Abstract

Background

After the approval of pazopanib for the treatment of soft tissue sarcoma (STS), pneumothorax was reported as an unexpected adverse event during pazopanib treatment. The incidence and risk factors of pneumothorax during pazopanib treatment for STSs have not been established yet.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the cases of all of the STS patients treated with pazopanib between November 2012 and December 2014 at our institute and evaluated the prevalence, incidence, treatment details and risk factors for pneumothorax in the STS patients during pazopanib treatment.

Results

A total of 58 patients were enrolled; 45 of them had lung and/or pleural lesions at the start of pazopanib treatment. During the median follow-up time of 219 days (range 23–659), 13 pneumothorax events occurred in six patients; the prevalence and incidence of pneumothorax were 10.3 % and 0.56 per treatment-year, respectively. The median onset of pneumothorax was day 115 (range 6–311). No patients died of pneumothorax, but pazopanib was interrupted in 10 events and chest drainage was performed in eight events. Pazopanib continuation or restart after the recovery from pneumothorax was conducted after 9 of the 13 events. The median progression-free survival of patients with and without pneumothorax events were 144 and 128 days (p = 0.89) and the median overall survival periods were 293 and 285 days (p = 0.69), respectively. By logistic regression analyses, the maximum diameter of the lung metastases ≥ 30 mm (OR 13.3, 95 % CI 1.1–155.4, p = 0.039) and a history of pneumothorax before the pazopanib induction (OR 16.6, 95 % CI 1.1–256.1, p = 0.045) were significantly predictive of pneumothorax.

Conclusions

In our retrospective analysis, pneumothorax was observed in 10.3 % of 58 STS patients during pazopanib treatment. The diameter of the lung metastases and a history of pneumothorax could be useful for evaluating the risk of pneumothorax in pazopanib treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Soft tissue sarcomas (STSs) are heterogeneous malignant diseases, originating from mesenchymal tissues all over the body. Approximately 30 % of all STS patients have some metastatic lesions, and the prognoses of metastatic STS patients are still poor [1–3]. There have been some case reports of pneumothorax as a complication in STS patients with lung metastases; due to the rarity of the event, however, information about the prevalence and the risk factors of pneumothorax in STS patients has been limited [4].

In 2012, pazopanib, a multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor, was approved for the treatment of STS patients based on the evidence obtained in a phase 3 clinical trial, in which pazopanib was shown to improve the prognoses of advanced STS patients [4]. However, throughout the more than 2 years after pazopanib’s approval, pneumothorax has been reported as an unexpected adverse event in STS patients [5, 6]. Though the relation between pneumothorax and pazopanib treatment is not clear, once pneumothorax occurs, in most cases pazopanib treatment would have to be interrupted. For the safe management of pazopanib treatment, it is necessary to evaluate the prevalence, the incidence and the risk factors for pneumothorax in STS patients during pazopanib treatment. Here we investigated the details of pneumothorax events observed in STS patients during pazopanib treatment.

Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Cancer Institute Hospital of Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research. After the approval of the institutional review board, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of STS patients treated with pazopanib at our institute between November 2012 and December 2014. We determined the prevalence, the incidence, the severity and the managements of pneumothorax during these patients’ pazopanib treatment. The prevalence of pneumothorax was calculated as the percentage of patients suffering from pneumothorax. The incidence of pneumothorax was calculated as the number of pneumothorax episodes per treatment-year. The severities of pneumothorax events were evaluated by grading based on the U.S. National Center Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 4.0).

We also reviewed the baseline characteristics of all of the STS patients enrolled in the study and evaluated the clinical risk factors of pneumothorax by comparing the characteristics of the patients with and without pneumothorax events. We performed univariate and the multivariable analyses to evaluate the association between each risk factor and pneumothorax using Fisher’s extract test and a logistic regression test, respectively.

For the evaluation of prognoses, the progression-free survival (PFS) and the overall survival (OS) from the date of pazopanib induction were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The PFS and the OS of the patients with and without pneumothorax events were compared by the log-rank test.

The patients’ objective responses were also evaluated and compared. The objective response and the disease progression were defined based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. Independent of the objective response, cavitations of lung lesions during pazopanib treatment were also evaluated.

In all analyses, the p-values were two-sided and considered significant when <0.05.

Results

A total of 58 STS patients had been treated with pazopanib at our institute between November 2012 and December 2014, and the median follow-up time from the start of pazopanib treatment was 219 days (range 23–659 days). At the time of our analyses, 43 patients were certified as showing disease progression and 30 patients had died due to their STS.

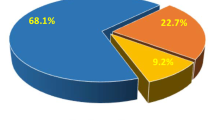

The patients’ characteristics at baseline are shown in Table 1. In Japan, pazopanib is also approved for liposarcoma treatment, and we thus included nine liposarcoma patients in the study. Lung and/or pleural lesions were present at baseline in 45 patients (78 %); lung lesions were present in 41 (71 %) patients, and pleural lesions were present in 23 (40 %) patients. Twenty (34 %) patients had smoking histories; details of smoking index (the number of cigarette-years) were as follows; median 238, range (64–1170), and smoking index was 400 or more in 6 patients.

The prevalence, incidence and management of pneumothorax

Throughout the follow-up period, 13 pneumothorax events were observed in six of the 58 STS patients enrolled in the analysis; the prevalence of pneumothorax was 10.3 %. The median pazopanib treatment period was 115 days (range 5–659 days), and the incidence of pneumothorax was 0.56 per treatment-year. The median onset of pneumothorax events was at 115 days of pazopanib treatment. All patients with pneumothorax events had lung and/or pleural lesions at the start of pazopanib.

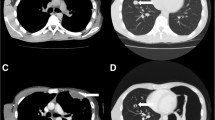

The details of pneumothorax events are shown in Table 2. Based on the CTCAE, 7 of the 13 pneumothorax events were evaluated as grade 3, and in two events pneumothorax occurred bilaterally (Fig. 1). Recurrences of pneumothorax events were observed in three patients. In Patient 3, a 27-year-old male with undifferentiated sarcoma, not otherwise specified (NOS), pneumothorax events occurred five times during pazopanib treatment. No patients died of pneumothorax, but pazopanib treatment was interrupted in 10 events and the chest drainage was performed in eight events. Pazopanib continuation or restart after the recovery from pneumothorax was conducted after nine events. The clinical courses of the six patients with pneumothorax are summarized in Fig. 2.

Risk factors of pneumothorax

In our univariate analysis of baseline characteristics of the STS patients treated with pazopanib, the pathological diagnosis of synovial sarcoma, the presence of lung lesions with ≥ 30 mm dia. and the presence of histories of pneumothorax were significant (Table 3). Of these, the multivariable analysis revealed that the maximum diameter of the lung metastases ≥ 30 mm (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 13.3, 95 % confidence interval [CI] = 1.1–155.4, p = 0.039) and the presence of a history of pneumothorax before the pazopanib induction (adjusted OR 16.6, 95 % CI 1.1–256.1, p = 0.045) were also significantly predictive of pneumothorax (Table 4).

Prognoses and responses to pazopanib in STS patients with and without pneumothorax

The median PFS and OS of all STS patients treated with pazopanib were 130 days (95 % CI 112–148) and 285 days (95 % CI 256–313). The comparison of prognoses between the patients with and without pneumothorax by log-rank test showed that the median PFS of the patients with and without pneumothorax were 144 and 128 days (p = 0.89) and the median OS values were 293 and 285 days (p = 0.69), respectively (Fig. 3). There were no significant differences in PFS or OS due to the presence of pneumothorax events. Prognostic factors other than the presence of pneumothorax were also evaluated by the log-rank test, but there were no statistically significant factors (Table 5).

As for the objective responses, a partial response (PR) was observed in 5 of the 58 STS patients (the response rate was 8.6 %); there were no PRs in the patients with pneumothorax (based on the RECIST criteria). Cavitations of lung lesions were observed in four patients, and two of them had pneumothorax during pazopanib treatment (Patient No. 1 and No. 3).

Discussion

The lung is the major organ in which STS metastases are most often observed; 22 % of all STS patients have lung metastases [7]. Though there have been many case reports of STS patients with pneumothorax, the prevalence and the risk factors of pneumothorax in STS patients have not yet been established.

Hoag et al. reviewed case reports of pneumothorax in STS patients and estimated that the prevalence of pneumothorax in STS patients is 1.9 % [8]. this prevalence is higher than those of patients with primary lung cancers, which was estimated as 0.32 % in Lai’s retrospective analysis [9].

During pazopanib treatment, the prevalence of pneumothorax in STS patients might be higher. In 2014, we preliminarily reported the prevalence of pneumothorax in 32 STS patients treated by pazopanib as 9.4 % [5], and in the present study the prevalence of pneumothorax among 58 STS patients was 10.5 %. Similar to our results, Verschoor et al. reported case series of pneumothorax in STS patients treated by pazopanib; 6 of 43 patients experienced pneumothorax in their study (14.0 %) [6]. In our present study, the prevalence of pneumothorax was even higher than those in prospective clinical trials or multicenter analyses of pazopanib-treated STS patients. In the Palette study, a multicenter phase III trial of pazopanib treatment for STS patients, the prevalence of pneumothorax was 3 % (8 of 246 patients) [4]. In the post-marketing surveillance of pazopanib in Japan, pneumothorax was observed in 23 of 539 patients who received pazopanib (4.3 %), and 12 patients (2.2 %) were diagnosed as grade 3 or more [10].

At our institute, pneumothorax events occurred soon after the approval of pazopanib, and since then chest radiographs have been performed once or twice monthly during pazopanib treatment in clinical practice. This frequent evaluation by chest radiographs helps identify low-grade pneumothorax without clinically relevant symptoms, and it might be the reason for the high prevalence of pneumothorax in our present analysis; in fact, if we exclude the patients with only low-grade pneumothorax (Patient Nos. 1, 5 and 6), the prevalence of severe pneumothorax at our institute was 3 of 58 patients (5.2 %). This result is similar to the prevalence of pneumothorax in the Palette study.

Pazopanib is considered an antiangiogenic agent since it targets the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) [4]. Antiangiogenic agents are known to cause cavitations of lung lesions [11, 12]. It has been suggested that tumor cavitations during or after chemotherapy might be signs of the clinical response, but also that they could be risk factors for pneumothorax [13]. Our present population included patients in whom cavitations of lung lesions developed during pazopanib treatment, especially among the patients with pneumothorax events. In STS patients, however, cavitations of lung lesions have also occurred during chemotherapies using cytotoxic agents, and it is thought that the necrosis of pulmonary or pleural lesions in response to chemotherapy by cytotoxic agents could be responsible for pneumothorax [8, 14]. Moreover, in the prospective clinical trials of pazopanib treatment for malignancies other than STS, such as renal cell carcinomas and ovarian cancers, pneumothorax was more rarely reported as an adverse event [15, 16]. As for STS patients, the nature of the disease could be more closely related to risk factors of pneumothorax than are the treatment drugs.

In our current analysis, the clinical features of maximum lesion size and number of lung lesions were significant predictors of pneumothorax in the multivariable analysis. However, our analysis was retrospective study, and, due to the small sample size and few numbers of events, the range of adjusted odd ratios were broad (Table 4). These are the limitations of our study, and the re-analyses of bigger sample size, prospective cohorts will be necessary for the certification of risk factors of pneumothorax. In other studies, good performance status and a normal hemoglobin level were suggested to be advantageous for long-term outcomes, and older age was suggested to be associated with liver toxicity [17, 18]. By updating STS patients’ clinical information and analyses, it could be possible to estimate the risk of pneumothorax more precisely in the future.

Conclusion

Pneumothorax was observed in 10.3 % of 58 STS patients during pazopanib treatment. By the multivariable analyses, the diameter of the lung metastases and a history of pneumothorax could be useful for evaluating the risk of pneumothorax in pazopanib treatment.

Abbreviations

- NOS:

-

Not otherwise specified

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PR:

-

Partial response

- STS:

-

Soft tissue sarcoma

- VEGFR:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

References

A Snapshot of Sarcoma - National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/research/progress/snapshots/sarcoma. Accessed 5 Nov 2014.

Chen C, Borker R, Ewing J, Tseng WY, Hackshaw MD, Saravanan S, Dhanda R, Nadler E. Epidemiology, treatment patterns, and outcomes of metastatic soft tissue sarcoma in a community-based oncology network. Sarcoma 2014; Article ID 145764.

Clark MA, Fisher C, Judson I, Thomas JM. Soft-tissue sarcomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:701–11.

Van der Graaf WT, Blay JY, Chawla SP, Kim DW, Bui-Nguyen B, Casali PG, Schöffski P, Aglietta M, Staddon AP, Beppu Y, Le Cesne A, Gelderblom H, Judson IR, Araki N, Ouali M, Marreaud S, Hodge R, Dewji MR, Coens C, Demetri GD, Fletcher CD, Dei Tos AP, Hohenberger P. EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group: Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1879–86.

Nakano K, Inagaki L, Tomomatsu J, Motoi N, Gokita T, Ae K, Tanizawa T, Shimoji T, Matsumoto S, Takahashi S. Incidence of pneumothorax in advanced and/or metastatic soft tissue sarcoma patients during pazopanib treatment. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2014;26:357.

Verschoor AJ, Gelderblom H. Pneumothorax as adverse event in patients with lung metastases of soft tissue sarcoma treated with pazopanib: a single reference centre case series. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2014;4:14.

Billingsley KG, Burt ME, Jara E, Ginsberg RJ, Woodruff JM, Leung DHY, Brennan MF. Pulmonary metastases from soft tissue sarcoma: analysis of patterns of disease and postmetastasis survival. Ann Surgery. 1999;229:602–12.

Hoag JB, Sherman M, Fasihudin Q, Lund ME. A comprehensive review of spontaneous pneumothorax complicating sarcoma. CHEST. 2010;138:510–8.

Lai RS, Perng RP, Chang SC. Primary lung cancer complicated with pneumothorax. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1992;22:194–7.

Kawai A, Araki N, Ando Y, Nakano K, Machida M, Yoshida P. Post marketing surveillance (PMS) in Japan for soft tissue sarcoma (STS) patients treated with pazopanib. Eur. J. Cancer. 2015;51(Suppl 3):S701.

Crabb SJ, Patsios D, Sauerbrei E, Ellis PM, Arnold A, Goss G, Leight NB, Shepherd FA, Powers J, Seymour L, Laurie SA. Tumor Cavitation: Impact on objective response evaluation in trials of angiogenesis inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:404–10.

Marom EM, Martinez CH MD, Truong MT, Lei X, Sabloff BS, Munden RF, Gladish GW, Herbst RS MD, Morice RC, Stewart DJ, Jimenez CA, Blumenschein GR, Onn A. Tumor cavitation during therapy with antiangiogenesis agents in patients with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:351–7.

Interiano RB, McCarville MB, Wu J, Davidoff AM, Sandoval J, Navid F. Pneumothorax as a complication of combination antiangiogenic therapy in children and young adults with refractory/recurrent solid tumors. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(9):1484–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.01.005.

Fiorelli A, Vicidomini G, Napolitano F, Santini M. Spontaneous pneumothorax after chemotherapy for sarcoma with lung metastases: Case report and consideration of pathogenesis. J Thorac Dis. 2011;3:138–40.

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, Reeves J, Hawkins R, Guo J, Nathan P, Staehler M, de Souza P, Merchan JR, Boleti E, Fife K, Jin J, Jones R, Uemura H, Giorgi UD, Harmenberg U, Wang J, Sternberg CN, Deen K, McCann L, Hackshaw MD, Crescenzo R, Pandite LN, Choueiri TK. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:722–31.

du Bois A, Floquet A, Kim JW, Rau J, del Campo JM, Friedlander M, Pignata S, Fujiwara K, Vergote I, Colombo N, Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Kimmig R, Ray-Coquard I, Zang R, Diaz-Padilla I, Baumann KH, Mouret-Reynier MA, Kim JH, Kurzeder C, Lesoin A, Vasey P, Marth C, Canzler U, Scambia G, Shimada M, Calvert P, Pujade-Lauraine E, Kim EBG, Herzog TJ, Mitrica I, Schade-Brittinger C, Wang Q, Crescenzo R, Harter P. Incorporation of pazopanib in maintenance therapy of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3374–82.

Kasper B, Sleijfer S, Litière S, Marreaud S, Verweij J, Hodge RA, Bauer S, Kerst JM, van der Graaf WTA. Long-term responders and survivors on pazopanib for advanced soft tissue sarcomas: subanalysis of two European organisations for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) clinical trials 62043 and 62072. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:719–24.

Powles T, Bracarda S, Chen M, Norry E, Compton N, Heise M, Hutson T, Harter P, Carpenter C, Pandite L, Kaplowitz N. Characterisation of liver chemistry abnormalities associated with pazopanib monotherapy: A systemic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials in advanced cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1293–302.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff members at the Departments of Medical Oncology, Orthopedic Surgery, Gastrointestinal Surgery, Gynecology, and Urology at the Cancer Institute Hospital of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research for introducing and treating the patients enrolled in this study.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant materials are provided in the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design: KN; Manuscript writing: KN; Final approval: KN, NM, JT, TG, KA, TT, SM, ST; Pathological review; NM, Patients’ management; KN, JT, TG, KA, TT, SM, ST; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

Kenji Nakano has been a participant in GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis advisory boards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Cancer Institute Hospital of Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakano, K., Motoi, N., Tomomatsu, J. et al. Risk factors for pneumothorax in advanced and/or metastatic soft tissue sarcoma patients during pazopanib treatment: a single-institute analysis. BMC Cancer 16, 750 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2786-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2786-z