based on blind assessment, thus decreasing the risk of underreporting weight status (see self-reported measurements) [36].

Conclusions

Our study results suggest that the strategies to reduce the attrition rate, which we employed after the first follow-up, were successful, but still could not prevent a final attrition rate of over 33 % for the second follow-up.

We were able to replicate differences between completers and non-completers found in previous studies. However, we observed a different pattern of predictors between the short-term (6 months) and long-term (12 months after intervention) follow-ups. De Niet et al. [10] also found different predictors for attrition at different stages of treatment. Whereas at the 6-month follow-up, mainly aspects associated with the intervention (randomization in the intervention group and initial weight loss) predicted the retention, at the 12-month follow-up, only family aspects such as educational level and family eating environment remained predictive. These differences indicate the risks inherent in only including a short-term follow-up, which might be biased in terms of success rates – especially when drop-out rates are high. Taking into account that in particular, short-term success in weight management does not necessarily imply positive long-term results, intervention studies should include longer follow-up periods and report their results on the basis of intention-to-treat analyses.

Abbreviations

- 95 % CI:

-

Confidence interval

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BMI-SDS:

-

Body mass index - standard deviation score

- CG:

-

Control group

- df:

-

Degrees of freedom

- EPOC:

-

Empowering parents of obese children

- Exp(B):

-

Odds ratio

- F:

-

Statistical test value

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- IG:

-

Intervention group

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- p:

-

Significance value

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- Wald:

-

Statistical test

- WRQoL:

-

Weight-related quality of life

- η2:

-

Explained variance

References

Ahern K. Methodological issues in the effects of attrition: simple solutions for social scientists. Field Methods. 2005;17:53–69.

Karlson CW, Rapoff MA. Attrition in randomized controlled trials for pediatric chronic conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:782–93.

Collins CE, Warren J, Neve M, McCoy P, Stokes BJ. Measuring effectiveness of dietetic interventions in child obesity: A systematic review of randomized trials. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:906–22.

Golley RK, Magarey AM, Baur LA, Steinbeck KS, Daniels LA. Twelve-month effectiveness of a parent-led, family-focused weight-management program for prepubertal children: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2007;119:517–25.

van den Akker EL, Puiman PJ, Groen M, Timman R, Jongejan MT, Trijsburg W. A cognitive behavioral therapy program for overweight children. J Pediatr. 2007;151:280–3.

McCallum Z, Wake M, Gerner B, Baur LA, Gibbons K, Gold L, Gunn J, Harris C, Naughton G, Riess C, Sanci L, Sheehan J, Ukoumunne OC, Waters E. Outcome data from the LEAP (Live, Eat and Play) trial: a randomized controlled trial of a primary care intervention for childhood overweight/mild obesity. Int J Obes. 2007;31:630–6.

Hughes AR, Stewart L, Chapple J, McColl JH, Donaldson MD, Kelnar CJ, Zabihollah M, Ahmed F, Reilly JJ. Randomized, controlled trial of a best-practice individualized behavioral program for treatment of childhood overweight: Scottish Childhood Overweight Treatment Trial (SCOTT). Pediatrics. 2008;121:e539.

Savoye M, Nowicka P, Shaw M, Yu S, Dziura J, Chavent G, O'Malley G, Serrecchia JB, Tamborlane WV, Caprio S. Long-term results of an obesity program in an ethnically diverse pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2011;127:402–10.

Skelton JA, Beech BM. Attrition in paediatric weight management: A review of the literature and new directions. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e273–81.

de Niet J, Timman R, Jongejan M, Passchier J, van den Akker E. Predictors of participant dropout at various stages of a pediatric lifestyle program. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e164.

Skelton JA, Goff DC, Ip E, Beech BM. Attrition in a multidisciplinary pediatric weight management clinic. Child Obes. 2011;7:185–93.

Jelalian E, Hart CN, Mehlenbeck RS, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Kaplan JD, Flynn-O'Brien KT, Wing RR. Predictors of attrition and weight loss in an adolescent weight control program. Obesity. 2008;16:1318–23.

Zeller MH, Saelens BE, Roehrig H, Kirk S, Daniels SR. Psychological adjustment of obese youth presenting for weight management treatment. Obes Res. 2004;12:1576–86.

Dolinsky DH, Armstrong SC, Ostbye T. Predictors of attrition from a clinical pediatric obesity treatment program. Clin Pediatr. 2012;51:1168–74.

Tershakovec AM, Kuppler K. Ethnicity, insurance type, and follow-up in a pediatric weight management program. Obesity. 2003;11:17–20.

Cote MP, Byczkowski T, Kotagal U, Kirk S, Zeller M, Daniels S. Service quality and attrition: an examination of a pediatric obesity program. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16:165–73.

Braet C, Jeannin R, Mels S, Moens E, van Winckel M. Ending prematurely a weight loss programme: the impact of child and family characteristics. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2010;17:406–17.

Warschburger P, Kröller K, Haerting J, Unverzagt S, Egmond-Frohlich A van: Empowering parents of obese children (EPOC): A randomized-controlled trial on additional long-term weight effects of a parent training. Appetite. 2016;103:148–56.

Kromeyer-Hauschild K, Wabitsch M, Kunze K, Geller F, Hesse V, von Hippel A, Jaeger U, Johnsen D, Korte W, Müller G, Müller JM, Niemann-Pilatus A, Remer T, Wittchen H, Zabransky S, Zellner K, Ziegler A, Hebebrand J. Perzentile für den Body-mass-Index für das Kindes- und Jugendalter unter Heranziehung verschiedener deutscher Stichproben. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2001;149:807–18.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M. KINDL-R. Fragebogen zur Erfassung der gesundheitsbezogenen Lebensqualität bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Revidierte Form. Manual. 2000.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Redegeld M, Bauer CP, Mayer H, Stachow R, Kiosz D, van Egmond-Fröhlich B, Rempis R, Kraft D, Bullinger M. Lebensqualität chronisch kranker Kinder und Jugendlicher in der Rehabilitation. Z Med Psychol. 2005;14:5–12.

Warschburger P, Fromme C, Petermann F. Konzeption und Analyse eines gewichtsspezifischen Lebensqualitätsfragebogens für übergewichtige und adipöse Kinder und Jugendliche (GW-LQ-KJ). Z Klin Psychol Psychiatr Psychother. 2005;4:356–69.

Warschburger P, Fromme C, Petermann F. Gewichtsbezogene Lebensqualität bei Schulkindern: Validität des GW-LQ-KJ. Z Gesundheitspsychol. 2004;12:159–66.

Kröller K, Warschburger P. Maternal feeding strategies and child’s food intake: Considering weight and demographic influences using structural equation modeling. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:78.

Lampert T, Sygusch R, Schlack R. Nutzung elektronischer Medien im Jugendalter. Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2007;50:643–52.

Woerner W, Becker A, Friedrich C, Rothenberger A, Klasen H, Goodman R. Normierung und Evaluation der deutschen Elternversion des Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Felderhebung. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2002;30:105–12.

Bullinger M, Kirchberger I. SF-36 Fragebogen zum Gesundheitsszustand - Manual. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1998.

Cui Z, Seburg EM, Sherwood NE, Faith MS, Ward DS. Recruitment and retention in obesity prevention and treatment trials targeting minority or low-income children: a review of the clinical trials registration database. Trials. 2015;16:564.

Warschburger P, Richter M. Gesunde Ernährung und Bewegung: Was verhindert und erleichtert Müttern den Zugang zu Präventionsprogrammen? Aktuel Ernahrungsmed. 2009;34:88–94.

Schoeppe S, Oliver M, Badland HM, Burke M, Duncan MJ. Recruitment and retention of children in behavioral health risk factor studies: REACH strategies. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21:794–803.

Germann JN, Kirschenbaum DS, Rich BH. Use of an orientation session may help decrease attrition in a pediatric weight management program for low-income minority adolescents. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2006;13:169–79.

Golan M, Crow S. Targeting parents exclusively in the treatment of childhood obesity: Long-term results. Obes Res. 2004;12:357–61.

Warschburger P. Psychologische Aspekte der Adipositas. Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2011;54:562–9.

Germann JN, Kirschenbaum DS, Rich BH. Child and parental self-monitoring as determinants of success in the treatment of morbid obesity in low-income minority children. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:111–21.

Wrotniak BH, Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Roemmich JN. Parent weight change as a predictor of child weight change in family-based behavioral obesity treatment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:342–7.

Gorber SC, Tremblay M, Moher D, Gorber B. A comparison of direct vs. self-report measures for assessing height, weight and body mass index: A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2007;8:307–26.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the support of our cooperating clinics:

• Kinder-Reha-Klinik “Am Nicolausholz” Bad Kösen

• Charlottenhall Vorsorge und Rehabilitationsklinik für Kinder und Jugendliche Bad Salzungen

• Fachklinik Prinzregent Luitpold Scheidegg

• Edelsteinklinik Bruchweiler

• Spessart-Klinik Bad Orb

• Viktoriastift Bad Kreuznach

• Kinder- und Jugendklinik Gesundheitspark Bad Gottleuba

• Auguste-Viktoria-Klinik Bad Lippspringe

• AHG Klinik für Kinder und Jugendliche Beelitz-Heilstätten

Special thanks to Nadine Häusler for critical proofreading.

Funding

This study was funded by a DFG (German Research Foundation) grant (WA 1143/4-1; 4–2). The funding organization played no role in the design of the study and collection of the data, their analysis and interpretation and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be deposited in a repository (doi: 10.5281/zenodo.164417 ).

Authors’ contributions

PW steered the design of the study, drafted the initial version of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. KK performed the statistical analysis, drafted the initial version of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent to publish

Consent to publish is part of the ethics approval.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent to participate was obtained. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Potsdam on 19 May 2006. (no reference number)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Warschburger, P., Kröller, K. Loss to follow-up in a randomized controlled trial study for pediatric weight management (EPOC). BMC Pediatr 16, 184 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0727-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0727-2