Abstract

Background

Pancreatic panniculitis is a rare condition, which has only been described in relation with pancreatic diseases up to now. It is characterized by necrotizing subcutaneous inflammation and is thought to be triggered by adipocyte necrosis due to systemic release of pancreatic enzymes with consecutive infiltration of neutrophils. We present the first case of a patient with pancreatic panniculitis caused by pancreatic-type primary acinar cell carcinoma (ACC) of the liver and without underlying pancreatic disease.

Case presentation

A 73-year old Caucasian female patient was referred to our department with painful cutaneous nodules persisting for eight weeks and with marked lipasemia (~15000 U/l; normal range <60 U/l). Four weeks prior, several liver lesions had been detected. Empiric treatment with steroids did not show any effect. A biopsy of the skin nodules revealed “pancreatic” panniculitis, while abdominal imaging with ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging detected no abnormal pancreatic findings. Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the liver lesions showed infiltrates of an ACC. The patient died soon thereafter. Autopsy failed to reveal any other primary for the ACC, so that a pancreatic-type ACC of the liver was diagnosed by exclusion.

One hundred thirty cases of pancreatic panniculitis published within the last 20 years are reviewed. ACC of the pancreas is the most common underlying neoplastic condition. Patients with associated neoplasm are significantly older, take longer to be diagnosed and have higher lipase levels than patients with underlying pancreatitis.

Extrapancreatic pancreatic-type ACC is very rare, but shows the same biological features as ACC of the pancreas. It is believed to develop from metaplastic or ectopic pancreatic tissue. Up to now, no pancreatic panniculitis in extrapancreatic ACC has been described.

Conclusion

Pancreatic panniculitis should always be included in the differential diagnosis of lipolytic panniculitic lesions. It can be regarded as a facultative paraneoplastic phenomenon.

When suspected, a thorough work-up for identification of the underlying disease is mandatory and extrapancreatic lesions (e.g. liver) should also be considered. While administration of octreotide or steroids can sometimes alleviate symptoms, immediate treatment of the associated condition is the only effective management option.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Chiari was the first to describe the development of panniculitic lesions in patients with pancreatitis in 1883 [1]. Since then, several case reports and small case series have reported focal or generalized panniculitis in association with pancreatic diseases like acute or chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic carcinoma (ductal adenocarcinoma, acinar cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma) or intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) [2–6].

Up to 45 % of patients with pancreatic panniculitis show subcutaneous panniculitic nodules before the causal disease is recognized [2]. Therefore, these nodules can serve as an early and valuable clue to diagnosis of the underlying condition and trigger measurement of serum pancreatic enzymes, abdominal imaging or biopsy procedures. Histologic evaluation of the cutaneous lesions will typically reveal lobular neutrophilic necrotizing panniculitis intermingled with specific necrotic anucleate adipocytes called “ghost cells” [7].

The mechanism underlying the formation of panniculitic nodules in pancreatic panniculitis is poorly understood. However, it is commonly believed that systemically released pancreatic enzymes such as lipase and amylase cause distant lipolysis and fat necrosis with consecutive inflammatory reaction [8]. This is supported by the finding that the necrotic tissue stains positive for lipase [9]. However, serum levels of pancreatic enzymes do not correlate with clinical findings and similarly, in vitro experiments suggest that this explanation is not sufficient [10].

In addition to the cutaneous manifestation, arthritis is often found in patients with pancreatic panniculitis, clinically referred to as pancreatitis panniculitis polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome. It is thought that pancreatic enzymes are also able to trigger necrosis and inflammation in the synovium [11]. Furthermore, there are reports about panniculitis in the bone marrow, at submucosal sites or within the thoracic or peritoneal cavity [2, 11, 12].

Acinar cell carcinoma (ACC) is a rare pancreatic malignancy, representing about 1 % of all primary pancreatic neoplasms [13]. ACC is the most common malignancy found in patients with pancreatic panniculitis [14] and symptoms of pancreatic panniculitis can be found in up to 16 % of ACC patients [4]. On very rare occasions, pancreatic-type ACC can also arise as a primary neoplasm at extrapancreatic locations, such as liver, stomach, jejunum and colon [15–18]. In such cases, extrapancreatic ACC is believed to originate from either ectopic, metaplastic of transdifferentiated pancreatic tissue and shares biologic features with primary pancreatic ACC [15].

Here, we report the first case of pancreatic panniculitis in association with a primary pancreatic-type ACC of the liver without underlying pancreatic disease. Moreover, we present a review of case reports and case series of pancreatic panniculitis from the last 20 years, summarizing important knowledge and data about this disease entity.

Case presentation

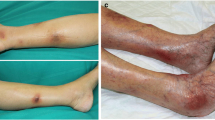

A 73-year-old Caucasian female patient was referred to our department for further work-up of painful cutaneous lesions (Fig. 1) and several masses within her liver.

Eight weeks prior, she had observed an erythematous nodule on her right chest. Subsequently, similar cutaneous lesions had developed on her arms and legs, and later also on her buttocks and back. She did not report any abdominal complaints. Outpatient treatment with topical and systemic steroids based on a suspicion of erythema nodosum (EN) did not yield substantial effect.

Four weeks prior, several liver lesions had been detected by ultrasound and were interpreted as metastases of a previously treated breast cancer. Additional imaging with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) had been carried out (Fig. 2) and confirmed the liver lesions.

As the nodules on her skin continued to spread and became increasingly painful, she was presented to the Department of Dermatology in our clinic. There, another attempt of steroids and an intensified local therapy resulted in no improvement of her clinical condition. Due to raising inflammatory parameters a work-up for possible infectious causes and an antibiotic therapy with piperacillin/tazobactam, and later with meropenem were initiated. A colonoscopy revealed two small polyps, which were completely removed. Pancreatic enzymes were markedly elevated. A punch biopsy of one of the skin lesions was obtained showing a lobular necrotizing panniculitis with “ghost cells” compatible with pancreatic panniculitis (Fig. 3). CT, MRI and repeated ultrasound examinations (Fig. 4) did not reveal any pathological findings in the pancreas. In contrast enhanced CT multiple sharply-bounded liver lesions were visualized in both liver lobes. Compared with the CT obtained during outpatient care, the lesions had progressed in size and measured from 1 cm to 6 cm. The perfusion pattern was non-hypervascular and the density was hypointense, partly comparable with the density of water. No necrotic areas were described within the lesions.

Because of a progressive worsening of her clinical condition and increasing laboratory markers of inflammation, the patient was referred to our Department of Internal Medicine. She complained about intensive pain all over her skin and required increasing dose rates of opioid analgetics. She did not report any weight loss, night sweats, fever, nausea or vomiting, abdominal pain or problems with food intake. Her past medical history was remarkable for invasive ductal breast cancer diagnosed in 1982 with local recurrences in 1990 and 2008. Moreover, a superficial spreading malignant melanoma had been treated in 2011 and a coronary artery disease with percutaneous coronary intervention in 2008 was reported. Family history was significant for malignant melanomas in all siblings and her mother. Continuous medication included acetyl salicylic acid, lercanidipine, metoprolol, enalapril and pravastatin with no recent change. No allergic condition was known.

On examination she was in poor general condition (ECOG performance status 4), tachycardic (102 bpm), slightly tachypnoeic (22/min) and normotensive (128/78 mmHg). Her temperature was 36.9 °C. Subcutaneous erythematous and painful nodules of 2–5 cm size were noticed throughout her integument. Some of them were spontaneously draining a brownish oily fluid. Moreover, more than 200 melanocytic nevi were observed on her skin. Examination of the head, especially focusing on the salivary glands was unremarkable. There was no pain on abdominal palpation, the liver was palpable 2 cm under the right costal arch and bowel sounds were normal. There was a positive tap sign on both patellae.

Laboratory results of interest were: leukocyte count 21.5 * 10^3/μl (ref. 4–10 * 10^3/μl), hemoglobin 10.0 g/dl (ref. 12–16 g/dl), ASAT 52 U/l (ref. < 35U/l), GGT 235 U/l (ref. <40 U/l), AP 186 U/l (ref. 35–105 U/l), lipase 14747 U/l (ref. < 60 U/l) and CRP 237 mg/l (ref. < 5 mg/l). Alpha-Amylase, uric acid, ACE, CEA, CA19-9 and AFP were within normal range. Serology for Yersinia enterocolitica and pseudotuberculosis was negative, as well as testing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis and atypical mycobacteria. Rheumatologic testing including ANAs and ANCAs was unremarkable.

Screening for possible infectious foci did not reveal any other source explaining the elevated CRP. Therefore, it was attributed to the skin lesions, which displayed clinical signs of inflammation and were partly draining pus in the further course. However, as microbiological evaluation was not able to prove any causative organism and inflammation markers were not substantially declining despite escalation of antibiotic treatment with additional vancomycin, skin lesions were classified as sterile. Leukocytosis was explained by concomitant steroid therapy.

Ultrasound displayed several liver lesions in both lobes with a maximum size of 53 mm. The pancreas was homogeneous and free of focal lesions. The pancreatic duct was not dilated and no avascular areas could be detected upon administration of ultrasound contrast agent. Ultrasound-guided puncture of one of the liver masses was performed leading to the histopathological diagnosis of a pancreatic-type ACC.

Unfortunately, the condition of the patient had severely deteriorated in the meantime with further exacerbation of pain, increasing tachycardia and hypotension. Therefore, no tumor-specific treatment could be initiated. The patient died ten days after admission to our ward.

Pathological and autopsy findings

Histopathological analysis of the core biopsy obtained from the liver mass revealed a cellular epithelial neoplasm composed of monomorphic polygonal or rounded cells arranged in compact acinar and trabecular structures (Fig. 5a, b). Immunohistochemical study revealed strong expression of pancytokeratin (KL-1) with variable expression of CK7 and diffuse strong cytoplasmic expression of trypsin (Fig. 5c), but lipase and amylase were negative. All other markers in the differential diagnosis were negative (CK5, CK20, HepPar-1, Synaptophysin, Chromogranin A, NSE, CD56, TTF1, ER, PR, protein S100, GATA3 and PAX8). These findings including in particular the strong and specific expression of trypsin confirmed the diagnosis of pancreatic-type ACC in the liver.

Histomorphology and immunohistochemistry of the liver tumor (from core biopsy). a core biopsy of the liver showing liver tissue adjacent to the acinar cell carcinoma, haematoxylin/eosin staining, 10-fold magnification. b compact acinar structures and trabeculae seen at higher magnification, haematoxylin/eosin staining, 40-fold magnification. c The tumor cells stained strongly for trypsin, 40-fold magnification

Autopsy confirmed several liver masses measuring up to six centimeters in size. There was no evidence of a salivary gland tumor or a primary pancreatic tumor. Additionally, review of the slides from the patient’s previous breast cancer confirmed a breast cancer of no special type and excluded the possibility of acinar-like differentiation. Thus, the previous breast cancer was also unrelated to the patient's ACC. Cause of her death was attributed to multiorgan failure due to severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Final diagnosis was pancreatic panniculitis due to primary pancreatic-type acinar cell carcinoma of the liver.

Taking into account the conspicuous accumulation of malignancies in our patient and her family, genetic analysis for familial atypical multiple mole-melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome was recommended to her relatives.

Review of literature

In addition to the presented case, 130 reports on pancreatic panniculitis were identified in the English literature between January 1994 and November 2014 by using the search terms “pancreatic panniculitis”, “subcutaneous fat necrosis AND pancreas” and “lipase hypersecretion syndrome” in PubMed and by checking results for appropriate cross-references.

Including the above case, all 131 cases (Table 1) were analyzed in respect to available data on age and gender of the patients, the underlying condition, additional symptoms, the sequence of the appearance of panniculitis and the diagnosis of the underlying disease, laboratory values and the outcome. The stated percentages refer to the respective number of cases including data on the analyzed parameter. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) using Student’s T-test or Fisher’s exact test where applicable. p < 0.05 was considered significant. Graphs were generated with SigmaPlot (Systat, San Jose, CA, USA).

Overall, 65 cases (49.6 %) were due to acute or chronic pancreatitis and 60 cases (45.8 %) had an underlying neoplastic condition. In six cases (4.6 %) other reasons were present, e.g. pancreas transplant rejection or pancreaticovascular fistula (Table 2).

Patients with pancreatic panniculitis had a mean age of 54.8 years. Yet, patients with neoplastic causes were significantly older than individuals with pancreatitis (Fig. 6a). 57.4 % of the patients were male with no difference in sex distribution between underlying pancreatitis and malignancy.

Comparison of patients with pancreatitis and neoplasm underlying pancreatic panniculitis (a-c): a Patients with neoplastic conditions are significantly older than patients with pancreatitis (66.0 +/− 13.0 years vs. 44.7 +/− 20.5 years, p < 0.001). b Underlying malignancy is diagnosed significantly later than underlying pancreatitis (134 +/− 135 days vs. 20 +/− 26 days, p < 0.001). c Tumor patients have significantly higher lipase levels than pancreatitis patients (16611 +/− 20772 vs. 5324 +/− 14436 U/l, p < 0.01). d Kaplan-Meier plot of survival after appearance of the first panniculitis lesion in patients with pancreatic panniculitis associated with malignancy. Median survival is 4.75 months (n = 29)

In 48.9 %, cutaneous lesions were noted prior to the diagnosis of the underlying disease. The mean duration from appearance of the first lesion to diagnosis was 85 days +/− 110 days (range: 2–540 days; median 42 days). This period was significantly longer when pancreatic panniculitis was due to a neoplasm than when a pancreatitis was present (Fig. 6b). Moreover, the portion of patients developing panniculitis before the diagnosis of the underlying condition was by trend higher in patients with neoplastic disease (66.7 %) than in patients with pancreatitis (48.3 %; p = 0.06).

A PPP syndrome with additional signs of arthritis was present in 49 cases (37.4 %).

One hundred twelve case reports (85.5 %) contained information on the serum levels of at least one pancreatic enzyme. In all but two of these reports (1.8 %) either amylase or lipase were elevated – in one of these two cases only amylase had been measured. The mean level of lipase was 11560 U/l +/− 19010 U/l (range 7–89700 U/l, median 3942.5 U/l). Again, patients with pancreatitis and neoplastic conditions differed markedly with tumor patients having significantly higher lipase levels (Fig. 6c). ROC analysis identified a lipase level of 4414 U/l as best cut-off value with higher values having a sensitivity of 73.0 % and a specificity of 82.1 % for the diagnosis of a neoplastic cause (AUC = 0.785, 95 % CI 0.68 to 0.89).

Only limited data was available concerning survival and follow-up. 12 patients with pancreatitis (21.4 %) died from complications. For underlying malignancy, follow-up data was available for 29 patients. A Kaplan-Meier plot of survival was computed, yielding a median survival of 4.75 months after appearance of the first skin lesion (Fig. 6d).

Discussion

Panniculitis is a clinical finding, which can be caused by various etiologic factors including infectious, immunologic and neoplastic conditions [19–21].

In our case, numerous causes could be excluded, while others were very unlikely: No infectious organism could be detected directly or indirectly. Continuous medication was unchanged and unsuspicious for causing erythema nodosum. Imaging had not yielded any evidence of malignancy other than the finally diagnosed ACC. Rheumatologic disease was judged unlikely based on consultation with a rheumatologist.

Therefore, regarding laboratory data and histologic results pancreatic panniculitis was the only possible diagnosis.

Our case of pancreatic panniculitis is noteworthy for two reasons: The absence of pancreatic disease and the extrapancreatic manifestation of pancreatic-type ACC. The combination of both has not been previously described in the literature. Pancreatic panniculitis without definite proof of pancreatic disease is found in four cases in the literature: Beltraminelli et al. [22] report a case of acinar cell cystadenocarcinoma of presumably pancreatic origin metastatic to the liver. However, clear evidence of a pancreatic primary tumor was absent on imaging. Freireich-Astmann et al. [23] describe the history of a patient with hepatic metastases of an adenocarcinoma of unknown primary. CT did not show any pancreatic lesion and immunohistochemistry was negative for CA19-9 and CK19. Aznar-Oroval et al. present a case of gastric adenocarcinoma with hepatic metastases in association with pancreatic panniculitis, but without clinical or radiologic findings of pancreatic disease [24]. And finally, Corazza et al. [25] report about a patient with multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and missing pancreatic lesions in CT.

However, in all cases, no autopsy for definite verification of the absence of pancreatic disease was performed. Amylase or lipase were elevated in each of the cases, but could not be explained by clinical, radiologic or histological findings in all but Beltraminelli et al.’s case. While existence of a primary hepatic acinar cell cystadenocarcinoma should have been discussed in this case, findings are inconclusive in the other three.

The HCC described by Corazza showed “trabecular structures and acinar aspects”, features suggestive of or consistent with ACC [15]. As immunohistochemistry is not reported, the possibility of a pancreatic-type ACC of the liver cannot be fully excluded in that case.

Primary extrapancreatic ACC is extremely rare and only six cases of ACC originating in the liver have been described to date [15, 26, 27]. Diagnosis of pancreatic-type ACC originating from the liver requires exclusion not only of an occult pancreatic primary, but also of primaries at other possible sites, such as breast [28] or salivary glands [29]. In our case, neither clinical nor radiological evidence for another primary was present, which was finally verified by autopsy findings. Moreover, re-analysis of the samples of the previously treated breast cancer excluded a hitherto undiscovered acinar cell carcinoma of the breast.

Because of the rarity of primary ACC of the liver, no typical pattern can be specified in the different imaging modalities up to now. So far, most of the cases described were initially misclassified as one of the most common primary liver malignancies, such as HCC or cholangiocellular carcinoma (CCC), due to their imaging appearance. Moreover, a recent study on imaging findings in pancreatic ACC also reported a high variability in several parameters analyzed [30]. Thus, a thorough histological work-up of specimens after a resection or core biopsy is required to ensure the correct diagnosis [15, 26, 27].

What could be objected to the diagnosis of an ACC of the liver in our case is the multifocality of the liver lesions, which is suggestive for metastatic disease. However, despite thorough work-up no other primary was found. Furthermore, it is worth noting that ACC is normally relatively large in size by the time of diagnosis [4], which makes an occult primary rather unlikely. In addition, multifocal growth of primary liver tumors is not unusual, e.g. in intrahepatic CCC [31, 32] and HCC [33, 34]. Indeed, primary hepatic ACC might originate from acinar trans-differentiation of biliary progenitor cells, thus representing the acinar counterpart of hepatic cholangiocarcinoma [15].

In an analysis of more than 130 cases of pancreatic panniculitis described in the last 20 years, we could show that nearly half of the cases are associated with an internal malignancy. Current concepts of the pathogenesis of pancreatic panniculitis suggest a role of pancreatic enzymes produced or released by these tumors [8, 9]. Therefore – though only rarely so named [35] – pancreatic panniculitis should be regarded as facultative paraneoplastic condition [36] and a tumor screening, especially for pancreatic tumors, should always be included in the diagnostic work-up.

The analysis of different parameters of these cases revealed significant differences between patients with pancreatic panniculitis and associated neoplasm or pancreatitis. On average, patients with a tumor are older and have higher lipase levels. Moreover, it takes longer until a diagnosis is made in these cases. A lipase cut-off value of 4414 U/l is able to differentiate between underlying pancreatitis and neoplasm with a sensitivity and specificity comparable with CA 19–9 in ductal adenocarcinoma vs. benign pancreatic disease [37].

Regarding the epidemiology and the natural course of malignancy and pancreatitis these results are not very surprising. However, these items can provide a first orientation, which etiology has to be primarily suspected. Like this, they may trigger a particularly intensive search for tumors in older patients with high lipase levels and a long-lasting history of panniculitis.

This is even more important as pancreatic panniculitis seems to be a hallmark of poor prognosis in tumor patients. Median survival in the cases with underlying malignancy and included follow-up data was 4.75 months after appearance of the first skin lesion.

Of course, this retrospective analysis has significant limitations as it is exclusively based on case reports. Though, it is the first systematic evaluation of survival in pancreatic panniculitis and poor outcome is remarkable, because over 50 % of the included cases were ACC patients, which otherwise have considerably better survival [38, 39].

Due to the rarity of the disease, clear therapeutic algorithms for ACC are missing. Since most of the cases present with distant metastases only a subset of patients qualifies for resection [39]. Therefore, cancer therapy is often limited to palliative approaches like chemotherapy or ablative treatment. As in our case, patients often suffer heavily from the pain caused by their skin lesions and analgetic therapy is frequently not sufficiently able to reduce pain [12, 14, 22, 40, 41]. Thus, palliative treatment strategies are very important for symptom control as well.

Octreotide has been reported to alleviate symptoms in some cases [42–44]. Chemotherapeutic agents reported to be used in patients with pancreatic panniculitis and underlying ACC include gemcitabine and the FOLFIRI regime [45, 46]. Furthermore, one case with resolution of panniculitis following metastasectomy [47] and one case with marked symptom reduction after transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) of hepatic metastases [48] are described in literature. Some success in the treatment of pancreatic ACC has been reported with the use of FOLFOX [49], FOLFIRINOX [50], cisplatin/etoposide [51] and gemcitabine in various combinations including erlotinib [52].

Conclusion

To our best knowledge, this is the first report of pancreatic panniculitis in a patient with primary ACC of the liver.

The possibility of pancreatic panniculitis should always be included in diagnostic considerations regarding panniculitic lesions. Therefore, a cutaneous biopsy should be obtained, pancreatic enzymes should be measured and abdominal imaging should be performed as early as possible. When diagnosed, pancreatic panniculitis has to be regarded as a facultative paraneoplastic syndrome and appropriate tumor screening or biopsy procedures have to be undertaken. This is especially important in older patients with high lipase levels and long-lasting symptoms. Regarding the presented case, tumors of extrapancreatic primary must also be considered.

Pancreatic-type ACC is the malignancy most often associated with pancreatic panniculitis. It can not only originate from the pancreas but also from the liver, which can be diagnosed, when other primary sites have been excluded.

Pancreatic panniculitis in association with malignancy seems to be linked with poor prognosis. Thus, early diagnosis is necessary to improve survival and ease symptoms, e.g. by resection or chemotherapy. Symptomatic therapy with octreotide seems worth trying. Further studies are required to define standard therapeutic strategies for unresectable ACC.

Consent

During her lifetime, the patient consented orally to the use of her patient history and all the related images and information for scientific purposes. After the patient’s death her daughter gave written consent for the publication of the case.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

acinar cell carcinoma

- ACE:

-

angiotensin-converting enzyme

- AFP:

-

alpha fetoprotein

- ANA:

-

anti-nuclear antibody

- ANCA:

-

anti-neutrophil cytoplasmatic antibody

- AP:

-

alkaline phosphatase

- AST:

-

aspartate transaminase

- CA 19–9:

-

carbohydrate antigen 19–9

- CCC:

-

cholangiocellular carcinoma

- CEA:

-

carcinoembryonic antigen

- CK:

-

cytokeratin

- CRP:

-

c-reactive protein

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- ECOG:

-

Eastern cooperative oncology group

- EN:

-

erythema nodosum

- ESWL:

-

extracorporal shock wave lithotripsy

- f:

-

female

- FOLFIRI:

-

folinic acid, 5-fluoruracil, irinotecan

- FOLFIRINOX:

-

folinic acid, 5-fluoruracil, irinotecan, oxaliplatin

- FOLFOX:

-

folinic acid, 5-fluoruracil, oxaliplatin

- GGT:

-

gamma glutamyl transferase

- HCC:

-

hepatocellular carcinoma

- IPMN:

-

intraductal papillar mucinous neoplasm

- m:

-

male

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- n.r.:

-

not reported

- NEC:

-

neuroendocrine carcinoma

- NSAID:

-

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PPP syndrome:

-

pancreatitis panniculitis polyarthritis syndrome

- TACE:

-

transarterial chemoembolization

References

Chiari H: Über die sogenannte Fettnekrose. Prag Med Wochenschr 1883;8:255–6.

Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, Dicken CH. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413–7.

Le Borgne J, Partensky C, Dupas B, Chavaillon A. Weber-Christian syndrome revealing intraductal papillary mucinous tumor of the pancreas. Pancreas. 1999;18:322–4.

Klimstra DS, Heffess CS, Oertel JE, Rosai J. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. A clinicopathologic study of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:815–37.

Rani M, Kaka A. Lobular Panniculitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:465–5.

Marsh RW, Hagler KT, Carag HR, Flowers FP. Pancreatic panniculitis. Eur J Surg Oncol J Eur Soc Surg Oncol Br Assoc Surg Oncol. 2005;31:1213–5.

Laureano A, Mestre T, Ricardo L, Rodrigues AM, Cardoso J. Pancreatic panniculitis - a cutaneous manifestation of acute pancreatitis. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2014;8:35–7.

Hu JC, Gutierrez MA. Pancreatic panniculitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:e72–4.

Dhawan SS, Jimenez-Acosta F, Poppiti RJ, Barkin JS. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatitis: histochemical and electron microscopic findings. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1025–8.

Berman B, Conteas C, Smith B, Leong S, Hornbeck L. Fatal pancreatitis presenting with subcutaneous fat necrosis. Evidence that lipase and amylase alone do not induce lipocyte necrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17(2 Pt 2):359–64.

Narváez J, Bianchi MM, Santo P, de la Fuente D, Ríos-Rodriguez V, Bolao F, Narváez JA, Nolla JM. Pancreatitis, Panniculitis, and Polyarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39:417–23.

Ashley SW, Lauwers GY. Case 37–2002. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1783–91.

Butturini G, Pisano M, Scarpa A, D’Onofrio M, Auriemma A, Bassi C. Aggressive approach to acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a single-institution experience and a literature review. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:363–9.

Martin SK, Agarwal G, Lynch GR. Subcutaneous fat necrosis as the presenting feature of a pancreatic carcinoma: the challenge of differentiating endocrine and acinar pancreatic neoplasms. Pancreas. 2009;38:219–22.

Agaimy A, Kaiser A, Becker K, Bräsen J-H, Wünsch PH, Adsay NV, Klöppel G. Pancreatic-type acinar cell carcinoma of the liver: a clinicopathologic study of four patients. Mod Pathol Off J U S Can Acad Pathol Inc. 2011;24:1620–6.

Lee H, Tang LH, Veras EF, Klimstra DS. The prevalence of pancreatic acinar differentiation in gastric adenocarcinoma: report of a case and immunohistochemical study of 111 additional cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:402–8.

Sun Y, Wasserman PG. Acinar cell carcinoma arising in the stomach: a case report with literature review. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:263–5.

Makhlouf HR, Almeida JL, Sobin LH. Carcinoma in jejunal pancreatic heterotopia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:707–11.

Requena L, Yus ES. Panniculitis. Part I. Mostly septal panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:163–83. quiz 184–186.

Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. Part II. Mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325–61. quiz 362–364.

Requena L, Requena C. Erythema nodosum. Dermatol Online J 2002, 8:4.

Beltraminelli HS, Buechner SA, Häusermann P. Pancreatic panniculitis in a patient with an acinar cell cystadenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Dermatol Basel Switz. 2004;208:265–7.

Freireich-Astman M, Segal R, Feinmesser M, David M. Pancreatic panniculitis as a sign of adenocarcinoma of unknown origin. Isr Med Assoc J IMAJ. 2005;7:474–5.

Aznar-Oroval E, Illueca-Ballester C, Sanmartín-Jiménez O, Martínez-Lapiedra C, Santos-Corés J. Paniculitis pancreática como forma de presentación inicial de adenocarcinoma gástrico con metástasis hepáticas. Rev Esp Patol. 2013;46:40–4.

Corazza M, Salmi R, Strumia R. Pancreatic Panniculitis as a First Sign of Liver Carcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2003;83:230–1.

Wildgruber M, Rummeny E-J, Gaa J. Primary acinar cell carcinoma of the liver. RöFo Fortschritte Auf Dem Geb Röntgenstrahlen Nukl. 2013;185:572–3.

Hervieu V, Lombard-Bohas C, Dumortier J, Boillot O, Scoazec J-Y. Primary acinar cell carcinoma of the liver. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:337–41.

Shingu K, Ito T, Kaneko G, Itoh N. Primary acinic cell carcinoma of the breast: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2013;2013:372947.

Sessa S, Ziranu A, Di Giacomo G, Giovanni A, Maccauro G. A rare case of iliac crest metastasis from acinic cell carcinoma of parotid gland. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:48.

Tian L, Lv X, Dong J, Zhou J, Zhang Y, Xi S, Zhang R, Xie C. Clinical features and imaging findings of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:14846–54.

Herber S, Otto G, Schneider J, Manzl N, Kummer I, Kanzler S, Schuchmann A, Thies J, Düber C, Pitton M. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for inoperable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:1156–65.

D’Onofrio M, Vecchiato F, Cantisani V, Barbi E, Passamonti M, Ricci P, Malagò R, Faccioli N, Zamboni G, Pozzi Mucelli R. Intrahepatic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma (IPCC): comparison between perfusion ultrasound and CT imaging. Radiol Med (Torino). 2008;113:76–86.

Goh BKP, Chow PKH, Teo J-Y, Wong J-S, Chan C-Y, Cheow P-C, Chung AYF, Ooi LLPJ. Number of nodules, Child-Pugh status, margin positivity, and microvascular invasion, but not tumor size, are prognostic factors of survival after liver resection for multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2014;18:1477–85.

Barman PM, Sharma P, Krishnamurthy V, Willatt J, McCurdy H, Moseley RH, Su GL. Predictors of mortality in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2821–5.

Ortega-Loayza AG, Ramos W, Gutierrez EL. Paz PC de, Bobbio L, Galarza C: Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancies in a tertiary health care hospital of a developing country. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:736–42.

McLean DI. Toward a definition of cutaneous paraneoplastic syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:11–3 [Cutaneous Paraneoplastic Syndromes].

Poruk K, Gay D, Brown K, Mulvihill J, Boucher K, Scaife C, Firpo M, Mulvihill S. The clinical utility of CA 19–9 in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: diagnostic and prognostic updates. Curr Mol Med. 2013;13:340–51.

Kitagami H, Kondo S, Hirano S, Kawakami H, Egawa S, Tanaka M. Acinar Cell Carcinoma of the Pancreas: Clinical Analysis of 115 Patients From Pancreatic Cancer Registry of Japan Pancreas Society. Pancreas. 2007;35:42–6.

Wisnoski NC, Townsend Jr CM, Nealon WH, Freeman JL, Riall TS. 672 patients with acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a population-based comparison to pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Surgery. 2008;144:141–8.

Borowicz J, Morrison M, Hogan D, Miller R. Subcutaneous fat necrosis/panniculitis and polyarthritis associated with acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a rare presentation of pancreatitis, panniculitis and polyarthritis syndrome. J Drugs Dermatol JDD. 2010;9:1145–50.

Berkovic D, Hallermann C. Carcinoma of the Pancreas with Neuroendocrine Differentiation and Nodular Panniculitis. Onkologie. 2003;26:473–6.

Bogart MM, Milliken MC, Patterson JW, Padgett JK. Pancreatic panniculitis associated with acinic cell adenocarcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2007;80:289–94.

Durden FM, Variyam E, Chren MM. Fat necrosis with features of erythema nodosum in a patient with metastatic pancreatic carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:39–41.

Hudson-Peacock MJ, Regnard CF, Farr PM. Liquefying panniculitis associated with acinous carcinoma of the pancreas responding to octreotide. J R Soc Med. 1994;87:361–2.

Antoine M, Khitrik-Palchuk M, Saif MW. Long-term survival in a patient with acinar cell carcinoma of pancreas. A case report and review of literature. JOP J Pancreas. 2007;8:783–9.

Iwatate M, Matsubayashi H, Sasaki K, Kishida N, Yoshikawa S, Ono H, Maitra A. Functional pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma extending into the main pancreatic duct and splenic vein. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:373–8.

Banfill KE, Oliphant TJ, Prasad KR. Resolution of pancreatic panniculitis following metastasectomy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:440–1.

Riediger C, Mayr M, Berger H, Becker K, Dobritz M, Kleeff J, Friess H. Transarterial chemoembolization of liver metastases as symptomatic therapy of lipase hypersecretion syndrome. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2012;30:e209–212.

Simon M, Bioulac-Sage P, Trillaud H, Blanc J-F. FOLFOX regimen in pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: Case report and review of the literature. Acta Oncol. 2011;51:403–5.

Schempf U, Sipos B, König C, Malek NP, Bitzer M, Plentz RR. FOLFIRINOX as first-line treatment for unresectable acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a case report. Z Für Gastroenterol. 2014;52:200–3.

Sorscher SM. Acinar Cell Carcinoma Responding to Carboplatin/Etoposide Chemotherapy. J Gastrointest Cancer 2011;43 Supplement 1:S2-3.

Lowery MA, Klimstra DS, Shia J, Yu KH, Allen PJ, Brennan MF, O’Reilly EM. Acinar Cell Carcinoma of the Pancreas: New Genetic and Treatment Insights into a Rare Malignancy. The Oncologist. 2011;16:1714–20.

Mahawish K, Iyasere IT. Pancreatic panniculitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2014. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204290.

Nishikawa Y, Sakuma Y, Yazumi S. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis-induced pancreatic panniculitis. Intern Med Tokyo Jpn. 2014;53:1715–6.

Holt BA, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. Hemosuccus pancreaticus caused by superior mesenteric artery fistula presenting as pancreatic panniculitis and anemia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2014;12:e97–98.

Makhoul E, Yazbeck C, Urbain D, Mana F, Mahanna S, Akiki B, Elias E. Pancreatic panniculitis: a rare complication of pancreatitis secondary to ERCP. Arab J Gastroenterol Off Publ Pan-Arab Assoc Gastroenterol. 2014;15:38–9.

Guo ZZ, Huang ZY, Huang LB, Tang CW. Pancreatic panniculitis in acute pancreatitis. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:327–30.

Sotoude H, Mozafari R, Mohebbi Z, Mirfazaelian H. Pancreatic panniculitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:944. e1–2.

Oh CC, Lee HY, Chan MFM, Thirumoorthy T. Pancreatic panniculitis following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Skinmed. 2013;11:173–4.

Rongioletti F, Caputo V. Pancreatic panniculitis. G Ital Dermatol E Venereol Organo Uff Soc Ital Dermatol E Sifilogr. 2013;148:419–25.

Gorovoy IR, McSorley J, Gorovoy JB. Pancreatic panniculitis secondary to acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Cutis. 2013;91:186–90.

Pfaundler N, Kessebohm K, Blum R, Stieger M, Stickel F. Adding pancreatic panniculitis to the panel of skin lesions associated with triple therapy of chronic hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2013;33:648–9.

Sharma M, Reddy DN, Kiat TC. Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography as a Risk Factor for Pancreatic Panniculitis in a Post-Liver Transplant Patient. ACG Case Rep J. 2014;2:36–8.

Burland L, Green BL. A cutaneous manifestation of intra-abdominal disease. BMJ. 2014;349:g5492–2.

Souza FH, Siqueira EBD, Mesquita L, Fabricio LZ, Tuon FF. Pancreatic panniculitis as the first manifestation of visceral disease--case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 Suppl 1):S125–128.

Colantonio S, Beecker J. Pancreatic panniculitis. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Medicale Can. 2012;184:E159.

Rose C, Leverkus M, Fleischer M, Shimanovich I. Histopathology of panniculitis--aspects of biopsy techniques and difficulties in diagnosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges J Ger Soc Dermatol JDDG. 2012;10:421–5.

Vasdev V, Bhakuni D, Narayanan K, Jain R. Intramedullary fat necrosis, polyarthritis and panniculitis with pancreatic tumor: a case report. Int J Rheum Dis. 2010;13:e74–78.

Jacobson-Dunlop E, Takiguchi R, White CR, White KP. Fatal pancreatitis presenting as pancreatic panniculitis without enzyme elevation. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:455–7.

Stauffer JA, Bray JM, Nakhleh RE, Bowers SP. Image of the month. Acinar cell carcinoma. Arch Surg Chic Ill 1960. 2011;146:1099–100.

Kirkland EB, Sachdev R, Kim J, Peng D. Early pancreatic panniculitis associated with HELLP syndrome and acute fatty liver of pregnancy. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:814–7.

Zheng ZJ, Gong J, Xiang GM, Mai G, Liu XB. Pancreatic panniculitis associated with acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a case report. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:225–8.

Lueangarun S, Sittinamsuwan P, Mahakkanukrauh B, Pattanaprichakul P, Pongprasobchai S. Pancreatic panniculitis: a cutaneous presentation as an initial clue to the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. J Med Assoc Thail Chotmaihet Thangphaet. 2011;94 Suppl 1:S253–257.

Qian D-H, Shen B-Y, Zhan X, Peng C, Cheng D. Liquefying panniculitis associated with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2:38.

Moro M, Moletta L, Blandamura S, Sperti C. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas associated with subcutaneous panniculitis. JOP J Pancreas. 2011;12:292–6.

Prikis M, Norman D, Rayhill S, Olyaei A, Troxell M, Mittalhenkle A. Preserved endocrine function in a pancreas transplant recipient with pancreatic panniculitis and antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transpl Surg. 2010;10:2717–22.

Gandhi RK, Bechtel M, Peters S, Zirwas M, Darabi K. Pancreatic panniculitis in a patient with BRCA2 mutation and metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1419–20.

Porcu A, Tilocca PL, Pilo L, Ruiu F, Dettori G. Pancreatic pseudocyst-inferior vena cava fistula causing caval stenosis, left renal vein thrombosis, subcutaneous fat necrosis, arthritis and dysfibrinogenemia. Ann Ital Chir. 2010;81:215–20.

Rao AG, Danturty I. Pancreatic panniculitis in a child. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:185–7.

Fraisse T, Boutet O, Tron A-M, Prieur E. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis syndrome: An unusual cause of destructive polyarthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:617–8.

Tran KT, Hughes S, Cockerell CJ, Yancey KB. Tender erythematous plaques on the legs. Pancreatic panniculitis (PP). Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:e65–66.

Harris MD, Bucobo JC, Buscaglia JM. Pancreatitis, panniculitis, polyarthritis syndrome successfully treated with EUS-guided cyst-gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:456–8.

Beyazıt H, Aydin O, Demirkesen C, Derin D, Süt P, Emre A, Mandel N. Pancreatic panniculitis as the first manifestation of the pancreatic involvement during the course of a gastric adenocarcinoma. Med Oncol Northwood Lond Engl. 2011;28:137–9.

Kuwatani M, Kawakami H, Yamada Y. Osteonecrosis and panniculitis as life-threatening signs. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2010;8:e52–53.

Chee C. Panniculitis in a patient presenting with a pancreatic tumour and polyarthritis: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2009;3:7331.

Chopra R, Chhabra S, Thami GP, Punia RPS. Panniculitis: clinical overlap and the significance of biopsy findings. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:49–58.

Farrant P, Abu-Nab Z, Hextall J. Tender erythematous nodules on the lower limb. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:549–51.

Madarasingha NP, Satgurunathan K, Fernando R. Pancreatic panniculitis: A rare form of panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

Chiewchengchol D, Wananukul S, Noppakun N. Pancreatic panniculitis caused by L-asparaginase induced acute pancreatitis in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:47–9.

Poelman SM, Nguyen K. Pancreatic panniculitis associated with acinar cell pancreatic carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:38–42.

Lakhani A, Maas L. Necrotizing panniculitis: a skin condition associated with acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. South Med J. 2008;101:554–5.

Sagi L, Amichai B, Barzilai A, Weitzen R, Trau H. Pancreatic panniculitis and carcinoma of the pancreas. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e205–207.

Lee WS, Kim MY, Kim SW, Paik CN, Kim HO, Park YM. Fatal Pancreatic Panniculitis Associated with Acute Pancreatitis: A Case Report. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:914–7.

Suwattee P, Cham PMH, Pope E, Ho N. Pancreatic panniculitis in a 4-year-old child with nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:659–60.

Bagazgoitia L, Alonso T, Ríos-Buceta L, Ruedas A, Carrillo R, Muñoz-Zato E. Pancreatic panniculitis: an atypical clinical presentation. Eur J Dermatol EJD. 2009;19:191–2.

Shehan JM, Kalaaji AN. Pancreatic panniculitis due to pancreatic carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:822.

Johnson MA, Kannan DG, Balachandar TG, Jeswanth S, Rajendran S, Surendran R. Acute septal panniculitis. A cutaneous marker of a very early stage of pancreatic panniculitis indicating acute pancreatitis. J Pancreas. 2005;6:334–8.

Gahr N, Technau K, Ghanem N. Intraductal papillary mucinous adenoma of the pancreas presenting with lobular panniculitis. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1397–8.

Price-Forbes AN, Filer A, Udeshi UL, Rai A. Progression of imaging in pancreatitis panniculitis polyarthritis (PPP) syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006;35:72–4.

Pike JL, Rice JC, Sanchez RL, Kelly EB, Kelly BC. Pancreatic panniculitis associated with allograft pancreatitis and rejection in a simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant recipient. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transpl Surg. 2006;6:2502–5.

Fernández-Jorge B, García-Silva J, Almagro M, Ruzo JS, Rey EC, Fonseca E. Pancreatic panniculitis after endoscopic retrograde pancreatography with sphincterotomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:463–4.

Kaufman HL, Harandi A, Watson MC, Carter EL, DeRaffele G, Shahid M, Fine RL. Panniculitis after vaccination against CEA and MUC1 in a patient with pancreatic cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:62–3.

Van der Zee J-A, van Hillegersberg R, Toonstra J, Gouma DJ. Subcutaneous nodules pointing towards pancreatic disease: pancreatic panniculitis. Dig Surg. 2004;21:275–6.

Menon P, Kulshreshta R. Pancreatitis with panniculitis and arthritis: a rare association. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:161–2.

Preiss JC, Faiss S, Loddenkemper C, Zeitz M, Duchmann R. Pancreatic panniculitis in an 88-year-old man with neuroendocrine carcinoma. Digestion. 2002;66:193–6.

Echeverría CM, Fortunato LP, Stengel FM, Laurini J, Díaz C. Pancreatic panniculitis in a kidney transplant recipient. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:751–3.

Mourad FH, Hannoush HM, Bahlawan M, Uthman I, Uthman S. Panniculitis and arthritis as the presenting manifestation of chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:259–61.

Wang M-C, Sung J-M, Chen F-F, Lee W-C, Huang J-J. Pancreatic Panniculitis in a Renal Transplant Recipient. Nephron. 2000;86:550–1.

Cutlan RT, Wesche WA, Jenkins JJ, Chesney TM. A fatal case of pancreatic panniculitis presenting in a young patient with systemic lupus. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:466–71.

Heykarts B, Anseeuw M, Degreef H. Panniculitis caused by acinous pancreatic carcinoma. Dermatol Basel Switz. 1999;198:182–3.

López A, García-Estañ J, Marras C, Castaño M, Rojas MJ, Garre C, Gómez J. Pancreatitis associated with pleural-mediastinal pseudocyst, panniculitis and polyarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 1998;17:335–9.

Brown R, Buckley R, Kelley M. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1997;15:3418–9.

Kuerer H, Shim H, Pertsemlidis D, Unger P. Functioning pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analyses. Am J Clin Oncol. 1997;20:101–7.

Zellman GL. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(2, Part 1):282–3.

Ball NJ, Adams SP, Marx LH, Enta T. Possible origin of pancreatic fat necrosis as a septal panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(2 Pt 2):362–4.

Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, Thompson JN, Hughes JM, Walters JR. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1835–7.

Martínez-Escribano JA, Pedro F, Sabater V, Quecedo E, Navarro V, Aliaga A. Acute exanthem and pancreatic panniculitis in a patient with primary HIV infection and haemophagocytic syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:804–7.

Sanchez MH, Fernandez RS, Gomez-Calcerrada MR. Single-nodule pancreatic panniculitis. Dermatol Basel Switz. 1996;193:269.

Feuer J, Spiera H, Phelps RG, Shim H. Panniculitis of pancreatic disease masquerading as systemic lupus erythematosus panniculitis. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:2170–2.

Francombe J, Kingsnorth AN, Tunn E. Panniculitis, arthritis and pancreatitis. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:680–3.

Rodriguez M, Lopez GL, Prieto P, Fernandez L, Willisch A, Arce M. Massive subcutaneous and intraosseous fat necrosis associated with pancreatitis. Natural evolution of the radiographic picture. Clin Rheumatol. 1997;16:199–203.

Cheng KS, Stansby G, Law N, Gardham R. Recurrent panniculitis as the first clinical manifestation of recurrent acute pancreatitis secondary to cholelithiasis. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:105P–6P.

Cevasco M, Rodriguez JR, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Clinical Challenges and Images in GI. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1054–433.

Sahani D, Prasad SR, Maher M, Warshaw AL, Hahn PF, Saini S. Functioning acinar cell pancreatic carcinoma: diagnosis on mangafodipir trisodium (Mn-DPDP)-enhanced MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:126–8.

Agarwal S, Nelson JE, Stevens SR, Gilliam AC. An unusual case of cutaneous pancreatic fat necrosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:16–8.

Omland SH, Ekenberg C, Henrik-Nielsen R, Friis-Møller A. Pancreatic panniculitis complicated by infection with Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum: A case report. IDCases. 2014;1:45–6.

Choi H-J, Kim K-J, Lee M-W, Choi J-H, Moon K-C, Koh J-K. Pancreatic carcinoma-associated subcutaneous fat necrosis improved by palliative surgery. J Dermatol. 2004;31:584–6.

Federman DG, McNiff JM, Kirsner RS. Pancreatic panniculitis. Wounds 2004;16:140-146.

Stanford AR, Mezebish DS, Cobb MW. Nodular fat necrosis associated with lupus-induced pancreatitis. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:856–8.

Hammar A-M, Sand J, Lumio J, Hirn M, Honkonen S, Tuominen L, Nordback I. Pancreatic pseudocystportal vein fistula manifests as residivating oligoarthritis, subcutaneous, bursal and osseal necrosis: a case report and review of literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:273–8.

Shbeeb MI, Duffy J, Bjornsson J, Ashby AM, Matteson EL. Subcutaneous fat necrosis and polyarthritis associated with pancreatic disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1922–5.

Carasso S, Oren I, Alroy G, Krivoy N. Disseminated fat necrosis with asymptomatic pancreatitis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci. 2000;319:68–72.

Jovanovic M, Golusin Z, Petrovic A, Vuckovic N, Brkic S, Sotirovic-Senicar S, Petrovic K. Lobular panniculitis: A manifestation of pancreatic tumor with fatal outcome. Arch Oncol. 2005;13:153–5.

Mehringer S, Vogt T, Jabusch H-C, Kroiβ M, Fürst A, Schölmerich J, Messmann H. Treatment of panniculitis in chronic pancreatitis by interventional endoscopy following extracorporeal lithotripsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:104–7.

Azar L, Chatterjee S, Schils J. Pancreatitis, polyarthritis and panniculitis syndrome. Jt Bone Spine Rev Rhum. 2014;81:184.

Tucker C, Owen C, Malone J, Callen J. Pancreatic panniculitis mimicking septic emboli in a 7-year-old boy with abdominal compartment syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:AB148.

Ahn BC, Lee J, Suh KJ, Chun KA, Sohn SK, Lee K, Kim CK. Intramedullary fat necrosis of multiple bones associated with pancreatitis. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 1998;39:1401–4.

Karasick D, Schweitzer ME. Case 4: intraosseous fat necrosis associated with pancreatitis. Radiology. 1998;209:521–4.

Kotilainen P, Saario R, Mattila K, Nylamo E, Aho H. Intraosseous fat necrosis simulating septic arthritis and osteomyelitis in a patient with chronic pancreatitis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1998;118:174–5.

L’Hirondel JL, Fournier L, Fretille A, Denizet D, Loyau G. Intraosseous fat necrosis and metaphyseal osteonecrosis in a patient with chronic pancreatitis: MR imaging and CT scanning. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1994;12:191–4.

Ohno Y, Le Pavoux A, Saeki H, Asahina A, Tamaki K. A case of subcutaneous nodular fat necrosis with lipase-secreting acinar cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:384–5.

Klimstra DS, Adsay NV. Acinar Cell Carcinoma of the Pancreas: A Case Associated With the Lipase Hypersecretion Syndrome. Pathol Case Rev. 2001;6:121–6.

Sielaff T. The telltale rash: a man with pretibial erythema. Minn Med. 2008;91:45–6.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU) within the funding programme Open Access Publishing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SZ, DS, MFN and DW were involved in the clinical treatment of the patient. RE, AA, AH and FK performed the histological and pathological diagnostic investigations. All authors contributed to interdisciplinary interpretation of clinical, radiological and pathological findings. SZ performed the statistical analyses and wrote the paper. All authors edited the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zundler, S., Erber, R., Agaimy, A. et al. Pancreatic panniculitis in a patient with pancreatic-type acinar cell carcinoma of the liver – case report and review of literature. BMC Cancer 16, 130 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2184-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2184-6