Abstract

Background

Despite the high rates and regional variation of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) in East Africa, the contributions of smoking and alcohol to the ESCC burden in the general population are unknown.

Methods

We conducted a case-control study of patients presenting for upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examination at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital, Uganda. Sociodemographic data including smoking and alcohol intake were collected prior to endoscopy. Cases were those with histological diagnosis of ESCC and controls were participants with normal endoscopic examination and gastritis/duodentitis or normal histology. We used odds ratios associated with ESCC risk to determine the population attributable fractions for smoking, alcohol use, and a combination of smoking and alcohol use among adults aged 30 years or greater who underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Results

Our study consisted of 67 cases and 142 controls. Median age was 51 years (IQR 40–64); and participants were predominantly male (59 %). Dysphagia and/or odynophagia as indications for endoscopy were significantly more in cases compared to controls (72 % vs 6 %, p < 0.0001). Male gender and increasing age were statistically associated with ESCC. In the unadjusted models, the population attributable fraction of ESCC due to male gender was 55 %, female gender - 49 %, smoking 20 %, alcohol 9 % and a combination of alcohol & smoking 15 %. After adjusting for gender and age, the population attributable fraction of ESCC due to smoking, alcohol intake and a combination of alcohol & smoking were 16, 10, and 13 % respectively.

Conclusion

In this population, 13 % of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cases would be avoided if smoking and alcohol use were discontinued. These results suggest that other important risk factors for ESCC in southwestern Uganda remain unknown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is lethal, with a poor 5-year survival even in resource rich settings [1, 2]. In sub-Saharan Africa, the incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) has regional variation with southern and eastern regions reporting significantly higher incidence rates [3]. It is postulated that differences in risk factor profiles may explain these regional variations. Therefore, public health approaches for risk factor modification and early screening methods for curable lesions offer a great opportunity to reduce ESCC morbidity and mortality.

Though alcohol use and smoking are known risk factors for ESCC [4], existing data are inconclusive in linking various factors to an increased risk of ESCC including: human papilloma virus [5, 6], consumption of hot drinks [7], diets low in fruit and vegetables [8], and exposure to nitrosamines [9, 10], suggesting that these environmental risk factors alone may not be responsible for ESCC.

Though alcohol and tobacco are thought to synergistically interact for the development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [11], data are lacking in the characterizations of the impact of these risk factors on the incidence of ESCC using population attributable fractions (PAFs). PAFs account both for the strength of the association and the prevalence of the risk factor. Studies in ESCC among low and high risk populations report between 60 and 75 % population attributable fractions for ESCC due to smoking and alcohol [12–15] but PAFs for Africa have not been previously reported. We aimed to determine the population attributable fraction for smoking and alcohol use for ESCC risk in an ESCC high incidence African population in southwestern Uganda.

Methods

Study participants and procedures

We carried out a case control study using data from all patients, aged 30 years or greater, who presented for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy from January 2003 to December 2014 at the Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH), southwestern Uganda. Our endoscopy service was nonfunctional during 2010 to 2012. However, our center is the only endoscopy service in southwestern Uganda; receiving referrals from within MRRH and other health facilities; private and public in southwestern Uganda with an estimated population of 8.7 million people [16].

Before performing upper GI endoscopy, a trained nurse administered a standardized questionnaire to collect data including age, gender, history of alcohol and smoking, and symptoms after provision of informed consent for endoscopy & biopsy.

A nurse sprayed 5 mL of 1 % lidocaine into the patients’ mouth for 5 min; intravenous medications diazepam 5 mg and fentanyl 50 μg were then administered for sedation. With the patients positioned in the left lateral position, a trained endoscopist then inserted a gastroscope visually examining the entire esophagus and stomach. Tissue biopsies of both abnormal and occasionally normal mucosae were picked from unstained foci with the number of biopsies taken depended on the size of the lesion but minimum of three biopsies. Some pieces of tissue biopsy were used to perform rapid urease (CLO) test while the remaining biopsies were kept in 10 % buffered formalin before transportation to the histopathology laboratory at the department of Pathology, Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST) for histopathology microscopic examination.

At the MUST histopathology laboratory, all esophageal biopsies were processed into sections, stained with hematoxylin and eosin for 1 h, and then examined using standard diagnostic criteria for microscopic atypia. Specifically, for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, pathologist reported features such as presence of nuclear atypia, prominent keratinization and evidence of invasion [17].

Data collection

We reviewed participants’ records, first extracting cases of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and then consecutively sampling for controls. For all participants, we collected pre-endoscopic data including age, sex, history of alcohol and smoking, and presenting symptoms. We also reviewed diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy reports to collect information pertaining to the site of suspicious esophageal lesions i.e., upper third (15–24 cm), middle third (24–32 cm), and lower third (32–40 cm) esophageal lesions [18]. All data were doubly entered into an electronic database and crosschecked to minimize entry and transcription errors.

Ascertainment of cases and controls

We defined a case as any participant having histological diagnosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma either differentiated or undifferentiated. Controls were participants with normal endoscopic examination or gastritis/duodentitis or normal histology. We excluded from this analysis participants with histological diagnoses of other esophageal abnormalities such as esophageal dysplasia, esophageal hyperplasia, esophagitis, esophageal adenocarcinoma, Barrett’s esophagus or gastric cancer, peptic ulcer disease or missing histology results.

Statistical analysis

We described baseline characteristics of cases and controls using summary statistics.

Associations between exposure variables: sex, age at presentation, history of smoking and alcohol with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma were estimated in unadjusted and multivariate logistic regression models expressed as odds ratios with 95 % confidence intervals. Exposure variables smoking and drinking alcohol were treated as binary (never, reference group; ever, risk group). Only variables that provided odds ratios (ORs) for ESCC with p-values < 0.1 in the univariate logistic regression model were included in the multivariate logistic regression model.

Because the main objective of this analysis was to investigate the population attributable fraction of Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma due to smoking and alcohol, we assumed that smoking and drinking alcohol individually exert effects on ESCC risk and that these interact thus, we introduced a joint category of smoking and alcohol using an interaction term [19]. We used crude odds ratio estimates from the univariate logistic regression and the adjusted odds ratios controlling for gender and age to determine the unadjusted and adjusted population attributable fractions (PAF) for smoking, alcohol use, and a combination of smoking and alcohol use. We used crude odds ratio estimates from the univariate logistic regression and the adjusted odds ratios controlling for gender and age to determine the unadjusted and adjusted population attributable fractions (PAF) for smoking, alcohol use, and a combination of smoking and alcohol use respectively. This was calculated using the punafcc package available in STATA software. The PAFs and 95 % confidence intervals were estimated by a method that is based on unconditional logistic regression [20], which provides adjusted PAF estimates by combining adjusted odds ratio estimates and the observed prevalence of the risk factors among case patients.

All statistical tests were two-sided. All analyses were performed with STATA version 13 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

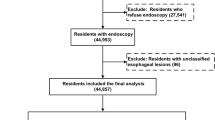

Among 913 endoscopes performed at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital between 2003 and 2014, there were 67 (7.34 %) new cases of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. We excluded 428 (46.88 %) with missing histology results, 53 (5.81 %) with inadequate biopsies (no histological diagnosis could be made), and 148 with other histology results of esophagitis, esophageal adenocarcinoma, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal Kaposi sarcoma, and gastric malignancies.

Among the 142 controls, 30 (21.13 %) had normal histology and 45 (31.69 %) had gastritis/duodentitis. There were a higher proportion of males among cases compared to controls (79.10 % vs 52.82 %). The age distribution was similar among cases and controls except for < 41 years with a higher proportion of controls (Table 1).

As expected, indication for endoscopy were significantly different between cases and controls, for example, dysphagia and/or odynophagia were significantly more frequent endoscopic indications in cases compared to controls (72.29 % vs 5.56 %, p < 0.0001) (Table 2). Overall, the common sites for esophageal masses were the lower and mid portions of the esophagus in 28 (41.79 %) and 21 (31.34 %) respectively. Self-reported HIV infection rates were similar between these groups.

In the univariate logistic regression modeling, we found; increasing age, male gender, alcohol & smoking as factors associated with a diagnosis of ESCC. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3), we found male gender (AOR 3.65, 95 % CI (1.67 – 7.98), p = 0.001), age group of 41 to 50 years (AOR 12.95, 95 % CI (2.57 – 65.10), p = 0.002); 51 – 60 year (AOR 6.50, 95 % CI (1.32 – 31.90), p = 0.021); 61 – 70 year (AOR 7.26, 95 % CI (1.45 – 36.41), p = 0.016); and age > 70 year (AOR 5.23, 95 % CI (0.99 – 27.69), p = 0.052) were independently correlated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Self-reported use of alcohol and smoking were not statistically associated with ESCC (Table 3).

To estimate the population attributable fraction of ESCC due to smoking and alcohol, age data was used as continuous (modeling decision taken based on the -2Log likelihood). In the unadjusted models, the population attributable fraction of ESCC due to male gender was 55.36 %, 95 % CI (26.46 – 72.90), female gender was −48.71 %, 95 % CI ( −81.33 – −21.97), and alcohol & smoking was 14.90 %, 95 % CI (2.95 – 25.38). After adjusting for age and gender, the population attributable fraction of ESCC due to a combination of alcohol & smoking was 12.66 %, 95 % CI (−1.29 – 24.61) (Table 4).

Discussion

This is the first study to report PAFs for ESCC risk factors smoking and alcohol in an ESCC high-risk region in sub-Saharan Africa. Our study describes a low population attributable fraction of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma due to smoking and alcohol use in southwestern Uganda i.e., if smoking and alcohol use were eliminated in the rural population of southwestern Uganda, approximately 13 % of new esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cases could be avoided. This is lower than an estimated two-thirds and three-fourths population attributable fractions of ESCC for smoking and alcohol respectively, from priorstudies in high - risk and low - risk populations [12–15]. However, our results corroborate findings from one of the ESCC highest risk areas of northern China (Linxian County) where it has been suggested that alcohol and tobacco consumption are not the major risk factors for ESCC [21]. We posit that ESCC in this population results from multifactorial interactions of environmental factors, diet, and genetics [22–24] and not individual factors (alcohol and smoking) only.

The PAFs stratified by gender indicated that a higher percentage of ESCC would be prevented by change in gender which confirms that male gender confers a higher risk of ESCC as described by other studies [25, 26] presumably due to the high exposure to smoking and alcohol [26] or hormonal differences [27, 28]. In fact, the PAFs of smoking and alcohol as individual factors indicated that smoking had the highest PAF for ESCC in the unadjusted (19.7 %) as well as in the gender and age adjusted analyses (15.6 %). The PAF estimates for alcohol use were lowest even when compared with the PAF of the combined term of smoking and alcohol. This finding emphasizes that smoking (and less so alcohol use) is more prevalent in endemic regions translating into a high attributable fraction. Therefore, other factors including genetic variations, socioeconomic disparities, dietary factors, and possibly infectious causes, are may contribute to the population attributable fraction differences in this population [29].

Our study highlights ESCC occurring in younger age (<60 years) despite the global trends that esophageal squamous cell cancer is known to occur in the late 6th and 7th decades of life [30] and cases occurring before the age of 40 years are rare [31]. Within Uganda, esophageal cancer has been described in older age (>60 years) in central [32] and northern region [33]. However, our finding is similar to reports from southwestern Kenya, which showed a significant number of esophageal cancer patients presenting at very young ages [31, 34]. This supports our assertion of peculiar risk factors for ESCC that likely afflicts earlier in life such that there is earlier presentation of disease at younger age. Taken together, we posit that maybe there may be unique carcinogenic risk factor(s) for ESCC leading to early onset and/or radid progression.

This data should be interpreted in the context of the study design. As patients studied were referred for endoscopy to a referral center, referral bias likely exists and they may not accurately represent the general population.

As with all non-randomized observational studies, our study could suffer from unmeasured or residual confounding on the associations between younger age (<40 years) and ESCC. However, since our results are similar to findings in high-risk populations, such confounders are more likely to represent actual mediators of the relationship between young age and ESCC, than true confounder per se.

Conclusion

In this study, only 13 % of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cases would be avoided if alcohol and smoking were discontinued in a rural population of southwestern Uganda, suggesting that important risk factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in this population are not known. Future work should focus on relationships between environmental, infections, diet, genetic, and epigenetic factors as esophageal squamous cell carcinoma risks in this population.

References

Hiripi E, Jansen L, Gondos A, Emrich K, Holleczek B, Katalinic A, Luttmann S, Nennecke A, Brenner H. Survival of stomach and esophagus cancer patients in Germany in the early 21st century. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(7):906–14.

Wang G-Q, Jiao G-G, Chang F-B, Fang W-H, Song J-X, Lu N, Lin D-M, Xie Y-Q, Yang L. Long-term results of operation for 420 patients with early squamous cell esophageal carcinoma discovered by screening. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77(5):1740–4.

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90.

Vaughan TL, Davis S, Kristal A, Thomas DB. Obesity, alcohol, and tobacco as risk factors for cancers of the esophagus and gastric cardia: adenocarcinoma versus squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 1995;4(2):85–92.

Farhadi M, Tahmasebi Z, Merat S, Kamangar F, Nasrollahzadeh D, Malekzadeh R. Human papillomavirus in squamous cell carcinoma of esophagus in a high-risk population. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(8):1200–3.

Petrick J, Wyss A, Butler A, Cummings C, Sun X, Poole C, Smith JS, Olshan AF. Prevalence of human papillomavirus among oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma cases: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(9):2369–77.

Castellsague X, Munoz N, De Stefani E, Victora CG, Castelletto R, Rolón PA. Influence of mate drinking, hot beverages and diet on esophageal cancer risk in South America. Int J Cancer. 2000;88(4):658–64.

Ziegler RG. Vegetables, fruits, and carotenoids and the risk of cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53(1):251S–9S.

Qiao Y-L, Dawsey SM, Kamangar F, Fan J-H, Abnet CC, Sun X-D, Johnson LL, Gail MH, Dong Z-W, Yu B, Mark SD, Taylor PR. Total and cancer mortality after supplementation with vitamins and minerals: follow-up of the Linxian General Population Nutrition Intervention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009. doi:10.1093/jnci/djp037.

Tran GD, Sun XD, Abnet CC, Fan JH, Dawsey SM, Dong ZW, Mark SD, Qiao YL, Taylor PR. Prospective study of risk factors for esophageal and gastric cancers in the Linxian general population trial cohort in China. Int J Cancer. 2005;113(3):456–63.

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervi M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1. 0 Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2013. 2012.

Engel LS, Chow WH, Vaughan TL, Gammon MD, Risch HA, Stanford JL, Schoenberg JB, Mayne ST, Dubrow R, Rotterdam H. Population attributable risks of esophageal and gastric cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(18):1404–13.

Brown LM, Hoover RN, Greenberg RS, Schoenberg JB, Schwartz AG, Swanson GM, Liff JM, Silverman DT, Hayes RB, Pottern LM. Are racial differences in squamous cell esophageal cancer explained by alcohol and tobacco use? J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86(17):1340–5.

Siemiatycki J, Krewski D, Franco E, Kaiserman M. Associations between cigarette smoking and each of 21 types of cancer: a multi-site case-control study. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24(3):504–14.

Rothman KJ. The proportion of cancer attributable to alcohol consumption. Prev Med. 1980;9(2):174–9.

Statistics UBo. Statistical Abstract 2013. Statistics UBo, editors. Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics; 2013

Mapstone N, Group RCSW. Dataset for the histopathological reporting of oesophageal carcinoma. London: Royal College of Pathologists; 2007.

Lofdahl HE, Du J, Nasman A, Andersson E, Rubio CA, Lu Y, Ramqvist T, Dalianis T, Lagergren J, Dahlstrand H. Prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in relation to anatomical site of the tumour. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e46538.

Antunes JLF, Toporcov TN, Biazevic MGH, Boing AF, Scully C, Petti S. Joint and independent effects of alcohol drinking and tobacco smoking on oral cancer: a large case-control study. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68132.

Benichou J, Gail MH. Variance calculations and confidence intervals for estimates of the attributable risk based on logistic models. Biometrics. 1990;46(4):991–1003.

Yu Y, Taylor PR, Li J-Y, Dawsey SM, Wang G-Q, Guo W-D, Wang W, Liu B-Q, Blot WJ, Shen Q. Retrospective cohort study of risk-factors for esophageal cancer in Linxian, People’s Republic of China. Cancer Causes Control. 1993;4(3):195–202.

Chen J, Huang Z-J, Duan Y-Q, Xiao X-R, Jiang J-Q, Zhang R. Aberrant DNA methylation of P16, MGMT, and hMLH1 genes in combination with MTHFR C677T genetic polymorphism and folate intake in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(10):5303–6.

Huang Y, Chang X, Lee J, Cho YG, Zhong X, Park IS, Liu JW, Califano JA, Ratovitski EA, Sidransky D. Cigarette smoke induces promoter methylation of single‐stranded DNA‐binding protein 2 in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(10):2261–73.

Matejcic M, Iqbal Parker M. Gene-environment interactions in esophageal cancer. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2015;52(5):211–31.

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–917.

Castellsagué X, Muñoz N, De Stefani E, Victora CG, Castelletto R, Rolón PA, Quintana MJ. Independent and joint effects of tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking on the risk of esophageal cancer in men and women. Int J Cancer. 1999;82(5):657–64.

Dong J, Jiang S-W, Niu Y, Chen L, Liu S, Ma T, Chen X, Xu L, Su Z, Chen H. Expression of estrogen receptor α and β in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2013;30(6):2771–6.

Tihan T, Harmon J, Wan X, Younes Z, Nass P, Duncan K, Duncan MD. Evidence of androgen receptor expression in squamous and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Anticancer Res. 2000;21(4B):3107–14.

Gibbons MC, Brock M, Alberg AJ, Glass T, LaVeist TA, Baylin S, Levine D, Fox CE. The sociobiologic integrative model (SBIM): enhancing the integration of sociobehavioral, environmental, and biomolecular knowledge in urban health and disparities research. J Urban Health. 2007;84(2):198–211.

Zhang H, Chen S-H, Li Y-M. Epidemiological investigation of esophageal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(12):1834–5.

Dawsey SP, Tonui S, Parker RK, Fitzwater JW, Dawsey SM, White RE, Abnet CC. Esophageal cancer in young people: a case series of 109 cases and review of the literature. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e14080.

Ocama P, Kagimu MM, Odida M, Wabinga H, Opio CK, Colebunders B, van Ierssel S, Colebunders R. Factors associated with carcinoma of the oesophagus at Mulago Hospital, Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2008;8(2):80–84.

Alema O, Iva B. Cancer of the esophagus; histopathological sub-types in northern Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14(1):17–21.

Parker RK, Dawsey SM, Abnet CC, White RE. Frequent occurrence of esophageal cancer in young people in western Kenya. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23(2):128–35.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank PENTAX medical and Michael Fina for their donation of a gastroscope to make this research possible.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

SO, RO, CLA, DCC, and KEC, conceptualized and designed this study; SO, CC, RO, BN, CT, CLA, and DM, collected data; SO, CC, RO, BN, CT, CLA, DM, DCC, and KEC analyzed, interpreted data, and wrote manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors prepared this report in their roles as employees of their respective institutions. They have no financial or other potential conflict of interest with regard to this manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Mbarara University of Science & Technology research ethics committee approved and waivered the requirement for individual patient consent since this was a retrospective analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Okello, S., Churchill, C., Owori, R. et al. Population attributable fraction of Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma due to smoking and alcohol in Uganda. BMC Cancer 16, 446 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2492-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2492-x