Abstract

Background

There is no standard treatment recommended at category 1 level in international guidelines for subsequent therapy after cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor (CDK4/6) based therapy. We aimed to evaluate which subsequent treatment oncologists prefer in patients with disease progression under CDKi. In addition, we aimed to show the effectiveness of systemic treatments after CDKi and whether there is a survival difference between hormonal treatments (monotherapy vs. mTOR-based).

Methods

A total of 609 patients from 53 centers were included in the study. Progression-free-survivals (PFS) of subsequent treatments (chemotherapy (CT, n:434) or endocrine therapy (ET, n:175)) after CDKi were calculated. Patients were evaluated in three groups as those who received CDKi in first-line (group A, n:202), second-line (group B, n: 153) and ≥ 3rd-line (group C, n: 254). PFS was compared according to the use of ET and CT. In addition, ET was compared as monotherapy versus everolimus-based combination therapy.

Results

The median duration of CDKi in the ET arms of Group A, B, and C was 17.0, 11.0, and 8.5 months in respectively; it was 9.0, 7.0, and 5.0 months in the CT arm. Median PFS after CDKi was 9.5 (5.0–14.0) months in the ET arm of group A, and 5.3 (3.9–6.8) months in the CT arm (p = 0.073). It was 6.7 (5.8–7.7) months in the ET arm of group B, and 5.7 (4.6–6.7) months in the CT arm (p = 0.311). It was 5.3 (2.5–8.0) months in the ET arm of group C and 4.0 (3.5–4.6) months in the CT arm (p = 0.434). Patients who received ET after CDKi were compared as those who received everolimus-based combination therapy versus those who received monotherapy ET: the median PFS in group A, B, and C was 11.0 vs. 5.9 (p = 0.047), 6.7 vs. 5.0 (p = 0.164), 6.7 vs. 3.9 (p = 0.763) months.

Conclusion

Physicians preferred CT rather than ET in patients with early progression under CDKi. It has been shown that subsequent ET after CDKi can be as effective as CT. It was also observed that better PFS could be achieved with the subsequent everolimus-based treatments after first-line CDKi compared to monotherapy ET.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Approximately 70% of breast cancers are hormone receptor (HR) positive [1]. Endocrine-based treatments are recommended in advanced HR-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her2)-negative breast cancer without visceral crisis [2, 3]. Progression-free survival (PFS) with monotherapy endocrine treatments was 10–14 months due to endocrine resistance [4]. One of the causes of endocrine resistance was the cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) pathway [4]. A significant PFS contribution of CDK inhibitors has been demonstrated in randomized clinical trials in which CDK4/6 inhibitors were used with endocrine therapies [5, 6]. With the results of these studies, the combination of CDK4/6 inhibitor (CDKi) and endocrine therapy has become the standard of care (SOC) in first-line and second-line therapy [2, 3]. Randomized clinical trials are still underway on which subsequent treatments will be used in patients with progressive disease under CDKi + endocrine therapy. The approximately 7-month progression-free survival obtained in phase 2 ByLieve study, which evaluated the efficacy of alpelisib in patients who had previously received CDKi-based therapy, indicated that alpelisib + fulvestrant might be effective in PIK3CA mutant patients [7]. For patients with progression under CDKi + endocrine therapy, there is currently no standard treatment recommended at category 1 level in international guidelines for subsequent therapy [3]. It is suggested that monotherapy endocrine treatments (fulvestrant or exemestane) or combinations with mTOR inhibitors can be preferred unless there is a visceral crisis. It is also stated that the alpelisib + fulvestrant combination is an option for patients with PIK3CA mutations [3].

In some retrospective studies, it has been observed that physicians prefer chemotherapy after CDKi treatment, even if there is no visceral crisis. In these studies, there was no significant PFS difference between chemotherapy and endocrine therapy. In this multicenter study, we aimed to evaluate which subsequent treatment oncologists prefer in patients with disease progression under CDKi. In addition, we aimed to show the effectiveness of systemic treatments after CDKi and whether there is a survival difference between hormonal treatments (monotherapy vs. mTOR-based).

Methods

This retrospective study was approved by local ethics committee. Fifty-three centers approved data submission for the study.

Patients with breast cancer aged 18 years or older and with estrogen or progesterone receptor levels ≥ 10% (CDK 4/6 inhibitors were reimbursed for only patients whose tumors expressed ≥ 10% estrogen receptor in our country) who have progressed after CDKi-based therapy and have received at least one systemic therapy (chemotherapy or endocrine-based therapy) were included in the study (between June 2018 and March 2022). Those who received CDKi treatment in early-stage disease and those with Her2 receptor positivity were excluded. Median PFS of the subsequent treatments after CDKi was the primary endpoint. Evaluation of the PFS difference between chemotherapy and endocrine-based treatments was the secondary endpoint.

Patients' age, menopausal status, date of diagnosis and date of metastasis, ECOG performance status, sites of metastasis, median duration of CDKi, treatments they received after CDKi, and dates of progression under treatment were recorded retrospectively from patient files or the hospital registry system. A total of 609 patients included in the study were evaluated in three groups: those who received CDKi on the first line (group A, n:202), those who received it on the second line (group B, n: 153), and those who received it on the ≥ 3rd line ( group C, n:254). Groups A, B, and C were also divided into those who received endocrine therapy (ET) and those who received chemotherapy (CT). The median PFS of the ET and CT groups were compared. In addition, the median PFS of ET was compared in all groups (A, B, C) as monotherapy versus everolimus-based combination therapy.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as median (range or interquartile range (IQR)), and categorical variables as frequency (percent). The Mann–Whitney-U test was used to compare the continuous variables of the two groups, and the chi-square or Fisher's Exact test was used to compare the categorical variables. The time from the start of the subsequent treatment after CDKi to disease progression or death was determined as PFS. Median follow-up time and PFS were determined by the Kaplan–Meier method. The log-rank test was used to determine the median PFS difference between the groups. All statistical analyzes were performed in two ways, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical features of patients at the onset of CDKi

The median age of patients in Groups A, B, and C was 54, 54, and 53, respectively, and the rates of patients ≥ 65 years were 21.3%, 20.3%, and 15.4%. The rates of patients with ECOG PS ≥ 2 were 6.4%, 4.0%, and 5.9% in Groups A, B, and C, respectively. The rates of bone-only metastatic patients in Groups A, B, and C were 36.1%, 37.3%, and 23.6%. The central nervous system (CNS) metastasis rate was 3.5%, 2.0%, and 5.5% in Groups A, B, and C, respectively (Table 1).

Clinical features of patients after CDKi

The median duration of CDKi in Group A was 10 months (range: 3–46). In group A, median CDKi was 17 months (range: 3–46 months) in the ET arm and 9 months (range: 2–39 months) in the CT arm. The median duration of CDKi in Group B was 9 months (range: 2–34). In group B, median CDKi was 11 months (range: 3–34 months) in the ET arm and 7 months (range: 2–20 months) in the CT arm. The median duration of CDKi in Group C was 5 months (range: 2–24). In group C, median CDKi was 8.5 months (range: 3–23 months) in the ET arm and 5 months (range: 2–24 months) in the CT arm. The rate of bone-only metastatic patients was 22.8%, 20.9%, and 12.6% in groups A, B, and C, respectively (Table 1).

Subsequent treatments after CDKi

In Group A after CDKi, 126 (62.4%) patients received CT, 76 (37.6%) ET; 110 (71.9%) CT, 43 (28.1%) ET in Group B; in Group C, 198 (77.9%) received CT and 56 (22.1%) ET (Fig. 1). The most frequently used chemotherapies in all three groups were capecitabine and taxane (Supp Table 1). Of the patients in group A who received ET, 4 received exemestane, 30 received fulvestrant, 32 received everolimus + exemestane, 4 received everolimus + fulvestrant, and 6 received Alpelisib + fulvestrant. In group B, 7 patients received exemestane, 9 received fulvestrant, 22 received everolimus + exemestane, and 5 received alpelisib + fulvestrant. In group C, 6 patients received exemestane, 11 received fulvestrant, 38 received everolimus + exemestane, and 1 received alpelisib + fulvestrant (Fig. 1).

Survival outcomes

Median follow-up was 6.2 months (95% CI: 4.6–7.9 months) in Group A, 7.5 months (95% CI: 5.7–9.5 months) in the ET arm, and 5.1 months (95% CI: 4.4–5.8 months) in the CT arm of group A. Median follow-up was 6.5 months (95% CI: 5.0–7.9 months) in Group B, 7.9 months (95% CI: 5.8–9.9 months) in the ET arm, and 5.3 months (95% CI: 4.7–5.9 months) in the CT arm of group B. Median follow-up was 7.5 months (95% CI: 6.7–8.4 months) in Group C, 7.6 months (95% CI: 6.2–8.9 months) in the ET arm, and 6.9 months (95% CI: 3.9–9.9 months) in the CT arm of group C.

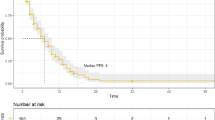

The subsequent median PFS after CDKi was 9.5 (5.0–14.0) months in the ET arm and 5.3 (3.9–6.8) months in the CT arm (p = 0.073) of group A. Median PFS was 6.7 (5.8–7.7) months in the ET arm and 5.7 (4.6–6.7) months in the CT arm (p = 0.311) of group B. Median PFS was 5.3 (2.5–8.0) months in the ET arm and 4.0 (3.5–4.6) months in the CT arm (p = 0.434) of group C (Fig. 1).

Clinical characteristics and survival outcomes of monotherapy and everolimus-based treatment groups

In Groups A, B, and C, the median duration of CDKi, median age, ECOG PS, and metastasis sites were similar in monotherapy and everolimus-based arms. The rate of denovo metastatic patients in the monotherapy arm of Group A was higher than in the everolimus-based arm (63.6% vs. 36.1%, p = 0.022).

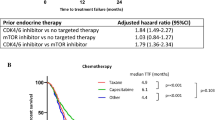

In Group A, the rate of patients who received ET in the adjuvant setting and relapsed in the first 24 months was higher in the monotherapy arm than in the everolimus-based arm (46.2% vs. 26.1%, p = 0.044) (Table 2). When patients who received ET after CDKi were compared as those who received everolimus-based combination therapy versus those who received monotherapy ET, the median PFS of everolimus-based and monotherapy arms in groups A, B, and C was 11.0 vs. 5.9 (p = 0.047) months, 6.7 vs. 5.0 (p = 0.164) months, and 6.7 vs. 3.9 (p = 0.763) months, respectively (Fig. 2A-C).

A. Progression free survival according to endocrine treatment in patients who take CDKi in first line. B. Progression free survival according to endocrine treatment in patients who take CDKi in second line. C. Progression free survival according to endocrine treatment in patients who take CDKi in ≥ 3rd line

Univariate PFS analysis of patients who received endocrine therapy after CDKi in the first line (n:70) was shown in Table 3. Age, ECOG PS, the median duration of CDKi, denovo metastasis, metastatic site, and disease-free interval did not affect PFS.

Safety data

Everolimus initiation dose was 10 mg/day. Dose reduction (to 5 mg) was performed in 19.1% of the patients. In the everolimus-based group, 42% of the patients had Grade 1 stomatitis, and 11% had Grade 2 stomatitis. There were no data on the use of primary dexamethasone prophylaxis for stomatitis. In the everolimus-based group, 15% of the patients had elevated AST or ALT, and 17% had arthralgia. In the monotherapy ET group, the most common adverse event was arthralgia, with a rate of 15%.

Any grade of adverse events occurred in 93% of patients receiving chemotherapy. 84% of patients who received CT had at least one dose reduction. The most common adverse events were neutropenia (47%), anemia (38%), and fatigue (33%). There was no patient who had discontinued CT due to toxicity.

Discussion

A standard of care treatment recommended as subsequent therapy in patients with advanced HR + , Her2- breast cancer that has progressed under CDKi therapy has not yet been established. Results of ongoing randomized clinical trials are awaited. Therefore, real-life data of retrospective studies is crucial. In our study, the factors affecting subsequent treatment choices and the effectiveness of these treatments were evaluated. In this multicenter retrospective study, it was observed that the short duration of CDKi in patients with HR + Her2- advanced breast cancer that progressed under CDKi treatment increased physicians' preference for CT in subsequent treatment. There was no difference in PFS between the subsequent CT and ET arms. When endocrine-based treatments were compared as monotherapy vs. everolimus-based treatments among patients who received CDKi in first-line, longer PFS was found with everolimus-based treatments.

In a study evaluating the factors affecting treatment choices (CT vs. ET) after CDKi, priority ET was preferred as subsequent therapy in patients who received CDKi in the first line, and priority CT was preferred in those who received CDKi in the second line [8]. As a result of the multivariate analysis performed in the same study, young age and short duration of CDKi were independent factors predicting CT preference [8]. In our study, physicians preferred CT for subsequent treatment in patients with a short duration of CDKi use.

PALOMA 3, a randomized clinical trial comparing fulvestrant vs. fulvestrant + palbociclib in previously treated patients with advanced breast cancer, showed no difference in duration of treatment between subsequent CT and ET after palbociclib (5.6 vs. 4.3 months) [9]. Similarly, retrospective analyzes of TREND, a phase2 study, showed no difference in duration of treatment between subsequent CT and ET (4.6 vs. 3.7 months), regardless of palbociclib use [10]. A retrospective study evaluating subsequent treatments after palbociclib found no significant difference in subsequent PFS between CT and ET, regardless of the palbociclib line [11]. The number of patients evaluated in Xi et al.'s study was limited [11]. For example, there were seven patients in both CT and ET arms after the first line of palbociclib [11]. The median duration of palbociclib in the first line was 20.7 months, similar to PALOMA3 [11]. The median PFS was 17 months in patients (n = 7) who received ET after the first line. The median duration of palbociclib in the second line was 12.8 months. In this setting, the median PFS of subsequent ET (n = 9) was 9.3 months, and CT (n = 14) was 4.7 months [11]. The subsequent PFS of patients who received palbociclib at the third or more line was 4.2 months in the ET arm (n = 16) and 4.1 months in the CT arm (n = 49) [11]. Similarly, in our study, the PFS of those who received subsequent CT and ET was 5.3 vs. 9.5, 5.7 vs. 6.7, and 4.0 vs. 5.3 months, respectively, in patients who received first, second, and ≥ 3rd line CDKi, and no statistical difference was found. In our study, short PFS obtained with subsequent treatments after the first line was associated with a short median duration of CDKi. The short use of the median CDKi indicated a relatively poor prognostic patient population in this study.

It was demonstrated in the BOLERO-2 study that the everolimus + exemestane combination achieved longer PFS than monotherapy exemestane [12]. In this study, 54% of the included patients received at least three lines of therapy [12]. The median PFS of the everolimus + exemestane combination was 6.9 months according to the local investigator's evaluation and 10.6 months according to the central investigator's evaluation [12]. At the time of the study, CDKi was not yet in use [12].

Contradictory results were obtained from limited retrospective studies showing the efficacy of everolimus-based treatments after CDKi [13,14,15]. In the study by Rozenblit et al., the median time to next treatment (TTNT) of those who received everolimus + exemestane who progressed under one line of monotherapy ET was longer than those who had disease progression under CDKi + ET (6.2 vs. 4.4 months, p = 0.03) [13]. Another small retrospective study evaluating everolimus-based therapy after palbociclib found a median PFS of 4.2 months [14]. However, 83% of the 41 patients included in this study consisted of patients who received at least three lines of treatment (heavy treatment) [14]. In a retrospective study comparing the efficacy of everolimus + exemestane in CDK-naive (n = 26) and CDK-received (n = 17) patients, median PFS was 4.2 vs. 3.6 months [15]. The authors suggested that the efficacy of everolimus + exemestane was not affected by CDKi [15]. In the same study, it was also noted that the median duration of CDKi was short (median CDKi duration of 10.3 months) [15]. In our study, among patients who received CDKi in first-line, those who received subsequent everolimus-based therapy had longer PFS than those who received monotherapy ET (11.0 vs. 5.9 months). The data obtained from these studies support that the mTOR/AKT/PI3K pathway, one of the many resistance mechanisms against CDKi, may be a target for subsequent therapies.

Our study had some limitations. The main limitations were that the study was retrospective, and the median duration of CDKi and follow-up were short. More patients received CT in the subsequent treatment than those who received ET. In addition, the shorter median duration of CDKi in patients who received CT compared to ET suggested that this group might have a relatively poor prognosis. The difference in median duration CDKi may have caused bias in the results obtained by comparing the CT and ET groups. The short median duration of CDKi could also affect subsequent PFS. Another limitation was that the rate of patients with disease progression in the first 24 months after adjuvant ET was lower in those receiving everolimus-based therapy than those receiving monotherapy ET. Despite these limitations, the investigation of the efficacy of subsequent treatments after CDKi with a large patient population (n = 609) was the strength of our study.

Conclusion

It was observed that oncologists preferred CT rather than ET in patients whose disease progressed in a short time with CDKi. This study showed that subsequent ET could be as effective as CT in patients whose disease progressed under ET + CDKi treatment. In addition, better PFS could be obtained with the subsequent everolimus-based therapy than with monotherapy ET after first line CDKi.

Availability of data and materials

The database of the study is available in the corresponding author and will be sent when requested by e-mail.

Change history

27 February 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10662-3

Abbreviations

- CDK:

-

Cyclin-dependent kinase

- CDKi:

-

Cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CT:

-

Chemotherapy

- ECOG PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status

- ET:

-

Endocrine treatment

- HR:

-

Hormone receptor

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

References

Colditz GA, Rosner BA, Chen WY, Holmes MD, Hankinson SE. Risk factors for breast cancer according to estrogen and progesterone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(3):218–28.

Gennari A, André F, Barrios C, Cortés J, De Azambuja E, DeMichele A, et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer☆. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(12):1475–95.

Gradishar WJ. NCCN Guidelines Updates: Management of Patients With HER2-Negative Breast Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(5.5):561–5.

Karacin C, Ergun Y, Oksuzoglu OB. Saying goodbye to primary endocrine resistance for advanced breast cancer? Med Oncol. 2021;38(1):1–2.

Hortobagyi GN, Stemmer SM, Burris HA, Yap Y-S, Sonke GS, Paluch-Shimon S, et al. Ribociclib as first-line therapy for HR-positive, advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1738–48.

Finn RS, Martin M, Rugo HS, Jones S, Im S-A, Gelmon K, et al. Palbociclib and letrozole in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(20):1925–36.

Rugo HS, Lerebours F, Ciruelos E, Drullinsky P, Ruiz-Borrego M, Neven P, et al. Alpelisib plus fulvestrant in PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer after a CDK4/6 inhibitor (BYLieve): one cohort of a phase 2, multicentre, open-label, non-comparative study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(4):489–98.

Princic N, Aizer A, Tang DH, Smith DM, Johnson W, Bardia A. Predictors of systemic therapy sequences following a CDK 4/6 inhibitor-based regimen in post-menopausal women with hormone receptor positive, HEGFR-2 negative metastatic breast cancer. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(1):73–80.

Masuda N, Mukai H, Inoue K, Rai Y, Ohno S, Ohtani S, et al. Analysis of subsequent therapy in Japanese patients with hormone receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer who received palbociclib plus endocrine therapy in PALOMA-2 and-3. Breast Cancer. 2021;28(2):335–45.

Rossi L, Biagioni C, McCartney A, Migliaccio I, Curigliano G, Sanna G, et al. Clinical outcomes after palbociclib with or without endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor positive and HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer enrolled in the TREnd trial. Breast Cancer Res. 2019;21(1):1–7.

Xi J, Oza A, Thomas S, Ademuyiwa F, Weilbaecher K, Suresh R, et al. Retrospective analysis of treatment patterns and effectiveness of palbociclib and subsequent regimens in metastatic breast cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(2):141–7.

Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, Burris HA III, Rugo HS, Sahmoud T, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(6):520–9.

Rozenblit M, Mun S, Soulos P, Adelson K, Pusztai L, Mougalian S. Patterns of treatment with everolimus exemestane in hormone receptor-positive HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer in the era of targeted therapy. Breast Cancer Res. 2021;23(1):1–10.

Dhakal A, Antony Thomas R, Levine EG, Brufsky A, Takabe K, Hanna MG, et al. Outcome of everolimus-based therapy in hormone-receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer patients after progression on palbociclib. Breast Cancer: Basic and Clinical Research. 2020;14:1178223420944864.

Cook MM, Al Rabadi L, Kaempf AJ, Saraceni MM, Savin MA, Mitri ZI. Everolimus Plus Exemestane Treatment in Patients with Metastatic Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer Previously Treated with CDK4/6 Inhibitor Therapy. Oncologist. 2021;26(2):101–6.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Turkish Oncology Group (TOG) - Breast Cancer Consortium.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CK, and BO, SP designed the study. CK, and BO wrote the manuscript. CK made the statistical analysis. All other authors collected data and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study approved by Ethical Committee of UHS Dr Abdurrahman Yurtaslan Ankara Oncology Training and Research Hospital. Due to retrospective nature of the study, UHS Dr Abdurrahman Yurtaslan Ankara Oncology Training and Research Hospital Ethical Committee waived off the informed consent in our study. All methods/ protocols were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: The family name of author Enes Erul has been corrected.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: TableS1.

Chemotherapy regimens.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Karacin, C., Oksuzoglu, B., Demirci, A. et al. Efficacy of subsequent treatments in patients with hormone-positive advanced breast cancer who had disease progression under CDK 4/6 inhibitor therapy. BMC Cancer 23, 136 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10609-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10609-8