Abstract

Background

With improvements in treatment of cancer, more men of fertile age are survivors of cancer. This study evaluates trends in birth rates among male cancer survivors and mortality rates of their offspring.

Methods

From the Swedish Multi-generation Register and Cancer Register, we identified 84,752 men ≤70 years with a history of cancer, for which we calculated relative birth rates as compared to the background population(Standardized Birth Ratios, SBRs). We also identified 126,696 offspring of men who had cancer, and compared their risks of death to the background population(Standardized Mortality Ratio, SMRs). Independent factors associated with reduced birth rates and mortality rates were estimated with Poisson modelling.

Results

Men with a history of cancer were 23 % less likely to father a child compared to the background population(SBR 0.77, 95 % Confidence Interval[CI] 0.75–0.79). Nulliparous men were significantly more likely to father a child after diagnosis (SBR 0.81, 95 % CI 0.79–0.83) compared to parous men (SBR 0.68, 95 % CI 0.66–0.74). Cancer site(prostate), onset of cancer during childhood or adolescence, parity status at diagnosis(parous), current age(>40 years) and a recent diagnosis were significant and independent predictors of a reduced probability of fathering a child after diagnosis.

Of the 126,696 children born to men who have had a diagnosis of cancer, 2604(2.06 %) died during follow up. The overall mortality rate was similar to the background population(SMR of 1.00, 95 %CI 0.96–1.04) and was not affected by the timing of their birth in relation to father’s cancer diagnosis.

Conclusion

Male cancer survivors are less likely to father a child compared to the background population. This is influenced by cancer site, age of onset and parity status at diagnosis. However, their offspring are not at an increased risk of death.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With early diagnosis, advancing treatment and improved survival rates of childhood and early adult cancer, an increasing proportion of boys and young men with cancer are more likely to survive their disease to reach reproductive ages [1]. This has led to an increased interest in the quality of life and reproductive potential of this group of cancer survivors. Some forms of cancer may directly affect fertility through adverse effects on the physiology of the male reproductive organs or endocrine glands; eg. Testicular cancer. Loco-regional or systemic treatment procedures such as pelvic surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy may induce temporary or permanent infertility in men through the disruption of ejaculatory functions or cytotoxic effects on spermatogenesis [2, 3].

The advances in medicine have had a contrasting effect on fertility in cancer survivors. On one hand, newer chemotherapeutic treatment regimes (eg. the use of procarbazine with alkylating agents in Hodgkin’s disease) or gonadal/whole body irradiation has a higher chance of sterilising patients [4, 5]. However, the development of fertility preservation techniques in men, such as semen cryopreservation and testicular sperm extraction; in combination with artificial reproductive techniques of in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) or intra-cystoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) have offered men a possibility of parenthood after cancer [4, 5].

Psychologically, the diagnosis of cancer may increase the value placed on family and the importance of parenthood for the cancer survivors [6, 7]. However, this may be contradicted with his own uncertainties of his cancer prognosis, a perceived risk of passing the cancer susceptibility on to his offspring, treatment-related harm to the offspring and other social and cultural influences. Studies have shown that cancer patients are less likely to father a pregnancy after their disease as compared to their siblings [8, 9].

Various studies have not shown any adverse pregnancy outcomes for the partners of male childhood cancer survivors [10, 11]. However, few studies have been conducted in adult male cancer survivors. It is unclear if the exposure to (the effects of) diagnostic investigations, radiation therapy, and systemic treatment before and around the time of birth may have any adverse effects on spermatogenesis and the subsequent wellbeing of the offspring.

In this study, we aim to evaluate trends in birth rates among Swedish male cancer survivors by age and over time, as well as the factors which independently affect their probability of fatherhood after diagnosis. We also aim to assess the mortality risks in offspring of these men with a history of cancer in relation to timing of birth and cancer site.

Methods

Study design

We used the Multi-Generation Register(MGR) [12], the Swedish Cancer Register [13], the Cause of Death Register, and the Migration Register for this study. The unique national registration numbers accorded for each Swedish individual was used as a linkage between the registries and the Censuses of 1960, 1970, 1980, and 1990, to obtain further information on the socioeconomic status of each Swedish citizen. Information was extracted on cancer site as defined by the International Classification of Diseases, Revision 7 code (ICD7) [14]. Socioeconomic status was estimated based on information about the highest level of employment in the household given in the Censuses and was categorized into five groups; blue collar workers, white collar workers, self-employed workers, farmers and unclassified. In total, this database contains more than 11 million individuals, belonging to around three million families and included more than a million individuals with cancer diagnosed between 1958 and 2001 [12]. The study design was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board at Karolinska Institutet, Sweden whereby the need for individual consent from the participants was deemed unnecessary.

Birth rates among male cancer survivors

Our study base consisted of all men aged 16 to 70 years, born after 1931, who were alive between 1961 and 2002 and present in the Multi-Generation Register. The partners or spouse of these men were identified and tracked for up to 10 months after the men have passed away/emigrated to ensure all information of their offspring were included. For each man, we ascertained the number and dates of live child births (multiple pregnancies were counted as one event/birth), with their partners or spouse, socioeconomic status, date of cancer diagnosis (if present) and followed them until death, emigration or end of follow up (31st December 2002), whichever came first. End of follow-up was chosen at 31st December 2002, where records of cancer, death, migration and socioeconomic status were all available on the numerous registers. For men diagnosed with cancer, we calculated the proportion and relative probability of fathering an offspring after diagnosis.

We included all births >1 year after diagnosis, as most patients would have received complete information on treatment plan and prognosis by then, with the decision to have an offspring considered with the knowledge of the cancer diagnosis. For the background population, cancer-free men in the background population were matched to the male cancer survivors according to attained age and year of birth, and the number of live child births of the spouse of these men in the background population was then ascertained. Using the above criteria, there were 4,032,096 Swedish men in the Swedish MGR, where 87,302 men had a history of cancer (Fig. 1). Over the study period, 2550 participants (0.03 %) were lost to follow-up and 883,548 (22.4 %) were excluded from the study population as they were out of the observed age range of 16 to 70 years old or had emigrated. Missing data is equally likely in both the male cancer survivors and the background population which is why we chose to use standardized birth ratio to handle the non-differential bias.

Mortality rate among offspring of male cancer survivors

For the offspring of fathers with a history of cancer we extracted information on date of birth, date of death and cause of death. Each individual offspring in multiple pregnancies was counted separately. 126, 696 offspring of 64,451 men in the study population with cancer and whose partners gave birth during the observation period were identified and followed up for a median of 32.3 years (range 0–42.9 years). Causes of death were regrouped as congenital anomalies (ICD7: 750–759), perinatal conditions (ICD7: 760–776),neoplasms (ICD7: 140–239) and others (i.e. all remaining causes combined). Offspring were followed from birth until death, emigration, or end of follow-up (31st December 2003), whichever came first.

In order to investigate the association between timing of birth in relation to the father’s cancer diagnosis, we categorized offspring into three groups: offspring born more than 1 year before their father’s cancer diagnosis (Group 1), offspring born between 1 year before and 1 year after their father’s diagnosis (Group 2), and offspring born more than 1 year after their father’s cancer diagnosis (Group 3). The rationale behind these (arbitrary) cut off levels was that children born more than 1 year before their father’s diagnosis were not exposed to the cancer process itself, nor to the diagnostic investigations, or treatment. Children born around their father’s diagnosis may have been conceived with sperm that were directly exposed to the cancer process itself, the diagnostic investigations (involving ionizing radiation), and the cancer treatment. Finally, children born more than 1 year after their father’s diagnosis have not been directly exposed to cancer treatment, but mutagenic effects of cancer treatment or damage to the reproductive organs in the father may still affect their outcome.

Statistical analysis

Relative birth rates were expressed as a Standardized Birth Ratios (SBRs), i.e. the ratio of observed births in our study group to the expected number of births, based on birth rates in the background population. Person-years at risk of giving birth were calculated from 1 year after the time of cancer diagnosis or 16th birthday, whichever came later; until 10 months after date of death or emigration, 17th birthday or end of follow up (31st December 2003), whichever came first. Background birth rates were derived using birth rates for all men present in the Multi-Generation Register [12]. The expected number of births was calculated by multiplying the 5-year age- and calendar period specific birth rates in the background population by correspondingly stratified person-years at risk and summing all the products. We then compared relative birth rates by age at onset (childhood-below the age of 13 years-, adolescence−13 to 18 years-and adulthood > 18 years), attained age, year and parity status at diagnosis, cancer site, time since diagnosis, attained year, and socioeconomic status.

Relative risks of death in offspring were expressed as Standardized Mortality Ratios(SMRs), i.e. the ratio of observed to expected number of deaths. Person-years were calculated as the time from the child’s birth to death, emigration, or end of follow up (31stDecember 2003), whichever came first. Background mortality rates were derived using mortality rates of 3,620,127 offspring of 3,060,345 men present in the Multi-Generation Register (Fig. 1). The expected number of deaths was calculated by multiplying the 5-year age and calendar period specific mortality rates in the background population by correspondingly stratified person-years at risk in the cohort and summing all the products. We calculated overall SMRs by timing of birth in relation to father’s diagnosis and stratified attained age of the offspring and cancer site.

A multivariate Poisson regression modelling was performed on data from the study population only, to identify independent predictors of fatherhood after diagnosis and the mortality of the offspring of cancer survivors. The relative risks of fatherhood were expressed as Birth Rate Ratios (BRRs), which were adjusted for parity status at diagnosis, cancer site, age and year of diagnosis, time since diagnosis, calendar period, attained age and socioeconomic status. The BRRs was also used to estimate whether factors linked with mortality in the offspring on univariate analysis remained significantly associated after adjustment for father’s age at childbirth, mother’s age at childbirth, attained age of child, calendar year and socioeconomic status. Relative risks were expressed as Mortality Rate Ratios (MRRs). Finally, we compared causes of death in offspring of fathers with cancer to causes of death of children in the background population. Chi-square and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to test for differences in the distribution of causes of death. Data preparation and analysis was done with SAS® version 9.2(SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

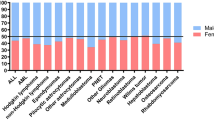

The study population included 3,145,998 Swedish men, of whom 84,752 (2.8 %) were diagnosed with cancer before age 70 years (Fig. 1). Most of the men (95.7 %) were diagnosed with cancer in adulthood (19–70 years), with the commonest site being digestive tract (n = 14,817) and prostate (n = 11,281) (Table 1). Among the cancer survivors (group 3), 4973 (5.9 %) men had partners who gave birth to a total of 7910 births 1 year after their diagnosis. A higher proportion of men who were diagnosed in childhood (19.5 %) and adolescence (22.8 %) fathered a child after the diagnosis, compared with men diagnosed in adulthood (5.2 %).

Men diagnosed with cancer were 23 % less likely to have a child (SBR 0.77, 95 % CI 0.75–0.79) compared to the background population (Table 2). This remained fairly consistent over calendar time. Men who were diagnosed in childhood had a significantly lower birth rate (SBR 0.62, 95 % CI 0.57–0.67) than men diagnosed in adulthood (SBR 0.80, 95 % CI 0.78–0.82) when compared to the background population. Survivors of skin, thoracic cancer and head and neck had a birth rate similar to the background population (SBR 0.98 [0.92–1.04],0.92 [0.74–1.11] and 0.90 [95 % CI 0.80–1.01] respectively); whilst survivors of prostate, brain and eye, and hematopoietic cancers had a significant decrease in their birth rates (SBR 0.24 [95 % CI 0.06–0.54], 0.65 [0.62–0.69] and 0.66 [0.62–0.70] respectively) compared to the background population.

Men who were parous at the point of cancer diagnosis had a lower birth rate compared to those who were nulliparous (SBR 0.68 [0.66–0.74], 0.81 [95 % CI 0.79–0.83] respectively). This was particularly pronounced in parous men who were diagnosed with prostate, thoracic and haematopoietic cancers (SBR 0.22 [0.04–0.53], 0.48 [0.40–0.88] and 0.53 [0.46–0.61] respectively) (Table 3). In contrast, men who were nulliparous at point of diagnosis of thoracic, skin, head and neck and digestive cancers had birth rates which were similar to the background population (SBR 1.20 [0.94–1.49], 1.10 [1.01–1.18], 1.06 [0.92–1.22], 0.97 [0.87–1.08] respectively). However, nulliparous men who were diagnosed with brain and eye, haematopoietic and reproductive organs cancer still had significantly lower birth rates compared to the background population (SBR 0.65 [0.60–0.69], 0.70 [0.65–0.75], 0.75 [0.68–0.77] respectively).

Multivariate Poisson modelling, adjusting for calendar period, socioeconomic status, and year of diagnosis showed that parity status at diagnosis, cancer site, age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis and attained age were all independently and significantly associated with the probability of giving birth after cancer diagnosis (Table 4). Being parous at diagnosis, a diagnosis of prostate cancer, older attained age (41–70 years), diagnosis in childhood and adolescence (0–12 and 13–18 years) and a recent diagnosis (1–5 and 6–10 years) were significant and independent predictors of a reduced probability of giving birth after diagnosis. Men diagnosed in adulthood, increased time since diagnosis, cancer survivors aged 26–35 and survivors of thoracic and head and neck cancers were most likely to father an offspring.

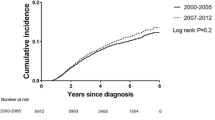

Between 1961 and 2003, 126,696 children of the total 3,746,823 children were born to men who have had a diagnosis of cancer at any point in their lives (Fig. 1). These children were divided into groups based on the timing of their birth in relation to the diagnosis of their father’s cancer, where 115,938 children were born more than a year before their father’s cancer diagnosis, 2707 children born around the time of their father’s diagnosis and a further 8051 children born more than a year after their father’s diagnosis (Table 5). There was a total of 2604 deaths in these offspring, where 2500 (2.16 %) of the deaths occurred in children who were born more than a year before their father’s cancer diagnosis, 31 (1.15 %) deaths occurred in children born around the time of their father’s diagnosis and 73 (0.91 %) deaths occurred in children born more than a year after their father’s diagnosis.

Overall, mortality rate of offspring of fathers who have had a cancer diagnosis was similar to that of the background population (SMR 1.00, 95 % CI 0.96–1.04). This remained similar across all three groups of children, regardless of the timing of their birth in relation to their father’s cancer diagnosis (Table 6). There was no significant increase in mortality rate as the child grew older in all three groups of children. Variation in the father’s cancer site, age at diagnosis and age at childbirth did not cause a significantly higher mortality rate in the offspring compared to the background population. However, offspring of fathers in Group 3 who were parous at the start of observation period were shown to have a higher mortality rate compared to the background population (SMR 1.54, 95 % CI 1.06–2.10).

After multivariate analysis with Poisson regression, adjusting for father’s age at childbirth, mother’s age at childbirth, father’s socioeconomic factor, attained age of the child and calendar period, the mortality risk of the offspring across all three groups of children were similar to the background population, suggesting that timing of birth of offspring in relation to the father’s diagnosis of cancer does not affect the child’s mortality risk (Table 7). However, increasing father’s age at childbirth and increasing mother’s age at childbirth were shown to be independent risk factors for increasing mortality risk of the offspring. Of note, children whose mothers were unknown were shown to be at an increased mortality risk. In this study, there was no significant difference between the causes of death (congenital anomalies, p = 0.172; perinatal conditions, p = 0.172; neoplasms, p = 0.368) and the timing of the birth of the offspring of fathers with or without a history of cancer (data not shown).

Discussion

This population based study shows that male cancer survivors are 23 % less likely to father an offspring compared to the background population. However, there is a large variation in birth rates depending on cancer site, age at diagnosis, parity status at diagnosis and time since diagnosis. Independent predictors for low birth rate following a cancer diagnosis were men who had prostate cancer, parous at diagnosis, recent diagnosis, diagnosed in childhood and aged over 40 years.

There are several reasons for the decreased birth rates among cancer survivors, contributed by the cancer itself, the side effects of systemic or locoregional treatment and psychosocial factors. There is a direct pathogenetic relationship between gonadal function and some malignancies such as testicular cancer. The adverse effects on gonadal function may also be mediated centrally through the effects on the hypothalamo-pituitary hormone axis. Chemotherapeutic agents, particularly alkylating agents (cyclophosphamide), procarbazineand platinum-agent (cisplatin) have been identified to be gonadotoxic [15, 16]. Radiotherapy with total-body irradiation and abdomino-pelvic irradiation can also affect reproductive function. The extent and reversibility of these gonadal effects tend to be dose dependent and vary by the age of the patient, type of cytotoxic regime [4, 8, 15] and the field, total dose and fractionation schedule of radiotherapy [17–20]. However, there remains a risk of permanent sterility.

A population based study conducted by Syse et al. in Norway had a similar finding to our study, where male survivors of cancer had a 24 % lower first birth rate compared to the background population of men without cancer of similar age, education in a similar period of time [21]. A separate study by Green et al. evaluated the long-term fertility of 6224 male survivors in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study through questionnaires, which showed that male survivors were 44 % less likely to father a pregnancy than their siblings who had not undergone cancer treatment[8].

The diagnosis of cancer can also affect the survivors socially and psychologically to impact their attitude towards parenthood. With increased concerns of potential disease recurrence, concerns about dying and leaving their spouse to face single parenthood and not living long enough to see their children grow up and fear for the health of their offspring can impact negatively on their desire to have children [6, 22]. Also, cancer survivors are less likely to have a stable income and stable relationship with poorer job prospects and poorer health related quality of life; which can all affect their birth rates [23–26].

We observed very different fertility patterns for men with or without a child at diagnosis. Men who were parous at diagnosis had a significantly lower birth rate than those who were nulliparous, which is consistent with previously reported studies of fertility in cancer survivors [9, 21, 27]. This was reflected in all but one of the cancer sites (Breast Cancer) in our study. This finding is comparable to that in nulliparous female survivors of cancer who had similar birth rates to the background population in 8 out of 12 cancer sites [28]. This suggests that the true average ‘infertility’ in men following many types of cancers is only marginally less, if any, than the birth rates observed in cancer-free men. This finding is promising, as Mancini et al. showed that 33.5 % of fertile cancer survivors aged 20–44 desired to be parents and had the intention for additional children [29].

We identified several independent predictors of birth following a cancer diagnosis. These included parity status at diagnosis, cancer site, age at and time since diagnosis. Differences in birth rates based on age at diagnosis are likely related to the improvements in and increasing use of fertility preservation techniques, such as sperm banking and in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) in adolescents and adults diagnosed with cancer; as well as the increased toxicity of systemic treatment in children (0–12 years) and the inability to utilise sperm-banking for pre-pubertal males. Also men with prostate cancer are likely to be older and thus may have completed their family and no longer desire to have any children, which can contribute to a lower birth rate. The independent effect on increased birth rates of time since diagnosis may represent a physical and psychological perception of ‘cure’ from cancer, and return to normal function, where survivors may then be more able and willing to father a(nother) child.

Our study has also shown that offspring born to fathers who have cancer have similar mortality rates to the background population, and are not at an increased risk of death. This is consistent with previous studies which suggest that offspring of fathers who have had cancer have few other complications or adverse outcomes compared to the background population [30, 31]. This remained constant and was not affected by the timing of birth in relation to the cancer diagnosis. This is starkly different from mothers with cancer, where the timing of birth plays a major role, with offspring born around the time of diagnosis having a 66 % increased risk of death [32]. This is thought to be related to the intrauterine exposure to cancer treatment (chemotherapeutic agents and radiotherapy).

However, it is noted that offspring of parous men who were born after diagnosis had a higher mortality rate compared to the background population. This, coupled with the lower birth rates in men who were parous at diagnosis suggests that this particular group of men may need increased support, should they desire to have further offspring after their cancer diagnosis and treatment.

The mortality rate of offspring born around or after the time of diagnosis was not influenced by the attained age of the child, father’s socioeconomic status or the site of the father’s cancer. However, increasing father’s age at childbirth and increasing mother’s age at childbirth were shown to be independent risk factors for increasing mortality risk of the offspring. This is similar to the background population, where previous studies in a normal (non-cancer) population, have demonstrated a higher mortality rate in offspring of fathers aged 45 years or more [33] and mothers aged 35 years or more [34–36].

With over 80,000 men who were diagnosed with cancer who had over 120,000 offspring in a span of 40 years, our study is to our best knowledge, one of the largest studies evaluating the birth rates of male cancer survivors and the mortality rates of their offspring. The large population-based design allowed for an unbiased ascertainment of cancers, births and deaths. By calculating standardized birth ratios and standardised mortality ratios, we take into account societal changes in reproductive behaviour and mortality over time.

Weaknesses of our study include the lack of information of treatment details, which would have allowed for a better understanding of the observed trends. There was also absence of information on spontaneous or induced abortions in the partner/spouse, as well as the use of fertility preservation techniques which may have contributed to these findings. Furthermore, the measurement of fertility was implied through the birth rates of the subject’s partner/spouse, without considering possible paternal discrepancy or misattributed paternity. Any bias arising from this is difficult to predict as non-paternity rates vary greatly across populations (from 0.8 to 30 %) and have been associated with different demographic factors [37]. Our study included a substantial proportion of men who were treated decades ago and exposed to treatment regimens that may no longer be the standard of care. However, we observed no period effects, suggesting that there were no major changes in birth rates of the cancer survivors and mortality risks among their offspring over time. The study data was not extended beyond 2003 as more recent birth data among cancer survivors was not available.

Conclusions

In summary, a diagnosis of cancer has an important impact on a man’s likelihood of fathering a child after the diagnosis. In this study, we observed the trends of changing birth rates in male Swedish cancer survivors, which are influenced by the site of cancer, age at and time since diagnosis. There is also a significant difference between survivors who are nulliparous vs. those who are parous at diagnosis, suggestive of a psychological element which may over-ride the physical ability of the survivor to have a(nother) child. However, offspring of male cancer survivors have a similar mortality rate to the background population, which is not influenced by the timing of their birth in relation to the cancer diagnosis, attained age of the child, father’s socioeconomic status or the site of the father’s cancer. Identifying men at increased risk of sub-fertility or infertility post-diagnosis, particularly those with a strong desire for parenthood; will allow for appropriate counselling and utilisation of fertility preservation techniques to give the men the possibility of parenthood after a cancer diagnosis.

Abbreviations

- BRR:

-

birth rate ratios

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- ICD7:

-

International classification of diseases, Revision 7 code

- ICSI:

-

intracytoplasmic sperm injection

- IVF:

-

in-vitro fertilisation

- MGR:

-

multi-generation register

- MRR:

-

mortality rate ratios

- SBR:

-

standardized birth ratios

- SMR:

-

standardized mortality ratios

References

Fossa SD, Magelssen H. Fertility and reproduction after chemotherapy of adult cancer patients: malignant lymphoma and testicular cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15 Suppl 4:259–65.

Giwercman A, Peterson PM: Cancer and male infertility. In: Bailliere's Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. edn.: Harcourt Publisher's; 2000: 453–471.

Meirow D, Schenker JG. Cancer and male infertility. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(8):2017–22.

Wallace WH, Anderson RA, Irvine DS. “Fertility preservation for young patients wtih cancer: who is at risk and what can be offered?lancet”. Oncology. 2005;6(4):209–18.

Dohle GR. Male infertility in cancer patients: review of the literature. Int J Urol. 2010;17:327–31.

Schover LR, Brey K, Lichtin A, Lipshultz LI, Jeha S. Knowledge and experience regarding cancer infertility, and sperm banking in younger male survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1880–9.

Langeveld NE, Stam H, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF. Quality of life in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10:579–600.

Green DM, Kawashima T, Stovall M, Leisenring W, Sklar CA, Mertens AC, et al. Fertility of male survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):332–9.

Madanat LMS, Malila N, Dyba T, Hakulinen T, Sankila R, Boice RD, et al. Probability of parenthood after early onset cancer: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(12):2891–8.

Green DM, Whitton JA, Stovall M, Mertens AC, Donaldson SS, Ruymann FB, et al. Pregnancy outcome of partners of male survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(4):716–21.

Chow EJ, Kamineni A, Daling JR, Fraser A, Wiggins CL, Mineau GP, et al. Reproductive outcomes in male childhood cancer survivors: a linked cancer-birth registry analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(10):887–94.

Sweden S. Multi-generation register 2003 a description of contents and quality Sweden: statistics. SE-701 89 Örebro, Sweden: Publication Services; 2004.

Mattson BWA. Completeness of the swedish cancer registry. Acta Radiol. 1984;23:305–13.

World Health Organization (1957). Manual of the international statistical classification of diseases, injuries, and causes of death: based on the recommendations of the seventh revision Conference, 1955, and adopted by the ninth World Health Assembly under the WHO Nomenclature Regulations. Geneva: 1957.

Mackie EJ, Radford M, Shalet SM. Gonadal function following chemotherapy for childhood Hodgkin's disease. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;27(2):74–8.

Waring AB, Wallace WH. Subfertility following treatment for childhood cancer. Hosp Med. 2000;61(8):550–7.

Castillo LA, Craft AW, Kernahan J, Evans RG, Aynsley-Green A. Gonadal function after 12Gy testicular irradiation in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1990;18(3):185–9.

Howell S, Shalet S. Gonadal damage from chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1998;27(4):927–43.

Sklar CA, Robison LL, Nesbit ME, Sather HN, Meadows AT, Ortega JA, et al. Effects of radiation on testicular function in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the children cancer study group. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8(12):1981–7.

Sanders JE, Hawley J, Levy W, Gooley T, Buckner CD, Deeg HJ, et al. Pregnancies following high-dose cyclophosphamide with or without high-dose busulfan or total-body irradiation and bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1996;87(7):3045–52.

Syse A, Kravdal O, Tretli S. Parenthood after cancer—a population-based study. Psychooncology. 2007;16:920–7.

Zebrack BJ, Casillas J, Nohr L, Adams H, Zeltzer LK. Fertility issues for young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13(10):689–99.

Amir Z, Moran T, Walsh L, Iddenden R, Luker K. Return to paid work after cancer: a British experience. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1(2):129–36.

Gurney JG, Krull KR, Kadan-Lottick N, Nicholson HS, Nathan PC, Zebrack B, et al. Social outcomes in the childchood cancer survivor study cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2390–5.

Blaauwbroek R, Stant AD, Groenier KH, Kamps WA, Meyboom B, Postma A. Health-related quality of life and adverse late effects in adult (very) long-term childhood cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:122–30.

Greaves-Otte JGW, Greaves J, Kruyt PM, van-Leeuwen O, Van-der-Wouden JC, Van-der-Does E. Problems at social re-integration of long-term cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1991;27(2):178–81.

Magelssen H, Melve KK, Skjaerven R. Parenthood probability and pregnancy outcomes in patients with a cancer diagnosis during adolescence and young adulthood. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:178–86.

Hartman M, Liu J, Czene K, Miao H, Chia KS, Salim A, Verkooijen HM: Birth rates among female cancer survivors: a population-based cohort study. Cancer. 2013;119(10):1892-9. Epub ahead of print.

Mancini J, Rey D, Preau M, Corroller-Soriano AGL, Moatti J-P. Barriers to procreational intentions among cancer survivors 2 years after diagnosis: a french national cross-sectional survey. Psychooncology. 2011;20(1):12–8.

Nygaard R, Clausen N, Siimes MA, Marky I, Skjeldestad FE, Kristinsson JR, et al. Reproduction following treatment for childhood leukemia: a population-based propsective cohort study of fertility and offspring. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1991;19(6):459–66.

Fossa SD, Magelssen H, Melve K, Jacobsen AB, Langmark F, Skjaerven R. Parenthood in survivors after adulthood cancer and perinatal health in their offspring: a preliminary report. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;34:77–82.

Verkooijen HM, Ang JX, Liu J, Czene K, Salim A, Hartman M. Mortality among offspring of women diagnosed wtih cancer: a population-based cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(10):2432–8.

Zhu JL, Vestergaard M, Madsen KM, Olsen J. Paternal age and mortality in children. Eur J Epidemiol. 2008;23(7):443–7.

Fretts RC, Schmittdiel J, McLean FH, Usher RH, Godlman MB. Increased maternal age and the risk of fetal death. N Eng J Med. 1995;333:953–7.

Hansen JP. Older maternal age and pregnancy outcome: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1986;41(11):726–42.

Myrskyla M, Fenelon A. Maternal age and offspring adult health: evidence from the health and retirement study. Demography. 2012;49(4):1231–57.

Bellis MA, Hughes K, Hughes S, Ashton JR. Measuring paternal discrepancy and its public health consequences. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:749–54.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Swedish Research Council, Swedish Initiative for research on Microdata in the Social and Medical Sciences (SIMSAM), grant number 80748301; National Medical Research Council, Singapore (NMRC/1180/2008) and National University of Singapore Start-up Fund DPRT(Grant Number R-186-000-108-133).

Financial disclosure

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Authors’ contributions

SWT and LJ drafted the manuscript. JL and HM participated in the study design and performed the statistical analysis. AS, HMV and MH conceived the study and participated in the design of the study. KC obtained the datasets and assisted in revision of manuscript. MH coordinated the study and made revisions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, SW., Liu, J., Juay, L. et al. Birth rates among male cancer survivors and mortality rates among their offspring: a population-based study from Sweden. BMC Cancer 16, 196 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2236-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2236-y