Abstract

Background

This study aimed to evaluate the long-term outcome and toxicities in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) treated by concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) with/without adding cetuximab.

Methods

A total of 62 patients treated with CCRT plus cetuximab were matched with 124 patients treated with CCRT alone by age, sex, pathological type, T category, N category, disease stage, radiotherapy (RT) technique, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA levels, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG). Overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), locoregional recurrence-free survival (LRFS), and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) were assessed using the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test. Treatment toxicities were clarified and compared between two groups.

Results

A total of 186 well-balanced stage II to IV NPC patients were retrospectively analyzed (median follow-up, 76 months). Compared to CCRT alone, adding cetuximab resulted in more grade 3 to 4 radiation mucositis (51.6% vs. 23.4%; P < 0.001). No differences were found between the CCRT + cetuximab group and the CCRT group in 5-year OS (89.7% vs. 90.7%, P = 0.386), 3-year PFS (83.9% vs. 88.7%, P = 0.115), the 3-year LRFS (95.0% vs. 96.7%, P = 0.695), and the 3-year DMFS (88.4% vs 91.9%, P = 0.068). Advanced disease stage was the independent prognostic factor predicting poorer OS and PFS.

Conclusion

Adding cetuximab to CCRT did not significantly improve benefits in survival in stage II to IV NPC and exacerbated acute mucositis and acneiform rash. Further investigations are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is an endemic carcinoma in Southern China and Southeast Asia, especially in the Guangdong province, with an annual incidence of 20–30 per 100,000 population [1,2,3]. Radiotherapy (RT) is the primary treatment, and several prospective randomized trials and meta-analyses have supported the use of combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology recommended concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) with or without adjuvant chemotherapy as the standard treatment protocol for stage II–IV NPC [11].

Despite improved treatment modalities and techniques yielding excellent survival outcomes, 20%–30% of patients die of distant and/or local-regional relapse [12]. To improve this result, therapies involving molecular targets such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) have been studied extensively over the last decade. High levels of EGFR have been observed in 80% of patients with locoregionally advanced NPC and it is associated with poor clinical outcome [13]. Cetuximab, an anti-EGFR antibody, showed a survival benefit in patients with locoregionally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) when combined with RT [14]. In NPC, a phase II study showed that cetuximab combined with carboplatin demonstrates clinical activity for recurrent or metastatic NPC patients with previous treatment failure with platinum-based therapy [15]. The preliminary report of the ENCORE study demonstrated a promising clinical response in using cetuximab combined with CCRT in NPC [16]. A phase II study conducted by Ma et al. reported that concurrent cetuximab-cisplatin and intensity-modulated radiotherapy in locoregionally advanced NPC was feasible and preliminary survival outcomes compared favorably with historic data [17].

However, currently there are still no randomized trials that have been conducted to directly compare the outcome of CCRT alone versus concomitant cetuximab as a first-line treatment of Stage II to IVb NPC. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to compare the long-term outcome and toxicities of the NPC patients treated by CCRT with or without adding cetuximab used as a matched case-control study.

Methods

Patients diagnosed with nasopharyngeal carcinoma at our institution between January 2007 and April 2014 were identified, as a total of 7385 patients. The eligibility criteria included the following: (1) untreated, newly diagnosed NPC without distant metastasis; (2) biopsy- confirmed World Health Organization (WHO) type II-III NPC; (3) 18 ~ 70 years old; (4) without secondary malignancy, pregnancy, or lactation. Ultimately, 1971 patients were included in the study population, of them 1909 patients received CCRT alone, and only 62 patients received CCRT with cetuximab due to the expensive cost of treatment. In the 1:2 match, patients who received cetuximab plus CCRT were individually matched to two control patients receiving CCRT alone according to age, sex, pathological type, T category, N category, disease stage, RT technique, EBV DNA levels, and ECOG. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Fig. 1.

Pretreatment assessments

All patients were evaluated by a complete physical assessment, hematologic and biochemical profiles, nasopharyngoscopy, MRI or enhanced CT of the nasopharynx and neck (CT was only used in patients with contraindication to MRI), chest scan (X-ray or CT), abdominal sonography, bone scan, and plasma level of EBV DNA. The plasma level of EBV DNA was measured by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [18, 19].

Concurrent chemotherapy and cetuximab

All patients were treated with CCRT using cisplatin chemotherapy. Cisplatin was administered at 80 ~ 100 mg/m2 triweekly for at least 2 cycles or at 30 ~ 40 mg/m2 weekly for 5 ~ 7 cycles during radiotherapy. In the CCRT group, 64 (51.6%) patients received 80–100 mg/m2 cisplatin triweekly and 60 (48.4%) received 30–40 mg/m2 cisplatin weekly. In the CCRT plus cetuximab group, 39 (62.9%) patients received triweekly cisplatin, while weekly cisplatin was administered to 23 (37.1%) patients. The patients in the cetuximab plus CCRT group received a loading dose of cetuximab 400 mg/m2 1 week before RT and thereafter a weekly dose of 250 mg/m2 during RT for 6 ~ 7 cycles of treatment.

Radiotherapy

All patients were treated with radiotherapy delivered as five fractions per week, among them, 30 patients underwent conventional RT using two-dimensional technique (2D–CRT) and 156 patients received intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). Details of the RT techniques applied at our Cancer Center at Sun Yat-Sen University have been reported previously [20, 21] in conformity with the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements Reports 50 and 62. The patients treated with 2D–CRT received total radiation doses of 70–76 Gy to the primary tumor at 2 Gy per fraction, 62–66 Gy to the involved areas of the neck, and 50 Gy to the uninvolved areas. The patients received IMRT with variable 2.12 to 2.24 Gy fractions daily for 5 days per week up to a total of 68–72 Gy (median 70 Gy).

Outcome and follow-up

The primary endpoint for this study was overall survival (OS), which was calculated from the date of treatment to the date of death from any cause. The secondary endpoints for the study were progression-free survival (PFS), distant failure-free survival (DMFS), locoregional failure-free survival (LRFS), and toxicity profile. PFS was calculated from the date of treatment to the date of locoregional failure, distant failure, or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. DMFS was defined as the date of treatment to first distant metastasis, and LRFS was defined as the date of treatment to first locoregional relapse. The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0 was used to grade treatment-related acute toxicities. Acute and late radiation-related complications were scored according to the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG)/the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Late Radiation Morbidity Scoring Schema [22]. All the patients were followed after treatment. Patients were evaluated every 3 months during the first 2 years, and then every 6 months thereafter until death.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (Version 22.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The actuarial survival rates were described with Kaplan–Meier method and survival curves were compared with the log-rank test. Fisher’s exact tests and χ2 test were used to assess categorical variables, and hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards models. Covariates included in the univariate and multivariate analyses were smoking history, disease stage, EBV DNA level, VCA-IgA, EA-IgA, BMI, C-reactive protein (CRP), and family history of cancer. All statistical tests were two-sided, and the criterion for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics and treatment compliance

A total of 168 patients were enrolled in this study. There were 62 cases in the cetuximab plus CCRT group and 124 controls. The groups were well matched for age, sex, pathological type, T category, N category, disease stage, RT technique, EBV DNA levels, and ECOG. Patient characteristics and treatment factors are detailed in Table 1. All patients completed planned RT. In terms of chemotherapy, 103 patients received triweekly cisplatin, among whom 39 (62.9%) and 64 (51.6%) patients were from cetuximab plus CCRT group and CCRT group, respectively. The remaining 83 patients received weekly cisplatin, with 23 (37.1%) patients from cetuximab plus CCRT group and 60 (48.4%) patients from CCRT group. In cetuximab plus CCRT group and CCRT group, 60 (96.8%) and 120 (96.8%) patients received at least 2 cycles of triweekly cisplatin or 5 cycles of weekly cisplatin, respectively. Appendix 1: Table 6 lists the specifics of chemotherapy in both groups. The percentages of patients dropping out from treatment due to toxicities were non-significantly different between the two groups. In the group of adding cetuximab, 52 (83.9%) patients received six or more weekly cetuximab doses. 9 (14.5%) patients stopped using cetuximab as a result of toxicity.

Toxicities

Table 2 lists the distribution of adverse effects. Significant differences only in terms of mucositis were observed between the two treatment groups (51.6% with cetuximab vs. 23.4% without; P < 0.001). The rate of 10% weight loss was statistically different (66.1% with cetuximab vs. 50.8% without; P = .047). The incidence of cetuximab-related acneiform rash in the cetuximab group was 75.8%. Grade 2 cetuximab-related acneiform rash in the CCRT with cetuximab group was reported in 15 (24.2%) patients. Only one (1.6%) patient developed grade 3 acneiform rash toxic effect and no patient had grade 4 toxic effect. No patient in the CCRT group had acneiform rash. No significant differences of grade 3–4 toxicity in neutropenia, neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, liver and kidney dysfunction, dermatitis, vomiting, or weight loss were found between the two groups. With respect to late complications, no significant differences of grade 2–4 toxicity in xerostomia and hearing loss were found between the two groups. (Table 3.)

Survival

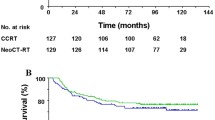

The median follow-up duration for the entire cohort was 76 months (range, 4–114 months), 76 months (range, 4–107 months) for the cetuximab plus CCRT group, and 76 months (range, 5–114 months) for the controls. No significant differences were found between groups in OS, PFS, LRFS, or DMFS (Table 4, Fig. 2.). The 5-year probabilities for OS were 89.7% (95% CI, 81.9% to 97.5%) for the CCRT with cetuximab group and 90.7% (95% CI, 85.4% to 96.0%) for the CCRT group (P = 0.386). The 3-year PFS rates of the CCRT with cetuximab group and the CCRT group were 83.9% (95% CI, 74.7% to 93.1%) and 88.7% (95% CI, 83.0% to 94.4%) (P = 0.115), respectively. The 3-year LRFS and DMFS rates of the CCRT with cetuximab group vs. the CCRT group were 95.0% (95% CI, 89.5% to 100%) vs. 96.7% (95% CI, 93.6% to 99.8%) (P = 0.695), 88.4% (95% CI, 80.4% to 96.4%) vs. 91.9% (95% CI, 87.0% to 96.8%) (P = 0.068), respectively.

Multiple variables including familial history, smoking history, body mass index (BMI), tumor factors (i.e., disease stage, EBV DNA levels, VCA-IgA, and EA-IgA), and intervention (i.e., whether using cetuximab) were analyzed by a multivariable analysis to predict outcomes for the whole population. Advanced disease stage was an independent prognostic factor predicting poorer OS and PFS (Table 5).

Discussion

Controversy remains regarding the additional benefit of cetuximab to concomitant chemoradiotherapy, which is the primary regimen for stage II–IV NPC. Appendix 2: Table 7. listed the related studies. Our matched case-control study aimed to clarify the feasibility and efficacy of cetuximab combined with CCRT among stage II–IV NPC patients.

Historically, the treatment of HNSCC with concurrent cetuximab and RT provides survival benefit when compared to RT alone. Bonner et al. conducted a multinational, randomized study to compare radiotherapy alone with radiotherapy plus cetuximab in the treatment of locoregionally advanced squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck, which found a survival advantage associated with the use of cetuximab delivered in conjunction with radiation [14]. However, a large randomized phase III trial of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 0522 [23] in head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma (HNSCC), which tested whether the addition of cetuximab to cisplatin-RT were more effective, demonstrated that no discernable benefit and an increase in toxicity from adding cetuximab to radiation-cisplatin and hence should not be prescribed routinely.

In NPC, to date, studies in terms of cetuximab added to CCRT in NPC have been conducted showing that it is safe, effective, and tolerated [17, 24], while none of them was with a direct comparison of CCRT. An retrospective matched case–control study [25] on concurrent cetuximab-based bioradiotherapy (BRT) or cisplatin-based chemoradiotherapy (CRT) in patients with NPC suggested equivalence between these two treatments. In this study, the 5-year OS rates in patients in the BRT group was similar to patients treated with CRT (79.5% vs. 79.3%, P = 0.797). T. Xu et al. earlier reported a randomized phase II study [26] on patients with NPC who received concurrent cetuximab-based radiotherapy (ERT). This study demonstrated that ERT was not more efficacious than concurrent cisplatin-IMRT. In our study, we also disappointed to discover that patients in CCRT + cetuximab group achieved a 5-year OS rate similar to patients treated with re-RT+/−chemotherapy (89.7% vs. 90.7%, P = 0.386), and in PFS, LRFS, or DMFS there are also no significant improvements. Survival outcomes in this study seemed much higher than our experience [17, 24, 27] with concurrent cisplatin and radiotherapy—either with or without cetuximab. It may be due to an unbalanced distribution of disease stages in our study, in which the percentages of II, III, and IV stage patients were 8.1%, 75.8%, and 16.1%, respectively. Faced with these negative results, a plausible explanation could be that cetuximab and cisplatin have similar mechanisms of radiation sensitization [28, 29]. So tumors turned out to be resistant to both agents, and sensitive tumors would derive no additional benefit. In further study, refine study populations based on some new biologic tumor features or biomarkers, which were proved to be associated with radiation resistance or metastasis, to define patients who will benefit from cetuximab should be carefully considered.

In regard to toxicity, mucositis is the most common toxicity reported by studies regarding cetuximab combined with radiotherapy in head and neck. Notwithstanding, a pivotal trial by Bonner suggested that cetuximab did not exacerbate mucositis associated with radiotherapy of the head and neck [14]. In daily practice, though not clearly supported in the literature, the rate of mucositis with RT/CRT plus cetuximab seems higher, especially in Asians. Ethnic and lifestyle habits may play a role [30]. A randomized phase II study [26] mentioned before showed using cetuximab with RT was more likely to cause grade 3/4 oral mucositis than cisplatin-based CRT in locally advanced NPC. Ma et al. [17] also reported that using cetuximab with CCRT caused a high rate of grade 3–4 mucositis of 87% in locally advanced NPC. In this study, we found that the incidence of moderate-to-severe mucositis in the CCRT with cetuximab group was significantly higher than that in the CCRT group (51.6% vs. 23.4%, P < 0.05). The possible mechanism why cetuximab plus cisplatin add more severe oral mucositis are as followed. The epithelial cells of the oral mucosa are susceptible to the effects of cytotoxic therapy. Cisplatin can interfere with cellular mitosis and reduce the ability of the oral mucosa to regenerate [30], while cetuximab is considered to be able to enhance cytotoxic drug activity. Moreover, as patients in this study received cisplatin in two ways (triweekly and weekly), we have performed a subgroup analysis to rule out the effect of different dose schedule of cisplatin on toxicities. The finding of this stratified analysis showed that cetuximab significantly increased mucositis of NPC patients receiving CRT with triweekly cisplatin, while in weekly cisplatin delivery subgroup, the incidence of grade 3–4 mucositis in CCRT with cetuximab group and CCRT group were 30.4% and 21.7% (P = 0.403), respectively (Appendix 3: Table 8). The hematological and other non-hematological adverse events were similar between groups. Ma et al. [17] reported in a single arm retrospective study that the treatment safety was achieved when adding cetuximab to concurrent cisplatin and IMRT in locally advanced NPC. Adding cetuximab and using IMRT were the two prognostic factors predicting severe acute toxicities in this study, while earlier age and 2D–RT were the two prognostic factors predicting severe late toxicities in this study. (Appendix 4: Table 9.)

Multivariable analysis identified stage IV as an independent predictors of poor prognosis. It revealed that adding cetuximab to CCRT was not associated with a lower risk of death and disease progression than CCRT alone. Considering no survival benefit and greater toxicities, cetuximab with CCRT as the first-line treatment should be used with caution and more evidence is needed to guide the use of cetuximab in NPC.

However, there are several limitations to our study. First, the size of our study is relatively small, which might make the results of the study underpowered and selection bias might exist. Second, our study was retrospective and carried out at a single center. Although we tried to decrease potential bias by increasing the numbers in the control group, there is inevitable bias caused by its retrospective nature. Third, we did not rigorously match the delivery method of cisplatin; however, studies [31, 32] have demonstrated that radiation with concurrent cisplatin administered weekly or every 3 weeks leads to similar deliverability, toxicity profiles, and outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that patients with stage II-IV NPC receiving CCRT with cetuximab did not achieve a benefit to survival compared to patients treated with CCRT alone, while adding cetuximab to CCRT exacerbated acute mucositis and acneiform rash. Therefore, multicenter prospective randomized clinical trials with refining study populations are warranted for further investigation.

Abbreviations

- 2D–CRT:

-

Two-dimensional conventional radiotherapy

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BRT:

-

Bioradiotherapy

- CCRT:

-

Concurrent chemoradiotherapy

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DMFS:

-

Distant metastasis-free survival

- EBV:

-

Epstein-Barr virus

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- HNSCC:

-

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HRs:

-

Hazard ratios

- IMRT:

-

Intensity-modulated radiotherapy

- LRFS:

-

Locoregional recurrence-free survival

- NPC:

-

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- R/M NPC:

-

Recurrent and/or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- RT:

-

Radiotherapy

- RTOG:

-

Radiation Therapy Oncology Group

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Wee J, Ha TC, Loong S, Qian C. Is nasopharyngeal cancer really a “Cantonese cancer”? Chin J Cancer. 2010;29(5):517–26.

Mimi CY, Yuan J-M. Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12(6):421–9.

Wei WI, Sham JS. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2005;365(9476):2041–54.

Lee AW, Tung SY, Chan AT, Chappell R, Fu Y-T, Lu T-X, Tan T, Chua DT, O’Sullivan B, Xu SL. Preliminary results of a randomized study (NPC-9902 Trial) on therapeutic gain by concurrent chemotherapy and/or accelerated fractionation for locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(1):142–51.

Lin J-C, Jan J-S, Hsu C-Y, Liang W-M, Jiang R-S, Wang W-Y. Phase III study of concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: positive effect on overall and progression-free survival. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(4):631–7.

Lin J, Jan J, Hsu C, Jiang R, Wang W. Outpatient weekly neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy for advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: high complete response and low toxicity rates. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(2):187–94.

Al-Sarraf M, LeBlanc M, Giri P, Fu KK, Cooper J, Vuong T, Forastiere AA, Adams G, Sakr WA, Schuller DE. Chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal cancer: phase III randomized intergroup study 0099. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(4):1310–7.

Chan A, Teo P, Ngan R, Leung T, Lau W, Zee B, Leung S, Cheung F, Yeo W, Yiu H. Concurrent chemotherapy-radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: progression-free survival analysis of a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(8):2038–44.

Huncharek M, Kupelnick B. Combined chemoradiation versus radiation therapy alone in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: results of a meta-analysis of 1,528 patients from six randomized trials. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25(3):219–23.

Baujat B, Audry H, Bourhis J, Chan AT, Onat H, Chua DT, Kwong DL, Al-Sarraf M, Chi K-H, Hareyama M. Chemotherapy in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an individual patient data meta-analysis of eight randomized trials and 1753 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(1):47–56.

Forastiere AA, Ang K, Brizel D, Brockstein BE, Dunphy F, Eisele DW, Goepfert H, Hicks WL, Kies MS, Lydiatt WM. Head and neck cancers: Clinical practice guidelines. JNCCN Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2005;3(3):316–391.

Sun X, Su S, Chen C, Han F, Zhao C, Xiao W, Deng X, Huang S, Lin C, Lu T. Long-term outcomes of intensity-modulated radiotherapy for 868 patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an analysis of survival and treatment toxicities. Radiother Oncol. 2014;110(3):398–403.

Feng H-X, Guo S-P, Li G-R, Zhong W-H, Chen L, Huang L-R, Qin H-Y. Toxicity of concurrent chemoradiotherapy with cetuximab for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2014;31(9):1–6.

Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, Azarnia N, Shin DM, Cohen RB, Jones CU, Sur R, Raben D, Jassem J. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):567–78.

Chan AT, Hsu M-M, Goh BC, Hui EP, Liu T-W, Millward MJ, Hong R-L, Whang-Peng J, Ma BB, To KF. Multicenter, phase II study of cetuximab in combination with carboplatin in patients with recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3568–76.

Lu T, Zhao C, Chen C, Gao L, Lang J, Pan J, Hu C, Jin F, Wang R, Xie C. An open, multicenter clinical study on cetuximab combined with intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) plus concurrent chemotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC): preliminary report. J Clin Oncol. 2010;2010:5577.

Ma BB, Kam MK, Leung SF, Hui EP, King AD, Chan SL, Mo F, Loong H, Yu BK, Ahuja A, et al. A phase II study of concurrent cetuximab-cisplatin and intensity-modulated radiotherapy in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(5):1287–92.

Shao JY, Li YH, Gao HY, Wu QL, Cui NJ, Zhang L, Cheng G, Hu LF, Ernberg I, Zeng YX. Comparison of plasma Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) DNA levels and serum EBV immunoglobulin a/virus capsid antigen antibody titers in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100(6):1162–70.

An X, Wang FH, Ding PR, Deng L, Jiang WQ, Zhang L, Shao JY, Li YH. Plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA level strongly predicts survival in metastatic/recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with palliative chemotherapy. Cancer. 2011;117(16):3750–7.

Zhao C, Han F, Lu L, Huang S, Lin C, Deng X, Lu T, Cui N. [Intensity modulated radiotherapy for local-regional advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma]. Ai zheng= Aizheng= Chinese journal of cancer. 2004;23(11 Suppl):1532–1537.

Ma J, Mai H-Q, Hong M-H, Min H-Q, Mao Z-D, Cui N-J, Lu T-X, Mo H-Y. Results of a prospective randomized trial comparing neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radiotherapy with radiotherapy alone in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(5):1350–7.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 4.0. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. 2009;4(03).

Ang KK, Zhang Q, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tan PF, Sherman EJ, Weber RS, Galvin JM, Bonner JA, Harris J, El-Naggar AK. Randomized phase III trial of concurrent accelerated radiation plus cisplatin with or without cetuximab for stage III to IV head and neck carcinoma: RTOG 0522. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):2940–50.

Niu X, Hu C, Kong L. Experience with combination of cetuximab plus intensity-modulated radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139(6):1063–71.

Wu X, Huang J, Liu L, Li H, Li P, Zhang J, Xie L. Cetuximab concurrent with IMRT versus cisplatin concurrent with IMRT in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a retrospective matched case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(39):e4926.

Xu T, Liu Y, Dou S, Li F, Guan X, Zhu G. Weekly cetuximab concurrent with IMRT aggravated radiation-induced oral mucositis in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: results of a randomized phase II study. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(9):875–9.

Sun Y, Li W-F, Chen N-Y, Zhang N, Hu G-Q, Xie F-Y, Sun Y, Chen X-Z, Li J-G, Zhu X-D, et al. Induction chemotherapy plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a phase 3, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2016;17(11):1509–20.

Dittmann K, Mayer C, Fehrenbacher B, Schaller M, Raju U, Milas L, Chen DJ, Kehlbach R, Rodemann HP. Radiation-induced epidermal growth factor receptor nuclear import is linked to activation of DNA-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(35):31182–9.

Kvols LK. Radiation sensitizers: a selective review of molecules targeting DNA and non-DNA targets. J Nucl Med. 2005;46(1 suppl):187S–90S.

Zhu G, Lin J-C, Kim S-B, Bernier J, Agarwal JP, Vermorken JB, Thinh DHQ, Cheng H-C, Yun HJ, Chitapanarux I. Asian expert recommendation on management of skin and mucosal effects of radiation, with or without the addition of cetuximab or chemotherapy, in treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):42.

Jagdis A, Laskin J, Hao D, Hay J, Wu J, Ho C. Dose delivery analysis of weekly versus 3-weekly cisplatin concurrent with radiation therapy for locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37(1):63–9.

Tao C-J, Lin L, Zhou G-Q, Tang L-L, Chen L, Mao Y-P, Zeng M-S, Kang T-B, Jia W-H, Shao J-Y. Comparison of long-term survival and toxicity of cisplatin delivered weekly versus every three weeks concurrently with intensity-modulated radiotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110765.

Acknowledgements

We kindly thank the editor and reviewers for careful review and valuable comments, which have led to a significant improvement of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81425018, No.81672863, No. 81072226, and No. 81201629), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC0902000), the National Key Basic Research Program of China (No. 2013CB910304), the Special Support Plan of Guangdong Province (No. 2014TX01R145), the Sci-Tech Project Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2014A020212103 and No. 2011B080701034), the Health & Medical Collaborative Innovation Project of Guangzhou City (No. 201400000001), the National Science & Technology Pillar Program during the Twelfth Five-Year Plan Period (No. 2014BAI09B10), the Sun Yat-Sen University Clinical Research 5010 Program, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HQM and CZ carried out the study concepts; HQM and YL participated in study design; HQM, YL and QYC participated in data acquisition; HQM, YL, QYC and LQT participated in quality control of data and algorithms; YL participated in data analysis and interpretation; YL and QYC participated in statistical analysis; YL, QYC, LQT, LTL and SSG participated in interpretation of data; YL, QYC, LQT, LTL, SSG, LG and HYM participated in manuscript editing; YL, QYC, HQM, LQT, LTL, SSG, LG, HYM, MYC, XG, KJC, CNQ, MSZ, JXB, JYS, YS, JT, SC, CZ and JM participated in manuscript review for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved by the Clinical Research Committee of Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center, China. All of the participants provided written informed consent before treatment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Chen, QY., Tang, LQ. et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with or without cetuximab for stage II to IVb nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a case–control study. BMC Cancer 17, 567 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3552-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3552-6