Abstract

Background

Although new individual treatments continue to reshape the landscape of clinical care in patients with lung cancer, most of the progress has been mainly of benefit to patients with lung adenocarcinomas rather than squamous cell lung carcinoma (SQCLC). Our study aimed to determine whether the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene mutation is present in pure SQCLC. We further determined the mutation frequency and the clinical and pathological features of groups that are in high risk for EGFR mutation.

Methods

A total of 185 Chinese patient specimens diagnosed as SQCLC in the Shanghai Chest Hospital at the Shanghai Jiao Tong University were selected for this study. Hematoxylin-eosin stained slides for all cases were reviewed and evaluated by immunohistochemical analysis with the aim of selecting samples with pure SQCLC. After screening, 22 cases were eliminated and 163 pure SQCLC cases remained. Amplification Refractory Mutation System was used to detect the EGFR gene mutation status in the 163 SQCLC specimens.

Results

A total of 28 cases with EGFR mutation were detected among the 163 specimens. The EGFR mutation rate was 17.2% (28/163). Sex and smoking status were significantly associated with the status of EGFR gene mutation (P = 0.022 and P = 0.049, respectively). Age and degree of differentiation were not significantly correlated to EGFR mutation (P = 0.730 and P = 0.651, respectively).

Conclusions

EGFR mutations are present in pure SQCLC, which are more frequently detected in females and nonsmoker patients. Our results indicate the importance for all patients with SQCLC to have EGFR mutation status examined. These patients with activating EGFR mutation could accept tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Our understanding of the molecular mechanisms that underlie the development of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) has increased significantly during the last decade. Although new discoveries continue to reshape the landscape of clinical care, most of the progress has been mainly of benefit to patients with adenocarcinomas of the lung [1]. The 45th American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO2009) stated that epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) should be the treatment of choice for advanced NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations. A recent study showed that squamous cell lung cancer (SQCLC) accounts for 20–30% of NSCLC [2]. Among the major histological subtypes of NSCLC, the study of the molecular abnormalities in SQCLC has recently started to make minor progress [3]. However, there is still a lack of effective targeted therapy for SQCLC.

The current consensus in the medical community is that EGFR mutations are predominantly found in lung adenocarcinoma patients who are Asian, female, and non- or mild smokers [4]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) 2012 guidelines for NSCLC treatment stated that EGFR mutation analysis and ALK gene rearrangement detection should not be routinely recommended for SQCLC [5]. However, in 2011, Tseng et al. conducted a retrospective study, in which 92 patients with advanced SQCLC and unknown EGFR mutation status were treated with erlotinib. The results showed an overall response rate (ORR) of 17.4% and a disease control rate (DCR) of 27.2%. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were both longer in patients with disease control than in those with progressive disease (7.8 vs. 1.3 months and 20.7 vs. 2.7 months, respectively; P < 0.0001 for both). From the results of the study, researchers concluded that a significant proportion of SQCLC patients could benefit from erlotinib treatment, and thus evaluation of EGFR mutation status would be necessary [6]. However, the EGFR mutation rate in resected SQCLC specimens is 0–7.4% [7,8] and 1–15% in biopsied SQCLC specimens [9]. These rates are much lower than the 42.7% (33.5–56.8%) rate found in lung adenocarcinomas [10]. Adenocarcinoma compositions could alter the EGFR mutation status of SQCLC, so whether the relevant mutation in SQCLC samples is caused by the inclusion of adenocarcinoma compositions is controversial. Thus far, few studies have shown EGFR mutation in SQCLC, and patients with activating EGFR mutation responded to TKIs treatment [11].

Thus, the primary objective of this study was to enhance the diagnostic accuracy for SQCLC using hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses. The non-SQCLC component was excluded to determine the presence of EGFR gene mutation in pure SQCLC. The pathological and clinical features of patients with the EGFR gene mutation status are also summarized. The secondary objective of this study was to examine the response of patients, with pure SQCLC and an EGFR mutation, to TKIs treatment.

Methods

Study samples

Tumor specimens were obtained from 185 Chinese patients with SQCLC that were surgically resected in the Shanghai Chest Hospital at Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Shanghai, China) between June 2006 and June 2012. A total of 119 males and 66 females, with a median age of 62.4 years, were included in the study. The research has been approved by the Ethic Committee, Shanghai Chest Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, and the approval is added as in Additional file 1. All patients provided written informed consent, and one of patient’s informed consent is added as in Additional file 2.

Study methods

Sample selection

H&E stained specimen slides were read by two experienced pulmonary pathologists and the diagnoses were made according to the 2004 WHO classification system for lung carcinoma. Each pathologist classified the tumor specimens independently and unanimous agreement was obtained. Samples were obtained from four different regions of each tumor. To exclude mixed, non-SQCLC tumor compositions, the highest differentiated sections in the tumors were selected for IHC analysis and DNA extraction. The differentiation of SQCLC was categorized as follows: well differentiated, more than 50% of obvious keratin pearl or intercellular bridge observed in tumor tissues; moderately differentiated, 20–50% of keratin pearl or intercellular bridge observed in tumor tissues; and poorly differentiated, less than 20% of keratin pearl or intercellular bridge.

IHC analysis

TTF-1 (Clone 8G7G3/1, DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark), CK7 (Clone OV-TL 12/30, DakoCytomation), ΔNP63 (P40, Calbiochem, California, USA) and high molecular cytokeratin (Clone 34βE12, DakoCytomation) were used for examination of the pathological histology that had been identified through H&E staining to exclude mixed and inconspicuous, adenocarcinoma components. Tissue sections were deparaffinized using xylene and dehydrated in alcohol. Antigen-retrieval was performed by heating the slides in 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 6.0) for 10 min. Tissue slides were incubated in 0.3% H2O2 for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Sections were incubated with primary antibody for 30 min at room temperature. Sections incubated with antibody diluents (Immunologic, Duiven, Netherlands) were used as the negative control. Sections were developed using the Dako EnVision™ visualization system (DakoCytomation). Pretreatment conditions and antibody dilutions are available upon request.

DNA extraction and mutation test

The pure squamous cell cancers were determined by IHC analysis results. ∆NP63 and 34βE12 were positive, and TTF-1 and CK7 were negative. The area of residual, alveolar epithelium was avoided when acquiring the sample tissues (Figure 1) to ensure that the EGFR gene mutation was present in pure SQCLC. DNA was extracted from five serial slices of a 5-μm paraffin section using the DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The highly sensitive method Amplification Refractory Mutation System (ARMS) (ADx-EG01, Xiamen, China) was used to detect the EGFR gene mutation status [12,13].

Method for obtaining pure SQCLC tissues for detection ofEGFRgene mutation. [A] HE stained slice diagnosed as SQCLC. [B] TTF-1 staining of the residual alveolar epithelium. When obtaining the SQCLC tissues for mutation analysis, the positive regions (indicated by green borders) were avoided. [C] ∆NP63 staining. The region outlined by the green border was used to detect the EGFR gene mutation status.

Statistical methods

Univariate analysis was conducted on sex, age, smoking status and the degree of differentiation using Fisher’s exact test to evaluate the effects of clinical and pathological factors relating to the patients and disease characteristics. All statistical tests were done using SPSS17.0 software (http://www.spss.com, IBM Corp., Chicago, IL). Two-tailed t-tests were used and P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

H&E staining and IHC analysis

A total of 185 surgical SQCLC samples were examined. Ten samples were excluded after H&E staining owing to the SQCLC sample containing less than a 10% portion of mixed adenocarcinoma, or lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma, or basal-like large cell carcinoma that had been diagnosed as SQCLC. An additional 12 samples were excluded owing to IHC results. In some cases, all results were negative after analysis using the primary antibodies ΔNP63 (P40), TTF-1, CK7 and 34βE12, and the cases should be diagnosed as large cell carcinoma. In other cases, the results of ΔNP63 (P40) and 34βE12 were negative but positive for TTF-1 and CK7, and the cases should be diagnosed as poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure 2). The remaining 163 cases were enrolled in the study to evaluate the EGFR gene mutation status in pure SQCLC.

A total of 114 (69.9%) males and 49 (30.1%) females with a median age of 61.3 years (range 33–81 years) were enrolled. Cases were divided into three groups based on age, and included 11 cases 30–49 years of age, 123 cases 50–69 years of age and 29 cases ≥70 years of age. In total, 59 cases were considered as well differentiated, 56 moderately differentiated and 48 poorly differentiated. A total of 78 patients were non-smokers, 61 patients were smokers and in 24 cases, smoking status was unknown.

EGFR gene mutation analysis

An EGFR gene mutation was detected in 28 of the 163 samples, giving a mutation rate of 17.2% (Table 1). There were 16 cases with 19del mutation and 11 cases with 21L858R mutation, and one 64 years old female smoking patient with poorly differentiation SQCLC harbored both 19del and 21L858R mutations. Sex and smoking status were significantly associated with the rate of EGFR gene mutation (P = 0.022 and P = 0.049, respectively). Age and degree of differentiation were not significantly correlated to EGFR gene mutation (P = 0.730 and P = 0.651, respectively).

Discussion

EGFR-TKIs have been proven to be effective for treating NSCLC cases with EGFR mutations. Therefore, many studies have focused on patients with the presence of active EGFR mutations, especially those with adenocarcinoma histology. Thus far, studies involving EGFR gene mutations and the response to TKIs treatment in SQCLC patients with these mutations have been very few [11] and there has been little consensus in the results. In 2014, Kim et al. reported that an EGFR mutation rate of 6% in SQCLC patients [3]. In 2011, researchers from the Netherlands carried out a multicenter study and found no EGFR gene mutation in SQCLC patients [7]. In 2010, Japanese researchers found that the rate of EGFR gene mutation in resected SQCLC specimens was 7.4% [8]. In 2007, researchers in Korea found a response to TKI treatment in 69 patients with advanced SQCLC and an EGFR mutation rate up to 15% (3/20) [9]. In addition, their results indicated that EGFR gene mutation could be the predictive factor for the response to TKIs, although the efficacy was lower for SQCLC than for adenocarcinoma. In the current study, IHC analysis was used to select only pure SQCLC to help elucidate whether the EGFR gene is mutated in SQCLC and, if so, to determine the mutation rate, as well as the clinical and pathological features in high risk groups. In 2010, William Travis pointed out that there are some limitations on samples obtained via bronchoscopy or transthoracic needle biopsy when making diagnoses based on pathology and when detecting genomic alterations, owing to the high degree of heterogeneity in lung cancers [14]. Thus, only surgical SQCLC specimens were included in the current study. In addition, primary antibody P40 was used instead of P63, due to its higher specificity when confirming squamous cell cancers [15,16].

In our study, we found a total rate of 17.2% for the EGFR gene mutation in patients with SQCLC. This rate was higher than that found in our previous analyses (0–15%) [3,7-9]. There could be several possible explanations for the different results. One possibility could reflect the different sensitivities among the different methods used for analyses. Most of the former studies detected the EGFR gene mutation by direct DNA sequencing, which has a sensitivity of only 70%, much lower than the 99% sensitivity of ARMS [12,13]. Thus, the different detection assay could interfere with the mutation relevance rate. A second explanation may be owing to the difference in the sex ratio of the enrolled patients. Because the incidence of SQCLC is lower in females, as also evident in the current study, fewer females were included. The current study showed that the rate of EGFR gene mutation in females with SQCLC was 28.6%, which is significantly higher than in males (12.3%) (P = 0.022). As a result, we speculate that the total rate of mutation in SQCLC might increase as the number of female cases increases. A third explanation may involve differences among races and regions, as the factors that drive genomic alteration between races are consequential [17,18]. For example, the K-ras gene mutation is higher in Caucasian NSCLC patients than in Asian NSCLC patients. Similarly, Asian patients with adenocarcinoma also have a higher incidence of the EGFR gene mutation than Caucasian patients. Furthermore, all of our samples are Chinese patients, which may lead to a different result from other Asian or Caucasian patients.

We found that sex and smoking status were significant factors in the EGFR gene mutation rate in SQCLC (female: 28.6% and male: 12.3%, P = 0.022; non-smoking: 26.2%, moking: 11.5% and unknown smoking status: 20.8%, P = 0.049). However, age and the degree of differentiation had no affect on the mutation rate. To our knowledge, a similar conclusion has not been reported thus far. If further research finds it to be similar to the EGFR gene mutation found in adenocarcinoma among high-risk groups, oncologists should consider testing female and non/mild smoking SQCLC patients for EGFR gene mutation status and begin TKIs treatment if appropriate.

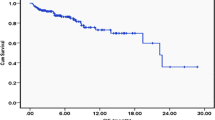

In 2011, Shukuya et al. [19] carried out a pooled analysis of published reports regarding the efficacy of gefitinib for use in non-adenocarcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer patients harboring EGFR mutations. The analysis showed that gefitinib is less effective in non-adenocarcinoma NSCLC harboring EGFR mutations than in adenocarcinoma harboring EGFR mutations (response rate (RR): 27% vs. 66%, P = 0.000028; DCR: 67–70% vs. 92–93%, P = 0.000014; median progression-free survival (mPFS): 3.0 vs. 9.4 months, P = 0.0001). We could not obtain adequate data regarding the response to TKIs treatment due to the limited number of EGFR gene mutant SQCLC patients taking TKIs. Follow-up was done on 13 of the 28 EGFR gene mutant cases in our study. Of these, four subjects had died and four subjects were in advanced stages of disease and accepted TKIs treatment. All four acquired clinical benefits from this treatment. Other driving genomic alterations, such as in ALK and c-MET genes, have also been gaining recent attention. However, their mutation rates are lower (ALK: 1.5–6.7% [20-22], and c-MET: 2–4.1% [23,24]). Thus, it is of utmost importance that SQCLC patients have EGFR gene mutation examined and accept the TKIs treatment if appropriate.

Conclusion

EGFR mutations are present in pure SQCLC, and are more frequently detected in females and nonsmoker patients. It is important for all patients with SQCLC to have EGFR mutation status examined. These patients with activating EGFR mutation could accept TKIs treatment.

Abbreviations

- SQCLC:

-

Squamous cell lung carcinoma

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin-eosin

- TKIs:

-

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small-cell lung carcinoma

- ORR:

-

Overall response rate

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- DCR:

-

Disease control rate

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemical

- RR:

-

Response rate

- mPFS:

-

Median progression-free survival

References

Kris MG, Johnson BE, Kwiatkowski DJ, Berry LD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Iafrate AJ. Identification of driver mutations in tumor specimens from 1,000 patients with lung adenocarcinoma: the NCI’s Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium (LCMC). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2011;29:abstr CRA7506.

Travis WD. Pathology of lung cancer. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32:669–92.

Hirotsugu K, Masakuni S, Yasuhiro K, Isaka M, Takahashi T, Taira T, et al. Prospective genetic profiling of squamous cell lung cancer and adenosquamous carcinoma in Japanese patients by multitarget assays. Kenmotsu et al. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:786.

Ahn MJ, Park BB, Ahn JS, Kim SW, Kim HT, Lee JS, et al. Are there any ethnic differences in molecular predictors of erlotinib efficacy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer? Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(12):3860–6.

Ettinger DS, Akerley W, Borghaei H, Chang AC, Cheney RT, Chirieac LR, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10(10):1236–71.

Jeng-Sen T, Tsung-Ying Y. Retrospective study of erlotinib in patients with advanced squamous lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012;77:128–33.

Thunnissen E, Boers E, Heideman DA, Grünberg K, Kuik DJ, Noorduin A, et al. Correlation of immunohistochemical staining p63 and TTF-1 with EGFR and K-ras mutational spectrum and diagnostic reproducibility in non small cell lung carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2012;461(6):629–38. doi: 10.1007/s00428-012-1324-x.

Miyamae Y1, Shimizu K, Hirato J, Araki T, Tanaka K, Ogawa H, et al. Significance of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in squamous cell lung carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:921–8.

Rekhtman N, Paik PK, Arcila ME, Tafe LJ, Oxnard GR, Moreira AL, et al. Clarifying the spectrum of driver oncogene mutations in biomarker-verified squamous carcinoma of lung: lack of EGFR/KRAS and presence of PIK3CA/AKT1 mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1167–76.

Qing Z, Jie Z. Mutation-specific antibodies for the detection of EGFR mutations in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Chin J Pathol. 2013;3:168–72.

Wheler JJ, Tsimberidou AM, Falchook GS, Zinner RG, Hong DS, Fok JY, et al. Combining erlotinib and cetuximab is associated with activity in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (including squamous cell carcinomas) and wild-type EGFR or resistant mutations. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12(10):2167–75.

Yi L, Bing L, Xiao-Yan L, Li JJ, Qin HF, Tang CH, et al. A comparison of ARMS and direct sequencing for EGFR mutation analysis and Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors treatment prediction in body fluid samples of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011;30:111.

Qing Z, Xu-Chao Z, Yi-Long W, Yin XL, Yang JJ, Xu CR, et al. Relative abundance of EGFR mutations predicts Benet from getinib treatment for advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3316–21.

Travis WD, Rekhtman N. Pathological diagnosis and classifi cation of lung cancer in small biopsies and cytology: strategic management of tissue for molecular testing. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32:22–31.

Rekhtman N, Ang DC, Sima CS, Travis WD, Moreira AL. Immunohistochemical algorithm for diff erentiation of lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma based on large series of whole-tissue sections with validation in small specimens. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1348–59.

Bishop JA, Teruya-Feldstein J, Westra WH, Pelosi G, Travis WD, Rekhtman N. p40 (DeltaNp63) is superior to p63 for the diagnosis of pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:405–15.

Tsao AS, Tang XM, Sabloff B, Xiao L, Shigematsu H, Roth J, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of the EGFR gene mutation in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1(3):231–9.

Bell DW, Brannigan BW, Ket M, Finkelstein DM, Sordella R, Settleman J, et al. Increased prevalence of EGFR-mutant lung cancer in women and in East Asian populations: analysis of estrogen-related polymorphisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(13):4079–84.

Shukuya T, Takahashi T, Kaira R, Ono A, Nakamura Y, Tsuya A, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib for non-adenocarcinoma non-small-cell lung cancer patients harboring epidermal growth factor receptor mutations: a pooled analysis of published reports. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(5):1032–7.

Paik JH, Choi CM, Kim H, Jang SJ, Choe G, Kim DK, et al. Clinicopathologic implication of ALK rearrangement in surgically resected lung cancer A proposal of diagnostic algorithm for ALK-rearranged adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2012;76:403–9.

Martelli MP, Sozzi G, Hernandez L, Pettirossi V, Navarro A, Conte D, et al. EML4-ALK rearrangement in non-small cell lung cancer and nontumor lung tissues. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:661–70.

Wong DW, Leung EL, So KK, Tam IY, Sihoe AD, Cheng LC, et al. The EML4-ALK fusion gene is involved in various histologic types of lung cancers from nonsmokers with wild-type EGFR and KRAS. Cancer. 2009;115:1723–33.

Ma PC, Jagadeeswaran R, Jagadeesh S, Tretiakova MS, Nallasura V, Fox EA, et al. Functional expression and mutations of c-Met and its therapeutic inhibition with SU11274 and small interfering RNA in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(4):1479–88.

Janku F, Garrido-Laguna I, Petruzelka LB, Stewart DJ, Kurzrock R. Novel therapeutic targets in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(9):1601–12.

Acknowledgements

We thank Han, B. Ph.D. who revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and Zhao, R. M.D. who helped us acquire the data. Also we thank Wu, J. M.D. who helped us draft the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JZ made substantial contributions to conception, design trials, analysis and interpretation of data. QZ carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in the sequence alignment, acquired data, and drafted the manuscript. LZ has given final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Approval of the ethic committee.

Additional file 2:

The informed consent of patients.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Q., Zhu, L. & Zhang, J. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation status in pure squamous-cell lung cancer in Chinese patients. BMC Cancer 15, 88 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1056-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1056-9