Abstract

Background

Estimates of cancer prevalence are widely based on limited duration, often including patients living after a cancer diagnosis made in the previous 5 years and less frequently on complete prevalence (i.e., including all patients regardless of the time elapsed since diagnosis). This study aims to provide estimates of complete cancer prevalence in Italy by sex, age, and time since diagnosis for all cancers combined, and for selected cancer types. Projections were made up to 2020, overall and by time since diagnosis.

Methods

Data were from 27 Italian population-based cancer registries, covering 32% of the Italian population, able to provide at least 7 years of registration as of December 2009 and follow-up of vital status as of December 2013. The data were used to compute the limited-duration prevalence, in order to estimate the complete prevalence by means of the COMPREV software.

Results

In 2010, 2,637,975 persons were estimated to live in Italy after a cancer diagnosis, 1.2 million men and 1.4 million women, or 4.6% of the Italian population. A quarter of male prevalent cases had prostate cancer (n = 305,044), while 42% of prevalent women had breast cancer (n = 604,841). More than 1.5 million people (2.7% of Italians) were alive since 5 or more years after diagnosis and 20% since ≥15 years. It is projected that, in 2020 in Italy, there will be 3.6 million prevalent cancer cases (+ 37% vs 2010). The largest 10-year increases are foreseen for prostate (+ 85%) and for thyroid cancers (+ 79%), and for long-term survivors diagnosed since 20 or more years (+ 45%). Among the population aged ≥75 years, 22% will have had a previous cancer diagnosis.

Conclusions

The number of persons living after a cancer diagnosis is estimated to rise of approximately 3% per year in Italy. The availability of detailed estimates and projections of the complete prevalence are intended to help the implementation of guidelines aimed to enhance the long-term follow-up of cancer survivors and to contribute their rehabilitation needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

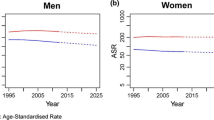

Estimates of cancer prevalence are widely based on limited duration prevalence, including only patients living after a cancer diagnosis made in the previous 5 years [1, 2]. Prevalence, regardless of the time since diagnosis (i.e., complete prevalence), is less frequently estimated than limited duration prevalence [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Overall age-standardized cancer incidence and mortality rates have declined over the past 10 years in the majority of high income countries, whereas the complete prevalence has been consistently increasing in the early 2000s [3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 11]. Complete prevalence is generally measured in absolute numbers and proportions, i.e., not age-standardized. Thus, improved survival [12, 13] and population ageing (increasing absolute number of new cancer diagnoses) imply a progressive increase in tumour prevalence.

Cancer prevalence includes patients currently treated for cancer; those who have become cancer free, but still have a measurable excess risk of recurrence or death; and, finally, patients having death rates similar to those of the general population who can be considered “cured patients” [14]. Many of these individuals are possibly affected by physical, cognitive, and/or psychosocial limitations [15].

The aim of this study was to provide a description of the number of people living in Italy at January 1, 2010 after a cancer diagnosis, for all cancers combined and for a selection of cancer types by sex, age, and time since diagnosis. In addition, projections of cancer prevalence in Italy are presented up to the year 2020. Estimates and projections of complete tumour prevalence and characteristics of prevalent patients are necessary to help clinicians and health care planners in improving long-term care of patients and in allocating appropriately health care resources. Moreover, they may provide helpful information to a growing number of cancer patients or former patients.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This is a descriptive analysis of individual data collected during the period 1976-2009 from 27 population-based Italian cancer registries (i.e., 32% of the entire Italian population in 2010), which agreed to participate in the study and were able to provide at least 7 years of cancer registration as of December 31, 2009 (Appendix 1) and follow-up of vital status as of December 31, 2013. The Italian legislation identifies Cancer Registries as collectors of personal data for surveillance purposes without explicit individual consent. The approval of a research ethic committee is not required, since this descriptive study was conducted without any direct or indirect intervention on patients.

Prevalence for all malignant tumours (ICD-10: C00-C43, C45-C96) and 34 cancer types or their combinations were estimated and presented in this study for all age groups. Urinary bladder cancers with benign or uncertain behaviour, and in situ tumours were also included. Only non melanoma skin cancers (ICD-10 C44) were excluded. ICD-O-3 morphology codes were used to define specific subtypes.

Statistical methods

The clinical and demographic characteristics of the persons registered with a diagnosis of cancers in the Italian CRs were used to estimate: 1) how many of them were still alive at January 1, 2010 regardless of time since diagnosis -i.e., complete prevalence count- by cancer type, sex, and age group; 2) the prevalence proportion in Italy at 2010 for each cancer type, by sex, and age; 3) the complete prevalence (count and proportion) at 1st January 2015 and 2020, overall and by time since diagnosis; and 4) describe the changing over time of these estimates.

For each cancer registry we computed the limited duration prevalence, i.e. the number of patients diagnosed in the period of the registration activity (between 7 and 34 years) at January 1, 2010, using the counting method implemented in SEER*Stat software [16]. This maximum limited duration prevalence was corrected, using the COMPREV software [17], by means of completeness index [18, 19], to estimate the total number of cancer patients alive, regardless of when they were diagnosed. Completeness indices were estimated by cancer type, sex, age, and time since diagnosis. Prevalence was computed as an absolute number, as well as a proportion per 100,000 residents people by cancer type, sex, age group, area of residence, and years since diagnosis. Patients with more than one primary cancer were included in the computation of prevalence for each cancer type or combination. In the analyses for all types combined, only the first cancer was considered. Completeness indices were obtained by statistical regression models of incidence and survival using data from 8 long-term registries (Appendix 1) with an available observation period of at least 18 years before 2010 [20, 21]. Relative survival and incidence functions were estimated by means of parametric models within the period 1985-2011 for survival and 1985-2009 for incidence. The survival model was a parametric cure model assuming that a proportion of individuals with cancer were bound to die (fatal cases) with a survival following a Weibull distribution, while the remaining proportion (cured fraction) had the same mortality rate as that of the general population with the same age and gender stratification [14, 20]. The parameters of the survival model were estimated by cancer type, sex, and age class (0-14, 15-44, 45-54, 55-64, 65-74, 75+ years) through the SAS procedure NLIN. A period effect was included on the hazard of dying of cancer. Incidence data were categorised according to cancer type, sex, five-year age group, and birth cohort (< 1899, 1900-1904,…, 2005-2009). A sixth degree polynomial age-cohort model of crude incidence rates was fitted through the SAS LOGISTIC procedure for each cancer type and sex [21].

Complete prevalence proportions were projected to 2020 by cancer type, sex, age, and registry, assuming that complete prevalence will follow a linear function, based on the trend of the last three calendar years (i.e., 2007-2009). This simplified assumption (linear and constant trend) may not be valid for long-term projections, but it is reasonable for short or medium-term (e.g., 10-year) ones. Other assumptions (e.g., log-linear models) were explored [4, 6], showing consistent results for common cancer types, but unstable projections for the rarest.

The absolute number of prevalent cases in Italy was obtained using proportions of prevalence estimates (age-, sex-, and cancer type-specific) from CRs included in this study, multiplied by the Italian national population by sex and age observed at January 1, 2010. Proportions projected to 2020 were thus multiplied to Italian population forecasted at January 1, 2020 [22].

Results

Prevalence estimates at 2010

In Italy in 2010, 2,637,975 persons were alive after a cancer diagnosis, corresponding to 4.6% of all the Italian population (Appendix 2). Prevalence proportions increase with age: 3.1% at age 45-54 years, 6.6% at 55-64 years, 12.1% at 65-74 years, and nearly 17% after age 75 years (Appendix 2) with differences by sex (Tables 1 and 2).

Men living in Italy after a cancer diagnosis in 2010 were 1,194,033, corresponding to 4.3% (4250/100,000) of all Italian male population (Table 1). This proportion increased from less than 1% below the age of 45 years, to > 20% for men aged ≥75 years. The most frequent tumours in terms of prevalence were prostate (305,044 of prevalent cases at January, 1st 2010) representing 25.5% of all cases or 1.1% of all Italian men, followed by bladder (192,611 men, 16.1%) and colorectal (185,532 men, 15.5%) tumours.

Italian women living after a cancer diagnosis were 1,443,942 (Table 2), corresponding to 4.8% of all Italian women. Breast cancer represented 41.9% of all cancers (604,841), followed by colorectal cancers (171,847, 11.9% of all female prevalent cases, 0.6% of all Italian women) and by endometrial cancers (103,321, 7.2% and 0.3%, respectively). Notably, the fourth most frequent cancer type diagnosed in Italian prevalent women is thyroid (93,341 women, 6.5% of all female prevalent cases). Prevalent women were younger than men. Women aged 15-44 years living after a diagnosis represented 1% of the whole Italian population, they were 4% at ages 45-54 years, 7% at ages 55-64 years, 11% at ages 65-74 years, and 14% for women aged ≥75 years (Table 2).

More than 1.5 million people (i.e., 2.7% of all Italian residents) were alive after ≥5 years since diagnosis. They were 60% of all prevalent cases, 64% of women and 55% of men. The distribution of prevalent cases by time since diagnosis depends on cancer type (Fig. 1). The percentage of prevalent cases diagnosed since less than 2 years varied from 39% for lung cancer patients to 15% for female breast and 7% for cervical cancer patients. Conversely, the percentage of prevalent cases diagnosed ≥15 years before was 59% for cervical cancer, 35% for stomach cancer and 31% for endometrial cancer, but only 4% for prostate and 13% for lung cancer patients. Notably, patients diagnosed ≥15 years before were 21% of all prevalent cases (16% among men and 25% among women).

Prevalence projections for 2020

In 2020, there will be 3.6 million prevalent cancer cases in Italy (Table 3), 1.9 million women and 1.7 million men, with a 10-year increase of 37% (41 and 33% in men and women, respectively). In 2020, 2.6% of all Italian women (0.8 millions) will be alive after a breast cancer diagnosis and more than half a million patients (2.1% of all men) will be alive after a prostate cancer diagnosis (Table 3). The largest 10-year increases are foreseen for prostate (+ 85%) and for thyroid cancers (+ 79%, 212,863 cases), which will become the third most frequent prevalent cancer types among Italian women. A more than 50% increases are also expected in 2020 for prevalence after diagnosis of testicular cancer (63,395 patients) or skin melanoma (169,900). A limited change in prevalence (variations < 10%) is expected for ovary, larynx, and stomach, with cervical cancer being the only cancer type showing a decline in prevalence (− 13%) (Table 3).

Nearly 22% (21,657/100,000) of population aged ≥75 years in 2020 will have had a previous cancer diagnosis (Table 4). Below 45 years of age, prevalent cases will be 228,145 (i.e., 0.8% of all cases, 726/100,000) and, in both sexes, the most frequent cancer type will be thyroid cancer, experienced by 31,971 women and 9141 men.

Prevalent cases diagnosed within 2 years were the only group showing a negligible increase from 2010 to 2020 (+ 3% in the examined period), while a 19% increase was observed for cases diagnosed between 2 and 5 years before, 30-34% for cases diagnosed between 5 and 20 years earlier, and 45% increased for long-term survivors diagnosed ≥20 years before (Fig. 2).

Discussion

In 2010, 2.6 million people were living in Italy after a cancer diagnosis and this number will reach 3.6 million in 2020, increasing from 4.6% to 5.7% (i.e., one out of 17 Italians) of the overall population. The estimated overall trend in the present decade in Italy (+ 3.2% per year) is comparable to that estimated in the same period in the USA (+ 2.8% per year) [5], UK (+ 3.3%) [4], and Switzerland (+ 2.5%) [6].

The expected 37% increase in the present decade in Italy will be more marked (i.e., nearly + 50%) among long-term survivors diagnosed ≥20 years before; they will be more than half a million in Italy (519,356), 14% of all prevalent cases (11% in men and 18% in women). Most of them can be considered as cured since they had already reached a similar life expectancy (i.e., death rates) of the corresponding general population [14].

A higher proportion of women (55%) than that of men emerged among prevalent cancer cases at 2010 in the present Italian study, in agreement with findings from most studies conducted in other countries [4,5,6, 9] but France (where 53% were men, 6.4% of the French population) [8]. In Italy, female breast cancer cases represented 23% of all prevalent cases, and affected the distribution of cancer prevalence by age. The thyroid cancer epidemic in Italy also contributed to an excess in females, below age 45 years thyroid cancer was the most frequent prevalent type in 2010 (29,340 men and women), and this number will substantially increase to more than 41,000 in 2020. It should be noted, however, that a large proportion of thyroid cancer incidence and prevalence may be affected by overdiagnosis; i.e., the detection of cancer cases that would not otherwise result in causing symptoms or deaths [23, 24].

An important role on variation of cancer prevalence is played by screening programmes, inducing a reduction of cervical and colorectal prevalent cancers cases, while early detection of breast and prostate cancers may inflate number of prevalent cases [25]. In particular, screening can prevent cervical cancer, with a consequent major effect on prevalence reduction, i.e., − 13% in 10 years in the present study.

Distribution of cancer prevalence by age is also noteworthy. In 2010, 37% of prevalent patients were 75 years or older (38% in men, 35% in women). In this age group, they will reach 41% in 2020, with more than 20% of men and 14% of women will have experienced a previous cancer diagnosis. These proportions were similar to those reported by other studies, showing also that elderly cancer patients had more severe comorbidity conditions than non cancer patients [26].

At the opposite end of the age spectrum, 8% of Italian prevalent cases were younger than 44 years of age and 10% were aged 45–54 years. It has been recently estimated that 44,135 persons living in Italy in 2010 had had a cancer diagnosis during childhood [27]; they represented 0.07% of the Italian population and 1.7% of prevalent cases diagnosed at any age. In similar studies conducted in the USA [28], a substantial proportion of morbidities emerged in childhood cancer patients several years after diagnosis, and there is growing awareness on potentially long-term risks affecting the survivors’ future physical, cognitive, and/or psychosocial health [29]. The impact of a cancer diagnosis is rather different between younger and older survivors, the first facing more pronounced socio-economic consequences [30, 31], as well as psychosocial impairments in fertility and sexuality [32, 33].

We acknowledge the several limitations of our analyses. First, data from Italian cancer registries (AIRTUM) included one third of the Italian population in 2010 and the representativeness for the national prevalence estimates may be questionable [34]. To overcome this issue, we adjusted estimated proportions in cancer registry areas for the age distribution of the whole Italian population. Moreover, since cancer registries have been active in Italy from a relatively recent time period, the complete prevalence has been estimated through statistical models. Notably, the validation of complete prevalence estimation by means of COMPREV method in Italy and elsewhere [19] is reasonably reassuring. In particular, the validation of COMPREV method shows negligible (i.e., < 5%) differences, when comparing observed prevalence for cancer registries with ≥30 years of observation and estimated prevalence using complete indexes applied to the same registries and truncated data [21, page 34].

On the other hand, the strengths of this population-based study are represented by the size of the study population, which included nearly 1.7 million incident cancer cases, and its long-term follow-up, more than a half of these cases were followed-up for > 20 years post diagnosis. In addition, data and period used were updated in the present study (see Appendix 1), including an additional number of years of observation and follow-up, in comparison with previous studies on the same topic [21].

The accuracy of future projections of prevalence is necessarily uncertain and lies on statistical models based on assumptions reflecting unknown evolution of incidence, survival, and demographic changes. This may also affect comparisons with trends reported in other countries, obtained using different assumptions and statistical models [4, 6, 26]. In our medium-term projections, the hypothesis that complete prevalence at 2020 can be predicted by a linear function of calendar year as regressor variable is supported by empirical evidence, at least for all cancer types combined and for most frequent cancer types, consistently showing an approximate linear trend in recent years [5, 21]. Notably, the use of a longer period (5 calendar years) to estimate linear slope did not materially modify the estimates.

Detailed estimates and projections of numbers of persons living after different cancer diagnoses are particularly relevant for policy makers to better plan health care resource allocation and meet cancer patients needs, including not only initial treatment, but also rehabilitation and long-term surveillance. However, to date, guidelines pertaining to survivorship care have been largely based on consensus rather than on empirical evidence [35,36,37].

In the USA, the main driver of cancer costs growth is population ageing, with an overall increase of 27% by the year 2020 from 2010 levels [38]. The largest increase in expenditures is attributable to the continuing phase of care (i.e., > 1-year post-diagnosis and > 1 year from death) for prostate and female breast cancer, with 42 and 32% increase respectively [38]. Although health care costs in the continuing phase of care is lower than in the first course of treatment (first year since diagnosis) and in the last year of life, the large number of survivors in the continuing phase of care is driving most of healthcare resources. Similar findings, on the distribution of cancer burden by phase of care, are expected in Italy [39].

Conclusions

The availability of reliable and accurate estimates of complete prevalence and predictions of the rising tide of people living after cancer diagnosis may be helpful not only to epidemiologists and health-care planners, but also to clinicians in developing guidelines to enhance and standardize the long-term follow-up of cancer survivors. Furthermore, these estimates are intended for patients to help recovering social activities and supporting rehabilitation demands.

Change history

16 August 2021

The tagging of the family name of Luigino Dal Maso has been updated.

References

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. GLOBOCAN 2012: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012 v1.0. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Available at: http://publications.iarc.fr/Databases/Iarc-Cancerbases/Globocan-2012-Estimated-Cancer-Incidence-Mortality-And-Prevalence-Worldwide-In-2012-V1-0-2012. Accessed 31 Jan 2018.

Crocetti E, De Angelis R, Buzzoni C, Mariotto A, Storm H, Colonna M, Zanetti R, Serraino D, Michiara M, Cirilli C, Iannelli A, Mazzoleni G, Sechi O, Sanoja Gonzalez ME, Guzzinati S, Capocaccia R, Dal Maso L, AIRTUM Working group. Cancer prevalence in United States, Nordic Countries, Italy, Australia, and France: an analysis of geographic variability. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:219–28.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer survival and prevalence in Australia: period estimates from 1982 to 2010. Cancer series no. 69. Cat. no. CAN 65. Canberra: AIHW; 2012.

Maddams J, Utley M, Møller H. Projections of cancer prevalence in the United Kingdom, 2010-2040. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1195–202.

De Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, Alfano CM, Padgett L, Kent EE, Forsythe L, Scoppa S, Hachey M, Rowland JH. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2013;22:561–70.

Herrmann C, Cerny T, Savidan A, Vounatsou P, Konzelmann I, Bouchardy C, Frick H, Ess S. Cancer survivors in Switzerland: a rapidly growing population to care for. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:287. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-287.

Mallone S, De Angelis R, van der Zwan JM, Trama A, Siesling S, Gatta G, Capocaccia R, RARECARE WG. Methodological aspects of estimating rare cancer prevalence in Europe: the experience of the RARECARE project. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:850–6.

Colonna M, Mitton N, Bossard N, Belot A, Grosclaude P, French Network of Cancer Registries (FRANCIM). Total and partial cancer prevalence in the adult French population in 2008. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:153.

Hovaldt HB, Suppli NP, Olsen MH, Steding-Jessen M, Hansen DG, Møller H, Johansen C, Dalton SO. Who are the cancer survivors? A nationwide study in Denmark, 1943-2010. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:1549–53.

Parry C, Kent EE, Mariotto AB, Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Cancer survivors: a booming population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011;20:1996–2005.

Gatta G, Mallone S, van der Zwan JM, Trama A, Siesling S, Capocaccia R, EUROCARE Working Group. Cancer prevalence estimates in Europe at the beginning of 2000. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1660–6.

De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman MP, Francisci S, Baili P, Pierannunzio D, Trama A, Visser O, Brenner H, Ardanaz E, Bielska-Lasota M, Engholm G, Nennecke A, Siesling S, Berrino F, Capocaccia R, EUROCARE-5 Working Group. Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE-5, a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:23–34.

Allemani C, Weir HK, Carreira H, Harewood R, Spika D, Wang XS, Bannon F, Ahn JV, Johnson CJ, Bonaventure A, Marcos-Gragera R, Stiller C, Azevedo e Silva G, Chen WQ, Ogunbiyi OJ, Rachet B, Soeberg MJ, You H, Matsuda T, Bielska-Lasota M, Storm H, Tucker TC, Coleman MP, CONCORD Working Group. Global surveillance of cancer survival 1995-2009: analysis of individual data for 25,676,887 patients from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries (CONCORD-2). Lancet. 2015;385:977–1010. Erratum in: Lancet. 2015;385:946

Dal Maso L, Guzzinati S, Buzzoni C, Capocaccia R, Serraino D, Caldarella A, Dei Tos AP, Falcini F, Autelitano M, Masanotti G, Ferretti S, Tisano F, Tirelli U, Crocetti E, De Angelis R, AIRTUM Working group. Long-term survival, prevalence, and cure of cancer: a population-based estimation for 818902 Italian patients and 26 cancer types. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:2251–60.

De Santis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, Alteri R, Robbins AS, Jemal A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:252–71.

SEER*Stat Software, Version 8.3.2 released April 2016. National Cancer Institute. Available: http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/. Accessed 31 Jan 2018.

Complete Prevalence (ComPrev) Software, Version 2.0 released April 2011. National Cancer Institute. Available: http://surveillance.cancer.gov/comprev/. Accessed 31 Jan 2018.

Capocaccia R, De Angelis R. Estimating the completeness of prevalence based on cancer registry data. Stat Med. 1997;16:425–40.

Merrill RM, Capocaccia R, Feuer EJ, Mariotto A. Cancer prevalence estimates based on tumour registry data in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:197–207.

De Angelis R, Capocaccia R, Hakulinen T, Soderman B, Verdecchia A. Mixture models for cancer survival analysis: application to population-based data with covariates. Stat Med. 1999;18:441–54.

AIRTUM Working Group. Italian cancer figures, report 2014. Prevalence and cure of cancer in Italy. Epidemiol Prev. 2014;38(Suppl 1):S1–S144. Available at http://www.registri-tumori.it/cms/it/Rapp2014. Accessed 31 Jan 2018. See also http://www.registri-tumori.it/cms/?q=Rapp2010.

ISTAT. Demografia in cifre. Available: http://www.demo.istat.it. Accessed 31 Jan 2018.

Ahn HS, Kim HJ, Kim KH, Lee YS, Han SJ, Kim Y, MJ KO, Brito JP. Thyroid cancer screening in South Korea increases detection of papillary cancers with no impact on other subtypes or thyroid cancer mortality. Thyroid. 2016;26:1535–40.

Vaccarella S, Franceschi S, Bray F, Plummer M, Dal Maso L. Worldwide thyroid-cancer epidemic? The increasing impact of overdiagnosis. New Engl J Med. 2016;375:614–7.

Shieh Y, Eklund M, Sawaya GF, Black WC, Kramer BS, Esserman LJ. Population-based screening for cancer: hope and hype. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:550–65.

Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2016;25:1029–36.

Francisci S, Guzzinati S, Dal Maso L, Sacerdote C, Buzzoni C, Gigli A, AIRTUM Working Group. An estimate of the number of people in Italy living after a childhood cancer. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:2444–50.

Phillips SM, Padgett LS, Leisenring WM, Stratton KK, Bishop K, Krull KR, Alfano CM, Gibson TM, de Moor JS, Hartigan DB, Armstrong GT, Robison LL, Rowland JH, Oeffinger KC, Mariotto AB. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2015;24:653–63.

Zeltzer LK, Lu Q, Leisenring W, Tsao JC, Recklitis C, Armstrong G, Mertens AC, Robison LL, Ness KK. Psychosocial outcomes and health-related quality of life in adult childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17:435–46.

Dumas A, Berger C, Auquier P, Michel G, Fresneau B, Setcheou Allodji R, Haddy N, Rubino C, Vassal G, Valteau-Couanet D, Thouvenin-Doulet S, Casagranda L, Pacquement H, El-Fayech C, Oberlin O, Guibout C, de Vathaire F. Educational and occupational outcomes of childhood cancer survivors 30 years after diagnosis: a French cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:1060–8.

Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Jenkinson H, Winter DL, Kelly J, Reulen RC, Hawkins MM, British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (BCCSS) Steering Group. Employment status and occupational level of adult survivors of childhood cancer in Great Britain: the British childhood cancer survivor study. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:2678–92.

Armuand G, Skoog-Svanberg A, Bladh M, Sydsjö G. Reproductive patterns among childhood and adolescent cancer survivors in Sweden: a population-based matched-cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(14):1577–83.

Jacobs LA, Pucci DA. Adult survivors of childhood cancer: the medical and psychosocial late effects of cancer treatment and the impact on sexual and reproductive health. J Sex Med. 2013;10(Suppl 1):120–6.

Guzzinati S, Buzzoni C, De Angelis R, Rosso S, Tagliabue G, Vercelli M, Pannozzo F, Mangone L, Piffer S, Fusco M, Giacomin A, Traina A, Capocaccia R, Dal Maso L, Crocetti E, AIRTUM working group. Cancer prevalence in Italy: an analysis of geographic variability. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1497–510.

Howell D, Hack TF, Oliver TK, Chulak T, Mayo S, Aubin M, Chasen M, Earle CC, Friedman AJ, Green E, Jones GW, Jones JM, Parkinson M, Payeur N, Sabiston CM, Sinclair S. Models of care for post-treatment follow-up of adult cancer survivors: a systematic review and quality appraisal of the evidence. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:359–71.

AA.VV. 2015. Consensus Conference “Dalla pratica del Follow up alla cultura di Survivorship care”, Disponibile su http://www.aiom.it/professionisti/documenti-scientifici/position-paper/consensus-follow-up-2015/1,763,1. Accessed 31 Jan 2018.

Laudicella M, Walsh B, Burns E, Smith PC. Cost of care for cancer patients in England: evidence from population-based patient-level data. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:1286–92.

Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–28.

Gigli A, Warren JL, Yabroff KR, Francisci S, Stedman M, Guzzinati S, Giusti F, Miccinesi G, Crocetti E, Angiolini C, Mariotto A. Initial treatment for newly diagnosed elderly colorectal cancer patients: patterns of Care in Italy and the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2013;46:88–98.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mrs. Luigina Mei for editorial assistance.

Funding

The study was funded by the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) (grant no. 16921). Role of funding source: The funding sources had no role in study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Availability of data and materials

Dataset supporting our findings is available, according to AIRTUM guidelines, at the following website: www.registri-tumori.it.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Author notes

Adriano Giacomin is deceased.

- Adriano Giacomin

Contributions

SG and LDM drafted the study protocol, designed the study, and drafted the manuscript with the support of RDA. All authors (SG, SV, RDA, CP, CB, RC, SiF, AnG, MZ, GT, DS, FF, CC, AGR, FaS, BC, MM, ALC, MC, StF, LM, GR, FlS, GM, FaP, MF, RT, PR, GG, AdG, FT, GC, ACF, FiP, ASS, MR, LB, LDM) and AIRTUM Working Group revised the study protocol, collected data, prepared raw data for the study database, and corrected data after quality controls. SG did the statistical analyses with the support of SV, CP, LB and LDM. DS, RC, SiF, AG specifically supported LDM in the interpretation and clinical implication of study results. All authors revised the preliminary results and the report, and contributed to data interpretation, report writing, and reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Italian legislation identifies Cancer Registries as collectors of personal data for surveillance purposes without explicit individual consent. The approval of a research ethic committee is not required, since this study is a descriptive analysis of individual data without any direct or indirect intervention on patients (Decreto del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri, 3/3/2017, Identificazione dei sistemi di sorveglianza e dei registri di mortalità, di tumori e di altre patologie, 17A03142, GU Serie Generale n.109 del 12-05-2017 (Available at: http://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/05/12/17A03142/sg, last access: 31/01/2018).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Guzzinati, S., Virdone, S., De Angelis, R. et al. Characteristics of people living in Italy after a cancer diagnosis in 2010 and projections to 2020. BMC Cancer 18, 169 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4053-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4053-y