Abstract

Background

The aim of our study was to investigate whether an inflammation-based prognostic score, the prognostic nutritional index (PNI), was associated with clinical characteristics and prognosis in patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSC).

Methods

We retrospectively investigated 875 patients who underwent primary staging or debulking surgery for HGSC between April 2005 and June 2013 at our institution. None of these patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Preoperative PNI was calculated as serum albumin (g/L) + 0.005 × lymphocyte count (per mm3). The optimal PNI cutoff value for overall survival (OS) was identified using the online tool “Cutoff Finder”. Clinical characteristics and PNI were compared with chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. The impact of PNI on OS was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method and Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

The median (range) PNI was 46.2 (29.2–67.7). The 45.45 cutoff value discriminated patients into the high-PNI and low-PNI groups. A low preoperative PNI was associated with an advanced FIGO stage, increased CA125 level, more extensive ascites, residual disease and platinum resistance. For univariate analyses, a high PNI was associated with increased OS (p < 0.001). In multivariate analyses, the PNI remained an independent predictor of OS as a continuous variable (p = 0.021) but not as dichotomized groups (p = 0.346).

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that the PNI could be a predictive and prognostic parameter for HGSC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Ovarian cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed and lethal diseases among women worldwide [1]. Although most patients underwent primary surgery and platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy, half of the patients will relapse within 16 months [2].

Approximately two-thirds of all patients are of advanced stage at diagnosis, with widespread intra-abdominal disease [1, 2]. Patients are at high risk of malnutrition due to cachexia and ascites. Additionally, systemic inflammation also plays an important role during cancer initiation and progression [3]. Accordingly, the identification of relative biomarkers to predict treatment outcomes and prognosis are urgently required.

The prognostic nutritional index (PNI), which can be calculated by the serum albumin concentration and the peripheral blood lymphocyte count, could quantify both the nutritional and immunological status of the body [3, 4]. Currently, the predictive and prognostic role of the PNI has been uncovered in various malignancies [4,5,6,7,8,9]. However, there are limited data showing the application of the PNI in ovarian cancer [10, 11].

In addition, ovarian cancer is a group of heterogeneous tumors based on distinctive morphological and molecular genetic features [12]. Previous studies have combined these disease subtypes but failed to individually evaluate the clinical and prognostic value of the PNI according to the histologic type.

Since the vast majority of ovarian cancers are high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSC), the purpose of our study was to investigate the clinical and prognostic significance of preoperative PNI in HGSC patients.

Methods

Clinical data

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Committee at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center. All participants provided written informed consent.

We retrospectively investigated 875 patients who underwent primary staging or debulking surgery for HGSC between April 2005 and June 2013 at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center. The pathological diagnoses were reviewed according to WHO criteria by two experienced gynecologic pathologists.

The inclusion criteria and clinical data collection were consistent with our previous studies [13, 14]. Besides, we also collected BMI, albumin and lymphocyte count data for this study.

Preoperative blood samples from the patient were drawn by antecubital venipuncture within 1 week prior to the operation. The PNI was calculated as serum albumin (g/L) + 0.005 × lymphocyte count (per mm3). R0 was defined as the absence of macroscopic residual disease (RD) after surgery. According to the response to platinum-based chemotherapy, patients were clarified as platinum sensitive and platinum resistant [13, 14]. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time interval from the date of the primary surgery to the date of death or the last follow-up (December 31st, 2016).

Statistical analyses

SPSS software (version 21.0, SPSS, IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Comparisons between categorical variables were performed using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. The optimal cutoff value for the PNI was determined via a web-based system Cutoff Finder by Budczies et al. (http://molpath.charite.de/cutoff) [15]. The OS was analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank tests in the univariate analyses. The Cox regression analysis was used for multivariate analyses. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all reported P values were 2-sided.

Results

Patient characteristics

The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median (range) age of the patients was 56 (30–90) years old. Over 90% of the patients (800/875) had advanced stage (III-IV). After primary surgery, 272 (31.1%) of the patients were debulked to R0 and 603 (68.9%) patients had residual disease. After primary surgery, the majority of patients (849/875, 97.0%) had received platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy, and 568 (66.9%) patients were platinum sensitive.

Cutoff point for determining the PNI

The PNI ranged from 29.2 to 67.7, with a median level of 46.2. Based on the Cutoff Finder tool, a wide range of cutoff points for the PNI was significant with respect to OS (Fig. 1). In addition, the optimal cutoff point of the PNI was 45.45. Then, patients were divided into high PNI (PNI ≥ 45.45, n = 472, 54.5%) and low PNI groups (PNI < 45.45, n = 394, 45.5%).

Correlations between the PNI and clinical characteristics

Correlations of the clinical characteristics with the preoperative PNI are summarized in Table 2. A low preoperative PNI level was associated with an advanced FIGO stage (p < 0.001), an increased CA125 level (p < 0.001) and more extensive ascites (p < 0.001). Patients who presented with a high PNI level tended to have no residual disease (p < 0.001). A greater proportion of the patients in the high PNI group were platinum sensitive compared with those in the low PNI group (76.6% vs 62.8%, p < 0.001). We found that underweight patients and obese patients tended to have low PNI levels compared with the others (p = 0.023).

Prognostic impact of the PNI

The median follow-up time was 41 (1–134) months. A total of 257 (29.4%) patients were still alive at last follow-up, and 457 (52.2%) deaths were documented. The median (95% CI) OS was 55 (49.3–60.7) months.

The known negative influences of an advanced FIGO stage (< 0.001), the presence of residual disease (p < 0.001), and platinum resistance (p < 0.001) for OS were confirmed by univariate analyses.

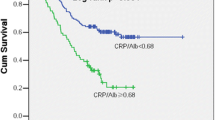

In the univariate analysis, a high PNI was associated with prolonged OS (64.0 (55.8–72.2) vs 44.0 (36.8–51.2) months, p<0.001, Fig. 2). In the multivariate analysis with adjustments for age, FIGO stage, residual disease and platinum sensitivity status, the PNI was also an independent predictor for OS as a continuous variable (HR = 0.980, 95% CI, 0.964–0.997, p = 0.021; Table 3). However, the PNI was not independently associated with OS as dichotomized groups (HR = 0.907, 0.741–1.111, p = 0.346; Table 4).

Discussion

In this large single institutional study with ten-year follow-up, we demonstrated that the preoperative PNI was associated with clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes. A low PNI level was correlated with impaired OS in Chinese patients with HGSC.

The immunological and nutritional condition could undoubtedly influence patient outcomes, and various relative markers have been established [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Among these markers, the PNI could reflect both the nutritional and immunological statuses of the host and has been validated as an indicator for treatment outcomes in various malignancies [4,5,6,7,8,9].

The data on ovarian cancer are quite limited. Miao et al. [10] reported that the PNI could help predict the platinum resistance of ovarian cancer (AUC = 0.688), and in their cohort, the PNI was also an independent prognostic factor for PFS and OS. Zhang et al. [11] further compared several inflammation- and nutrition-related factors and found that the PNI was superior to C-reactive protein/albumin ratio (CAR), modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS), and lymphocyte/monocyte ratio (LMR).

These findings are consistent with previously published data. We observed that low PNI levels were associated with an advanced FIGO stage, an increased CA125 level and more extensive ascites. Thus, higher tumor burden could likely lead to malnutrition and immune suppression, potentially reflected by a low PNI level. Thus, the PNI could reflect tumor burden and was undoubtedly correlated with debulking outcomes for ovarian cancer patients.

In addition, the chemotherapeutic response could be influenced by residual tumor, patient tolerability, and host defense against cancer. Consistent with Miao et al. [10], we propose that a greater proportion of the patients in the high PNI group were platinum sensitive compared with those in the low PNI group. Therefore, the comprehensive nutritional and immune indicator could help predict ovarian cancer patient platinum sensitivity.

Furthermore, both Miao et al. [10] and Zhang et al. [11] reported that the PNI was an independent prognostic factor. However, in the present cohort, the PNI was also an independent predictor for OS as a continuous variable but not as dichotomized groups. The underlying reason was that the definitive normal range of the PNI has not been determined, and the border value to dichotomize the study population into high and low PNI groups is difficult to determine. An epidemiological survey is required for the generation of a normal range.

A notable limitation is that the present study was a retrospective study with potential recall bias. However, the completeness of clinical data, up to 10-year follow-up duration and the large sample size could partly compensate for this limitation. Notwithstanding its limitation, this study was a single institutional retrospective study involving a group of homogeneous patients with the same histology who underwent similar treatment strategies, and the PNI is available in routine blood tests and can be popularized in clinical application.

Conclusion

Our study indicated that preoperative PNI could reflect tumor burden and thus indicate clinical outcomes to a certain extent. This index should be regarded as a predictive and prognostic factor for our HGSC patients.

Abbreviations

- HGSC:

-

High-grade serous ovarian cancer (LGSC)

- OS:

-

Overall survival; RD, Residual disease

- PNI:

-

Prognostic nutritional index

References

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108.

Berek JS, Crum C, Friedlander M. Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;119(Suppl 2):S118–S29.

Buzby GP, Mullen JL, Matthews DC, Hobbs CL, Rosato EF. Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery. Am J Surg. 1980;139(1):160–7.

Onodera T, Goseki N, Kosaki G. Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery of malnourished cancer patients. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1984;85(9):1001–5.

Chan AW, Chan SL, Wong GL, Wong VW, Chong CC, Lai PB, Chan HL, To KF. Prognostic nutritional index (PNI) predicts tumor recurrence of very early/early stage hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(13):4138–48.

Nozoe T, Ninomiya M, Maeda T, Matsukuma A, Nakashima H, Ezaki T. Prognostic nutritional index: a tool to predict the biological aggressiveness of gastric carcinoma. Surg Today. 2010;40(5):440–3.

Sun K, Chen S, Xu J, Li G, He Y. The prognostic significance of the prognostic nutritional index in cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140(9):1537–49.

Kwon WA, Kim S, Kim SH, Joung JY, Seo HK, Lee KH, Chung J. Pretreatment prognostic nutritional index is an independent predictor of survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with targeted therapy. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15(1):100–11.

Ye LL, Oei RW, Kong FF, Du CR, Zhai RP, Ji QH, Hu CS, Ying HM. The prognostic value of preoperative prognostic nutritional index in patients with hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective study. J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):12.

Miao Y, Li S, Yan Q, Li B, Feng Y. Prognostic significance of preoperative prognostic nutritional index in epithelial ovarian Cancer patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Oncol Res Treat. 2016;39(11):712–9.

Zhang W, Ye B, Liang W, Ren Y. Preoperative prognostic nutritional index is a powerful predictor of prognosis in patients with stage III ovarian cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9548.

Kurman RJ, Shih I-M. The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian Cancer: a proposed unifying theory. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(3):433–43.

Feng Z, Wen H, Bi R, Duan Y, Yang W, Wu X. Thrombocytosis and hyperfibrinogenemia are predictive factors of clinical outcomes in high-grade serous ovarian cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:43.

Feng Z, Wen H, Bi R, Ju X, Chen X, Yang W, Wu X. A clinically applicable molecular classification for high-grade serous ovarian cancer based on hormone receptor expression. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25408.

Budczies J, Klauschen F, Sinn BV, Gyorffy B, Schmitt WD, Darb-Esfahani S, Denkert C. Cutoff finder: a comprehensive and straightforward web application enabling rapid biomarker cutoff optimization. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51862.

Asher V, Lee J, Bali A. Preoperative serum albumin is an independent prognostic predictor of survival in ovarian cancer. Med Oncol. 2012;29(3):2005–9.

Yim GW, Eoh KJ, Kim SW, Nam EJ, Kim YT. Malnutrition identified by the nutritional risk index and poor prognosis in advanced epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Nutr Cancer. 2016;68(5):772–9.

Ishizuka M, Nagata H, Takagi K, Iwasaki Y, Shibuya N. Kubota K. Ann Surg Oncol: Clinical Significance of the C-Reactive Protein to Albumin Ratio for Survival After Surgery for Colorectal Cancer; 2015.

Anestis A, Karamouzis MV, Dalagiorgou G, Papavassiliou AG. Is androgen receptor targeting an emerging treatment strategy for triple negative breast cancer? Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41(6):547–53.

Bishara S, Griffin M, Cargill A, Bali A, Gore ME, Kaye SB, Shepherd JH, Van Trappen PO. Pre-treatment white blood cell subtypes as prognostic indicators in ovarian cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;138(1):71–5.

Guthrie GJ, Charles KA, Roxburgh CS, Horgan PG, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: experience in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88(1):218–30.

Feng Z, Wen H, Bi R, Ju X, Chen X, Yang W, Wu X. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictive and prognostic factor for high-grade serous ovarian Cancer. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0156101.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all doctors, nurses, patients, and their family members for their kindness to support our study.

Funding

This work was supported by the leading project of Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (15411962000) for XH Wu. The funding body supervised the application of the fund during the study and would examine the study design, data analysis and article publication.

Availability of data and materials

The institutional ovarian cancer database involves sensitive patient information, which is available upon request. Anyone who is interested in the information should contact docwuxh@hotmail.com or wu.xh@fudan.edu.cn.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZF and HW participated in the study design, carried out the data collection, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. XZJ carried out the data collection and performed the statistical analysis. RB and WTY participated in the pathologic review of all slides. XJC carried out the data collection, reviewed and edited the manuscript. XHW conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Committee at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, Z., Wen, H., Ju, X. et al. The preoperative prognostic nutritional index is a predictive and prognostic factor of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 18, 883 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4732-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4732-8