Abstract

Background

Sexual dysfunction is a prevalent, long-term complication of breast cancer and its treatment and can be treated effectively with face-to-face sexual counselling. However, relatively few women actually opt for face-to-face sex therapy, with many women indicating that it is too confronting. Internet-based interventions might be a less threatening and more acceptable approach, because of the convenience, accessibility and privacy it provides. Recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy of internet-based programs for improving sexual functioning in the general population. The objective of the current study is to investigate the efficacy of an internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) program in alleviating problems with sexuality and intimacy in women who have been treated for breast cancer.

Methods/design

In a multicenter, randomized controlled trial we are evaluating the efficacy of an internet-based CBT program in reducing problems with sexuality and intimacy in breast cancer survivors. Secondary outcomes include body image, marital functioning, psychological distress, menopausal symptoms, and health-related quality of life. We will recruit 160 breast cancer survivors (aged 18-65 years) with a formal DSM-IV diagnosis of sexual dysfunction from general and academic hospitals in the Netherlands. Women are randomized to either an intervention or waiting-list control group. Self-report questionnaires are completed by the intervention group at baseline (T0), ten weeks after start of therapy (T1), post-treatment (T2), 3 months post-treatment (T3), and 9 months post-treatment (T4). The control group completes questionnaires at T0, T1 and T2.

Discussion

There is a need for accessible and effective interventions for the treatment of sexual dysfunctions in breast cancer survivors. This study will provide evidence about the efficacy of an internet-based approach to delivering a CBT intervention targeted specifically at these sexual health issues. If proven to be effective, internet-based CBT for problems with sexuality and intimacy will be a welcome addition to the care offered to breast cancer survivors. Hopefully this therapy will lower the barrier to seeking help for these problems, resulting in improved quality of life after breast cancer.

Trial registration

The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02091765).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer among women in the Netherlands [1]. Improved breast cancer screening and treatment have resulted in increased survival rates [2]. Consequently, more interest and research has focused on the health-related quality of life (HRQL) of breast cancer survivors, including issues of sexuality and intimacy.

The prevalence rates for sexual dysfunctions as a result of breast cancer treatment vary between 30% and 100% [3-7]. Breast cancer survivors (BCS) experience worse sexual functioning compared to women without a history of cancer [8-10]. Frequently reported problems include decreased sexual desire (23-64%), decreased sexual arousal or vaginal lubrication (20-48%), anorgasmia (16-36%) and dyspareunia (35-38%) [3].

The different components of breast cancer treatment can all directly or indirectly affect sexual functioning [3]. Previous studies have shown that women who have received chemotherapy are at a higher risk of developing sexual dysfunctions than women who have not undergone this treatment [8,11-17], regardless of the type of surgery [14,18]. Chemotherapy can cause premature, abrupt menopause, leading to reduced sexual desire in some women [19]. It can also induce vaginal dryness and atrophy, which subsequently can affect sexual functioning [6,8,12,13,15,20]. Results with regard to endocrine treatment are somewhat mixed, but studies show that tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors can lead to sexual problems [21-27]. The evidence pertaining to the effect of surgery on sexual functioning is mixed [28-30], with some studies showing that women who undergo a mastectomy report more problems in sexual functioning than women who receive breast conserving therapy [28,31,32], while other studies have not found an association between type of surgery and sexual functioning [18,29]. More consistent is the finding that mastectomy more often results in compromised body image than does breast conserving treatment [4,13,28]. Other common complaints after breast cancer treatment are concerns about sexual attractiveness and femininity, fatigue, anxiety and depression, fear of loss of fertility, and overall decreased HRQL [3,18,33,34]. Emotional well-being and the quality of the partner-relationship can also be affected by the distress surrounding diagnosis and treatment [35-37]. Although the diagnosis and treatment of any type of cancer can cause problems in sexual functioning [3], breast cancer raises particular concerns because of the importance of the breast in feminine sexuality and the breast as a source of erotic pleasure and stimulation [33].

Sexual dysfunctions can be treated effectively with face-to-face forms of sex therapy [38-41]. Sex therapy typically comprises a flexible treatment program including a number of elements that can be tailored to the needs of individuals and couples. It typically involves behavioral components derived from the sex therapy developed by Masters and Johnson [42], i.e. psycho-education about sexuality and sexual dysfunction, a temporary ban on intercourse, and sensate focus exercises. A ban on intercourse can break the vicious cycle of fear of sexual intercourse and subsequent negative experience and disappointment, and offers the opportunity for positive experiences by eliminating or reducing performance demand [43]. Sensate focus exercises form a hierarchically structured exercise program, through which partners gradually reintroduce the consecutive phases of sexual contact. The exercises are targeted at becoming more comfortable with one’s own body and achieving sexual intimacy with one’s partner, both physically and emotionally. Other goals are to discover new approaches to sexual stimulation, and to encourage communication between partners about sexual experiences, sexual desires and sexual boundaries. These behavioral elements of sex therapy are usually combined with cognitive therapy [40,43]. Through cognitive therapy, therapist and client aim to detect and modify the client’s dysfunctional, disturbing cognitions regarding sexuality that arise during exercises. Via the method of cognitive restructuring, the dysfunctional cognitions are replaced by more functional appraisals. Sex therapy is often delivered in a couple format, but individual applications and group therapy formats are also described in the literature [44,45].

The efficacy of different types of face-to-face therapy for female sexual dysfunction (FSD) has been demonstrated, including sexual desire and sexual arousal disorder [40,46,47], orgasmic disorder [48,49], sexual pain [50,51], and vaginismus [52,53]. Several modified treatment programs have been developed and evaluated for breast cancer survivors [44,54]. Interventions with stronger effects tend to be couple-focused and include treatment components that educate both partners about the woman’s diagnosis and treatment, promote couples’ mutual coping and support processes, and include treatment components that make use of specific sex therapy techniques addressing sexual and body image concerns [44,54].

Despite the availability of effective treatments for sexual dysfunctions, there is a significant discrepancy between the self-reported need for professional sexual health care in cancer survivors and the actual uptake of care [5,55]. Kedde et al. [5] reported that only 40% of BCS who felt a need for care actually consulted a health professional. Hill et al. [55] reported that, although over 40% of gynaecologic cancer and breast cancer survivors expressed interest in receiving professional care, only 7% had ever actually sought such care.

Although sexual functioning is an important issue, health care professionals may be reluctant to query breast cancer patients about sexual problems during medical consultations, due to time constraints, embarrassment, lack of knowledge and experience in this area, and/or lack of resources to provide support if needed [56,57]. It may also be difficult for patients to initiate discussion about their sexual difficulties with their health care professional [58-60]. It has been suggested that when reporting sensitive or potentially stigmatizing information, individuals may feel more comfortable undergoing assessment and treatment via the internet [61,62]. This idea is supported by a survey [de Blok G. Thesis on the outpatient clinic for sexuality and breast cancer of The Netherlands Cancer Institute. Unpublished manuscript] that was conducted in women who attended an informational meeting of a sexuality and breast cancer clinic, but who subsequently did not follow-up for an appointment for face-to-face counselling. While some women indicated that they did not consider treatment of their sexual problems to be necessary, others indicated that they did not wish to undergo such treatment in a hospital-setting, or that the face-to-face setting of the counselling formed too great a barrier. Many respondents suggested that internet-based therapy would be a less threatening and more acceptable approach. The advantages of internet-based therapy include privacy, convenience and accessibility [63-65], all of which may be particularly attractive in the area of sexual problems.

There is growing evidence that internet-based CBT is an effective method to treat a range of psychosocial problems [66-73]. More recently, internet-based CBT programs for sexual dysfunctions have been developed and tested [45,65,74-77]. However, most of these online interventions have focused on male sexual dysfunctions [74,75,77-80]. Early trials have demonstrated the applicability and effectiveness of online CBT for FSD in the general population [76], and of an online intervention for sexual problems in breast cancer survivors [81]. However, the efficacy of an internet-based CBT for sexual problems in BCS has not yet been researched.

In this article, we describe the design of a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial that evaluates the efficacy of an internet-based CBT program for sexual dysfunctions in women who have been treated for breast cancer. We hypothesize that women in the internet-based CBT group will report a significantly greater improvement in sexual functioning and intimacy than women in a waiting-list control group. Secondarily, we hypothesize that women who undergo the internet-based CBT will report significantly less psychological distress and fewer menopausal symptoms, and a significantly greater improvement in body image, marital functioning and HRQL than women in the control group.

Methods

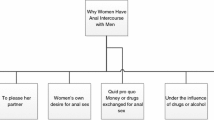

In this study, patients are randomized to either an intervention group or a waiting-list control group. Women in the intervention group will undergo an internet-based CBT aimed at alleviating problems with sexuality and intimacy. The design of the trial and the anticipated flow of participants are displayed in Figure 1. The trial has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Netherlands Cancer Institute (under number NL44153.031.13), as well as by all review boards of the hospitals from which patients are being recruited (for a list of the participating hospitals, see the Acknowledgements section). Patient recruitment and data collection started in September, 2013.

Study sample

The study sample will be composed of 160 women fulfilling the following inclusion criteria: (1) age 18-65 years (the upper limit of 65 years is not based on any assumption regarding the salience of sexuality with increasing age, but on the smaller chance of access to internet in this age group); (2) a history of histologically confirmed breast cancer (stages: T1-T4, N0-N1 and M0); (3) a diagnosis of breast cancer six months to five years prior to study entry; (4) completion of breast cancer treatment (with the exception of endocrine therapy and immunotherapy); (5) disease-free at time of study entry; (6) a basic fluency in the Dutch language (for assessment and therapy purposes); and (7) a formal diagnosis of sexual dysfunction according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV [82] (to be established by an experienced sexologist during an intake interview). Single as well as partnered women can participate in the study. Sexual orientation is irrelevant for eligibility.

Exclusion criteria are: (1) no access to internet; (2) serious cognitive or psychiatric problems (i.e., depression, alcohol dependency, or psychotic disorders) as determined on the basis of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview [83]; (3) treatment for another type of cancer (with the exception of cervix carcinoma in situ and basal cell carcinoma); (4) presence of severe relationship problems for which the internet-based program is not appropriate; (5) participation in a concurrent therapy program to alleviate problems with sexuality or intimacy; (6) participation in a concurrent CBT program for other psychological problems; and (7) participation in another trial investigating problems with sexuality/intimacy.

Recruitment and randomization

Patients are recruited from 10 community and university hospitals in the Netherlands and are identified through the hospital registries by their physician, or by means of the database of the Netherlands Cancer Registry. Selected patients are sent an invitation letter describing the study and internet-based therapy, and are asked to return a response card to indicate if they are interested in participation. In case of no interest, women are asked to specify their reason(s) for this on the card. In the absence of a response, a reminder is sent three weeks after the first mailing. Women who are not interested in participation or who do not respond to the reminder are not contacted again.

Interested women are screened for eligibility twice: first by a member of the study staff and subsequently by a sexologist. In these interviews, more information about the study procedures and therapy is given and eligibility criteria are checked. The sexologist carries out a diagnostic interview to determine final eligibility of the woman, and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview [83] is completed. All sexologists involved in the study are female, and have undergone special training in the application of the internet-based CBT program.

Eligible women are sent a baseline questionnaire (T0) and an informed consent form. Study questionnaires can be completed online or in a paper-and-pencil format. The baseline questionnaire assesses sociodemographic and medical background variables, and the study outcomes. If the score of the marital adjustment subscale of the Maudsley Marital Questionnaire [84] (see ‘Study measures’ section) exceeds the cut-off score of 35, the eligibility of the participant is discussed once more with the sexologists to determine if the nature and severity of the relationship problems would recommend treating these problems prior to tackling the sexual dysfunction, thus resulting in exclusion from study participation.

Consenting women are randomized to either an intervention group (n = 80) or a waiting-list control group (n = 80) using the minimization technique, with type of surgery (breast conserving therapy; mastectomy only; mastectomy with breast reconstructive surgery), current endocrine treatment for breast cancer (yes; no), time since breast cancer diagnosis (<1 year; 1-3 yrs; 3-5 yrs), and menopausal status (premenopausal; postmenopausal) as stratification variables.

Study arms

Intervention group: internet-based CBT program

Each woman is assigned a sexologist who guides her through the internet-based CBT program. Contact with the therapist is web-based, via a secured, password-protected website. From a total of 10 modules, the sexologist selects four to five modules that best fit the sexual problems of the client. The internet-based CBT program was originally developed for use in the general population at Virenze, a mental health center located in Utrecht, the Netherlands. The program was adapted for use specifically for breast cancer survivors. This involved editing and adding text related to the physical and psychosexual problems often experienced by women who have had breast cancer. The therapists are licensed psychologists and sexologists who have undergone additional training in issues relating to breast cancer, and in the use of the internet program.

A description of the content of the different program modules is provided in Table 1. Each module contains several interventions, each of which comprises the following elements: (1) introduction, (2) psycho-education, (3) “homework” assignments (e.g., registration exercises; discuss intimacy with partner; sensate focus exercises) and (4) reporting back to the therapist and receiving feedback on the homework assignments. The modules can be used in varying order, leading to a tailored and flexible treatment program consisting of a maximum of 20 therapy sessions that are completed within a period of 24 weeks. A minimum of five sessions is considered the lower limit of sessions required in order to expect an effect. The average time investment for a participant is 90-120 minutes per week. Women are motivated by the sexologist to involve their partner in the treatment, but partner involvement is not mandatory. The time limit within which the therapist should respond to incoming messages from a client is set at five working days. Weekly contact between therapist and client is pursued. After 10 weeks of treatment, a mid-term evaluation is held to reflect on the progress so far, and to adjust goals, if necessary, for the remaining part of treatment. The internet-based CBT program is provided at no cost to the woman.

Waiting-list control group

Participants in the control group are asked to refrain from undergoing any psychological or medical interventions for sexual problems during their participation in the study. To increase the likelihood that women will remain in the study until they are offered the CBT program, they are provided with a booklet addressing questions about sexuality and cancer. Additionally, six weeks after randomization and upon completion of the second questionnaire, women in the control group are contacted by telephone to address any questions or comments that they may have about their participation in the study, and to reconfirm that they will be eligible for the internet-based CBT program upon their completion of the study.

Data collection

Patients

Patients in both study arms complete a battery of self-report questionnaires at equivalent moments in time for the first three assessments (T0: baseline; T1: 10 weeks after start of therapy (intervention group) or 13 weeks after randomization (control group); and T2: post-treatment (intervention group) or 23 weeks after randomization (control group), see Figure 1). To achieve an equivalent average assessment time for both groups, women in the intervention group complete T2 post-treatment, but always between 20 and 24 weeks after start of therapy. Women who finish the CBT prior to 20 weeks complete T2 20 weeks after start of therapy. Women in the intervention group also complete questionnaires three months post-treatment (T3) and nine months post-treatment (T4). The control group is not asked to complete T3 or T4, but rather is given the opportunity to undergo the intervention following completion of T2. This was done because it was not deemed ethically acceptable to withhold the intervention from women in the control group for the prolonged period of time that would be required if they were to complete all follow-up questionnaires (i.e., approximately one year after study enrollment). To minimize respondent burden, the T4 questionnaire only includes the questionnaires assessing the primary outcome measures. In every questionnaire, women in both the intervention group and control group are asked if they pursued any other activities to reduce their sexual problems (e.g., use of vaginal lubricant, relaxation exercises). A reminder is sent to participants who do not complete and return the questionnaire within one week. If a woman does not complete the questionnaire in the week after the reminder, she is contacted by telephone.

Partners

Only partners of the women in the intervention group are asked to complete questionnaires regarding problems with sexuality and intimacy (male partner: IIEF [85], female partner: FSFI [86]), and relational functioning (PAIR Inventory [87], MMQ [84]) at the same points in time as the participants.

Study measures

Sociodemographic and clinical data

Sociodemographic data and clinical data are obtained during the screening interview and via the baseline questionnaire. Sociodemographic data include age, education, relational status, living situation and work status. Clinical data are collected from the medical records and via self-report, and include date of breast cancer diagnosis, treatment (type of surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, endocrine therapy, immunotherapy), medication use and comorbidity.

Outcome measures

Detailed descriptions of the outcome measures are provided in Table 2. Briefly, the primary outcome measures include standardized self-report questionnaires assessing problems with sexuality and intimacy. These include the Sexual Activity Questionnaire [88,89], the Female Sexual Function Index [86,90], the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised [91] and the PAIR Inventory [87]. Secondary outcome measures include standardized self-report questionnaires assessing body image (EORTC QLQ-BR 23 Body image subscale [92]), menopausal symptoms (FACT-ES ESS-18 [93]), marital functioning (MMQ [84]), psychological distress (HADS [94,95]) and HRQL (SF-36 [96,97]). The International Index of Erectile Function [85] is used to assess sexual functioning in male partners.

Compliance with the internet-based CBT program

The level of compliance is established via a question that is posed to the sexologist at the completion of therapy: ‘How many of the total number of therapy sessions that you considered to be optimal for this client has the client actually completed?’. This question is answered on a five-point scale, ranging from ‘the client has done all of the sessions I deemed necessary (100%)’ to ‘the client has not/barely done the sessions I deemed necessary (less than 25%)’. Additionally, the actual number of completed modules and interventions are extracted from the client’s records at the mental health center where the internet program is housed. Additionally, at completion of therapy, both the client and the sexologist are asked to indicate the frequency with which homework assignments were completed on a five-point scale (always-frequently-occasionally-rarely-never), and to indicate the reasons for not completing all homework assignments, if applicable. Women who do not complete the internet-based CBT program are asked to indicate their reason(s) for discontinuation (e.g., therapy was too intensive, online therapy was not suitable, illness). Every effort will be made to obtain all questionnaires of all participants, regardless of whether they do or do not complete their therapy.

Patients’ evaluation of the intervention program

Upon completion of the CBT, women in the intervention group are asked to complete an evaluation questionnaire about the program. Questions are posed about their satisfaction with the program, the perceived efficacy of the program in alleviating sexual problems, their satisfaction with the choice of modules and exercises, the usability of the program, if they would recommend the treatment to other women experiencing similar problems, and if they would suggest any changes to the program. Women who discontinue the CBT program are asked the same questions.

A subset of women (approximately 15 from the intervention group) will be asked to participate in an evaluation interview by telephone. This semi-structured interview covers the same topic areas as addressed by the self-report evaluation questionnaire, allowing women to provide feedback in a more narrative form. Where applicable, women will also be asked if their partner would be willing to share his or her experience with the program.

Statistical issues

Power calculation

The SAQ, FSFI, FSDS-R and PAIR Inventory are the primary outcome measures on which sample size calculations are based. With a total sample of 130 women (65 per group), and under the assumption of no interaction, the study will have a 80% power to detect a 0.5 standard deviation difference (Cohen’s effect size [98]) for the main effects of the internet-based CBT program, with the p-value set at 0.05 (two-sided test). A 0.5 standard deviation difference is considered to be indicative of clinically meaningful differences in self-reported symptom experience [98].

We will recruit 160 women into the study, to allow for an attrition rate of approximately 20% (i.e., women who discontinue participation in the study entirely, including failure to complete all follow-up questionnaires). Those women who discontinue the therapy but complete the follow-up assessments will be included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

Statistical analysis

First, student’s t-tests or appropriate non-parametric statistics will be used to evaluate the comparability of the intervention and control group at baseline in terms of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. If, despite the stratified randomization procedure, the groups are not comparable on one or more background variables, those variables will be employed routinely as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Questionnaire scores will be calculated according to published scoring algorithms. Between-group differences over time in mean scores will be tested using multilevel analysis. Effect sizes will be calculated using standard statistical procedures. All analyses will, to as great an extent as possible, be conducted on an intention-to-treat basis. Per protocol analyses will also be carried out (as a secondary analysis), comparing women who meet minimal compliance levels with the program with the control group. We will use correlation analyses to examine the relationship between degree of program adherence, partner involvement, and program effect. For the analysis of the secondary outcome measures, appropriate statistical (p value) adjustments will be made for multiple testing. The semi-structured interview data will be transcribed and content analyzed to extract narrative, qualitative information about the women’s experience with the intervention.

Discussion

A relatively large percentage of breast cancer survivors experience sexual problems as a consequence of their disease and its treatment. Studies show that CBT is an effective treatment method for alleviating sexual dysfunctions in the general population, when provided in a face-to-face setting. Recently, more attention has been paid to developing internet-based interventions targeting sexual functioning. However, research into internet-based interventions for FSDs is scarce, and even less is known about the efficacy of internet-based CBT specifically targeted at breast cancer survivors. In the current trial, we are investigating the efficacy of an internet-based CBT in reducing problems with sexuality and intimacy, psychological distress and menopausal symptoms, and in improving body image, marital functioning and health-related quality of life of breast cancer survivors.

This trial has several notable strengths, including: (1) the randomized trial design, (2) the multicenter nature of the trial, (3) the comparison of the intervention group with a waiting-list control group, (4) the use of intention-to-treat analyses, and (5) the long-term follow-up assessments of outcomes in women in the intervention group.

This trial also has several limitations. First, it would be valuable to compare the internet-based CBT group not only with a control group, but also with a face-to-face CBT group. However, our previous experience in offering breast cancer survivors the opportunity to participate in face-to-face sexual therapy proved problematic [de Blok G. Thesis on the outpatient clinic for sexuality and breast cancer of The Netherlands Cancer Institute. Unpublished manuscript]. Very few women were willing to take that step, indicating that they found the face-to-face setting too confronting. Thus, we anticipated that including a face-to-face therapy arm in the trial would result in substantial recruitment problems. Also, we consider it important to first establish the efficacy of the internet-based CBT program. If the program proves to be efficacious, a subsequent step could be a comparative effectiveness study with face-to-face treatment [61]. Second, although as one of the conditions for participating in the trial, women are asked not to participate in any other programs targeted at their sexual problems, the possibility exists that some women (particularly in the control group) may do so. However, we do not expect any such activities to be as structured, tailored and targeted at sexual problems specifically after breast cancer treatment as our CBT program. In any case, at each assessment point, women are asked to report any activities that they may have undertaken to alleviate their sexual problems. Third, the absence of T3 and T4 follow-up assessments for the control group precludes a longer-term between-group comparison of study outcomes. As noted earlier, this decision was based on both ethical and feasibility considerations. We (and the institutional review board) did not consider it appropriate to withhold therapy for an extended period of time, which would have been the case if women in the control group were required to complete all assessment points before having the opportunity to participate in the internet-based CBT program. We also believed that such a long waiting list period would have a significant, negative effect on recruitment into the study.

In conclusion, given the high rates of sexual dysfunction in breast cancer survivors, there is a need for effective and accessible treatments for these problems. If proven to be effective, internet-based CBT can be a valuable addition to the standard care offered to breast cancer survivors. Hopefully, this treatment will lower the barrier to seeking help, resulting in an improved quality of life after treatment of breast cancer.

References

Netherlands Cancer Registry: [http://www.cijfersoverkanker.nl].

Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, Butler J, Rachet B, Maringe C, et al. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995-2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet. 2011;377(9760):127–38.

Sadovsky R, Basson R, Krychman M, Morales AM, Schover L, Wang R, et al. Cancer and sexual problems. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 Pt 2):349–73.

Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang S, D’Onofrio C, Banks PJ, Bloom JR. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15(7):579–94.

Kedde H, van de Wiel HB, Weijmar Schultz WC, Wijsen C. Sexual dysfunction in young women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(1):271–80.

Bloom JR, Stewart SL, Chang S, Banks PJ. Then and now: quality of life of young breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13(3):147–60.

Krychman ML, Pereira L, Carter J, Amsterdam A. Sexual oncology: sexual health issues in women with cancer. Oncology. 2006;71(1-2):18–25.

Broeckel JA, Thors CL, Jacobsen PB, Small M, Cox CE. Sexual functioning in long-term breast cancer survivors treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;75(3):241–8.

Bredart A, Dolbeault S, Savignoni A, Besancenet C, This P, Giami A, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of sexual problems after early-stage breast cancer treatment: results of a French exploratory survey. Psychooncology. 2011;20(8):841–50.

Dorval M, Maunsell E, Deschênes L, Brisson J, Mâsse B. Long-term quality of life after breast cancer: comparison of 8-year survivors with population controls. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(2):487–94.

Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, Kahn B, Bower JE. Breast cancer in younger women: reproductive and late health effects of treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(22):4184–93.

Burwell SR, Case LD, Kaelin C, Avis NE. Sexual problems in younger women after breast cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2815–21.

Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, Meyerowitz BE, Wyatt GE. Life after breast cancer: understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(2):501–14.

Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, Krupnick JL, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Quality of life at the end of primary treatment of breast cancer: first results from the moving beyond cancer randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(5):376–87.

Rosenberg SM, Tamimi RM, Gelber S, Ruddy KJ, Bober SL, Kereakoglow S, et al. Treatment-related amenorrhea and sexual functioning in young breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2014;120(15):2264–71.

Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Psychosocial problems among younger women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13(5):295–308.

Alder J, Zanetti R, Wight E, Urech C, Fink N, Bitzer J. Sexual dysfunction after premenopausal stage I and II breast cancer: do androgens play a role? J Sex Med. 2008;5(8):1898–906.

Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Belin TR, Meyerowitz BE, Rowland JH. Predictors of sexual health in women after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(8):2371–80.

Ochsenkuhn R, Hermelink K, Clayton AH, von Schonfeldt V, Gallwas J, Ditsch N, et al. Menopausal status in breast cancer patients with past chemotherapy determines long-term hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2011;8(5):1486–94.

Cavalheiro JA, Bittelbrunn A, Menke CH, Biazus JV, Xavier NL, Cericatto R, et al. Sexual function and chemotherapy in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. BMC Womens Health. 2012;12:28.

Baumgart J, Nilsson K, Evers AS, Kallak TK, Poromaa IS. Sexual dysfunction in women on adjuvant endocrine therapy after breast cancer. Menopause. 2013;20(2):162–8.

Berglund G, Nystedt M, Bolund C, Sjoden PO, Rutquist LE. Effect of endocrine treatment on sexuality in premenopausal breast cancer patients: a prospective randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2788–96.

Panjari M, Bell RJ, Davis SR. Sexual function after breast cancer. J Sex Med. 2011;8(1):294–302.

Frechette D, Paquet L, Verma S, Clemons M, Wheatley-Price P, Gertler S, et al. The impact of endocrine therapy on sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women with early stage breast cancer: encouraging results from a prospective study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;141(1):111–7.

Buijs C, de Vries EG, Mourits MJ, Willemse PH. The influence of endocrine treatments for breast cancer on health-related quality of life. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34(7):640–55.

Schover LR, Baum GP, Fuson LA, Brewster A, Melhem-Bertrandt A. Sexual Problems During the First 2 Years of Adjuvant Treatment with Aromatase Inhibitors. J Sex Med. 2014;11(12):3102–11.

Mok K, Juraskova I, Friedlander M. The impact of aromatase inhibitors on sexual functioning: current knowledge and future research directions. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2008;17(5):436–40.

Markopoulos C, Tsaroucha AK, Kouskos E, Mantas D, Antonopoulou Z, Karvelis S. Impact of breast cancer surgery on the self-esteem and sexual life of female patients. J Int Med Res. 2009;37(1):182–8.

Schover LR, Yetman RJ, Tuason LJ, Meisler E, Esselstyn CB, Hermann RE, et al. Partial mastectomy and breast reconstruction. A comparison of their effects on psychosocial adjustment, body image, and sexuality. Cancer. 1995;75(1):54–64.

Greendale GA, Petersen L, Zibecchi L, Ganz PA. Factors related to sexual function in postmenopausal women with a history of breast cancer. Menopause. 2001;8(2):111–9.

Aerts L, Christiaens MR, Enzlin P, Neven P, Amant F. Sexual functioning in women after mastectomy versus breast conserving therapy for early-stage breast cancer: A prospective controlled study. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2014;23(5):629–36.

Rowland JH, Desmond KA, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR, Wyatt GE, Ganz PA. Role of breast reconstructive surgery in physical and emotional outcomes among breast cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(17):1422–9.

Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J. Sexuality after breast cancer: a review. Maturitas. 2010;66(4):397–407.

Speer JJ, Hillenberg B, Sugrue DP, Blacker C, Kresge CL, Decker VB, et al. Study of sexual functioning determinants in breast cancer survivors. Breast J. 2005;11(6):440–7.

Baucom DH, Porter LS, Kirby JS, Gremore TM, Wiesenthal N, Aldridge W, et al. A couple-based intervention for female breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(3):276–83.

Hawkins Y, Ussher J, Gilbert E, Perz J, Sandoval M, Sundquist K. Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer: the experience of partners in a sexual relationship with a person with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(4):271–80.

Northouse LL, Templin T, Mood D, Oberst M. Couples’ adjustment to breast cancer and benign breast disease: a longitudinal analysis. Psychooncology. 1998;7(1):37–48.

Günzler C, Berner MM. Efficacy of Psychosocial Interventions in Men and Women With Sexual Dysfunctions—A Systematic Review of Controlled Clinical Trials. J Sex Med. 2012;9(12):3108–25.

Heiman JR, Meston CM. Empirically validated treatment for sexual dysfunction. Annu Rev Sex Res. 1997;8:148–94.

ter Kuile MM, Both S, van Lankveld JJ. Cognitive behavioral therapy for sexual dysfunctions in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33(3):595–610.

van Lankveld JJDM, ter Kuile MM, Leusink P. Seksuele disfuncties: Diagnostiek en behandeling. Houten: Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum; 2010.

Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston: Little, Brown; 1970.

van Lankveld JJDM, Broomans E. Cognitieve therapie bij seksuele disfuncties. In: Bögels SM, van Oppen P, editors. Cognitieve therapie: theorie en praktijk. 2nd ed. Houten: Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum; 2011. p. 391–424.

Scott JL, Kayser K. A review of couple-based interventions for enhancing women’s sexual adjustment and body image after cancer. Cancer J. 2009;15(1):48–56.

Hucker A, McCabe MP. Incorporating Mindfulness and Chat Groups Into an Online Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Mixed Female Sexual Problems. J Sex Res. 2014;17:1–13.

Trudel G, Marchand A, Ravart M, Aubin S, Turgeon L, Fortier P. The effect of a cognitive-behavioral group treatment program on hypoactive sexual desire in women. Sex Relation Ther. 2001;16(2):145–64.

Hurlbert DF. A comparative study using orgasm consistency training in the treatment of women reporting hypoactive sexual desire. J Sex Marital Ther. 1993;19(1):41–55.

Spence SH. Group versus individual treatment of primary and secondary female orgasmic dysfunction. Behav Res Ther. 1985;23(5):539–48.

Morokoff PJ, LoPiccolo J. A comparative evaluation of minimal therapist contact and 15-session treatment for female orgasmic dysfunction. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54(3):294–300.

Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalife S, Pagidas K, Glazer HI, Meana M, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive–behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain. 2001;91(3):297–306.

Masheb RM, Kerns RD, Lozano C, Minkin MJ, Richman S. A randomized clinical trial for women with vulvodynia: Cognitive-behavioral therapy vs. supportive psychotherapy. Pain. 2009;141(1-2):31–40.

ter Kuile MM, Bulte I, Weijenborg PT, Beekman A, Melles R, Onghena P. Therapist-aided exposure for women with lifelong vaginismus: a replicated single-case design. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(1):149–59.

ter Kuile MM, Melles R, de Groot HE, Tuijnman-Raasveld CC, van Lankveld JJ. Therapist-aided exposure for women with lifelong vaginismus: a randomized waiting-list control trial of efficacy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(6):1127–36.

Taylor S, Harley C, Ziegler L, Brown J, Velikova G. Interventions for sexual problems following treatment for breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130(3):711–24.

Hill EK, Sandbo S, Abramsohn E, Makelarski J, Wroblewski K, Wenrich ER, et al. Assessing gynecologic and breast cancer survivors’ sexual health care needs. Cancer. 2011;117(12):2643–51.

Stead ML, Brown JM, Fallowfield L, Selby P. Lack of communication between healthcare professionals and women with ovarian cancer about sexual issues. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(5):666–71.

Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E, Wong WK, Mason C, Hobbs K, et al. Talking about sex after cancer: a discourse analytic study of health care professional accounts of sexual communication with patients. Psychol Health. 2013;28(12):1370–90.

Flynn KE, Reese JB, Jeffery DD, Abernethy AP, Lin L, Shelby RA, et al. Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21(6):594–601.

Hordern AJ, Street AF. Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust. 2007;186(5):224–7.

Halley MC, May SG, Rendle KA, Frosch DL, Kurian AW. Beyond barriers: fundamental ‘disconnects’ underlying the treatment of breast cancer patients’ sexual health. Cult Health Sex. 2014;16(9):1169–80.

Ritterband LM, Gonder-Frederick LA, Cox DJ, Clifton AD, West RW, Borowitz SM. Internet interventions: In review, in use, and into the future. Prof Psychol: Res Pract. 2003;34(5):527–34.

Taylor CB, Luce KH. Computer- and Internet-Based Psychotherapy Interventions. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2003;12(1):18–22.

Emmelkamp PM. Technological innovations in clinical assessment and psychotherapy. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74(6):336–43.

Barak A, Klein B, Proudfoot JG. Defining internet-supported therapeutic interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(1):4–17.

Hall P. Online psychosexual therapy: a summary of pilot study findings. Sex Relation Ther. 2004;19(2):167–78.

Cuijpers P, Marks IM, van Straten A, Cavanagh K, Gega L, Andersson G. Computer-aided psychotherapy for anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38(2):66–82.

Griffiths KM, Farrer L, Christensen H. The efficacy of internet interventions for depression and anxiety disorders: a review of randomised controlled trials. Med J Aust. 2010;192(11 Suppl):S4–11.

Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38(4):196–205.

Johansson R, Andersson G. Internet-based psychological treatments for depression. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(7):861–9. quiz 870.

Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, Gonder-Frederick LA, Magee JC, Bailey ET, Saylor DK, et al. Efficacy of an Internet-based behavioral intervention for adults with insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(7):692–8.

Dolemeyer R, Tietjen A, Kersting A, Wagner B. Internet-based interventions for eating disorders in adults: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:207.

Beintner I, Jacobi C, Taylor CB. Effects of an Internet-based prevention programme for eating disorders in the USA and Germany–a meta-analytic review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2012;20(1):1–8.

Knaevelsrud C, Maercker A. Internet-based treatment for PTSD reduces distress and facilitates the development of a strong therapeutic alliance: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:13.

van Diest SL, van Lankveld JJ, Leusink PM, Slob AK, Gijs L. Sex therapy through the internet for men with sexual dysfunctions: a pilot study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2007;33(2):115–33.

van Lankveld JJ, Leusink P, van Diest S, Gijs L, Slob AK. Internet-based brief sex therapy for heterosexual men with sexual dysfunctions: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Sex Med. 2009;6(8):2224–36.

Jones LM, McCabe MP. The effectiveness of an Internet-based psychological treatment program for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2011;8(10):2781–92.

McCabe MP, Price E, Piterman L, Lording D. Evaluation of an internet-based psychological intervention for the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20(3):324–30.

Schover L, Canada A, Yuan Y, Sui D, Neese L, Jenkins R, et al. A randomized trial of internet-based versus traditional sexual counseling for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment. Cancer. 2012;118(2):500–9.

Leusink PM, Aarts E. Treating erectile dysfunction through electronic consultation: a pilot study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2006;32(5):401–7.

Andersson E, Walen C, Hallberg J, Paxling B, Dahlin M, Almlov J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of guided Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2011;8(10):2800–9.

Schover LR, Yuan Y, Fellman BM, Odensky E, Lewis PE, Martinetti P. Efficacy trial of an Internet-based intervention for cancer-related female sexual dysfunction. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(11):1389–97.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: 4th, Text Revision edn; 2000.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 20:22–33. quiz 34-57.

Arrindell WA, Boelens W, Lambert H. On the psychometric properties of the Maudsley Marital Questionnaire (MMQ): Evaluation of self-ratings in distressed and ‘normal’ volunteer couples based on the dutch version. Pers Individ Differences. 1983;4(3):293–306.

Rosen R, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh I, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49(6):822–30.

Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208.

Schaefer MT, Olson DH. Assessing Intimacy: The Pair Inventory. J Marital Fam Ther. 1981;7(1):47–60.

Thirlaway K, Fallowfield L, Cuzick J. The Sexual Activity Questionnaire: a measure of women’s sexual functioning. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(1):81–90.

Atkins L, Fallowfield LJ. Fallowfield’s Sexual Activity Questionnaire in women with without and at risk of cancer. Menopause Int. 2007;13(3):103–9.

ter Kuile MM, Brauer M, Laan E. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) and the Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS): psychometric properties within a Dutch population. J Sex Marital Ther. 2006;32(4):289–304.

Derogatis L, Clayton A, Lewis-D’Agostino D, Wunderlich G, Fu Y. Validation of the female sexual distress scale-revised for assessing distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2008;5(2):357–64.

Sprangers MA, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, Franklin J, te Velde A, Muller M, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: first results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(10):2756–68.

Fallowfield LJ, Leaity SK, Howell A, Benson S, Cella D. Assessment of quality of life in women undergoing hormonal therapy for breast cancer: validation of an endocrine symptom subscale for the FACT-B. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;55(2):189–99.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77.

Ware J, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83.

Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, Essink-Bot ML, Fekkes M, Sanderman R, et al. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1055–68.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988.

Derogatis LR, Rosen R, Leiblum S, Burnett A, Heiman J. The Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS): initial validation of a standardized scale for assessment of sexually related personal distress in women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(4):317–30.

Acknowledgements

Psychologists/sexologists: Eva Broomans, Daniela Hahn, Hannah Lassche, Aukje Schade. Collaborator: Virenze Institute for Mental Health Care. Research assistants: Miranda Gerritsma, Marianne Kuenen. Coordination of pilot study: Heleen Hauer. Participating hospitals: Albert Schweitzer Hospital, Dordrecht; Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam; Flevo Hospital, Almere; Kennemer Gasthuis, Haarlem; Medical Center Alkmaar, Alkmaar; The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam; Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam; Sint Lucas Andreas Hospital, Amsterdam; Slotervaart Hospital, Amsterdam; Spaarne Hospital, Hoofddorp.

Funding

This trial is funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant number NKI 2012-5388), the Dutch Pink Ribbon Foundation (grant number 2012.WO21.C138) and The Netherlands Cancer Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

NA is the principal investigator and JvL, HO and DH are the co-principal investigators of this study. SH is the PhD candidate on the study, and created the first draft of this manuscript based on the study protocol. EB played a key role in the development of the online CBT program and is one of the primary sexologists of this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Hummel, S.B., van Lankveld, J.J., Oldenburg, H.S. et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for sexual dysfunctions in women treated for breast cancer: design of a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer 15, 321 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1320-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1320-z