Abstract

Background

Prognostic factors aid in the stratification and treatment of cancer. This study evaluated prognostic importance of tumor infiltrating immune cell in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Methods

Profiles of infiltrating immune cells and clinicopathological data were available for 78 OSCC patients with a median follow-up of 48 months. The infiltrating intensity of CD8, CD4, T-bet, CD68 and CD57 positive cells were assessed by immunohistochemistry. Chi-square test was used to compare immune markers expression and clinicopathological parameters. Univariate and multivariate COX proportional hazard models were used to assess the prognostic discriminator power of immune cells. The predictive potential of immune cells for survival of OSCC patients was determined using ROC and AUC.

Results

The mean value of CD8, CD4, T-bet, CD68 and CD57 expression were 28.99, 62.06, 8.97, 21.25 and 15.75 cells per high-power field respectively. The patient cohort was separated into low and high expression groups by the mean value. Higher CD8 expression was associated with no regional lymph node metastasis (p = 0.033). Patients with more abundant stroma CD57+ cells showed no metastasis into regional lymph node (p = 0.005), and early clinical stage (p = 0.016). The univariate COX regression analyses showed that no lymph node involvement (p < 0.001), early clinical stage (TNM staging I/II vs III/IV, p = 0.007), higher CD8 and CD57 expression (p < 0.001) were all positively correlated with longer overall survival. Multivariate COX regression analysis showed that no lymph node involvement (p = 0.008), higher CD8 (p = 0.03) and CD57 (p < 0.001) expression could be independent prognostic indicators of better survival. None of CD4, T-bet or CD68 was associated with survival in ether univariate or multivariate analysis. ROC and AUC showed that the predictive accuracy of CD8 and CD57 were all superior compared with TNM staging. CD57 (AUC = 0.868; 95% CI, 0.785–0.950) and CD8 (AUC = 0.784; 95% CI, 0.680–0.889) both provided high predictive accuracy, of which, CD57 was the best predictor.

Conclusion

Tumor stroma CD57 and CD8 expression was associated with lymphnode status and independently predicts survival of OSCC patients. Our results suggest an active immune microenvironment in OSCC that may be targetable by immune drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with head and neck cancer. Even with multi-modality treatment, only modest improvement of patient survival has been reported. To date, the prognosis of OSCC patients remains unsatisfactory, as indicated by the poor 5-year survival rate of less than 20% in advanced patients [1,2,3]. Such a poor survival in OSCC patients indicates not only the aggressiveness of this cancer, but also insufficient understanding of the disease, which hinders the development of effective treatments. Our recent understanding of the involvement of immune components in disease progression, prognostic or treatment stratification in other cancers revealed the significance of immuno-characterization of human malignancies [4, 5], which is lacking in OSCC. Our current TNM staging system for OSCC is informative for prognosis, however, it is likely that additional immuno-characterization of OSCC tumors in situ may further facilitate treatment stratification, especially for the new arrays of immune drugs for cancer [1].

Tumor infiltrating immune cells have been shown to provide prognostic values in several human malignancies [6,7,8,9,10]. For adaptive immune cells, CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes (CTLs) were generally considered as the main force against cancer. Both intra- and peri-tumoral CD8 expression have been shown to predict better survival in colorectal and esophageal cancers [11,12,13]. CD4+ cells consist of several subpopulations and its benefit was controversial [14,15,16,17]. Among these subpopulations, Th1 is considered as a critical component of tumor surveillance. T-bet is commonly used as a specific marker of Th1 cells, its expression have been shown significantly associated with survival of patients with breast or gastric cancer [18, 19]. As the important components of innate immunity, functions of macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells in tumor microenvironment draw much attention in recent decades [20,21,22]. CD68 has been widely used as a pan-macrophage marker, its expression was reported associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer and hepatocellular cancer [23, 24]. CD57 expression is most prominent in highly mature cytotoxic NK cells and terminally differentiated effector T-cells such as CTLs and Th cells [25]. NK cells were important effectors of both innate and adaptive immune response, their killing capacity against tumor cells enhances in absence of MHC class I molecules. Tumour CD57 expression has been reported independently predicting survival in patients with colorectal cancer, gastric cancer and prostate cancer [26,27,28].

Yet, the precise role of immune cells in OSCC remained poorly defined and controversial, though primary OSCC tumors are known to be heavily infiltrated with lymphocytes [29]. Thus, in this study several representative immune subsets (CD8, CD4, T-bet, CD68 and CD57) in a cohort of surgically treated OSCC patients were determined. To keep the consistency and reproducibility, the methodology recommended by an international breast cancer TILs Working Group was tested [30]. This study will provide new strategies to select the most promising immune markers for clinic trials through an integrative scope.

Methods

Study population

Our study randomly enrolled 78 OSCC patients who underwent curative operations at the Department of Oral-Maxillofacial Surgery, Stomatology Hospital Affiliated to Sun Yat-sen University, China, between 2007 and 2009. TNM staging was determined according to the Union for International Cancer Control 2002 standard (UICC2002). Pathological examination was performed by two independent pathologists according to the 2005 revised World Health Organization classification of OSCC tumors. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of Guanghua School of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University, China. Written informed consents had been obtained from all patients. The data were analyzed anonymously.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded specimens were cut into 4 μm thick sections. The slides were dewaxed by heating at 60 °C for 60 min followed by deparaffinizationin xylene and rehydration in graded alcohol. The slides were then put in Citrate Buffer solution (pH 6.0) and microwaved for 10 min at low power for antigen retrieval. Deparaffinized sections were stained with the following antibodies: CD8 1:150 (Abcam ab17147), CD4 1:250 (Abcam ab846), T-bet 1:100 (Abcam ab91109), CD68 1:100 (Dako M0814), CD57 1:150 (Abcam ab82749), Isotype Control (Abcam ab91353). The slides were then incubated in 3% H2O2 for 20 min for removal of endogenous peroxidase activity and subsequently incubated with secondary antibody (DAB) at 37 °C for 30 min. The tissue sections were immersed in a solution of 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Dako, Hamburg, Germany) and then counterstained with hematoxylin.

Microscopic evaluation of tumor sections

By use of a standard light microscope, images were acquired with a CCD-camera using a 20× objective, transferred to a PC and semi-automatically evaluated using the image analysis software COUNT (Biomas, Erlangen, Germany). Cases were scored blindly with respect to patient history, presentation, and previous scoring by two independent observers. In case of discrepancy, a final decision was made upon further re-examination of the slides in a microscope based on consensus by both pathologists.

Immune cells were identified by their specific markers (CD8, CD4, T-bet, CD68 and CD57). For each section, 10 areas of a representative field of tumor were assessed using an ocular grid comprising a high-power field (HPF) area of 0.0314 mm2. Tumor areas were divided into three anatomic compartments (i.e. tumor epithelial, tumor stroma and advancing tumor margin). The total number of each type of immune cells in tumor stroma, excluding cells within tumour cell nests, was counted. The average number of 10 HPFs was calculated as the final density of each section (cells per hpf).

Follow up

Phone interviews and physical examinations of each patient were carried out once every 6 months. Patients were followed till the closing date of the study or death, whichever reached first. Overall survival (OS) was determined based on the date of diagnosis until the date of death or the end of study. All patients were followed for more than two years, the median follow-up time was 48 months (ranged from 29 to 93 months).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and Stata/MP 14.0 software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Mean number of each type of immune cells was used as the cut off value separating patients into low and high infiltrated groups. Chi-square test was used to compare immune markers expression and clinicopathologic parameters. Overall survival (OS) was evaluated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the differences between survival curves were tested for statistical significance using the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the independent prognostic factors for OS. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) and area under curve (AUC) were used to evaluate and compare the prognostic value of immune cells. All tests were two-sided and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients outcome

The retrospectively registered cohort of 78 patients with OSCC who underwent a primary resection of tumor was investigated. Basic information and clinicopathological variables are summarized in Table 1. The average age of the patients was 60 years (range 24–82). The median follow up duration was 48 months (Inter-quartile range, 29–93 months). The panel consisted of about equal numbers of Stage I/II (n = 36, 46.15%) and Stage III/IV (n = 42, 53.85%) tumors. 48 (61.54%) patients were with lymphnode metastasis.

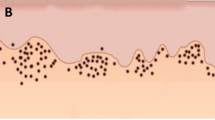

The distribution of CD8+, CD4+, T-bet+, CD68+ and CD57+ cells in OSCC tissues

Positively stained immune cells demonstrated brown granules on the membrane. The majority of immune cells were located in stroma compartment around cancer nests. Only a few were detected in the center of nests. The mean number of each cell type was shown in Table 2. CD8, CD4, T-bet, CD68 and CD57 expression in low and high infiltrated groups was shown in Fig. 1.

IHC analysis of immune cells distribution in OSCC tissues (200×). Immune cells were primarily distributed in tumor stroma. a–b: Representative images of IHC for evaluating low and high CD8 expression. c–d: CD4 expression; e–f: T-bet expression; g–h: CD68 expression; i–j: CD57 expression. a, c, e, g, i: Low expression; b, d, f, h, j: High expression

Relationships between clinicopathological features and density of immune cells

The relationships between clinicopathological features and density of immune cells were shown in Table 3. In the whole series, CD57 expression was associated with features of better prognosis including no lymphnode metastasis (p = 0.005), and early clinical stages (I/II vs III/IV, p = 0.016). Higher CD8 expression was significantly correlated with no lymphnode status (p = 0.033) and no drinking history (p = 0.014). T-bet was more abundant for patients older than 60 years (p = 0.046). CD4 and CD68 expression were not associated with any of the clinicopathological features in our OSCC cohort.

Assessment of survival by COX regression analysis

Univariate COX regression analyses and Kaplan-Meier survival curves

To determine the predictive value of immune cells infiltration, we performed the COX regression analysis. The results of the univariate COX regression analyses were summarized in Table 4.

Univariate analyses in all patients confirmed that both late clinical stage (p = 0.007) and lymph node metastasis (p < 0.001) were associated with a shorter survival. High CD8 and CD57 expression were significantly associated with longer survival (p < 0.001) in our cohort.

Figure 2a–c shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curves based on N stages and infiltration level (high and low defined by the average number) of CD8+ and CD57+ cells. Patients with lymphnode metastasis showed shorter survival compared with those without lymphnode involvement. The average OS of patients with different levels of immune cells were: 21.38 months in low and 43.68 months in high CD8 expression group; 22.14 months in low and 46.2 months in high CD57 expression group. Comparison of the Kaplan-Meier curves for OS indicated that higher CD8 and CD57 expression were associated with better patient survival. CD4, T-bet and CD68 levels did not show any correlation with patient outcome.

Correlation between immune cells infiltration and OS of OSCC patients. a, b and c Survival curves were stratified by CD8, CD57 and N stage with the Kaplan-Meier method. High CD8, high CD57 and no lymphnode metastasis were associated with longer survival (p < 0.001). d, e Kaplan-Meier curves illustrate the duration of survival according to the N stages and to the density of CD8+ cells (d) and CD57+ cells (e). CD8 and CD57 expression was associated with survival regardless of N stages (CD8-Lo/No LN metastasis vs. CD8-Hi/No LN metastasis, p < 0.001; CD8-Lo/ LN metastasis vs. CD8-Hi/ LN metastasis, p = 0.002; CD57-Lo/No LN metastasis vs. CD57-Hi/No LN metastasis, p < 0.001; CD57-Lo/ LN metastasis vs. CD57-Hi/ LN metastasis, p < 0.001). Hi, high expression; Lo, low expression; LN, lymphnode

We determined whether CD8 and CD57 could discriminate patient outcome at different N stages. Patients were stratified according to N stage (N0 and N1–3). As Fig. 2d and e showed, a strong stroma CD8 and CD57 expression correlated with favorable prognosis regardless of invasion of regional lymph nodes (p < 0.01).

Multivariate COX regression analysis.

The results of multivariate COX regression analysis confirmed that lymph node involvement (p = 0.008), CD8 expression (p = 0.03) and CD57 expression (p < 0.001) were significantly correlated with OS (Table 5). CD8 and CD57 expression can be considered as independent prognostic factors in OSCC patients. Clinical stage was not statistically significant in multivariate analysis.

Predictive accuracy for OS

To determine the predictive accuracy of immune cells on OS, we performed ROC curve analyses. As shown in Fig. 3 and Table 6, the respective predictive accuracy of CD8 and CD57 expression were all superior to TNM staging in determining patient outcome. CD57 provided the highest predictive accuracy (AUC = 0.868; 95% CI, 0.785–0.950).

Discussion

A comprehensive detection and assessment of factors influencing prognosis is important for improving patient management of OSCC. This study performed on various immune parameters in OSCC patients has shown that infiltration levels of immune cells were important predictive factors for patient outcome. Particularly, among these, stroma CD8 and CD57 expression were found to be the most powerful prognostic indicators.

We found that patients with strong CD8 expression had a significantly better clinical outcome. CD8+ cell is a crucial component of cell-mediated immunity as it produces interferon-γ upon interaction with tumour targets. In agreement to our findings, strong tumour infiltration by CD8+ cells has been correlated with a favorable outcome in several tumor types [31,32,33,34,35,36], including head and neck cancer [14,15,16,17, 37]. Former study on colorectal cancer with a large cohort has shown that infiltrating CD8+ T cells had a prognostic value that superior to and independent of those of TNM classification [38]. In our study, CD8 expression was significantly higher in patients with no lymph node involvements, when stratified patients according to N stages, CD8 expression was still correlated with favorable prognosis regardless of N stages, which revealed the superior prognostic value of CD8 expression.

Detailed analysis of CD57+ inflammatory cell activity in the host immune systems and head and neck cancer development has not been well defined. Function of tumor infiltrated CD57+cells remain unclear. Former studies have shown that CD57 was not an independent factor associated with survival [39, 40]. A more recent study included 57 cases of OSCC indicated that high level of CD57+ cells correlated with longer OS in OSCC patients and CD57 expression could be considered as a powerful indicator of OS [41]. This result was accordant with our study. In the present study, high CD57 expression was significantly associated with early clinical stage and no lymph node metastasis. A strong CD57 expression was found to be an independent prognostic factor for longer survival, moreover, it represented better predictive value compared with other immune cells, including CD4 and CD8 positive cells, and TNM staging. As researchers have reported positive correlation between presence of CD57+ T cells and cancer progression [25], our results indicated the potential important role of CD57+ NK cells in anti-tumor immunity against OSCC, which remained to be further confirmed by co-staining for CD3.

CD4+ cells serve a variety of biological functions according to their subpopulations. Th1 assist cytotoxic function of CD8+ cells, while Th2, Th17 and regulatory T cells (Tregs) could negatively regulate the adaptive immunity. T-bet plays critical roles in the differentiation of Th1 and regulates the Th1/Th2 shift. In OSCC, the role of CD4 remains controversial as mixed findings have been reported. Balermpas P et al. found no correlation between CD4 expression and clinical outcome of patients with head and neck cancer [15], whereas Nguyen N et al. reported that higher CD4 levels predicted improved OS and disease-specific survival [17]. T-bet has been shown to be associated with better outcome in patients with renal cell cancer, breast cancer, gastric cancer and colorectal cancer [19, 42,43,44,45]. We did not observe any correlation for either CD4 or T-bet expression and clinical outcome in our series. As CD4+ cells consist of various subpopulations, each of them could affect tumor behavior. The clinical significance according to each phenotype remains to be established.

Another important component of innate immunity, macrophages, is functionally differentiated into pro-inflammatory “M1” and alternative anti-inflammatory “M2” phenotypes. M1 type, commonly identified by staining the CD11c antigen, was conferred a significantly better prognosis. M2 type, expressing CD163 and MRC1, promoted tumor growth, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis [46]. Generally speaking, CD68 is the best established marker of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs), it is expressed on both M1 and M2 phenotypes. Ni YH et al. found that CD68+ TAMs infiltration in tumor stroma was correlated with high tumor grade and lymph node metastasis. More TAMs was correlated with short OS, but TAMs was not an independent predictive factor [46]. Our study showed that CD68 expression was not significantly associated with OSCC patient survival in both univariate and multivariate analysis, which was consistent with a more recent study including larger cohort of 278 patients by Nguyen N et al. [17] This result indicated the counterweight of M1 and M2 in tumor microenvironment of OSCC. Further study is required to differentiate M1 and M2 to determine their respective functions in OSCC.

In this study, special attention was paid for evaluating immune infiltrates. Regarding localization of the stained markers, stroma and tumor periphery not tumor nest were evaluated, because most current studies have shown that stroma immune cells were superior and more reproducible [47, 48]. We used full section over core biopsy (such as in the settings of tissue microarrays) because up till now, there was no published evidence that Tissue Microarrays (TMAs) can mirror or reflect the potential heterogeneity of immune cells in tumor, and the number and diameter of cores in TMAs vary, which will likely affect the accuracy needed for the determination of various immune components [30]. Regarding the scoring system, a quantitative parameter of cells count per HPF was applied. Machine scoring approaches, while promising, have not been published or validated yet, which needs to be explored in future studies.

There were some limitations in the current study. First was the limited size of our cohort with all patients being Chinese OSCC patients. It remains unclear if Chinese ethnic background is associated with particular immunological features. Second, a critical negatively regulated factor of immune response, Tregs, has not been separately stained. As a subpopulation of CD4+ cells, Tregs might contribute to the final negative results of association between CD4 and survival. Third, as CD68 expression cannot differentiate M1 and M2 subtypes of TAMs, further study should be designed including reliable markers of M1 and M2 TAMs for precise analysis. Fourth, without co-staining for CD3, the specific functions of CD57+ T cell and CD57+ NK cell in OSCC were not illuminated.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study revealed that stroma CD57 and CD8 expression were independent prognostic markers for OS of OSCC patients. When compared with TNM staging, expression of CD8 and CD57 provided superior predictive function. The results from this small OSCC cohort suggest that tumor infiltrating immune cells can potentially predict patient survival, thus provide new clues to therapeutic strategies in OSCC based on utilizing host immune response.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CTLs:

-

Cytotoxic lymphocytes

- HPF:

-

High-power field

- NK cells:

-

Natural killer cells

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- OSCC:

-

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- TAMs:

-

Tumor associated macrophages

- TMAs:

-

Tissue microarrays

- Tregs:

-

Regulatory T cells

References

Winck FV, Prado RAC, Ramos DR, et al. Insights into immune responses in oral cancer through proteomic analysis of saliva and salivary extracellular vesicles. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16305.

Carvalho AL, Nishimoto IN, Califano JA, Kowalski LP. Trends in incidence and prognosis for head and neck cancer in the United States: a site-specific analysis of the SEER database. Int J Cancer. 2005;114(5):806–16.

van der Waal I. Are we able to reduce the mortality and morbidity of oral cancer; some considerations. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18(1):e33–7.

Ujiie H, Kadota K, Nitadori JI, et al. The tumoral and stromal immune microenvironment in malignant pleural mesothelioma: a comprehensive analysis reveals prognostic immune markers. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(6):e1009285.

Punt S, van Vliet ME, Spaans VM, et al. FoxP3(+) and IL-17(+) cells are correlated with improved prognosis in cervical adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64(6):745–53.

Lee AM, Clear AJ, Calaminici M, et al. Number of CD4+ cells and location of forkhead box protein P3-positive cells in diagnostic follicular lymphoma tissue microarrays correlates with outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(31):5052–9.

Englund E, Reitsma B, King BC, et al. The human complement inhibitor sushi domain-containing protein 4 (SUSD4) expression in tumor cells and infiltrating T cells is associated with better prognosis of breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:737.

Chirica M, Le BL, Lehmann-Che J, et al. Phenotypic analysis of T cells infiltrating colon cancers: correlations with oncogenetic status. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(8):e1016698.

Jia Q, Zhou J, Chen G, et al. Diversity index of mucosal resident T lymphocyte repertoire predicts clinical prognosis in gastric cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(4):e1001230.

Zelba H, Weide B, Martens A, Bailur JK, Garbe C, Pawelec G. The prognostic impact of specific CD4 T-cell responses is critically dependent on the target antigen in melanoma. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(1):e955683.

Naito Y, Saito K, Shiiba K, et al. CD8+ T cells infiltrated within cancer cell nests as a prognostic factor in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58(16):3491–4.

Funada Y, Noguchi T, Kikuchi R, Takeno S, Uchida Y, Gabbert HE. Prognostic significance of CD8+ T cell and macrophage peritumoral infiltration in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2003;10(2):309–13.

Schumacher K, Haensch W, Roefzaad C, Schlag PM. Prognostic significance of activated CD8(+) T cell infiltrations within esophageal carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2001;61(10):3932–6.

Watanabe Y, Katou F, Ohtani H, Nakayama T, Yoshie O, Hashimoto K. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, particularly the balance between CD8(+) T cells and CCR4(+) regulatory T cells, affect the survival of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109(5):744–52.

Balermpas P, Michel Y, Wagenblast J, et al. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes predict response to definitive chemoradiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(2):501–9.

Nordfors C, Grün N, Tertipis N, et al. CD8+ and CD4+ tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in relation to human papillomavirus status and clinical outcome in tonsillar and base of tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(11):2522–30.

Nguyen N, Bellile E, Thomas D, et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and survival in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2016;38(7):1074–84.

Ladoire S, Arnould L, Mignot G, et al. T-bet expression in intratumoral lymphoid structures after neoadjuvant trastuzumab plus docetaxel for HER2-overexpressing breast carcinoma predicts survival. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(3):366–71.

Chen LJ, Zheng X, Shen YP, et al. Higher numbers of T-bet(+) intratumoral lymphoid cells correlate with better survival in gastric cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(3):553–61.

Lima L, Oliveira D, Tavares A, et al. The predominance of M2-polarized macrophages in the stroma of low-hypoxic bladder tumors is associated with BCG immunotherapy failure. Urol Oncol. 2014;32(4):449–57.

Focosi D, Petrini M. CD57 expression on lymphoma microenvironment as a new prognostic marker related to immune dysfunction. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(10):1289–91. author reply 1291-2

Greaves P, Clear A, Coutinho R, et al. Expression of FOXP3, CD68, and CD20 at diagnosis in the microenvironment of classical Hodgkin lymphoma is predictive of outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(2):256–62.

Medrek C, Pontén F, Jirström K, Leandersson K. The presence of tumor associated macrophages in tumor stroma as a prognostic marker for breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:306.

Zhou J, Ding T, Pan W, Zhu LY, Li L, Zheng L. Increased intratumoral regulatory T cells are related to intratumoral macrophages and poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(7):1640–8.

Kared H, Martelli S, Ng TP, Pender SL, Larbi A. CD57 in human natural killer cells and T-lymphocytes. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65(4):441–52.

Chaput N, Svrcek M, Auperin A, et al. Tumour-infiltrating CD68+ and CD57+ cells predict patient outcome in stage II-III colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(4):1013–22.

Ishigami S, Natsugoe S, Tokuda K, et al. Prognostic value of intratumoral natural killer cells in gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88(3):577–83.

Wangerin H, Kristiansen G, 0000–0003–4149-5487 AO, et al. CD57 expression in incidental, clinically manifest, and metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Biomed Res Int. 2014. 2014: 356427.

Huang TY, Hsu LP, Wen YH, et al. Predictors of locoregional recurrence in early stage oral cavity cancer with free surgical margins. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(1):49–55.

Salgado R, Denkert C, Demaria S, et al. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: recommendations by an international TILs working group 2014. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(2):259–71.

Matsumoto H, Thike AA, Li H, et al. Increased CD4 and CD8-positive T cell infiltrate signifies good prognosis in a subset of triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;156(2):237–47.

Liu L, Zhao G, Wu W, et al. Low intratumoral regulatory T cells and high peritumoral CD8(+) T cells relate to long-term survival in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma after pancreatectomy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65(1):73–82.

Geng Y, Shao Y, He W, et al. Prognostic role of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37(4):1560–71.

Nedergaard BS, Ladekarl M, Thomsen HF, Nyengaard JR, Nielsen K. Low density of CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ cells is associated with increased risk of relapse in squamous cell cervical cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(8):1135–8.

Wang K, Xu J, Zhang T, Xue D. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer predict the response to chemotherapy and survival outcome: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016; DOI: 10.18632/oncotarget. 9988.

Mao Y, Qu Q, Chen X, Huang O, Wu J, Shen K. The prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer: a systematic Review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152500.

Balermpas P, Rödel F, Rödel C, et al. CD8+ tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in relation to HPV status and clinical outcome in patients with head and neck cancer after postoperative chemoradiotherapy: a multicentre study of the German cancer consortium radiation oncology group (DKTK-ROG). Int J Cancer. 2016;138(1):171–81.

Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science (80- ). 2006. 313(5795): 1960–4.

Zancope E, Costa NL, Junqueira-Kipnis AP, et al. Differential infiltration of CD8+ and NK cells in lip and oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39(2):162–7.

Fraga CA, de Oliveira MV, Domingos PL, et al. Infiltrating CD57+ inflammatory cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: clinicopathological analysis and prognostic significance. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2012;20(3):285–90.

Taghavi N, Bagheri S, Akbarzadeh A. Prognostic implication of CD57, CD16, and TGF-beta expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2015;45(1):58–62.

Yu H, Yang J, Jiao S, Li Y, Zhang W, Wang J. T-box transcription factor 21 expression in breast cancer and its relationship with prognosis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(10):6906–13.

Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, et al. Clinical impact of different classes of infiltrating T cytotoxic and helper cells (Th1, th2, treg, th17) in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71(4):1263–71.

Hennequin A, Derangère V, Boidot R, et al. Tumor infiltration by Tbet+ effector T cells and CD20+ B cells is associated with survival in gastric cancer patients. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(2):e1054598.

Dielmann A, Letsch A, Nonnenmacher A, Miller K, Keilholz U, Busse A. Favorable prognostic influence of T-box transcription factor Eomesodermin in metastatic renal cell cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65(2):181–92.

Ni YH, Ding L, Huang XF, Dong YC, Hu QG, Hou YY. Microlocalization of CD68 tumor-associated macrophages in tumor stroma correlated with poor clinical outcomes in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(7):5291–8.

Kayser G, Schulte-Uentrop L, Sienel W, et al. Stromal CD4/CD25 positive T-cells are a strong and independent prognostic factor in non-small cell lung cancer patients, especially with adenocarcinomas. Lung Cancer. 2012;76(3):445–51.

Goc J, Germain C, Vo-Bourgais TK, et al. Dendritic cells in tumor-associated tertiary lymphoid structures signal a Th1 cytotoxic immune contexture and license the positive prognostic value of infiltrating CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res. 2014;74(3):705–15.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This project was supported by Nonprofit Industry Research Specific Fund of National Health and Family Planning Commission of China (No. 201502018), the National Natural Science Foundations of China (No. 81472524, 81,630,025, 81,500,864 and 81,602,383), Research Grant Council, Hong Kong (No.17114814, General Research Fund). The funding agency has no role in the actual experimental design, analysis, or writing of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Due to ethical restrictions, the raw data underlying this paper are available upon request to the corresponding author. Other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors’ contributions

JF, XXL, DM, XQL and YCC were involved in patients enrollment, collection of clinicopathological data and tissue samples; JF, XXL, YW and DM were involved in the immunohistochemistry experiments and microscopic evaluation of tumor sections; XXL, YCC, JX and YW were involved in the clinical follow-up of the patients; JF and XQL were involved in statistical analysis; JF, XXL, VL, ZW and BC were involved in the interpretation of the results. XXL, JF, VL, DM, XQL, YCC, YW, JX, ZW and BC were involved in the manuscript drafting or editing. ZW and BC were involved in the conception and design of the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Guanghua School of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University, China (approval number: ERC-[2006]-04, ERC-[2011]-14). All patients have provided written informed consent for their information to be stored and used in the hospital database.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, J., Li, X., Ma, D. et al. Prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating immune cells in oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 17, 375 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3317-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3317-2