Abstract

Background

Early detection and appropriate treatment of precancerous, mucosal changes could significantly decrease the prevalence of life-threatening gastric cancer. Biopsy of the normal-appearing mucosa to detect Helicobacter pylori and these conditions is not routinely obtained. This study assesses the prevalence and characteristics of H. pylori infection and precancerous conditions in a group of patients suffering from chronic dyspepsia who were subjected to gastric endoscopy and biopsy mapping.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included dyspeptic patients, not previously treated for H. pylori, undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with their gastric endoscopic biopsies obtained for examination for evidence of H. pylori infection and precancerous conditions. Demographic and clinical data on the gender, smoking, opium addiction, alcohol consumption, medication with aspirin, corticosteroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and family history of cancer were collected by interviewing the patients and evaluating their health records. The cohort examined consisted of 585 patients with a mean (SD) age of 48.0 (14.46) years, 397 (67.9%) of whom were women.

Results

H. pylori infection was identified in 469 patients (80.2%) with the highest prevalence (84.2%) in those aged 40–60 years. Opium addiction correlated with a higher a H. pylori infection rate, while alcohol consumption was associated with a lower rate by Odds Ratio 1.98 (95% CI 1.11–3.52) and 0.49 (95% CI 0.26–0.92), respectively. The prevalence of intestinal metaplasia, gastric atrophy and gastric dysplasia was 15.2, 12.6 and 7.9%, respectively. Increased age, positive H. pylori infection, endoscopic abnormal findings and opium addiction showed a statistically significant association with all precancerous conditions, while NSAID consumption was negatively associated with precancerous conditions. For 121 patients (20.7% of all), the EGD examination revealed normal gastric mucosa, however, for more than half (68/121, 56.2%) of these patients, the histological evaluation showed H. pylori infection, and also signs of atrophic mucosa, intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in 1.7, 4.1 and 1.7%, respectively.

Conclusion

EGD with gastric biopsy mapping should be performed even in the presence of normal-appearing mucosa, especially in dyspeptic patients older than 40 years with opium addiction in north-eastern Iran. Owing to the high prevalence of precancerous conditions and H. pylori infection among patients with dyspepsia in parts of Iran, large-scale national screening in this country should be beneficial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer is still a major worldwide problem, ranking fifth for incidence and third for cancer-related mortality [1,2,3]. According to GLOBOCAN 2018, gastric carcinoma is the second most common cancer in Iran and the 5-year prevalence is 19.22 per 100,000 [2]. Chronic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia are considered precancerous conditions and they constitute the background, against which dysplasia and more serious histological changes may occur [4]. Intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma represents the final outcome of the inflammation–atrophy–metaplasia–dysplasia–carcinoma sequence [5]. Even though early recognition and treatment is possible, most cases are diagnosed at a late stage and thus a large number of patients diagnosed with gastric cancer die of the disease [1]. Early detection and treatment, primarily by endoscopy rather than invasive surgery, is recommended [6, 7].

Multiple risk factors have been linked to the multistep progression from precancerous conditions to gastric cancer [8,9,10]. Helicobacter pylori infection plays a pivotal role in this progression, and a recent meta-analysis indicates that testing and treating this infection when found is associated with a reduced incidence of gastric cancer [11, 12]. This indicates the importance of knowing the distribution and prevalence of H. pylori infections and precancerous conditions and related risk factors, including the strategies suitable for lowering the incidence of gastric cancer. Although this would clearly help to prevent gastric cancer, few studies on the incidence of gastric precancerous conditions and H. pylori infection have been published in Iran. However, Ajdarkosh et al. [13] have found prevalence of H. pylori infection, intestinal metaplasia, gastric atrophy and dysplasia in 64.5, 19.8, 12.8 and 3.2%, respectively, among chronically dyspeptic patients aged ≥40 years. They recommend upper endoscopy and gastric mapping sampling in intermediate-risk to high-risk areas. Another study in Ardabil province [14], which has a high rate of gastric cancer, found that atrophic gastritis, reactive atypia and intestinal metaplasia are common in the antrum, corpus and cardia of the stomach and they therefore recommend endoscopic screening for precancerous conditions.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is commonly performed when evaluating patients with dyspepsia [15]. In many cases with normal-appearing mucosa, H. pylori and precancerous conditions can still be present in the stomach, and a reliable diagnosis is therefore important. In the absence of endoscopically visible lesions, biopsies from the stomach would contribute to diagnosing most H. pylori-related inflammatory and precancerous gastric lesions, which would be misdiagnosed without access to biopsies [16].

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) currently recommends biopsy even from normal appearing mucosa for the detection of H. pylori infection if previously unknown in the patient [15, 17]. However, to our knowledge, there are no clinical standards or guidelines for the performance of biopsies with respect to H. pylori and precancerous conditions of normal-appearing gastric mucosa in Iranian patients. The additional expense incurred by the need for obtaining and interpreting more biopsies from normal mucosa [18] may be cancelled out by the lower numbers of people developing gastric cancer. Early diagnosis of precancerous conditions and H. pylori infection would no doubt lead to an effective approach which would allow the early detection of gastric cancer, especially in high-risk areas like Iran. To that end, this study would assessed the prevalence and characteristics of H. pylori infection and precancerous conditions in patients with normal and abnormal-appearing mucosa undergoing EGD with dyspepsia as the sole indication.

Material and methods

Study summary

We conducted a cross-sectional study from 2015 to 2017 based on clinical data, bacterial findings and histological classification of the gastric mucosa in a set of patients with dyspepsia at the Gastroenterology Clinic of Emam Reza Hospital, a tertiary referral hospital affiliated with Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (MUMS). The inclusion/exclusion process was done as shown in Fig. 1.

Participants

During the three study years, patients aged > 18 years with dyspepsia, consistent with the Rome III criteria [19], which include one or more of postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain and/or burning, and thus eligible for EGD (n = 701), were enrolled. Patients were excluded if they had any history of partial/total gastrectomy or previous therapy for H. pylori infection. At this point, 16 patients opted out of the study for unknown reasons leaving 654 for the next step. However, EGD was only performed on 633 patients since 21 were unwilling to undergo the examination. A further 48 patients were excluded for various reasons (Fig. 1) resulting in 585 participants in the study.

Data gathering

Demographic data and clinical characteristics, including data on age, gender, past medical history (diabetes and hypertension in particular), tobacco use (daily smoking), alcohol use (daily drinker), opium addiction (daily user > 6 months), taking ≥500 mg of aspirin for > 1 month or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), family history of cancer (especially in first-degree relatives (FDRs) and/or second-degree relatives (SDRs) were collected by interviewing the patients and evaluating their health records before the EGD step.

Histopathology

Endoscopic biopsies were fixed in adequately buffered formalin (10%) overnight and subsequently routinely processed. All fragments were embedded in one paraffin block, multiple serial sections were obtained and all stained by routine hematoxylin/eosin and Giemsa stains. The slides were examined by two pathologists and in case of any diagnostic disagreement, other colleagues were asked to review the slides. Furthermore, macro-endoscopic features observed during the gastric inspection were also reviewed.

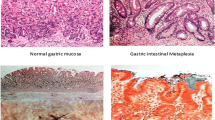

Precancerous conditions refer to a variety of conditions in which changes in stomach cells make them more prone into cancer. In our study, these included mucosal atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia and mucosa with abnormal gastric biopsy. Gastric atrophy is considered if there are loss of gastric glands, either together with pure (non-metaplastic) or associated with pyloric or intestinal metaplasia (metaplastic type). The degree of atrophy is graded as mild, moderate or severe; however, in this study, all types of atrophy was is considered regardless of severity. Gastric dysplasia, regarded as a combination of architectural atypia (glandular crowding, budding and branching) and cytologic atypia (cellular overlapping, hyperchromasia of the nuclei, pseudostratification, pleomorphism, dispolarity, increased mitosis and lack of surface maturation), was classified as adenomatous (intestinal) or foveolar (gastric). Regarding the extent of these changes, dysplasia was graded as low or high; however, all types of dysplasia were considered regardless of severity.

Expected outcomes

The primary focus was on finding precancerous conditions and H. pylori infection. A secondary focus was to evaluate potential associations between the histopathological examinations and the responses collected.

Statistical analysis

The chi square test was used to determine differences in the categorical variables. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to examine the degree of data normality, while T-test, ANOVA, Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to investigate the normality distribution of the data, i.e. to identify potential, significant differences between independent variables. Multivariable logistic regression analysis with backward stepwise model was used to ascertain the statistical significance of the association between precancerous conditions on the one hand and demographic data, clinical characteristics and H. pylori presence on the other. A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analyses were performed using SPSS statistics (version 20.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Demographic data, clinical characteristics including H. pylori status and histological patterns from the 585 patients (67.9% women) were analyzed (Table 1 and Table 2). The mean (±SD) age of the participants was 48.0 (±14.46) years. Also, 146 (25.0%) patients were addicted to opium or methamphetamine. Alcohol consumption was reported in 50 (8.5%) of the patients, while 173 (29.6%) regularly used NSAIDs and 88 (15.0%) aspirin. Histologic findings in endoscopic biopsies from the patients revealed that the prevalence of intestinal metaplasia, gastric atrophy and gastric dysplasia was 15.2, 12.6, and 7.9%, respectively. H. pylori infection rates were found in as many as 80.2% of the patients, with a particularly high prevalence among those aged 40–60 years. Opium addiction indicated higher H. pylori infection rates, while the situation was the opposite with respect to alcohol consumption (OR 1.98, %95 CI 1.11–3.52 and OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.26–0.92, respectively).

Based on multivariable logistic regression analysis, increased age and positive H. pylori infection indicated a significant association with precancerous conditions. In contrast, NSAID consumption showed a negative association with investigated outcomes (Table 3).

For 121 patients (20.7% of all), the EGD examination revealed normal gastric mucosa; however, for more than half (68/121–56.2%) of these patients, the histological evaluation showed H. pylori infection and also signs of atrophic mucosa, intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in 1.7, 4.1 and 1.7%, respectively.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the prevalence of advanced gastric conditions and related factors in north-eastern Iran. The study found a considerable prevalence of H. pylori infection, intestinal metaplasia, gastric atrophy and gastric dysplasia among the 585 study participants in the study area. Overall, our findings with respect to H. pylori infections and endoscopic abnormal findings and their association with older age are in line with other studies performed in Iran [20,21,22,23]. Importantly, some patients without visible endoscopic lesions turned out to have H. pylori infections and related precancerous conditions, which might have been missed without access to biopsies.

In our study, increased age and positive H. pylori infection indicated significant association with precancerous conditions. Given that dysplasia condition has been shown a high degree of progression to cancer, the association with dysplasia is more important compared to the other conditions. Consequently, it is necessary to apply endoscopic resection once high-grade dysplasia is observed. Although H. pylori eradication is advantageous when intestinal metaplasia is identified, follow-up endoscopic examinations should be considered in patients with intestinal metaplasia and in the older age range to detect more progressive conditions [24]. The findings also indicated that precancerous conditions could be found in normal-appearing mucosa. Considering that precancerous conditions may become stomach cancer, detecting them especially in dyspeptic patients older than 40 years with H. pylori infection and opium addiction is regarded as a high priority.

H. pylori infection rates are very high in different parts of Iran, with a prevalence rate ranging from 69 to 89%, and they do increase with age [25,26,27]. Population-based studies have reported that > 80% of adults aged ≥40 years are infected and that 64.5% of these infections occurred in dyspeptic patients [13]. Our study revealed a similar high rate (80.2%).

The pathogenesis of gastric cancer is multifactorial and associated with a degree of precancerous conditions [23, 28, 29]. Gastric atrophy, dysplasia, and intestinal metaplasia are considered the main precancerous conditions of the stomach and they develop, although slowly, during continuous H. pylori infection [30], that is therefore claimed to be a crucial risk factor of gastric cancer, especially outside the cardia [1]. The presence of precancerous conditions in dyspeptic patients in our study is in line with other studies in Iran but not as common as that reported by studies of Chinese and Asian cases [31,32,33]; however, it is more frequent than what is reported in western countries [34,35,36].

Although the gold standard for H. pylori detection is gastric biopsy, a study in Mashhad, Iran has shown detection of this infection in 698 out of 814 (85.75%) patients by the urea breath test (UBT) [37], which is just slightly higher than our results. In Ardabil, a high-risk region of gastric cancer in north-western Iran, histological results for H. pylori were found positive in almost 90% of the cases examined [14]. As exemplified by a report of 589 positive cases out of 736 (80.0%) examined dyspeptic patients in Mongolia, a country known for its high rates of gastric cancer mortality [38], this infection is indeed common.

The high prevalence of H. pylori infections in Iran is an important point due to the overwhelming evidence of a connection between this bacterium and cancer of the stomach. The mechanism involved seems have to do with H. pylori inducing over-expression of COX-2, a cyclooxigenase enzyme that catalyses the conversion of arachidonic acid into prostaglandins, higher levels of which have been found in gastric carcinoma and precancerous conditions [39, 40]. COX-2 expression is positively associated with histological status [41,42,43], and the COX-2/prostaglandin pathway induced by H. pylori almost certainly plays an important role in gastric carcinogenesis [44,45,46,47]. The drug celecoxib has been shown to inhibit both the flagellar movement and colonization of the H. pylori bacterium, and a recent population-based study reveals that treatment with this drug has beneficial effects on advanced gastric conditions [48]. Other studies have shown that the drug can significantly reduce the risk of cancer of the colon, lung, breast and prostate [49,50,51].

Screening and treatment of H. pylori should be encouraged, especially in north-eastern Iran as both H. pylori infection and gastric cancer are common in this region [52]. As found in the present study, it is important to consider presence of H. pylori infection in the stomach of dyspeptic patients even with normal macro-endoscopic results. That biopsies facilitate the diagnostic approach is further emphasized in a study showing H. pylori infection in 50% of normal-appearing gastric mucosa [24], and AGA recommends taking biopsies also of normal-appearing body and antrum of the stomach to explore this potential [15]. In consequence with this strong evidence, we feel that EGD alone is not sufficient for detecting all kinds of H. pylori-related inflammatory and precancerous gastric conditions in dyspeptic patients. However, studies on cost versus benefit of regularly adding biopsy studies are needed to complement current findings [53, 54].

The prevalence is affected by many factors, e.g., residency, ethnicity, age, socioeconomic aspects [55, 56], living conditions, lifestyle, hygiene status and industrialization [57,58,59]. Smoking is an independent risk factor for different types of gastrointestinal cancers and previous studies in Iran have revealed direct links between smoking and cancers [27, 60]. However, this study did not reach anywhere near statistical significance between smoking and precancerous stomach conditions; on the other hand, this could be due to the relatively low number of smokers in the cohort examined. Interestingly, regular use of NSAID was found to be negatively associated with appearance of this kind of conditions and so was aspirin but not at a significant level; again possibly due to the low number of regular aspirin takers in the cohort. A few cohort studies have also reported that NSAIDs consumption is associated with a reduced risk of gastrointestinal cancers, including gastric cancer [61, 62]. However, large-scale, clinical trials are needed to recommend it as protective for gastric cancer. The wider use of the drug celecoxib can also be contemplated, but here we need diagnosis before treatment. Indeed, the widespread use of drugs is fraught with unforeseen side effects and should not be advocated without strong backing evidence.

Two studies in Ardabil, a high-incidence gastric cancer province in Iran, revealed that opium use, water pipe inhalation and high salt intake are risk factors for this cancer [14, 63]. Also in our study, H. pylori infection was more common in patients addicted to opium. Further, opium addiction was more common in patients with intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia, although regression analysis revealed no significant association between them. The association between opium use and human cancer have been discussed for a long time with different mechanisms suggested. For example, there is some evidence that opium could increase the ethylation of DNA through reduction of N-nitrosamines and N-nitrosodimethylamine [64]. Also, it has been shown that opiates could work as cancer promoters by damaging human immune function, activating angiogenesis and tumour neovascularisation and also increasing N-nitrosamines and related materials by changing pharmacokinetics [64]. Furthermore, since addicted people often do not keep a personal high hygiene status, H. pylori infection may be more common among them. In spite of this collected evidence, a clear cause effect study is needed to confirm this association.

Our study had some limitations. First, Information about proton pump inhibitor (PPI) consumption was not available in this study. Some patients had previous use of PPI and some were frequently self-medicated, so they could not discontinue PPI for an adequate period before endoscopy. Although consistent with previous studies [65, 66] and AGA guidelines [15] we obtained biopsies both from antrum and body for the detection of H. pylori infection, but PPI consumption may reduce the colonization density of H. pylori and leads to false negative results at the histopathology assessment [67]. Second, the quantitative measurements of opium and alcohol abuse as well as use of NSAIDs and aspirin or other drugs were not addressed in the study. Furthermore, due to the high cost of pathology in our setting, we followed the AGA guidelines [15] and put all the samples together. Thus, it is not possible to classify according to the Sydney system, because in this system, a biopsy should be taken separately from body, antrum, and incisura. However, if precancerous conditions were found in the endoscopy surveillance, separate samples should be taken from different gastric locations. However, although this was not the aim of the current study, this kind of surveillance should be addressed by future studies. These limitations impose a lack of generalizability of the findings, but we still think it will be useful for low-and middle-income countries especially in the Middle East where there is a restriction of the resources available like in Iran.

Conclusion

This study shows that endoscopic biopsies, even from normal-appearing gastric mucosa, increase the chance of finding gastric cancer at the precancerous stage especially in patients infected with H. pylori. There is a well-supported connection between H. pylori infection and precancerous and cancerous conditions and as this infection is unusually common in parts of Iran, large-scale national screening may be beneficial. Finding patients at an early stage would save lives and reduce costs.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository, [https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RVQZDG].

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492 Epub 2018/09/13. PubMed PMID: 30207593.

Almasi Z, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Salehiniya H. Incidence, mortality, and epidemiological aspects of cancers in Iran; differences with the world data. J BUON. 2016;21(4):994–1004 Epub 2016/09/30. PubMed PMID: 27685925.

Goshayeshi L, Hoseini B, Yousefli Z, Khooie A, Etminani K, Esmaeilzadeh A, et al. Predictive model for survival in patients with gastric cancer. Electron Physician. 2017;9(12):6035–42. https://doi.org/10.19082/6035 Epub 2018/03/22. PubMed PMID: 29560157; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5843431.

Kapadia CR. Gastric atrophy, metaplasia, and dysplasia: a clinical perspective. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36(5 Suppl):S29–36; discussion S61-2. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004836-200305001-00006 Epub 2003/04/19. PubMed PMID: 12702963.

Carneiro F, Machado JC, David L, Reis C, Nogueira AM, Sobrinho-Simões M. Current thoughts on the histopathogenesis of gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2001;10(1):101–2. https://doi.org/10.1097/00008469-200102000-00013 Epub 2001/03/27. PubMed PMID: 11263582.

Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in the treatment of gastrointestinal superficial lesions: follow the guidelines! GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2015;22(5):184–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpge.2015.08.002 Epub 2015/09/27. PubMed PMID: 28868405; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5580126.

Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon T, Repici A, Vieth M, De Ceglie A, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47(9):829–54. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1392882 Epub 2015/09/01. PubMed PMID: 26317585.

Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process--first American Cancer Society award lecture on cancer epidemiology and prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52(24):6735–40 Epub 1992/12/15. PubMed PMID: 1458460.

Javid H, Soltani A, Mohammadi F, Hashemy SI. Emerging roles of microRNAs in regulating the mTOR signaling pathway during tumorigenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(7):10874–83 https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.28401.

Moafian Z, Maghrouni A, Soltani A, Hashemy SI. Cross-talk between non-coding RNAs and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in colorectal cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-021-06458-y.

Lee YC, Chiang TH, Chou CK, Tu YK, Liao WC, Wu MS, et al. Association between helicobacter pylori eradication and gastric cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(5):1113–24.e5. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.028 Epub 2016/02/03. PubMed PMID: 26836587.

Salmaninejad A, Valilou SF, Soltani A, Ahmadi S, Abarghan YJ, Rosengren RJ, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages: role in cancer development and therapeutic implications. Cell Oncol. 2019;42(5):591–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13402-019-00453-z.

Ajdarkosh H, Sohrabi M, Moradniani M, Rakhshani N, Sotodeh M, Hemmasi G, et al. Prevalence of gastric precancerous lesions among chronic dyspeptic patients and related common risk factors. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24(5):400–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/cej.0000000000000118 Epub 2015/03/21. PubMed PMID: 25793916.

Malekzadeh R, Sotoudeh M, Derakhshan MH, Mikaeli J, Yazdanbod A, Merat S, et al. Prevalence of gastric precancerous lesions in Ardabil, a high incidence province for gastric adenocarcinoma in the northwest of Iran. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57(1):37–42. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.57.1.37 Epub 2003/12/25. PubMed PMID: 14693833; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1770167.

Yang YX, Brill J, Krishnan P, Leontiadis G. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the role of upper gastrointestinal biopsy to evaluate dyspepsia in the adult patient in the absence of visible mucosal lesions. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(4):1082–7. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.039 Epub 2015/08/19. PubMed PMID: 26283143.

Lahner E, Esposito G, Zullo A, Hassan C, Carabotti M, Galli G, et al. Gastric precancerous conditions and helicobacter pylori infection in dyspeptic patients with or without endoscopic lesions. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51(11):1294–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2016.1205129 Epub 2016/07/22. PubMed PMID: 27442585.

Stolte M, Meining A. The updated Sydney system: classification and grading of gastritis as the basis of diagnosis and treatment. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15(9):591–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2001/367832 Epub 2001/09/27. PubMed PMID: 11573102.

Teriaky A, AlNasser A, McLean C, Gregor J, Yan B. The utility of endoscopic biopsies in patients with normal upper endoscopy. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:3026563. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/3026563.

Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Andrews CN, Enns RA, Howden CW, Vakil N. ACG and CAG clinical guideline: management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(7):988–1013. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2017.154 Epub 2017/06/21. PubMed PMID: 28631728.

Malekzadeh R, Derakhshan MH, Malekzadeh Z. Gastric cancer in Iran: epidemiology and risk factors. Arch Iran Med. 2009;12(6):576–83 Epub 2009/11/03. PubMed PMID: 19877751.

Malekzadeh MM, Khademi H, Pourshams A, Etemadi A, Poustchi H, Bagheri M, et al. Opium use and risk of mortality from digestive diseases: a prospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(11):1757–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2013.336 Epub 2013/10/23. PubMed PMID: 24145676; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5752100.

Mohebbi M, Mahmoodi M, Wolfe R, Nourijelyani K, Mohammad K, Zeraati H, et al. Geographical spread of gastrointestinal tract cancer incidence in the Caspian Sea region of Iran: spatial analysis of cancer registry data. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:137. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-8-137 Epub 2008/05/16. PubMed PMID: 18479519; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2397428.

Yavari P, Sadrolhefazi B, Mohagheghi MA, Madani H, Mosavizadeh A, Nahvijou A, et al. An epidemiological analysis of cancer data in an Iranian hospital during the last three decades. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9(1):145–50 Epub 2008/04/29. PubMed PMID: 18439094.

Sugano K. Premalignant conditions of gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(6):906–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.12209 Epub 2013/04/09. PubMed PMID: 23560829.

Cancer IAfRo. GLOBOCAN 2012: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. 2012.

Malekzadeh R. Effect of helicobacter pylori eradication on different subtypes of gastric cancer: perspective from a middle eastern country. Helicobacter Pylori Eradication Strategy Prev Gastric Cancer. 2014;8:55–60.

Rastaghi S, Jafari-Koshki T, Mahaki B, Bashiri Y, Mehrabani K, Soleimani A. Trends and risk factors of gastric cancer in Iran (2005–2010). Int J Prev Med. 2019;10.

Shin WG, Kim HU, Song HJ, Hong SJ, Shim KN, Sung IK, et al. Surveillance strategy of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia in a country with a high prevalence of gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(3):746–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-011-1919-0 Epub 2011/10/11. PubMed PMID: 21984437.

Vannella L, Lahner E, Annibale B. Risk for gastric neoplasias in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis: a critical reappraisal. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(12):1279–85. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i12.1279 Epub 2012/04/12. PubMed PMID: 22493541; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3319954.

Mera RM, Bravo LE, Camargo MC, Bravo JC, Delgado AG, Romero-Gallo J, et al. Dynamics of helicobacter pylori infection as a determinant of progression of gastric precancerous lesions: 16-year follow-up of an eradication trial. Gut. 2018;67(7):1239–46. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311685 Epub 2017/06/26. PubMed PMID: 28647684; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5742304.

Huang RJ, Ende AR, Singla A, Higa JT, Choi AY, Lee AB, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and surveillance patterns for gastric intestinal metaplasia among patients undergoing upper endoscopy with biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(1):70–7.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2019.07.038 Epub 2019/08/20. PubMed PMID: 31425693.

Choi CE, Sonnenberg A, Turner K, Genta RM. High prevalence of gastric preneoplastic lesions in east Asians and hispanics in the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(7):2070–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-015-3591-2 Epub 2015/03/01. PubMed PMID: 25724165.

McCracken M, Olsen M, Chen MS Jr, Jemal A, Thun M, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, and associated risk factors among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese ethnicities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(4):190–205. https://doi.org/10.3322/canjclin.57.4.190 Epub 2007/07/13. PubMed PMID: 17626117.

Cheli R, Giacosa A, Pirasso A. Chronic gastritis: a dynamic process toward cancer. Precursor Gastric Cancer N Y. 1984:117–29.

Falt P, Hanousek M, Kundrátová E, Urban O. Precancerous conditions and lesions of the stomach. Klin Onkol. 2013;26 Suppl:S22–8. https://doi.org/10.14735/amko2013s22 Epub 2014/01/17. PubMed PMID: 24325159.

Fennerty MB, Emerson JC, Sampliner RE, McGee DL, Hixson LJ, Garewal HS. Gastric intestinal metaplasia in ethnic groups in the southwestern United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1992;1(4):293–6 Epub 1992/05/01. PubMed PMID: 1303129.

Nakhaei MM. Prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection in patients with digestive complaints using urea breath test in Mashhad, Northeast Iran. J Res Health Sci. 2010;10(2):77–80 Epub 2010/01/01. PubMed PMID: 22911928.

Khasag O, Boldbaatar G, Tegshee T, Duger D, Dashdorj A, Uchida T, et al. The prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection and other risk factors among Mongolian dyspeptic patients who have a high incidence and mortality rate of gastric cancer. Gut Pathog. 2018;10:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-018-0240-2 Epub 2018/04/11. PubMed PMID: 29636824; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5883366.

Biramijamal F, Basatvat S, Hossein-Nezhad A, Soltani MS, Akbari Noghabi K, Irvanloo G, et al. Association of COX-2 promoter polymorphism with gastrointestinal tract cancer in Iran. Biochem Genet. 2010;48(11–12):915–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10528-010-9372-x Epub 2010/09/03. PubMed PMID: 20809087.

Liu D, He Q, Liu C. Correlations among helicobacter pylori infection and the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor in gastric mucosa with intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25(4):795–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06168.x Epub 2010/05/25. PubMed PMID: 20492336.

Walker MM. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in early gastric cancer, intestinal metaplasia and helicobacter pylori infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14(4):347–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00042737-200204000-00001 Epub 2002/04/11. PubMed PMID: 11943943.

Saukkonen K, Nieminen O, van Rees B, Vilkki S, Härkönen M, Juhola M, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in dysplasia of the stomach and in intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(7):1923–31 Epub 2001/07/13. PubMed PMID: 11448905.

Yamagata R, Shimoyama T, Fukuda S, Yoshimura T, Tanaka M, Munakata A. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression is increased in early intestinal-type gastric cancer and gastric mucosa with intestinal metaplasia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14(4):359–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/00042737-200204000-00004 Epub 2002/04/11. PubMed PMID: 11943946.

Ristimäki A, Honkanen N, Jänkälä H, Sipponen P, Härkönen M. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human gastric carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57(7):1276–80 Epub 1997/04/01. PubMed PMID: 9102213.

Kimura A, Tsuji S, Tsujii M, Sawaoka H, Iijima H, Kawai N, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and nitrotyrosine in human gastric mucosa before and after helicobacter pylori eradication. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fat Acids. 2000;63(5):315–22. https://doi.org/10.1054/plef.2000.0220 Epub 2000/11/25. PubMed PMID: 11090259.

Konturek PC, Rembiasz K, Konturek SJ, Stachura J, Bielanski W, Galuschka K, et al. Gene expression of ornithine decarboxylase, cyclooxygenase-2, and gastrin in atrophic gastric mucosa infected with helicobacter pylori before and after eradication therapy. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48(1):36–46. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1021774029089 Epub 2003/03/21. PubMed PMID: 12645788.

Kim N, Kim CH, Ahn DW, Lee KS, Cho SJ, Park JH, et al. Anti-gastric cancer effects of celecoxib, a selective COX-2 inhibitor, through inhibition of Akt signaling. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24(3):480–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05599.x Epub 2008/10/01. PubMed PMID: 18823436.

Wong BC, Zhang L, Ma JL, Pan KF, Li JY, Shen L, et al. Effects of selective COX-2 inhibitor and helicobacter pylori eradication on precancerous gastric lesions. Gut. 2012;61(6):812–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300154 Epub 2011/09/16. PubMed PMID: 21917649.

Sung JJ, Leung WK, Go MY, To KF, Cheng AS, Ng EK, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in helicobacter pylori-associated premalignant and malignant gastric lesions. Am J Pathol. 2000;157(3):729–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64586-5 Epub 2000/09/12. PubMed PMID: 10980112; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1885697.

Liu F, Pan K, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Ma J, et al. Genetic variants in cyclooxygenase-2: expression and risk of gastric cancer and its precursors in a Chinese population. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(7):1975–84. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.021 Epub 2006/06/10. PubMed PMID: 16762620.

Khorram MR, Goshayeshi L, Maghool F, Bergquist R, Ghaffarzadegan K, Eslami S, et al. Prevalence of mismatch repair-deficient colorectal adenoma/polyp in early-onset, advanced cases: a cross-sectional study based on Iranian hereditary colorectal cancer registry. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-020-00395-y Epub 2020/03/21. PubMed PMID: 32193764.

Pourhoseingholi MA, Najafimehr H, Hajizadeh N, Zali MR. Pattern of gastric cancer incidence in Iran is changed after correcting the misclassification error. Middle East J Cancer. 2020;11(1):91–8.

Bakhshayesh S, Hoseini B, Bergquist R, Nabovati E, Gholoobi A, Mohammad-Ebrahimi S, et al. Cost-utility analysis of home-based cardiac rehabilitation as compared to usual post-discharge care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2020:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779072.2020.1819239 Epub 2020/09/08. PubMed PMID: 32893713.

Azizi A, Aboutorabi R, Mazloum-Khorasani Z, Hoseini B, Tara M. Diabetic personal health record: a systematic review article. Iran J Public Health. 2016;45(11):1388–98 Epub 2016/12/30. PubMed PMID: 28032056; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5182247.

Hunt RH, Xiao SD, Megraud F, Leon-Barua R, Bazzoli F, van der Merwe S, et al. Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. World gastroenterology organisation global guideline. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20(3):299–304 Epub 2011/10/01. PubMed PMID: 21961099.

Montazeri M, Hoseini B, Firouraghi N, Kiani F, Raouf-Mobini H, Biabangard A, et al. Spatio-temporal mapping of breast and prostate cancers in South Iran from 2014 to 2017. 2020;20(1):1170. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07674-8 PubMed PMID: 33256668.

Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, et al. Global prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(2):420–9. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022 Epub 2017/05/01. PubMed PMID: 28456631.

Ali N, Jaffar A, Anwer M, Raza M, Ali N. The economic analysis of tobacco industry: a case study of tobacco production in Pakistan. Int J Res (IJR). 2015;2(3).

Kiani B, Hashemi Amin F, Bagheri N. Association between heavy metals and colon cancer: an ecological study based on geographical information systems in north-eastern Iran. 2021;21(1):414. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08148-1 PubMed PMID: 33858386.

Akhavan Rezayat A, Dadgar Moghadam M, Ghasemi Nour M, Shirazinia M, Ghodsi H, Rouhbakhsh Zahmatkesh MR, et al. Association between smoking and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. SAGE Open Med. 2018;6:2050312117745223. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312117745223 Epub 2018/02/06. PubMed PMID: 29399359; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5788091.

Lindblad M, Lagergren J, García Rodríguez LA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of esophageal and gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(2):444–50. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-04-0467 Epub 2005/03/01. PubMed PMID: 15734971.

Limburg PJ, Wei W, Ahnen DJ, Qiao Y, Hawk ET, Wang G, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, esophageal squamous cell cancer chemoprevention trial of selenomethionine and celecoxib. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(3):863–73. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.024 Epub 2005/09/07. PubMed PMID: 16143126.

Sadjadi A, Derakhshan MH, Yazdanbod A, Boreiri M, Parsaeian M, Babaei M, et al. Neglected role of hookah and opium in gastric carcinogenesis: a cohort study on risk factors and attributable fractions. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(1):181–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28344 Epub 2013/06/26. PubMed PMID: 23797606; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5821120.

Khademi H, Malekzadeh R, Pourshams A, Jafari E, Salahi R, Semnani S, et al. Opium use and mortality in Golestan cohort study: prospective cohort study of 50,000 adults in Iran. BMJ. 2012;344:e2502. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e2502 Epub 2012/04/19. PubMed PMID: 22511302; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3328545 www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Yakoob J, Jafri W, Abid S, Jafri N, Abbas Z, Hamid S, et al. Role of rapid urease test and histopathology in the diagnosis of helicobacter pylori infection in a developing country. BMC Gastroenterol. 2005;5:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230x-5-38 Epub 2005/11/29. PubMed PMID: 16309551; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1316874.

Dickey W, Kenny BD, McConnell JB. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on the detection of helicobacter pylori in gastric biopsies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10(3):289–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0953-0673.1996.00289.x Epub 1996/06/01. PubMed PMID: 8791953.

Shirin D, Matalon S, Avidan B, Broide E, Shirin H. Real-world helicobacter pylori diagnosis in patients referred for esophagoduodenoscopy: the gap between guidelines and clinical practice. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4(6):762–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050640615626052 Epub 2017/04/15. PubMed PMID: 28408993; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5386226.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mashhad University of Medical Sciences for its support.

Funding

This study was supported by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (grant number of 941480). The funder had no role in design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AE, LG, BH, and MBO contributed to the study design. All authors (AE, LG, RB, AF, AKh, LJ, HMM, AB, MBO, and BH) contributed to data gathering and interpretation of the results. LJ and BH performed analyses. BH, MBO, and LG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RB edited the final version of the manuscript. All authors (AE, LG, RB, AF, AKh, LJ, HMM, AB, MBO, and BH) read, commented, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (ethics code: IR.MUMS.fm.REC.1395.132). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Esmaeilzadeh, A., Goshayeshi, L., Bergquist, R. et al. Characteristics of gastric precancerous conditions and Helicobacter pylori infection among dyspeptic patients in north-eastern Iran: is endoscopic biopsy and histopathological assessment necessary?. BMC Cancer 21, 1143 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08626-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08626-6