Abstract

Background

Though the gut microbiome has been associated with efficacy of immunotherapy (ICI) in certain cancers, similar findings have not been identified for microbiomes from other body sites and their correlation to treatment response and immune related adverse events (irAEs) in lung cancer (LC) patients receiving ICIs.

Methods

We designed a prospective cohort study conducted from 2018 to 2020 at a single-center academic institution to assess for correlations between the microbiome in various body sites with treatment response and development of irAEs in LC patients treated with ICIs. Patients must have had measurable disease, ECOG 0–2, and good organ function to be included. Data was collected for analysis from January 2019 to October 2020. Patients with histopathologically confirmed, advanced/metastatic LC planned to undergo immunotherapy-based treatment were enrolled between September 2018 and June 2019. Nasal, buccal and gut microbiome samples were obtained prior to initiation of immunotherapy +/− chemotherapy, at development of adverse events (irAEs), and at improvement of irAEs to grade 1 or less.

Results

Thirty-seven patients were enrolled, and 34 patients were evaluable for this report. 32 healthy controls (HC) from the same geographic region were included to compare baseline gut microbiota. Compared to HC, LC gut microbiota exhibited significantly lower α-diversity. The gut microbiome of patients who did not suffer irAEs were found to have relative enrichment of Bifidobacterium (p = 0.001) and Desulfovibrio (p = 0.0002). Responders to combined chemoimmunotherapy exhibited increased Clostridiales (p = 0.018) but reduced Rikenellaceae (p = 0.016). In responders to chemoimmunotherapy we also observed enrichment of Finegoldia in nasal microbiome, and increased Megasphaera but reduced Actinobacillus in buccal samples. Longitudinal samples exhibited a trend of α-diversity and certain microbial changes during the development and resolution of irAEs.

Conclusions

This pilot study identifies significant differences in the gut microbiome between HC and LC patients, and their correlation to treatment response and irAEs in LC. In addition, it suggests potential predictive utility in nasal and buccal microbiomes, warranting further validation with a larger cohort and mechanistic dissection using preclinical models.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03688347. Retrospectively registered 09/28/2018.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

For carefully selected patients, the advent of immunotherapy opened promising avenues of treatment and expectations for improved survival. With it arose the challenges of managing its immune-related adverse effects (irAEs). Attention has shifted to increasing immunotherapy efficacy in addition to mitigating the development of irAEs [1].

Cancer propagation is largely a result of the body’s inability to destroy mutated cells bearing aberrant antigen signatures; the disease can be framed as dysregulation of patient immunity [2, 3]. The bacterial composition of the gut has been theorized to yield carcinomodulatory effects [4,5,6]. Early studies demonstrated that mice with bacteria-deplete gut microbiomes were less likely to develop cancer after compared to those with microbiome intact [7, 8]. Dysbiosis, similarly, has been linked to carcinogenesis [9]. Atopic pulmonary disorders have been linked to specific changes in the gut microbiome: this concept of “crosstalk” may also occur in extrapulmonary organ systems [5, 10,11,12,13,14]. Pivotally, in a recent study, genetically engineered mice were transplanted with bacteria provoking intrapulmonary IL-17 inflammatory changes and shown to facilitate the development of lung cancer [15].

The influence of the microbiome in chemotherapy and immunotherapy efficacy has been prolifically documented. Enteric manipulation of bacteria has been linked to altered treatment efficacy: antibiotic-treated mice exhibited blunted immune response to both immunotherapy and radiation therapy [16]. In mouse models, Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium have been implicated in enhancement of anti-CTLA-4 activation and response to anti-PD-L1 therapy [17,18,19]. In human patients, Akkermansia levels positively correlated with partial response or stable disease, and in mouse models, repletion of Akkermansia via oral gavage was able to repotentiate tumor response to CTLA-4 and PD-L1 therapy [20].

Less evidence exists to support the microbiome’s role in development of irAEs. Firmicutes enrichment has been associated with development of immune-related colitis following treatment with ipilimumab, whereas corresponding enrichment in Bacteroidetes was associated with fewer episodes of colitis [21]. Mice repleted with B. fragilis species were less likely to develop immune-related toxicities after exposure to anti-CTLA-4 inhibitors [18]. Taken together, these findings raise the question of a relationship between systemic and local microbiota in cancer – specifically, whether microbiome sites both local and distant could be correlated to pulmonary tumorigenesis, immunotherapy response or development of irAEs.

We designed a prospective study to address three specific questions. Our study compares microbiome composition between LC and HC residing in the same geographic area. Second, we will evaluate for longitudinal correlations in the microbiome of three separate body sites – gut, buccal, and nasal, the latter two chosen for their proximity to and possible predictive surrogacy for the respiratory tract. This surrogacy is of particular interest in lung cancer: though the microbiome in distant body sites were previously found not to correlate with immunotherapy response in melanoma patients [22], it remains paramount to ascertain whether the respiratory tract microenvironment correlates to immunotherapy response and toxicity for lung cancer, especially considering aforementioned evidence that respiratory tract bacteria can facilitate lung cancer progression [15]. Lastly, we will analyze for associations between the microbiome and tumor response to immunotherapy and/or development of irAEs.

Methods

Patients

Patients 18 years or older with histopathologically confirmed LC whose treatment regimens included immunotherapy, either as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy, were eligible for this study. Exclusion criteria included active pregnancy, active recreational drug or alcohol abuse, and localized disease that could be managed definitively with surgery.

Study design and treatments

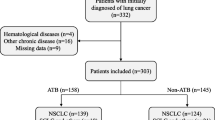

This prospective, single-center cohort pilot study was conducted at the University of Iowa Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center (HCCC) in Iowa, United States. The study was approved by the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics Institutional Review Board. Eligible patients visiting HCCC for LC treatment were screened, provided written informed consent, and enrolled in the study immediately prior to beginning immunotherapy or chemo-immunotherapy (Fig. 1a). Patients were enrolled between September 2018 and June 2019.

Description of patient cohorts and study schema. (a) Study schema showing the collection of microbiome samples from three separate body sites. Samples undergo 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing followed by taxonomic profiling. The resulting data is correlated to clinical outcomes such as response to ICI therapy or development of AEs. (b) An abbreviated demographics chart summarizing notable disease and patient characteristics of LC contributors. For granular individual characteristics, please refer to Supplemental Table 1. (c) Breakdown of patients belonging to each study cohort. ICI = immune checkpoint inhibitor. Checkpoint inhibitor status (number of patients enrolled – number of fecal samples that were unable to be analyzed or not submitted – number of nasal/buccal samples that were unable to be analyzed or not submitted

Patients were treated per guidelines for their disease subtype, overseen by participating oncologists whose subspecialty covered the patient’s primary diagnosis. Microbiome sample collection was triggered by the following events: (1) Prior to initiation of immunotherapy, (2) at the time immunotherapy was held due to concern for AE/irAE development, and (3) at improvement of AE/irAE severity to Grade 1 or less (Fig. 1c).

Assessments

Microbiome sampling, DNA extraction, sequencing and analyses

Microbiome control comparisons were obtained from 32 previously identified healthy patient samples stored in a separate repository for a prior study (Cherwin et al., Healthy Control for Microbiome, Cytokine, and Immunity Biomarker Analysis, IRB-01, The University of Iowa, #201902825).

At enrollment, nasal and buccal mucosal swabs, and fecal samples were obtained. If a fecal sample could not be obtained at enrollment, the patient received a stool collection kit to return the sample prior to beginning immunotherapy.

Fecal samples were collected using a Commode Specimen Collection System, oral samples were collected using saliva collection tubes (Access-genetics, Eden Prairie, MN) and nasal samples were collected using ESwab™ (Copan Diagnostic, Murrieta, CA). All samples were then stored at − 80 °C prior to processing. DNA was extracted from the fecal, oral and nasal samples using DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) 16S rRNA regions (V3–4) were amplified as previously described [23]. DNA library for sequencing was prepared for Illumina MiSeq; we used the Nextera XT Index kit to attach dual index adapters. Each library was prepared by diluting the samples to 5 ng/μL and equal volumes were mixed to 4 nM. We quantified the DNA concentration by Qubit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). We carried out the library preparations according to the 16S library preparation protocol of Illumina (Illumina, San Diego, Cam USA), and sequenced the libraries using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600 cycles) for 300-bp pair-ends.

Raw reads were quality-controlled, merged, and mapped to the 16S reference database (SILVA 13.2 [24]) using DADA2 [25] to generate OTU clusters. When running DADA2, the accepted amplicon lengths were set to between 240 and 260 bp (with parameter “truncLen”), followed by trimming the leading 15 bp low-quality region (with parameter “trimLeft”). Pair-end reads remaining after each stage of DADA2 are included in QC and Read Statistics. The average percent of remaining input reads (non-chimera) ranged from 68% in the nasal response cohort to 93% in the buccal toxicity cohort. The resulting OTU clusters were then analyzed using MicrobiomeAnalyst to compute α-diversity, β-diversity and assess differential abundance. When running MicrobiomeAnalyst [26], OTU count were first transformed into centered log ratio (CLR); taxa with little variance between conditions (the lower 0.5% quantile) were not considered because they are less informative in comparative studies (by setting the inter-quantile range to 0.5%). METAGENassist [27] was used to perform partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). Excepting adjustments mentioned above, default parameters for all programs were used across the entire study.

Fecal microbiome sequencing and analysis were initially conducted at the Iowa Institute of Human Genetics and confirmed separately at the University of Kansas. Nasal and buccal microbiome analysis was conducted at the University of Kansas.

Toxicity assessment

Toxicities/AEs were evaluated at time of patient presentation to clinic or in the event of acute hospitalization, documented by the treating oncologist in accordance with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. irAEs were defined as AEs consistent with an immune-mediated mechanism of action and requiring management with steroids or other immunosuppressants, and/or endocrine-targeted therapy for endocrinopathies [28, 29].

Response assessment

Patients were evaluated for response or progression via CT or PET/CT imaging. Imaging was obtained after 3 cycles’ therapy if the patient was treated with a single-agent regimen, and after 2 cycles with a doublet regimen. Responders were classified as patients who experienced complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) with a duration of at least 3 ~ 6 months after starting immunotherapy; those with stable or progressive disease were considered non-responders.

Results

Patient demographics

37 patients were consented between September 2018 and June 2019. Patient and disease characteristics are summarized in Fig. 1b, with individual disease characteristics listed in Supplemental Table 1, and three withdrawals prior to initiation of treatment outlined in Supplemental Table 3 as well as Fig. 2. Data collection and analysis was locked as of October 05, 2020; median follow-up was 12.2 months (range 0.33–24.3 months). Median progression-free survival was 4.1 months (range 1.4–12.2 months). Median overall survival was 10.0 months (range 0.3–19.8 months).

Differences in gut microbiota composition between healthy controls and lung cancer patients

Comparisons between LC and HC were restricted to fecal analysis as HC patients did not submit nasal or buccal samples. At the phylum level, LC samples were observed to exhibit lower relative abundances of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, but higher relative abundance of Actinobacteria and Verrucomicrobia. α-diversity (observed OTU) was found to be significantly lower in LC compared to HC samples (p = 9.36 × 10− 04) (Fig. 3a). At the genus level, notable differences were identified between HC and LC patients via PLS-DA as well as heatmap clustering (Fig. 3b). In univariate analysis, a number of taxa showed enrichment or depletion in the LC group compared to HC group: as an example, LC patients exhibited enriched baseline relative abundances of Eggerthella (p = 6.78 × 10− 07, FDR = 2.41 × 10− 05) and decreased Lachnospira (p = 2.00 × 10− 04, FDR = 1.58 × 10− 03). Please see Supplemental Table 4 for full list of bacteria with p and false discovery rate (FDR) values. As expected, β-diversity analysis using Bray-Curtis indices showed the gut microbiome was distinct from nasal and buccal samples (Fig. 3c).

Baseline microbiome composition. Bar and heatmap plots comparing baseline gut, nasal and buccal microbiomes in LC compared to HC. (a) Left: Bar graph showing relative ratios of phyla constitution in LC and HC samples. Right: Box plot showing a statistically significant decrease in α-diversity when comparing LC to HC patients (p = 9.36 × 10− 04). (b) Left: 2-dimensional PLS-DA graph identifying notable differences in genus expression when comparing LC vs HC samples. Right: Heatmap showing genus level expression in LC patients (upper half) compared with HC (lower half). There is a notable difference at the genus level. (c) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) comparing the beta-diversity of buccal, nasal and gut microbiome in LC patients

Response to immunotherapy

Due to limited sample size, only patients receiving combined chemo-immunotherapy were used to determine the effect of microbiome on ICI response. Baseline nasal, buccal and fecal samples from 13 evaluable patients were included for analysis. Despite a consistent trend of higher baseline α-diversity among responders across all microbiome sites (Supplemental Figure 1), no statistically significant difference was observed.

Nasal microbiome analysis identified statistically significant higher relative abundance of Finegoldia (of phylum Firmicutes), p and FDR < 0.05 (p = 5.21 × 10− 04, FDR = 0.018), in patients who enjoyed clinical response to chemoimmunotherapy (Fig. 4a). Anaerococcus, another bacteria of phylum Firmicutes, was significantly higher in responders (p = 2.93 × 10− 04, data not shown). In buccal samples, relative abundance of Megasphaera (phylum Firmicutes) was higher in responders (p = 8.6 × 10− 03), while Actinobacillus (phylum Proteobacteria) was lower (p = 9.7 × 10− 03) (Fig. 4b). In fecal samples, relative abundance of Clostridiales (phylum Firmicutes) was higher in responders (p = 0.017875) whereas Rikenellaceae (phylum Bacteroidetes) was lower (p = 0.016013) (Fig. 4c). In all three microbiome sites, Firmicutes bacteria were enriched in responders.

Response to immunotherapy. Microbiome changes notable in responders to ICI. Normalized data is presented in log-adjusted relative abundances. Left panels show PLS-DA graphs from nasal, buccal and gut sites all showing a microbiome separation when comparing ICI responders vs nonresponders. (a) Taxonomic profiling of nasal samples identified notable enrichment in Finegoldia, of phylum Firmicutes, in responders to ICI (p = 0.0005). (b) Buccal analysis of ICI responders show enrichment in Megasphaera of phylum Firmicutes (p = 8.6 × 10− 03) and decrease in Actinobacillus of phylum Proteobacteria (p = 9.7 × 10− 03). (c) In the fecal samples of ICI responders, Clostridiales was enriched (phylum Firmicutes, p = 0.017875) and Rikenellaceae decreased (phylum Bacteroidetes, p = 0.016013)

Adverse effects

13 patients who experienced treatment related adverse effects provided fecal, buccal and nasal samples for analysis of irAEs (Supplemental Table 2), along with 11 patients who did not develop irAEs. Taxonomic analysis identified multiple differences between microbiota of LC patients with and without adverse effects. At baseline, patients who experienced irAEs had a distinctly different fecal microbiome makeup compared to LC patients with fewer toxicities. Using stringent criteria, requiring p and FDR < 0.05 regardless of different grouping methods of AE severity, enrichment of Bifidobacterium (phylum Actinobacteria) and Desulfovibrio (phylum Proteobacteria) were significantly associated with lower incidence of irAEs. This observation was consistent irrespective of irAE severity grouping - i.e., CTCAE grade 0 vs 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 (Desulfovibrio p = 0.0002, Bifidobacterium p = 0.001), grade 0 + 1 vs grade 2 + 3 + 4 (Desulfovibrio p = 0.0077, Bifidobacterium p = 0.0004), or 0 vs 1 + 2 vs 3 + 4 (Desulfovibrio p = 0.0006, Bifidobacterium p = 0.001) (Fig. 5). Under the same stringent criteria, buccal and nasal samples did not identify clear associations between the microbiome and irAEs, though differences in composition were observed using various grouping methods (Supplemental Figure 2). Increasing the sample size by including patients who provided only nasal and buccal but not stool specimens also did not identify additional significant bacteria, irrespective of grouping (Supplemental Figure 3).

Toxicity analysis. (a) PLS-DA analysis showing significant microbiome differences between LC patients who experienced toxicities and those who did not using different grouping methods of irAE severities, e.g. grade 0 vs. grade 1 + 2 + 3 + 4; grade 0 + 1 vs. grade 2 + 3 + 4; and grade 0 vs. 1 + 2 vs. 3 + 4. (b) Normalized abundances of Bifidobacterium (phylum Actinobacteria) and Desulfovibrio (phylum Proteobacteria) showed enrichment in both bacteria in patients who developed less irAEs. All differences were statistically significant irrespective of categorization of AE severity

Longitudinal changes in microbiome in relation to toxicity

For longitudinal toxicity analysis, 11 patients submitted 2 sets of fecal samples; 3 patients submitted 3 sets. 13 patients submitted 2 sets of nasal and buccal samples; 5 patients submitted 3 sets of nasal and buccal samples. See Supplemental Table 2 for individual reasons for harvest of subsequent sample sets.

For the 8 and 10 patients who submitted two sets of stool and nasal/buccal swabs for irAEs respectively, we found no statistically different changes in α-diversity, though a trend toward reduction in α-diversity in the gut microbiome at onset of toxicity was observed (Supplemental Figure 4). In the 5 patients who provided all 3 sets of microbiomes, a consistent trend toward either slowed or reversed decrease in α-diversity with resolution of irAEs was observed (Fig. 6a), though complete recovery was not exhibited in this cohort.

Longitudinal changes in microbiome with development and resolution of toxicities. (a) Analysis identified five patients who had submitted multiple samples during development and resolution of irAE. JZLC-24 and JZLC-6 did not have stool samples available for analysis but did submit all three sets of nasal and buccal samples. On the x-axis, sample collections are listed: V1, prior to initiation of immunotherapy; V2; at onset of toxicity, and V3, at resolution of irAE. The y-axis denotes the logarithmic (base 10) relative change in α -diversity compared to the previous visit, trended by the line plots, overlaid. Across nearly all sets of microbiome samples, a drop in microbiome α-diversity is observed at onset of irAE. At resolution of irAE to grade 1 severity or better, a third set of samples exhibit a trend toward either slowed rate of decrease in α-diversity or a reversal altogether toward baseline. (b) A consistent trend in increase of Staphylococcus at onset of toxicity and decrease with resolution of toxicity was also observed in the nasal samples (left), with a similar trend in buccal samples (right). (c) Megasphaera, a bacterium belonging to Firmicutes, was previously identified as being enriched in responders to immunotherapy. Here, it is also shown to decrease in buccal samples of patients who developed irAEs, then increasing in abundance with resolution of toxicity

Individual notable changes in the nasal and buccal microbiomes are included in Fig. 6b. Though none reached statistical significance, consistent increases in the relative abundance of Staphylococcus in nasal microbiome at onset of toxicities and concomitant decreases with resolution of toxicities were detected. In addition, the relative abundance of Megasphaera decreased in buccal samples with onset of irAE and increase with resolution of toxicities (Fig. 6c).

Discussion

In our cohort, LC patients were observed to have at baseline significantly decreased α-diversity in the gut microbiome. Decreased α-diversity is suggestive of a certain degree of dysbiosis, reminiscent of previous studies linking gut dysbiosis to carcinogenesis partly via leakage of microbial products that negatively affect the immune system [30]. Decreased α-diversity has been previously directly correlated with an active disease state [14, 31]. We had reported in earlier analyses an inversion in the ratio correlating Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes when comparing LC to HC samples [32]. This inversion was not upheld with increased sample size: when we presented our interim findings in 2019, we had accrued 9 LC patients to compare to 32 HC samples [33]. However, our sample size for comparison in this publication includes 28 LC patients, and our findings are concordant with another study that identified a relative decrease in Firmicutes abundance with simultaneous increased enrichment of Bacteroidetes in LC patients [34]. This could be due to improved elimination of confounders with increased sample size. As seen in Supplemental Table 1, we performed a medicine reconciliation with patients prior to undergoing immunotherapy +/− chemotherapy and identified which of them had been taking antibiotics, probiotics or proton pump inhibitor therapies, as these have been shown to at least temporarily influence microbiome composition. Taking our small sample size into account, we were unable to identify any statistically meaningful signals attributing these variables to our study outcomes. As a medication reconciliation was a standard component of our enrollment process, we will continue to evaluate the potential value of these variables with future trials.

Multiple bacteria have been associated with potentiation of immunotherapy, including Akkermansia, Faecalibacterium, and Bifidobacterium [35]. Prior studies established that increased diversity in the microbiome is associated with response to immunotherapy in melanoma patients [22, 36, 37]. This correlation appears to have an amplifying effect on treatment efficacy: in a 2019 study, survival also seemed to increase with increasing α-diversity [37]. Though our study could not confirm those findings, likely due to underpowered sample size, this trend was observed.

Buccal and nasal samples yielded an increase in relative abundance of Megasphaera and Finegoldia, respectively, of phylum Firmicutes, in responders to combined chemoimmunotherapy; and increased Actinobacillus, a Proteobacterium, in nonresponders. In all three collection sites, Firmicutes bacteria (Finegoldia in nasal, Megasphaera in buccal, and Clostridiales in gut) were enriched in responders. Our recent systematic review of clinical studies suggests enrichment of Firmicutes in the gut microbiome correlates significantly with increasing chemoimmunotherapy response across various solid tumors [38]. Firmicutes bacteria are prominent producers of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which have been linked to major immunoregulatory effects in the gut [30]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated the potential contribution of various SCFAs in patient immunity, particularly butyrate, which has been theorized at high concentrations to foster anti-tumor effects via activation of effector CD4 and CD8 responses [39,40,41]. The implications of a nasal or buccal sample being able to correlate with clinical outcomes in concordance with fecal samples would lend credence to the concept of immune systemic crosstalk, as well as improve the feasibility of utilizing the microbiome for predictive purposes. In our study, patients had a far easier time providing nasal and buccal swabs than fecal samples – compliance rate of nasal/buccal sample return was 97% - only one sample had been excluded due to mislabeling.

The significance of reduced relative abundance of Actinobacillus (phylum Proteobacteria) in the gut microbiome of chemoimmunotherapy responders is less clear. Increased Proteobacteria has been previously associated with dysbiosis [42, 43], and enterocolic inflammation possibly through local induction of intestinal Th17 cell responses [44]. Helicobacter pylori, a prominent Proteobacterium, has been found to utilize multiple mechanisms to incite local inflammation while simultaneously evading its own destruction via interleukin-33, which decreases interferon-γ production [45,46,47]. A similar mechanism may exist for Actinobacillus.

Our study made a novel association between decreased relative abundance of Rikenellaceae (phylum Bacteroidetes) and chemoimmunotherapy response. Current understanding of Bacteroidetes’ function in response to ICI is mixed; Bacteroidetes have been demonstrated to increase regulatory T-cell differentiation as well as increase levels of IL-10 via use of Polysaccharide A, leading to upregulation of CTLA-4 expression [21]. It is important to note that certain species of Bacteroidetes, such as B. thetaiotomicron, and B. fragilis have been paradoxically shown to improve tumor control with CTLA-4 therapy [18]. ICI response with these specific species was theorized to be due to release of outer membrane vesicles containing enzymes that degrade gut mucin and improve presentation to dendritic cells, thus stimulating a stronger immune response [48]. It is possible this ability to potentiate immunotherapy is species-specific, not phylum-specific – this is indeed supported by findings from multiple studies across various solid tumors [49], and that the overall function of Bacteroidetes, specifically Rikenellaceae, could be immunosuppressive.

Our study is likely among the first to directly associate specific bacterial genera with irAE development. Particularly notable is association of Bifidobacterium enrichment with decreased irAEs. Bifidobacterium is a well-characterized probiotic and has been previously associated with alleviation of immunologic colitis caused by anti-CTLA-4 therapy: this effect is hypothesized to involve modulation of existing regulatory T-cells without major change on influx or distribution [50]. Bifidobacterium was found to reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17 and TNF, both of which play a critical role in development of irAEs [5, 49, 51, 52]. Interestingly, we also found that Desulfovibrio (phylum Proteobacteria) enrichment was significantly associated with decreased irAEs. Existing literature regarding its immunomodulatory behavior is scarce, and functional intraspecies differences have been identified [53]. Between strains, the rate of sulfate metabolism from SCFAs and thus possible consequent generation of enterotoxic hydrogen sulfides can vary dramatically [54, 55]. Whether the strain we identified in our study specifically dampens inflammatory response to ICI will require more focused analysis. In addition to development of lung cancer and poor response to ICI, Proteobacteria has been correlated with lower incidence of irAEs [56, 57]. It is unclear why our gut microbiome toxicity findings were not mirrored in nasal or buccal sets as they were with response data. We speculate irAEs are primarily a systemic response to which the gut microbiome wields significant influence given a much larger commensal bacteria mass, whereas ICI response is primarily determined by the tumor immune microenvironment and hence is likely modulated by local (e.g. nasal and buccal) microbiota as well.

Longitudinally collected samples appeared to show consistent loss of α-diversity in buccal, nasal and gut microbiomes with onset of irAEs, with a trend toward either decreased rate of diversity loss or outright improvement at resolution of toxicity. The lack of statistical significance here may simply be a matter of sample size. It is possible that patients who experience irAEs eventually recover baseline microbiome composition with longer follow-up: future studies designed to obtain samples far after resolution may confirm recovery of baseline microbiome diversity. It also remains unclear whether increased biodiversity in HCs is reflective of bio-reductive activity by malignancy or a baseline trait of the host in general, which could also reflect better overall health and performance status and thus prolong survival [58].

We identified two specific phenomena with longitudinal sampling. First, we noted an increase in Staphylococcus relative abundance in nasal samples at onset of irAE. Staphylococcus has been implicated as an active regulator of competitive bacterial growth, and was also significantly upregulated in the nares of patients with autoimmune disease [59, 60]; further testing could clarify its role as a surrogate marker of irAE changes. The relative abundance of Megasphaera was also found to decrease and increase, respectively, with onset and resolution of toxicities in buccal samples. Firmicutes genera, enriched in the baseline gut microbiome of LC patients, has been previously associated with development of CTLA-4 mediated colitis [21, 61]. Firmicutes-produced SCFAs have been demonstrated to activate multiple types of G-protein coupled receptors, stimulating either proinflammatory (via MAP kinase) or anti-inflammatory (via β-arrestin 2) responses [14]. Thus, Megasphaera’s decrease with onset of toxicity may be indicative of this Firmicutes bacteria instigating its own immunologic reaction. Further investigation is needed to confirm.

The patient population of our pilot study contained both NSCLC and SCLC patients. Four SCLC patients were included in different stages of analysis, with three patients who underwent first-line chemoimmunotherapy and one patient with second-line ICI monotherapy; the latter patient progressed on second-line therapy and the three treatment-naïve patients exhibited response. Repeat analysis with removal of SCLC patients slightly decreased significance of but did not fundamentally change our findings. Considering NSCLC and SCLC are cancers of the same organ and carry overlapping environmental risk factors, such as smoking exposure, and that our intent is to identify which members of the respiratory microbiome may be associated with ICI response, we reported results from analysis performed on the aggregate cohort. Given that our findings are similar to those found in microbiome studies of melanoma [19, 22, 48, 62] and renal cell carcinoma [20] patients, it is also reasonable to consider that the microbiome compositions portending response to immunotherapy may also be disease agnostic.

Our study has several limitations that will benefit principally from a larger patient pool. One patient was lost to follow-up shortly after achieving a partial response. Due to follow-up difficulties, several patients were unable to obtain second and third sets of samples for toxicity evaluation. The trends we identified with respect to longitudinal microbiome changes with AEs were drawn from a subset of 5 of 34 possible patients, trends which, albeit interesting, require further validation. Some of the treatment arms, such as LC patients treated with ICI monotherapy, could not be investigated due to small sample size. Based on our current cohort and effect size calculations, we were able to detect 2.16- and 1.23-fold changes in taxa abundance for the ICI response and irAE analyses, respectively [63]. Given that all patients included in ICI response analysis had been treated with chemoimmunotherapy, it is possible that chemotherapy could also have contributed to response rates as well as microbiome alteration. We are currently accruing patients to a subsequent study that will specifically delineate patients treated only with immunotherapy, or are immunotherapy-naïve, for evaluation (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04636775, NCT04680377). HC samples used in this analysis also differed from the patient population – controls were relatively younger, though from the same geographic region, and were only able to provide stool samples for comparison. We felt disclosing the LC/HC fecal sample comparison valuable for two specific reasons: first, it is important to confirm that in concordance with other studies the patient population and healthy population have markedly different microbiota at baseline, and second, we feel it important to have two baselines for comparison – a healthy control and a lung cancer baseline control – given that over the course of therapy, many external factors, including chemotherapy, may further perturb that balance. The potential value of such a corroboration, as identified in prior studies [15, 64,65,66], is that changes in the microbiome may be associated with carcinogenesis as well as with poorer responses to therapy.

Our initial exploratory study may help answer which patients may be at highest risk of developing life-threatening irAEs with use of ICI. More importantly, we hope to identify associations between microbiome constitution and increased immunotherapy efficacy. The potentiation of immunotherapy carries broad implications, including in cancers for which immunotherapy is not currently indicated. A larger cohort to account for confounding factors will further elaborate this: a study focusing on immunotherapy naïve advanced/metastatic NSCLC receiving single agent anti-PD-1/L1 has opened at the University of Kansas Medical Center (due to PI Dr. Jun Zhang’s relocation, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04636775). In addition, a separate trial studying the role of the microbiome in predicting toxicity of the anti-PD-L1 agent durvalumab following concurrent chemoradiation in locally advanced NSCLC patients is open to accrual (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04680377; PI Dr. Jun Zhang).

Our research is the first to comprehensively compare oral, nasal and fecal samples among LC patients and report correlations between them with respect to immunotherapy response. It is also notable for being the first to associate Bifidobacterium and Desulfovibrio with decreased development of irAEs, and further, for being the first to attempt a longitudinal study to evaluate dynamic microbiome changes from various body sites – all these findings will benefit from further investigation in continued preclinical and clinical studies.

Conclusions

Our study identified multiple promising associations between microbiome alterations and outcomes following ICI therapy in LC patients. Though development of irAEs have been classically associated with treatment response, our findings show that shifts in abundance of specific species may affect only one of these phenomena, potentially decoupling them. Lastly, our study suggests shared correlations between treatment outcomes and disparate microbiome sites in LC patients, which could hold promising predictive value. Our findings warrant further validation with a larger cohort and mechanistic dissection using preclinical models.

Availability of data and materials

Raw data used for analysis has been uploaded to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BioSample database under BioProject ID PRJNA687361, currently pending review and publication. 68 to 93% of input reads remained following denoising with DADA2.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- CR:

-

Complete response

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- ICI:

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitor

- irAE:

-

Immune-related adverse event

- HC:

-

Healthy control

- LC:

-

Lung cancer

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- OTU:

-

Operational taxonomic unit

- PCoA:

-

Principal coordinate analysis

- PLS-DA:

-

Partial least squares discriminant analysis

- PR:

-

Partial response

- SCFA:

-

Short chain fatty acid

- SCLC:

-

Small cell lung cancer

References

Swami U, Zakharia Y, Zhang J. Understanding microbiome Effect on immune checkpoint inhibition in lung Cancer: placing the puzzle pieces together. J Immunother. 2018;41(8):359–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/CJI.0000000000000232.

Strouse C, Mangalam A, Zhang J. Bugs in the system: bringing the human microbiome to bear in cancer immunotherapy. Gut Microbes. 2019;10(2):109–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2018.1511665.

Temraz S, Nassar F, Nasr R, Charafeddine M, Mukherji D, Shamseddine A. Gut Microbiome: A Promising Biomarker for Immunotherapy in Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(17). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20174155.

Liong MT. Roles of probiotics and prebiotics in colon cancer prevention: postulated mechanisms and in-vivo evidence. Int J Mol Sci. May 2008;9(5):854–63. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms9050854.

Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014;157(1):121–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011.

Zhang H, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Hernandez-Diaz S. Antibiotic use and the risk of lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. Jun 2008;17(6):1308–15. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2817.

Sacksteder MR. Occurrence of spontaneous tumors in the germfree F344 rat. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;57(6):1371–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/57.6.1371.

Laqueur G, Matsumoto H, Yamamoto R. Comparison of the carcinogenicity of Methylazoxymethanol-B-D-glucosiduronic acid in conventional and germfree Sprague-Dawley rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981;67(5):1053–5.

Maddi A, Sabharwal A, Violante T, et al. The microbiome and lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(1):280–91. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2018.12.88.

Zhang D, Li S, Wang N, Tan HY, Zhang Z, Feng Y. The cross-talk between gut microbiota and lungs in common lung diseases. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:301. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00301.

Keely S, Talley NJ, Hansbro PM. Pulmonary-intestinal cross-talk in mucosal inflammatory disease. Mucosal Immunol. Jan 2012;5(1):7–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2011.55.

Abrahamsson TR, Jakobsson HE, Andersson AF, Bjorksten B, Engstrand L, Jenmalm MC. Low gut microbiota diversity in early infancy precedes asthma at school age. Clin Exp Allergy. Jun 2014;44(6):842–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.12253.

Belkaid Y, Harrison OJ. Homeostatic Immunity and the Microbiota. Immunity. 2017;46(4):562–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.008.

Dang AT, Marsland BJ. Microbes, metabolites, and the gut-lung axis. Mucosal Immunol. Jul 2019;12(4):843–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41385-019-0160-6.

Jin C, Lagoudas GK, Zhao C, et al. Commensal Microbiota Promote Lung Cancer Development via gammadelta T Cells. Cell. 2019;176(5):998–1013 e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.040.

Paulos CM, Wrzesinski C, Kaiser A, et al. Microbial translocation augments the function of adoptively transferred self/tumor-specific CD8+ T cells via TLR4 signaling. J Clin Invest. Aug 2007;117(8):2197–204. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI32205.

Pitt JM, Vetizou M, Waldschmitt N, et al. Fine-Tuning Cancer Immunotherapy: Optimizing the Gut Microbiome. Cancer Res. 2016;76(16):4602–7. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0448.

Vetizou M, Pitt JM, Daillere R, et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science. 2015;350(6264):1079–84. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad1329.

Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science. 2015;350(6264):1084–9. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4255.

Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359(6371):91–7. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan3706.

Chaput N, Lepage P, Coutzac C, et al. Baseline gut microbiota predicts clinical response and colitis in metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(6):1368–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx108.

Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L, et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359(6371):97–103. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan4236.

Shahi SK, Zarei K, Guseva NV, Mangalam AK. Microbiota Analysis Using Two-step PCR and Next-generation 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing. J Vis Exp. 2019;(152). https://doi.org/10.3791/59980.

Yilmaz P, Parfrey LW, Yarza P, Gerken J, Pruesse E, Quast C, et al. The SILVA and “all-species living tree project (LTP)” taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(D1):D643–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt1209.

Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJ, Holmes SP. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. Jul 2016;13(7):581–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3869.

Chong J, Liu P, Zhou G, Xia J. Using MicrobiomeAnalyst for comprehensive statistical, functional, and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nat Protocol. 2020;15(3):799–821. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-019-0264-1.

Arndt D, Xia J, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Guo AC, Cruz JA, et al. METAGENassist: a comprehensive web server for comparative metagenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(W1):W88–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks497.

Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1709937.

Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, et al. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32222-6.

Biragyn A, Ferrucci L. Gut dysbiosis: a potential link between increased cancer risk in ageing and inflammaging. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(6):e295–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30095-0.

Chen J, Chia N, Kalari KR, et al. Multiple sclerosis patients have a distinct gut microbiota compared to healthy controls. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28484. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28484.

Chau JJ, Yadav M, Furqan M, et al. Analysis of patient microbiome and its correlation to immunotherapy response and toxicity in lung cancer. Abstract. In: World Conference on Lung Cancer. Barcelona: International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer; 2019 September 7–10 2019:Abstract P2.04–18.

Zhang J. Analysis of patient microbiome and its correlation to immunotherapy response and toxicity in lung Cancer. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer; 2019:

Zhang WQ, Zhao SK, Luo JW, Dong XP, Hao YT, Li H, et al. Alterations of fecal bacterial communities in patients with lung cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2018;10(10):3171–85.

Wu X, Zhang T, Chen X, Ji G, Zhang F. Microbiota transplantation: targeting cancer treatment. Cancer Lett. Jun 28 2019;452:144–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2019.03.010.

Gong J, Chehrazi-Raffle A, Placencio-Hickok V, Guan M, Hendifar A, Salgia R. The gut microbiome and response to immune checkpoint inhibitors: preclinical and clinical strategies. Clin Transl Med. 2019;8(1):9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40169-019-0225-x.

Jin Y, Dong H, Xia L, Yang Y, Zhu Y, Shen Y, et al. The diversity of gut microbiome is associated with favorable responses to anti-programmed death 1 immunotherapy in Chinese patients with NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. Aug 2019;14(8):1378–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2019.04.007.

Huang C, Li M, Liu B, et al. Relating Gut Microbiome and Its Modulating Factors to Immunotherapy in Solid Tumors: A Systematic Review. Systematic Review. Front Oncol. 2021;11(760). https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.642110.

Luu M, Weigand K, Wedi F, et al. Regulation of the effector function of CD8(+) T cells by gut microbiota-derived metabolite butyrate. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14430. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32860-x.

Trompette A, Gollwitzer ES, Pattaroni C, et al. Dietary Fiber Confers Protection against Flu by Shaping Ly6c(−) Patrolling Monocyte Hematopoiesis and CD8(+) T Cell Metabolism. Immunity. 2018;48(5):992–1005 e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.022.

Park J, Kim M, Kang SG, Jannasch AH, Cooper B, Patterson J, et al. Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory T cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mTOR-S6K pathway. Mucosal Immunol. Jan 2015;8(1):80–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2014.44.

Byndloss MX, Olsan EE, Rivera-Chavez F, et al. Microbiota-activated PPAR-gamma signaling inhibits dysbiotic Enterobacteriaceae expansion. Science. 2017;357(6351):570–5. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aam9949.

Litvak Y, Byndloss MX, Baumler AJ. Colonocyte metabolism shapes the gut microbiota. Science. 2018;362(6418). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat9076.

Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Ando M, et al. Th17 Cell Induction by Adhesion of Microbes to Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Cell. 2015;163(2):367–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.058.

Suarez G, Romero-Gallo J, Piazuelo MB, et al. Nod1 Imprints Inflammatory and Carcinogenic Responses toward the Gastric Pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Cancer Res. 2019;79(7):1600–11. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2651.

Tran LS, Tran D, De Paoli A, et al. NOD1 is required for helicobacter pylori induction of IL-33 responses in gastric epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2018;20(5):e12826. https://doi.org/10.1111/cmi.12826.

Lehours P, Ferrero RL. Review: Helicobacter: Inflammation, immunology, and vaccines. Helicobacter. 2019;24(Suppl 1):e12644. https://doi.org/10.1111/hel.12644.

Frankel AE, Coughlin LA, Kim J, Froehlich TW, Xie Y, Frenkel EP, et al. Metagenomic shotgun sequencing and unbiased Metabolomic profiling identify specific human gut microbiota and metabolites associated with immune checkpoint therapy efficacy in melanoma patients. Neoplasia. Oct 2017;19(10):848–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neo.2017.08.004.

Huang C, Li M, Liu B, et al. Relating Gut Microbiome and Its Modulating Factors to Immunotherapy in Solid Tumors: A Systematic Review. Research Square. 2020. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-73124/v1.

Wang F, Yin Q, Chen L, Davis MM. Bifidobacterium can mitigate intestinal immunopathology in the context of CTLA-4 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(1):157–61. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1712901115.

McGeachy MJ, Cua DJ, Gaffen SL. The IL-17 Family of Cytokines in Health and Disease. Immunity. 2019;50(4):892–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.021.

Schirmer M, Smeekens SP, Vlamakis H, et al. Linking the Human Gut Microbiome to Inflammatory Cytokine Production Capacity. Cell. 2016;167(4):1125–1136 e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.020.

Warren YA, Citron DM, Merriam CV, Goldstein EJ. Biochemical differentiation and comparison of Desulfovibrio species and other phenotypically similar genera. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(8):4041–5. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.43.8.4041-4045.2005.

Rowan F, Docherty NG, Murphy M, Murphy B, Calvin Coffey J, O'Connell PR. Desulfovibrio bacterial species are increased in ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon rectum. 2010;53(11):1530–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181f1e620.

Dzierzewicz Z, Cwalina B, Kuśmierz D, Kwapisz I. Differences between Desulfovibrio desulfuricans intestinal strains with respect to their ability of sulphasalazine biotransformation. Acta Pol Pharm. 2000;57:124–6.

Wilson ID, Nicholson JK. Gut microbiome interactions with drug metabolism, efficacy, and toxicity. Transl Res. Jan 2017;179:204–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2016.08.002.

Greathouse KL, White JR, Vargas AJ, et al. Interaction between the microbiome and TP53 in human lung cancer. Genome Biol. 2018;19(1):123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-018-1501-6.

Hekmatshoar Y, Rahbar Saadat Y, Hosseiniyan Khatibi SM, et al. The impact of tumor and gut microbiotas on cancer therapy: Beneficial or detrimental? Life Sci. 2019;233:116680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116680.

Otto M. Staphylococci in the human microbiome: the role of host and interbacterial interactions. Curr Opin Microbiol. Feb 2020;53:71–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2020.03.003.

Ceccarelli F, Perricone C, Olivieri G, et al. Staphylococcus aureus Nasal Carriage and Autoimmune Diseases: From Pathogenic Mechanisms to Disease Susceptibility and Phenotype. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(22). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20225624.

Helmink BA, Khan MAW, Hermann A, Gopalakrishnan V, Wargo JA. The microbiome, cancer, and cancer therapy. Nat Med. Mar 2019;25(3):377–88. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0377-7.

Matson V, Fessler J, Bao R, Chongsuwat T, Zha Y, Alegre ML, et al. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti–PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359(6371):104–8. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao3290.

Stangroom J. Effect Size Calculator for T-Test. Jeremy Stangroom. May 15, 2021, 2021. Accessed May 13, 2021, 2021. https://www.socscistatistics.com/effectsize/default3.aspx

Bullman S. Analysis of Fusobacterium persistence and antibiotic response in colorectal cancer. Science. 2017;358(6369):1443–8. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal5240.

Yu T, Guo F, Yu Y, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Chemoresistance to Colorectal Cancer by Modulating Autophagy. Cell. 2017;170(3):548–563 e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.008.

Zorron Cheng Tao Pu L, Yamamoto K, Honda T, Nakamura M, Yamamura T, Hattori S, et al. Microbiota profile is different for early and invasive colorectal cancer and is consistent throughout the colon. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(3):433–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.14868.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank Francesca Nugent, Nicole Cady, Kasey Lockett and Ashley McCarthy for consenting patients, delivering specimens and maintaining the database for patient accrual.

Funding

This study is supported by various research funds including the Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center Enhancement Grant (JZ); The University of Kansas Start-Up (JZ); The “Play with a Pro” Lung Cancer Research Fund (JZ); the gift from Margaret Heppelmann and Michael Wace (AM); NIH/NCI P30CA086862 Cancer Center Support Grant (GW) for supporting the Biospecimen Procurement and Molecular Epidemiology Resource Core (CC); and the National Science Foundation under Grant No. DBI-1943291 (CZ). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JZ conceived, designed and developed this study. JC drafted the initial manuscript with specific oversight and guidance from JZ. BL drafted the microbiome assessments section in Methods with revisions by CZ, SL, AM, GW, and MY. MY, KNM, EE, CC1, CC2, SS, AG, QD and AM were responsible for data collection and specimen management and processing. JC, MF, TAH, and JZ maintained clinical correlations between microbiome and patient outcomes. BL, AG, CZ, AM and JZ performed data analysis. All authors (JC, MY, BL, SS, AG, EE, KNM, TAH, MF, CC1, CC2, GW, QD, AM, SL, CZ, JZ) reviewed, revised and approved the final draft for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This trial protocol was approved by the University of Iowa institutional review board. All investigators collected data. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to enrollment and participation in this study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of their clinical details and/or clinical.

images was obtained from the patient/parent/guardian/ relative of the patient. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chau, J., Yadav, M., Liu, B. et al. Prospective correlation between the patient microbiome with response to and development of immune-mediated adverse effects to immunotherapy in lung cancer. BMC Cancer 21, 808 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08530-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08530-z